Jackal

| Jackal | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

A black-backed jackal in Masaai Mara

| ||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

|

Golden jackal, Canis aureus |

Jackal is the common name for Old World, coyote-like mammals in any of three species in the genus Canis of the family Canidae: Canis aureus (golden jackal), Canis adustus (side-striped jackal), and Canis mesomelas (black-backed jackal). These small to medium-sized canids, with long legs and curved canine teeth, are found in Africa, Asia, and southeastern Europe. The name jackal sometimes also is applied to a fourth canid species, Canis simensis, which may be known as the Simien jackal, Abyssinian wolf, red fox, or Ethiopian wolf. However, this species generally is considered closer to the wolf (also a member of the Canis genus) and is not considered in this article.

All species of jackal are capable predators. (All three hunt rodents and small mammals regularly, with the golden and black-backed species known to hunt poisonous snakes, large ground birds such as bustards, and mammals as large as young antelope. Some also take some vegetative matter, such as berries.) However, their popular image as scavengers has resulted in a negative public image.

Overview and description

The genus to which jackals belong, Canis, contains about 7 to 10 extant species and many extinct species, including wolves, dogs, coyotes, and dingoes. The jackal generally is applied to members of any of three (sometimes four) small to medium-sized species of the family Canidae, found in Africa, Asia and southeastern Europe (Ivory 1999).

Jackals fill a similar ecological niche to the coyote in North America, that of predators of small to medium-sized animals, scavengers, and omnivores. Their long legs and curved canine teeth are adapted for hunting small mammals, birds, and reptiles. Big feet and fused leg bones give them a long-distance runner's physique, capable of maintaining speeds of 16 kilometers/hour (10 miles per hour) (just over 6 minutes/mile) for extended periods of time. They are nocturnal, most active at dawn and dusk.

In jackal society, the social unit is that of a monogamous pair that defends its territory from other pairs. These territories are defended by vigorously chasing intruding rivals and marking landmarks around the territory with urine and feces. The territory may be large enough to hold some young adults who stay with their parents until they establish their own territory.

Jackals may occasionally assemble in small packs, for example to scavenge a carcass, but normally hunt alone or as a pair.

Golden jackal

The golden jackal (Canis aureus), also called the Asiatic, oriental, or common jackal, is native to north and east Africa, southeastern Europe, and South Asia to Burma. It is the largest of the jackals, and the only species to occur outside Africa, with 13 different subspecies being recognized (Wozencraft 2005).

The golden jackal's short, coarse fur is usually yellow to pale gold and brown-tipped, though the color can vary with season and region. On the Serengeti Plain in Northern Tanzania for example, the golden jackal's fur is brown-grizzled yellow in the wet season (December-January), changing to pale gold in the dry season (September-October) (Ivory 1999). Jackals living in mountainous regions may have a grayer shade of fur (Jhala and Moehiman 2005).

The golden jackal is generally 70 to 105 centimeters (28–42 inches) in length, with a tail length of about 25 centimeters (10 inches). Its standing height is approximately 38 to 50 centimeters (16–20 inches) at the shoulder. Average weight is 7 to 15 kilograms (15–33 pounds), with males tending to be 15 percent heavier than the females (Ivory 1999). Scent glands are present on the face and the anus and genital regions. Females have 4-8 mammae. The dental formula is I 3/3 C 1/1 Pm 4/4 M 2/3 = 42 (Jhala and Moehiman 2005).

In all their ranges, the golden jackal displays a great deal of diversity in appearance. Jackals living in north Africa tend to be larger and have longer carnassials than those living in the Middle East (Macdonald 1992). Moroccan golden jackals are paler and have more pointed snouts than Egyptian golden jackals (Hutchinson 1923).

The golden jackal generally is grouped with the other jackals (the black-backed jackal and the side-striped jackal), although genetic research suggests that the golden jackal is more closely related to a "wolf" group that also includes the gray wolf (and the domestic dog) and the coyote (Lindblad-Toh et al. 2005).

Results from recent studies of mDNA from golden jackals indicate that the specimens from Africa are genetically closer to the gray wolf than are the specimens from Eurasia (Koepfli et. al. 2015). The genetic evidence is consistent with the form of the skull, which also bears more similarities to those of the coyote and the gray wolf than to those of the other jackal species. As a result it has been suggested that the six C. aureus subspecies found in Africa should be reclassified under the new species C. anthus (African golden wolf), reducing the number of golden jackal subspecies to seven.

Side-striped jackal

The side-striped jackal (Canis adustus) is native to central and southern Africa (Wozencraft 2005). it is a grayish brown to tan with a white stripe from the front legs to the hips and has a dark tail that has a white tip. The side-striped Jackal can weigh from 6.2 to 13.6 kilograms (14 to 30 pounds), with males tending to be larger than the females. It is social within small family groups, communicating via yips, "screams," and a soft owl like hooting call. It is nocturnal, and rarely active during the day.

The side-striped jackal lives in the damp woodland areas along with grassland, bush, and marshes. It eats fruit, insects, and small mammals such as rats, hares, and birds. It will go for the young of larger animals such as warthogs and gazelles. It also will often follow big cats to scavenge their kills, but has never been observed taking down larger prey on its own.

The breeding season for this species depends on where they live; in southern Africa breeding starts in June and ends in November. The side-striped Jackal has a gestation period of 57 to 70 days with average litter of 3 to 6 young. The young reach sexual maturity at 6 to 8 months old and typically begin to leave when 11 months old. The side-striped jackal mates for life, forming monogamous pairs.

Black-backed jackal

The black-backed jackal (Canis mesomelas), also known as the silver-backed jackal, inhabits two areas of the African continent separated by roughly 900 kilometers. One region includes the southern-most tip of the continent including South Africa, Namibia, Botswana, and Zimbabwe. The other area is along the eastern coastline, including Kenya, Somalia, and Ethiopia (Fishman 2000).

As its name suggests, the species' most distinguishing feature is the silver-black fur running from the back of the neck to the base of the tail. The chest and under parts are white to rusty-white, whereas the rest of the body ranges from reddish brown to ginger. Females tend not to be as richly colored as males, like many other animals, such as ducks. The winter coat of adult males develops a reddish to an almost deep russet red color (Fishman 2000).

The black-backed jackal is typically 32 to 42 centimeters (14 to 19 inches) high at the shoulder, 45-90 centimeters (18-36 inches) long, and 15 to 30 pounds (7–13.5 kilograms) in weight). Specimens in the southern part of the continent tend to be larger than their more northern cousins (Fishman 2000).

The black-backed jackal is noticeably more slender than other species of jackals, with large, erect, pointed ears. The muzzle is long and pointed. The dental formula is 3/3-1/1-4/4-2/3=42 (Loveridge and Nel 2005). Scent glands are present on the face and the anus and genital regions. The Black-backed Jackal has 6-8 mammae.

The black-backed jackal usually lives together in pairs that last for life, but often hunts in packs to catch larger prey such as the Impala and antelopes. It is very territorial; each pair dominates a permanent territory. It is mainly nocturnal, but the black-backed Jackal comes out in the day occasionally.

These jackals adapt their diets to the available food sources in their habitat. It often scavenges, but it is also a successful hunter. Its omnivorous diet includes, among other things the Impala, fur seal cubs, gazelles, guineafowls, insects, rodents, hares, lizards, snakes, fruits and berries, domestic animals such as sheep and goats, and carrion. As with most other species of small canids, jackals typically forage alone or in pairs. When foraging, the black-backed Jackal moves with a distinctive trotting gait.

Its predators include the leopard and humans. Jackals are sometimes killed for their furs, or because they are considered predators of livestock.

Cultural perceptions

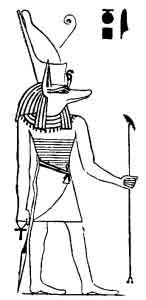

The Egyptian god of embalming, Anubis, was portrayed as a jackal-headed man, or as a jackal wearing ribbons and holding a flagellum, a symbol of protection, in the crook of its arm. Anubis was always shown as a black jackal or dog, even though real jackals are typically tan or a light brown. To the Egyptians, black was the color of regeneration, death, and the night. It was also the color that the body turned during mummification. The reason for Anubis' animal model being canine is based on what the ancient Egyptians themselves observed of the creature—dogs and jackals often haunted the edges of the desert, especially near the cemeteries where the dead were buried. In fact, it is thought that the Egyptians began the practice of making elaborate graves and tombs to protect the dead from desecration by jackals.

The Greeks god Hermes and the monster Cerberus are thought to derive their origins from the golden jackal (Jhala and Moehiman 2005).

The jackal is mentioned frequently in the Bible, where it is portrayed as a sinister creature, most notably in Psalm 63:9-11, where it is stated that non-believers would become food for the jackals. In his book Running with the Fox, David W. Macdonald theorizes that due to the general scarcity and elusiveness of foxes in Israel, the author of the Book of Judges may have actually been describing the much more common golden jackals when narrating how Samson tied torches to the tails of 300 foxes to make them destroy the vineyards of the Philistines.

The expression "jackalling" is sometimes used to describe the work done by a subordinate in order to save the time of a superior. (For example, a junior lawyer may peruse large quantities of material on behalf of a barrister.) This came from the tradition that the jackal will sometimes lead a lion to its prey. In other languages, the same word is sometimes used to describe the behavior of persons who try to scavenge scraps from the misfortunes of others; for example, by looting a village from which its inhabitants have fled because of a disaster.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Alderton, D. 2004. Foxes, Wolves, and Wild Dogs of the World. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 081605715X.

- Fishman, B. 2000. Canis mesomelas. Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved March 4, 2019.

- Hutchinson's Animals of All Countries: The Living Animals of the World in Picture and Story. 1923. London: Hutchinson.

- Ivory, A. 1999. Canis aureus. Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved March 4, 2019.

- Jhala, Y. V., and P. D. Moehiman. 2005. Golden jackal. Canids.org. Retrieved March 4, 2019.

- Koepfli, K. P., et al. 2015. Genome-wide Evidence Reveals that African and Eurasian Golden Jackals Are Distinct Species Curr Biol25(16) (2015): 2158-2165. Retrieved March 4, 2019.

- Lindblad-Toh, K., C. M. Wade, T. S. Mikkelsen, et al. 2005. Genome sequence, comparative analysis and haplotype structure of the domestic dog. Nature 438: 803-819. Retrieved March 4, 2019.

- Loveridge, A. J., and J. A. J. Nel. 2005. Black-backed jackal. Canids.org. Retrieved March 4, 2019.

- Macdonald, D. 2001. The New Encyclopedia of Mammals. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198508239.

- Macdonald, D. 1992. The Velvet Claw: A Natural History of the Carnivores. BBC Books. ISBN 0563208449.

- Owens, M., and D. Owens. 1984. Cry of the Kalahari. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0395322146.

- Wozencraft, W. C. 2005. In D. E. Wilson, and D. M. Reeder (eds.). Mammal Species of the World, 3rd edition. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0801882214.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Jackal history

- Golden_Jackal history

- Side-striped_Jackal history

- Black-backed_Jackal history

- Ethiopian_Wolf history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.