Silk Road

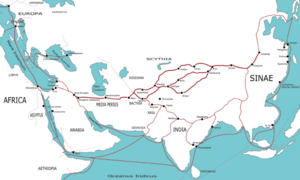

The Silk Road was an extensive interconnected network of trade routes across the Asian continent connecting East, South, and Western Asia with the Mediterranean world, including North Africa and Europe. These trade routes enabled people to transport and trade goods, especially luxuries such as silk, satins, musk, rubies, diamonds, pearls, and rhubarb from different parts of the world. The Silk road trade routes extended over 8,000 kilometers (5,000 mi). Trade on the Silk Road was a significant factor in the development of Chinese, Indian, Egyptian, Persian, Arabian, Greek, Roman, and Byzantine civilizations. It helped lay the foundations for the modern world in several respects. Although the term Silk Road implies a continuous journey, very few travelers traveled the route from end to end. For the most part, goods were transported by a series of agents on varying routes and trade took place in the bustling mercantile markets of oasis towns.

The Central Asian part of the trade route was initiated around 114 B.C.E. by the Han Dynasty largely through the missions and explorations of Zhang Qian, although earlier trade across the continents had already existed. In the late Middle Ages, use of the Silk Road declined as sea trade increased.

The Silk Road provided a conduit not only for silk, but also offered a very important path for cultural, religious and technological transmission by linking traders, merchants, pilgrims, monks, soldiers, nomads, and urban dwellers from China to the Mediterranean Sea for thousands of years.

Etymology

The first person who used the terms "Seidenstraße" and "Seidenstraßen" or "Silk Road(s)" and "Silk Route(s)," was the German geographer Ferdinand von Richthofen in 1877.[1][2]

Geographic Range

As it extends westwards from the commercial centers of North China, the continental Silk Road divides into northern and southern routes to avoid the Taklamakan Desert, and Lop Nur.

The northern route travels northwest through the Chinese province of Gansu, and splits into three further routes, two of them following the mountain ranges to the north and south of the Taklamakan Desert to rejoin at Kashgar; and the other going north of the Tian Shan mountains through Turfan, Talgar and Almaty (in what is now southeast Kazakhstan).

The routes split west of Kashgar with one branch heading down the Alai Valley towards Termez and Balkh, while the other traveled through Kokand in the Fergana Valley, and then west across the Karakum Desert towards Merv, joining the southern route briefly.

One of the branch routes turned northwest to the north of the Aral and Caspian seas then on to the Black Sea.

Yet another route started at Xi'an, passed through the Western corridor beyond the Yellow Rivers, Xinjiang, Fergana (in present-day eastern Uzbekistan), Persia (Iran), and Iraq before joining the western boundary of the Roman Empire. A route for caravans, the northern Silk Road brought to China many goods such as "dates, saffron powder and pistachio nuts from Persia; frankincense, aloes and myrrh from Somalia; sandalwood from India; glass bottles from Egypt, and other expensive and desirable goods from other parts of the world."[3] In exchange, the caravans sent back bolts of silk brocade, lacquer ware and porcelain.

The southern route is mainly a single route running through northern India, then the Turkestan–Khorasan region into Mesopotamia and Anatolia; having southward spurs enabling the journey to be completed by sea from various points. It runs south through the Sichuan Basin in China and crosses the high mountains into northeast India, probably via the Ancient tea route. It then travels west along the Brahmaputra and Ganges river plains, possibly joining the Grand Trunk Road west of Varanasi. It runs through northern Pakistan and over the Hindu Kush mountains, into Afghanistan, to rejoin the northern route briefly near Merv in present day Turkmenistan.

It then follows a nearly straight line west through mountainous northern Iran and the northern tip of the Syrian Desert to the Levant. From there, Mediterranean trading ships plied regular routes to Italy, and land routes went either north through Anatolia or south to North Africa.

Another branch road traveled from Herat through Susa to Charax Spasinu at the head of the Persian Gulf and across to Petra and on to Alexandria and other eastern Mediterranean ports from where ships carried the cargoes to Rome.

As much as fourteen hundred years ago, during China's Eastern Han Dynasty, the sea route although not part of the formal Silk Route, led from the mouth of the Red River near modern Hanoi, through the Malacca Straits to Southeast Asia, Sri Lanka and India, and then on to the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea kingdom of Axum and eventual Roman ports. From ports on the Red Sea goods, including silks, were transported overland to the Nile and then to Alexandria from where they were shipped to Rome, Constantinople, and other Mediterranean ports.[4] The Greek source for information about the specific routes and ports is the Periplus Maris Erythraei.[5] Another branch of these sea routes led down the East African coast (called "Azania" by the Greeks and Romans and "Zesan" by the Chinese) at least as far as the port known to the Romans as "Rhapta," which was probably located in the delta of the Rufiji River in modern Tanzania.

Prehistory

Cross-continental journeys

As the domestication of pack animals and the development of shipping technology both increased the capacity for prehistoric peoples to carry heavier loads over greater distances, cultural exchanges and trade developed rapidly.

In addition, grassland provided fertile grazing, water, and easy passage for caravans. The vast grassland steppes of Asia enabled merchants to travel immense distances, from the shores of the Pacific to Africa and deep into Europe, without trespassing on agricultural lands and arousing hostility.

Evidence for ancient transport and trade routes

The ancient peoples of the Sahara imported domesticated animals from Asia between 6000 and 4000 B.C.E. In Nabta Playa, by the end of the seventh millennium B.C.E., prehistoric Egyptians had imported goats and sheep from Southwest Asia.[6]

Foreign artifacts dating to the fifth millennium B.C.E. in the Badarian culture of Egypt indicate contact with distant Syria.

By the fourth millennium B.C.E. shipping was well established, and the donkey and possibly the dromedary had been domesticated. Domestication of the Bactrian camel and use of the horse for transport then followed.

Charcoal samples found in the tombs of Nekhen (Greek name was Hierakonpolis), which were dated to the Naqada I and II periods, (4400–3200 B.C.E.) have been identified as cedar from Lebanon.[7]

By the second half of the fourth millennium B.C.E., the blue gemstone lapis lazuli was being traded from its only known source in the ancient world—Badakshan, in what is now northeastern Afghanistan—as far as Mesopotamia and Egypt. By the third millennium B.C.E., the lapis lazuli trade was extended to Harappa and Mohenjo-daro in the Indus Valley Civilization (Ancient India) of modern day Pakistan and northwestern India. The Indus Valley culture was also known as Meluhha, the earliest maritime trading partner of the Sumerians and Akkadians in Mesopotamia. The ancient harbor on the Gulf of Cambay, constructed in Lothal, India, around 2400 B.C.E. is the oldest seafaring harbor known.

Routes along the Persian Royal Road, constructed in the fifth century B.C.E. by Darius I of Persia, may have been in use as early as 3500 B.C.E.

Ancient Egyptians already knew how to assemble planks of wood into a ship hull as early as 3000 B.C.E.[8] Woven straps were used to lash the planks together, and reeds or grass stuffed between the planks helped to seal the seams.

Egyptian maritime trade

The Palermo stone mentions King Sneferu of the 4th Dynasty sending ship to import high-quality cedar from Lebanon. In one scene in the pyramid of Pharaoh Sahure of the Fifth Dynasty, Egyptians are returning with huge cedar trees. Sahure's name is found stamped on a thin piece of gold on a Lebanon chair, and 5th dynasty cartouches were found in Lebanon stone vessels. Other scenes in his temple depict Syrian bears.

The oldest known expedition to the Land of Punt was organized by Sahure, which apparently yielded a quantity of myrrh, along with malachite and electrum. The 12th Dynasty Pharaoh Senusret III had a "Suez" canal constructed linking the Nile River with the Red Sea for direct trade with Punt. Around 1950 B.C.E., in the reign of Mentuhotep III, an officer named Hennu made one or more voyages to Punt. In the fifteenth century B.C.E., Nehsi conducted a very famous expedition for Queen Hatshepsut to obtain myrrh; a report of that voyage survives on a relief in Hatshepsut's funerary temple at Deir el-Bahri. Several of her successors, including Thutmoses III, also organized expeditions to Punt.

Shipping via an ancient "Suez" Canal continued by the efforts of Necho II, Darius I of Persia and Ptolemy II Philadelphus. Shipping over the Nile River and from Old Cairo and through Suez continued by the efforts of either 'Amr ibn al-'As,[9] Omar the Great,[10] or Trajan.[9][10] The Abbasid Caliph al-Mansur is said to have ordered this ancient canal closed so as to prevent supplies from reaching Arabian detractors.[9][10]

Iranian and Scythian connections

The expansion of Scythian Iranian cultures stretching from the Hungarian plain and the Carpathians to the Chinese Kansu Corridor and linking Iran, and the Middle East with Northern India and the Punjab, undoubtedly played an important role in the development of the Silk Road. Scythians accompanied the Assyrian Esarhaddon on his invasion of Egypt, and their distinctive triangular arrowheads have been found as far south as Aswan. These nomadic peoples were dependent upon neighboring settled populations for a number of important technologies, and in addition to raiding vulnerable settlements for these commodities, also encouraged long distance merchants as a source of income through the enforced payment of tariffs. Soghdian Scythian merchants played a vital role in later periods in the development of the Silk Road.

Chinese and Central Asian contacts

From the second millennium B.C.E. nephrite jade was being traded from mines in the region of Yarkand and Khotan to China. Significantly, these mines were not very far from the lapis lazuli and spinel ("Balas Ruby") mines in Badakhshan and, although separated by the formidable Pamir Mountains, routes across them were, apparently, in use from very early times.

The Tarim mummies, Chinese mummies of non-Mongoloid, apparently Caucasoid, individuals, have been found in the Tarim Basin, in the area of Loulan located along the Silk Road 200 km east of Yingpan, dating to as early as 1600 B.C.E. and suggesting very ancient contacts between East and West. It has been suggested that these mummified remains may have been of people related to the Tocharians whose Indo-European language remained in use in the Tarim Basin (modern day Xinjiang) of China until the eighth century.

Some remnants of what was probably Chinese silk have been found in Ancient Egypt from 1070 B.C.E. Though the originating source seems sufficiently reliable, silk unfortunately degrades very rapidly and it cannot be double-checked for accuracy whether it was actually cultivated silk (which would almost certainly have come from China) that was discovered or a type of "wild silk," which might have come from the Mediterranean region or the Middle East.

Following contacts of metropolitan China with nomadic western border territories in the eighth century B.C.E., gold was introduced from Central Asia, and Chinese jade carvers began to make imitation designs of the steppes, adopting the Scythian-style animal art of the steppes (descriptions of animals locked in combat). This style is particularly reflected in the rectangular belt plaques made of gold and bronze with alternate versions in jade and steatite.

Persian Royal Road

By the time of Herodotus (c. 475 B.C.E.), the Persian Royal Road ran some 2,857 km from the city of Susa on the lower Tigris to the port of Smyrna (modern İzmir in Turkey) on the Aegean Sea. It was maintained and protected by the Achaemenid Empire (c. 500–330 B.C.E.) and had postal stations and relays at regular intervals. By having fresh horses and riders ready at each relay, royal couriers could carry messages the entire distance in nine days, though normal travelers took about three months. This Royal Road linked into many other routes. Some of these, such as the routes to India and Central Asia, were also protected by the Achaemenids, encouraging regular contact between India, Mesopotamia and the Mediterranean. There are accounts in Esther of dispatches being sent from Susa to provinces as far out as India and Cush during the reign of Xerxes (485–465 B.C.E.).

History

Hellenistic era

The first major step in opening the Silk Road between the East and the West came with the expansion of Alexander the Great's empire into Central Asia. In August 329 B.C.E., at the mouth of the Fergana Valley in Tajikistan he founded the city of Alexandria Eschate or "Alexandria The Furthest."[11] This later became a major staging point on the northern Silk Route.

In 323 B.C.E., Alexander the Great’s successors, the Ptolemaic dynasty, took control of Egypt. They actively promoted trade with Mesopotamia, India, and East Africa through their Red Sea ports and over land. This was assisted by a number of intermediaries, especially the Nabataeans and other Arabs.

The Greeks remained in Central Asia for the next three centuries, first through the administration of the Seleucid Empire, and then with the establishment of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom in Bactria. They continued to expand eastward, especially during the reign of Euthydemus (230-200 B.C.E.) who extended his control beyond Alexandria Eschate to Sogdiana. There are indications that he may have led expeditions as far as Kashgar in Chinese Turkestan, leading to the first known contacts between China and the West around 200 B.C.E. The Greek historian Strabo writes "they extended their empire even as far as the Seres (China) and the Phryni."[12]

Chinese exploration of Central Asia

The next step came around 130 B.C.E., with the embassies of the Han Dynasty to Central Asia, following the reports of the ambassador Zhang Qian[13] (who was originally sent to obtain an alliance with the Yuezhi against the Xiongnu). The Chinese Emperor Wu Di became interested in developing commercial relationships with the sophisticated urban civilizations of Ferghana, Bactria and Parthia: "The Son of Heaven on hearing all this reasoned thus: Ferghana (Dayuan) and the possessions of Bactria (Ta-Hsia) and Parthia (Anxi) are large countries, full of rare things, with a population living in fixed abodes and given to occupations somewhat identical with those of the Chinese people, but with weak armies, and placing great value on the rich produce of China" (Hou Hanshu, Later Han History).

The Chinese were also strongly attracted by the tall and powerful horses in the possession of the Dayuan (named "Heavenly horses"), which were of capital importance in fighting the nomadic Xiongnu. The Chinese subsequently sent numerous embassies, around ten every year, to these countries and as far as Seleucid Syria. "Thus more embassies were dispatched to Anxi [Parthia], Yancai (who later joined the Alans), Lijian (Syria under the Seleucids), Tiaozhi [Chaldea], and Tianzhu (northwestern India)… As a rule, rather more than ten such missions went forward in the course of a year, and at the least five or six" (Hou Hanshu, Later Han History). The Chinese campaigned in Central Asia on several occasions, and direct encounters between Han troops and Roman legionaries (probably captured or recruited as mercenaries by the Xiong Nu) are recorded, particularly in the 36 B.C.E. battle of Sogdiana. It has been suggested that the Chinese crossbow was transmitted to the Roman world on such occasions, although the Greek gastraphetes provides an alternative origin. R. Ernest Dupuy and Trevor N. Dupuy suggest that in 36 B.C.E., a "Han expedition into central Asia, west of Jaxartes River, apparently encountered and defeated a contingent of Roman legionaries. The Romans may have been part of Antony's army invading Parthia. Sogdiana (modern Bukhara), east of the Oxus River, on the Polytimetus River, was apparently the most easterly penetration ever made by Roman forces in Asia. The margin of Chinese victory appears to have been their crossbows, whose bolts and darts seem easily to have penetrated Roman shields and armor."[14]

The Roman historian Florus also describes the visit of numerous envoys, included Seres (Chinese), to the first Roman Emperor Augustus, who reigned between 27 and 14 B.C.E.:

Even the rest of the nations of the world which were not subject to the imperial sway were sensible of its grandeur, and looked with reverence to the Roman people, the great conqueror of nations. Thus even Scythians and Sarmatians sent envoys to seek the friendship of Rome. Nay, the Seres came likewise, and the Indians who dwelt beneath the vertical sun, bringing presents of precious stones and pearls and elephants, but thinking all of less moment than the vastness of the journey which they had undertaken, and which they said had occupied four years. In truth it needed but to look at their complexion to see that they were people of another world than ours ("Cathay and the way thither," Henry Yule).

The "Silk Road" essentially came into being from the first century B.C.E., following these efforts by China to consolidate a road to the Western world and India, both through direct settlements in the area of the Tarim Basin and diplomatic relations with the countries of the Dayuan, Parthians, and Bactrians further west. The Han Dynasty Chinese army regularly policed the trade route against nomadic bandit forces generally identified as the Xiongnu/Huns. Han general Ban Chao led an army of 70,000 mounted infantry and light cavalry troops in the first century C.E. to secure the trade routes, reaching far west across central Asia to the doorstep of Europe, and setting up base on the shores of the Caspian Sea in cooperation with the Parthian Kingdom under Pacorus II of Parthia.

A maritime "Silk Route" opened up between Chinese-controlled Giao Chỉ (centred in modern Vietnam [see map above], near Hanoi) probably by the first century. It extended, via ports on the coasts of India and Sri Lanka, all the way to Roman-controlled ports in Egypt and the Nabataean territories on the northeastern coast of the Red Sea.

The Roman Empire

Soon after the Roman conquest of Egypt in 30 B.C.E., regular communications and trade between India, Southeast Asia, Sri Lanka, China, the Middle East, Africa and Europe blossomed on an unprecedented scale. The traveler Maës Titianus allegedly penetrated farthest east along the Silk Road from the Mediterranean world, probably with the aim of regularizing contacts and reducing the role of middlemen, during one of the lulls in Rome's intermittent wars with Parthia, which repeatedly obstructed movement along the Silk Road. Land and maritime routes were closely linked, and novel products, technologies and ideas began to spread across the continents of Europe, Asia and Africa. Intercontinental trade and communication became regular, organized, and protected by the "Great Powers." Intense trade with the Roman Empire followed soon, confirmed by the Roman craze for Chinese silk (supplied through the Parthians), even though the Romans thought silk was obtained from trees. This belief was affirmed by Seneca the Younger in his Phaedra and by Virgil in his Georgics. Notably, Pliny the Elder knew better. Speaking of the bombyx or silk moth, he wrote in his Natural Histories "They weave webs, like spiders, that become a luxurious clothing material for women, called silk."[15]

The Senate issued, in vain, several edicts to prohibit the wearing of silk, on economic and moral grounds: The importation of Chinese silk caused a huge outflow of gold, and silk clothes were considered to be decadent and immoral:

I can see clothes of silk, if materials that do not hide the body, nor even one's decency, can be called clothes… Wretched flocks of maids labour so that the adulteress may be visible through her thin dress, so that her husband has no more acquaintance than any outsider or foreigner with his wife's body (Seneca the Younger (c. 3 B.C.E.–65, Declamations Vol. I).

The Hou Hanshu records that the first Roman envoy arrived in China by this maritime route in 166 C.E., initiating a series of Roman embassies to China.

Medieval era

The main traders during Antiquity were the Indian and Bactrian traders, then from the fifth to the eighth century C.E. the Sogdian traders, then afterward the Persian traders.

The unification of Central Asia and Northern India within the Kushan empire in the first to third centuries reinforced the role of the powerful merchants from Bactria and Taxila.[16] They fostered multi-cultural interaction as indicated by their second century treasure hoards filled with products from the Greco-Roman world, China and India, such as in the archeological site of Begram in present day Afghanistan.

The heyday of the Silk Road corresponds, on its west end, to the Byzantine Empire, Sassanid Empire Period to Il Khanate Period in the Nile-Oxus section and Three Kingdoms to Yuan Dynasty in the Sinitic zone in its east end. Trade between East and West also developed on the sea, between Alexandria in Egypt and Guangzhou in China, fostering across the Indian Ocean. The Silk Road represents an early phenomenon of political and cultural integration due to inter-regional trade. In its heyday, the Silk Road sustained an international culture that strung together groups as diverse as the Magyars, Armenians, and Chinese.

Under its strong integrating dynamics on the one hand and the impacts of change it transmitted on the other, tribal societies previously living in isolation along the Silk Road or pastoralists who were of barbarian cultural development were drawn to the riches and opportunities of the civilizations connected by the Silk Road, taking on the trades of marauders or mercenaries. Many barbarian tribes became skilled warriors able to conquer rich cities and fertile lands, and forge strong military empires.

The Sogdians dominated the East-West trade after the fourth century C.E. up to the eighth century C.E., with Suyab and Talas ranking among their main centers in the north. They were the main caravan merchants of Central Asia. Their commercial interests were protected by the resurgent military power of the Göktürks, whose empire has been described as "the joint enterprise of the Ashina clan and the Soghdians."[17] Their trades with some interruptions continued in the ninth century within the framework of the Uighur Empire, which until 840 extended across northern Central Asia and obtained from China enormous deliveries of silk in exchange for horses. At this time caravans of Sogdians traveling to Upper Mongolia are mentioned in Chinese sources. They played an equally important religious and cultural role. Part of the data about eastern Asia provided by Muslim geographers of the tenth century actually goes back to Sogdian data of the period 750-840 and thus shows the survival of links between east and west. However, after the end of the Uighur Empire in 840, Sogdian trade went through a crisis. What mainly issued from Muslim Central Asia was the trade of the Samanids, which resumed the northwestern road leading to the Khazars and the Urals and the northeastern one toward the nearby Turkic tribes.

The Silk Road gave rise to the clusters of military states of nomadic origins in North China, invited the Nestorian, Manichaean, Buddhist, and later Islamic religions into Central Asia and China, created the influential Khazar Federation and at the end of its glory, brought about the largest continental empire ever: The Mongol Empire, with its political centers strung along the Silk Road (Beijing in North China, Karakorum in central Mongolia, Sarmakhand in Transoxiana, Tabriz in Northern Iran, Sarai and Astrakhan in lower Volga, Solkhat in Crimea, Kazan in Central Russia, Erzurum in eastern Anatolia), realizing the political unification of zones previously loosely and intermittently connected by material and cultural goods.

The Roman Empire, and its demand for sophisticated Asian products, crumbled in the West around the fifth century. In Central Asia, Islam expanded from the seventh century onward, bringing a stop to Chinese westward expansion at the Battle of Talas in 751. Further expansion of the Islamic Turks in Central Asia from the tenth century completed the disruption of trade in that vast part of the world, and Buddhism almost disappeared. For much of the Middle Ages, the Islamic Caliphate in Persia often had a monopoly over much of the trade conducted across the Old World.

Mongol era

The Mongol expansion throughout the Asian continent from around 1215 to 1360 helped bring political stability and re-establish the Silk Road (via Karakorum). The Chinese Mongol diplomat Rabban Bar Sauma visited the courts of Europe in 1287-1288 and provided a detailed written report back to the Mongols. Around the same time, the Venetian explorer Marco Polo became one of the first Europeans to travel the Silk Road to China, and his tales, documented in Ptolemaic dynasty, opened Western eyes to some of the customs of the Far East. He was not the first to bring back stories, but he was one of the widest-read. He had been preceded by numerous Christian missionaries to the East, such as William of Rubruck, Benedykt Polak, Giovanni da Pian del Carpine, and Andrew of Longjumeau. Later envoys included Odoric of Pordenone, Giovanni de' Marignolli, John of Montecorvino, Niccolò Da Conti, or Ibn Battuta, a Moroccan Muslim traveller, who passed through the present-day Middle East and across the Silk Road from Tabriz, between 1325-1354.[18][19]

The thirteenth century also saw attempts at a Franco-Mongol alliance, with exchange of ambassadors and (failed) attempts at military collaboration in the Holy Land during the later Crusades, though the Mongols in the Ilkhanate, after they had destroyed the Abbasid and Ayyubid dynasties, eventually themselves converted to Islam, and signed the 1323 Treaty of Aleppo with the surviving Muslim power, the Egyptian Mamluks.

Disintegration

However, with the disintegration of the Mongol Empire also came discontinuation of the Silk Road's political, cultural and economic unity. Turkmeni marching lords seized the western part of the Silk Road—the decaying Byzantine Empire. After the Mongol Empire, the great political powers along the Silk Road became economically and culturally separated. Accompanying the crystallization of regional states was the decline of nomad power, partly due to the devastation of the Black Death and partly due to the encroachment of sedentary civilizations equipped with gunpowder.

The effect of gunpowder and early modernity on Europe was the integration of territorial states and increasing mercantilism; whereas on the Silk Road, gunpowder and early modernity had the opposite impact: the level of integration of the Mongol Empire could not be maintained, and trade declined (though partly due to an increase in European maritime exchanges).

The great explorers: Europe reaching for Asia

The disappearance of the Silk Road following the end of the Mongols was one of the main factors that stimulated the Europeans to reach the prosperous Chinese empire through another route, especially by sea. Tremendous profits were to be obtained for anyone who could achieve a direct trade connection with Asia.

When he went West in 1492, Christopher Columbus reportedly wished to create yet another Silk Route to China. It was initially a great disappointment to have found a continent "in-between" before recognizing the potential of a "New World."

In 1594, Willem Barents left Amsterdam with two ships to search for the Northeast passage north of Siberia, on to eastern Asia. He reached the west coast of Novaya Zemlya and followed it northward, being finally forced to turn back when confronted with its northern extremity. By the end of the seventeenth century, the Russians re-established a land trade route between Europe and China under the name of the Great Siberian Road.

The desire to trade directly with China was also the main driving force behind the expansion of the Portuguese beyond Africa after 1480, followed by the Netherlands and Great Britain from the seventeenth century.

In the eighteenth century, Adam Smith declared that China had been one of the most prosperous nations in the world, but that it had remained stagnant for a long time and its wages always were low and the lower classes were particularly poor:

China has been long been one of the richest, that is, one of the most fertile, best cultivated, most industrious, and most populous countries in the world. It seems, however, to have been long stationary. Marco Polo, who visited it more than five hundred years ago, describes its cultivation, industry, and populousness, almost in the same terms as travellers in the present time describe them. It had perhaps, even long before his time, acquired that full complement of riches which the nature of its laws and institutions permits it to acquire (Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, 1776).

In effect, the spirit of the Silk Road and the will to foster exchange between the East and West, as well as the lure of huge profits attached to doing so has affected much of the history of the world during these last three millennia.

Cultural exchanges on the Silk Road

Notably, the Buddhist faith and the Greco-Buddhist culture started to travel eastward along the Silk Road, penetrating China from around the first century B.C.E.

The Silk Road transmission of Buddhism to China started in the first century C.E. with a semi-legendary account of an embassy sent to the West by the Chinese Emperor Ming (58–75 C.E.). Extensive contacts however started in the second century C.E., probably as a consequence of the expansion of the Kushan empire into the Chinese territory of the Tarim Basin, with the missionary efforts of a great number of Central Asian Buddhist monks to Chinese lands. The first missionaries and translators of Buddhists scriptures into Chinese were either Parthian, Kushan, Sogdian, or Kuchean.

From the fourth century onward, Chinese pilgrims also started to travel to India, the origin of Buddhism, by themselves in order to get improved access to the original scriptures, with Fa-hsien's pilgrimage to India (395–414), and later Xuan Zang (629–644). The Silk Road transmission of Buddhism essentially ended around the seventh century with the rise of Islam in Central Asia.

Artistic transmission

Many artistic influences transited along the Silk Road, especially through the Central Asia, where Hellenistic, Iranian, Indian, and Chinese influences were able to intermix. In particular, Greco-Buddhist art represents one of the most vivid examples of this interaction.

Buddhist deities

The image of the Buddha, originating during the first century in northern India (areas of Gandhara and Mathura) was transmitted progressively through Central Asia and China until it reached Korea in the fourth century and Japan in the sixth century. However the transmission of many iconographical details are clear, such as the Hercules inspiration behind the Nio guardian deities in front of Japanese Buddhist temples, and also representations of the Buddha reminiscent of Greek art such as the Buddha in Kamakura.

Another Buddhist deity, Shukongoshin, is also an interesting case of transmission of the image of the famous Greek god Herakles to the Far East along the Silk Road. Herakles was used in Greco-Buddhist art to represent Vajrapani, the protector of the Buddha, and his representation was then used in China, Korea, and Japan to depict the protector gods of Buddhist temples.

Wind god

The name of the west wind in Greek is Zephyr. Various other artistic influences from the Silk Road can be found in Asia, one of the most striking being that of the Greek Wind God Boreas, transiting through Central Asia and China to become the Japanese Shinto wind god Fujin.

Floral scroll pattern

Finally the Greek artistic motif of the floral scroll was transmitted from the Hellenistic world to the area of the Tarim Basin around the second century, as seen in Serindian art and wooden architectural remains. It was then adopted by China between the fourth and sixth century and displayed on tiles and ceramics; afterward, it was transmitted to Japan in the form of roof tile decorations of Japanese Buddhist temples circa seventh century, particularly in Nara temple building tiles, some of them exactly depicting vines and grapes.

Technological transfer

The period of the High Middle Ages in Europe and East Asia saw major technological advances, including the diffusion through the Silk Road of the precursor to movable type printing, gunpowder, the astrolabe, and the compass.

Korean maps such as the Kangnido and Islamic map making seem to have influenced the emergence of the first European practical world maps, such as those of De Virga or Fra Mauro. Ramusio, a contemporary, states that Fra Mauro's map is "an improved copy of the one brought from Cathay by Marco Polo."

Large Chinese junks were also observed by these travelers and may have provided impetus to develop larger ships in Europe.

Notes

- ↑ Vadime Eliseeff (ed.), "Approaches Old and New to the Silk Roads," in The Silk Roads: Highways of Culture and Commerce (Paris: UNESCO, 1998, ISBN 9231036521).

- ↑ Daniel Waugh, "Richthofen 'Silk Roads': Toward the Archeology of a Concept," The Silk Road 5 (1) (Summer 2007): 4.

- ↑ Ulric Killion, A Modern Chinese Journey to the West: Economic Globalization And Dualism (Hauppauge NY: Nova Science Publishers: 2006), 66

- ↑ Lionel Casson, The Periplus Maris Erythraei. Text with Introduction, Translation, and Commentary (Princeton University Press, 1989, ISBN 0691040605).

- ↑ Fordham University, The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea: Travel and Trade in the Indian Ocean by a Merchant of the First Century, Ancient History Sourcebook. Retrieved October 27, 2008.

- ↑ Fred Wendorf and Romuald Schild, Late Neolithic megalithic structures at Nabta Playa (Sahara), southwestern Egypt. Retrieved October 20, 2008.

- ↑ Marie Parsons, Egypt: Hierakonpolis, A Feature Tour Egypt Story. Retrieved October 20, 2008.

- ↑ Cheryl Ward, "World's Oldest Planked Boats," Archaeology 54 (3) (May/June 2001).

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Encyclopaedia Britannica, Suez Canal. Retrieved October 20, 2008.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 S. Rappoport, Doctor of Philosophy, Basel, History of Egypt (London: The Grolier Society.)

- ↑ John Prevas, Envy of the Gods: Alexander the Great's Ill-Fated Journey across Asia (De Capo Press, 2004, ISBN 0306812681), 121.

- ↑ Strabo, Geography XI.XI.I. Retrieved October 20, 2008.

- ↑ A. Burnham (ed.), Silk Road, North China. Retrieved October 20, 2008.

- ↑ R. Ernest Dupuy and Trevor N. Dupuy, The Harper Encyclopedia of Military History from 3500 B.C.E. to the Present, Fourth Edition (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1993), 133.

- ↑ Pliny the Elder, Natural Histories, 11.xxvi.76

- ↑ Encyclopedia Iranica, Sogdian Trade. Retrieved October 20, 2008.

- ↑ Andre Andre Wink, Al-Hind: The Making of the Indo-Islamic World (Brill Academic Publishers, 2002, ISBN 0391041738).

- ↑ Daniel C. Waugh, The Pax Mongolica, University of Washington, Seattle. Retrieved October 20, 2008.

- ↑ Battuta's Travels, Part Three—Persia and Iraq. Retrieved October 20, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Boulnois, Luce. Silk Road: Monks, Warriors & Merchants. Hong Kong: Odyssey Books, 2005. ISBN 9622177212.

- Boulnois, Luce. 2004. Silk Road: Monks, Warriors & Merchants on the Silk Road, Translated by Helen Loveday with additional material by Bradley Mayhew and Angela Sheng. Airphoto International. ISBN 9622177212.

- Casson, Lionel. 1989. The Periplus Maris Erythraei. Text with Introduction, Translation, and Commentary. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691040605.

- Dupuy, R. Ernest, and Trevor N. Dupuy. The Harper Encyclopedia of Military History from 3500 B.C.E. to the Present, Fourth Ed. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1993. ISBN 0062700561.

- Elisseeff, Vadime (ed.). The Silk Roads: Highways of Culture and Commerce. UNESCO Publishing / Berghahn Books. 2001. ISBN 9789231036521.

- Hopkirk, Peter. Foreign Devils on the Silk Road: The Search for the Lost Cities and Treasures of Chinese Central Asia. Amherst: The University of Massachusetts Press, (1980) 1984. ISBN 0870234358.

- Huyghe, Edith and François-Bernard Huyghe. La route de la soie ou les empires du mirage. Petite bibliothèque Payot, 2006, ISBN 2228900737.

- Juliano, Annettte, L. and Judith A. Lerner, et al. 2002. Monks and Merchants: Silk Road Treasures from Northwest China: Gansu and Ningxia, 4th-7th Century. Harry N. Abrams Inc., with The Asia Society. ISBN 0878480897.

- Killion, Ulric. A Modern Chinese Journey to the West: Economic Globalization And Dualism. Hauppauge NY: Nova Science Publishers, 2006. ISBN 1594549052

- Klimkeit, Hans-Joachim. 1993. Gnosis on the Silk Road: Gnostic Texts from Central Asia, Trans. & presented by Hans-Joachim Klimkeit. HarperSanFrancisco. ISBN 0060645865.

- Li, Rongxi, (translator). 1995. A Biography of the Tripiṭaka Master of the Great Ci’en Monastery of the Great Tang Dynasty. Berkeley, CA: Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research. ISBN 1886439001.

- Li, Rongxi, (translator). 1995. The Great Tang Dynasty Record of the Western Regions. Berkeley, CA: Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research. ISBN 1886439028.

- Malkov, Artemy. 2007. "The Silk Road: A mathematical model." History & Mathematics, ed. by Peter Turchin et al. Moscow: KomKniga. ISBN 9785484010028.

- Ming Pao. Hong Kong proposes Silk Road on the Sea as World Heritage, August 7 2005, p. A2.

- Prevas, John. 2004. Envy of the Gods: Alexander the Great's Ill-Fated Journey across Asia. De Capo Press, ISBN 0306812681.

- Ray, Himanshu Prabha, 2003. The Archaeology of Seafaring in Ancient South Asia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521011094.

- Schafer, Edward H. 1963. The Golden Peaches of Samarkand: A study of T’ang Exotics. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. 1985. ISBN 0520054628.

- Waugh, Daniel, "Richthofen "Silk Roads": Toward the Archeology of a Concept." The Silk Road 5 (1) (Summer 2007).

- Wimmel, Kenneth, 1996. The Alluring Target: In Search of the Secrets of Central Asia. Palo Alto, CA: Trackless Sands Press. ISBN 1879434482.

- Wink, André. Al-Hind: The Making of the Indo-Islamic World. Brill Academic Publishers, 2002. ISBN 0391041738.

- Wood, Francis. The Silk Road: Two Thousand Years in the Heart of Asia. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. 2002 pp. 9, 13-23 ISBN 9780520243408.

- Yan, Chen, 1986. "Earliest Silk Route: The Southwest Route." in Chen Yan. China Reconstructs Vol. XXXV, No. 10. (Oct. 1986): 59–62.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.