Lion

| Lion[1]

| ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Male

Female (Lioness)

| ||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| Panthera leo (Linnaeus, 1758) | ||||||||||||||

Distribution of lions in Africa

| ||||||||||||||

Distribution of lions in India. The Gir Forest, in the State of Gujarat, is the last natural range of approximately 300 wild Asiatic Lions.

| ||||||||||||||

|

Linnaeus, 1758 |

The lion (Panthera leo) is an Old World mammal of the Felidae family and one of the four species of "big cats" (subfamily Pantherinae) in the Panthera genus, along with the tiger (P. tigris), the leopard (P. pardus), and the jaguar (P. onca). The lion is the second-largest living cat after the tiger, with some males exceeding 250 kilograms (550 pounds). It is the only felid with a tufted tail and the male is uniquely characterized by a mane.

Wild lions currently exist mainly in Sub-Saharan Africa, with a critically endangered remnant population in northwest India in Asia, having disappeared from North Africa, the Middle East, and Western Asia in historic times. Until the late Pleistocene (about 10,000Â years ago), the lion was the most widespread large land mammal after humans. They were found in most of Africa, much of Eurasia from western Europe to India, and in the Americas from the Yukon to Peru.

Lions typically inhabit savanna and grassland, although they may take to bush and forest. Lions are unusually social compared to other cats. A pride of lions consists of related females and offspring and a small number of adult males. Groups of female lions typically hunt together, preying mostly on large ungulates.

Lions provide important ecological and cultural functions. As an apex and keystone predator, lions help to regulate prey populations; they also will scavenge if the opportunity arises. Culturally, the lion (and particularly the male with its highly distinctive mane) is one of the most widely recognized animal symbols in human culture. Depictions have existed from the Upper Paleolithic period, with carvings and paintings from the Lascaux and Chauvet Caves, through virtually all ancient and medieval cultures where they historically occurred. The lion has been extensively depicted in literature, in sculptures, in paintings, on national flags, and in contemporary films and literature. Lions have been kept in menageries since Roman times and have been a key species sought for exhibition in zoos the world over since the late eighteenth century.

The lion is a Vulnerable species, having seen a possibly irreversible population decline of 30 to 50 percent over the past two decades in its African range. Lion populations are untenable outside of designated reserves and national parks. Although the cause of the decline is not fully understood, habitat loss and conflicts with humans are currently the greatest causes of concern. Zoos are cooperating worldwide in breeding programs for the endangered Asiatic subspecies.

Physical characteristics

The lion is the tallest (at the shoulder) of the felines and also is the second-heaviest feline after the tiger. With powerful legs, a strong jaw, and 8 centimeter (3.1 inch) long canine teeth, the lion can bring down and kill large prey.

The skull of the lion is very similar to that of the tiger, though the frontal region is usually more depressed and flattened, with a slightly shorter postorbital region. The lion's skull has broader nasal openings than the tiger. However, due to the amount of skull variation in the two species, usually only the structure of the lower jaw can be used as a reliable indicator of species.[3]

The top row of whiskers form a pattern that differs in every lion; this unique pattern, known as "whisker spots," is used by researchers to identify specific animals in the field.[4]

The most distinctive characteristic shared by both females and males is that the tail ends in a hairy tuft. In some lions, the tuft conceals a hard "spine" or "spur," approximately 5 millimeters long, formed of the final sections of tail bone fused together. The lion is the only felid to have a tufted tailâthe function of the tuft and spine are unknown. Absent at birth, the tuft develops around 5œ months of age and is readily identifiable at 7 months.[5]

Lions are the only members of the cat family to display obvious sexual dimorphismâthat is, males and females look distinctly different. They also have specialized roles that each gender plays in the pride. For instance, the lioness, the hunter, lacks the male's thick cumbersome mane. It seems to impede the male's ability to be camouflaged when stalking the prey and creates overheating in chases. The color of the male's mane varies from blond to black, generally becoming darker as the lion grows older.

Coloration

Lion coloration varies from light buff to yellowish, reddish, or dark ochraceous brown. The underparts are generally lighter and the tail tuft is black. Lion cubs are born with brown rosettes (spots) on their body, rather like those of a leopard. Although these fade as lions reach adulthood, faint spots often may still be seen on the legs and underparts, particularly on lionesses.

The white lion is not a distinct subspecies, but a special morph with a genetic condition, leucism, that causes paler coloration akin to that of the white tiger; the condition is similar to melanism, which causes black panthers. They are not albinos, having normal pigmentation in the eyes and skin. The unusual cream color of their coats is due to a recessive gene.[6]

Size

Weights for adult lions generally lie between 150 to 250 kilograms (330â550 pounds) for males and 120 to 182 kilograms (264â400 pounds) for females.[7] Nowell and Jackson report average weights of 181 kilograms for males and 126 kilograms for females; one male shot near Mount Kenya was weighed at 272 kilograms (600 pounds).[8] Lions tend to vary in size depending on their environment and area, resulting in a wide spread in recorded weights. For instance, lions in southern Africa tend to be about 5 percent heavier than those in East Africa, in general.[9]

Head and body length ranges from about 170 to 250 centimeters (5Â ft 7Â in â 8Â ft 2Â in) in males and 140 to 175 centimeters (4Â ft 7Â in â 5Â ft 9Â in) in females; shoulder height is about 123Â centimeters (4Â ft) in males and 107Â centimeters (3Â ft 6Â in) in females. The tail length is 90 to 105Â centimeters (2 ft 11 in - 3 ft 5 in) in males and 70â100Â centimeters in females (2Â ft 4Â in â 3Â ft 3Â in).[7] The longest known lion was a black-maned male shot near Mucsso, southern Angola in October 1973; the heaviest known lion was a man-eater shot in 1936 just outside Hectorspruit in eastern Transvaal, South Africa and weighed 313Â kilograms (690 lb).[10] Lions in captivity tend to be larger than lions in the wild: the heaviest lion on record is a male at Colchester Zoo in England named Simba in 1970, who weighed 375Â kilograms (826 pounds).[10]

Mane

The mane of the adult male lion, unique among cats, is one of the most distinctive characteristics of the species. The mane makes the lion appear larger, providing an excellent intimidation display; this is believed to aid the lion during confrontations with other lions and with the species' chief competitor in Africa, the spotted hyena.

The presence, absence, color, and size of the mane is associated with genetic precondition, sexual maturity, climate, and testosterone production; the rule of thumb is the darker and fuller the mane, the healthier the lion.

Sexual selection of mates by lionesses appears to favor males with the densest, darkest mane.[11] Research in Tanzania also suggests mane length signals fighting success in male-male confrontations. Darker-maned individuals may have longer reproductive lives and higher offspring survival, although they suffer in the hottest months of the year.[12] In prides including a coalition of two or three males, it is possible that lionesses solicit mating more actively with the males who are more heavily maned.

Scientists once believed that the distinct status of some subspecies could be justified by morphology, including the size of the mane. Morphology was used to identify subspecies such as the Barbary lion and Cape lion. Research has suggested, however, that environmental factors influence the color and size of a lion's mane, such as the ambient temperature.[12] The cooler ambient temperature in European and North American zoos, for example, may result in a heavier mane. Thus, the mane is not an appropriate marker for identifying subspecies.[13] The males of the Asiatic subspecies, however, are characterized by sparser manes than average African lions.[14]

Not all male lions have manes. Maneless male lions have been reported in Senegal and Tsavo East National Park in Kenya, and the original male white lion from Timbavati also was maneless. Castrated lions have minimal manes. The lack of a mane sometimes is found in inbred lion populations; inbreeding also results in poor fertility.

Many lionesses have a ruff that may be apparent in certain poses. Sometimes it is indicated in sculptures and drawings, especially ancient artwork, and is misinterpreted as a male mane. It differs from a mane, however, in being at the jaw line below the ears, of much less hair length, and frequently not noticeable, whereas a mane extends above the ears of males, often obscuring their outline entirely.

Cave paintings of extinct European cave lions exclusively show animals with no mane, or just the hint of a mane, suggesting to some that they were more or less maneless;[15] however, females hunting for a pride are the likely subjects of the drawingsâsince they are shown in a group related to huntingâso these images do not enable a reliable judgment about whether the males had manes. The drawings do suggest that the extinct species used the same social organization and hunting strategies as contemporary lions.

Distribution and habitat

Today, lions are largely limited to Africa, with a smaller population in India.

In relatively recent times, the distribution of lions spanned the southern parts of Eurasia, ranging from Greece to India, and most of Africa except the central rainforest zone and the Sahara desert. Herodotus reported that lions had been common in Greece around 480 B.C.E.; they attacked the baggage camels of the Persian king Xerxes on his march through the country. Aristotle considered them rare by 300 B.C.E. and by 100 C.E. extirpated.[5] A population of the Asiatic lion survived until the tenth century in the Caucasus, their last European outpost.[3]

The species was eradicated from Palestine by the Middle Ages and from most of the rest of Asia after the arrival of readily available firearms in the eighteenth century. Between the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, they became extinct in North Africa and the Middle East. By the late nineteenth century, the lion had disappeared from Turkey and most of northern India,[16] while the last sighting of a live Asiatic lion in Iran was in 1941 (between Shiraz and Jahrom, Fars Province), though the corpse of a lioness was found on the banks of Karun river, KhĆ«zestÄn Province in 1944. There are no subsequent reliable reports from Iran.

They were found in most of Africa, much of Eurasia from western Europe to India and the Bering land bridge, and in the Americas from Yukon to Peru.[17] Parts of this range were occupied by subspecies that are extinct today.

In Africa, lions can be found in savanna grasslands with scattered Acacia trees, which serve as shade;[18]. In India, their habitat is a mixture of dry savanna forest and very dry deciduous scrub forest.[19]

Behavior, diet, and reproduction

Lions spend much of their time resting and are inactive for about 20Â hours per day.[5] Although lions can be active at any time, their activity generally peaks after dusk with a period of socializing, grooming, and defecating. Intermittent bursts of activity follow through the night hours until dawn, when hunting most often takes place. They spend an average of two hours a day walking and 50Â minutes eating.[5]

Group organization

Lions are predatory carnivores who manifest two types of social organization.

The first type of social organization is that of "residents," who live in groups, called "prides."[5] The pride usually consists of approximately five or six related females, their cubs of both sexes, and one or two males (known as a coalition if more than one) who mate with the adult females. However, extremely large prides, consisting of up to 30 individuals, have been observed. The coalition of males associated with a pride usually amounts to two, but may increase to four and decrease again over time. Male cubs are excluded from their maternal pride when they reach maturity.

The second organizational behavior is labeled nomads, who range widely and move about sporadically, either singularly or in pairs.[5] Pairs are more frequent among related males who have been excluded from their birth pride. Note that a lion may switch lifestyles; nomads may become residents and vice versa. Males have to go through this lifestyle and some never are able to join another pride. A female who becomes a nomad has much greater difficulty joining a new pride, as the females in a pride are related, and they reject most attempts by an unrelated female to join their family group.

The area a pride occupies is called a pride area, whereas that by a nomad is a range.[5] The males associated with a pride tend to stay on the fringes, patrolling their territory.

Why socialityâthe most pronounced in any cat speciesâhas developed in lionesses is the subject of much debate. Increased hunting success appears an obvious reason, but this is less than sure upon examination: coordinated hunting does allow for more successful predation, but also means that non-hunting members will reduce per capita caloric intake. (Non-hunting members include those who take a role raising cubs, who may be left alone for extended periods of time. Members of the pride regularly tend to play the same role in hunts.) The health of the hunters is the primary need for the survival of the pride and they are the first to consume the prey at the site it is taken. Other benefits include possible kin selection (better to share food with a related lion than with a stranger), protection of the young, maintenance of territory, and individual insurance against injury and hunger.[8]

Lionesses do the majority of the hunting for their pride, being smaller, swifter, and more agile than the males, and unencumbered by the heavy and conspicuous mane, which causes overheating during exertion. They act as a coordinated group in order to stalk and bring down the prey successfully. Smaller prey is eaten at the location of the hunt, thereby being shared among the hunters; when the kill is larger it often is dragged to the pride area. There is more sharing of larger kills,[5] although pride members often behave aggressively toward each other as each tries to consume as much food as possible. If males are near the hunt, the males have a tendency to dominate the kill once the lionesses have succeeded and eaten. They are more likely to share with the cubs than with the lionesses, but rarely share food they have killed by themselves.

Both males and females defend the pride against intruders. Some individual lions consistently lead the defense against intruders, while others lag behind.[20] Lions tend to assume specific roles in the pride. Those lagging behind may provide other valuable services to the group.[21] An alternative hypothesis is that there is some reward associated with being a leader who fends off intruders and the rank of lionesses in the pride is reflected in these responses.[22] The male or males associated with the pride must defend their relationship to the pride from outside males who attempt to take over their relationship with the pride. Females form the stable social unit in a pride and do not tolerate outside females; membership only changes with the births and deaths of lionesses, although some females do leave and become nomadic. Subadult males on the other hand, must leave the pride when they reach maturity at around 2â3 years of age.[5]

Diet and hunting

Lion's prey consists mainly of large mammals, with a preference for wildebeest, impalas, zebras, buffalo, and warthogs in Africa and nilgai, wild boar, and several deer species in India. Many other species are hunted, based on availability. Mainly this will include ungulates, such as kudu, hartebeest, gemsbok, and eland.[7] Extensive statistics collected over various studies show that lions normally feed on mammals in the range 190 to 550 kilograms (420-1210 pounds). Wildebeest rank at the top of preferred prey (making nearly half of the lion prey in the Serengeti) followed by zebra.[23] and smaller gazelles, impala, and other agile antelopes are generally excluded. Even though smaller than 190Â kilograms (420Â lb), warthogs are often taken depending on availability.[24] Occasionally, lions take relatively small species such as Thomson's Gazelle or springbok. Lions living near the Namib coast feed extensively on seals.

Lions hunting in groups are capable of taking down most animals, even healthy adults, but in most parts of their range they rarely attack very large prey, such as fully grown male giraffes, due to the danger of injury. Most adult hippopotamuses, rhinoceroses, and elephants are also excluded. However giraffes and buffaloes are often taken in certain regions. For instance, in Kruger National Park, giraffes are regularly hunted,[25] and in Manyara Pack, Cape buffaloes constitute as much as 62 percent of the lion's diet, due to the high density of buffaloes.[26] Occasionally hippopotamus also is taken, but adult rhinoceroses are generally avoided. In the Savuti river, lions are known to prey on elephants. Park guides in the area reported that the lions, driven by extreme hunger, started taking down baby elephants, and then moved on to adolescents and, occasionally, fully grown adults during the night when elephants' vision is poor.[27]

Lions also attack domestic livestock; in India, cattle contribute significantly to their diet. They are capable of killing other predators such as leopards, cheetahs, hyenas, and wild dogs, though (unlike most felids) they seldom devour the competitors after killing them. They also scavenge animals either dead from natural causes or killed by other predators, and keep a constant lookout for circling vultures, being keenly aware that they indicate an animal dead or in distress.[5]

A lion may gorge itself and eat up to 30 kilograms (66 pounds) in one sitting;[28] if it is unable to consume all the kill it will rest for a few hours before consuming more. On a hot day, the pride may retreat to shade leaving a male or two to stand guard.[5] An adult lioness requires an average of about 5 kilograms (11 pounds) of meat per day, a male about 7 kilograms (15.4 pounds).[4]

Lions are powerful animals who usually hunt in coordinated groups and stalk their chosen prey. However, they are not particularly known for their stamina. For instance, a lioness' heart makes up only 0.57 percent of her body weight (a male's is about 0.45 percent of his body weight), whereas a hyena's heart is close to 1 percent of its body weight. Thus, although lionesses can reach speeds of 60 kilometers per hour (40 mph), they only can do so for short bursts, so they have to be close to their prey before starting the attack. They take advantage of factors that reduce visibility; many kills take place near some form of cover or at night.[5] They sneak up to the victim until they reach a distance of approximately 30 meters (98 feet) or less.

Because lions hunt in open spaces where they are easily seen by their prey, cooperative hunting increases the likelihood of a successful hunt; this is especially true with larger species. Teamwork also enables them to defend their kills more easily against other large predators such as hyenas, which may be attracted by vultures from kilometers away in open savannas.

Lionesses do most of the hunting; males attached to prides do not usually participate in hunting, except in the case of larger quarry such as giraffe and buffalo. In typical hunts, each lioness has a favored position in the group, either stalking prey on the "wing" then attacking, or moving a smaller distance in the center of the group and capturing prey in flight from other lionesses.[29]

Typically, several lionesses work together and encircle the herd from different points. Once they have closed with a herd, they usually target the closest prey. The attack is short and powerful; they attempt to catch the victim with a fast rush and final leap. The prey usually is killed by strangulation, which can cause cerebral ischemia or asphyxia (which results in hypoxemic, or "general," hypoxia). The prey also may be killed by the lion enclosing the animal's mouth and nostrils in its jaws (which would also result in asphyxia). Smaller prey, though, may simply be killed by a swipe of a lion's paw.[7]

Young lions first display stalking behavior around three months of age, although they do not participate in hunting until they are almost a year old. They begin to hunt effectively when nearing the age of two.[5]

Reproduction and life cycle

Lions live for around 10 to 14 years in the wild, while in captivity they can live over 20 years. In the wild, males seldom live longer than ten years as fights with rivals occasionally cause injuries.[30]

Most lionesses will have reproduced by the time they are four years of age. Lions do not mate at any specific time of year, and the females are polyestrous.[5] As with other cats, the male lion's penis has spines that point backwards. Upon withdrawal of the penis, the spines rake the walls of the female's vagina, which may cause ovulation.[31] A lioness may mate with more than one male when she is in heat;[5] during a mating bout, which could last several days, the couple copulates twenty to forty times a day and are likely to forgo eating. Lions reproduce very well in captivity.

The average gestation period is around 110Â days,[5] the female giving birth to a litter of one to four cubs in a secluded den (which may be a thicket, a reed-bed, a cave, or some other sheltered area) usually away from the rest of the pride. She will often hunt by herself while the cubs are still helpless, staying relatively close to the thicket or den where the cubs are kept.[9]

The cubs themselves are born blind: Their eyes do not open until roughly a week after birth. They weigh 1.2 to 2.1 kilograms (2.6â4.6Â pounds) at birth and are almost helpless, beginning to crawl a day or two after birth and walking around three weeks of age.[5] The lioness moves her cubs to a new den site several times a month, carrying them one by one by the nape of the neck, to prevent scent from building up at a single den site and thus avoiding the attention of predators that may harm the cubs.[9]

Usually, the mother does not integrate herself and her cubs back into the pride until the cubs are six to eight weeks old.[9] However, sometimes this introduction to pride life occurs earlier, particularly if other lionesses have given birth at about the same time. For instance, lionesses in a pride often have synchronized reproductive cycles, which allows them to cooperate in the raising and suckling of the young (once the cubs are past the initial stage of isolation with their mother). Such young will suckle indiscriminately from any or all of the nursing females in the pride. In addition to greater protection, the synchronization of births also has an advantage in that the cubs end up being roughly the same size, and thus have an equal chance of survival. If one lioness gives birth to a litter of cubs a couple of months after another lioness, for instance, then the younger cubs, being much smaller than their older brethren, are usually dominated by larger cubs at mealtimesâconsequently, death by starvation is more common among the younger cubs.

In addition to starvation, cubs also face many other dangers, such as predation by jackals, hyenas, leopards, eagles, and snakes. Even buffaloes, should they catch the scent of lion cubs, often stampede towards the thicket or den where they are being kept, doing their best to trample the cubs to death while warding off the lioness. Furthermore, when one or more new males oust the previous male(s) associated with a pride, the conqueror(s) often kill any existing young cubs,[32] perhaps because females do not become fertile and receptive until their cubs mature or die. All in all, as many as 80 percent of the cubs will die before the age of two.[33]

When first introduced to the rest of the pride, the cubs initially lack confidence when confronted with adult lions other than their mother. However, they soon begin to immerse themselves in the pride life, playing among themselves or attempting to initiate play with the adults. Lionesses with cubs of their own are more likely to be tolerant of another lioness's cubs than lionesses without cubs. The tolerance of the male lions towards the cubs varies: sometimes, a male will patiently let the cubs play with his tail or his mane, whereas another may snarl and bat the cubs away.[9]

Weaning occurs after six to seven months. Male lions reach maturity at about 3 years of age and, at 4 to 5 years of age, are capable of challenging and displacing the adult male(s) associated with another pride. They begin to age and weaken between 10 and 15 years of age at the latest, if they have not already been critically injured while defending the pride. (Once ousted from a pride by rival males, male lions rarely manage a second take-over.) This leaves a short window for their own offspring to be born and mature. If they are able to procreate as soon as they take over a pride, they may have more offspring reaching maturity before they also are displaced. A lioness often will attempt to defend her cubs fiercely from a usurping male, but such actions are rarely successful. He usually kills all of the existing cubs who are less than two years old. A lioness is weaker and much lighter than a male; success is more likely when a group of three or four mothers within a pride join forces against one male.[32]

Contrary to popular belief, it is not only males that are ousted from their pride to become nomads, although the majority of females certainly do remain with their birth pride. However, when the pride becomes too large, the next generation of female cubs may be forced to leave to eke out their own territory. Furthermore, when a new male lion takes over the pride, subadult lions, both male and female, may be evicted.<[9] Life is harsh for a female nomad. Nomadic lionesses rarely manage to raise their cubs to maturity, without the protection of other pride members.

Though adult lions have no natural predators, evidence suggests that the majority die violently from humans or other lions.[5] This is particularly true of male lions, who, as the main defenders of the pride, are more likely to come into aggressive contact with rival males. In fact, even though a male lion may reach an age of 15 or 16 years if he manages to avoid being ousted by other males, the majority of adult males do not live to be more than 10 years old. This is why the average lifespan of a male lion tends to be significantly less than that of a lioness in the wild. However, members of both sexes can be injured or even killed by other lions when two prides with overlapping territories come into conflict.

Communication

When resting, lion socialization occurs through a number of behaviors, and the animal's expressive movements are highly developed. The most common peaceful tactile gestures are head rubbing and social licking,[5] which have been compared with grooming in primates.[34] Head rubbingânuzzling one's forehead, face, and neck against another lionâappears to be a form of greeting, as it is seen often after an animal has been apart from others, or after a fight or confrontation. Males tend to rub other males, while cubs and females rub females. Social licking often occurs in tandem with head rubbing; it is generally mutual and the recipient appears to express pleasure. The head and neck are the most common parts of the body licked, which may have arisen out of utility, as a lion cannot lick these areas individually.[5]

Lions have an array of facial expressions and body postures that serve as visual gestures. Their repertoire of vocalizations is also large; variations in intensity and pitch, rather than discrete signals, appear central to communication. Lion sounds include snarling, purring, hissing, coughing, miaowing, woofing, and roaring. Lions tend to roar in a very characteristic manner, starting with a few deep, long roars that trail off into a series of shorter ones. They most often roar at night; the sound, which can be heard from a distance of 8 kilometers (5 miles), is used to advertise the animal's presence.[5] Lions have the loudest roar of any big cat.

Interspecific predatory relationships

The relationship between lions and spotted hyenas in areas where they coexist is unique in its complexity and intensity. Lions and spotted hyenas are both apex predators that feed on the same prey, and are therefore in direct competition with one another. As such, they will often fight over and steal each others' kills. Though hyenas are popularly assumed to be opportunistic scavengers profiting from the lion's hunting abilities, it is quite often the case that the reverse is true. In Tanzania's Ngorongoro Crater, the spotted hyena population greatly exceeds that of the resident lions, which obtain a large proportion of their food by stealing hyena prey.

The feud between the two species, however, extends beyond battles over food. In animals, it is usually the case that territorial boundaries of another species are disregarded. Hyenas and lions are an exception to this; they set boundaries against each other as they would against members of their own species. Male lions in particular are extremely aggressive toward hyenas, and have been observed to hunt and kill hyenas without eating them. Conversely, hyenas are major predators of lion cubs, and will harass lionesses over kills. However, healthy adult males, even single ones, are generally avoided at all costs.

Lions tend to dominate smaller felines such as cheetahs and leopards in areas where there ranges overlap. They will steal their kills and will kill their cubs and even adults when given the chance. The cheetah has a fifty percent chance of losing its kill to lions or other predators.[35] Lions are major killers of cheetah cubs, up to ninety percent of which are lost in their first weeks of life due to attacks by other predators. Cheetahs avoid competition by hunting at different times of the day and hide their cubs in thick brush. Leopards also use such tactics, but have the advantage of being able to subsist much better on small prey than either lions or cheetahs. Also, unlike cheetahs, leopards can climb trees and use them to keep their cubs and kills away from lions. However, lionesses will occasionally be successful in climbing to retrieve leopard kills.[5]

Similarly, lions dominate African wild dogs, not only taking their kills but also preying on both young and adult dogs (although the latter are rarely caught).

The Nile crocodile is the only sympatric predator (besides humans) that can singly threaten the lion. Depending on the size of the crocodile and the lion, either can lose kills or carrion to the other. Lions have been known to kill crocodiles venturing onto land, while the reverse is true for lions entering waterways containing crocodiles, as evidenced by the fact that lion claws have on occasion been found in crocodile stomachs.[36]

Taxonomy and evolution

The oldest lion-like fossil is known from Laetoli site in Tanzania and is perhaps 3.5Â million years old; some scientists have identified the material as Panthera leo. These records are not well-substantiated, and all that can be said is that they pertain to a Panthera-like felid. The oldest confirmed records of Panthera leo in Africa are about 2Â million years younger.[37]

The closest relatives of the lion are the other Panthera species: the tiger, the jaguar, and the leopard. Morphological and genetic studies suggest that the tiger was the first of these recent species to diverge. About 1.9Â million years ago the jaguar branched off the remaining group, which contained ancestors of the leopard and lion. The lion and leopard subsequently separated about 1 to 1.25Â million years ago from each other.[38]

Panthera leo itself is considered to have evolved in Africa between 1 million and 800,000 years ago, before spreading throughout the Holarctic region.[39] It appeared in Europe for the first time 700,000 years ago with the subspecies Panthera leo fossilis at Isernia in Italy. From this lion there derived the later cave lion (Panthera leo spelaea), which appeared about 300,000 years ago. During the upper Pleistocene the lion spread to North and South America, and there appeared the subspecies Panthera leo atrox, the American lion.[40] Lions died out in northern Eurasia and America at the end of the last glaciation, about 10,000 years ago;[41] this may have been secondary to the extinction of Pleistocene megafauna.

Subspecies

Traditionally, twelve recent subspecies of lion were recognized, the largest of which has been recognized as the Barbary lion. The major differences separating these subspecies are location, mane appearance, size, and distribution. Because these characteristics are insignificant and show high individual variability, most of these forms were debatable and probably invalid as subspecies; additionally, they often were based upon zoo material of unknown origin that may have had "striking, but abnormal" morphological characteristics.[16] Today, typically only eight subspecies are accepted,[41] but one of these (the Cape lion, formerly described as Panthera leo melanochaita) probably is invalid.[13]

Even the remaining seven subspecies might be too many; mitochondrial variation in recent African lions is modest, which suggests that all sub-Saharan lions could be considered a single subspecies, possibly divided in two main clades: one to the west of the Great Rift Valley and the other to the east. Lions from Tsavo in Eastern Kenya are much closer genetically to lions in Transvaal (South Africa), than to those in the Aberdare Range in Western Kenya.[42]

Recent

Eight recent subspecies are recognized today:

- P. l. persica, known as the Asiatic lion or South Asian, Persian, or Indian lion, once was widespread from Turkey, across the Middle East, to Pakistan, India, and even to Bangladesh. However, large prides and daylight activity made them easier to poach than tigers or leopards.

- P. l. leo, known as the Barbary lion, is extinct in the wild due to excessive hunting, although captive individuals may still exist. This was one of the largest of the lion subspecies, with reported lengths of 3 to 3.3 meters (10â10.8Â feet) and weights of more than 200 kilograms (440 lb) for males. They ranged from Morocco to Egypt. The last wild Barbary lion was killed in Morocco in 1922.[8]

- P. l. senegalensis, known as the West African lion, is found in western Africa, from Senegal to Nigeria.

- P. l. azandica, known as the Northeast Congo lion, is found in the northeastern parts of the Congo.

- P. l. nubica, known as the East African or Massai lion, is found in east Africa, from Ethiopia and Kenya to Tanzania and Mozambique.

- P. l. bleyenberghi, known as the Southwest African or Katanga lion, is found in southwestern Africa, Namibia, Botswana, Angola, Katanga (Zaire), Zambia, and Zimbabwe.

- P. l. krugeri, known as the Southeast African lion or Transvaal lion, is found in the Transvaal region of southeastern Africa, including Kruger National Park.

- P. l. melanochaita, known as the Cape lion, became extinct in the wild around 1860. Results of mitochondrial DNA research do not support the status as a distinct subspecies. It seems probable that the Cape lion was only the southernmost population of the extant P. l. krugeri.[13]

Prehistoric

Several additional subspecies of lion existed in prehistoric times:

- P. l. atrox, known as the American lion or American cave lion, was abundant in the Americas from Alaska to Peru in the Pleistocene Epoch until about 10,000 years ago. This form as well as the cave lion sometimes are considered to represent separate species, but recent phylogenetic studies suggest that they are in fact, subspecies of the lion (Panthera leo).[41] One of the largest lion subspecies to have existed, its body length is estimated to have been 1.6 to 2.5Â meters (5â8Â ft).[43]

- P. l. fossilis, known as the Early Middle Pleistocene European cave lion, flourished about 500,000 years ago; fossils have been recovered from Germany and Italy. It was larger than today's African lions, reaching the American cave lion in size[41]

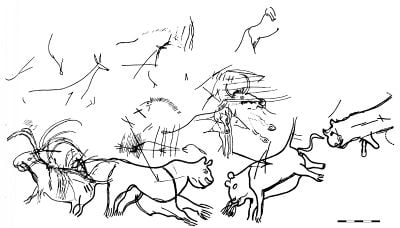

- P. l. spelaea, known as the European cave lion, Eurasian cave lion, or Upper Pleistocene European cave lion, occurred in Eurasia 300,000 to 10,000 years ago.[41] This species is known from Paleolithic cave paintings (such as the one displayed to the right), ivory carvings, and clay busts, [44] indicating it had protruding ears, tufted tails, perhaps faint tiger-like stripes, and that at least some males had a ruff or primitive mane around their necks.[15] With this example being a hunting scene, it is likely that it depicts females hunting for the pride using the same strategy as their contemporary relatives and males may not be part of the subject.

- P. l. vereshchagini, known as the East Siberian- or Beringian cave lion, was found in Yakutia (Russia), Alaska (USA), and the Yukon Territory (Canada). Analysis of skulls and mandibles of this lion demonstrate that it is distinctlyâlarger than the European cave lion and smaller than the American cave lion with differing skull proportions.[41]

Dubious

- P. l. sinhaleyus, known as the Sri Lanka lion, appears to have become extinct approximately 39,000 years ago. It is only known from two teeth found in deposits at Kuruwita. Based on these teeth, P. Deraniyagala established this subspecies in 1939.[45]

- P. l. europaea, known as the European lion, probably was identical with Panthera leo persica or Panthera leo spelea; its status as a subspecies is unconfirmed. It became extinct around 100 C.E. due to persecution and over-exploitation. It inhabited the Balkans, the Italian Peninsula, southern France, and the Iberian Peninsula. It was a very popular object of hunting among Romans, Greeks, and Macedonians.

- P. l. youngi or Panthera youngi, flourished 350,000 years ago.[17] Its relationship to the extant lion subspecies is obscure, and it probably represents a distinct species.

- P. l. maculatus, known as the Marozi or Spotted lion, sometimes is believed to be a distinct subspecies, but may be an adult lion that has retained its juvenile spotted pattern. If it was a subspecies in its own right, rather than a small number of aberrantly colored individuals, it has been extinct since 1931. A less likely identity is a natural leopard-lion hybrid commonly known as a leopon.[46]

Hybrids

Lions have been known to breed with tigers (most often the Siberian and Bengal subspecies) to create hybrids called ligers and tigons.[47] The liger is a cross between a male lion and a tigress.[48] The less common tigon is a cross between the lioness and the male tiger.

Lions also have been crossed with leopards to produce leopons,[49] and jaguars to produce jaglions. The marozi is reputedly a spotted lion or a naturally occurring leopon, while the Congolese Spotted Lion is a complex lion-jaguar-leopard hybrid called a lijagulep. Such hybrids once commonly were bred in zoos, but this is now discouraged due to the emphasis on conserving species and subspecies. Hybrids are still bred in private menageries and in zoos in China.

Population and conservation status

The lion has seen a rapid and possibly irreversible population decline in its African range. Most lions now live in eastern and southern Africa, with an estimated 30 to 50 percent decline over the last two decades.[2]

The remaining populations are often geographically isolated from each other, which can lead to inbreeding, and consequently, a lack of genetic diversity. Therefore the lion is considered a vulnerable species by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources, while the Asiatic subspecies is critically endangered. The lion population in the region of West Africa is isolated from lion populations of Central Africa, with little or no exchange of breeding individuals. The number of mature individuals in West Africa is estimated by two separate recent surveys at 850 to 1,160 (2002/2004). There is disagreement over the size of the largest individual population in West Africa: the estimates range from 100 to 400 lions in Burkina Faso's Arly-Singou ecosystem.[2]

The cause of the decline is not well-understood, and may not be reversible.[2] Currently, habitat loss, and conflicts with humans are considered the most significant threats to the species.[50]

Conservation of both African and Asian lions has required the setup and maintenance of national parks and game reserves; among the best known are Etosha National Park in Namibia, Serengeti National Park in Tanzania, and Kruger National Park in eastern South Africa. Outside these areas, the issues arising from lions' interaction with livestock and people usually results in the elimination of the former. In India, the last refuge of the Asiatic lion is the 1,412Â kmÂČ (558Â square miles) Gir Forest National Park in western India, which had about 359Â lions in 2006. As in Africa, numerous human habitations are close by with the resultant problems between lions, livestock, locals, and wildlife officials.[51] The Asiatic Lion Reintroduction Project plans to establish a second independent population of Asiatic lions at the Kuno Wildlife Sanctuary in the Indian state of Madhya Pradesh.[52] It is important to start a second population to serve as a gene pool for the last surviving Asiatic lions and to help develop and maintain genetic diversity enabling the species to survive.

The former popularity of the Barbary lion as a zoo animal has meant that scattered lions in captivity are likely to be descended from Barbary lion stock.

Lions are one species included in the Species Survival Plan, a coordinated attempt by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums to increase its chances of survival. The plan was originally started in 1982 for the Asiatic lion, but was suspended when it was found that most Asiatic lions in North American zoos were not genetically pure, having been hybridized with African lions. The African lion plan started in 1993, focusing especially on the South African subspecies, although there are difficulties in assessing the genetic diversity of captive lions, since most individuals are of unknown origin, making maintenance of genetic diversity a problem.[16]

Man-eaters

While lions do not usually hunt people, some (usually males) seem to seek out human prey. Well-publicized cases include the Tsavo maneaters, where 28 railway workers building the Kenya-Uganda Railway were taken by lions over nine months during the construction of a bridge over the Tsavo River in Kenya in 1898; and the 1991 Mfuwe man-eater, which killed six people in the Laungwa River Valley in Zambia.[53] In both, the hunters who killed the lions wrote books detailing the animals' predatory behavior. The Mfuwe and Tsavo incidents bear similarities: The lions in both incidents were larger than normal, lacked manes, and seemed to suffer from tooth decay.

A man-eating lion was killed by game scouts in Southern Tanzania in April 2004. It is believed to have killed and eaten at least 35Â people in a series of incidents covering several villages in the Rufiji Delta coastal region. This was attributed by some to the fact that the lion had a large abscess underneath a molar, which was cracked in several places, and probably resulted in a lot of pain, particularly when chewing.[54]

The infirmity theory links lion attacks to physical problems in the lions, including tooth decay, or being sick or injured. However, this theory is not favored by all researchers; An analysis of teeth and jaws of man-eating lions in museum collections suggests that, while tooth decay may explain some incidents, prey depletion in human-dominated areas is a more likely cause of lion predation on humans.[55] In their analysis of Tsavo and man-eating generally, Kerbis Peterhans, and Gnoske acknowledge that sick or injured animals may be more prone to man-eating, but that the behavior is "not unusual, nor necessarily 'aberrant'" where the opportunity exists; if inducements such as access to livestock or human corpses are present, lions will regularly prey upon human beings. The authors note that the relationship is well-attested among other pantherines and primates in the paleontological record.[56]

The lion's proclivity for man-eating has been systematically examined. American and Tanzanian scientists report that man-eating behavior in rural areas of Tanzania increased greatly from 1990 to 2005. At least 563 villagers were attacked and many eaten over this periodâa number far exceeding the more famed "Tsavo" incidents of a century earlier. The incidents occurred near Selous National Park in Rufiji District and in Lindi Province near the Mozambican border. While the expansion of villagers into bush country is one concern, the authors argue that conservation policy must mitigate the danger because, in this case, conservation contributes directly to human deaths. Cases in Lindi have been documented where lions seize humans from the center of substantial villages.[57]

Packer estimates more than 200 Tanzanians are killed each year by lions, crocodiles, elephants, hippos, and snakes, and that the numbers could be double that amount, with lions thought to kill at least 70 of those. Packer and Ikanda are among the few conservationists who believe western conservation efforts must take account of these matters not just because of ethical concerns about human life, but also for the long term success of conservation efforts and lion preservation.[57]

Author Robert R. Frump wrote in The Man-eaters of Eden that Mozambican refugees regularly crossing Kruger National Park at night in South Africa are attacked and eaten by the lions; park officials have conceded that man-eating is a problem there. Frump believes thousands may have been killed in the decades after apartheid policies sealed the park and forced the refugees to cross the park at night. For nearly a century before the border was sealed, Mozambicans had regularly walked across the park in daytime with little harm.[58]

The "All-Africa" record of man-eating generally is considered to be the lesser-known incidents in the late 1930s through the late 1940s in what was then Tanganyika (now Tanzania). George Rushby, game warden and professional hunter, eventually dispatched the pride, which over three generations is thought to have killed and eaten 1,500 to 2,000 in what is now Njombe district.[59]

In captivity

Widely seen in captivity, lions are part of a group of exotic animals that are the core of zoo exhibits since the late eighteenth century. Members of this group are invariably large vertebrates and include elephants, rhinoceroses, hippopotamuses, large primates, and other big cats; zoos sought to gather as many of these species as possible.[60] There are over 1,000 African and 100 Asiatic lions in zoos and wildlife parks around the world. They are considered an ambassador species and are kept for tourism, education, and conservation purposes.

The history of keeping lions in captivity is ancient and extensive. Lions were kept and bred by Assyrian kings as early as 850 B.C.E.,[5] and Alexander the Great was said to have been presented with tame lions by the Malhi of northern India.[61] Later in Roman times, lions were kept by emperors to take part in the gladiator arenas. Roman notables, including Sulla, Pompey, and Julius Caesar, often ordered the mass slaughter of hundreds of lions at a time.[62] In the East, lions were tamed by Indian princes, and Marco Polo reported that Kublai Khan kept lions inside.[63]

The first European "zoos" spread among noble and royal families in the thirteenth century, and until the seventeenth century were called seraglios; at that time, they came to be called menageries, an extension of the cabinet of curiosities. They spread from France and Italy during the Renaissance to the rest of Europe. In England, although the seraglio tradition was less developed, lions were kept at the Tower of London in a seraglio established by King John in the thirteenth century,[63] probably stocked with animals from an earlier menagerie started in 1125 by Henry I at his palace in Woodstock, near Oxford, where lions had been reported stocked by William of Malmesbury.[64]

Seraglios served as expressions of the nobility's power and wealth. Animals such as big cats and elephants, in particular, symbolized power, and would be pitted in fights against each other or domesticated animals. By extension, menageries and seraglios served as demonstrations of the dominance of humanity over nature. Consequently, the defeat of such natural "lords" by a cow in 1682 astonished the spectators, and the flight of an elephant before a rhinoceros drew jeers. Such fights would slowly fade out in the seventeenth century with the spread of the menagerie and their appropriation by the commoners. The tradition of keeping big cats as pets would last into the nineteenth century, at which time it was seen as highly eccentric.[63]

The presence of lions at the Tower of London was intermittent, being restocked when a monarch or his consort, such as Margaret of Anjou, the wife of Henry VI, either sought or were given animals. Records indicate they were kept in poor conditions there in the seventeenth century, in contrast to more open conditions in Florence at the time.[64] The menagerie was open to the public by the eighteenth century; admission was a sum of three half-pence or the supply of a cat or dog for feeding to the lions.[64] A rival menagerie at the Exeter Exchange also exhibited lions until the early nineteenth century.[60] The Tower menagerie was closed down by William IV, and animals transferred to the London Zoo which opened its gates to the public on April 27, 1828.[64]

| Animal species disappear when they cannot peacefully orbit the center of gravity that is man. âPierre-AmĂ©dĂ©e Pichot, 1891[63] |

The wild animals trade flourished alongside improved colonial trade of the nineteenth century. Lions were considered fairly common and inexpensive. Although they would barter higher than tigers, they were less costly than larger, or more difficult to transport animals such as the giraffe and hippopotamus, and much less than pandas. Like other animals, lions were seen as little more than a natural, boundless commodity that was mercilessly exploited with terrible losses in capture and transportation. The widely reproduced imagery of the heroic hunter chasing lions would dominate a large part of the century. Explorers and hunters exploited a popular Manichean division of animals into "good" and "evil" to add thrilling value to their adventures, casting themselves as heroic figures. This resulted in big cats, always suspected of being man-eaters, representing "both the fear of nature and the satisfaction of having overcome it."[63]

Lions were kept in cramped and squalid conditions at London Zoo until a larger lion house with roomier cages was built in the 1870s.[64] Further changes took place in the early twentieth century, when Carl Hagenbeck designed enclosures more closely resembling a natural habitat, with concrete "rocks," more open space, and a moat instead of bars. He designed lion enclosures for both Melbourne Zoo and Sydney's Taronga Zoo, among others, in the early twentieth century. Though his designs were popular, the old bars and cage enclosures prevailed until the 1960s in many zoos.[60]>

In the later decades of the twentieth century, larger, more natural enclosures and the use of wire mesh or laminated glass instead of lowered dens allowed visitors to come closer than ever to the animals, with some attractions even placing the den on ground higher than visitors, such as the Cat Forest/Lion Overlook of Oklahoma City Zoological Park.[16] Lions are now housed in much larger naturalistic areas; modern recommended guidelines more closely approximate conditions in the wild with closer attention to the lions' needs, highlighting the need for dens in separate areas, elevated positions in both sun and shade where lions can sit, and adequate ground cover and drainage as well as sufficient space to roam.

There have also been instances where a lion was kept by a private individual, such as the lioness Elsa, who was raised by George Adamson and his wife Joy Adamson and came to develop a strong bonds with them, particularly the latter. The lioness later achieved fame, her life being documented in a series of books and films.

Baiting and taming

Lion-baiting is a blood sport involving the baiting of lions in combat with other animals, usually dogs. Records of it exist in ancient times up to the nineteenth century; it was banned in Vienna in 1800 and in England in 1825.

Lion taming refers to the practice of taming lions for entertainment, either as part of an established circus or as an individual act. The term also often is used for the taming and display of other big cats, such as tigers, leopards, and cougars. The practice was pioneered in the first half of the nineteenth century by Frenchman Henri Martin and American Isaac Van Amburgh who both toured widely, and whose techniques were copied by a number of followers. Van Amburgh performed before Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom in 1838 when he toured Great Britain. Martin composed a pantomime titled Les Lions de Mysore ("the lions of Mysore"), an idea that Amburgh quickly borrowed. These acts eclipsed equestrianism acts as the central display of circus shows, but truly entered public consciousness in the early twentieth century with cinema. In demonstrating the superiority of human over animal, lion taming served a purpose similar to animal fights of previous centuries.[63] The now iconic lion tamer's chair was possibly first used by American Clyde Beatty (1903â1965).

Cultural depictions

The lion has been an icon used by humanity for thousands of years, appearing in cultures across Europe, Asia, and Africa. Despite incidents of attacks on humans, lions have enjoyed a largely positive depiction in culture as strong but noble creatures. A common depiction is their representation as "king of the jungle" or "king of the beasts"; hence, the lion has been a popular symbol of royalty and stateliness,[65] as well as a symbol of bravery.

Representations of lions date back 32 centuries; the lion-headed ivory carving from the Vogelherd cave in the Swabian Alb in southwestern Germany has been determined to be about 32,000Â years old from the Aurignacian culture.[41] Cave lions are also depicted in the Chauvet Cave, discovered in 1994; this has been dated at 32,000Â years of age,[44] though it may be more recent. Two lions were depicted mating in the Chamber of Felines in 15,000-year-old Paleolithic cave paintings in the Lascaux caves.

Ancient Egypt venerated the lioness (the fierce hunter) as their war deities and among those in the Egyptian pantheon are Bast, Mafdet, Menhit, Pakhet, Sekhmet, Tefnut, and the Sphinx; [65] Among the Egyptian pantheon also are sons of these goddesses, such as, Maahes, and, as attested by Egyptians as a Nubian deity, Dedun.

Careful examination of the lion deities noted in many ancient cultures reveal that many also are lionesses. Admiration for the co-operative hunting strategies of lionesses was evident in very ancient times. Most of the lion gates depict lionesses. The Nemean lion was symbolic in Ancient Greece and Rome, represented as the constellation and zodiac sign Leo, and described in mythology, where its skin was borne by the hero Heracles.[66]

The lion is the biblical emblem of the tribe of Judah and later the Kingdom of Judah. It is contained within Jacob's blessing to his fourth son in the penultimate chapter of the Book of Genesis: "Judah is a lion's whelp; On prey, my son have you grown. He crouches, lies down like a lion, like the king of beastsâwho dare rouse him?" (Genesis 49:9). In the modern state of Israel, the lion remains the symbol of the capital city of Jerusalem, emblazoned on both the flag and coat of arms of the city.

The lion was a prominent symbol in both the Old Babylonian and Neo-Babylonian Empire periods. The classic Babylonian lion motif, found as a statue, carved or painted on walls, is often referred to as the striding lion of Babylon. It is in Babylon that the biblical Daniel is said to have been delivered from the lion's den (Book of Daniel 6).

The lion is featured in several fables of the sixth century B.C.E. Greek storyteller Aesop.[67]

In the Puranic texts of Hinduism, Narasimha ("man-lion"), a half-lion, half-man incarnation or (avatara) of Vishnu, is worshipped by his devotees and saved the child devotee Prahlada from his father, the evil demon king Hiranyakashipu; Vishnu takes the form of half-man/half-lion, in Narasimha, having a human torso and lower body, but with a lion-like face and claws. Narasimha is worshiped as "Lion God."

Singh is an ancient Indian vedic name meaning "lion" (Asiatic lion), dating back over 2000 years to ancient India. It was originally only used by Rajputs a Hindu Kshatriya or military caste in India. After the birth of the Khalsa brotherhood in 1699, the Sikhs also adopted the name "Singh" due to the wishes of Guru Gobind Singh. Along with millions of Hindu Rajputs today, it is also used by over 20 million Sikhs worldwide.

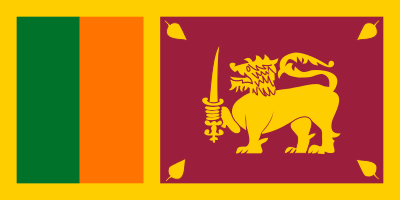

Found famously on numerous flags and coats of arms all across Asia and Europe, the Asiatic lions also stand firm on the National Emblem of India. Farther south on the Indian subcontinent, the Asiatic lion is symbolic for the Sinhalese,Sri Lanka's ethnic majority; the term derived from the Indo-Aryan Sinhala, meaning the "lion people" or "people with lion blood," while a sword wielding lion is the central figure on the national flag of Sri Lanka.

The Asiatic lion is a common motif in Chinese art. They were first used in art during the late Spring and Autumn Period (fifth or sixth century B.C.E.), and became much more popular during the Han Dynasty (206 B.C.E. â 220 C.E.), when imperial guardian lions started to be placed in front of imperial palaces for protection. Because lions have never been native to China, early depictions were somewhat unrealistic; after the introduction of Buddhist art to China in the Tang Dynasty (after the sixth century C.E.), lions were usually depicted without wings, their bodies became thicker and shorter, and their manes became curly. The lion dance is a form of traditional dance in Chinese culture in which performers mimic a lion's movements in a lion costume, often with musical accompaniment from cymbals, drums, and gongs. They are performed at Chinese New Year, the August Moon Festival, and other celebratory occasions for good luck.

The island nation of Singapore (Singapura) derives its name from the Malay words singa (lion) and pura (city), which in turn is from the Tamil-Sanskrit àźàźżàźàŻàź singa à€žà€żà€à€č siáčha and à€Șà„à€° àźȘàŻàź° pura. According to the Malay Annals, this name was given by a fourteenth century Sumatran Malay prince named Sang Nila Utama, who, on alighting the island after a thunderstorm, spotted an auspicious beast on shore that his chief minister identified as a lion (Asiatic lion).

"Aslan" or "Arslan (Ottoman ۧ۱۳ÙŰ§Ù arslÄn and ۧ۔ÙŰ§Ù aáčŁlÄn) is the Turkish and Mongolian word for "lion." It was used as a title by a number of Seljuk and Ottoman rulers, including Alp Arslan and Ali Pasha, and is a Turkic/Iranian name.

"Lion" was the nickname of medieval warrior rulers with a reputation for bravery, such as Richard I of England, known as Richard the Lionheart,[65] Henry the Lion (German: Heinrich der Löwe), Duke of Saxony, and Robert III of Flanders, nicknamed "The Lion of Flanders"âa major Flemish national icon up to the present. Lions are frequently depicted on coats of arms, either as a device on shields themselves, or as supporters. The formal language of heraldry, called blazon, employs French terms to describe the images precisely. Such descriptions specified whether lions or other creatures were "rampant" or "passant," that is whether they were rearing or crouching.[68] The lion is used as a symbol of current sporting teams, from national association football teams such as England, Scotland, and Singapore to clubs such as the Detroit Lions of the National Football League.

Lions continue to feature in modern literature, from the messianic Aslan in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe and following books from the Narnia series written by C. S. Lewis,[69] to the comedic Cowardly Lion in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz.[70] The advent of moving pictures saw the continued presence of lion symbolism; such as Leo the Lion, the mascot for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) studios, which has been in use since the 1920s; the Kenyan animal Elsa in the movie Born Free, and and the 1994 Disney animated feature film The Lion King.

Notes

- â D. E. Wilson, and D. M. Reeder (eds.), Mammal Species of the World, 3rd ed. (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005, ISBN 0801882214).

- â 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 H. Bauer, K. Nowell, and C. Packer, Panthera leo, in The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved May 12, 2023.

- â 3.0 3.1 V. G. Heptner and A. A. Sludskii, Mammals of the Soviet Union, volume II, Part 2 (Leiden:Brill, 1992, ISBN 9004088768).

- â 4.0 4.1 Honolulu Zoo, "Lion," Honolulu Zoo. Retrieved May 12, 2023.

- â 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 5.12 5.13 5.14 5.15 5.16 5.17 5.18 5.19 5.20 5.21 5.22 George B. Schaller, The Serengeti Lion: A Study of Predator-Prey Relations (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1972, ISBN 0226736393).

- â Chris McBride, The White Lions of Timbavati (Johannesburg: E. Stanton, 1977, ISBN 0949997323).

- â 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Ronald M. Nowak, Walker's Mammals of the World (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999, ISBN 0801857899).

- â 8.0 8.1 8.2 Kristin Nowell and Peter Jackson (eds.), Wild Cats: Status Survey and Conservation Action (Gland, Switzerland: IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group, 1996, ISBN 2831700450).

- â 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 Jonathan Scott and Angela Scott, Big Cat Diary: Lion (HarperCollins UK, 2006, ISBN 0007211791).

- â 10.0 10.1 Gerald Wood, The Guinness Book of Animal Facts and Feats (Sterling Pub Co., 1983, ISBN 9780851122359).

- â James Randerson, Lionesses go for dark, flowing manes New Scientist August 22, 2002. Retrieved May 12, 2023.

- â 12.0 12.1 P. M. West, and C. Parker, "Sexual selection, temperature, and the lion's mane," Science 297(2002)(issue 5585): 1339â1343. Retrieved May 12, 2023.

- â 13.0 13.1 13.2 R. Barnett, N. Yamaguchi, I. Barnes, and A. Cooper, "Lost populations and preserving genetic diversity in the lion Panthera leo: Implications for its ex situ conservation," Conservation Genetics 7(4) (2006): 507â514.

- â Vivek Menon, A Field Guide to Indian Mammals (Delhi: Dorling Kindersley India, 2003, ISBN 0143029983).

- â 15.0 15.1 Wighart von Koenigswald, Lebendige Eiszeit: Klima und Tierwelt im Wandel (Stuttgart: Theiss, 2002, ISBN 3806217343).

- â 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 Catherine Bell (ed)., Encyclopedia of the World's Zoos, Volume 2 (Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn, 2001, ISBN 1579581749).

- â 17.0 17.1 C. R. Harington, "Pleistocene remains of the lion-like cat (Panthera atrox) from the Yukon Territory and northern Alaska," Canadian Journal Earth Sciences 6(1969)(issue 5): 1277â1288.

- â Judith A. Rudnai, The Social Life of the Lion (Wallingford, PA: Washington Square East, 1973, ISBN 0852000537).

- â Asiatic Lion Information Centre, "The Gir," Wildlife Conservation Trust (2006).

- â R. Heinsohn and C. Packer, "Complex cooperative strategies in group-territorial African lions," Science 269(5228) (1995): 1260â1262.

- â V. Morell, "Cowardly lions confound cooperation theory," Science 269(5228) (1995): 1216â1217.

- â G. C. Jahn, "Lioness Leadership," Science 271(5253) (1996): 1215.

- â Christine Denis-Huot and Michel Denis-Huot, The Art of Being a Lion (New York: Friedman/Fairfax, 2002, ISBN 158663707X).

- â M. W. Hayward, and G. Kerley, "Prey preferences of the lion (Panthera leo)," Journal of Zoology 267(3) (2005): 309â322.

- â U. de V. Pienaar, "Predator-prey relationships amongst the larger mammals of the Kruger National Park," Koedoe 12(1969): 108.

- â Iain Douglas-Hamilton and Oria Douglas-Hamilton, Among the Elephants (New York: Viking Press, 1975, ISBN 0670122084).

- â D. Whitworth, "King of the jungle defies nature with new quarry," The Australian October 9, 2006.

- â C. A. W. Guggisberg, Simba: The Life of the Lion (Cape Town: Howard Timmins, 1961).

- â P. E. Stander, "Cooperative hunting in lions: The role of the individual," Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 29(6) (1992): 445â454.

- â G. L. Smuts, Lion (Intl Specialized Book Services, 1983, ISBN 0869541226).

- â Virginia Hayssen, Ari Tienhoven, and Ans Tienhoven, Asdell's Patterns of Mammalian Reproduction: A Compendium of Species-Specific Data (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University, 1993, ISBN 9780801417535).

- â 32.0 32.1 C. Packer, and A. E. Pusey, "Adaptations of female lions to infanticide by incoming males," American Naturalist 121(5) (1983): 716â728.

- â David W. Macdonald (ed.), The Encyclopedia of Mammals (New York: Facts on File, 1984, ISBN 0871968711).

- â Desmond Morris (ed.), Primate Ethology (Chicago: Aldine, 1967, ISBN 978-1122288712).

- â S. O'Brien, D. Wildt, and M. Bush, "The cheetah in genetic peril," Scientific American 254 (1986): 68â76.

- â C. A. W. Guggisberg, Crocodiles: Their Natural History, Folklore, and Conservation (Newton Abbot: David & Charles, 1972, ISBN 0715352725).

- â L. Werdelin, and M. E. Lewis, "Plio-Pleistocene Carnivora of eastern Africa: Species richness and turnover patterns," Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 144(2) (2005): 121â144.

- â L. Yu and Z. Ya-ping, "Phylogenetic studies of pantherine cats (Felidae) based on multiple genes, with novel application of nuclear ÎČ-fibrinogen intron 7 to carnivores," Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 35(2) (2005): 483â495.

- â N. Yamaguchi, A. Cooper, L. Werdelin, and D. W. Macdonald, "Evolution of the mane and groupâliving in the lion (Panthera leo): A review," Journal of Zoology 263(4) (2004): 329â342. Retrieved May 12, 2023.

- â Alan Turner, The Big cats and Their Fossil Relatives: An Illustrated Guide to Their Evolution and Natural History (New York: Columbia University Press, 1997, ISBN 0231102291).

- â 41.0 41.1 41.2 41.3 41.4 41.5 41.6 J. Burger, W. Rosendahl, O. Loreille, et al., "Molecular phylogeny of the extinct cave lion Panthera leo spelaea," Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 30(3) (2004): 841â849.

- â R. Barnett, N. Yamaguchi, I. Barnes, and A. Cooper, "The origin, current diversity and future conservation of the modern lion (Panthera leo)," Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 273(1598) (2006): 2119â2125.

- â Paul S. Martin and Richard G. Klein (eds.), Quaternary Extinctions (Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press, 1984, ISBN 0816511004).

- â 44.0 44.1 C. Packer and J. Clottes, "When lions ruled France," Natural History November (2000): 52â57.

- â K. Manamendra-Arachchi, R. Pethiyagoda, R. Dissanayake, and M. Meegaskumbura, "A second extinct big cat from the late Quaternary of Sri Lanka," The Raffles Bulletin of Zoology Supplement 12(2005): 423â434.

- â Karl P.N. Shuker, Mystery Cats of the World (Robert Hale, 1989, ISBN 0709037066).

- â C. A. W. Guggisberg, Wild Cats of the World (New York: Taplinger Publishing, 1975, ISBN 0800883241).

- â Scott Markel, and Darryl LeĂłn, Sequence Analysis in a Nutshell: A Guide to Common Tools and Databases (Sebastopol, CA: O'Reily, 2003, ISBN 059600494X).

- â H. Doi and B. Reynolds, The Story of Leopons (New York: Putnam, 1967).

- â African Wildlife Foundation, "Lion,", African Wildlife Foundation. Retrieved May 12, 2023.

- â V. K. Saberwal, J. P. Gibbs, R. Chellam, and A. J. T. Johnsingh, "Lion-human conflict in the Gir Forest, India," Conservation Biology 8(2) (1994): 501â507.

- â A. J. T. Johnsingh, "WII in the field: Is Kuno Wildlife Sanctuary ready to play second home to Asiatic lions?" Wildlife Institute of India Newsletter 11(4) (2004).

- â W. Hosek, "The man-eater of Mfuwe," Field Museum of Natural History.

- â D. Dickinson, "Toothache 'made lion eat humans'" BBC News October 19, 2004. Retrieved May 12, 2023.

- â B. D. Patterson, E. J. Neiburger, and S. M. Kasiki, "Tooth breakage and dental disease as causes of carnivore-human conflicts," Journal of Mammalogy 84(1) (2003): 190â196. Retrieved May 12, 2023.

- â J. C. Kerbis Peterhans and T. P. Gnoske, "The science of man-eating," Journal of East African Natural History 90(1&2) (2001): 1â40.

- â 57.0 57.1 C. Packer, D. Ikanda, B. Kissui, and H. Kushnir, "Conservation biology: Lion attacks on humans in Tanzania," Nature 436(7053) (2005): 927â928. Retrieved May 12, 2023.

- â Robert Frump, The Man-Eaters of Eden: Life and Death in Kruger National Park (Lyons Press, 2006, ISBN 1592288928).

- â G. G. Rushby, No More the Tusker (London: W. H. Allen, 1965).

- â 60.0 60.1 60.2 Catherine de Courcy, The Zoo Story (Ringwood, Victoria: Penguin Books, 1995, ISBN 0140239197).

- â Vincent A. Smith, The Early History of India (CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2014, (original 1914), ISBN 978-1500103903).

- â Thomas Wiedemann, Emperors and Gladiators (Routledge, 1995, ISBN 0415121647).

- â 63.0 63.1 63.2 63.3 63.4 63.5 Eric Baratay, and Elisabeth Hardouin-Fugier, Zoo: A History of Zoological Gardens in the West (London: Reaktion Books, 2002, ISBN 1861891113).

- â 64.0 64.1 64.2 64.3 64.4 Wilfrid Blunt, The Ark in the Park: The Zoo in the Nineteenth Century (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1975, ISBN 0241893313).

- â 65.0 65.1 65.2 Jana Garai, The Book of Symbols (Lorrimer, 1973, ISBN 0856470244).

- â Robert Graves, Greek Myths (London: Penguin, 1995, ISBN 0140010262).

- â Aesop, Aesop's Fables (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002, ISBN 0192840509).

- â University of Notre Dame, Heraldic Dictionary: Beasts University of Notre Dame. Retrieved May 12, 2023.

- â C. S. Lewis, The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (HarperCollins, 1950, ISBN 0060234814).

- â L. Frank Baum, The Annotated Wizard of Oz (New York: C. N. Potter, 1973, ISBN 0517500868).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Aesop, Aesop's Fables. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002. ISBN 0192840509

- Baratay, Eric, and Elisabeth Hardouin-Fugier. Zoo: A History of Zoological Gardens in the West. London: Reaktion Books, 2002. ISBN 1861891113

- Baum, L. Frank. The Annotated Wizard of Oz. New York: C. N. Potter, 1973. ISBN 0517500868

- Bell, Catherine (ed). Encyclopedia of the World's Zoos, Volume 2. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn, 2001. ISBN 1579581749

- Blunt, Wilfrid. The Ark in the Park: The Zoo in the Nineteenth Century. London: Hamish Hamilton, 1975. ISBN 0241893313

- de Courcy, Catherine. The Zoo Story. Ringwood, Victoria: Penguin Books, 1995. ISBN 0140239197

- Denis-Huot, Christine, and Michel Denis-Huot. The Art of Being a Lion. New York: Friedman/Fairfax, 2002. ISBN 158663707X

- Doi, H., and B. Reynolds. The Story of Leopons. New York: Putnam, 1967.

- Douglas-Hamilton, Iain, and Oria Douglas-Hamilton. Among the Elephants. New York: Viking Press, 1975. ISBN 0670122084

- Frump, Robert. The Man-Eaters of Eden: Life and Death in Kruger National Park. Lyons Press, 2006. ISBN 1592288928

- Garai, Jana. The Book of Symbols. Lorrimer, 1973. ISBN 0856470244

- Graves, Robert. Greek Myths. London: Penguin, 1995. ISBN 0140010262

- Guggisberg, C. A. W. Simba: The Life of the Lion. Cape Town: Howard Timmins, 1961. ASIN B0007DLQ7G

- Guggisberg, C. A. W. Crocodiles: Their Natural History, Folklore, and Conservation. Newton Abbot: David & Charles, 1972. ISBN 0715352725

- Guggisberg, C. A. W. Wild Cats of the World. New York: Taplinger Publishing, 1975. ISBN 0800883241

- Hayssen, Virginia, Ari Tienhoven, and Ans Tienhoven. Asdell's Patterns of Mammalian Reproduction: A Compendium of Species-Specific Data. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University, 1993. ISBN 9780801417535

- Heptner, V. G., and A. A. Sludskii. Mammals of the Soviet Union, volume II. Leiden:Brill, 1992. ISBN 9004088768

- Lewis, C. S. The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. HarperCollins, 1950. ISBN 0060234814

- Macdonald, David W. (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Mammals. New York: Facts on File, 1984. ISBN 0871968711

- Markel, Scott, and Darryl LeĂłn. Sequence Analysis in a Nutshell: A Guide to Common Tools and Databases. Sebastopol, CA: O'Reily, 2003. ISBN 059600494X

- Martin, Paul S., and Richard G. Klein (eds.). Quaternary Extinctions. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press, 1984. ISBN 0816511004

- McBride, Chris. The White Lions of Timbavati. (Johannesburg: E. Stanton, 1977. ISBN 0949997323

- Menon, Vivek. A Field Guide to Indian Mammals. Delhi: Dorling Kindersley India, 2003. ISBN 0143029983

- Morris, Desmond (ed.). Primate Ethology. Chicago: Aldine, 1967. ISBN 978-1122288712

- Nowak, Ronald M. Walker's Mammals of the World. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999. ISBN 0801857899

- Nowell, Kristin, and Peter Jackson (eds.). Wild Cats: Status Survey and Conservation Action (Gland, Switzerland: IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group, 1996. ISBN 2831700450

- Rudnai, Judith A. The Social Life of the Lion. Wallingford, PA: Washington Square East, 1973. ISBN 0852000537

- Rushby, G. G. No More the Tusker. London: W. H. Allen, 1965. ASIN B001O3CUS2

- Schaller, George B. The Serengeti Lion: A Study of Predator-Prey Relations. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1972. ISBN 0226736393

- Scott, Jonathan, and Angela Scott. Big Cat Diary: Lion. HarperCollins UK, 2006. ISBN 0007211791

- Shuker, Karl P.N. Mystery Cats of the World. Robert Hale, 1989. ISBN 0709037066

- Smith, Vincent A. The Early History of India. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2014, (original 1914). ISBN 978-1500103903

- Smuts, G. L. Lion. Intl Specialized Book Services, 1983. ISBN 0869541226

- Turner, Alan. The Big cats and Their Fossil Relatives: An Illustrated Guide to Their Evolution and Natural History. New York: Columbia University Press, 1997. ISBN 0231102291

- von Koenigswald, Wighart. Lebendige Eiszeit: Klima und Tierwelt im Wandel. Stuttgart: Theiss, 2002. ISBN 3806217343

- Wiedemann, Thomas. Emperors and Gladiators. Routledge, 1995. ISBN 0415121647

- Wilson, Don E. and DeeAnn M. Reeder (eds.). Mammal Species of the World. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005. ISBN 0801882214

- Wood, Gerald. The Guinness Book of Animal Facts and Feats. Sterling Pub Co., 1983. ISBN 9780851122359

| ||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.