Merv

| State Historical and Cultural Park "Ancient Merv"* | |

|---|---|

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

| |

| State Party | |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | ii, iii |

| Reference | 886 |

| Region** | Asia-Pacific |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 1999Â (23rd Session) |

| * Name as inscribed on World Heritage List. ** Region as classified by UNESCO. | |

Merv (Russian: ĐĐ”ŃĐČ, from Persian: Ù Ű±Ù, Marv, sometimes transliterated Marw or Mary; cf. Chinese: æšéčż, Mulu), was a major oasis-city in Central Asia, located near the modern day city of Mary, Turkmenistan.

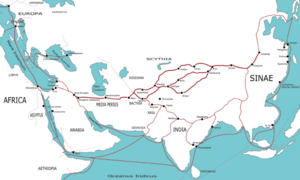

Merv occupied a crucial position near the entrance into Afghanistan on the northwest, and acted as a stepping stone between northeast Persia and the states of Bukhara and Samarkand. It is the oldest and most completely preserved of the oasis cities along the Silk Road, with remains spanning some 4,000 years of human history. Several cities have existed on this site, which is significant for the interchange of culture and politics at a site of major strategic value.

In 1999, UNESCO listed Ancient Merv as a cultural World Heritage Site, noting that "the cities of the Merv oasis have exerted considerable influence over the civilizations of Central Asia and Iran for four millennia."

Geography

The Murghab River rises in northwestern Afghanistan and runs northwest to the Karakum Desert in Turkmenistan. On the river's southern edge, about 230Â miles (370Â km) north of Herat, and 280Â miles (450Â km) south of Khiva lies the oasis of Merv. Its area is about 1,900Â square miles (4,900Â kmÂČ). The great chain of mountains which, under the names of Paropamisade and Hindu Kush, extends from the Caspian Sea to the Pamir Mountains is interrupted some 180Â miles (290Â km) south of Merv. Through or near this gap flow northwards in parallel courses the Tejen and Murgab rivers, until they lose themselves in the Karakum Desert.

Situated in the inland delta of the Murghab River, gives Merv two distinct advantages: first, it provides an easy southeast-northwest route from the Afghan highlands towards the lowlands of Karakum, the Amu Darya valley and Khwarezm. Second, the Murgab delta, being a large well-watered zone in the midst of the dry Karakum, serves as a natural stopping-point for the routes from northwest Iran towards Transoxianaâthe Silk Roads. The delta, and thus Merv, lies at the junction of these two important routes: the northwest-southeast route to Herat and Balkh (and thus to the Indus and beyond) and the southwest-northeast route from Tus and Nishapur to Bukhara and Samarkand.

Thus Merv sits as a sort of watch tower over the entrance into Afghanistan on the northwest and at the same time create a stepping-stone or Ă©tape between northeast Persia and the states of Bukhara and Samarkand.

Merv is dry and hot in summer and cold in winter. The heat of summer is oppressive. The wind raises clouds of fine dust which fill the air, rendering it opaque, almost obscuring the noonday sun, making breathing difficult. In winter the climate is pleasant. Snow rarely falls, and when it does, it melts almost immediately. The annual rainfall rarely exceeds five inches, and there is often no rain from June until October. In the summer, temperatures can reach 45°C (113°F), in winter it they can be as low as -7°C (19.4°F). The average yearly temperature is 16°C (60.8).

History

Merv's origins are prehistoric: archaeological surveys have revealed evidence of village life as far back as the 3rd millennium B.C.E.

Under the name of Mouru, Merv is mentioned with Bakhdi (Balkh) in the geography of the Zend-Avesta (Avesta being the primary collection of sacred texts of Zoroastrianism, Zend being Middle Persian commentaries on them). Under the Achaemenid Dynasty Merv is mentioned as being a place of some importance: under the name of Margu it occurs as part of one of the satrapies in the Behistun inscriptions (ca 515 B.C.E.) of the Persian monarch Darius Hystaspis. The ancient city appears to have been re-founded by Cyrus the Great (559 - 530 B.C.E.), but the Achaemenid levels are deeply covered by later strata at the site.

Alexander the Great's visit to Merv is merely legendary, but the city was named "Alexandria" for a time. After Alexander's death, Merv became the chief city of the province of Margiana of the Seleucid, Parthian and Sassanid states. Merv was re-named âAntiochia Margiana,â by the Seleucid ruler Antiochus Soter, who rebuilt and expanded the city at the site presently known as Gyaur Gala.

Han Dynasty General Ban Chao led an entirely mounted infantry and light cavalry of 70,000 men through Merv in the year 97 C.E. as part of a military expedition against barbarians harassing the trade routes that are now popularly known as the Silk Road. This resulted in a large exodus of some ancient Xiongnu tribes that migrated further west into European proper; their close descendants becoming known as the Huns, of whom, Atilla was the most well-known.

After the Sassanid Ardashir I (220-240 C.E.) took Merv, the study of numismatics picks up the thread: a long unbroken direct Sassanian rule of four centuries is documented from the unbroken series of coins originally minted at Merv. During this period Merv was home to practitioners of a wide range of different religions beside the official Zoroastrianism of the Sassanids, including many Buddhists, Manichaeans, and Nestorian Christians. During the fifth century C.E., Merv was the seat of a major archbishopric of the Nestorian Church.

Arab occupation and influence

Sassanian rule came to an end when the last Sassanian ruler, Yazdegard III (632-651) was murdered not far from the city and the Sassanian military governor surrendered to the approaching Arab army. The city was occupied by lieutenants of the caliph Uthman ibn Affan, and became the capital of the Umayyad province of Khorasan. Using this city as their base, Arabs led by Qutaibah bin Muslim, brought under subjection large parts of Central Asia, including Balkh, Bukhara, Fergana and Kashgaria, and penetrated into China as far as the province of Gansu early in the eighth century. Merv, and Khorasan in general was to become one of the first parts of the Persian-speaking world to become majority-Muslim. Arab immigration to the area was substantial.

Merv reached renewed importance in February of 748 when the Iranian general Abu Muslim (d. 750) declared a new Abbasid dynasty at Merv, expanding and re-founding the city, and, in the name of the Abbasid line, used the city as a base of rebellion against the Umayyad caliphate. After the Abbasids were established in Baghdad, Abu Muslim continued to rule Merv as a semi-independent prince until his eventual assassination. Indeed, Merv was the center of Abbasid partisanship for the duration of the Abbasid revolution, and later on became a consistent source of political support for the Abbasid rulers in Baghdad, and the governorship of Khurasan at Merv was considered one of the most important political figures of the Caliphate. The influential Barmakid family was based in Merv and played an important part in transferring Greek knowledge into the Arab world.

Throughout the Abbasid era, Merv remained the capital and most important city of Khurasan. During this time, the Arab historian Al-Muqaddasi called Merv âdelightful, fine, elegant, brilliant, extensive, and pleasant.â Merv's architecture perhaps provided the inspiration for the Abbasid re-planning of Baghdad. The city was notable for being a home for immigrants from the Arab lands as well as from Sogdia and elsewhere in Central Asia. Merv's importance to the Abbasids was highlighted in the period from 813 to 818 when the temporary residency of the caliph al-Ma'mun effectively made Merv the capital of the Muslim world. Merv was also the center of a major eighth-century Neo-Mazdakite movement led by al-Muqanna, the âVeiled Prophet,â who gained many followers by claiming to be an incarnation of God and heir to 'Ali and Abu Muslim; the Khurramiyya inspired by him persisted in Merv until the twelfth century.

During this period Merv, like Samarkand and Bukhara, was one of the great cities of Muslim scholarship; the celebrated historian Yaqut studied in its libraries. Merv produced a number of scholars in various branches of knowledge, such as Islamic law, hadith, history, and literature. Several scholars have the name Marwazi ۧÙÙ Ű±ÙŰČÙ designating them as hailing from Merv, including the famous Ahmad Ibn Hanbal. The city continued to have a substantial Christian community. In 1009 the Archbishop of Merv sent a letter to the Patriarch at Baghdad asking that the Keraits be allowed to fast less than other Nestorian Christians.[1]

As the caliphate weakened, Arab rule in Merv was replaced by that of the Persian general Tahir b. al -Husayn and his Tahirid dynasty in 821. The Tahirids were in turn replaced in Merv by the Samanids and then the Ghaznavids.

Turk and Mongol control

In 1037, the Seljuks, a clan of Oghuz Turks moving from the steppes east of the Aral Sea, peacefully took over Merv under the leadership of Toghril Begâthe Ghaznavid sultan Masud was extremely unpopular in the city. Togrul's brother Ăagry stayed in Merv as the Seljuk domains grew to include the rest of Khurasan and Iran, and it subsequently became a favorite city of the Seljuk leadership. Alp Arslan, the second sultan of the Seljuk dynasty and great-grandson of Seljuk, and Sultan Sanjar were both buried at Merv.

It was during this period that Merv expanded to its greatest sizeâArab and Persian geographers termed it âthe mother of the world,â the ârendezvous of great and small,â the âchief city of Khurasanâ and the capital of the eastern Islamic world. Written sources also attest to a large library and madrasa founded by Nizam al-Mulk, as well as many other major cultural institutions. Merv was also said to have a market that was âthe best of the major cities of Iran and Khurasanâ (Herrmann. 1999). It is believed that Merv was the largest city in the world from 1145 to 1153, with a population of 200,000.[2]

Sanjar's rule, marked by conflict with the Kara-Khitai and Khwarazmians, ended in 1153 when the Turkish Ghuzz nomads from beyond the Amu Darya pillaged the city. Subsequently Merv changed hands between the Khwarazmians of Khiva, the Ghuzz, and the Ghurids, and began to lose importance relative to Khurasan's other major city, Nishapur.

In 1221, Merv opened its gates to Tule, son of Genghis Khan, chief of the Mongols, on which occasion most of the inhabitants are said to have been butchered. The Persian historian Juvayni, writing a generation after the destruction of Merv, wrote

- âThe Mongols ordered that, apart from four hundred artisans. .., the whole population, including the women and children, should be killed, and no one, whether woman or man, be spared. To each [Mongol soldier] was allotted the execution of three or four hundred Persians. So many had been killed by nightfall that the mountains became hillocks, and the plain was soaked with the blood of the mighty.â[3]

Some historians believe that over one million people died in the aftermath of the city's capture, including hundreds of thousands of refugees from elsewhere, making it one of the bloodiest captures of a city in world history.

Excavations revealed drastic rebuilding of the city's fortifications in the aftermath, but the prosperity of the city was over. The Mongol invasion was to spell the end for Merv and indeed other major centers for more than a century. In the early part of the fourteenth century, the town was made the seat of a Christian archbishopric of the Eastern Church. On the death of the grandson of Genghis Khan, Merv was included (1380) in the possessions of Timur, Turco-Persian prince of Samarkand.

In 1505, the city was occupied by the Uzbeks, who five years later were expelled by Shah Ismail, the founder of the Safavid dynasty of Persia. It was in this period that a large dam (the 'Soltanbent') on the river Murghab was restored by a Persian nobleman, and the settlement which grew up in the area thus irrigated became known as 'BaĂœramaly', by which name it is referred to in some nineteenth century texts. Merv remained in the hands of Persia until 1787, when it was captured by the Emir of Bokhara. Seven years later, the Bukharans razed the city to the ground, broke down the dams, and converted the district into a waste. The entire population of the city and the surrounding area of about 100,000 were then deported in several stages to the Bukharan oasis. Being nearly all Persian-speaking Shi'as, they resisted assimilation into the Sunni population of Bukhara, although they spoke the same language. These Marvis survive today, and were listed as "Iranis/Iranians" in Soviet censuses through the 1980s, and locate them in Samarkand as well as Bukhara and the area in between on the Zarafshan river.

When Sir Alexander Burnes traversed the country in 1832, the Khivans were the rulers of Merv. About this time, the Tekke Turkomans, then living on the Tejen River, were forced by the Persians to migrate northward. The Khivans contested the advance of the Tekkes, but ultimately, about 1856, the latter became the sovereign power in the country, and remained so until the Russians occupied the oasis in 1883. The arrival of Russians triggered the Pendi Incident of the Great Game between the British Empire and Imperial Russia.

Remains

Organization of Remains

Merv consists of a few discrete walled cities very near each other, each of which was constructed on uninhabited land by builders of different eras, used, and then abandoned and never rebuilt. Four walled cities correspond to the chief periods of Merv's importance: the oldest, Erkgala, corresponds to Achaemenid Merv, and is the smallest of the three. GĂ€wĂŒrgala, which surrounds Erkgala, comprises the Hellenistic and Sassanian metropolis and also served as an industrial suburb to the Abbasid/Seljuk city, Soltangalaâby far the largest of the three. The smaller Timurid city was founded a short distance to the south and is now called Abdyllahangala. Various other ancient buildings are scattered between and around these four cities; all of the sites are preserved in the âAncient Merv Archaeological Parkâ just north of the modern village of BaĂœramaly and 30 kilometers west of the large Soviet-built city of Mary.

GĂ€wĂŒrgala

GĂ€wĂŒrgala's most visible remaining structures are its defensive installations. Three walls, one built atop the next, are in evidence. A Seleucid wall, graduated in the interior and straight on the exterior, forms a platform for the second, larger wall, built of mudbricks and stepped on the interior. The form of this wall is similar to other Hellenistic fortresses found in Anatolia, though this wall is unique for being made of mud-brick instead of stone. The third wall is possibly Sassanian and is built of larger bricks (Williams. 2002). Surrounding the wall was a variety of pottery sherds, particularly Parthian ones. The size of these fortifications are evidence of Merv's importance during the pre-Islamic era; no pre-Islamic fortifications of comparable size have been found anywhere in the Karakum. GĂ€wĂŒrgala is also important for the vast amount of numismatic data that it has revealed; an unbroken series of Sassanian coins has been found there, hinting at the extraordinary political stability of this period.

Even after the foundation of Soltangala by Abu Muslim at the start of the Abbasid dynasty, GĂ€wĂŒrgala persisted as a suburb of the larger Soltangala. In GĂ€wĂŒrgala are concentrated many Abbasid-era âindustrialâ buildings: pottery kilns, steel, iron, and copper-working workshops, and so on. A well-preserved pottery kiln has an intact vaulted arch support and a square firepit. GĂ€wĂŒrgala seems to have been the craftsmens' quarters throughout the Abbasid and pre-Seljuk periods.[4]

Soltangala

Soltangala is by far the largest of Merv's cities. Textual sources establish that it was Abu Muslim, the leader of the Abbasid rebellion, who symbolized the beginning of the new Caliphate by commissioning monumental structures to the west of the GĂ€wĂŒrgala walls, in what then became Soltangala.[4] The area was quickly walled and became the core of medieval Merv; centuries of prosperity which followed are attested to by the many Abbasid-era köshks discovered in and outside of Soltangala. KöĆks, which comprise the chief remains of Abbasid Merv, are a building type unique to Central Asia during this period. A kind of semi-fortified two-story palace whose corrugated walls give it a unique and striking appearance, köshks were the residences of Merv's elite. The second story of these structures comprised living quarters; the first story may have been used for storage. Parapets lined the roof, which was often used for living quarters as well. Merv's largest and best-preserved Abbasid köĆk is the Greater Gyzgala, located just outside the Soltangala's western wall; this structure consisted of 17 rooms surrounding a central courtyard. The nearby Lesser Gyzgala had extraordinarily thick walls with deep corrugations, as well as multiple interior stairways leading to second-story living quarters. All of Merv's köĆks are in precarious states of preservation.[4]

However, the most important of Soltangala's surviving buildings are Seljuk constructions. In the eleventh century C.E., the nomadic Oghuz Turks, formerly vassals of the Khwarazmshah in the northern steppes, began to move southward under the leadership of the Seljuk clan and its ruler Togrul Beg. Togrul's conquest of Merv in 1037 revitalized the city; under his descendants, especially Sanjar, who made it his residence, Merv found itself at the center of a large multicultural empire.

Evidence of this prosperity is found throughout the Soltangala. Many of these are concentrated in Soltangala's citadel, the Shahryar Ark, located on its east side. In the center of the Sharhryar Ark is located the Seljuk palace probably built by Sanjar. The surviving mud brick walls lead to the conclusion that this palace, relatively small, was composed of tall single-story rooms surrounding a central court along with four axial iwans at the entrance to each side. Low areas nearby seem to indicate a large garden which included an artificial lake; similar gardens were found in other Central Asian palaces. Unfortunately, any remnants of interior or exterior decoration have been lost due to erosion or theft.

Another notable Seljuk structure within the Shahryar Ark is the kepderihana, or âpigeon house.â This mysterious building, among the best-preserved in the whole Merv oasis, comprises one long and narrow windowless room with many tiers of niches across the walls. It is believed by some [sources] that the kepter khana (there are more elsewhere in Merv and Central Asia) was indeed a pigeon roost used to raise pigeons, in order to collect their dung which is used in growing the melons for which Merv was famous. Others, just as justifiably (Herrmann 1999), see the kepderihanas as libraries or treasuries, due to their location in high status areas next to important structures.

The best-preserved of all the structures in Merv is the twelfth-century mausoleum of Sultan Sanjar. It is the largest of Seljuk mausoleums and is also the first dated mosque-mausoleum complex, a form which was later to become common. It is square, 27Â meters (89Â ft) per side, with two entrances on opposite sides; a large central dome supported by an octagonal system of ribs and arches covers the interior (Ettinghausen). The dome's exterior was turquoise and its height made it quite imposing; it was said that approaching caravans could see the mausoleum while still a day's march from the city. The mausoleum's decoration, in typical early Seljuk style, was conservative, with interior stucco work and geometric brick decoration, now mainly lost, on the outside (Ettinghausen). With the exception of the exterior decoration, the mausoleum is largely intact.

A final set of Seljuk remains are the walls of the Soltangala. These fortifications, which in large part still remain, began as 8â9 meters (26â30Â ft) high mud brick structures, inside of which were chambers from which to shoot arrows. There were horseshoe-shaped towers every 15â35 meters (49â110Â ft). These walls, however, did not prove to be effective because they were not of adequate thickness to withstand catapults and other artillery. By the mid-twelfth century, the galleries were filled in and the wall was greatly strengthened. A secondary, smaller wall was built in front of the Soltangala's main wall, and finally the medieval city's suburbsâknown today as Isgendergalaâwere enclosed by a 5Â meters (16Â ft) thick wall. The three walls sufficed to hold off the Mongol army for at least one of its offensives, before ultimately succumbing in 1221.

Many ceramics have also been recovered from the Abbasid and Seljuk eras, primarily from GĂ€wĂŒrgala, the city walls of Soltangala, and the Shahryar Ark. The GĂ€wĂŒrgala ware was primarily late Abbasid, and it consisted primarily of red slip-painted bowls with geometric designs. The pottery recovered from the Soltangala walls is dominated by eleventh-twelfth century color-splashed yellow and green pottery, similar to contemporary styles common in Nishapur. Turquoise and black bowls were discovered in the Shahryar Ark palace, as well as an interesting deposit of Mongol-style pottery, perhaps related to the city's unsuccessful re-foundation under the Il-khans. Also from this era is a ceramic mask used for decorating walls found among the ruins of what is believedânot without controversyâto be a Mongol-built Buddhist temple in the southern suburbs of Soltangala.

Preservation

The archaeological sites at Merv have been relatively untouched, making their authenticity irreproachable. Some exploratory excavations were conducted in 1885 by the Russian general A.V. Komarov, the governor of the Transcaspian oblast.[5] The first fully professional dig was directed by Valentin Alekseevich Zhukovsky of the Imperial Archaeological Commission, in 1890 and published in 1894.[6] The American Carnegie Institute's excavations were under the direction of a geologist, Raphael Pumpelly, and a German archaeologist, Hubert Schmidt.

Merv is covered by the provisions of Turkmenistan's 1992 Law on the Protection of Turkmenistan Historical and Cultural Monuments. The State Historical and Cultural Park âAncient Mervâ was created by decree in 1997. All interventions, including archaeological excavations, within the Park require official permits from the Ministry of Culture.[7]

Merv is currently the focus of the Ancient Merv Project. From 1992 to 2000, a joint team of archaeologists from Turkmenistan and the United Kingdom have made remarkable discoveries. In 2001, a collaboration was begun between the Institute of Archaeology, University College London and the Turkmen authorities. [8] The project is concerned with the complex conservation and management issues posed by the site as well as furthering historical understanding.

In 1999, Merv was listed by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site based upon the considerable influence it exerted over the Central Asia and Iran. This was especially evident during the Seljuk era in the areas of architecture and architectural decoration, and scientific and cultural development. UNESCO noted that "the sequence of the cities of the Merv oasis, their fortifications, and their urban lay-outs bear exceptional testimony to the civilizations of Central Asia over several millennia."[9]

Notes

- â Columba Cary-Elwes. 1957. China and the cross; a survey of missionary history. New York: P.J. Kenedy.

- â Matt T. Rosenberg. Largest Cities Through History The New York Times Company. Retrieved January 18, 2009.

- â JuvaynÄ«, Ê»AlÄÊŒ al-DÄ«n Ê»AáčÄ Malik, John Andrew Boyle, and David Morgan. 1997. Genghis Khan: the history of the world conqueror. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 9780295976549

- â 4.0 4.1 4.2 Herrmann. 1999.

- â Fredrik T. Hiebert; K. Kurbansakhatov, and Hubert Schmidt. 2003. A Central Asian village at the dawn of civilization, excavations at Anau, Turkmenistan. University Museum monograph, 116. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. ISBN 9781931707503

- â V.A. Zhukovsky, 1894. Razvalinii starogo Merva. St Peterburg.

- â UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Advisory Body Evaluation Retrieved January 18, 2009.

- â Institute of Archaeology, University College London. Welcome to Ancient Merv Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- â UNESCO World Heritage Centre. State Historical and Cultural Park "Ancient Merv" Retrieved January 17, 2009.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Babakov, Horace, and Gabriele Rossi-Osmida. 2002. Margiana: Gonur-depe necropolis : 10 years of excavations by Ligabue Study and Research Centre. [Padova]: Il Punto. ISBN 9788888386027

- Ettinghausen, Richard, Oleg Grabar, and Marilyn Jenkins. 2001. Islamic art and architecture 650-1250. Yale University Press Pelican history of art. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300088694

- Herrmann, Georgina. 1999. Monuments of Merv: traditional buildings of the Karakum. London: Soc. of Antiquaries of London. ISBN 9780854312757

- Institute of Archaeology, University College London. Welcome to Ancient Merv Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- Internet Archaeology. The landscapes of Islamic Merv, Turkmenistan: Where to draw the line? Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- Sarianidi, V. 1994. "Temples of Bronze Age Margiana." ANTIQUITY -OXFORD-. 68 (259): 388. OCLC 202694359

- Williams, Tim, and Kakamurad Kurbansakhatov. 2003. "The Ancient Merv Project. Turkmenistan. Preliminary Report on the Second Season (2002)." Iran : Journal of the British Institute of Persian Studies. 41: 139. OCLC 98418958

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. State Historical and Cultural Park "Ancient Merv" Retrieved January 17, 2009.

Coordinates:

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.