Bukhara

| Bukhara Buxoro / –Ď—É—Ö–ĺ—Ä–ĺ / ō®ōģōßōĪōß |

|

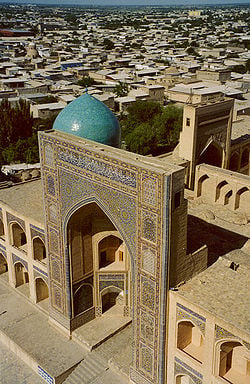

| Mir-i Arab madrasah | |

| Location in Uzbekistan | |

| Coordinates: 39¬į46‚Ä≤N 64¬į26‚Ä≤E | |

|---|---|

| Country | |

| Province | Bukhara Province |

| Government | |

|  - Hokim | Rustamov Qiyomiddin Qahhorovich |

| Population (2009) | |

|  - City | 263,400 |

|  - Urban | 283,400 |

|  - Metro | 328,400 |

| Time zone | GMT +5 (UTC+5) |

| Postcode | 2001–•–• |

| Area code(s) | local 365, int. +99865 |

| Website: http://www.buxoro.uz/ | |

Bukhara (Uzbek: Buxoro, Tajik: –Ď—É—Ö–ĺ—Ä–ĺ, Persian: ō®ŔŹōģōßōĪōß, Russian: –Ď—É—Ö–į—Ä–į), also spelled as Bukhoro and Bokhara, from the Soghdian ő≤uxńĀrak ("lucky place"), is the capital of the Bukhara Province of Uzbekistan, and the nation's fifth-largest city.

The region around Bukhara has been inhabited for at least five millennia and the city itself has existed for half that time. Located on the Silk Road, the city has long been a center of trade, scholarship, culture, and religion. It attained its greatest importance in the late sixteenth century, when the ShaybńĀnids‚Äô possessions included most of Central Asia as well as northern Persia and Afghanistan. Education courses during this period included theological sciences, mathematics, jurisprudence, logic, music, and poetry. This system had a positive influence upon development and wide circulation of the Uzbek language, as well as on the development of literature, science, art and technical skills. Famous poets, theologians, and physicians flocked to the city. The city remained well-known and influential through the nineteenth century, playing a significant part in cultural and religious life of the region.

There are numerous historical and architectural monuments in and around the city and adjacent districts, and a large number of seventeenth century madrasas. Most notable is the famous tomb of Ismail Samani (also known as as the Royal Mausoleum of the SńĀmńĀnids), considered a masterpiece of early funerary architecture.

Its old city section, which was made a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1993, is famous as a "living museum" and a center for international tourism. It is the most complete example of a medieval city in Central Asia, with an urban fabric that has remained largely intact.

Geography

About 140 miles (225km) west of Samarkand in south-central Uzbekistan, Bukhara is located on the Zeravshan River, at an elevation of 751 feet (229 meters).

Bukhara has a typically arid continental climate. The average maximum daytime temperature in January is 46¬įF (8¬įC), rising to an average maximum of around 100¬įF (37.8¬įC) in July. Mean annual precipitation is 22.8 inches (580 mm).

The water was important in the hot, dry climate of Central Asia, so from ancient times, irrigation farming was developed. Cities were built near rivers and water channels were built to serve the entire city. Uncovered reservoirs, known as hauzes, were constructed. Special covered water reservoirs, or sardobas, were built along caravan routes to supply travelers and their animals with water.

However, the heavy use of agrochemicals during the era under the Soviet Union, diversion of huge amounts of irrigation water from the two rivers that feed Uzbekistan, and the chronic lack of water treatment plants, have caused health and environmental problems on an enormous scale.

History

Around 3000 B.C.E., an advanced Bronze Age culture called the Sapalli Culture thrived at Varakhsha, Vardan, Paykend, and Ramitan. In 1500 B.C.E., a drying climate, iron technology, and the arrival of Aryan nomads triggered a population shift to the Bukhara oasis from outlying areas. The Sapalli and Aryan people lived in villages along the shores of a dense lake and wetland area in the Zeravshan Fan (the Zeravshan River had ceased draining to the Oxus). By 1000 B.C.E., both groups had merged into a distinctive culture. Around 800 B.C.E., this new culture, called Sogdian, flourished in city-states along the Zeravshan Valley. By this time the lake had silted up and three small fortified settlements had been built. By 500 B.C.E., these settlements had grown together and were enclosed by a wall; thus Bukhara was born.

Bukhara entered history in 500 B.C.E. as vassal state in the Persian Empire. Later it passed into the hands of the Alexander the Great (356-323 B.C.E.), the Hellenistic Seleucid Empire (312-63 B.C.E.), the Greco-Bactrians (250-125 B.C.E.), and the Kushan Empire (105-250 C.E.).

During this time Bukhara functioned as a cult center for the worship of Anahita, and her associated temple economy. Approximately once a lunar cycle, the inhabitants of the Zeravshan Fan exchanged their old idols of the goddess for new ones. The trade festival took place in front of the Mokh Temple. This festival was important in assuring the fertility of land on which all inhabitants of the delta depended.

As a result of the trade festivals, Bukhara became a center of commerce. As trade accelerated along the silk road after the Han Dynasty (206 B.C.E.-220 C.E.) pushed back the northern tribes to secure this key trading route,[1] the already prosperous city of Bukhara then became the logical choice for a market. The silk trade itself created a growth boom in the city which ended around 350 B.C.E. After the fall of the Kushan Empire, Bukhara passed into the hands of Hua tribes from Mongolia and entered a steep decline.

Prior to the Arab invasion in 650 C.E., Bukhara was a stronghold for followers of two persecuted religious movements within the theocratic Sassanian Empire; Manicheanism and Nestorian Christianity.[2] When the Islamic armies arrived in 650 C.E., they found a multi-ethnic, multi-religious and decentralized collection of peoples; nevertheless, after a century many of the subjects of the Caliphate had not converted to Islam, but retained their previous religion.[3] The lack of any central power meant that while the Arabs could gain an easy victory in battle or raiding, they could never hold territory in Central Asia. In fact, Bukhara, along with other cities in the Sogdian federation, played the Caliphate against the Tang Empire. The Arabs did not truly conquer Bukhara until after the Battle of Talas in 751 C.E. Islam became the dominant religion at this time and remains the dominant religion to the present day.

For a century after the Battle of Talas, Islam slowly took root in Bukhara. In 850 C.E., Bukhara became the capital of the Persian Samanid Empire (819-999), which brought about a revival of Iranian language and culture following the period of Arab domination. During the golden age of the Samanids, Bukhara became the intellectual center of the Islamic world and therefore, at that time, of the world itself. Many illustrious scholars penned their treaties here. The most prominent Islamic scholar known as Imam al-Bukhari, who gathered most authentic sayings (hadiths) of Prophet Muhammad, was born in this city. The city was also a center of Sufi Islam, most notably the Naqshbandi Order.

In 999, the Samanids were toppled by the Karakhanid Uyghurs. Later, Bukhara became part of the kingdom of Khwarezm Shahs, who incurred the wrath of the Mongols by killing their ambassador, and in 1220, the city was leveled by Genghis Khan (1162-1227), and captured by Timur (Tamerlane) in 1370.

In 1506, Bukhara was conquered by the Uzbek Shaybanid dynasty, who, from 1533, made it the capital of the Bukhara khanate. Bukhara attained its greatest importance when the Shaybanids, who descended from Shayban (Shiban), the grandson of Genghis Khan, controlled most of Central Asia. Abd al-Aziz-khan (1533-1550) established an extensive library there. The Shaybanids reformed public education by setting up madrassah that provided 21 years of education in which pupils studied theological sciences, arithmetic, jurisprudence, logic, music, and poetry.

Shah of Persia Nadir Shah (1698-1747) conquered the Khanate of Bukhara in 1740, and from the 1750s, the Manń°it family ruled behind the scenes, until the emir Shah Murad declared himself the ruler 1785, establishing the Emirate of Bukhara.

Bukhara entered the modern period as a colonial acquisition of the Russian Empire, and became a pawn in the "Great Game" of territory control between Russia and Britain. In 1868, the emirate was made a Russian protectorate. The Trans-Caspian railway was built through the city in the late 19th century. The last emir, Mohammed Alim Khan (1880-1944), was ousted by the Russian Red Army in September 1920, and fled to Afghanistan.

Bukhara remained the capital of the Bukharan People's Soviet Republic, which existed from 1920 to 1925. Then city was integrated into the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic. When natural gas was discovered nearby in the late 1950s, Bukhara grew rapidly, and remained the capital when Uzbekistan gained independence in 1991.

The historic center of Bukhara was listed by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site in 1993. It contains numerous mosques and madrassas.

Government

Uzbekistan is a republic noted for authoritarian presidential rule, with little power outside the executive branch. Bukhara is the capital of Buxoro province, one of Uzbekistan's 12 provinces, and is divided into 11 administrative districts. Other major towns include Alat, Karakol, Galasiya, Gazly, Gijduvan, Kagan, Romitan, Shavirkan, and Vabkent. Uzbekistan has issues with terrorism by Islamic militants, economic stagnation, and the curtailment, of human rights.

Economy

Uzbekistan is now the world's second-largest cotton exporter and fifth largest producer; it relies heavily on cotton production as the major source of export earnings. Other major export earners include gold, natural gas, and oil. Bukhara is the largest city in a natural gas region.

The province also has petroleum, graphite, bentonite, marble, sulfur, limestone, and raw materials for construction. Industrial activities include oil refining, cotton purification, textiles, Uzbek Ikat and light industry. Traditional Uzbek crafts such as gold embroidery, ceramics, and engraving have been revived. Uzbekistan's per capita GDP was estimated at $2300 in 2007. Tourism also contributes to the local economy.

Demographics

Bukhara recorded a population of 237,900 in the 1999 census. Bukhara (along with Samarkand) is one of the two major centers of Uzbekistan's Tajik minority. Bukhara was also home to the Bukharian Jews, whose ancestors settled in the city during Roman times. Most Bukharian Jews left Bukhara between 1925 and 2000.

Uzbeks were estimated to make up 80 percent of Uzbekistan's population in 1996, Russians 5.5 percent, Tajiks 5 percent, Kazakhs 3 percent, Karakalpaks 2.5 percent, Tatars 1.5 percent, other 2.5 percent. The Uzbek language is spoken by 74.3 percent, Russian 14.2 percent, Tajik 4.4 percent, and other 7.1 percent. Muslims (mostly Sunnis) make up 88 percent of the population, Eastern Orthodox 9 percent, and others 3 percent.

Bukhara State University, founded in 1930, is located there as are medical and light industry institutes.

Society and culture

Many prominent people lived in Bukhara, including Muhammad Ibn Ismail Ibn Ibrahim Ibn al-Mughirah Ibn Bardiziyeh al-Bukhari (810-870); Avicenna (Abu Ali ibn Sina) (980-1037), a physician known for his encyclopedic knowledge; the outstanding historians Balyami and Narshakhi (tenth century); al-Utobi (eleventh century); the illustrious poet Ismatallah Bukhari (1365-1426)¬†; the renowned physician Mualan Abd al-Khakim (sixteenth century); Karri Rakhmatallah Bukhari (died in 1893)‚ÄĒthe specialist in study of literature; and the calligrapher Mirza Abd al-Aziz Bukhari.

Places of interest

| Historic Centre of Bukhara* | |

|---|---|

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

| |

| State Party | |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | ii, iv, vi |

| Reference | 602 |

| Region** | Asia-Pacific |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 1993  (17th Session) |

| * Name as inscribed on World Heritage List. ** Region as classified by UNESCO. | |

Famous as a "living museum," Bukhara has numerous historical and architectural monuments. The Lyab-i Hauz Ensemble (1568-1622) is the name of the area surrounding one of the few remaining hauz (ponds) in the city of Bukhara. Until the Soviet period there were many such ponds, which were the city's principal source of water, but they were notorious for spreading disease and were mostly filled in during the 1920s and 1930s. The Lyab-i Hauz survived because it is the centerpiece of a magnificent architectural ensemble, created during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, which has not been significantly changed since. The Lyab-i Hauz ensemble, surrounding the pond on three sides, consists of the Kukeldash Madrasah (1568-1569), the largest in the city (on the north side of the pont), and of two religious edifices built by Nadir Divan-Beghi: A khanaka (1620), or lodging-house for itinerant Sufis, and a madrasah (1622) that stand on the west and east sides of the pond respectively.[4]

The Ark, the city fortress, is the oldest structure in Bukhara. Other buildings and sites of interest include:

- The Ismail Samani mausoleum, which was built between 892 and 943 as the resting-place of Ismail Samani (d. 907), the founder of the Samanid dynasty, which was the last Persian dynasty to rule in Central Asia, is one of the most esteemed sights of Central Asian architecture.

- The Kalyan minaret, which was built in 1127, was made in the form of a circular-pillar brick tower, narrowing upwards, of 29.53 feet (nine meters) diameter at the bottom, 19.69 feet (six meters) overhead and 149.61 feet (45.6 meters) high.

- The Kalyan Mosque, believed to have been completed in 1514, is equal with Bibi-Khanym Mosque in Samarkand in size. Although they are of the same type of building, they are absolutely different in terms of art of building.

- Other madrassahs include the UlŇęgh Beg Madrassah, built in 1417, and the Mir-i Arab Madrassah, built in 1536, and the Abd al- ŅAziz KhńĀn Madrassah, built in 1652.

- The Chashma-Ayub, which is located near the Samani mausoleum, is a well, the water of which is still pure and is considered to have healing properties. Its name means Job's well due to the legend according to which Job (Ayub) visited this place and made a well by the blow of his staff. The current building was constructed during the reign of Timur and features a Khwarezm-style conical dome uncommon in Bukhara.

Looking to the future

Uzbekistan struggles with terrorism perpetrated by Islamic militants, economic stagnation, and the curtailment of human rights. This undoubtedly affects the city.

Bukhara's history as a major city on the Silk Road, and its position as a center of trade, scholarship, culture, and religion remains evident through the character of its urban fabric, which has remained largely intact. Its status as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and its numerous historical and architectural monuments could attract a steady flow of international visitors each year, a potential goldmine for the city's economy.

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ C. Michael Hogan, November 19, 2007, Silk Road, North China, The Megalithic Portal. Retrieved October 13, 2008.

- ‚ÜĎ Mark Dickens, Nestorian Christianity in Central Asia, Oxus Communications. Retrieved October 13, 2008.

- ‚ÜĎ Josef W. Meri, Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia (Taylor & Francis, ISBN 0415966914).

- ‚ÜĎ Dimitriy Page, Bukhara‚ÄĒthe center of enlightenment in the East. Retrieved October 11, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Allworth, Edward. 1990. The Modern Uzbeks: From the Fourteenth Century to the Present: A Cultural History. Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Press, Stanford University. ISBN 0817987312.

- Dimitriy, Page. January 14, 2007. Bukhara‚ÄĒthe center of enlightenment in the East. pagetour.org. Retrieved October 11, 2008.

- Moorcroft, William, and George Trebeck. 1841. Travels in the Himalayan Provinces of Hindustan and the Panjab, in Ladakh and Kashmir, in Peshawar, Kabul, Kunduz, and Bokhara: From 1819 to 1825. London: J. Murray. OCLC 26490473.

- Paksoy, H. B. 1992. Central Asian Monuments. Beylerbeyi, Istanbul: Isis Press. ISBN 9789754280333.

- Rall, Ted. 2006. Silk Road to Ruin: Is Central Asia the new Middle East? New York: NBM. ISBN 1561634549.

- World Fact Book. 2008. Uzbekistan.

External links

All links retrieved November 22, 2023.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.