Hornet

| Hornet | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Oriental hornet, Vespa orientalis

| ||||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||

|

See text |

Hornet is the common name for any of the large, eusocial stinging wasps comprising the genus Vespa of the subfamily Vespinae and family Vespidae, characterized by a proportionally larger vertex (part of the head behind the eyes) than other vespines, and by anteriorly rounded gasters (the section of the abdomen behind the wasp waist). Hornets are the largest eusocial wasps, reaching up to 45 millimeters (1.8 inches) in length. There are about 20 species in Vespa, found in Asia, Europe, Africa, and one introduced species in North America.

Hornets typically build aerial nests. Unlike honeybees, hornet and yellowjacket colonies die out every winter.

While the "true hornets" make up the genus Vespa, they are wasps in other genera that also have the common name of hornet. Members of Vespula and its sister genus Dolichovespula, although generally known as yellowjackets, are sometimes referred to as hornets, such as Dolichovespula maculata, the "bald-faced hornet." Another example is the Australian hornet (Abispa ephippium), which is actually a species of potter wasp. This article will be limited to the true hornets of the Vespa genus.

Although the sting of a hornet can pose risks for humans, particularly if there is an allergic reaction or the entire nest is mobilized in defense, hornets also provide important functions. In particular, hornets (and yellowjackets} prey on many insects that are considered to be pests, so they are actually beneficial. Hornets capture only live insects, including nocturnal insects, and, thus, are a natural control device. In particular they capture flies. Although hornets capture some bees, including honeybees, the impact on the bee population is generally negligible. Because of their beneficial nature, the common Vespa crabro is actually a protected species in Germany.

Overview and description

Hornets are members of Vespidae, a large, diverse, cosmopolitan family of nearly 5,000 species of wasps, including nearly all the known eusocial wasps and many solitary wasps. There are two subfamilies composed solely of eusocial species, Polistinae and Vespinae, with hornets composing part of Vespinae. In Vespinae, as with Polistinae, rather than consuming prey directly, prey are masticated and fed to the larvae. The larva, in return, produce a clear liquid (with high amino acid content) that the adults consume; the exact amino acid composition varies considerably among species, but it is considered to contribute substantially to adult nutrition (Hunt et al. 1982).

True hornet comprise the genus Vespa. While taxonomically well-defined, there may be some ambiguity about the differences between hornets and other wasps of the family Vespidae, specifically the yellowjackets, which are members of the same subfamily. Yellowjackets are generally smaller than hornets and are bright yellow and black, whereas hornets may be darker in color. Hornets also are characterized by the section of the abdomen after the waist (gaster) being more rounded in the front, and by the part of the head behind the eyes (vertex) being proportionally larger.

Another major difference between yellowjackets and hornets are their food choices and aggression towards humans. In the fall, yellowjackets may be attracted to human foods and food wastes, increasing potentially aggressive contact between yellowjackets and humans. Hornets, on the other hand, tend to stick to live insects.

The large North American species Dolichovespula maculata, which also is referred to a a hornet (bald-faced hornet), is set apart from true hornets in Vespa by its black and ivory coloration. The name "hornet" is used for this and related species primarily because of their habit of making aerial nests (similar to the true hornets) rather than subterranean nests.

Geographical distribution

Most species of Vespa are native to tropical and desert southern Asia, but there is one widespread species, the European hornet (V. crabro), that is found across temperate Eurasia from Britain to Japan. Another widespread species, the Oriental hornet (V. orientalis), extends via southern and central Asia to the Arabian peninsula, up to northern and eastern Africa and the Mediterranean basin (including southern Italy and Sicily). Another species occurs in temperate eastern Asia, the yellow hornet (V. simillima), and some tropical species also range as far north as China, Siberia, or Japan. The Asian giant hornet (V. mandarinia) is a native of temperate and tropical Asia.

The European hornet was accidentally introduced to North America in 1840 and is now present in many eastern regions; it is the only true hornet in North America (Jacobs 2003). As of 2003, its geographical range extends from the Northeastern United States west to the Dakotas, and south to Louisiana and Florida (Jacobs 2003).

Life cycle

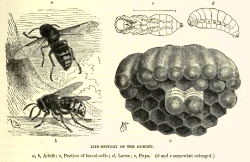

In Vespa crabro, the European hornet, a new nest is founded each spring by a fertilized female, known as the queen, which has survived over the winter. The queen generally selects sheltered places for the nest, such as dark hollow tree trunks. In constructing the nest, the queen first builds a series of cells (up to 50) out of chewed tree bark. The cells are arranged in horizontal layers named combs, with each cell being vertical and closed at the top. An egg is then laid in each cell.

After 5 to 8 days, the egg hatches, and in the next two weeks the larva that emerges will undergo five stages of growth. During this time, the queen feeds it a protein-rich diet of insects. After this period of growth, the larva spins a silk cap over the cell's opening, and during the next two weeks transforms into an adult, a process called metamorphosis. After transforming to an adult, the adult emerges from the cell by eating through the silk cap. This first generation of workers, invariably females, will now gradually undertake all the tasks that were formerly carried out by the queen (foraging, nest building, taking care of the brood, and so on) with one exception: Egg-laying, which remains exclusive to the queen.

As the colony size grows, new combs are added, and an envelope is built around the cell layers, until the nest is entirely covered, with the exception of an entry hole. At the peak of its population, the colony can reach a size of 700 workers. This occurs in late summer.

At this time, the queen starts producing the first reproductive individuals. Fertilized eggs develop into females (called "gynes" by entomologists), unfertilized ones into males (sometimes called "drones"). Adult males do not participate in nest maintenance, foraging, or caretaking of the larvae. In early to mid-autumn, the males and females leave the nest and mate during "nuptial flights." Males die shortly after mating. The workers and unfertilized queens survive at most until mid to late autumn; only the fertilized queens survive over winter.

Other temperate species (for example, the yellow hornet, V. simillima, or the Oriental hornet, V. orientalis) have similar cycles. In the case of tropical species (for example, V. tropica), life histories may well differ; and in species with both tropical and temperate distributions (such as the Asian giant hornet, Vespa mandarinia), it is conceivable that the cycle depends on latitude.

Worker tasks

The workers accomplish a variety of tasks during the colony's lifetime. These include:

- Foraging. Workers feed mainly on carbohydrate-rich fluids, such as tree sap. They also hunt other insects, primarily flies but also other species including smaller wasps and bees; they have been known to attack dragonflies. After subduing the prey, the hornet may discard all nutrient-poor parts such as the wings, legs, head, and/or abdomen. This leaves only the thorax with the protein-rich flight muscles, which constitutes the main food of the larvae. On hot days, workers will bring water to the nest and deposit it on the envelope, thus cooling the interior.

- Expanding and rearranging the nest. This includes building new combs and new cells.

- Feeding the larvae. On returning back to the nest, masticated prey flesh is fed to the larvae, which have higher protein needs (for growth) than the workers, since they no longer grow. The larvae, in turn, produce a nutrient fluid, rich in amino acids, which is consumed by the adults, especially the queen.

Stings

A hornet's sting is painful to humans, but the sting toxicity varies greatly by hornet species. Some deliver just a typical insect sting, while others are among the most venomous known insects (Schmidt et al. 1986). Allergic reactions, fatal in severe cases, can occur—an individual suffering from anaphylactic shock may die unless treated immediately via epinephrine (adrenaline) injection using a device such as an EpiPen, with prompt followup treatment in a hospital.

- European hornet sting

- In itself is not fatal except sometimes to allergic victims (Schmidt et al. 1986)

- Multiple stings (several hundred) may be fatal due to the amount of venom (similar to wasps and bees)

- Is less toxic than a bee sting

- Non-European hornet sting

- In itself is not fatal except sometimes to allergic victims (Schmidt et al. 1986)

- Multiple stings (a nest full) can be fatal due to highly toxic species-specific additions in the venom (Barss 1989)

- Is more toxic than a typical wasp's or bee's sting

- From the Asian giant hornet (Vespa mandarinia japonica) is the most venomous known (per sting) (Schmidt et al. 1986)

- All hornet stings

- Are an allergen for people with an allergy to wasp venom

- Those allergic to wasp venom are not necessarily allergic to bee venom as they contain different chemicals

- Contain less volume of venom than a bee sting

- Are primarily for killing insect prey

- Are more painful than a typical wasp's due to a large amount (5 percent) of acetylcholine (Bhoola et al. 1961)

As in all stinging wasps, hornets can sting multiple times. They do not die after stinging a human, as is typical for a worker honeybee, as the hornet sting is not barbed. (The honeybee's barbed stinger is used for defending the nest against vertebrates/mammals and will pull free, along with the associated venom sac, from the honeybee's body.) Hornets also can bite and sting at the same time.

Alarm escalation

Hornets, like many social wasps, can mobilize the entire nest to sting in defense. The hornet alarm pheromone is used to raise alarm of nest attack, and to identify prey, for example bees (Voith 2006).

Alarm escalation can be highly dangerous to humans. It is not advisable to kill a hornet anywhere near a nest, as the distress signal can trigger the entire nest to attack. Materials that come in contact with pheromone, such as clothes, skin, dead prey, or hornets, must be removed from the vicinity of the hornets nest. Perfumes, and other volatile chemicals can be falsely identified as pheromone by the hornets and trigger an attack (Voith 2006).

Actions to avoid include:

- Disturbing a nest (including vibrations and loud noises)

- Being within a few meters of a nest

- Disturbing or killing a hornet within a few meters of a nest

- Blocking the path of a hornet

- Breathing on the nest or hornet

- Rapid air movements

Species

- Vespa affinis

- Vespa analis

- Vespa auraria

- Vespa basalis

- Vespa bellicosa

- Vespa bicincta

- Vespa bicolor

- Vespa binghami

- Vespa crabro

- Vespa ducalis

- Vespa dybowskii

- Vespa fervida

- Vespa fumida

- Vespa luctuosa

- Vespa mandarinia

- Vespa mocsaryana

- Vespa multimaculata

- Vespa orientalis

- Vespa philippinensis

- Vespa simillima

- Vespa soror

- Vespa tropica

- Vespa velutina

- Vespa vivax

Notable species

- Asian giant hornet Vespa mandarinia

- Vespa mandarinia japonica (sometimes known as Japanese giant hornet)—the largest wasp, and the most venomous known insect (per sting) (Schmidt et al. 1986).

- Black-bellied hornet Vespa basalis

- European hornet Vespa crabro (sometimes known as Old World hornet, or brown hornet).

- Greater banded hornet Vespa tropica

- Japanese hornet Vespa simillima (sometimes known as Japanese yellow hornet).

- Lesser banded hornet Vespa affinis

- Oriental hornet Vespa orientalis

- Yellow-legged hornet Vespa velutina

- Vespa luctuosa the most lethal wasp venom (per volume) (Schmidt et al. 1986).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Barss, P. 1989. Renal failure and death after multiple stings in Papua New Guinea. Ecology, prevention and management of attacks by vespid wasps. Med J Aust. 151(11-12): 659–63.

- Bhoola, K. D., J. D. Calle, and M. Schachter. 1961. Identification of acetylcholine, 5-hydroxytryptamine, histamine, and a new kinin in hornet venom (V. crabro). J Physiol. 159(1): 167–182.

- Hunt, J. H., I. Baker, and H. G. Baker. 1982. Similarity of amino acids in nectar and larval saliva: the nutritional basis for trophallaxis in social wasps. Evolution 36: 1318-1322.

- Jacobs, S. 2003. European hornet. Penn State Entomology Department Fact Sheet. Retrieved November 6, 2018.

- Schmidt, J. O., S. Yamane, M. Matsuura, and C. K. Starr. 1986. Hornet venoms: Lethalities and lethal capacities. Toxicon 24(9): 950–4. Retrieved November 6, 2018.

- Voith, M. 2006. Gee, your hair smells dangerous. Volatile fragrance chemicals may attract unwanted attention from hornets and bees. Chemical & Engineering News. Retrieved November 6, 2018.

External links

All links retrieved July 19, 2024.

- Bees, Hornets, and Wasps of the World

- Hornets National Geographic

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.