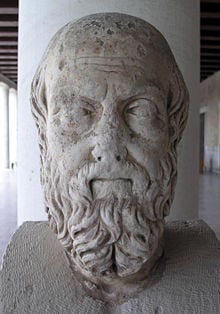

Herodotus

Herodotus of Halicarnassus (in Greek, Ἡρόδοτος Ἁλικαρνᾱσσεύς, Herodotos Halikarnasseus) was a Dorian Greek historian who lived in the fifth century B.C.E. (484 B.C.E. – 425 B.C.E.) Dubbed "the father of history" by the Roman orator Cicero, he was the author of the first narrative history produced in the ancient world. The Histories was a collection of 'inquiries' (or 'ἱστορια', a word which passed into Latin and took on its modern connotation of 'history'), in nine volumes, about the places and peoples he encountered during his wide-ranging travels around the Mediterranean.

The theme for this work, stately boldly by the author in the Prologue, was "to preserve the memory of the past by putting on record the astonishing achievements both of the Greek and the non-Greek peoples; and more particularly, to show how the two races came into conflict." Herodotus' intention to preserve the memory of the past as a salutary, objective record, rather than a self-serving annal in the defense of a political regime, was a landmark achievement. His work advanced historical study as an objective discipline rather than partisan exercise and anticipated the work of his younger, more rigorous, contemporary, Thucydides.

The study of history is critical to humanity's self-knowledge, offering object lessons in both the management and mismanagement of human affairs, hindsight into trains of events that follow from sometimes incidental occurrences, and even insights into patterns or movements that repeat in different ages and among different peoples. As the British philosopher George Santayana famously observed, "Those who don't learn from the past are destined to repeat it."

Herodotus' history recounts the Persian invasions of Greece in 490 and 480 B.C.E., the heroic Greek defense against the invaders, and the final Greek victory. The dramatic battles at Thermopylae and Salamis recorded by Herodotus are among the most famous and consequential in history, preserving Greek independence, providing a short-lived era of cooperation among the contentious Greek city-states, and most importantly enabling full flowering of classical Greek civilization.

Herodotus recorded many details about contemporary life in the countries which he visited, creating an invaluable source for later historians and archaeologists. His method was to recount all the known versions of a particular incident, then choose the one he thought most plausible. Herodotus has been criticized for including myths and legends in his history to add interest to his accounts. Modern scholars are more appreciative and consider him to be not only a pioneer in historiography but in anthropology and ethnography because of the information he gathered on his numerous journeys.

Life

The little that is known of the life of Herodotus has been mostly gleaned from his own works. Herodotus was born a Persian subject c. 484 B.C.E. at Halicarnassus in Asia Minor (now Bodrum, Turkey), and remained a Persian subject until the age of thirty or thirty-five. At the time of Herodotus’ birth, Halicarnassus was ruled by a Queen Artemisia, who was succeeded by her son Pisindelis (born c. 498 B.C.E.). His son Lygdamis took the throne around the time that Herodotus reached adulthood. His father Lyxes and mother Rhaeo (or Dryo) belonged to the upper class. Herodotus had a brother Theodore and an uncle or cousin named Panyasis, who was an epic poet and important enough to be considered a threat and was accordingly put to death by Lygdamis. Herodotus was either exiled or left Hallicarnassus voluntarily at the time of Panyasis’ execution.

Herodotous received a Greek education, and being unable to enter politics because of the oppression of a tyrannical government, turned to literature. His extant works demonstrate that he was intimately acquainted with the Iliad and the Odyssey and the poems of the epic cycle, including the Cypria, the Epigoni. He quotes or otherwise shows familiarity with the writings of Hesiod, Olen, Musaeus, Bacis, Lysistratus, Archilochus of Paros, Alcaeus, Sappho, Solon, Aesop, Aristeas of Proconnesus, Simonides of Ceos, Phrynichus, Aeschylus and Pindar. He quotes and criticizes Hecataeus, the best of the prose writers who had preceded him, and makes numerous allusions to other authors of the same class.

Herodotus traveled across Asia Minor and European Greece more than once, and visited all the most important islands of the Archipelago, Rhodes, Cyprus, Delos, Paros, Thasos, Samothrace, Crete, Samos, Cythera and Aegina. He undertook the long and perilous journey from Sardis to the Persian capital Susa, visited Babylon, Colchis, and the western shores of the Black Sea as far as the estuary of the Dnieper; he travelled in Scythia and in Thrace, visited Zante and Magna Graecia, explored the antiquities of Tyre, coasted along the shores of Palestine, saw Ga~a, and made a long stay in Egypt. His travels are estimated to have crossed thirty-one degrees of longitude, or 1700 miles, and twenty-four of latitude, nearly the same distance. He remained for some time at all the more interesting sites and examined, inquired, made measurements, and gathered materials for his great work. He carefully obtained by personal observation a full knowledge of the various countries.

Herodotus seem to have made most of his journeys between the ages of 20 and 37 (464 - 447 B.C.E.). It was probably during his early manhood he visited Susa and Babylon as a Persian subject, taking advantage of the Persian system of posts which he describes in his fifth book. His residence in Egypt must have occurred after 460 B.C.E., because he reports seeing the skulls of the Persians slain by Inarus in that year. Skulls are rarely visible on a battlefield for more than two or three years after a battle, making it probable that Herodotus visited Egypt during the reign of Inarus (460-454 B.C.E.), when the Athenians had authority in Egypt, and that he made himself known as a learned Greek. On his return from Egypt, as he proceeded along the Syrian shore, he seems to have landed at Tyre, and to have gone on to Thasos from there. His Scythian travels are thought to have taken place prior to 450 B.C.E.

Historians question what city Herodotus used as his headquarters while he was making all his travels. Up to the time of the execution of Panyasis, which is placed by chronologists in or about the year 457 B.C.E., Herodotus probably resided at Halicarnassus. His travels in Asia Minor, in European Greece, and among the islands of the Aegean, probably belonged to this period, as also his journey to Susa and Babylon. When Herodotus quitted Halicarnassus on account of the tyranny of Lygdamis, about the year 457 B.C.E., he went to Samos. That island was an important member of the Athenian confederacy, and in making it his home Herodotus would have put himself under the protection of Athens. Egypt was then largely under the influence of Athens, making it possible for him to travel there in 457 or 456 B.C.E. The stories that he heard in Egypt of Sesostris may have inspired him to make voyages from Samos to Colchis, Scythia and Thrace.

Herodotus had resided in Samos for seven or eight years, until Lygdamis was expelled from the throne and he was able to return to Hallicarnassus. According to Suidas, Herodotus was himself a rebel against Lygdamis; but no other author confirms this. Halicarnassus became a voluntary member of the Athenian confederacy, and Herodotus could now return and enjoy the rights of free citizenship in his native city. Around 447 B.C.E. he suddenly went to Athens, and there is evidence that he went there because his work was not well received in Hallicarnassus. In Athens his work won such approval that in the year 445 B.C.E., at the proposal of a certain Anytus, he was voted a sum of ten talents (£2400) by decree of the people. At one of the recitations, it was said, the future historian Thucydides was present with his father, Olorus, and was so moved that he burst into tears, whereupon Herodotus remarked to the father,"Olorus, your son has a natural enthusiasm for letters."

Herodotus appeared anxious, having lost his political status at Halicarnassus, to obtain such status elsewhere. In Athens during this period, the franchise could only be attained with great expense and difficulty. Accordingly, in the spring of the following year Herodotus sailed from Athens with the colonists who went out to found the colony of Thurii, and became a citizen of the new town.

After Herodotus reached the age of 40, there was little further information about him. According to his works, he seems to have made only a few journeys, one to Crotona, one to Metapontum, and one to Athens (about 430 B.C.E.). He may also have composed at Thurii a special work on the history of Assyria, to which he refers twice in his first book, and which is quoted by Aristotle. It has been supposed by many that Herodotus lived to a great age, but indications derived from the later touches added to his work, the sole evidence on the subject, raise doubts about this. None of the changes and additions made to the nine books point to a later date than 424 B.C.E. Since the author promised to make certain changes which were left unfinished, it is assumed that he died at about the age of 60. Ancient sources relate that he died at Thurii, where his tomb was shown in later ages.

Works

Contribution to history

Herodotus recorded much information current about the geography, politics, and history as understoodin his own day. He reported, for example, that the annual flooding of the Nile is said to be the result of melting snows far to the south, and comments that he cannot understand how there can be snow in Africa, the hottest part of the known world. Herodotus' method of comparing all known theories on a subject shows that such hydrological speculation existed in ancient Greece. He also passes on reports from Phoenician sailors that, while circumnavigating Africa, they "saw the sun on the right side while sailing westwards." Thanks to this parenthetical comment, modern scholars have deduced that Africa was likely circumnavigated by ancient seafarers.

At some point, Herodotus became a logios, a reciter of logoi or stories, written in prose. His historical work was originally presented orally, and was created to have an almost theatrical element to it. His subject matter often encompassed battles, other political incidents of note, and, especially, the marvels of foreign lands. He made tours of the Greek cities and the major religious and athletic festivals, where he offered performances in return for payment.

In 431 B.C.E., the Peloponnesian War broke out between Athens and Sparta, and it may have been the this war that inspired Herodotus to collect his stories into a continuous narrative. Centering on the theme of Persia's imperial progress, which only a united Athens and Sparta had managed to resist, his Histories may be seen as a criticism of the war-mongering that threatened to engulf the entire Greek world.

Written between 430 B.C.E. and 425 B.C.E., The Histories were divided by later editors into nine books, named after the nine Muses (the 'Muse of History', Clio, represented the first book). As the work progresses, it becomes apparent that Herodotus is advancing his stated aim to "prevent the great and wonderful actions of the Greeks and the Barbarians from losing their due meed of glory; and to put on record what causes first brought them into conflict." It is only from this perspective that his opening discussion of ancient wife-stealing can be understood; he is attempting to discover who first made the 'west' and the 'east' mutual antagonists, and myth is the only source for information on the subject.

The first six books deal broadly with the growth of the Persian Empire. The tale begins with an account of the first "western" monarch to enter into conflict with an "eastern" people: Croesus of Lydia attacked the Greek city-states of Ionia, and then (misinterpreting a cryptic oracle), also attacked the Persians. As occurred many times throughout The Histories to those who disregarded good advice, Croesus soon lost his kingdom, and nearly his life. Croesus was defeated by Cyrus the Great, founder of the Persian Empire, and Lydia became a Persian province.

The second book forms a lengthy digression concerning the history of Egypt, which Cyrus' successor, Cambyses, annexed to the Empire. The following four books deal with the further growth of the Empire under Darius, the Ionian Revolt, and the burning of Sardis (an act participated in by Athens and at least one other Greek polis). The sixth book describes the very first Persian incursion into Greece, an attack upon those who aided the Ionians and a quest for retribution following the attack upon Sardis, which ended with the defeat of the Persians in 490 B.C.E. at the Battle of Marathon, Greece, near Athens.

The last three books describe the attempt of the Persian king Xerxes to avenge the Persian defeat at Marathon and to finally absorb Greece into the Empire. The Histories ends in the year 479 B.C.E., with the Persian invaders having suffered both a crushing naval defeat at Salamis, and near annihilation of their ground forces at Plataea. The Persian Empire thus receded to the Aegean coastline of Asia Minor, still threatening but much chastened.

It is possible to see the dialectic theme of Persian power and its various excesses running like a thread throughout the narrative—cause and effect, hubris and fate, vengeance and violence. Even the strange and fantastic tales that are liberally sprinkled throughout the text reflect this theme. At every stage, a Persian monarch crosses a body of water or other liminal space and suffers the consequences: Cyrus attacks the Massagetae on the eastern bank of a river, and ends up decapitated; Cambyses attacks the Ethiopians to the south of Egypt, across the desert, and goes mad; Darius attacks the Scythians to the north and is flung back across the Danube; Xerxes lashes and then bridges the Hellespont, and his forces are crushed by the Greeks. Though Herodotus strays off of this main course, he always returns to the question of how and why the Greeks and Persians entered into the greatest conflict then known, and what the consequences were.

Criticism of His works

Herodotus has earned the twin titles The Father of History and The Father of Lies. Dating at least from the time of Cicero's 'On the Laws' (Book 1, Chapter 5), there has been a debate concerning the veracity of his tales, and, more importantly, concerning the extent to which he knew himself to be creating fabrications. Herodotus is perceived in many lights, from being devious and conscious of his fictions, to being gullible and misled by his sources.

There are many cases in which Herodotus, either uncertain of the truth of an event or unimpressed by the questionable "facts" presented to him, reports several prominent accounts of a given subject and then explains which one he believes is the most probable. The Histories were often criticized in antiquity for bias, inaccuracy, and even plagiarism; Lucian of Samosata attacked Herodotus as a liar in Verae historiae and denied him a place among the famous on the Island of the Blessed. Many modern historians and philosophers see his methodology in a more positive light, as a pioneer of relatively objective historical writing based on source materials. Some, however, argue that Herodotus exaggerated the extent of his travels and completely fabricated sources.

Discoveries made since the end of the nineteenth century have helped to rehabilitate Herodotus' reputation. The archaeological study of the now submerged ancient Egyptian city of Heraklion and the recovery of the so-called Naucratis stela lend substantial credence to Herodotus' previously unsupported claim that Heraklion was founded during the Egyptian New Kingdom. Because of growing respect for his accuracy, as well as the his personal observations, Herodotus is now recognized as a pioneer not only in history, but in ethnography and anthropology.

Legacy

Herodotus, like all ancient Greek writers and poets, composed his work in the shadow of Homer. Like Homer, Herodotus presents the Greek foe, in his case the Persian invaders, objectively and without the querulous abuse ancient chroniclers would typically employ to define the enemy. Herodotus' long digressions from the story line also had warrant in Homer. But unlike his great predecessor, Herodotus wrote in prose and was not looking to the legendary past but, in many cases, to events within living memory, even apparently interviewing survivors of the Battle of Marathon.

To later readers Herodotus may appear naively subjective, too ready to entertain, and unreliable as an objective historian.The British historian Thomas Macaulay says Herodotus "tells his story like a slovenly witness, who, heated by partialities and prejudices, unacquainted with the established rules of evidence, and uninstructed as to the obligations of his oath, confounds what he imagines with what he has seen and heard, and brings out facts, reports, conjectures, and fancies in one mass." But such judgments ironically a testify to the methodology he largely invented. Just as ancient Greek thinkers developed a systematic natural philosophy based on speculative indivisible "atoms," laying a foundation for the scientific method, Herodotus formulated a rational approach to the study of the past that later historians would refine through standards of scholarship and evidence into the modern academic discipline of history. Despite his colorful distractions and informality of style, Herodotus remains the authority for the great Persian War, the primary source of even the most skeptical of modern historians.

As a writer of vivid and picturesque prose, Herodotus laid the foundations of the historical narrative and was hailed as a major writer in the ancient world. "O that I were in a condition," says Lucian, "to resemble Herodotus, if only in some measure! I by no means say in all his gifts, but only in some single point; as, for instance, the beauty of his language, or its harmony, or the natural and peculiar grace of the Ionic dialect, or his fulness of thought, or by whatever name those thousand beauties are called which to the despair of his imitator are united in him." Cicero calls his style "copious and polished," Quintilian, "sweet, pure and flowing." Longinus described Herodotus as "the most Homeric of historians," while Dionysius, his countryman, prefers him to Thucydides, and regards him as combining in an extraordinary degree the excellences of sublimity, beauty and the true historical method of composition.

Because of Herodotus, history became not just an arcane subject but a popular form of literature, with the greatest modern historians and nonfiction writers, from Edward Gibbon to David McCulloch, indebted to the Greek "father of history" both for his critical interest in the past and scrupulous literary craftsmanship.

See also

- Thucydides, ancient Greek historian who is often said to be "the father of history"

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

Primary sources

- Several English translations of The Histories of Herodotus are readily available in multiple editions. The most readily available are those translated by:

- Godley, A. D., 1920; revised 1926. Reprinted 1931, 1946, 1960, 1966, 1975, 1981, 1990, 1996, 1999, 2004. Available in four volumes from Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674991303 Printed with Greek on the left and English on the right.

- de Sélincourt, Aubrey, originally 1954; revised by John Marincola in 1972. Several editions from Penguin Books are available.

- Grene, David, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1985.

- George Rawlinson, translation 1858–1860. Public domain; many editions available, although Everyman Library and Wordsworth Classics editions are the most common ones still in print.

- Robin Waterfield, Oxford World's Classics, 1998.

Secondary sources

- Bakker, Egbert E.A. (eds.), Brill's Companion to Herodotus. Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers, 2002. ISBN 9004120602

- Evans, J. A. S., Herodotus: Explorer of the Past: Three Essays. Princeton University Pr, 1991. ISBN 0691068712

- Fehling, Detlev. Herodotus and His "Sources": Citation, Invention, and Narrative Art, Translated by J.G. Howie. Arca Classical and Medieval Texts, Papers, and Monographs, 21. Leeds, UK: Francis Cairns, 1989. ISBN 0905205707

- Flory, Stewart, The Archaic Smile of Herodotus. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1987. ISBN 0814318274

- Hartog, F., The Mirror of Herodotus. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1988. ISBN 0520054873

- Lateiner, D., The Historical Method of Herodotus. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1989. ISBN 0802057934

- Macaulay, Thomas Babington, "The Task Of The Modern Historian."[1]Retrieved May 7, 2008

- Momigliano, A., The Classical Foundations of Modern Historiography. University of California Press, 1992. ISBN 0520078705

- Pritchett, W. K., The Liar School of Herodotus. Amsterdam: Gieben, 1991.

- Thomas, R., Herodotus in Context: ethnography, science and the art of persuasion. Oxford University Press, 2000; New Ed., 2002. ISBN 0521012414

- Internet Ancient History Sourcebook "Herodotus of Helicarnassus"[2] retrieved May 2, 2008

External links

All links retrieved July 16, 2024.

- A reconstructed portrait of Herodotos, based on historical sources, in a contemporary style.

Online translations

- Herodotus Inquiries—new translation with extensive photographic essays of the places and artifacts mentioned by Herodotus hyper-linked to the text

- Project Gutenberg, Herodotus, e-text

- The History of Herodotus at The Internet Classics Archive (translation by George Rawlinson)

- Parallel Greek and English text of the History of Herodotus at the Internet Sacred Text Archive

- Herodotus e-text on Perseus

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.