Red Sea

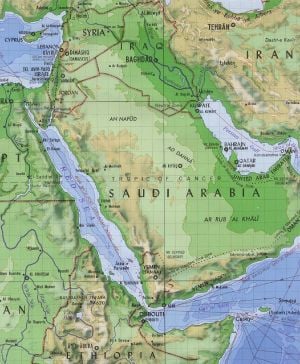

The Red Sea, one of the most saline bodies of water in the world, is an inlet of the Indian Ocean between Africa and Asia. The connection to the ocean is in the south through the Bab el Mandeb sound and the Gulf of Aden. In the north are the Sinai Peninsula, the Gulf of Aqaba, and the Gulf of Suez (leading to the Suez Canal). The Sea has played a crucial navigational role since ancient times.

Occupying a part of the Great Rift Valley, the Red Sea has a surface area of about 174,000 square miles (450,000 km²): Being roughly 1,200 miles (1,900 km) long and, at its widest point, over 190 miles (300 km) wide. It has a maximum depth of 8,200 feet (2,500 m) in the central median trench and an average depth of 1,640 feet (500 m), but there are also extensive shallow shelves, noted for their marine life and corals. This, the world's most northern tropical sea, is the habitat of over 1,000 invertebrate species and 200 soft and hard corals.

The world's largest independent conservation organization, the World Wide Fund for Nature, has identified the Red Sea as a "Global 200" ecoregion. As such, it is considered a priority for conservation.

Name

Red Sea is a direct translation of the Greek Erythra Thalassa (Ερυθρά Θάλασσα), Latin Mare Rubrum, Arabic Al-Baḥr Al-Aḥmar (البحر الأحمر), and Tigrinya Qeyḥ bāḥrī (ቀይሕ ባሕሪ).

The name of the sea may signify the seasonal blooms of the red-colored cyanobacteria Trichodesmium erythraeum near the water's surface. Some suggest that it refers to the mineral-rich red mountains nearby which are called Harei Edom (הרי אדום). Edom, meaning "ruddy complexion," is also an alternative Hebrew name for the red-faced biblical character Esau (brother of Jacob), and the nation descended from him, the Edomites, which in turn provides yet another possible origin for Red Sea.

Another hypothesis is that the name comes from the Himyarite, a local group whose own name means red.

Yet another theory favored by some modern scholars is that the name red is referring to the direction south, the same way the Black Sea's name may refer to north. The basis of this theory is that some Asiatic languages used color words to refer to the cardinal directions. Herodotus on one occasion uses "Red Sea" and "Southern Sea" interchangeably.

A final theory suggests that it was named so because it borders the Egyptian Desert which the ancient Egyptians called the Dashret or "red land"; therefore, it would have been the sea of the red land.

The association of the Red Sea with the Biblical account of the Exodus, in particular in the Passage of the Red Sea, goes back to the Septuagint translation of the book of Exodus from Hebrew into Koine, in which Hebrew Yam suph (ים סוף), meaning Reed Sea, is translated as Erythra Thalassa (Red Sea). Yam Suph is also the name for the Red Sea in modern Hebrew.

History

The earliest known exploration expeditions of the Red Sea were conducted by Ancient Egyptians seeking to establish commercial routes to Punt. One such expedition took place around 2500 B.C.E. and another around 1500 B.C.E. Both involved long voyages down the Red Sea.[1]

The Biblical book of Exodus tells the story of the Israelites' miraculous crossing of a body of water, which the Hebrew text calls Yam Suph, traditionally identified as the Red Sea. The account is part of the Israelites' escape from slavery in Egypt, and is told in Exodus 13:17—15:21.

In the sixth century B.C.E., Darius I of Persia sent reconnaissance missions to the Red Sea, improving and extending navigation by locating many hazardous rocks and currents. A canal was built between the Nile and the northern end of the Red Sea at Suez. In the late fourth century B.C.E., Alexander the Great sent Greek naval expeditions down the Red Sea to the Indian Ocean. Greek navigators continued to explore and compile data on the Red Sea.

Agatharchides collected information about the sea in the second century B.C.E. The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, written sometime around the first century C.E., contain a detailed description of the Red Sea's ports and sea routes.[1] The Periplus also describes how Hippalus first discovered the direct route from the Red Sea to India.

The Red Sea was favored for Roman trade with India beginning with the reign of Augustus, when the Roman Empire gained control over the Mediterranean, Egypt, and the northern Red Sea. The route had been used by previous states but grew in the volume of traffic under the Romans. From Indian ports, goods from China were introduced to the Roman world. Contact between Rome and China depended on the Red Sea, but the route was broken by the Aksumite Empire around the third century C.E.[2]

During medieval times the Red Sea was an important part of the Spice trade route.

In 1798, France charged Napoleon Bonaparte with invading Egypt and capturing the Red Sea. Although he failed in his mission, the engineer J.B. Lepere, who took part in it, revitalized the plan for a canal which had been envisaged during the reign of the Pharaohs. Several canals were built in ancient times, but none lasted long.

The Suez Canal was opened in November 1869. At the time, the British, French, and Italians shared the trading posts. The posts were gradually dismantled following the First World War. After the Second World War, the Americans and Soviets exerted their influence while the volume of oil tanker traffic intensified. However, the Six Day War culminated in the closure of the Suez Canal from 1967 to 1975. Today, in spite of patrols by the major maritime fleets in the waters of the Red Sea, the Suez Canal has never recovered its supremacy over the Cape route, which is believed to be less vulnerable.

Oceanography

The Red Sea lies between arid land, desert, and semi-desert. The main reasons for the better development of reef systems along the Red Sea is because of its greater depths and an efficient water circulation pattern. The Red Sea water mass exchanges its water with the Arabian Sea and Indian Ocean via the Gulf of Aden. These physical factors reduce the effect of high salinity caused by evaporation and cold water in the north and relatively hot water in the south.

Climate: The climate of the Red Sea is the result of two distinct monsoon seasons; a northeasterly monsoon and a southwesterly monsoon. Monsoon winds occur because of the differential heating between the land surface and sea. Very high surface temperatures coupled with high salinities makes this one of the hottest and saltiest bodies of seawater in the world. The average surface water temperature of the Red Sea during the summer is about 26 °C (79 °F) in the north and 30 °C (86 °F) in the south, with only about 2 °C (3.6 °F) variation during the winter months. The overall average water temperature is 22 °C (72 °F). The rainfall over the Red Sea and its coasts is extremely low, averaging 0.06 m (2.36 in) per year; the rain is mostly in the form of showers of short spells often associated with thunderstorms and occasionally with dust storms. The scarcity of rainfall and no major source of fresh water to the Red Sea result in the excess evaporation as high as 205 cm (81 in) per year and high salinity with minimal seasonal variation.

Salinity: The Red Sea is one of the most saline water bodies in the world, due to the effects of the water circulation pattern, resulting from evaporation and wind stress. Salinity ranges between 3.6 and 3.8 percent.

Tidal range: In general, tide ranges between 0.6 m (2.0 ft) in the north, near the mouth of the Gulf of Suez and 0.9 m (3.0 ft) in the south near the Gulf of Aden but it fluctuates between 0.20 m (0.66 ft) and 0.30 m (0.98 ft) away from the nodal point. The central Red Sea (Jeddah area) is therefore almost tideless, and as such the annual water level changes are more significant. Because of the small tidal range the water during high tide inundates the coastal sabkhas as a thin sheet of water up to a few hundred meters rather than inundating the sabkhas through a network of channels. However, south of Jeddah in the Shoiaba area, the water from the lagoon may cover the adjoining sabkhas as far as 3 km (2 mi) whereas, north of Jeddah in the Al-kharrar area the sabkhas are covered by a thin sheet of water as far as 2 km (1.2 mi). The prevailing north and northeastern winds influence the movement of water in the coastal inlets to the adjacent sabkhas, especially during storms. Winter mean sea level is 0.5 m (1.6 ft) higher than in summer. Tidal velocities passing through constrictions caused by reefs, sand bars and low islands commonly exceed 1-2 meters per second (3–6.5 ft/s).

Current: In the Red Sea, detailed current data is lacking, partially because they are weak and variable both spatially and temporally. Temporal and spatial currents variation is as low as 0.5 m (1.6 ft) and are governed mostly by wind. In summer, NW winds drive surface water south for about four months at a velocity of 15-20 cm per second (6–8 in/sec), whereas in winter the flow is reversed, resulting in the inflow of water from the Gulf of Aden into the Red Sea. The net value of the latter predominates, resulting in an overall drift to the northern end of the Red Sea. Generally, the velocity of the tidal current is between 50-60 cm per second (20–23.6 in/sec) with a maximum of 1 m (3 ft) per sec. at the mouth of the al-Kharrar Lagoon. However, the range of north-northeast current along the Saudi coast is 8-29 cm per second (3–11.4 in/sec).

Wind Regime: With the exception of the northern part of the Red Sea, which is dominated by persistent north-west winds, with speeds ranging between 7 km/h (4 mph) and 12 km/h (7 mph), the rest of the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden are subjected to the influence of regular and seasonally reversible winds. The wind regime is characterized by both seasonal and regional variations in speed and direction with average speed generally increasing northward.

Wind is the driving force in the Red Sea for transporting the material either as suspension or as bedload. Wind induced currents play an important role in the Red Sea in initiating the process of resuspension of bottom sediments and transfer of materials from sites of dumping to sites of burial in quiescent environment of deposition. Wind generated current measurement is therefore important in order to determine the sediment dispersal pattern and its role in the erosion and accretion of the coastal rock exposure and the submerged coral beds.

Geology

The Red Sea formed when Arabia split from Africa due to plate tectonics. This split started in the Eocene and accelerated during the Oligocene. The sea is still widening and it is considered that the sea will become an ocean in time (as proposed in the model of John Tuzo Wilson).

Sometime during the Tertiary period, the Bab el Mandeb closed and the Red Sea evaporated to an empty hot dry salt-floored sink. Effects causing this would be:

- A "race" between the Red Sea widening and Perim Island erupting filling the Bab el Mandeb with lava.

- The lowering of world sea level during the Ice Ages due to much water being locked up in the ice caps.

Today, surface water temperatures remain relatively constant at 21–25 °C (70–77 °F) and temperature and visibility remain good to around 660 feet (200 m), but the sea is known for its strong winds and tricky local currents.

In terms of salinity, the Red Sea is greater than the world average, approximately 4 percent. This is due to several factors: 1) high rate of evaporation and very little precipitation, 2) a lack of significant rivers or streams draining into the sea, and 3) limited connection with the Indian Ocean (and its lower water salinity).

A number of volcanic islands rise from the center of the sea. Most are dormant, but in 2007, Jabal al-Tair island erupted violently.

Living resources

The Red Sea is a rich and diverse ecosystem. More than 1,100 species of fish[3] have been recorded in the Red Sea, with approximately 10 percent of these being endemic to the Red Sea.[4] This also includes around 75 species of deepwater fish.[3]

The rich diversity is in part due to the 2,000 km (1,240 mi) of coral reef extending along its coastline; these fringing reefs are 5000-7000 years old and are largely formed of stony acropora and porites corals. The reefs form platforms and sometimes lagoons along the coast and occasional other features such as cylinders (such as the blue hole at Dahab). These coastal reefs are also visited by pelagic species of red sea fish, including some of the 44 species of shark.

The special biodiversity of the area is recognized by the Egyptian government, who set up the Ras Mohammed National Park in 1983. The rules and regulations governing this area protect local wildlife, which has become a major attraction for tourists, in particular for diving enthusiasts. Divers and snorkelers should be aware that although most Red Sea species are innocuous, a few are hazardous to humans.[5]

Other marine habitats include sea grass beds, salt pans, mangroves, and salt marshes.

Mineral resources

In terms of mineral resources the major constituents of the Red Sea sediments are as follows:

- Biogenic constituents:

- Nannofossils, foraminifera, pteropods, siliceous fossils

- Volcanogenic constituents:

- Tuffites, volcanic ash, montmorillonite, cristobalite, zeolites

- Terrigenous constituents:

- Authigenic minerals:

- Sulfide minerals, aragonite, Mg-calcite, protodolomite, dolomite, quartz, chalcedony

- Evaporite minerals:

- Brine precipitate:

- Fe-montmorillonite, goethite, hematite, siderite, rhodochrosite, pyrite, sphalerite, anhydrite

Desalination plants

There is extensive demand of desalinated water to meet the requirement of the population and the industries along the Red Sea.

There are at least 18 desalination plants along the Red Sea coast of Saudi Arabia which discharge warm brine and treatment chemicals (chlorine and anti-scalants) that may cause bleaching and mortality of corals and diseases to the fish stocks. Although this is only a localized phenomenon, it may intensify with time and have a profound impact on the fishing industry.

The water from the Red Sea is also utilized by oil refineries and cement factories for cooling purposes. Used water drained back into the coastal zones may cause harm to the nearshore environment of the Red Sea.

Facts and figures at a glance

- Length: ~1,900 km (1,181 mi)—79 percent of the eastern Red Sea with numerous coastal inlets

- Maximum Width: ~306–354 km (190–220 mi)—Massawa (Eritrea)

- Minimum Width: ~26–29 km (16–18 mi)—Bab el Mandeb Strait (Yemen)

- Average Width: ~280 km (174 mi)

- Average Depth: ~490 m (1,608 ft)

- Maximum Depth: ~2,850 m (9,350 ft)

- Surface Area: 438-450 x 10² km² (16,900–17,400 sq mi)

- Volume: 215–251 x 10³ km³ (51,600–60,200 cu mi)

- Approximately 40 percent of the Red Sea is quite shallow (under 100 m/330 ft), and about 25 percent is under 50 m (164 ft) deep.

- About 15 percent of the Red Sea is over 1,000 m (3,300 ft) depth that forms the deep axial trough.

- Shelf breaks are marked by coral reefs

- Continental slope has an irregular profile (series of steps down to ~500 m/1,640 ft)

- Center of Red Sea has a narrow trough (~1,000 m/3,281 ft; some depths may exceed 2,500 m/8,202 ft)

Some of the research cruises in the Red Sea

Numerous research cruises have been conducted:

- Arabia Felix (1761-1767)

- Vitiaz (1886-1889)

- Valdivia (1898-1894)

- Pola (1897-98) Southern Red Sea and (1895/96—Northern Red Sea

- Ammiraglio Magnaghi (1923/24)

- Snellius (1929–1930)

- Mabahiss (1933-1934 and 1934-1935)

- Albatross (1948)

- Manihine (1849 and 1952)

- Calypso (1955)

- Atlantis and Vema (1958)

- Xarifa (1961)

- Meteor (1961)

- Glomar Challenger (1971)

- Sonne (1997)

- Meteor (1999)

Tourism

The sea is known for its spectacular dive sites such as Ras Mohammed, SS ''Thistlegorm'' (shipwreck), Elphinstone, The Brothers and Rocky Island in Egypt, Dolphin Reef in Eilat, Israel and less known sites in Sudan such as Sanganeb, Abington, Angarosh and Shaab Rumi.

The Red Sea became known a sought-after diving destination after the expeditions of Hans Hass in the 1950s, and later by Jacques-Yves Cousteau. Popular tourist resorts include Sharm-El-Sheikh and Hurghada (and recently Marsa Alam) and Dahab in Egypt, as well as Eilat, Israel, in an area known as the Red Sea Riviera.

Bordering countries

Countries bordering the Red Sea include:

|

Towns and cities

Towns and cities on the Red Sea coast include:

|

|

|

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Felipe Fernandez-Armesto, Pathfinders: A Global History of Exploration (W.W. Norton & Company, 2006, ISBN 0393062597).

- ↑ W. Gordon East, The Geography behind History (W.W. Norton & Company, 1965, ISBN 0393004198).

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 R. Froese and D. Pauly, FishBase. Retrieved June 4, 2008.

- ↑ A. Siliotti, Fishes of the Red Sea (Verona: Geodia, 2003, ISBN 8887177422).

- ↑ E. Lieske and R.F. Myers, Coral Reef Guide; Red Sea (London: HarperCollins, 2004, ISBN 0007159862).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- The Catholic Encyclopedia. Red Sea Retrieved June 4, 2008.

- Cousteau, Jacques Yves. 1971. Life and Death in a Coral Sea. The Undersea Discoveries of Jacques-Yves Cousteau. Garden City, NY: Doubleday.

- Farid, Abdel Majid. 1984. The Red Sea: Prospects for Stability. London: Croom Helm in association with the Arab Research Centre. ISBN 978-0709905431.

- Hamblin, W. Kenneth, and Eric H. Christiansen. Earth's Dynamic Systems, 8th edition. Upper Saddle River: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1998. ISBN 0137453736.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.