| Six-Day War (Arab-Israeli conflict) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

IDF soldiers at Jerusalem's Western Wall shortly after its capture. | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Combatants | |||||||||||

| Active: Aided by: | |||||||||||

| Commanders | |||||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||||

| 264,000 (incl. 50,000 regular troops); 197 combat aircraft | Egypt 150,000; Syria 75,000; Jordan 55,000; Saudi Arabia 20,000; 812 combat aircraft | ||||||||||

| Casualties | |||||||||||

| 779 killed, 2,563 wounded, 15 prisoners (official casualties) |

21,000 killed, 45,000 wounded, 6,000 prisoners over 400 aircraft destroyed (estimates) | ||||||||||

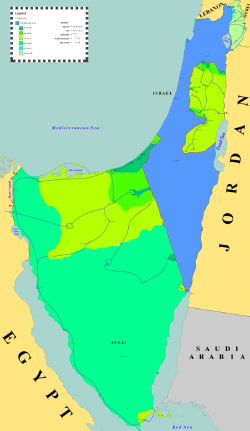

The Six-Day War (Arabic: حرب الأيام الستة, ħarb al‑ayyam as‑sitta ; Hebrew: מלחמת ששת הימים, Milhemet Sheshet Ha‑Yamim), also known as the 1967 Arab-Israeli War, the Third Arab-Israeli War, Six Days' War, an‑Naksah (The Setback), or the June War, was fought between Israel and the Arab states of Egypt, Jordan, Iraq, and Syria. When Egypt expelled the United Nations Emergency Force from the Sinai Peninsula, increased its military activity near the border, and blockaded the Straits of Tiran to Israeli ships, Israel launched a preemptive attack on Egypt's air force, fearing an imminent invasion by Egypt. At the war's end, Israel had gained control of the Gaza Strip, the Sinai Peninsula, the West Bank, and the Golan Heights. The results of the war affect the geopolitics of the region to this day.

On November 22, 1967, UN Security Council passed Resolution 242 calling for Israel's withdrawal to the pre-1967 borders.[1] Since then, many use this resolution to describe Israel as occupiers, stating "three million Palestinians live in the area that became Israeli occupied territory, subject to military law. Israeli settlements have been built in the Occupied Territories. The Golan Heights and Jerusalem have been annexed." On the other hand, others see the situation differently. Worldwide support for Israel from the Jewish community increased after 1967, as its survival seemed much more likely. The Sinai was returned to Egypt following the Camp David Accords of 1979, while the rest of the occupied territory (apart from the Golan) became the Palestinian National Authority in 1993. However, lack of progress towards implementing the two-state solution proposed by the Camp David Process, subsequently endorsed both by the Oslo Accords and by the 2003 Road map for Peace[2] have seen the eruption of two intifadas and continued violence against Israel followed by Israeli reprisals.

Background

Suez Crisis aftermath

The Suez Crisis represented for Egypt a military defeat, but a political victory. Heavy diplomatic pressure from both the United States and the Soviet Union forced Israel to withdraw its military from the Sinai Peninsula. After the 1956 war, Egypt agreed to the stationing of a UN peacekeeping force in the Sinai, the United Nations Emergency Force, to keep that border region demilitarized, and prevent guerrillas from crossing the border into Israel. As a result the border between Egypt and Israel quieted for a while.

The aftermath of the 1956 war saw the region return to an uneasy balance without any lasting resolution of the region's difficulties. At the time, no Arab state had recognized Israel. Syria, aligned with the Soviet bloc, began sponsoring guerrilla raids on Israel in the early 1960s as part of its "people's war of liberation," designed to deflect domestic opposition to the Ba'ath Party.[3]

Israel's National Water Carrier

In 1964, Israel began withdrawing water from the Jordan River for its National Water Carrier. The following year, the Arab states began construction of the Headwater Diversion Plan, which, once completed, would divert the waters of the Banias Stream so that the water would not enter Israel, and the Sea of Galilee, but rather flow into a dam at Mukhaiba for Jordan and Syria, and divert the waters of the Hasbani into the Litani, in Lebanon. The diversion works would have reduced the installed capacity of Israel's carrier by about 35 percent. The Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) attacked the diversion works in Syria in March, May, and August of 1965, perpetuating a prolonged chain of border violence that lead directly to the events precipitating the war.[4]

Israel and Jordan: The Samu Incident

On November, 12, 1966, an Israeli border patrol hit a mine, killing three soldiers and injuring six others. The Israelis believed the mine had been planted by terrorists from Es Samu on the West Bank. Early on the morning November 13, King Hussein, who had been having secret meetings with Abba Eban and Golda Meir for three years concerning peace and secure borders, received an unsolicited message from his Israeli contacts stating that Israel had no intention of attacking Jordan.[5] However, at 5:30 am, in what Hussein described as an action carried out "under the pretext of 'reprisals against the terrorist activities of the P.L.O.,' Israeli forces attacked Es Samu, a village in Jordanian-occupied West Bank of 4,000 inhabitants, all of them Palestinian refugees whom the Israelis accused of harboring terrorists from Syria".[6]

In "Operation Shredder," Israel's largest military operation since 1956, a force of around 3,000-4,000 soldiers backed by tanks and aircraft divided into a reserve force, which remained on the Israeli side of the border, and two raiding parties, which crossed into the Jordanian-occupied West Bank. The 48th Infantry Battalion of the Jordanian army, commanded by Major Asad Ghanma, ran into the Israeli forces north-west of Samu and two companies approaching from the north-east were intercepted by the Israelis, while a platoon of Jordanians armed with two 106 mm recoilless guns entered Samu. In the ensuing battles three Jordanian civilians and fifteen soldiers were killed; fifty-four other soldiers and ninety-six civilians were wounded. The commander of the Israeli paratroop battalion, Colonel Yoav Shaham, was killed and ten other Israeli soldiers were wounded.[7] According to the Israeli Government, fifty Jordanians were killed but the true number was never disclosed by the Jordanians in an effort to keep up morale and confidence in King Hussein's regime.[8]

Facing a storm of criticism from Jordanians, Palestinians, and his Arab neighbors for failing to protect Samu, Hussein ordered a nation-wide mobilization on November 20.[9]

On November 25, the United Nations Security Council adopted Resolution 228 unanimously deploring "the loss of life and heavy damage to property resulting from the action of the Government of Israel on 13 November 1966," censuring "Israel for this large-scale military action in violation of the United Nations Charter and of the General Armistice Agreement between Israel and Jordan" and emphasizing "to Israel that actions of military reprisal cannot be tolerated and that, if they are repeated, the Security Council will have to consider further and more effective steps as envisaged in the Charter to ensure against the repetition of such acts."[10]

In a telegram to the State Department on May 18, 1967, the U.S. ambassador in Amman, Findley Burns, reported that King Hussein had expressed the opinion in a conversation the day before that "Jordan is just as likely a target in the short run and, in his opinion, an inevitable one in the long run… Israel has certain long range military and economic requirements and certain traditional religious and historic aspirations which in his opinion they have not yet satisfied or realized. The only way in which these goals can be achieved, he said, is by an alteration of the status of the Occupied West Bank (never internationally recognized as Jordanian). Thus in the King's view it is quite natural for the Israelis to take advantage of any opportunity and force any situation which would move them closer to this goal. His concern is that current area conditions provide them with just such opportunities-terrorism, infiltration and disunity among the Arabs being the most obvious," and recalling the Samu incident "Hussein said that if Israel launched another Samu-scale attack against Jordan he would have no alternative but to retaliate or face an internal revolt. If Jordan retaliates, asked Hussein, would not this give Israel a pretext to occupy and hold Jordanian or Occupied territory? Or, said Hussein, Israel might instead of a hit-and-run type attack simply occupy and hold territory in the first instance. He said he could not exclude these possibilities from his calculations and urged us not to do so even if we felt them considerably less than likely."[11]

Israel and Syria

In addition to sponsoring attacks against Israel (often through Jordanian territory), Syria also began shelling Israeli civilian communities in north-eastern Galilee, from positions on the Golan Heights, as part of the dispute over control of the Demilitarized Zones (DMZs), small parcels of land claimed by both Israel and Syria.[12]

In 1966, Egypt and Syria signed a military alliance, initiated for both sides if either were to go to war. According to Egyptian Foreign Minister Mahmoud Riad, Egypt had been persuaded to enter into the mutual defense pact by the Soviet Union. From the Soviet perspective the pact had two objectives:

- To reduce the chances of a punitive attack on Syria by Israel

- To bring the Syrians under what they considered to be Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser's moderate influence.[13]

During a visit to London in February 1967, Israeli Foreign Minister Abba Eban briefed journalists on Israel's "hopes and anxieties," explaining to those present that although the governments of Lebanon, Jordan, and the United Arab Republic seemed to have decided against active confrontation with Israel it remained to be seen whether Syria could maintain a minimal level of restraint, at which hostility was confined to rhetoric.

On April 7, 1967, a minor border incident escalated into a full-scale aerial battle over the Golan Heights, resulting in the loss of six Syrian MiG-21s to Israeli Air Force (IAF) Dassault Mirage IIIs, and the latter's flight over Damascus.[14] Tanks, heavy mortars, and artillery were used in various sections along the 47 mile (76 km) border in what was described as "a dispute over cultivation rights in the demilitarized zone south-east of Lake Tiberias." Earlier in the week, Syria had twice attacked an Israeli tractor working in the area and when it returned on the morning of April 7, the Syrians opened fire again. The Israelis responded by sending in armor-plated tractors to continue plowing, resulting in further exchanges of fire. Israeli aircraft dive-bombed Syrian positions with 250 and 500 kg bombs. The Syrians responded by shelling Israeli border settlements heavily and Israeli jets retaliated by bombing the village of Sqoufiye, destroying around 40 houses. At 3:19pm Syrian shells started falling on Kibbutz Gadot; over 300 landed within the kibbutz compound in only 40 minutes.[15]. The United Nations Truce Supervision Organization attempted to arrange a ceasefire, but Syria declined to cooperate unless Israeli agricultural work was halted.[16]

The Prime Minister of Israel, Levi Eshkol warned that Israel would not hesitate to use air power on the scale of April 7, in response to continued border terrorism and on the same day Israeli envoy Gideon Rafael presented a letter to the president of the Security Council warning that Israel would "act in self-defense as circumstances warrant".[17] In early May the Israeli cabinet authorized a limited strike against Syria, but Rabin's renewed demand for a large-scale strike to discredit or topple the Ba'ath regime was opposed by Eshkol.[18] Border incidents multiplied and numerous Arab leaders, both political and military, called for an end to Israeli reprisals. Egypt, then already trying to seize a central position in the Arab world under Nasser, accompanied these declarations with plans to re-militarize the Sinai. Syria shared these views, although it did not prepare for an immediate invasion. The Soviet Union actively backed the military needs of the Arab states. It was later revealed that on May 13, a Soviet intelligence report given by Soviet President Nikolai Podgorny to Egyptian Vice President Anwar Sadat claimed falsely that Israeli troops were massing along the Syrian border.[19]

Withdrawal of the United Nations Emergency Force

At 10:00pm on May 16, the commander of the United Nations Emergency Force, General Indar Jit Rikhye, was handed a letter from General Mohammed Fawzy, Chief of Staff of the United Arab Republic, reading: "To your information, I gave my instructions to all U.A.R. armed forces to be ready for action against Israel, the moment it might carry out any aggressive action against any Arab country. Due to these instructions our troops are already concentrated in Sinai on our eastern border. For the sake of complete security of all U.N. troops which install Observation posts along our borders, I request that you issue your orders to withdraw all these troops immediately." Rikhye said he would report to the Secretary-General for instructions.[20]

The UN Secretary-General U Thant attempted to negotiate with the Egyptian government, but on May 18, the Egyptian Foreign Minister informed nations with troops in UNEF that the UNEF mission in Egypt and the Gaza Strip had been terminated and that they must leave immediately, and Egyptian forces prevented UNEF troops from entering their posts. The Governments of India and Yugoslavia decided to withdraw their troops from UNEF, regardless of the decision of U Thant. While this was taking place, U Thant suggested that UNEF be redeployed to the Israeli side of the border, but Israel refused, arguing that UNEF contingents from countries hostile to Israel would be more likely to impede an Israeli response to Egyptian aggression than to stop that aggression in the first place.[21] The Permanent Representative of Egypt then informed U Thant that the Egyptian government had decided to terminate UNEF's presence in the Sinai and the Gaza Strip, and requested steps that the force withdraw as soon as possible. On May 19, the UNEF commander was given the order to withdraw.[22] Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser then began the re-militarization of the Sinai, and concentrated tanks and troops on the border with Israel.

The Straits of Tiran

On May 22, Egypt announced that the Straits of Tiran would be closed to "all ships flying Israel flags or carrying strategic materials," with effect from May 23.[23] Also, Nasser stated, "Under no circumstances can we permit the Israeli flag to pass through the Gulf of Aqaba." While most of Israel's commerce used Mediterranean ports, and, according to John Quigley, no Israeli-flag vessel had used the port of Eilat for the two years preceding June 1967, oil carried on non-Israeli flag vessels to Eilat was a very significant import.[24] There were ambiguities, however, about how rigorous the blockade would be, particularly whether it would apply to non-Israeli flag vessels. Citing international law, Israel considered the closure of the straits to be illegal, and it had stated in 1957 when it withdrew from the Sinai and Gaza that it would consider such a blockade a casus belli. The Arab states disputed Israel's right of passage through the Straits, noting that they had not signed the Convention on the Territorial Sea and Contiguous Zone, specifically article 16(4), which provided Israel with that right.[25] In the UN General Assembly debates immediately after the war, many nations argued that even if international law gave Israel the right of passage, Israel was not entitled to attack Egypt to assert it because the closure was not an "armed attack" as defined by article 51 of the UN Charter. Similarly, international law professor John Quigley argues that under the doctrine of proportionality, Israel would only be entitled to use such force as would be necessary to secure its right of passage.[26]

Israel viewed the closure of the straits with some alarm and the U.S. and UK were asked to open the Straits of Tiran, as they guaranteed they would in 1957. Harold Wilson's proposal of an international maritime force to quell the crisis was adopted by President Johnson, but received little support, with only Britain and the Netherlands offering to contribute ships.

Egypt and Jordan

Nasser's pan-Arabism had numerous supporters in Jordan (in spite of Hussein, who felt it threatened his authority); and, on May 30, Jordan signed a mutual defense treaty with Egypt, thereby joining the military alliance already in place between Egypt and Syria. President Nasser, who had called King Hussein an "imperialist lackey" just days earlier, declared: "Our basic objective will be the destruction of Israel. The Arab people want to fight."[27]

At the end of May 1967, Jordanian forces were given to the command of an Egyptian General Abdul Munim Riad.[28] On the same day, Nasser proclaimed: "The armies of Egypt, Jordan, Syria, and Lebanon are poised on the borders of Israel … to face the challenge, while standing behind us are the armies of Iraq, Algeria, Kuwait, Sudan, and the whole Arab nation. This act will astound the world. Today they will know that the Arabs are arranged for battle, the critical hour has arrived. We have reached the stage of serious action and not of more declarations."[29] Israel called upon Jordan numerous times to refrain from hostilities. Hussein, however, was caught on the horns of a galling dilemma: allow Jordan to be dragged into war and face the brunt of the Israeli response, or remain neutral and risk full-scale insurrection among his own people. Army Commander-in-Chief General Sharif Zaid Ben Shaker warned in a press conference that "If Jordan does not join the war a civil war will erupt in Jordan."[30]

Israel's own sense of concern regarding Jordan's future role originated in Jordanian control of the West Bank. This put Arab forces just 17 kilometres from Israel's coast, a jump-off point from which a well coordinated tank assault would likely cut Israel in two within half an hour. Such a coordinated attack from the West Bank was always viewed by the Israeli leadership as a threat to Israel's existence. Although the size of Jordan's army meant that Jordan was probably incapable of executing such a maneuver, the country was perceived as having a history of being used by other Arab states as staging grounds for operations against Israel; thus, attack from the West Bank was always viewed by the Israeli leadership as a threat to Israel's existence. At the same time several other Arab states not bordering Israel, including Iraq, Sudan, Kuwait, and Algeria, began mobilizing their armed forces.

The drift to war

On May 21, Nasser told General ‘Ali ‘Amer, Defense Minister Shams al-Din Badran and Vice President Zakkariya Muhieddin that closing the Straits of Tiran would raise the chance of war to 50 percent, then indeed actually ordered blockade. The blockade was a violation the 1958 Geneva Convention, which admittedly Egypt did not sign, guaranteeing the international status of straits. However, the USSR, who had been sponsoring Egypt and the Arab states, had signed the treaty. Nasser said that "We knew that closing the Gulf of Aqaba meant war…the objective will be Israel’s destruction," which to him was along the same lines as striking Soviet-hostile America. "Israel today is the United States," Nasser said.

In his speech to Arab trade unionists on May 26, Nasser announced: "If Israel embarks on an aggression against Syria or Egypt, the battle will be a general one… and our basic objective will be to destroy Israel."[31]

Israeli Foreign Minister Abba Eban wrote in his autobiography that when he was told by U Thant of Nasser's promise not to attack Israel he found this reassurance convincing as "…Nasser did not want war; he wanted victory without war".[32] Israel's political and military elite felt that preemption was not merely militarily preferable, but inevitably transformative.

Diplomacy and intelligence assessments

The Israeli cabinet met on May 23, and decided to launch a preemptive strike if the Straits of Tiran were not re-opened by May 25. Following an approach from U.S. Undersecretary of State Eugene Rostow to allow time for the negotiation of a nonviolent solution, Israel agreed to a delay of ten days to two weeks.[33] UN Secretary General, U Thant, visited Cairo for mediation and recommended moratorium in the Straits of Tiran and a renewed diplomatic effort to solve the crisis. Egypt agreed and Israel rejected these proposals. It should be noted that Nasser's concessions do not necessarily suggest that he was making a concerted effort to avoid war any more than Israel's rejection implies that Israel wanted a war. The decision benefited him both politically and strategically. Agreeing to diplomacy helped garner international political support. Moreover every delay gave Egypt time to complete its own military preparations and coordinate with the other Arabs forces.

The U.S. also tried to mediate and Nasser agreed to send his vice-president to Washington to explore a diplomatic settlement. The meeting did not happen because Israel launched its offensive. Some analysts suggest that Nasser took actions aimed at reaping political gains, which he knew carried a high risk of precipitating military hostilities. Nasser's willingness to take such risks was based on his fundamental underestimation of Israel's capacity for independent and effective military action. Abba Eban, the Israeli Foreign Minister, also flew to Washington to ascertain what position the U.S. administration was taking on the developing crises. News reached him in Washington that Egypt was planning a attack, which resulted in communication between the United States and the Soviet Union, since Egypt was regarded as a Soviet proxy. The U.S. told the Soviet Union that a global crises could result if Israel was attacked.

ref>Oren, 2002, pp. 102-103.</ref> At 2:30 a.m. on May 27, Soviet Ambassador to Egypt Dimitri Pojidaev knocked on Nasser's door and read him a personal letter from Kosygin in which he said, "We don't want Egypt to be blamed for starting a war in the Middle East. If you launch that attack, we cannot support you." The attack was canceled.

Within Israel's political leadership, it was decided that if the U.S. would not act, and if the UN could not act, then Israel would have to act. On June 1, Moshe Dayan was made Israeli Defense Minister, and on June 3, the Johnson administration gave an ambiguous statement; Israel continued to prepare for war. Israel's attack against Egypt on June 5, began what would later be dubbed the Six-Day War. Martin van Creveld explains the impetus to war: "…the concept of 'defensible borders' was not even part of the IDFs own vocabulary. Anyone who will look for it in the military literature of the time will do so in vain. Instead, Israel's commanders based their thought on the 1948 war and, especially, their 1956 triumph over the Egyptians in which, from then Chief of Staff Dayan down, they had gained their spurs. When the 1967 crisis broke they felt certain of their ability to win a 'decisive, quick and elegant' victory, as one of their number, General Haim Bar Lev, put it, and pressed the government to start the war as soon as possible."[34]

The combatant armies

On the eve of the war Egypt massed around 100,000 of its 160,000 troops in the Sinai, including all of its seven divisions (four infantry, two armored, and one mechanized), as well as four independent infantry and four independent armored brigades. No less then a third of them were veterans of Egypt intervention into Yemen Civil War and another third were reservists. These forces had 950 tanks, 1,100 APCs, and more then 1,000 artillery pieces. At the same time, some of Egyptian troops (15,000-20,000) were still fighting in Yemen.[35] Nasser was always ambivalent about taking this military action.

Jordan's army had a total strength of 55,000,[36] but it too was embroiled in the fighting in Yemen. Syria's army had 75,000 troops.[37]

The Israeli army had a total strength, including reservists, of 264,000, though of course this number could not be sustained, as the reservists were vital to civilian life.[38] James Reston, writing in the New York Times on May 23, 1967, noted, "In discipline, training, morale, equipment and general competence his [Nasser's] army and the other Arab forces, without the direct assistance of the Soviet Union, are no match for the Israelis… Even with 50,000 troops and the best of his generals and air force in Yemen, he has not been able to work his way in that small and primitive country, and even his effort to help the Congo rebels was a flop."[39]

On June 1, Israeli minister of defense Moshe Dayan called Chief of Staff Yitzhak Rabin and the General Officer Commanding, Southern Command Brigadier General Yeshayahu Gavish to present plans to be implemented against Egypt. Rabin had formulated a plan in which Southern Command would fight its way to the Gaza Strip and then hold the territory and its people hostage until Egypt agreed to reopen the Straits of Tiran while Gavish had a more comprehensive plan that called for the destruction of Egyptian forces in the Sinai. Rabin favored Gavish's plan, which was then endorsed by Dayan with the caution that a simultaneous offensive against Syria should be avoided.[40]

Warfare

Preliminary air attack

Israel's first and most important move was a preemptive attack on the Egyptian Air Force. It was by far the largest and the most modern of all the Arab air forces, consisting of about 450 combat aircraft, all of them Soviet-built and relatively new.

Of particular concern to the Israelis were the 30 Tu-16 Badger medium bombers, capable of inflicting heavy damage on Israeli military and civilian centers.[41] On June 5, at 7:45 Israeli time, as civil defense sirens sounded all over Israel, the Israeli Air Force launched Operation Focus (Moked). All but twelve of its nearly 200 operational jets[42] left the skies of Israel in a mass attack against Egypt's airfields.[43] Egyptian defensive infrastructure was extremely poor, and no airfields were yet equipped with armored bunkers capable of protecting Egypt's warplanes in the event of an attack. The Israeli warplanes headed out over the Mediterranean before turning toward Egypt. Meanwhile, the Egyptians hindered their own defense by effectively shutting down their entire air defense system: they were worried that rebel Egyptian forces would shoot down the plane carrying Field Marshal Amer and Lt-Gen. Sidqi Mahmoud, who were en route from al Maza to Bir Tamada in the Sinai to meet the commanders of the troops stationed there. In the end it did not make a great deal of difference, as the Israeli pilots came in below Egyptian radar cover and well below the lowest point at which its SA-2 surface-to-air missile batteries could bring down an aircraft.[44] The Israelis employed a mixed attack strategy; bombing and strafing runs against the planes themselves, and tarmac-shredding penetration bombs dropped on the runways that rendered them unusable, leaving any undamaged planes unable to take off and therefore helpless targets for later Israeli waves. The attack was more successful than expected, catching the Egyptians by surprise, the attack destroying virtually all of the Egyptian Air Force on the ground with few Israeli casualties. Over 300 Egyptian aircraft were destroyed and 100 Egyptian pilots were killed.[45] The Israelis lost 19 of their planes, and most of these were operational losses (i.e. mechanical failure, accidents, etc). The attack guaranteed Israeli air superiority for the rest of the war.

Before the war, Israeli pilots and ground crews trained extensively in rapid refitting of aircraft returning from sorties, enabling a single aircraft to sortie up to four times a day (as opposed to the norm in Arab air forces of one or two sorties per day). This enabled the IAF to send several attack waves against Egyptian airfields on the first day of the war, overwhelming the Egyptian Air Force. This also has contributed to the Arab belief that the IAF was helped by foreign air forces. The Arab air forces themselves were aided by pilots from the Pakistan Air Force.

Following the success of the initial attack waves against the major Egyptian airfields, subsequent attacks were made later in the day against secondary Egyptian airfields as well as Jordanian, Syrian, and even Iraqi fields. Throughout the war, Israeli aircraft continued strafing airfield runways to prevent their return to usability.

Gaza Strip and Sinai Peninsula

The Egyptian forces consisted of seven divisions: four armored, two infantry, and one mechanized infantry. Overall, Egypt had around 100,000 troops and 900-950 tanks in the Sinai, backed by 1,100 APCs and 1000 artillery pieces.[46] This arrangement was based on the Soviet doctrine, where mobile armor units at strategic depth provide a dynamic defense while infantry units engage in defensive battles.

Israeli forces concentrated on the border with Egypt included six armored brigades, one infantry brigade, one mechanized infantry brigade, three paratrooper brigades and 700 tanks giving a total of around 70,000 men, organized in three armored divisions. The Israeli plan was to surprise the Egyptian forces in both timing (the preemptive attack exactly coinciding with the IAF strike on Egyptian airfields), location (attacking via northern and central Sinai routes, as opposed to the Egyptian expectations of a repeat of the 1956 war, when the IDF attacked via the central and southern routes), and method (using a combined-force flanking approach, rather than direct tank assaults).

The northernmost Israeli division, consisting of three brigades and commanded by Major General Israel Tal, one of Israel's most prominent armor commanders, advanced slowly through the Gaza Strip and El-Arish, which were not heavily protected.

The central division (Maj. Gen. Avraham Yoffe) and the southern division (Maj. Gen. Ariel Sharon), however, entered the heavily defended Abu-Ageila-Kusseima region. Egyptian forces there included one infantry division (the 2nd), a battalion of tank destroyers and a tank regiment.

Sharon initiated an attack, precisely planned, coordinated, and carried out. He sent two of his brigades to the north of Um-Katef, the first one to break through the defenses at Abu-Ageila to the south, and the second to block the road to El-Arish and to encircle Abu-Ageila from the east. At the same time, a paratrooper force was dispatched to the rear of the defensive positions and destroyed the artillery, preventing it from engaging Israeli armor and infantry. Combined forces of armor, paratroopers, infantry, artillery, and combat engineers then attacked the Egyptian position from the front, flanks and rear, cutting the enemy off. The breakthrough battles, which were in sandy areas and minefields, continued for three and a half days until Abu-Ageila fell.

Many of the Egyptian units remained intact and could have tried to prevent the Israelis from reaching the Suez Canal or engaged in combat in the attempt to reach the canal. However, when the Egyptian Minister of Defense, Field Marshal Abdel Hakim Amer heard about the fall of Abu-Ageila, he panicked and ordered all units in the Sinai to retreat. This order effectively meant the defeat of Egypt.

Due to the Egyptians' retreat, the Israeli High Command decided not to pursue the Egyptian units but rather to bypass and destroy them in the mountainous passes of West Sinai. Therefore, during the following two days (June 6 and June 7), all three Israeli divisions (Sharon and Tal were reinforced by an armored brigade each) rushed westwards and reached the passes. Sharon's division first went southward then westward to Mitla Pass. It was joined there by parts of Yoffe's division, while its other units blocked the Gidi Pass. Tal's units stopped at various points down the length of the Suez Canal.

Israel's blocking action was only partially successful. Only the Gidi pass was captured before the Egyptians approached it, but at other places, Egyptian units managed to pass through and cross the canal to safety. Nevertheless, the Israeli victories were impressive. In four days of operations, Israel defeated the largest and most heavily equipped Arab army, leaving numerous points in the Sinai littered with hundreds of burning or abandoned Egyptian vehicles and military equipment.

On June 8, Israel had completed the capture of the Sinai by sending infantry units to Ras-Sudar on the western coast of the peninsula. Sharm El-Sheikh, at its southern tip, had already been taken a day earlier by units of the Israeli Navy.

Several tactical elements made the swift Israeli advance possible: first, the complete air superiority of the Israeli Air Force over its Egyptian counterpart; second, the determined implementation of an innovative battle plan; and third, the lack of coordination among Egyptian troops. These would prove to be decisive elements on Israel's other fronts as well.

West Bank

Jordan was reluctant to enter the war. Some claim that Nasser used the obscurity of the first hours of the conflict to convince Hussein that he was victorious; he claimed as evidence a radar sighting of a squadron of Israeli aircraft returning from bombing raids in Egypt which he claimed to be Egyptian aircraft en route to attacking Israel. One of the Jordanian brigades stationed in the West Bank was sent to the Hebron area in order to link with the Egyptians. Hussein decided to attack.

Prior to the war, Jordan's forces included 11 brigades totaling some 55,000 troops, equipped by some 300 modern Western tanks. Of these, 9 brigades (45,000 troops, 270 tanks, 200 artillery pieces) were deployed in the West Bank, including elite armored 40th, and 2 in the Jordan Valley. The Arab Legion was a long-term-service, professional army relatively well-equipped and well-trained. Furthermore, Israeli post-war briefings claimed that the Jordanian staff acted professionally as well, but was always left "half a step" behind by the Israeli moves. The tiny Royal Jordanian Air Force consisted of only 24 U.K. Hawker Hunter fighters. According to the Israelis, U.K. Hawker Hunter was essentially on par with French Dassault Mirage III—IAF's best aircraft.[47]

Against Jordan's forces on West Bank Israel deployed about 40,000 troops and 200 tanks (8 brigades). Israeli Central Command forces consisted of five brigades. The first two were permanently stationed near Jerusalem and were called the Jerusalem Brigade and the mechanized Harel Brigade. Mordechai Gur's 35th paratrooper brigade was summoned from the Sinai front. An armored brigade was allocated from the General Staff reserve and brought to the Latrun area. The 10th armored brigade was stationed north of Samaria. The Israeli Northern Command provided a division (3 brigades) led by Maj. Gen. Elad Peled, which was stationed to the north of Samaria, in the Jezreel Valley.

The IDF's strategic plan was to remain on the defensive along the Jordanian front, to enable focus in the expected campaign against Egypt. However, on the morning of June 5, Jordanian forces made thrusts in the area of Jerusalem, occupying Government House used as the headquarters for the UN observers and shelled the Israeli (western) part of the city. Units in Qalqiliya fired in the direction of Tel-Aviv. The Royal Jordanian Air Force attacked Israeli airfields. Both air and artillery attacks caused little damage. Israeli units were scrambled to attack Jordanian forces in the West Bank. In the afternoon of that same day, Israeli Air Force (IAF) strikes destroyed the Royal Jordanian Air Force. By the evening of that day, the Jerusalem infantry brigade moved south of Jerusalem, while the mechanized Harel and Gur's paratroopers encircled it from the north.

On June 6, the Israeli units attacked: The reserve paratroop brigade completed the Jerusalem encirclement in the bloody Battle of the Ammunition Hill. The infantry brigade attacked the fortress at Latrun capturing it at daybreak, and advanced through Beit Horon towards Ramallah. The Harel brigade continued its push to the mountainous area of north-west Jerusalem, linking the Mount Scopus campus of Hebrew University with the city of Jerusalem. By the evening, the brigade arrived in Ramallah. The IAF detected and destroyed the 60th Jordanian Brigade en-route from Jericho to reinforce Jerusalem.

In the north, one battalion from Peled's division was sent to check Jordanian defenses in the Jordan Valley. A brigade belonging to Peled's division captured Western Samaria, another captured Jenin, and the third (equipped with light French AMX-13s) engaged Jordanian M48 Patton main battle tanks to the east.

On June 7, heavy fighting ensued. Gur's paratroopers entered the Old City of Jerusalem via the Lion's Gate, and captured the Western Wall and the Temple Mount. The Jerusalem brigade then reinforced them, and continued to the south, capturing Judea, Gush Etzion, and Hebron. The Harel brigade proceeded eastward, descending to the Jordan River. In Samaria, one of Peled's brigades seized Nablus; then it joined one of Central Command's armored brigades to fight the Jordanian forces which held the advantage of superior equipment and were equal in numbers to the Israelis.

Again, the air superiority of the IAF proved paramount as it immobilized the enemy, leading to its defeat. One of Peled's brigades joined with its Central Command counterparts coming from Ramallah, and the remaining two blocked the Jordan river crossings together with the Central Command's 10th (the latter crossed the Jordan river into the East Bank to provide cover for Israeli combat engineers while they blew the bridges, but was quickly pulled back because of American pressure).

Golan Heights

During the evening of June 5, Israeli air strikes destroyed two thirds of the Syrian Air Force, and forced the remaining third to retreat to distant bases, without playing any further role in the ensuing warfare. A minor Syrian force tried to capture the water plant at Tel Dan (the subject of a fierce escalation two years earlier). Several Syrian tanks are reported to have sunk in the Jordan river. In any case, the Syrian command abandoned hopes of a ground attack, and began a massive shelling of Israeli towns in the Hula Valley instead.

June 7 and 8 passed in this way. At that time, a debate had been going on in the Israeli leadership whether the Golan Heights should be assailed as well. Military advice was that the attack would be extremely costly, as it would be an uphill battle against a strongly fortified enemy. The western side of the Golan Heights consists of a rock escarpment that rises 500 meters (1700 ft) from the Sea of Galilee and the Jordan River to a more gently sloping plateau. Moshe Dayan believed such an operation would yield losses of 30,000, and opposed it bitterly. Levi Eshkol, on the other hand, was more open to the possibility of an operation in the Golan Heights, as was the head of the Northern Command, David Elazar, whose unbridled enthusiasm for and confidence in the operation may have eroded Dayan's reluctance. Eventually, as the situation on the Southern and Central fronts cleared up, Moshe Dayan became more enthusiastic about the idea, and he authorized the operation.

The Syrian army consisted of about 75,000 men grouped in 9 brigades, supported by an adequate amount of artillery and armor. Israeli forces used in combat consisted of two brigades (one armored led by Albert Mandler and the Golani Brigade) in the northern part of the front, and another two (infantry and one of Peled's brigades summoned from Jenin) in the center. The Golan Heights' unique terrain (mountainous slopes crossed by parallel streams every several kilometers running east to west), and the general lack of roads in the area channeled both forces along east-west axes of movement and restricted the ability of units to support those on either flank. Thus the Syrians could move north-south on the plateau itself, and the Israelis could move north-south at the base of the Golan escarpment. An advantage Israel possessed was the excellent intelligence collected by Mossad operative Eli Cohen (who was captured and executed in Syria in 1965) regarding the Syrian battle positions.

The IAF, which had been attacking Syrian artillery for four days prior to the attack, was ordered to attack Syrian positions with all its force. While the well-protected artillery was mostly undamaged, the ground forces staying on the Golan plateau (6 of the 9 brigades) became unable to organize a defense. By the evening of June 9, the four Israeli brigades had broken through to the plateau, where they could be reinforced and replaced.

On the next day, June 10, the central and northern groups joined in a pincer movement on the plateau, but that fell mainly on empty territory as the Syrian forces fled. Several units joined by Elad Peled climbed to the Golan from the south, only to find those positions mostly empty as well. During the day, the Israeli units stopped after obtaining maneuver room between their positions and a line of volcanic hills to the west. To the east, the ground terrain is an open gently sloping plain. This position later became the cease-fire line known as the "Purple Line."

War in the air

During the Six-Day War, the IAF demonstrated the importance of air superiority during the course of a modern conflict, especially in a desert theater. Following the IAF's preliminary air attack, beginning during sunrise (as it placed the sun behind the attacking aircraft giving them a tactical advantage), it was able to thwart and harass the Arab air forces and to grant itself air superiority over all fronts; it then complemented the strategic effect of their initial strike by carrying out tactical support operations. Of particular interest was the destruction of the Jordanian 60th armored brigade near Jericho and the attack on the Iraqi armored brigade which was sent to attack Israel through Jordan.

In contrast, the Arab air forces never managed to mount an effective attack: Attacks of Jordanian fighters and Egyptian TU-16 bombers into the Israeli rear during the first two days of the war were not successful and led to the destruction of the aircraft (Egyptian bombers were shot down while Jordan's fighters were destroyed during the attack on the airfield).

Another important factor contributed to the Israeli aerial victory was that there were numerous disillusioned Arabic pilots who had defected with their MiGs to Israel prior to the outbreak of the conflict, and Israeli capitalized on this by test flying the MiGs to the maximum, thus giving Israeli pilots great advantage over their opponents. Notable Arab defections included:

- Iraqi Captain Munir Redfa, 3 MiG-21F-13 and at least 6 MiG-17F Algerian pilots were captured by Israel after landing their aircraft at Israeli el-Arish Air Base by mistake, one of the captured Algerian pilot asked and was granted political asylum in the west, while the rest were repatriated.

- On January 19, 1964, Egyptian pilot Mahmud Abbas Hilmi defected from el-Arish Air Base to Hatzor, in Israel in his Yakovlev Yak-11 trainer.

- In 1966, Iraqi Captain Munir Redfa flew his MiG-21 F-13 to Israel.

On June 6, the second day of the war, King Hussein and Nasser declared that American and British aircraft took part in the Israeli attacks. This announcement was intercepted by the Israelis and turned into a media frenzy. This became known as "The Big Lie" in American and British circles.

War at sea

War at sea was extremely limited. Movements of both Israeli and Egyptian vessels are known to have been used to intimidate the other side, but neither side directly engaged the other at sea. The only moves that yielded any result were the use of six Israeli frogmen in Alexandria harbor (they were captured, having sunk a minesweeper), and the Israeli light boat crews that captured the abandoned Sharm El-Sheikh on the southern tip of the Sinai Peninsula on June 7.

On June 8, USS Liberty, a United States Navy electronic intelligence vessel sailing 13 nautical miles off al-Arish (just outside Egypt's territorial waters), was attacked by Israeli air and sea forces, nearly sinking the ship and causing heavy casualties. Israel claimed the attack was a case of mistaken identity, apologized for the mistake, and paid restitution to the victims or their families. The truth of the Israeli claim is still debated.

Conclusion of conflict and post-war situation

By June 10, Israel had completed its final offensive in the Golan Heights and a ceasefire was signed the following day. Israel had seized the Gaza Strip, the Sinai Peninsula, the West Bank of the Jordan River (including East Jerusalem), and the Golan Heights. Overall, Israel's territory grew by a factor of 3, including about one million Arabs placed under Israel's direct control in the newly captured territories. Israel's strategic depth grew to at least 300 kilometers in the south, 60 kilometers in the east and 20 kilometers of extremely rugged terrain in the north, a security asset that would prove useful in the Yom Kippur War six years later.

The political importance of the 1967 War was immense; Israel demonstrated that it was not only able, but also willing to initiate strategic strikes that could change the regional balance. Egypt and Syria learned tactical lessons, but perhaps not the strategic ones, and would launch an attack in Yom Kippur War of 1973 in an attempt to reclaim their lost territory.

According to Chaim Herzog,

- On June 19, 1967, the National Unity Government [of Israel] voted unanimously to return the Sinai to Egypt and the Golan Heights to Syria in return for peace agreements. The Golans would have to be demilitarized and special arrangement would be negotiated for the Straits of Tiran. The government also resolved to open negotiations with King Hussein of Jordan regarding the Eastern border.[48]

The Israeli decision was to be conveyed to the Arab nations by the United States. The U.S. was informed of the decision, but not that it was to transmit it. There is no evidence of receipt from Egypt or Syria, and some historians claim that they may have never received the offer.[49]

Later, the Khartoum Arab Summit resolved that there would be "no peace, no recognition and no negotiation with Israel." However, as Avraham Sela notes, the Khartoum conference effectively marked a shift in the perception of the conflict by the Arab states away from one centered on the question of Israel's legitimacy toward one focusing on territories and boundaries and this was underpinned on November 22, when Egypt and Jordan accepted UN Resolution 242.[50]

The June 19, cabinet decision did not include the Gaza Strip, and left open the possibility of Israel permanently acquiring parts of the West Bank. On June 25-27, Israel incorporated East Jerusalem together with areas of the West Bank to the north and south into Jerusalem's new municipal boundaries.

Yet another aspect of the war touches on the population of the captured territories: of about one million Palestinians in the West Bank, 300,000 fled to Jordan, where they contributed to the growing unrest. The other 600,000 remained. In the Golan Heights, an estimated 80,000 Syrians fled. Only the inhabitants of East Jerusalem and the Golan Heights were allowed to receive limited Israeli residency rights, as Israel annexed these territories in the early 1980s. Both Jordan and Egypt eventually withdrew their claims to West Bank and Gaza (the Sinai was returned on the basis of Camp David Accords of 1978 and the question of the Golan Heights is still being negotiated with Syria). After Israeli conquest of these newly acquired territories a large settlement effort was launched to secure Israel's permanent foothold. There are now hundreds of thousands of Israeli settlers in these territories, although the Israeli settlements in Gaza were evacuated and destroyed in August 2005, as a part of Israel's unilateral disengagement plan.

The casualties of the war, far from Israel's anticipated heavy estimates, were quite low, with 338 soldiers lost on the Egyptian front, 300 on the Jordanian front, and 141 on the Syrian front. Egypt lost 80 percent of its military equipment, 10,000 soldiers and 1,500 officers killed, 5,000 soldiers and 500 officers captured,[51] and 20,000 wounded.[52] Jordan suffered 6,000-7,000 killed and probably around 12,000 to 20,000 wounded.[53] Syria lost 2,500 dead and 5,000 wounded; half the tanks and almost all the artillery positioned in the Golan Heights were destroyed.[54] The official count of Iraqi casualties was 10 killed and about thirty wounded.[55]

The 1967 War also laid the foundation for future discord in the region—as on November 22, 1967, the UN Security Council adopted Resolution 242, the "land for peace" formula, which called for Israeli withdrawal "from territories occupied" in 1967 in return for "the termination of all claims or states of belligerency."

The framers of Resolution 242 recognized that some territorial adjustments were likely and deliberately did not include words "all" or "the" in the official English language version of the text when referring to "territories occupied" during the war, although it is present in other, notably French, Spanish, and Russian versions. It recognized the right of "every state in the area"—thus Israel in particular—"to live in peace within secure and recognized boundaries free from threats or acts of force." Israel returned the Sinai to Egypt in 1978, after the Camp David Accords, and disengaged completely from the Gaza Strip in the summer of 2005, though its army frequently re-enters Gaza for military operations.

The aftermath of the war is also of religious significance. Under Jordanian rule, Jews and many Christians were forbidden from entering the Old City of Jerusalem, which included the Western Wall, Judaism's holiest site. Jewish sites were not maintained, and their cemeteries had been desecrated. After the annexation to Israel, each religious group was granted administration over their holy sites. Despite the Temple Mount's importance in Jewish tradition, the al-Aqsa Mosque is under sole administration of a Muslim Waqf, and Jews are barred from conducting services there.

Accusations and controversial claims

The dramatic events of the Six Day War have given rise to a number of accusations of atrocities and controversial claims and theories.

Israel Defense Forces and Egyptian prisoners of war

In an August 16, 1995, interview for Israel Radio, Aryeh Yitzhaki of Bar-Ilan University, who had worked previously in the IDF history department, accused IDF units of killing up to 1,000 Egyptians who had abandoned their weapons and fled into the desert during the war. The allegations received widespread attention in Israel and throughout the world. However, it emerged subsequently that Yitzhaki was a member of Rafael Eitan's Tsomet Party and former employer Meir Pa'il speculated that Yitzhaki had an ulterior motive in seeking to divert public attention away from revelations by retired general Arye Biro concerning his involvement in the killing of 49 POWs in the 1956 war.

Although Yitzkhaki’s claim that up to 1,000 prisoners had been killed was not substantiated, in an ensuing highly-controversial national debate in Israel, more soldiers came forward to say that they had witnessed the execution of unarmed prisoners and a long-suppressed public reckoning began.

A June 11, 1967, general-command IDF order specifically forbade killing prisoners, clarifying the official Israeli position. However, no official Israeli documents that would allow the scale of the killings to be accurately assessed have been released.

According to a New York Times report of September 21, 1995, the Egyptian government announced that it had discovered two shallow mass graves in the Sinai at El Arish containing the remains of 30-60 Egyptian prisoners shot by Israeli soldiers during the 1967 war. Israel reportedly offered compensation to the families of the victims.

According to Israeli official records, 4,338 Egyptian soldiers were captured by IDF. Only 11 Israeli soldiers were taken prisoners by Egyptian forces. Exchanges of those prisoners were completed on January 23, 1968.

Alleged American and British Support

Historians such as Michael Oren have argued that by falsely accusing the United States and Britain of directly helping the Israelis the Arab leaders were attempting to secure active Soviet military assistance for themselves. The Soviets, however, knew that these claims of foreign assistance to Israel were groundless and notified Arab diplomats in Moscow of that fact. Yet even though the Soviet government disbelieved these accusations, Soviet media continued to quote them, thereby strengthening the credibility of the reports. In reaction to these claims, Arab oil-producing countries announced an oil embargo.

In a 1993 interview, U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara revealed that the U.S. 6th Fleet Carrier battle group, on a training exercise near Gibraltar was re-positioned towards the eastern Mediterranean to defend Israel if necessary, causing a crisis between the U.S. and USSR. McNamara did not explain how the crisis was resolved.

In his book Six Days, BBC journalist Jeremy Bowen claims that during the crisis, Israeli ships and planes carried British and American military arms reserves from British soil.

Soviet instigation

There are theories that the entire 1967 War was a botched attempt by the Soviet Union to create tensions between West Germany and Arab countries by highlighting West Germany's support for Israel.

In a 2003 article Isabella Ginor detailed Soviet GRU documents proposing such a plan and further detailing faulty intelligence fed to Egypt claiming troop buildups near the Golan Heights in Syria.[56]

Footnotes

- ↑ Jewish Virtual Library. UN Security Council Resolution 242. Retrieved June 1, 2007.

- ↑ US Dept of State. Road map to a Permanent Two State Solution to the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict. Retrieved June 1, 2007.

- ↑ Rabil, 2003, pp. 17-18.

- ↑ Koboril and Glantz, 1998, pp. 129-130.

- ↑ Bowen, 2003, p. 26 (citing Amman Cables 1456, 1457, December 11 1966, National Security Files (Country File: Middle East), LBJ Library (Austin, Texas), Box 146).

- ↑ Hussein, 1969, p. 25.

- ↑ Bowen, 2003, pp. 23-30.

- ↑ Prittie, 1969, pp. 245.

- ↑ The Times. "King Husain orders nation-wide military service." Monday, 21 November 1966; pg. 8; Issue 56794; col D.

- ↑ Jewish Virtual Library. United Nations Security Council Resolution 228. Retrieved June 1, 2007.

- ↑ U.S. Dept of State. Telegram From the Embassy in Jordan to the Department of State, Amman, May 18 1967. Retrieved June 1, 2007.

- ↑ Hajjar, Sami G. "The Isreali-Syria Track," Middle East Policy Council Journal, Volume VI, February 1999, Number 3.

- ↑ Rikhye, 1980, p. 143 (author interview).

- ↑ Aloni, 2001, p. 31.

- ↑ Bowen, 2003, pp. 30-31

- ↑ 'Jets and tanks in fierce clash by Israel and Syria', The Times, Saturday, 8 April 1967; pg. 1; Issue 56910; col A.

- ↑ 'Warning by Israelis Stresses Air Power,' New York Times, 12 May 1967, p. 38.

- ↑ Oren, 2002, p. 51.

- ↑ Bregman, 2002, pp. 68-69.

- ↑ Rikhye, 1980, pp. 16-19.

- ↑ Oren, 2002, p. 72

- ↑ The United Nations. "First United Nations Emergency Force (UNEF I) - Background," Retrieved June 1, 2007.

- ↑ "Egypt Closes Gulf Of Aqaba To Israel Ships: Defiant move by Nasser raises Middle East tension," The Times. Tuesday, May 23, 1967; pg. 1; Issue 56948; col A.

- ↑ Quigely, 2005, p. 161.

- ↑ Christie, 1999, p. 104.

- ↑ Quigley, 1990, pp. 166-167.

- ↑ "Egypt and Jordan United Against Israel," BBC On this Day, Egypt and Jordan unite against Israel. Retrieved 24-03-2007.

- ↑ Mutawi, 2002, p. 16.

- ↑ Leibler, Isi (1972). The Case For Israel. Australia: The Executive Council of Australian Jewry, p. 60.

- ↑ Mutawi, 2002, p. 102.

- ↑ Seale, 1988, p.131 citing Stephens, 1971, p. 479.

- ↑ Eban, 1977, p. 371.

- ↑ Gelpi, 2002, p. 143.

- ↑ van Creveld, 2004, p. 21.

- ↑ Dawisha, "Intervention in Yemen," p. 59

- ↑ Mutawi, 2002, p. 42.

- ↑ Ehteshami and Hinnebusch, 1997, p. 76.

- ↑ Stone, 2004, p. 217.

- ↑ Reston, James Washington: Nasser's Reckless Maneuvers, New York Times. May 24, 1967, p. 46.

- ↑ Hammel, 1992, p. 153-152.

- ↑ Pollack, 2004, p. 58.

- ↑ Oren, 2002, p. 172

- ↑ Bowen, 2003, p. 99 (author interview with Moredechai Hod, 7 May 2002).

- ↑ Bowen, 2003, pp. 114-115

- ↑ Pollack, 2005, p. 474.

- ↑ Pollack, 2004, p. 59.

- ↑ Pollack, "Arabs at War," p. 293-294

- ↑ Herzog, Chaim Heroes of Israel p.253.

- ↑ Shlaim, 2001, p.254.

- ↑ Sela, 1997, p. 108.

- ↑ Hopwood, 1991, p. 76.

- ↑ Stone, 2004, p. 219.

- ↑ Pollack, 2004, p. 315.

- ↑ Stone, 2004, pp. 221-222.

- ↑ Makiya, 1998, p. 48.

- ↑ Ginor, Isabella. The Cold War's Longest Cover-Up: How and Why the USSR Instigated the 1967 War." Middle East Reveiw of International Affairs, Vol. 7, No. 3, September 2003.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Aloni, Shlomo. Arab-Israeli Air Wars 1947-1982. Oxford: Osprey Aviation, 2001 ISBN 1-84176-294-6

- Christie, Hazel. Law of the Sea. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1999 ISBN 0-7190-4382-4

- Bregman, Ahron. Israel's Wars: A History Since 1947. London: Routledge, 2002 ISBN 0-415-28716-2

- Bar-On, Mordechai, Morris, Benny and Golani, Motti. Reassessing Israel's Road to Sinai/Suez, 1956: A "Trialogue." In Gary A. Olson (Ed.). Traditions and Transitions in Israel Studies: Books on Israel, Volume VI (pp. 3-42). Albany: SUNY Press, 2002 ISBN 0-7914-5585-8

- Black, Ian. Israel's Secret Wars: A History of Israel's Intelligence Services. NY: Grove Weidenfeld, 1992 ISBN 0-8021-3286-3

- Bowen, Jeremy. Six Days: How the 1967 War Shaped the Middle East. London: Simon & Schuster, 2003 ISBN 0-7432-3095-7

- Cristol, A Jay . Liberty Incident: The 1967 Israeli Attack on the U.S. Navy Spy Ship. London: Brassey's Military Books, 2002 ISBN 1-57488-536-7

- Eban, Abba. Abba Eban: An Autobiography. NY: Random House, 1997 ISBN 0-394-49302-8

- Ehteshami, Anoushiravan and Hinnebusch, Raymond A. Syria & Iran: Middle Powers in a Penetrated Regional System. London: Routledge, 1997 ISBN 0-415-15675-0

- Finkelstein, Norman. Image and Reality of the Israel-Palestine Conflict. NY: Verso, 2003 ISBN 978-1859844427

- Gat, Moshe. Britain and the Conflict in the Middle East, 1964-1967: The Coming of the Six-Day War. NY: Praeger/Greenwood, 2003 ISBN 0-275-97514-2

- Gelpi, Christopher. Power of Legitimacy: Assessing the Role of Norms in Crisis Bargaining. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2002 ISBN 0-691-09248-6

- Hammel, Eric (October 2002). Sinai air strike:June 5 1967. Military Heritage 4 (2): 68–73.

- Hammel, Eric. Six Days in June: How Israel Won the 1967 Arab-Israeli War. NY: Simon & Schuster, 1993 ISBN 0-7434-7535-6

- Hussein of Jordan. My "War" with Israel. London: Peter Owen, 1969 ISBN 0-7206-0310-2

- Hopwood, Derek. Egypt: Politics and Society. London: Routledge, 1991 ISBN 0-415-09432-1

- Koboril, Iwao and Glantz, Michael H. Central Eurasian Water Crisis. Tokyo: United Nations University Press, 1998 ISBN 92-808-0925-3

- Makiya, Kanan. Republic of Fear: The Politics of Modern Iraq. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1998 ISBN 0-520-21439-0

- Morris, Benny. Israel's Border Wars, 1949-1956. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997 ISBN 0-19-829262-7

- Mutawi, Samir. Jordan in the 1967 War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002 ISBN 0-521-52858-5

- Oren, Michael. Six Days of War. NY: Oxford University Press, 2002 ISBN 0-19-515174-7

- Phythian, Mark. The Politics of British Arms Sales Since 1964. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2001 ISBN 978-0719059070

- Podeh, Elie (Winter, 2004). The Lie That Won't Die: Collusion, 1967. Middle East Quarterly 11 (1).

- Pollack, Kenneth. Arabs at War: Military Effectiveness, 1948-1991. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2004 ISBN 0-8032-8783-6

- Pollack, Kenneth. Air Power in the Six-Day War. The Journal of Strategic Studies. 28(3), 471-503 (2005)

- Prior, Michael Zionism and the State of Israel: A Moral Inquiry. London: Routledge, 1999 ISBN 0-415-20462-3

- Quigley, John B. Case for Palestine: An International Law Perspective. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005 ISBN 0-8223-3539-5

- Quigley, John B. Palestine and Israel: A Challenge to Justice. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1990 ISBN 0-8223-1023-6

- Rabil, Robert G. Embattled Neighbors: Syria, Israel, and Lebanon. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2003 ISBN 1-58826-149-2

- Rezun, Miron. Iran and Afghanistan. In A. Kapur (Ed.). Diplomatic Ideas and Practices of Asian States (pp. 9-25). Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers, 1990 ISBN 90-04-09289-7

- Rikhye, Indar Jit. The Sinai Blunder. London: Routledge, 1980 ISBN 0-7146-3136-1

- Rubenberg, Cheryl A. Israel and the American National Interest, Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1989 ISBN 0-252-06074-1

- Seale, Patrick. Asad: The Struggle for Peace in the Middle East. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1988 ISBN 0-520-06976-5

- Segev, Tom Israel in 1967 Jerusalem: Keter, 2005 ISBN 965-07-1370-0

- Sela, Avraham. The Decline of the Arab-Israeli Conflict: Middle East Politics and the Quest for Regional Order. SUNY Press, 1997 ISBN 0-7914-3537-7

- Shlaim, Avi The Iron Wall: Israel and the Arab World NY: W. W. Norton & Company, 2001 ISBN 0-393-32112-6

- Smith, Grant. Deadly Dogma. Washin gton, DC: Institute for Research: Middle Eastern Policy, 2006 ISBN 0-9764437-4-0

- Stephens, Robert H. Nasser: A Political Biography. London: Allen Lane/The Penguin Press, 1971 ISBN 0-7139-0181-0

- Stone, David. Wars of the Cold War. London: Brassey's, 2004 ISBN 1-85753-342-9

- van Creveld, Martin. Defending Israel: A Controversial Plan Toward Peace. NY: Thomas Dunne Books, 2004 ISBN 0-312-32866-4

External links

All links retrieved January 29, 2023.

- Deadly Dogma #1 Strike First by Grant F. Smith. Published by the Washington D.C. based Institute for Research: Middle Eastern Policy. (March 2006).

- How The USSR Planned To Destroy Israel in 1967 by Isabella Ginor. Published by Middle East Review of International Affairs (MERIA) Journal Volume 7, Number 3 (September 2003).

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.