West Germany

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

West Germany (in German Westdeutschland) was the common English name for the former Federal Republic of Germany, from its founding on May 24, 1949, to October 2, 1990.

With an area of 95,976 square miles (248,577 square kilometers), or slightly smaller than Oregon in the United States, West Germany was bordered on the north by the North Sea, Denmark, and the Baltic Sea; on the east by the former East Germany and the Czech Republic; on the south by Austria and Switzerland; and on the west by France, Luxembourg, Belgium, and the Netherlands.

The Federal Republic of Germany was established after World War II in the zones occupied by the United States, United Kingdom, and France (excluding Saarland) on May 24, 1949. It consisted of 10 states‚ÄĒBaden-Wurttemberg, Bayern, Bremen, Hamburg, Hessen, Niedersachsen, Nordrhein-Westfalen, Rheinland-Pfalz, Saarland, Schleswig-Holstein, as well as the western part of Berlin. Bonn, the home town of the first chancellor Konrad Adenauer, became the capital.

On May 5, 1955, West Germany was declared "fully sovereign." The British, French and U.S. militaries remained in the country, just as the Soviet Army remained in East Germany. Four days after becoming "fully sovereign" in 1955, West Germany joined NATO. The U.S. retained an especially strong presence in West Germany, acting as a deterrent in case of a Soviet invasion.

The foundation for the influential position held by Germany today was laid during the "economic wonder" Wirtschaftswunder of the 1950s, when West Germany rose from the massive destruction wrought by World War II to become home to the world's fourth largest economy again.

Following the initial opening of sections of the Berlin Wall on November 9, 1989, in elections held on March 18, 1990, the governing party, the Socialist Unity Party of Germany, lost its majority in the East German parliament. On August 23, the Volkskammer decided that the territory of the Republic would accede to the ambit claim of the Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany. On October 3, 1990, the German Democratic Republic officially ceased to exist.

History

After the German military leaders unconditionally surrendered to Allied forces on May 8, 1945, Germany was devastated, with about 25 percent of the country's housing damaged beyond use. Factories and transport ceased to function, soaring inflation undermined the currency, food shortages meant city dwellers starved, while millions of homeless German refugees flooded west from the former eastern provinces. Sovereignty was in the hands of the victorious allied nations. Everything had to be rebuilt.

Four occupation zones

At the Potsdam Conference in August 1945, the Allies divided Germany into four military occupation zones ‚Äď French in the southwest, British in the northwest, United States in the south, and Soviet in the east. The former (1919-1937) German provinces east of the Oder-Neisse line (East Prussia, Eastern Pomerania and Silesia) were transferred to Poland, effectively shifting the country westward. Roughly 15 million ethnic Germans suffered terrible hardships in the years 1944 to 1947 during the flight and expulsion from the eastern German territories and the Sudetenland.

The intended governing body of Germany was called the Allied Control Council. The commanders-in-chief exercised supreme authority in their respective zones and acted in concert on questions affecting the whole country. Berlin, which lay in the Soviet (eastern) sector, was also divided into four sectors with the Western sectors later becoming West Berlin and the Soviet sector becoming East Berlin, the capital of East Germany.

A key item in the occupiers' agenda was denazification. Toward this end, the swastika and other outward symbols of the Nazi regime were banned, and a Provisional Civil Ensign was established as a temporary German flag. A strict non-fraternization policy was adhered to by General Eisenhower and the War department, although this was lifted in stages. The Allies tried at N√ľrnberg 22 Nazi leaders, all but three of whom were convicted, and 12 were sentenced to death.

Industrial disarmament

The initial post-surrender policy of the Western powers, known as the Morgenthau Plan proposed by Henry Morgenthau, Jr., was to involve abolition of the German armed forces as well as all munitions factories and civilian industries that could support them. The first plan, from March 29, 1946, stated that German heavy industry was to be lowered to 50 percent of its 1938 levels by the destruction of 1500 listed manufacturing plants. The first plan was subsequently followed by a number of new ones, the last signed in 1949. By 1950, after the virtual completion of the by the then much watered-out plans, equipment had been removed from 706 manufacturing plants in the west and steel production capacity had been reduced by 6,700,000 tons. Meanwhile, the Soviet Union engaged in a massive dismantling campaign in its occupation zone, much more intensive than that effected by the Western powers. It was realized that this alienated the German workers from the communist cause, but it was decided that the desperate economic situation in the Soviet Union took priority to alliance building. This was the beginning of the split of Germany.

Punishment

For several years following the surrender, Germans were starving, resulting in high mortality rates. Throughout all of 1945 the U.S. forces of occupation ensured that no international aid reached ethnic Germans. It was directed that all relief went to non-German displaced persons, liberated Allied POWs, and concentration camp inmates. As agreed by the Allies at the Yalta conference Germans were used as forced labor as part of the reparations to be extracted. By 1947 it is estimated that 4,000,000 Germans (both civilians and POWs) were being used as forced labor by the U.S., France, the United Kingdom and the Soviet Union. German prisoners were, for example, forced to clear minefields in France and the low countries. By December 1945 it was estimated by French authorities that 2,000 German prisoners were being killed or injured each month in accidents.

Beginning immediately after the German surrender and continuing for the next two years the U.S. pursued a vigorous program to harvest all technological and scientific know-how as well as all patents in Germany. John Gimbel comes to the conclusion, in his book Science Technology and Reparations: Exploitation and Plunder in Postwar Germany, that the "intellectual reparations" taken by the U.S. and the U.K. amounted to close to $10-billion.

France and the Saar region

Under the Monnet Plan, France wanted to ensure that Germany would never again be a threat, so attempted to gain economic control of the remaining German industrial areas with large coal and mineral deposits. The Rhineland, the Ruhr area and the Saar area (Germany's second largest center of mining and industry), Upper Silesia, had been handed over by the Allies to Poland for occupation at the Potsdam conference and the German population was being forcibly expelled. The Saarland came under French administration in 1947 as the Saar protectorate, but did, following a referendum, return it to Germany in January 1957, with economic reintegration with Germany occurring a few years later.

Political parties, Bizonia

When, in 1945, the occupation authorities permitted German political parties to contest elections, two Weimar Republic era leftist parties quickly revived‚ÄĒthe moderate Social Democratic Party (SPD) and the German Communist Party (KPD). The Christian Democratic Union (CDU), and the Christian Social Union (CSU) soon appeared, along with the Free Democratic Party (FDP), which favored a secular state and laissez-faire economic policies, as well as numerous smaller parties. Regional governmental units called L√§nder (singular Land), or states, were approved, and by 1947 states in the Western zones had freely elected parliamentary assemblies.

By 1947, the Soviet Union would not permit free, multiparty elections throughout the whole of Germany, so the Americans and British amalgamated German administrative units in their zones to create Bizonia, centered on the city of Frankfurt am Main. The purpose was to foster economic revival, but its federative structure became the model for the West German state.

The Social Democrats, who were committed to nationalization of basic industries and extensive government control over other aspects of the economy, and the Christian Democrats, who became oriented towards free-enterprise, quickly established themselves as the major political parties. The Christian Democrats, in March 1948, joined the laissez-faire Free Democrats.

The Marshall Plan

In September 6, 1946, the United States Secretary of State, James F. Byrnes, in a speech titled the Restatement of Policy on Germany, repudiated the Morgenthau-plan influenced policies. The United States administration, under President Harry Truman, realized that economic recovery in Europe could not go forward without the reconstruction of the German industrial base. The Marshall Plan (officially the European Recovery Program) was the primary plan of the United States for rebuilding and creating a stronger foundation for the Allied countries of Europe, and repelling communism after World War II. The initiative was named for Secretary of State George Marshall. The reconstruction plan was developed at a meeting of the participating European states on July 12, 1947. The Marshall Plan offered the same aid to the Soviet Union and its allies, if they would make political reforms and accept certain outside controls. However the Soviet Union rejected this proposal with Vyacheslav Molotov describing the plan as "dollar imperialism."

The plan was in operation for four years beginning in July 1947. During that period some $13-billion in economic and technical assistance were given to help the recovery of the European countries that had joined in the Organization for European Economic Co-operation. The $13-billion compares to the U.S. gross domestic product of $41-billion in 1949. By the time the plan had come to completion, the economy of every participant state, with the exception of Germany, had grown well past pre-war levels. Over the next two decades, many regions of Western Europe would enjoy unprecedented growth and prosperity. The Marshall Plan has also long been seen as one of the first elements of European integration, as it erased tariff trade barriers and set up institutions to coordinate the economy on a continental level. An intended consequence was the systematic adoption of American managerial techniques. A currency reform, which had been prohibited under the previous occupation directive JCS 1067, introduced the Deutsche Mark and halted rampant inflation.

Berlin blockade

In March 1948, the United States, Britain, and France agreed to unite the Western zones and to establish a West German republic. The Soviet Union responded by leaving the Allied Control Council and prepared to create an East German state. The division of Germany was made clear with the currency reform of June 20, 1948, which was limited to the western zones. Three days later a separate currency reform was introduced in the Soviet zone. The introduction of the western Deutsche Mark to the western sectors of Berlin against the will of the Soviet supreme commander, led the Soviet Union to introduce the Berlin Blockade in an attempt to gain control of the whole of Berlin. The Western Allies decided to supply Berlin via an "air bridge," which lasted 11 months, until the Soviet Union lifted the blockade on May 12, 1949.

Federal government formed

In April 1949, the French began to merge their zone into Bizonia, creating Trizonia. The Western Allies moved to establish a nucleus for a future German government by creating a central Economic Council for their zones. The program later provided for a West German constituent assembly. On May 23 of that year, the Grundgesetz (Basic Law), the constitution of the Federal Republic of Germany, established a federal republic. The bicameral parliament consisted of the Bundesrat (federal council, or upper house), and Bundestag (National Assembly, or lower house). The president was the titular head of state, while the chancellor was the executive head of government. Suffrage was universal to those aged 18 and over. National elections were to be held every four years. Voting combined proportional representation with single-seat constituencies. A party had to win a minimum of five percent of the overall vote to gain representation. The judiciary was independent. Legal system was based on civil law system with indigenous concepts. A Supreme Federal Constitutional Court reviewed legislative acts. The American, British, and French governments reserved ultimate authority over foreign relations, foreign trade, the level of industrial production, and military security. The nation was divided into ten states; Baden-Wurttemberg, Bayern, Bremen, Hamburg, Hessen, Niedersachsen, Nordrhein-Westfalen, Rheinland-Pfalz, Saarland, and Schleswig-Holstein.

The Adenauer era

Following elections in August, the first federal government was formed on September 20, 1949, by Konrad Adenauer (1876-1967), a coalition of the Christian Democrats with the Free Democrats. Adenauer, a veteran Roman Catholic politician from the Rhineland, was elected the country's first chancellor by a narrow margin, and despite his advanced age of 73, he retained the chancellorship for 14 years. Theodor Heuss of the Free Democratic Party was elected as West Germany's first president. Economics minister Ludwig Erhard launched a phenomenally successful social market economy, leaving the means of production in private hands and allowing the market to set price and wage levels. The profit motive was to power the economy. The government would regulate to prevent the formation of monopolies, and would set up a welfare state as a safety net. The initial problem Adenauer had was to resettle 4.5 million Germans from the territory east of the Oder-Neisse line, 3.4 million ethnic Germans from Czechoslovakia, prewar Poland, and other eastern European countries, and 1.5 million from East Germany. But because many of the refugees were skilled, enterprising, and adaptable, they contributed to West Germany's economic recovery.

Economic miracle

West Germany soon benefited from the currency reform of 1948 and the Allied Marshall Plan. Industrial production increased by 35 percent. Agricultural production substantially surpassed pre-war levels. The poverty and starvation of the immediate postwar years disappeared, and Western Europe and especially West Germany embarked upon an unprecedented two decades of growth that saw standards of living increase dramatically.

West Germany became famous for its Wirtschaftswunder, or ‚Äúeconomic miracle.‚ÄĚ The West German Wirtschaftswunder (English: "economic miracle") coined by The Times of London in 1950), was partly due to the economic aid provided by the United States and the Marshall Plan, but mainly due to the currency reform of 1948 which replaced the Reichsmark with the Deutsche Mark as legal tender, halting rampant inflation. Great Britain and France both received higher economic assistance from the Marshall Plan than Germany and neither showed signs of an economic miracle. In fact, the amount of monetary aid (which was in the form of loans) received by Germany through the Marshall Plan was far overshadowed by the amount the Germans had to pay back as war reparations and by the charges the Allies made on the Germans for the ongoing cost of occupation (about $2.4-billion per year). In 1953 it was decided that Germany was to repay $1.1-billion of the aid it had received. The last repayment was made in June 1971.

The Korean War (1950‚Äď1953) led to a worldwide increased demand for goods, and the resulting shortages helped overcome lingering resistance to the purchase of German products. Germany's large pool of skilled and cheap labor helped to more than double the value of its exports during the war. Hard work and long hours at full capacity among the population and in the late 1950s and 1960s extra labor supplied by thousands of Gastarbeiter ("guest workers") provided a vital base for the economic upturn.

West Germany re-arms

The outbreak of the Korean War in June 1950 led to U.S. calls for the rearmament of West Germany in order to help defend Western Europe from the perceived Soviet threat. Germany's partners in the Coal and Steel Community proposed to establish a European Defence Community (EDC), with an integrated army, navy and air force, composed of the armed forces of its member states. The West German military would be subject to complete EDC control. Though the EDC treaty was signed in May 1952, it never entered into force. France's Gaullists rejected it as a threat to national sovereignty, and the French National Assembly refused to ratify it. In response, the Brussels Treaty was modified to include West Germany, and to form the Western European Union. West Germany was to be permitted to re-arm, an idea which was rejected by many Germans, and have full sovereign control of its military called Bundeswehr, although the union would regulate the size of the armed forces. The German constitution prohibited any military action except in case of an external attack against Germany or its allies, and Germans could reject military service on grounds of conscience, and serve for civil purposes instead.

Unification considered

In 1952, West Germany became part of the European Coal and Steel Community, which would later evolve into the European Union. In that year the Stalin Note proposed German unification and superpower disengagement from Central Europe but the United States and its allies rejected the offer. Soviet leader Josef Stalin died in March 1953. Though powerful Soviet politician Lavrenty Beria briefly pursued the idea of German unification once more following Stalin's death, he was arrested and removed from office in a coup d'etat in mid-1953. His successor, Nikita Khrushchev, firmly rejected the idea of handing eastern Germany over to be annexed, marking the end of any serious consideration of the unification idea until the resignation of the East German government in 1989.

Sovereignty, NATO, and the Cold War

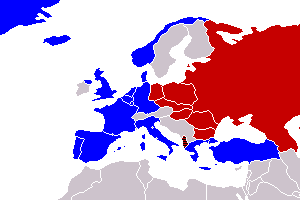

The Federal Republic of Germany was declared "fully sovereign" on May 5, 1955. The British, French and U.S. militaries remained in the country, just as the Soviet Army remained in East Germany. Four days after becoming "fully sovereign" in 1955, West Germany joined NATO, established in 1949 for the defense of Europe. West Germany became a focus of the Cold War, with its juxtaposition to East Germany, a member of the subsequently founded Warsaw Pact. The U.S. retained an especially strong presence in West Germany, acting as a deterrent in case of a Soviet invasion. The former capital, Berlin, had also been divided into four sectors, the Western Allies joining their sectors to form West Berlin, while the Soviets held East Berlin.

Berlin wall erected

East German President Wilhelm Pieck died in 1960, and Socialist Unity Party head Walter Ulbricht became head of a newly created Council of State, entrenching a totalitarian communist dictatorship. Due to the lure of higher salaries in the West and political oppression in the East, many skilled workers (such as doctors) crossed into the West, causing a 'brain drain' in the East. By 1961, three million East Germans had fled since the war. However, on the night of August 13, 1961, East German troops sealed the border between West and East Berlin and began building the Berlin Wall, enclosing West Berlin, first with barbed wire and later by construction of a concrete wall through the middle and around the city. East Germans could no longer go through the heavily guarded crossing points without permission, which was rarely granted. Those who tried to escape by climbing over the wall risked being shot by East German guards under orders to kill.

Stable political life

Political life in West Germany was remarkably stable and orderly. The Adenauer era (1949-1963) was followed by a brief period under Ludwig Erhard (1963-1966) who, in turn, was replaced by Kurt Georg Kiesinger (1966-1969). All governments between 1949 and 1966 were formed by the united caucus of the Christian-Democratic Union (CDU) and Christian Social Union (CSU), either alone or in coalition with the smaller Free Democratic Party (FDP).

Kiesinger's 1966‚Äď1969 "Grand Coalition" was between West Germany's two largest parties, the CDU/CSU and the Social Democratic Party (SPD). This was important for the introduction of new emergency acts‚ÄĒthe Grand Coalition gave the ruling parties the two-thirds majority of votes required to see them in. These controversial acts allowed basic constitutional rights such as freedom of movement to be limited in case of a state of emergency.

During the time leading up to the passing of the laws, there was fierce opposition to them, above all by the FDP, the rising German student movement, a group calling itself Notstand der Demokratie ("Democracy in a State of Emergency") and the labor unions. Demonstrations and protests grew in number, and in 1967 the student Benno Ohnesorg was shot in the head and killed by the police. The press, especially the tabloid Bild-Zeitung newspaper, launched a massive campaign against the protesters and in 1968, apparently as a result, there was an attempted assassination of one of the top members of the German socialist students' union, Rudi Dutschke.

1960s protest

In the 1960s a desire to confront the Nazi past came into being. Successfully, mass protests clamored for a new Germany. Environmentalism and anti-nationalism became fundamental values of West Germany. Rudi Dutschke recovered sufficiently to help establish the Green Party of Germany by convincing former student protesters to join the Green movement. As a result in 1979 the Greens were able to reach the five percent threshold required to obtain parliamentary seats in the Bremen provincial election. Dutschke died in 1979 due to the epilepsy resulting from the attack. Another result of the unrest in the 1960s was the founding of the Red Army Faction (RAF) which was active from 1968, carrying out a succession of terrorist attacks in West Germany during the 1970s. Even in the 1990s attacks were still being committed under the name "RAF." The last action took place in 1993 and the group announced it was giving up its activities in 1998.

Brandt and Ostpolitik

During the Cold War period, the prevailing legal opinion was that the Federal Republic was not a new West German state but a re-organized German Reich. Before the 1970s, the official position of West Germany concerning East Germany was that, according to the Hallstein Doctrine, the West German government was the only democratically elected and therefore legitimate representative of the German people, and any country (with the exception of the USSR) that recognized the authorities of the German Democratic Republic would not have diplomatic relations with West Germany. Article 23 of the West German Constitution provided the possibility for other parts of Germany to join the Federal Republic, and Article 146 provided the possibility for unification of all parts of Germany under a new constitution.

In the 1969 election, the SPD‚ÄĒheaded by Willy Brandt‚ÄĒgained enough votes to form a coalition government with the FDP. Brandt announced that West Germany would remain firmly rooted in the Atlantic alliance but would intensify efforts to improve relations with Eastern Europe and East Germany. West Germany commenced this Ostpolitik, initially under fierce opposition from the conservatives. The Treaty of Moscow (August 1970), the Treaty of Warsaw (December 1970), the Four Power Agreement on Berlin (September 1971), the Transit Agreement (May 1972), and the Basic Treaty (December 1972) helped to normalize relations between East and West Germany and led to both "Germanys" joining the United Nations, in September 1973. The two German states exchanged permanent representatives in 1974, and, in 1987, East German head of state Erich Honecker paid an official visit to West Germany.

Chancellor Brandt remained head of government until May 1974, when he resigned after a senior member of his staff was uncovered as a spy for the East German intelligence service, the Stasi. Finance Minister Helmut Schmidt (SPD) then formed a government and received the unanimous support of coalition members. He served as Chancellor from 1974 to 1982. Hans-Dietrich Genscher, a leading FDP official, became Vice Chancellor and Foreign Minister. Schmidt, a strong supporter of the European Community (EC) and the Atlantic alliance, emphasized his commitment to "the political unification of Europe in partnership with the USA."

Fourth largest GDP

In 1976, West Germany became one of the founding nations of the Group of Six (G6). In 1973, West Germany which was home to roughly 1.26 percent of the world's population, featured the world's fourth largest GDP of 944 billion (5.9 percent of the world total). In 1987, the FRG held a 7.4 percent share of total world production.

The Kohl era

In October 1982, the SPD-FDP coalition fell apart when the FDP joined forces with the CDU/CSU to elect CDU Chairman Helmut Kohl as Chancellor in a Constructive Vote of No Confidence. Following national elections in March 1983, Kohl emerged in firm control of both the government and the CDU. The CDU/CSU fell just short of an absolute majority, due to the entry into the Bundestag of the Greens, who received 5.6 percent of the vote. In January 1987, the Kohl-Genscher government was returned to office, but the FDP and the Greens gained at the expense of the larger parties.

In the 1987 election, the last held in West Germany before unification, the Christian Democratic Union-Christian Social Union took 44.3 percent of the vote, the Social Democratic Party took 37 percent, Free Democratic Party 9.1 percent, the Greens 8.3 percent, while others took the remaining 1.3 percent. There were about 40,000 communist members and supporters.

The economy in 1989

By 1989, the Federal Republic of Germany was a major economic power and one of the world's leading exporters. The country had a modern industrial economy, with a highly urbanized and skilled population. The republic was poor in natural resources, coal being the most important mineral found in the country. Having a highly skilled labor force but lacking a resource base, the republic's competitive advantage lay in the technologically advanced production stages. Thus manufacturing and services dominated economic activity, and raw materials and semimanufactures constituted a large proportion of imports. In 1987 manufacturing accounted for 35 percent of GNP, with other sectors contributing lesser amounts. West Germany's budget for its army, navy, and air force was $35.5-billion in 1988, or 22 percent of central government budget. Per capita GNP was $18,370, the unemployment rate was 8.7 percent in 1987, and the inflation rate (consumer prices) was 1.2 percent in 1988.

Reunification

After the democratic revolution of 1989 in Eastern Germany, and the fall of the Berlin Wall on November 9, 1989, the first freely elected East German parliament decided in June 1990 to join the Federal Republic under Article 23 of the (West-)German Basic Law. This made a quick unification possible. The two German states entered into a currency and customs union in July 1990. In July/August 1990 the East German parliament enacted a law for the establishment of federal states on the territory of the German Democratic Republic. This East German constitutional law converted the former centralized socialist structure of East Germany into a federal structure equal to that of Western Germany.

On October 3, 1990, the German Democratic Republic dissolved and the reestablished 5 East German states (as well East and West Berlin became unified) joined the Federal Republic of Germany bringing an end to the East-West divide. From a West German point of view Berlin already was a member state of the Federal Republic, therefore it was regarded as an old state. The official German reunification ceremony on October 3, 1990, was held at the Reichstag building, including Chancellor Helmut Kohl, President Richard von Weizsäcker, former Chancellor Willy Brandt and many others. One day later, the parliament of the united Germany would assemble in an act of symbolism in the Reichstag building. The four occupying powers officially withdrew from Germany on March 15, 1991. After a fierce debate, considered by many as one of the most memorable sessions of parliament, the Bundestag concluded on June 20, 1991, with a quite slim majority that both government and parliament should return to Berlin.

- Demographics at unification

West Germany's population was 60,977,195 in 1989, with a life expectancy at birth of 72 years for males, and 79 years for females. Most were of German ethnicity, with a small Danish minority. Regarding religion, 45 percent were Roman Catholic, 44 percent Protestant, and 11 percent "other." The language spoken was German, and 99 percent of the population aged 15 and over could read and write.

- Culture

During the 40 years of separation it was inevitable that some divergence would occur in the cultural life of the two parts of the severed nation. Both West Germany and East Germany followed along traditional paths of the common German culture, but West Germany, being obviously more susceptible to influences from western Europe and North America, became more cosmopolitan. Conversely, East Germany, while remaining surprisingly conservative in its adherence to some aspects of the received tradition, was powerfully molded by the dictates of a socialist ideology of predominantly Soviet inspiration. Guidance in the required direction was provided by exhortation through a range of associations and by some degree of censorship; the state, as virtually the sole market for artistic products, inevitably had the last word in East Germany.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Balfour, Michael Leonard Graham. 1982. West Germany: A contemporary history. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0312862970

- Fulbrook, Mary. 1990. A concise history of Germany. Cambridge concise histories. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521368360

- Kitchen, Martin. 1996. The Cambridge illustrated history of Germany. Cambridge illustrated history. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521453410

- Schissler, Hanna. 2001. The miracle years a cultural history of West Germany, 1949-1968. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691058207

- Smith, Jean Edward. 1969. Germany beyond the wall; people, politics … and prosperity. Boston: Little, Brown.

- Várdy, Steven Béla, and T. Hunt Tooley (eds.). 2003. Ethnic cleansing in twentieth-century Europe. Boulder: Social Science Monographs. ISBN 0880339950

External links

All links retrieved May 4, 2023.

- Germany, Federal Republic of - 1989 Theodora.com

- German Economic 'Miracle' by David R. Henderson. The Library of Economics and Liberty.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.