Animal

- For other uses of the word "animal", see animal (disambiguation).

| Animals | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Sea nettles, Chrysaora quinquecirrha | ||||

| Scientific classification | ||||

| ||||

| Phyla | ||||

|

Animals are a major group of organisms, classified as the kingdom Animalia or Metazoa. In general they are multicellular, capable of locomotion and responsive to their environment, and feed by consuming other organisms. Their body plan becomes fixed as they develop, usually early on in their development as embryos, although some undergo a process of metamorphosis later on.

For a long time, living organisms were divided into the animal kingdom (Animalia) and the plant kingdom (Plantae). These were distinguished based on such characteristics as whether the organisms moved, had body parts, and took nurishment from the outside (animals), or were stationary and was able to produce its own food by photosynthesis. However, there remained main organisms that were difficult to classify as plant or animal, and which seemed to belong to both, or neither, kingdom. Subsequently, more kingdoms were recognized, such as the five kingdom system of Protista, Monera, Fungi, Plantae, and Animalia, or a system that places three domains above the kingdoms: Archaea, Eubacteria, and Eukaryota. (See taxonomy.) Kingdom Animalia has several characteristics that set it apart from other living things. Animals are eukaryotic and multicellular, which separates them from bacteria and most protists. They are heterotrophic, generally digesting food in an internal chamber, which separates them from plants and algae. They are also distinguished from plants, algae, and fungi by lacking cell walls.

In everyday usage animal refers to any member of the animal kingdom that is not a human being, and sometimes excludes insects (although including such arthropods as crabs). The separate of the term from its use with humans is a natural result of the unique role of humans, that exhibit characteristics of *** spirituality. Many religions also consider humans to have a soul or spirit, that allows their life beyond death.

This common use of the term may stem from the familiarity with zoo animals, farm animals and pets.

The name animal comes from the Latin word animal, of which animalia is the plural, and ultimately from anima, meaning vital breath or soul.

Classification

Within a kingdom, animals are further separated into phyla, which is a major group. ??? Need to explain. These are further divided into classes, orders, families, gnera, and species.

superphyla superregnum

Animals can be further divided into two major groups, the vertebrates that ????, and the invertebrates that ????. There are about 40,000 species of vertebrates and more than 1 million known species of invertebrates, but it is generally established that only a small percentage of all invertebrate species are known. Approximately 1.8 million species of animals and plants have been identified (excluding the diverse kingdoms of fungi, bacteria, and other unicellular organisms), but some biologists estimate there may be more than 150 million species of living things on the earth. Indeed, Ed Wilson in his 1992 book The Diversity of Life, stated "How many species of organisms are there on earth? We don't know, not even to the nearest order of magnitude. The numbers could be as close to 10 million or as high as 100 million."

Of those that have been identified, more than half are insects (about 57%), and nearly half of all insect species are beetles, meaning that beetles, with over 400,000 identified species, represent about 25% of all named species in the plant and animal kingdoms. This fact led to the famous quip from J. B. S. Haldane, perhaps apocryphal, who when asked what one could conclude as to the nature of the Creator from a study of his creation, replied: "An inordinate fondness for beetles."

There are also approximately 9,000 named species of birds, 27,000 known species of fish, and a ledger of about 4,000 or so mammalian species. These groups have been diligently catalogued, unlike insects which rank among the most uncounted groups of organisms.

Structure

bilaterial and radial symmetry

With a few exceptions, most notably the sponges (Phylum Porifera), animals have bodies differentiated into separate tissues. These include muscles, which are able to contract and control locomotion, and a nervous system, which sends and processes signals. There is also typically an internal digestive chamber, with one or two openings. Animals with this sort of organization are called metazoans, or eumetazoans when the former is used for animals in general.

All animals have eukaryotic cells, surrounded by a characteristic extracellular matrix composed of collagen and elastic glycoproteins. This may be calcified to form structures like shells, bones, and spicules. During development it forms a relatively flexible framework upon which cells can move about and be reorganized, making complex structures possible. In contrast, other multicellular organisms like plants and fungi have cells held in place by cell walls, and so develop by progressive growth. Also, unique to animal cells are the following intercellular junctions: tight junctions, gap junctions, and desmosomes.

Reproduction and development

Nearly all animals undergo some form of sexual reproduction. Adults are diploid or occasionally polyploid. They have a few specialized reproductive cells, which undergo meiosis to produce smaller motile spermatozoa or larger non-motile ova. These fuse to form zygotes, which develop into new individuals.

Many animals are also capable of asexual reproduction. This may take place through parthenogenesis, where fertile eggs are produced without mating, or in some cases through fragmentation.

A zygote initially develops into a hollow sphere, called a blastula, which undergoes rearrangement and differentiation. In sponges, blastula larvae swim to a new location and develop into a new sponge. In most other groups, the blastula undergoes more complicated rearrangement. It first invaginates to form a gastrula with a digestive chamber, and two separate germ layers - an external ectoderm and an internal endoderm. In most cases, a mesoderm also develops between them. These germ layers then differentiate to form tissues and organs.

Animals grow by indirectly using the energy of sunlight. Plants use this energy to turn air into simple sugars using a process known as photosynthesis. These sugars are then used as the building blocks which allow the plant to grow. When animals eat these plants (or eat other animals which have eaten plants), the sugars produced by the plant are used by the animal. They are either used directly to help the animal grow, or broken down, releasing stored solar energy, and giving the animal the energy required for motion. This process is known as glycolysis.

Origin and fossil record

Animals are generally considered to have evolved from flagellate protozoa. Their closest living relatives are the choanoflagellates, collared flagellates that have the same structure as certain sponge cells do. Molecular studies place them in a supergroup called the opisthokonts, which also include the fungi and a few small parasitic protists. The name comes from the posterior location of the flagellum in motile cells, such as most animal sperm, whereas other eukaryotes tend to have anterior flagella.

The first fossils that might represent animals appear towards the end of the Precambrian, around 600 million years ago, and are known as the Vendian biota. These are difficult to relate to later fossils, however. Some may represent precursors of modern phyla, but they may be separate groups, and it is possible they are not really animals at all. Aside from them, most animal phyla with known phyla make a more or less simultaneous appearance during the Cambrian period, about 570 million years ago. It is still disputed whether this event, called the Cambrian explosion, represents a rapid divergence between different groups or a change in conditions that made fossilization possible.

Groups of animals

The sponges (Porifera) diverged from other animals early. As mentioned, they lack the complex organization found in most other phyla. Their cells are differentiated, but not organized into distinct tissues. Sponges are sessile and typically feed by drawing in water through pores all Archaeocyatha]], which have fused skeletons, may represent sponges or a separate phylum.

Among the eumetazoan phyla, two are radially symmetric and have digestive chambers with a single opening, which serves as both the mouth and the anus. These are the Cnidaria, which include sea anemones, corals, and jellyfish, and the Ctenophora or comb jellies. Both have distinct tissues, but they are not organized into organs. There are only two main germ layers, the ectoderm and endoderm, with only scattered cells between them. As such, these animals are sometimes called diploblastic. The tiny phylum Placozoa is similar, but individuals do not have a permanent digestive chamber.

The remaining animals form a monophyletic group called the Bilateria. For the most part, they are bilaterally symmetric, and often have a specialized head with feeding and sensory organs. The body is triploblastic, i.e. all three germ layers are well-developed, and tissues form distinct organs. The digestive chamber has two openings, a mouth and an anus, and there is also an internal body cavity called a coelom or pseudocoelom. There are exceptions to each of these characteristics, however - for instance adult echinoderms are radially symmetric, and certain parasitic worms have extremely simplified body structures.

Genetic studies have considerably changed our understanding of the relationships within the Bilateria. Most appear to belong to four major lineages:

- Deuterostomes

- Ecdysozoa

- Platyzoa

- Lophotrochozoa

In addition to these, there are a few small groups of bilaterians with relatively similar structure that appear to have diverged before these major groups. These include the Acoelomorpha, Rhombozoa, and Orthonectida. The Myxozoa, single-celled parasites that were originally considered Protozoa, are now believed to have developed from the Bilateria as well.

Deuterostomes

Deuterostomes differ from the other Bilateria, called protostomes, in several ways. In both cases there is a complete digestive tract. However, in protostomes the initial opening (the archenteron) develops into the mouth, and an anus forms separately. In deuterostomes this is reversed. In most protostomes cells simply fill in the interior of the gastrula to form the mesoderm, called schizocoelous development, but in deuterostomes it forms through invagination of the endoderm, called enterocoelic pouching. Deuterostomes also have a dorsal, rather than a ventral, nerve chord and their embryos undergo different cleavage.

All this suggests the deuterostomes and protostomes are separate, monophyletic lineages. The main phyla of deuterostomes are the Echinodermata and Chordata. The former are radially symmetric and exclusively marine, such as sea stars, sea urchins, and sea cucumbers. The latter are dominated by the vertebrates, animals with backbones. These include fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals.

In addition to these, the deuterostomes also include the Hemichordata or acorn worms. Although they are not especially prominent today, the important fossil graptolites may belong to this group. The Chaetognatha or arrow worms may also be deuterostomes, but this is less certain.

Ecdysozoa

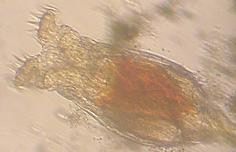

The Ecdysozoa are protostomes, named after the common trait of growth by moulting or ecdysis. The largest animal phylum belongs here, the Arthropoda, including insects, spiders, crabs, and their kin. All these organisms have a body divided into repeating segments, typically with paired appendages. Two smaller phyla, the Onychophora and Tardigrada, are close relatives of the arthropods and share these traits.

The ecdysozoans also include the Nematoda or roundworms, the second largest animal phylum. Roundworms are typically microscopic, and occur in nearly every environment where there is water. A number are important parasites. Smaller phyla related to them are the Nematomorpha or horsehair worms, which are visible to the unaided eye, and the Kinorhyncha, Priapulida, and Loricifera, which are all microscopic. These groups have a reduced coelom, called a pseudocoelom.

The remaining two groups of protostomes are sometimes grouped together as the Spiralia, since in both embryos develop with spiral cleavage.

Platyzoa

The Platyzoa include the phylum Platyhelminthes, the flatworms. These were originally considered some of the most primitive Bilateria, but it now appears they developed from more complex ancestors.

A number of parasites are included in this group, such as the flukes and tapeworms. Flatworms lack a coelom, as do their closest relatives, the microscopic Gastrotricha.

The other platyzoan phyla are microscopic and pseudocoelomate. The most prominent are the Rotifera or rotifers, which are common in aqueous environments. They also include the Acanthocephala or spiny-headed worms, the Gnathostomulida, Micrognathozoa, and possibly the Cycliophora. These groups share the presence of complex jaws, from which they are called the Gnathifera.

Lophotrochozoa

The Lophotrochozoa include two of the most successful animal phyla, the Mollusca and Annelida. The former includes animals such as snails, clams, and squids, and the latter comprises the segmented worms, such as earthworms and leeches. These two groups have long been considered close relatives because of the common presence of trochophore larvae, but the annelids were considered closer to the arthropods, because they are both segmented. Now this is generally considered convergent evolution, owing to many morphological and genetic differences between the two phyla.

The Lophotrochozoa also include the Nemertea or ribbon worms, the Sipuncula, and several phyla that have a fan of cilia around the mouth, called a lophophore. These were traditionally grouped together as the lophophorates, but it now appears they are paraphyletic, some closer to the Nemertea and some to the Mollusca and Annelida. They include the Brachiopoda or lamp shells, which are prominent in the fossil record, the Entoprocta, the Phoronida, and possibly the Bryozoa or moss animals.

History of classification

Aristotle divided the living world between animals and plants, and this was followed by Carolus Linnaeus in the first hierarchical classification. Since then biologists have begun emphasizing evolutionary relationships, and so these groups have been restricted somewhat. For instance, microscopic protozoa were originally considered animals because they move, but are now treated separately.

In Linnaeus' original scheme, the animals were one of three kingdoms, divided into the classes of Vermes, Insecta, Pisces, Amphibia, Aves, and Mammalia. Since then the last four have all been subsumed into a single phylum, the Chordata, whereas the various other forms have been separated out. The above lists represent our current understanding of the group, though there is some variation from source to source.

Examples

Some well-known types of animals, listed by their common names:

|

|

|

|

|

Reference

- Klaus Nielsen. Animal Evolution: Interrelationships of the Living Phyla (2nd edition). Oxford Univ. Press, 2001.

- Knut Schmidt-Nielsen. Animal Physiology: Adaptation and Environment. (5th edition). Cambridge Univ. Press, 1997.

External links

- Cane lupo di Saarloos

- Animals Search Engine

- wikianimals.com - Documenting the animal kingdom

- Tree of Life

- A Multimedia Database of Various UK or Endangered Species

- Animals and Birds Names - Large table of words: animal, collective, male, female, young, & home

- English Animal Adjectives

- Sounds of the World's Animals - animal sounds in many languages

- FindSounds - Search the Web for Sounds - sound files including animal sound files

- Australian Animals

- AnimalReviews - animals reviewed and evaluated

- The animal photo archive - Photos of animals

- Photo gallery of animals pictures from the entire world.

- Birds Name Check List in Latin, English, Russian and Hebrew.

- Animals - Wiki Fauna

- Wild Animals Online - an online encyclopedia of wild animals - facts, photos

- The Phyla of the Animals

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.