| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

East Germany (in German Ostdeutschland) was the common English name for the former German Democratic Republic (in German, Deutsche Demokratische Republik, or GDR), a communist state which existed from its founding on October 7, 1949, to October 3, 1990.

With an area of 40,919 square miles (105,980 square kilometers), or slightly smaller than the U.S. state of Tennessee, East Germany was bordered on the east by Czechoslovakia and Poland, and on the west by the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany).

The German Democratic Republic was established in the Soviet occupation zone of Germany on October 7, 1949, following the creation, in May 1949, of the Federal Republic of Germany. East Berlin became the capital of East Germany, which consisted of the current German states of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Brandenburg, Saxony-Anhalt, Thuringia, Saxony, and the eastern part of Berlin.

In 1955, the Republic was declared by the Soviet Union to be fully sovereign. However, Soviet troops remained, based on the four-power Potsdam Agreement. As NATO troops remained in West Berlin and West Germany, the GDR and Berlin, in particular, became focal points of Cold War tensions. East Germany was a member of the Warsaw Pact and a close ally of the Soviet Union.

Following the initial opening of sections of the Berlin Wall on November 9, 1989, new elections held on March 18, 1990, meant the governing SED lost its majority in the Volkskammer (the East German parliament). On August 23, the Volkskammer decided that the territory of the Republic would accede to the ambit claim of the Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany on October 3, 1990. As a result of the unification on that date, the German Democratic Republic officially ceased to exist.

History

After the German military leaders unconditionally surrendered to Allied forces on May 8, 1945, Germany was devastated, with about 25 percent of the country's housing damaged beyond use. Factories and transport ceased to function, soaring inflation undermined the currency, food shortages meant city dwellers starved, while millions of homeless German refugees flooded west from the former eastern provinces. Sovereignty was in the hands of the victorious allied nations. Everything had to be rebuilt.

Occupation zones established

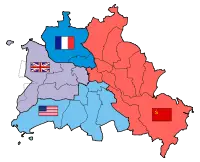

At the Yalta Conference, held in February 1945, the United States, United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union agreed on the division of Germany into occupation zones. The Potsdam Conference of July/August 1945, officially recognized the four zonesâFrench in the southwest, British in the northwest, United States in the south, and Soviet in the eastâand confirmed jurisdiction of the Soviet Military Administration in Germany (SMAD) from the Oder and Neisse rivers to the demarcation line. The Soviet occupation zone included the former states of Brandenburg, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, and Thuringia. The city of Berlin was placed under the control of the four powers.

The German territory east of the Oder-Neisse line, equal in size to the Soviet occupation zone, was handed over to Poland and the Soviet Union, with the larger share going to the Poles as compensation for territory they lost to the Soviet Union. About 9.5 million Germans still remaining in these areas were over a period of several years expelled and replaced by Polish and Soviet settlers. This amounted to a de facto annexation of 25 percent of Germany's territory as of 1937. Estimates of casualties from the expulsion range from hundreds of thousands to several million. In the GDR, the euphemism "resettlement" was officially used to describe this event.

The intended governing body of Germany was called the Allied Control Council. The commanders-in-chief exercised supreme authority in their respective zones and acted in concert on questions affecting the whole country. Berlin, which lay in the Soviet (eastern) sector, was also divided into four sectorsâwith the Western sectors later becoming West Berlin and the Soviet sector becoming East Berlin, capital of East Germany.

Widespread rape

Norman Naimark writes in The Russians in Germany: A History of the Soviet Zone of Occupation, 1945-1949. that although the exact number of women and girls who were raped by members of the Red Army in the months preceding and years following the capitulation will never be known, their numbers are likely in the hundreds of thousands, quite possibly as high as two million victims. Many of these victims were raped repeatedly. Naimark states that not only did each victim have to carry the trauma with her for the rest of her days, it inflicted a massive collective trauma on the East German nation. Naimark concludes, "The social psychology of women and men in the soviet zone of occupation was marked by the crime of rape from the first days of occupation, through the founding of the GDR in the fall of 1949, untilâone could argueâthe present."

Industries confiscated

Each occupation power assumed rule in its zone by June 1945. The powers originally pursued a common German policy, focused on denazification and demilitarization in preparation for the restoration of a democratic German nation-state. Over time, however, the western zones and the Soviet zone drifted apart economically, not least because of the Soviets' much greater use of disassembly of German industry under its control as a form of reparations. Military industries and those owned by the state, by Nazi activists, and by war criminals were confiscated. These industries amounted to approximately 60 percent of total industrial production in the Soviet zone. Most heavy industry (constituting 20 percent of total production) was claimed by the Soviet Union as reparations, and Soviet joint stock companies (German: Sowjetische Aktiengesellschaften, or SAG) were formed. The remaining confiscated industrial property was nationalized, leaving 40 percent of total industrial production to private enterprise.

A key item in the occupiers' agenda was denazification; toward this end, the swastika and other outward symbols of the Nazi regime were banned, and a Provisional Civil Ensign was established as a temporary German flag. A strict non-fraternization policy was adhered to by General Eisenhower and the War department, although this was lifted in stages.

Land expropriated

The agrarian reform expropriated all land belonging to former Nazis and war criminals and generally limited ownership to one square kilometer. Some 500 Junker estates were converted into collective people's farms, and more than 30,000 km² were distributed among 500,000 peasant farmers, agricultural laborers, and refugees. Also, state farms were set up, called Volkseigenes Gut (State Owned Property).

Berlin blockade

Growing economic differences combined with developing political tensions between the U.S. and the Soviet Union (which would eventually develop into the Cold War) and manifested in the refusal in 1947 of the SMAD to take part in America's Marshall Plan. In March 1948, the United States, Britain, and France met in London and agreed to unite the Western zones and to establish a West German republic. The Soviet Union responded by leaving the Allied Control Council and prepared to create an East German state. The division of Germany was made clear with the currency reform of June 20, 1948, which was limited to the western zones. Three days later, a separate currency reform was introduced in the Soviet zone. The introduction of the western Deutsche Mark to the western sectors of Berlin against the will of the Soviet supreme commander, led the Soviet Union to introduce the Berlin Blockade in an attempt to gain control of the whole of Berlin. The Western Allies decided to supply Berlin via an "air bridge," which lasted 11 months, until the Soviet Union lifted the blockade on May 12, 1949.

The rise of the Socialist Unity Party

Permission was granted for the formation of anti-fascist democratic political parties in the Soviet zone, with elections to new state legislatures scheduled for October 1946. A democratic-anti-fascist coalition, which included the KPD, the SPD, the new Christian Democratic Union (Christlich-Demokratische UnionâCDU), and the Liberal Democratic Party of Germany (Liberal Demokratische Partei DeutschlandsâLDPD), was formed in July 1945. The KPD (with 600,000 members, led by Wilhelm Pieck) and the SPD in East Germany (with 680,000 members, led by Otto Grotewohl), which was under strong pressure from the Communists, merged in April 1946, to form the Socialist Unity Party of Germany (Sozialistische Einheitspartei DeutschlandsâSED). In the October 1946 elections, the SED polled approximately 50 percent of the vote in each state in the Soviet zone. In Berlin, which was still undivided, the SPD had resisted the party merger and, running on its own, had polled 48.7 percent of the vote, decisively defeating the SED, which, with 19.8 percent, was third in the voting behind the SPD and the CDU.

When a West German government was likely to be established, an election for a People's Congress was held in the Soviet occupation zone in May 1949. Instead of choosing among candidates, voters were able to approve or reject "unity listsâ of candidates drawn from all parties, as well as representatives of organizations controlled by the communist-dominated SED. Two additional parties, a Democratic Farmers' Party and a National Democratic Party (the latter aimed at former Nazis) were added. By ensuring that communists predominated in these unity lists, the SED determined in advance the composition of the new People's Congress. About two-thirds of the voters approved the unity lists, while in subsequent elections, favorable margins in excess of 99 percent were announced.

The SED modeled itself as a Soviet-style party, with veteran German communist Walter Ulbricht (1893-1973) the first secretary of the SED. A Politburo, Secretariat, and Central Committee were formed. The SED committed itself ideologically to Marxism-Leninism and the international class struggle. Many former members of the SPD and some communist advocates of a social-democratic road to socialism were purged from the SED. The SED accorded political representation to mass organizations and, most significant, to the party-controlled Free German Trade Union Federation.

German Democratic Republic established

In November 1948, the German Economic Commission (Deutsche WirtschaftskomissionâDWK), including anti-fascist bloc representation, assumed administrative authority. Five weeks after declaration of the western Federal Republic of Germany, on October 7, 1949, a constitution ratified by the People's Congress went into effect in the Soviet zone, which became the German Democratic Republic (Deutsche Demokratische Republik), commonly known as East Germany, with its capital in the Soviet sector of Berlin.

The German Democratic Republic was created as a socialist republic in 1949 and began to institute a government based on that of the Soviet Union. The constitutional structure consisted of a directly elected unicameral legislature or People's Chamber (Volkskammer), an executive Council of Ministers, and a judiciary. Although constitutionally a parliamentary democracy, actual power lay with the SED and its boss, Walter Ulbricht, who was deputy premier in the government. As in the Soviet Union, the government was the agent of the communist-controlled Socialist Unity Party, which was ruled by a self-selecting Politburo. As the Potsdam Agreement had committed the Soviets to supporting a democratic form of government in Germany, other political parties were technically permitted, although in practice they had no political power and were not allowed to meaningfully question or oppose government policy. Along with other parties, the SED was part of the "National Front of Democratic Germany," ostensibly a united coalition of anti-fascist political parties.

Suffrage was universal to all citizens age 18 and over. National elections took place every five years, and were prepared by an electoral commission of the National Front. The ballot was supposed to be secret and voters were permitted to strike names off ballot. There were 2.195 million party members in 1986.

The Volkskammer also included representatives from the mass organizations like the Free German Youth (Freie Deutsche Jugend or FDJ), or the Free German Trade Union Federation. In an attempt to include women in the political life of East Germany, there was a Democratic Women's Federation of Germany, with seats in the Volkskammer.

Important non-parliamentary mass organisations in East German society included the German Gymnastics and Sports Association (Deutscher Turn- und Sportbund or DTSB), and People's Solidarity (Volkssolidarität, an organization for the elderly). Another society of note (and very popular during the late 1980s) was the Society for German-Soviet Friendship.

The legal system was based on civil law system modified by Communist legal theory. The court system paralleled administrative divisions. There was no judicial review of legislative acts. Easy Germany did not accept compulsory International Court of Justice jurisdiction.

A highly effective secret police force called the Stasi infiltrated and reported on most private activity in East Germany, limiting opportunity for non-sanctioned political organization. All formal organizations except for churches were directly controlled by the East German government. Churches were permitted to operate more or less free from government control, as long as they abstained from political activity.

In 1952, as part of the reforms designed to centralize power in the hands of the SED's Politbßro, the five Länder of East Germany were abolished, and East Germany was divided into 15 Bezirke (districts), each named after the largest city.

The People's Chamber named Wilhelm Pieck, a party leader, first president on October 11, 1949. The next day, former Social Democrat Otto Grotewohl was installed as premier at the head of a cabinet, nominally responsible to the chamber.

Centrally planned economy imposed

The Socialist Unity Party concentrated on building an economy in a territory lacking natural resources, that was less than one-half the size of the Federal Republic, and which had a population one-third as large. The industrial sector, employing 40 percent of the working population, was subjected to further nationalization, resulting in the formation of the People's Enterprises (German: Volkseigene BetriebâVEB). The First Five-Year Plan (1951â55) introduced centralized state planning, stressing high production quotas for heavy industry and increased labor productivity. The construction of basic industries was emphasized at the expense of the production of consumer goods. War reparations required that much productive capacity be diverted to Soviet needs.

Exodus increases

The standard of living lagged far behind that of West Germany. Food rationing continued long after it had ended in West Germany. Thousands of farmers fled to West Germany each year rather than merge their land into the collective farms. The pressures of the plan, plus relentless ideological indoctrination, repression of dissent, and harassment of churches by a militantly atheistic regime, caused an exodus of East German citizens to West Germany. In 1951, monthly emigration figures fluctuated between 11,500 and 17,000. In 1952, East Germany sealed its borders, but East Germans continued to leave through Berlin, where free movement still prevailed. By 1953 an average of 37,000 men, women and children were leaving each month.

There were also other indications of opposition, even from within the government itself. In the fall of 1950, several prominent members of the SED were expelled and arrested as "saboteurs" or "for lacking trust in the Soviet Union." Among them were the Deputy Minister of Justice, Helmut Brandt; the Vice-President of the Volkskammer, Joseph Rambo; Bruno Foldhammer, deputy to Gerhard Eisler; and the editor, Lex Ende.

The regime enacted anti-family legislation. Under a law passed by the Volkskammer in 1950, the age at which Germany's youth may reject parental supervision was lowered from 21 to 18. At the end of 1954 the draft of a new family code was published which aimed at destroying all parental influence.

Unification considered

The 1952, the Stalin Note proposed German unification and superpower disengagement from Central Europe but the United States and its allies rejected the offer. Soviet leader Josef Stalin died in March 1953. Though powerful Soviet politician Lavrenty Beria briefly pursued the idea of German unification once more following Stalin's death, he was arrested and removed from office in a coup d'etat in mid-1953. His successor, Nikita Khrushchev, firmly rejected the idea of handing eastern Germany over to be annexed, marking the end of any serious consideration of the unification idea until the resignation of the East German government in 1989.

Uprising and crackdown

On June 16, 1953, following a production quota increase of 10 percent for workers building East Berlin's new boulevard the Stalinallee, (today's Karl-Marx-Allee), demonstrations by disgruntled workers broke out in East Berlin, the first popular uprising in the postwar Soviet bloc. The next day the protests spread across East Germany with more than a million on strike and demonstrations in 700 communities. Fearing revolution, the government requested the aid of Soviet occupation troops and on the morning of the 18th tanks and soldiers were dispatched who dealt harshly with protesters. Soviet troops killed 21 people, wounded hundreds of others, and 1300 were jailed. The Socialist Unity Party announced the New Course which aimed at improvement in the standard of living, stressed a shift in investment toward light industry and trade and a greater availability of consumer goods. The party relaxed pressure on farmers to enter collective farms. Agricultural yields improved, and the last food rationing ended in 1958.

In 1954, the Soviet Union granted sovereignty to the German Democratic Republic, and the Soviet Control Commission in Berlin was disbanded. By this time, reparations payments had been completed. In 1955, East Germany became a charter member of the Warsaw Pact, the Soviet bloc's military alliance.

Berlin wall erected

President Pieck died in 1960, and Ulbricht became head of a newly created Council of State, entrenching a totalitarian communist dictatorship. Due to the lure of higher salaries in the West and political oppression in the East, many skilled workers (such as doctors) crossed into the West, causing a 'brain drain' in the East. By 1961, three million East Germans had fled since the war. However, on the night of August 13, 1961, East German troops sealed the border between West and East Berlin and started to build the Berlin Wall, literally and physically enclosing West Berlin, first with barbed wire and later by construction of a concrete wall through the middle and around the city. East Germans could no longer go through the heavily guarded crossing points without permission, which was rarely granted. Those who tried to escape by climbing over the wall risked being shot by East German guards under orders to kill. With a captive population, the East German economy stabilized to become the most prosperous in the Soviet bloc but behind that of West Germany. A highly effective security force called the Stasi monitored the lives of East German citizens to suppress dissenters through its network of informants and agents.

New economic system

The annual industrial growth rate declined steadily after 1959. In 1963, Ulbricht adapted the theories reforms of Soviet economist Evsei Liberman, and introduced the New Economic System (NES), an economic reform program providing for some decentralization in decision making. Under the NES, The central planning authorities set overall production goals, but each VVB determined its own internal financing, utilization of technology, and allocation of manpower and resources. The NES brought forth a new elite in politics as well as in management of the economy, and in 1963 Ulbricht announced a new policy regarding admission to the leading ranks of the SED. Ulbricht opened the Politburo and the Central Committee to younger members who had more education than their predecessors and who had acquired managerial and technical skills. From 1964 until 1967, real wages increased, and the supply of consumer goods, including luxury items, improved.

The Trabant

The Trabant is an automobile formerly produced by East German auto maker VEB Sachsenring Automobilwerke Zwickau in Zwickau, Saxony. It was the most common vehicle in East Germany, and was exported to other countries in, but also outside, the communist bloc. The main selling points were that it had room for four adults and luggage, and was compact, fast, light, and durable. Despite its poor performance and smoky two-stroke engine, the car has come to be regarded with affection as a symbol of the more positive sides of East Germany. It was in production without any significant change for nearly 30 years. Since it could take years for a Trabant to be delivered from the time it was ordered, people who finally got one were very careful with it and usually became skillful in maintaining and repairing it. The lifespan of an average Trabant was 28 years. Used Trabants would often fetch a higher price than new ones, as the former were available immediately, while the latter had the aforementioned waiting period of several years.

Honecker and East-West rapprochement

The election of 1969 in West Germany brought in a new era with the Social Democrat-FDP social-liberal coalition with Willy Brandt as chancellor. While confirming West Germany's commitment to the Western alliance, the new government began a new âeastern policy,â or Ostpolitik. Where as under the Hallstein Doctrine, West Germany had refused to recognize the existence of the East German government, the Brandt administration opened direct negotiations with East Germany, in 1970, to normalize relations.

Meanwhile, in 1971, Erich Honecker (1912-1994) replaced Walter Ulbricht as head of state. Honecker combined loyalty to the Soviet Union with flexibility toward dĂŠtente. At the Eighth Party Congress in June 1971, he presented the political program of the new regime. In his reformulation of East German foreign policy, Honecker renounced the objective of a unified Germany and adopted the "defensive" position of ideological Abgrenzung (demarcation or separation). Under this program, the country defined itself as a distinct "socialist state" and emphasized its allegiance to the Soviet Union. Abgrenzung, by defending East German sovereignty, in turn contributed to the success of dĂŠtente negotiations that led to the Four Power Agreement on Berlin (Berlin Agreement) in 1971, and the Basic Treaty with West Germany in December 1972.

The Berlin Agreement (effective June 1972), signed by the United States, Britain, France, and the Soviet Union, protected trade and travel relations between West Berlin and West Germany and aimed at improving communications between East Berlin and West Berlin. The Basic Treaty (effective June 1973) politically recognized two German states, and the two countries pledged to respect one another's sovereignty. Under the terms of the treaty, diplomatic missions were to be exchanged and commercial, tourist, cultural, and communications relations established. In September 1973, both countries joined the United Nations, and thus, East Germany received its long-sought international recognition.

East-West economic gap widens

East Germany gained the international acceptance that it had long sought, and trade between the two German states increased, earning West German currency for East Germany, as well as income from fees paid by West Germany for use of the highways through East Germany to Berlin, and from ransoms paid for the release of political prisoners. However, the material gap between the two parts of Germany widened. As East Germany focussed on industrial production for export, the country's roads, railways, and buildings deteriorated, while a housing shortage persisted. Waiting periods of years were still required for the purchase of major consumer items such as automobiles, which continued to be crudely manufactured according to standards of the early postwar period, while those of West Germany ranked high in the world for quality and advanced design.

Dissidents

In spite of dĂŠtente, the Honecker regime remained committed to Soviet-style socialism and continued a strict policy toward dissidents. Nevertheless, a critical Marxist intelligentsia within the SED renewed the plea for democratic reform. Among them was the poet-singer Wolf Biermann, who with Robert Havemann had led a circle of artists and writers advocating democratization; he was expelled from East Germany in November 1976, for dissident activities. Following Biermann's expulsion, the SED leadership disciplined more than 100 dissident intellectuals.

Despite the government's actions, East German writers began to publish political statements in the West German press and periodical literature. The most prominent example was Rudolf Bahro's Die Alternative, which was published in West Germany in August 1977. The publication led to the author's arrest, imprisonment, and deportation to West Germany. In late 1977, a manifesto of the "League of Democratic Communists of Germany" appeared in the West German magazine Der Spiegel. The league, consisting ostensibly of anonymous middle- to high-ranking SED functionaries, demanded democratic reform in preparation for reunification.

Even after an exodus of artists in protest against Biermann's expulsion, the SED continued its repressive policy against dissidents. The state subjected literature, one of the few vehicles of opposition and nonconformism in East Germany, to ideological attacks and censorship. This policy led to an exodus of prominent writers, which lasted until 1981. The Lutheran Church also became openly critical of SED policies. Although in 1980-81, the SED intensified its censorship of church publications in response to the Polish Solidarity movement, it maintained, for the most part, a flexible attitude toward the church. The consecration of a church building in May 1981, in EisenhĂźttenstadt, which according to the SED leadership was not permitted to build a church owing to its status as a "socialist city," demonstrated this flexibility.

Chancellors visit

West Germany's Chancellor, Helmut Schmidt, paid an official visit to East Germany in December 1981, after which East Germany made it easier for its citizens to visit West Germany. By 1986, nearly 250,000 East Germans were visiting West Germany each year, although only one family member at a time was permitted to go. The East German government also began granting permission for some to emigrate. In return, West Germany guaranteed several large Western bank loans to East Germany. In 1987, Honecker was received in Bonn by Chancellor Helmut Kohl.

The economy in 1985

In the German Democratic Republic, the state established production targets and prices and allocated resources, codifying these decisions in a comprehensive plan or set of plans. The means of production were almost entirely state-owned. In 1985, for example, state-owned enterprises or collectives earned 96.7 percent of total net national income. To secure constant prices for inhabitants, the state bore 80 percent of costs of basic supplies, from bread to housing.

Agricultural land was 95 percent collectivized, and financial institutions, transportation, and industrial and foreign trade enterprises are state owned. The republic was the most industrialized country in Eastern Europe, with over half of its GNP generated by the industrial sector. It also enjoyed the highest standard of living among Communist countries, with a per capita GNP of $12,500 in 1988. The inflation rate (consumer prices) was 0.9 percent in 1987. There were no figures for unemployment.

Trade was characterized by exports of manufactured goods and imports of basic raw materials (lignite is the only important natural resource found in the GDR). About 65 percent of foreign trade was with the USSR and other CEMA countries. The GDR's most important trade partner in the West was the Federal Republic of Germany, which provided the GDR with interest-free credit under a special trade arrangement. During the period 1982-88, overall economic growth slowed to 1.5 percent from a rate of 2.0 percent during 1976-80. The GDR faced numerous economic problems that included low hard currency earnings, stagnating living standards, shortages of energy and labor, and an inadequate level of capital investment.

The private sector of the economy was small but not entirely insignificant. In 1985, about 2.8 percent of the net national product came from private enterprises. The private sector included private farmers and gardeners; independent craftsmen, wholesalers, and retailers; and individuals employed in so-called free-lance activities (artist, writers, and others). Although self-employed, such individuals were strictly regulated; in some cases, the tax rate exceeded 90 percent. In 1985, for the first time in many years, the number of individuals working in the private sector increased slightly. According to East German statistics, in 1985, there were about 176,800 private entrepreneurs, an increase of about 500 over 1984. Certain private sector activities were quite important to the system because those craftsmen provided rare, specially made spare parts.

More difficult to assess, because of its covert and informal nature, was the significance of that part of the private sector called is the "second economy." As used here, the term includes all economic arrangements or activities that, owing to their informality or their illegality, took place beyond state control or surveillance. The subject has received considerable attention from Western economists, most of whom are convinced that it is important in CPEs. In the mid-1980s, however, evidence was difficult to obtain and tended to be anecdotal in nature.

These irregularities did not appear to constitute a major economic problem. However, the East German press occasionally reported prosecutions of egregious cases of illegal "second economy" activity, involving what are called "crimes against socialist property" and other activities that are in "conflict and contradiction with the interests and demands of society," as one report described the situation.

Another common activity that was troublesome if not disruptive was the practice of offering a sum of money beyond the selling price to individuals selling desirable goods, or giving something special as partial payment for products in short supply, the so called BĂźckware (duck goods; sold from "below the counter"). Such ventures may have been no more than offering someone Trinkgeld (a tip), but they may have also involved Schmiergeld (money used to "grease" a transaction) or Beziehungen (special relationships). Opinions in East Germany varied as to how significant these practices were. But given the abundance of money in circulation and frequent shortages in luxury items and durable consumer goods, most people were perhaps occasionally tempted to provide a "sweetener," particularly for such things as automobile parts or furniture.

Debt crisis

Although in the end political circumstances led to the collapse of the SED regime, the GDR's growing international (hard currency) debts were leading towards an international debt crisis within a year or two. Debts continued to grow in the course of the 1980s, to over DM40 billion owed to western institutions, a sum not astronomical in absolute terms (the GDR's GDP was perhaps DM250bn) but much larger in relation to the GDR's capacity to export sufficient goods to the west to provide the hard currency to service these debts. Much of the debt originated from attempts by the GDR to export its way out of its international debt problems, which required imports of components, technologies and raw materials; as well as attempts to maintain living standards through imports of consumer goods. The GDR was internationally competitive in some sectors such as mechanical engineering and printing technology. However the attempt to achieve a competitive edge in microchips against the research and development resources of the entire western worldâin a state of just 16 million peopleâwas perhaps always doomed to failure, but swallowed increasing amounts of internal resources and hard currency. A significant factor was also the elimination of a ready source of hard currency through re-export of Soviet oil, which until 1981, was provided below world market prices; the resulting loss of hard currency income produced a noticeable dip in the otherwise steady improvement of living standards.

Honecker resigns

In September 1989, Hungary removed its border restrictions and unsealed its border and more than 13,000 people left East Germany by crossing the "green" border via Czechoslovakia into Hungary and then on to Austria and West Germany. Many others demonstrated against the ruling party, especially in the city of Leipzig. Kurt Masur, the conductor of the Leipzig Gewandhaus orchestra led local negotiations with the government, and held town meetings in the concert hall. The demonstrations eventually led Erich Honecker to resign and in October he was replaced by Egon Krenz.

Re-unification

On November 9, 1989, a few sections of the Berlin Wall were opened, resulting in thousands of East Germans crossing into West Berlin and West Germany for the first time. Soon, the governing party of East Germany resigned. Although there were some small attempts to create a permanent, democratic East Germany, these were soon overwhelmed by calls for unification with West Germany. After some negotiations (2+4 Talks, involving the two Germanies and the former Allied Powers United States, France, United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union), conditions for German unification were agreed upon. The East German territory was reorganized into five states. Thus, on October 3, 1990, the five East German states plus East Berlin joined the Federal Republic of Germany.

- Demographics at unification

East Germany's population was 16,586,490 in 1989, with a life expectancy at birth of 70 years for males, and 76 years for females. A total of 99.7 percent were of German ethnicity, while 0.3 percent were Slavic and other. About 47 percent of the population was nominally Protestant, seven percent Roman Catholic, and 46 percent unaffiliated or other. Fewer than five percent of Protestants and about 25 percent of Roman Catholics were active participants. The language spoken was German, and 99 percent of the population aged 15 and over could read and write.

Conclusion

To this day, there remain vast differences between the former East Germany and West Germany (for example, in lifestyle, wealth, political beliefs, and other matters) and thus, it is still common to speak of eastern and western Germany distinctly. The Eastern German economy has struggled since unification, and large subsidies are still transferred from west to east. During the 40 years of separation, it was inevitable that some divergence would occur in the cultural life of the two parts of the severed nation. Both West Germany and East Germany followed along traditional paths of the common German culture, but West Germany, being obviously more susceptible to influences from western Europe and North America, became more cosmopolitan. Conversely, East Germany, while remaining surprisingly conservative in its adherence to some aspects of the received tradition, was powerfully molded by the dictates of a socialist ideology of predominantly Soviet inspiration. Guidance in the required direction was provided by exhortation through a range of associations and by some degree of censorship; the state, as virtually the sole market for artistic products, inevitably had the last word in East Germany.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Childs, David, Thomas A. Baylis, and Marilyn Rueschemeyer. 1989. East Germany in Comparative Perspective. London: Routledge. ISBN 9780415004961.

- Fulbrook, Mary. 2005. The People's State East German Society from Hitler to Honecker. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300108842.

- Fulbrook, Mary. 1995. Anatomy of a Dictatorship Inside the GDR, 1949-1989. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198203124.

- Gray, William Glenn. 2003. Germany's Cold War: The Global Campaign to Isolate East Germany, 1949-1969. New Cold War history. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9780807862483.

- Grix, Jonathan. 2000. The Role of the Masses in the Collapse of the GDR. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Macmillan Press. ISBN 9780312235666.

- Jarausch, Konrad Hugo. 1999. Dictatorship as Experience Towards a Socio-Cultural History of the GDR. New York: Berghahn Books. ISBN 9781571811820.

- Port, Andrew Ian. 2000. Conflict and Stability in the German Democratic Republic a Study in Accommodation and Working-Class Fragmentation, 1945-1971. Thesis (Ph. D., Department of History)âHarvard University, 2000.

- Norman M. Naimark. The Russians in Germany: A History of the Soviet Zone of Occupation, 1945-1949. Harvard University Press, 1995. ISBN 0-674-78405-7.

External links

All links retrieved February 12, 2024.

- German Democratic Republic Theodora.com.

- DDR Museum.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- East_Germany history

- History_of_Germany_since_1945Â history

- History_of_the_German_Democratic_Republic history

- Politics_of_East_Germany history

- Economy_of_East_Germany history

- Trabant history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.