Sogdiana

Sogdiana, ca. 300 B.C.E. | |

| Languages | Sogdian language |

|---|---|

| Religions | Buddhism, Zoroastrianism |

| Capitals | Samarkand, Bukhara, Khujand, Kesh |

| Area | Between the Amu Darya and the Syr Darya |

| Existed | |

Sogdiana or Sogdia (Tajik: –°—É“ď–ī - Old Persian: Sughuda; Persian: ō≥ōļōĮ; Chinese: Á≤üÁČĻ - S√Ļt√®) was the ancient civilization of an Iranian people and a province of the Achaemenid Persian Empire, the eighteenth in the list in the Behistun Inscription of Darius the Great (i. 16). Sogdiana is "listed" as the second 'good lands and countries' that Ahura Mazda created. This region is listed after the first, Airyana Vaeja, Land of the Aryans, in the Zoroastrian book of Vendidad. Sogdiana, at different periods of time, included territories around Samarkand, Bukhara, Khujand and Kesh in modern Uzbekistan. Sogdiana, was captured in 327 B.C.E. by the forces of Alexander the Great, who united Sogdiana with Bactria into one satrapy. It formed part of the Hellenistic Greco-Bactrian kingdom, founded in 248 B.C.E. by Diodotus, for about a century, and was occupied by nomads when the Scythians and Yuezhis overran it around 150 B.C.E.

The Sogdians occupied a key position along the ancient Silk Road, and played a major role in facilitating trade between China and Central Asia. They were the main caravan merchants of Central Asia and dominated the East-West trade from after the fourth century until the eighth century, when they were conquered by the Arabs. Though the Sogdian language is extinct, there remains a large body of literature, mainly religious texts.

History

Sogdiana or Sogdia (Tajik: –°—É“ď–ī - Old Persian: Sughuda; Persian: ō≥ōļōĮ; Chinese: Á≤üÁČĻ - S√Ļt√®) was the ancient civilization of an Iranian people and a province of the Achaemenid Persian Empire, the eighteenth in the list in the Behistun Inscription of Darius the Great (i. 16). Sogdiana is "listed" as the second 'good lands and countries' that Ahura Mazda created. This region is listed after the first, Airyana Vaeja, Land of the Aryans, in the Zoroastrian book of Vendidad, showing its antiquity.[1]Sogdiana, at different periods of time, included territories around Samarkand, Bukhara, Khujand and Kesh in modern Uzbekistan.

Excavations have shown that Sogdiana was probably settled between 1000 and 500 B.C.E.. The Achaemenid empire conquered the area in the sixth century B.C.E.[2].

The Sogdian states, although never politically united, were centered around their main city of Samarkand. It lay north of Bactria, east of Khwarezm, and southeast of Kangju between the Oxus (Amu Darya) and the Jaxartes (Syr Darya), embracing the fertile valley of the Zarafshan (ancient Polytimetus). Sogdian territory corresponds to the modern provinces of Samarkand and Bokhara in modern Uzbekistan as well as the Sughd province of modern Tajikistan.

Hellenistic period

The Sogdian Rock or Rock of Ariamazes, a fortress in Sogdiana, was captured in 327 B.C.E. by the forces of Alexander the Great, who united Sogdiana with Bactria into one satrapy. Subsequently it formed part of the Hellenistic Greco-Bactrian kingdom, founded in 248 B.C.E. by Diodotus, for about a century. Euthydemus I seems to have held the Sogdian territory, and his coins were later copied locally. Eucratides apparently recovered sovereignty over Sogdia temporarily. Finally, the area was occupied by nomads when the Scythians and Yuezhis overran it around 150 B.C.E.

Contacts with China

The Sogdians occupied a key position along the ancient Silk Road, and played a major role in facilitating trade between China and Central Asia. Their contacts with China were triggered by the embassy of the Chinese explorer Zhang Qian during the reign of Wudi of the former Han Dynasty (141-87 B.C.E.). He wrote a report of his visit to Central Asia, and named the area of Sogdiana, "Kangju."

Following Zhang Qian's embassy and report, commercial Chinese relations with Central Asia and Sogdiana flourished, and many Chinese missions were sent throughout the first century B.C.E.: "The largest of these embassies to foreign states numbered several hundred persons, while even the smaller parties included over 100 members… In the course of one year anywhere from five or six to over ten parties would be sent out." (Shiji, trans. Burton Watson). However the Sogdian traders were then still less important in the Silk Road trade than their southern Indian and Bactrian neighbors.

Central Asian Role

.

The Sogdians dominated the East-West trade from after the fourth century until the eighth century, with Suyab and Talas ranking among their main centers in the north. They were the main caravan merchants of Central Asia. Their commercial interests were protected by the resurgent military power of the G√∂kt√ľrks, whose empire has been described as "the joint enterprise of the Ashina clan and the Soghdians" [3] [4]. In the eighth century the Arabs conquered Sogdiana, and it became one of the richest parts of the Caliphate. However, economic prosperity was combined with cultural assimilation. In the second half of the eighth and the ninth centuries, urban citizens adopted Islam, and simultaneously Persian (Tajik) language replaced Sogdian, although for a long time afterwards inhabitants of rural areas continued to speak Sogdian. In the ninth century, Sogdiana lost its ethnic and cultural distinctiveness, although many elements of Sogdian material culture are found in materials dating from the ninth to the eleventh centuries, and its culture survived until the eleventh century among Sogdian immigrants who resettled in eastern Central Asia and China. [5] Sogdian trade, with some interruptions, continued in the ninth century. It continued in the tenth century within the framework of the Uighur Empire, which until 840 extended all over northern Central Asia and obtained from China enormous deliveries of silk in exchange for horses. At that time, caravans of Sogdians traveling to Upper Mongolia are mentioned in Chinese sources.

Sogdians played an equally important religious and cultural role. Part of the data about eastern Asia provided by Muslim geographers of the tenth century is drawn from Sogdian data of the period 750-840, showing the survival of links between east and west. However, after the end of the Uighur Empire, Sogdian trade entered a crisis. What mainly issued from Muslim Central Asia was the trade of the Samanids, which resumed the northwestern road leading to the Khazars and the Urals and the northeastern one toward the nearby Turkic tribes [4].

Language and Culture

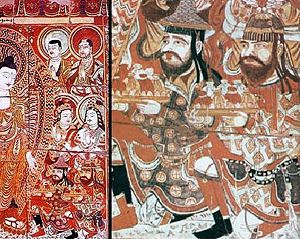

Archaeological findings at Pendzhikent and Varakhsha, town principalities in Sogdiana, are evidence that the Sogdians combined the influences of many cultures, including those of the original Sasanian culture, of post-Gupta India, and of China of the Sui and T'ang periods. Dwellings were decorated with wall paintings and carved wood. The paintings seem to draw heavily on Persian tradition, but the wood carvings are more suggestive of Indian sources. The paintings reproduce many details of everyday life, and their subject matter draws on Iranian (Zoroastrian), Near Eastern (Manichaean, Nestorian), and Indian (Hindu, Buddhist) sources.

The Sogdians were noted for their tolerance of different religious beliefs. Buddhism, Manichaeism, Nestorian Christianity, and Zoroastrianism all had significant followings. Sogdians were actors in the Silk Road transmission of Buddhism, until the period of Muslim invasion in the eighth century. Much of our knowledge of the Sogdians and their language comes from the numerous religious texts that they have left behind.

The valley of the Zarafshan, around Samarkand, retained the name of the Soghd O Samarkand even in the Middle Ages. Arabic geographers assessed it as one of the four fairest districts in the world. The Yaghnobis living in the Sughd province of Tajikistan still speak a dialect of the Soghdian language.

The great majority of the Sogdian people gradually mixed with other local groups such as the Bactrians, Chorasmians, Turks and Persians, and came to speak Persian (modern Tajiks) or (after the Turkic conquest of Central Asia) Turkic Uzbek. They are among the ancestors of the modern Tajik and Uzbek people. Numerous Sogdian words can be found in modern Persian and Uzbek as a result of this admixture.

Sogdian Language

The Sogdians spoke an Eastern Iranian language called Sogdian, closely related to Bactrian, another major language of the region in ancient times. Sogdian was written in a variety of scripts, all of them derived from the Aramaic alphabet. Like its close relative the Pahlavi writing system, written Sogdian also contains many logograms or ideograms, which were Aramaic words written to represent native spoken ones. Various Sogdian pieces, almost entirely religious works of Manichaean and Christian writers, have also been found in the Turfan text corpus. Sogdian script is the direct ancestor of Uyghur script, itself the forerunner of the Mongolian script.

- Sample Sogdian text (transliteration): MN ső≥wőīy-k MLK‚Äô őīy-w‚ÄôŇ°ty-c ‚Äôt x‚Äôxsrc xwő≤w ‚ÄôpŇ°wnw őīrwth ő≥-rő≤ nm‚Äôcyw

- Word-by-word translation: From Sogdiana's King Dewashtic to Khakhsar's Khuv Afshun, (good) health (and) many salutations…

Sogdian is one of the most important Middle Iranian languages with a large literary corpus, standing next to Middle Persian and Parthian. The language belongs to the Northeastern branch of Iranian languages. No evidence of an earlier version of the language (*Old Sogdian) has been found. Sogdian possesses a more conservative grammar and morphology than Middle Persian.

The economic and political importance of the language guaranteed its survival in the first few centuries after the conquest of Sogdiana by the Muslims in the early eighth century C.E.. The earliest texts of Modern Persian were written in the territory of Sogdiana under the patronage of Samanid Kings, and many Sogdian words have entered Modern Persian. Only a dialect of Sogdian, called Yaghnobi language, has survived into the twenty-first century and is spoken by the mountain dwellers of the Yaghnob valley.

Famous Sogdians

- An Lushan was a military leader of Turkic and Sogdian origin during the Tang Dynasty in China. He rose to prominence by fighting during the Tang Frontier Wars between 741 and 755. Later, he precipitated the catastrophic An Shi Rebellion, which lasted from 755 to 763.

See also

- Shakya

- Tocharians

- Iranian languages

- Ancient Iranian peoples

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ James Darmesteter, (translator) (From Sacred Books of the East, American Edition, 1898.) [1] Avesta.org. Retrieved March 31, 2008.

- ‚ÜĎ Boris I. Marshak. The Archeology of Sogdiana, The Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg. The Silk Road Foundation Newsletter.

- ‚ÜĎ Andr√© Wink. Al-Hind: The Making of the Indo-Islamic World. (Brill Academic Publishers, 2002. ISBN 0391041738).

- ‚ÜĎ 4.0 4.1 √ątienne de la Vaissi√®re, "Sogdian Trade," Encyclopedia Iranica, Iranica.com. retrieved 15 June 2007.

- ‚ÜĎ Marshak. The Archeology of Sogdiana Retrieved December 18, 2007

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

- Babadjan Ghafurov, "Tajiks," published in USSR, Russia, Tajikistan

- MacLeod, Calum, and Bradley Mayhew. 2002. Uzbekistan the golden road to Samarkand. Hong Kong: Odyssey. ISBN 9622177034 ISBN 9789622177031

- Frye, Richard Nelson. 1996. The heritage of Central Asia from antiquity to the Turkish expansion. Princeton series on the Middle East. Princeton: Markus Wiener Publishers. ISBN 1558761101

- Marshak, B. I., and V. A. LivshitÔł†sÔł°. 2002. Legends, tales, and fables in the art of Sogdiana. Biennial Ehsan Yarshater lecture series, no. 1. New York: Bibliotheca Persica Press. ISBN 0933273614

- Vaissi√®re, √ątienne de la, "Histoire des marchands sogdiens" [Biblioth√®que de l'Institut des Hautes √ątudes Chinoises, XXXII]. Indo-Iranian Journal 47 (2) (June 2004): 133-135

- Vaissière, Etienne, de la. Histoire des marchands sogdiens. Ihec/Inst.Hautes Etudes (1 janvier 2004) Paris: de Boccard, 2004. ISBN 2857570643 (in French)

- Vaissière, Etienne de la. Sogdian Traders. A History. 2005. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 9004142525

- Wink, André. Al-Hind: The Making of the Indo-Islamic World. Brill Academic Publishers, 2002. ISBN 0391041738.

| ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.