Ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt as a general historical term broadly refers to the civilization of the Nile Valley between the First Cataract and the mouths of the Nile Delta, from circa 3300 B.C.E. until the conquest of Alexander the Great in 332 B.C.E.. As a civilization based on irrigation, it is the quintessential example of a hydraulic empire. It was one of the oldest, and the longest, human civilizations. Egypt has been a great source of inspiration and of interest for Europeans especially, who regard it as of almost mysterious significance. Egypt served as a conduit between Europe and Africa.

Egyptian civilization had a bias towards unity, rather than towards confrontation. Ancient Egyptian contributions to knowledge in the areas of mathematics, medicine, and astronomy continue to inform modern thought. Egyptian hieroglyphs underlay our alphabet. Through the Alexandria Library and such scholars as the mathematician Claudius Ptolemaeus and the Hellenistic-Jewish scholar Philo, this reputation continued. Through the Ptolemies, Hellenistic and Egyptian ideas came together and Egyptian religion, especially the cult of Isis, became popular throughout the Greco-Roman world. The Roman Emperors, after Cleopatra the last Ptolemy, claimed the ancient title and honor of the Pharaohs.

Many Christians see deep significance that Jesus, according to tradition, spent time in Egypt. Indeed, early Christianity in Egypt saw much theological thought and several alternatives to what emerged as mainstream Christianity emerged, some stressing the feminine role while the Nag Hammadi collection of formerly lost texts, including the Gospel of Thomas, has significantly supplemented modern Bible scholarship. The Coptic church of Egypt is one of the world's oldest.

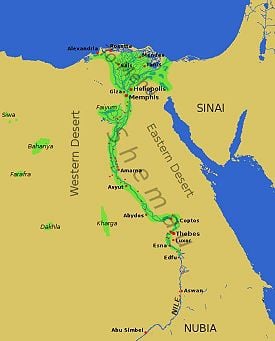

Geography

Most of the geography of Egypt is in North Africa, although the Sinai Peninsula is in Southwest Asia. The country has shorelines on the Mediterranean Sea and the Red Sea; it borders Libya to the west, Sudan to the south, and the Gaza Strip, Palestine and Israel to the east. Ancient Egypt was divided into two kingdoms, known as Upper and Lower Egypt. Somewhat counter-intuitively, Upper Egypt was in the south and Lower Egypt in the north, named according to the flow of the Nile river. The Nile flows northward from a southerly point to the Mediterranean. The river, around which much of the population of the country clusters, has been the lifeline for Egyptian culture since the Stone Age and Naqada cultures.

Two Kingdoms formed Kemet ("the black"), the name for the dark soil deposited by the Nile floodwaters. The desert was called Deshret ("the red") Herodotus wrote, "Egypt is a land of black soil.... We know that Libya is a redder earth" (Histories, 2:12). However Champollion the Younger (who deciphered the Rossetta stone) wrote in Expressions et Termes Particuliers (‚ÄúExpression of Particular Terms‚ÄĚ) Kemet did not actually refer to the soil but to a negroid population in the sense of a "Black Nation."

Ancient Egyptian peoples

Neolithic Egypt was probably inhabited by black African (Nilotic) peoples (as demonstrated by Saharan petroglyphs throughout the region). Following the desiccation of the Sahara, most black Africans migrated south into East Africa and West Africa. The Aterian culture that developed here was one of the most advanced Paleolithic societies. In the Mesolithic the Caspian culture dominated the region with Neolithic farmers becoming predominant by 6000 B.C.E.. The ancient Egyptians spoke an Afro-Asiatic language, related to Chadic, Berber, and Semitic languages, and recorded their origin as the Land of Punt.

Herodotus once wrote, "the Colchians are Egyptians ... on the fact that they are black-skinned and have wooly hair" (Histories Book 2:104). A genetic study links the maternal lineage of a traditional population from Upper Egypt to Eastern Africa.[1] A separate study that further narrows the genetic lineage to Northeast Africa[2] reveals also that ‚Äúmodern day‚ÄĚ Egyptians "reflect a mixture of European, Middle Eastern, and African"). The racial classification of Ancient Egypt has come to play a role in the Afrocentrism debate in the United States, where Egypt's legacy becomes a prize over which Africans and Europeans contest ownership.

History

The ancient Egyptians themselves traced their origin to a land they called Land of Punt, or "Ta Nteru" ("Land of the Gods"). Once commonly thought to be located on what is today the Somali coast, Punt now is thought to have been in either southern Sudan or Eritrea. The history of ancient Egypt proper starts with Egypt as a unified state, which occurred sometime around 3000 B.C.E., though archaeological evidence indicates a developed Egyptian society may have existed for a much longer period.

Along the Nile in the tenth millennium B.C.E., a grain-grinding culture using the earliest type of sickle blades had been replaced by another culture of hunters, fishers, and gathering peoples using stone tools. Evidence also indicates human habitation in the southwestern corner of Egypt, near the Sudan border, before 8000 B.C.E. Climate changes and/or overgrazing around 8000 B.C.E. began to desiccate the pastoral lands of Egypt, eventually forming the Sahara (c. 2500 B.C.E.), and early tribes naturally migrated to the Nile river where they developed a settled agricultural economy and more centralized society. There is evidence of pastoralism and cultivation of cereals in the East Sahara in the seventh millennium B.C.E.. By 6000 B.C.E., ancient Egyptians in the southwestern corner of Egypt were herding cattle and constructing large buildings. Mortar was in use by 4000 B.C.E.. The Predynastic Period continues through this time, variously held to begin with the Naqada culture. Some authorities however begin the Predynastic Period earlier, in the Lower Paleolithic age.

Egypt unified as a single state circa 3000 B.C.E.. Egyptian chronology involves assigning beginnings and endings to various dynasties from around this time. Manetho, who was a priest during the reigns of Ptolemy I and Ptolemy II (30th dynasty), divided the dynasties into 30; the 31st (Persian) and 32nd dynasties (the Ptolemies) were added after his death. Sometimes, though, he placed a Pharaoh in one dynasty who may properly have been considered founder of the next one, thus the beginning and ending of dynasties seems arbitrary. Even within a single work, archeologists may offer several possible dates or even several whole chronologies as possibilities. Consequently, there may be discrepancies between dates shown here and in articles on particular rulers. Often there are also several possible spellings of the names.

The Pharaohs stretch from before 3000 B.C.E. to around 30 C.E. and continued through the Roman Emperors, who claimed the title.

Dynasties

- Early Dynastic Period of Egypt (1st - 2nd Dynasties; until c. 27th century B.C.E.)

- Old Kingdom (3rd - 6th Dynasties; 27th - 22nd centuries B.C.E.)

- First Intermediate Period (7th - 11th Dynasties)

- Middle Kingdom of Egypt (11th - 14th Dynasties; 20th - 17th centuries B.C.E.)

- Second Intermediate Period (14th - 17th Dynasties)

- Hyksos (15th - 16th Dynasties)

- New Kingdom of Egypt (18th - 20th Dynasties; 16th - 11th centuries B.C.E.)

- Third Intermediate Period (21st - 25th Dynasties; 11th - 7th centuries B.C.E.)

- Late Period of Ancient Egypt (26th - 32nd Dynasties; 7th century B.C.E. - 30 C.E.).

Significant Events and Rulers

Around about 3100 B.C.E., the two kingdoms of Upper and Lower Egypt were united and the first dynasty was established. This is largely credited to Menes, or Aha of Memphis (who founded the city), who may also have authored the founding myth or story of Egypt. He may have been the first Pharaoh to be identified with Horus, the Falcon-god associated with the sky. During the fourth dynasty, founded by Snefru, the Great Pyramid at Giza was built by Khufu, known to the Greeks as Cheops, who is said to have reigned for 50 or 60 years.

During the sixth dynasty (2345-2181 B.C.E.), possibly due to a fluctuation in the flow of the Nile that resulted in periods of famine, central authority was weakened and the two kingdoms were divided. Mentuhopet of Thebes (c. 2040 B.C.E.) established the Middle Kingdom when he reunified the two Egypts. During this period, Amun the God of Thebes became identified with the Sun God, Re, and to be seen as the chief God and as sponsor of the Pharaohs. This was a period of vigorous trade with Syria, Palestine, and Nubia. Several important forts were built near the second Cataract of the Nile. Art and literature flourished.

During the next period, known as the Second Intermediate Period (1720-1550 B.C.E.), a tribe known as the Hyksos, from the East, gained power over parts of Egypt and real power devolved from the center to local rulers, again compromising the unity of the two Egypts.

Circa 1550 B.C.E. the rulers of Thebes once again re-unified Egypt, establishing the New Kingdom. They acquired an empire stretching as far as the Euphrates in the North and into Nubia in the South. Huge building projects, mainly temples and funerary monuments, characterized this period. The cult of Amun-Re dominated, with the High Priest exercising considerable power, except for the brief intermission when Akhenaten declared that the God, Aten, was the sole God who could not be visually represented. One of the most well known Pharoahs, Rameses II (1279-1213 B.C.E.), dates from this period. He is popularly associated with the Pharaoh of the time of Moses who engaged in war with the Hittites. His courage during the battle of Kadesh against the Hittites made him into a living legend. The many Temples commissioned during his reign include Abu Simbel, the Colossus of Ramesses at Memphis and Nefretari's tomb in the Valley of the Queens. Queen Nefretari is depicted as Rameses' equal. Renowned for her beauty, she may also have exercised power alongside her husband, since Queens were traditionally portrayed as smaller than their consorts. During the reign of Rameses III, known as the last of the great pharaohs, Egypt's security was constantly threatened from the east by the Lybians. The external territories were lost and by the start of the twentieth dynasty, the two Egypts were divided once again.

In 341 B.C.E., the last native dynasty (the thirtieth) fell to the Persians, who controlled Egypt until 332 B.C.E. when Alexander the Great conquered the territory. In 323, Ptolemy, one of Alexander's Generals, became ruler and founded the Ptolemaic dynasty that lasted until its conquest by Rome after the death of Cleopatra in 30 B.C.E. The Ptolemies were patrons of learning, and Egypt's already well established tradition as a center of knowledge continued under their sponsorship. Many Jews living in Egypt prospered, and temples were built there on Elephantine island in the Aswan delta (as early as the fifth century B.C.E.) and later, in 160 B.C.E., at Heliopolis (Leontopolis.) One of the most important Jewish thinkers, Philo, lived in Alexandria‚ÄĒwhich later produced some leading Christian scholars. The Roman emperors continued to claim the title and honors of the Pharaohs.

Government

Subnational administrative divisions of Upper and Lower Egypt were known as Nomes. The pharaoh was the ruler of these two kingdoms and headed the ancient Egyptian state structure. The pharaoh served as monarch, spiritual leader and commander-in-chief of both the army and navy. The pharaoh was believed to be divine, a connection between men and gods. Below him in the government, were the viziers (one for Upper Egypt and one for Lower Egypt) and various officials. Under him on the religious side were the high priest and various other priests. Generally, the position was handed down from father to eldest son but it was through the female that power was actually inherited, so it was marriage to the king's eldest daughter that sealed succession. Occasionally a woman assumed power and quite often Queens were powerful figures in their own right. Governance was closely associated with the duty of ruling with justice and of preventing chaos by maintaining harmony and balance. The priests especially the High Priest of Amen-Ra exercised considerable power partly because of the wealth of the cultus and also because they had the final say in determining the succession. Akhenaten's break with the traditional cultus followed a power struggle between Pharoah and the priesthood.[3]

Language

The ancient Egyptians spoke an Afro-Asiatic language related to Chadic, Berber and Semitic languages. Records of the ancient Egyptian language have been dated to about 32nd century B.C.E. Scholars group the Egyptian language into six major chronological divisions:

- Archaic Egyptian (before 2600 B.C.E.)

- Old Egyptian (2600‚Äď2000 B.C.E.)

- Middle Egyptian (2000‚Äď1300 B.C.E.)

- Late Egyptian (1300‚Äď700 B.C.E.)

- Demotic Egyptian (7th century B.C.E.‚Äď4th century C.E.)

- Coptic (3rd‚Äď12th century C.E.)

Writing

Egyptologists refer to Egyptian writing as Egyptian hieroglyphs, together with the cuneiform script of Mesopotamia ranking as the world's oldest writing system. The hieroglyphic script was partly syllabic, partly ideographic. Hieratic is a cursive form of Egyptian hieroglyphs first used during the First Dynasty (c. 2925 B.C.E. - c. 2775 B.C.E.). The term Demotic in the context of Egypt, that is, "indigenous" from a Hellenistic point of view, came to refer to both the script and the language that followed the Late Ancient Egyptian stage from the Nubian 25th dynasty until its marginalization by the Greek Koine in the early centuries C.E.. After the conquest of Umar ibn al-Khattab, the Coptic language survived into the Middle Ages as the liturgical language of the Christian minority.

The hieroglyphic script finally fell out of use around the fourth century, and began to be rediscovered from the fifteenth century.

The oldest known alphabet (abjad) was also created in ancient Egypt, as a derivation from syllabic hieroglyphs.

Literature

- c. 26th century B.C.E. - Westcar Papyrus

- c.19th century B.C.E. The Story of Sinuhe

- c. 1800 B.C.E. - Ipuwer papyrus

- c. 1800 B.C.E. - Papyrus Harris I

- c. 11th century B.C.E. - Story of Wenamun

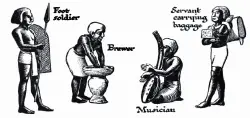

Culture

The religious nature of ancient Egyptian civilization influenced its contribution to the arts of the ancient world. Many of the great works of ancient Egypt depict gods, goddesses, and pharaohs, who were also considered divine. Ancient Egyptian art in general is characterized by the idea of order, which was the dominant motif of Egyptian religion.

The excavation of the workers village of Deir el-Madinah has resulted in one of the most thoroughly documented accounts of community life in the ancient world that spans almost four hundred years. There is no comparable site in which the organization, social interactions, working and living conditions of a community can be studied in such detail.[4]

Most ancient Egyptians were farmers tied to the land. Their dwellings were restricted to immediate family members, and were constructed of mud-brick designed to remain cool in the heat of the day. Each home had a kitchen with an open roof, which contained a grindstone for milling flour and a small oven for baking bread. Walls were painted white and could be covered with dyed linen wall hangings. Floors were covered with reed mats, while wooden stools, beds raised from the floor and individual tables comprised the furniture.[5]

The ancient Egyptians placed a great value on hygiene and appearance. Most bathed in the Nile and used a pasty soap made from animal fat and chalk. Men shaved their entire bodies for cleanliness, and aromatic perfumes and ointments covered bad odors and soothed skin. Clothing was made from simple linen sheets that were bleached white, and both men and women of the upper classes wore wigs, jewelry, and cosmetics. Children went without clothing until maturity, at about age 12, and at this age males were circumcised and had their heads shaved. Mothers were responsible for taking care of the children, while the father provided the family's income.[5]

Music and dance were popular entertainments for those who could afford them. Early instruments included flutes and harps, while instruments similar to trumpets, oboes, and pipes developed later and became popular. In the New Kingdom, the Egyptians played on bells, cymbals, tambourines, and drums as well as imported lutes and lyres from Asia.[6] The sistrum was a rattle-like musical instrument that was especially important in religious ceremonies.

The ancient Egyptians enjoyed a variety of leisure activities, including games. Senet, a board game where pieces moved according to random chance, was particularly popular from the earliest times; another similar game was mehen, which had a circular gaming board. Juggling and ball games were popular with children, and wrestling is also documented in a tomb at Beni Hasan.[5] The wealthy members of ancient Egyptian society enjoyed hunting and boating as well.

Egyptian cuisine remained remarkably stable over time, as evidenced by analysis of the hair of ancient Egyptian mummies from the Late Middle Kingdom.[7] In fact, the cuisine of modern Egypt retains some striking similarities to the cuisine of the ancients. The staple diet consisted of bread and beer, supplemented with vegetables such as onions and garlic, and fruit such as dates and figs. Wine and meat were enjoyed by all on feast days while the upper classes indulged on a more regular basis. Fish, meat, and fowl could be salted or dried, and could be cooked in stews or roasted on a grill.[5] However, mummies from circa 3200 B.C.E. show signs of severe anemia and hemolitic disorders.[8] Traces of cocaine, hashish and nicotine have also been found in the skin and hair of Egyptian mummies.[9]

The Egyptians believed that a balanced relationship between people and animals was an essential element of the cosmic order; thus humans, animals and plants were believed to be members of a single whole.[10] Animals, both domesticated and wild, were therefore a critical source of spirituality, companionship, and sustenance to the ancient Egyptians. Cattle were the most important livestock; the administration collected taxes on livestock in regular censuses, and the size of a herd reflected the prestige and importance of the estate or temple that owned them. In addition to cattle, the ancient Egyptians kept sheep, goats, and pigs. Poultry such as ducks, geese, and pigeons were captured in nets and bred on farms, where they were force-fed with dough to fatten them.[5] The Nile provided a plentiful source of fish. Bees were also domesticated from at least the Old Kingdom, and they provided both honey and wax.[11]

The ancient Egyptians used donkeys and oxen as beasts of burden, and they were responsible for plowing the fields and trampling seed into the soil. The slaughter of a fattened ox was also a central part of an offering ritual.[5] Horses were introduced by the Hyksos in the Second Intermediate Period, and the camel, although known from the New Kingdom, was not used as a beast of burden until the Late Period. There is also evidence to suggest that elephants were briefly utilized in the Late Period, but largely abandoned due to lack of grazing land.[5]

Dogs, cats and monkeys were common family pets, while more exotic pets imported from the heart of Africa, such as lions, were reserved for royalty. Herodotus observed that the Egyptians were the only people to keep their animals with them in their houses.[10] During the Predynastic and Late periods, the worship of the gods in their animal form was extremely popular, such as the cat goddess Bastet and the ibis god Thoth, and these animals were bred in large numbers on farms for the purpose of ritual sacrifice.[12]

Religion

Egyptian religion permeated every aspect of life. It dominated life to such an extent that almost all the monuments and buildings that have survived the century, including huge constructions that required thousands of laborers or slaves and many years to build, are religious rather secular. The dominant concern of religion was maintenance of the rhythm of life, symbolized by the Nile, and with preventing order from degenerating into chaos. The term maat was used to describe the essential order of the universe, and the Pharaoh's duty was to uphold this by the rule of law and by ensuring that justice was done. Egyptians believed profoundly in an afterlife, and maat was so important that it represented an eternal principle before which even the Gods deferred.

Around about 3000 B.C.E., Menes established Memphis as the new capital of both Egypts and elevated what had been the Memphis-myth as the dominant myth. However, many local myths of creation and of origins also continued to exist alongside this dominant one without creating tension. In the Memphis-myth, a supreme entity called Ptah created everything, or, rather, everything that is, ideas, truth, justice, beauty, people, Gods, emanated from Ptah originating as "thoughts" in Ptah's mind. Egypt's unity was central to this myth. Other creation myths depicted creation as proceeding from out or primordial chaos, or from a primordial slime, which had eight elements, namely matter and space, darkness and obscurity, the illimitable and the boundless and the hidden and concealed). The annual flooding by the Nile, leading to new life, may lie behind this mythology.

The gods Seth (of winds and storms) and Horus (falcon sky-god) struggled for control of Egypt, mediated by Geb (or Ptah). Initially, each ruled one Egypt but the bias towards unity resulted in Geb ceding both Egypts to Horus, the elder of the two. Other myths have a group of Gods create earth, with another group acting as mediators between the Gods and humans. The latter group includes Osiris, Isis, Seth, and Nepthys. Osiris was the god of the dead; Isis was the Mother-God; Nepthys was the female counterpart of Seth. Horus assumed importance as the child of Isis and Osiris. Osiris is said to have taught Egyptians agriculture and religion, while Isis restored Osiris to life when his jealous brother, Seth, murdered him. The cult of Isis spread throughout the Roman Empire. It involved secret knowledge, secret texts, visions of Isis and of Osiris, and the concept of salvation as a return for personal dedication to the Goddess. Horus is credited with battling against Seth to vindicate his father, and with winning control of Egypt. Thus, Horus becomes prince of the Gods and sponsor of the Kings, who were regarded as his human forms. Some 2,000 deities made up the pantheon. Local variations of myth and local myths appear to have co-existed side by side with the master or dominant narrative without conflict.

Much effort and wealth was invested in building funerary monuments and tombs for the rulers. It was believed that humans consist of three elements, the ka, the ba, and the akh. The ka remained in the tomb and can be described as the "genius" of the individual. The ba resembles a soul, while the akh acquires a supernatural power after death, remaining dormant until then. After death, all are judged according to the principle of maat, weighed by the jackal-God, Annubis, against the heart of the deceased. If the heart is heavier, the deceased will be consigned to oblivion. If maat is heavier, Osiris receives the deceased into his realm. This was the "abode of the blessed," a locality believed to be literally in the heavens where the Gods dwelt. Thoth, the ibis-headed god of wisdom, records all. Many of the legends and practices are described in the Book of the Dead.[13]Temples were earthly dwelling places for the Gods, and functioned as meeting-points between heaven and earth, or as cosmic centers. The priests served the Gods but also performed social functions including teaching, conducting religious rites and offering advise. Death was regarded as transitory.

The divine and the human were intricately linked. Gods were at one and the same time divine and human. Their depiction as animals was another indication of the divinity of the earth and of nature itself; the divine was part and parcel of creation. The gods were concerned with human problems, not detached and distant. Anyone who killed an animal faced death. Cats were especially revered, and were even mummified. The Nile, from which Egypt drew its water and on which it depended for its fertility, was itself sacred. The concern with fertility informed what has been described as a healthy attitude towards sex, which was not regarded as tainted with guilt but as an enjoyable activity, although within the parameters of marriage. Adultery was illegal. The Gods are depicted as enjoying sex and as sometimes breaking the rules. Ra is said to have masturbated his children, Shu and Tefnut, into existence. Incest was also illegal with the exception of the royal family, where brother-sister marriage was necessary for the succession. Believing that life after death would be more or less a continuation of life on earth, sexual activity would not cease after death. Thus, some Egyptian men attached false penises to their mummies while Egyptian women added artificial nipples.[14]

Mummification

Mummies are probably most popularly associated with Egyptian religion. Mummification was religious and accompanied by ritual prayers. Internal organs were removed and separately preserved. The idea behind mummification was probably to maintain the link between the ka and the other two elements, which could be sustained in the afterlife by the preservation of the body in this world. [15] Cats and dogs were also mummified, evidence of the important place that pets occupied in Egyptian life.

Scientific achievements

The art and science of engineering was present in Egypt, such as accurately determining the position of points and the distances between them (known as surveying). These skills were used to outline pyramid bases. The Egyptian pyramids took the geometric shape formed from a polygonal base and a point, called the apex, by triangular faces. Cement was first invented by the Egyptians. The Al Fayyum water works was one of the main agricultural breadbaskets of the ancient world. There is evidence of ancient Egyptian pharaohs of the dynasty using the natural lake of the Fayyum as a reservoir to store surpluses of water for use during the dry seasons. From the time of the first dynasty or before, the Egyptians mined turquoise in the Sinai Peninsula.

The earliest evidence (c. 1600 B.C.E.) of traditional empiricism is credited to Egypt, as evidenced by the Edwin Smith and Ebers papyri. The roots of the Scientific method may be traced back to the ancient Egyptians. The ancient Egyptians are also credited with devising the world's earliest known alphabet and decimal system in the form of the Moscow and Rhind Mathematical Papyri.[16] An awareness of the Golden ratio seems to be reflected in many constructions, such as the Egyptian pyramids.

Milestones in Ancient Egyptian civilization

- 3300 B.C.E. - Bronze artifacts from this period

- 3200 B.C.E. - Egyptian hieroglyphs fully developed during the First Dynasty)

- 3200 B.C.E. - Narmer Palette, world's earliest known historical document

- 3100 B.C.E. - Decimal system,[16] world's earliest (confirmed) use

- 3100 B.C.E. - Mining in the Sinai Peninsula

- 3100 B.C.E. - 3050 B.C.E. - Shipbuilding in Abydos,[17]

- 3000 B.C.E. - Exports from Nile to Israel: wine

- 3000 B.C.E. - Copper plumbing

- 3000 B.C.E. - Egyptian medicine

- 3000 B.C.E. - Papyrus, world's earliest known paper

- 2900 B.C.E. - Senet, world's oldest (confirmed) board game

- 2700 B.C.E. - Surgery, world's earliest known

- 2700 B.C.E. - precision Surveying

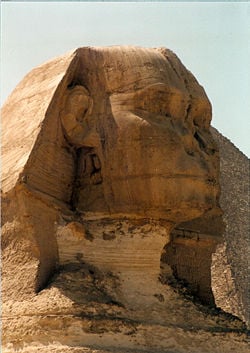

- 2600 B.C.E. - Great Sphinx of Giza, still today the world's largest single-stone statue

- 2600s-2500 B.C.E. - Shipping expeditions: King Sneferu.[18]

- 2600 B.C.E. - Barge transportation, stone blocks

- 2600 B.C.E. - Pyramid of Djoser, world's earliest known large-scale stone building

- 2600 B.C.E. - Menkaure's Pyramid & Red Pyramid, world's earliest known works of carved granite

- 2600 B.C.E. - Red Pyramid, world's earliest known "true" smooth-sided pyramid; solid granite work

- B.C.E.- Great Pyramid of Giza, the World's tallest structure until 1300 C.E.

- 2400 B.C.E. - Egyptian Astronomical Calendar, used even in the Middle Ages for its mathematical regularity

- B.C.E. - possible Nile-Red Sea Canal (Twelfth dynasty of Egypt)

- B.C.E. - Alphabet, world's oldest known

- 1800 B.C.E. - Berlin Mathematical Papyrus,[16] 2nd order algebraic equations

- 1800 B.C.E. - Moscow Mathematical Papyrus, generalized formula for volume of frustum

- 1650 B.C.E. - Rhind Mathematical Papyrus: geometry, cotangent analogue, algebraic equations, arithmetic series, geometric series

- 1600 B.C.E. - Edwin Smith papyrus, medical tradition traces as far back as c. 3000 B.C.E.

- 1550 B.C.E. - Ebers Medical Papyrus, traditional empiricism; world's earliest known documented tumors

- 1500 B.C.E. - Glass-making, world's earliest known

- 1160 B.C.E. - Turin papyrus, world's earliest known geologic and topographic map

- Other:

- c. 2500 B.C.E. - Westcar Papyrus

- c. 1800 B.C.E. - Ipuwer papyrus

- c. 1800 B.C.E. - Papyrus Harris I

- c. 1400 B.C.E. - Tulli Papyrus

- c. 1300 B.C.E. - Ebers papyrus

- Unknown date - Rollin Papyrus

Open problems

There is a question as to the sophistication of ancient Egyptian technology, and there are several open problems concerning real and alleged ancient Egyptian achievements. Certain artifacts and records do not fit with conventional technological development systems. It is not known why there is no neat progression to an Egyptian Iron Age or why the historical record shows the Egyptians taking so long to begin using iron. It is unknown how the Egyptians shaped and worked granite. The exact date the Egyptians started producing glass is debated.

Some question whether the Egyptians were capable of long distance navigation in their boats and when they become knowledgeable seamen. It is contentiously disputed as to whether or not the Egyptians had some understanding of electricity and if the Egyptians used engines or batteries. The relief at Dendera is interpreted in various ways by scholars. The topic of the Saqqara Bird is controversial, as is the extent of the Egyptians' understanding of aerodynamics. It is uncertain if the Egyptians had kites or gliders.

The pigmentation used for artwork on buildings has retained color despite thousands of years of exposure to the elements and it is not known how these paints were prepared, as modern paints are not as long lasting.

Legacy

Arnold Toynbee claimed that of the 26 civilizations he identified, Egypt was unique in having no precursor or successor. Arguably, however, the successor to Egyptian civilization was humanity itself, since Egypt bequeathed many ideas and concepts to the world in addition to mathematical and astronomological knowledge. One example is the impact of Egypt upon the Old Testament or Hebrew Bible, which continues to affect the lives of many people today.

Evidence of mummies in other civilizations and pyramids outside ancient Egypt indicate reflections of ancient Egyptian belief values on other prehistoric cultures, perhaps transmitted over the Silk Road. It is possible that Egyptians traveled to the Americas, as demonstrated by Thor Heyerdahl's Ra expeditions of 1972.[19]

It can be argued that while Egypt was a highly advanced culture religiously, technologically, politically, and culturally, it did not exert the same enduring impact on future world development that came from the small tribes of Israel that seemed somehow destined to be related to Egypt yet to perhaps to exert a greater influence. Yet another way of viewing this is to say that Israel was a channel through which aspects of Egyptian civilization spread more widely. Egyptian belief in the afterlife does not seem to have impacted much on Jewish thought, but this did find its way into much African spirituality, where a similar view of the spiritual world is still widely accepted‚ÄĒfor example, the idea of returning spirits. The pyramids were fashioned in such a way that returning the spirits could easily find their way back to the body. The view of returning ancestors and naming grandchildren after grandparents as a form of spiritual liberation of the grandparents is still prevalent in Africa today.

Israel's period of slavery in Egypt resulted in especial concern for the gerim (stranger) in their midst. Egypt may have influenced Hebrew writing, while Egyptian understanding of the role of the King as mediator between heaven and earth may have informed the Hebrew's understanding of society as subject to divine law. There are also parallels between Egyptian and Hebrew ethics. The monotheistic experiment failed in Egypt but flourished through the two related faiths of Judaism and Christianity. Both of these faiths acknowledge a certain indebtedness to Egypt, where the Septuagint (Greek version of the Bible) was translated (300-200 B.C.E.), where Philo, Origen, and Clement of Alexandria among other significant contributors to Jewish and Christian thought flourished, as later did Maimonides. Jesus' family sought refuge in Egypt, which enabled the infant Jesus to survive Herod's slaughter of the children.

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ A. Stevanovitch, A. Gilles, E. Bouzaid, R. Kefi, F. Paris, R.P. Gayraud, J.L. Spadoni, F. El-Chenawi, and E. B√©raud-Colomb, Mitochondrial DNA sequence diversity in a sedentary population from Egypt, Annals of Human Genetics 2004 Jan;68(Pt 1):23-39. Retrieved February 6, 2011.

- ‚ÜĎ F. Manni, P. Leonardi, A. Barakat, H. Rouba, E. Heyer, M. Klintschar, K. McElreavey, and L. Quintana-Murci, Y-chromosome analysis in Egypt suggests a genetic regional continuity in Northeastern Africa, Human Biology 2002 Oct;74(5):645-58. Retrieved February 6, 2011.

- ‚ÜĎ David Peter Silverman, Ancient Egypt Retrieved February 6, 2011.

- ‚ÜĎ I.E.S. Edwards, C.J. Gadd, N.G.L. Hammond, and E. Sollberger (eds.), The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume II Part I: The Middle East and the Aegean Region, c.1800-13380 B.C.E. (Cambridge University Press, 1973, ISBN 0521082307) 380.

- ‚ÜĎ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 Regine Schulz, Egypt: The World of the Pharaohs (Konemann, 1998, ISBN 3895089133).

- ‚ÜĎ Music in Ancient Egypt Digital Egypt for Universities, University College London, 2003. Retrieved February 7, 2011.

- ‚ÜĎ S.A. Macko, M.H. Engel, V. Andrusevich, G. Lubec, T.C. O'Connell, R.E. Hedges,Documenting the diet in ancient human populations through stable isotope analysis of hair, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, B Biological Sciences, 1999 Jan 29;354(1379):65-75; discussion 75-6. Retrieved February 6, 2011.

- ‚ÜĎ A. Marin, N. Cerutti, and E.R. Massa, Use of the amplification refractory mutation system (ARMS) in the study of HbS in predynastic Egyptian remains, Bollettino della Societ√† italiana di biologia sperimentale 1999 May-Jun;75(5-6):27-30. Retrieved February 6, 2011.

- ‚ÜĎ C. Perrin, V. Noly, R. Mourer, and D. Schmitt,Preservation of cutaneous structures of egyptian mummies. An ultrastructural study, Annales de Dermatologie et de V√©n√©r√©ologie 1994;121(6-7):470-5. Retrieved February 6, 2011.

- ‚ÜĎ 10.0 10.1 Eugen Strouhal, Life of the Ancient Egyptians (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1992, ISBN 9774242858)

- ‚ÜĎ Paul T. Nicholson and Ian Shaw (eds.), Ancient Egyptian Materials and Technology (Cambridge University Press, 2009, ISBN 978-0521120982)

- ‚ÜĎ Lorna Oakes, Ancient Egypt: An Illustrated Reference to the Myths, Religions, Pyramids and Temples of the Land of the Pharaohs (Barnes & Noble, 2003, ISBN 0760749434), 229

- ‚ÜĎ E. A. Wallis Budge, The Book of the Dead: The Papyrus of Ani. (1895, IAP, 2008, ISBN 978-8562022050). Retrieved February 6, 2011.

- ‚ÜĎ Caroline Seawright, Ancient Egyptian Sexuality, Tour Egypt, 1996. Retrieved February 6, 2011.

- ‚ÜĎ Jefferson Monet, An Overview of Mummification in Ancient Egypt, Tour Egypt, 1996. Retrieved February 6, 2011.

- ‚ÜĎ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Scott W. Williams, Egyptian Mathematics Papyri, Mathematicians of the African Diaspora, 2008. Retrieved February 6, 2011.

- ‚ÜĎ Francesco Raffaele, Early Dynastic Funerary boats at Abydos North. Retrieved February 6, 2011.

- ‚ÜĎ Troy Fox, The Ancient Egyptian Navy, Tour Egypt, 1996. Retrieved February 6, 2011.

- ‚ÜĎ Donald P. Ryan, The Ra Expeditions Revisited, 1997. Retrieved February 6, 2011.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Budge, E.A. Wallis. The Literature of the Ancient Egyptians Retrieved February 4, 2011. BiblioBazaar, 2009 (original 1914). ISBN 978-1113804822

- Childress, David Hatcher. Technology of the Gods: The Incredible Sciences of the Ancients. Kempton, IL: Adventures Unlimited Press, 2000. ISBN 0932813739

- Knapp, Ron. Tutankhamun and the Mysteries of Ancient Egypt. New York, NY: Julian Messner, 1979. ISBN 0671330365

- Jacq, Christian. Magic and Mystery in Ancient Egypt. London: Souvenir Press, 1998. ISBN 0285634623

- Manley, Bill (ed.). The Seventy Great Mysteries of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames & Hudson, 2003. ISBN 0500051232

- National Geographic Society. Mysteries of Egypt. National Geographic Society, 1999. ISBN 0792297520

- Nicholson, Paul T., and Ian Shaw (eds.). Ancient Egyptian Materials and Technology. Cambridge University Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0521120982

- Oakes, Lorna. Ancient Egypt: An Illustrated Reference to the Myths, Religions, Pyramids and Temples of the Land of the Pharaohs. Barnes & Noble, 2003. ISBN 0760749434

- Putnam, James. Mummy. New York, NY: Dorling Kindersley Eyewitness Guides, 1993. ISBN 0751360074

- Schulz, Regine. Egypt: The World of the Pharaohs. Konemann, 1998. ISBN 3895089133

- Sitchin, Zecharia. The Earth Chronicles Expeditions: Journeys to the Mythical Past. Rochester, VT: Bear & Co., 2004. ISBN 1591430364

- Strouhal, Eugen. Life of the Ancient Egyptians. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1992. ISBN 9774242858

External links

All links retrieved July 26, 2023.

- Ancient Egypt Online

- Catchpenny Mysteries of Ancient Egypt Larry Orcutt

- The Great Pyramid of Giza Sacred Sites

- Egyptology Groks Science Show 2004-06-30. Interview with Mark Rose, editor of Archaeology magazine.

- History of Ancient Egypt Pages translated from the Arabic Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt.

- 10 Interesting Egyptian Facts You Never Knew

| |||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.