Eritrea

| ሃገረ ኤርትራ Hagere Ertra دولة إرتريا Dawlat Iritrīya State of Eritrea |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Anthem: Ertra, Ertra, Ertra Eritrea, Eritrea, Eritrea |

||||||

| Capital (and largest city) | Asmara 15°20′N 38°55′E | |||||

| Official languages | Tigrinya Arabic English [1] |

|||||

| Other languages | Tigre, Saho, Bilen, Afar, Kunama, Nara, Hedareb[2][1] | |||||

| Ethnic groups | ||||||

| Demonym | Eritrean | |||||

| Government | Provisional government | |||||

| - | President | Isaias Afewerki | ||||

| Independence | ||||||

| - | From Italy | November 1941 | ||||

| - | From United Kingdom under UN Mandate | 1951 | ||||

| - | from Ethiopia de facto | 24 May 1991 | ||||

| - | From Ethiopia de jure | 24 May 1993 | ||||

| Area | ||||||

| - | Total | 117,600 km² (100th) 45,405 sq mi |

||||

| - | Water (%) | 0.14% | ||||

| Population | ||||||

| - | 2017 estimate | 5,918,919[1] (112th) | ||||

| - | Density | 51.8/km² (154th) 134.2/sq mi |

||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2018 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $10.176 billion[3] | ||||

| - | Per capita | $1,466[3] | ||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2018 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $6.856 billion[3] | ||||

| - | Per capita | $988[3] | ||||

| Currency | Nakfa (ERN) |

|||||

| Time zone | EAT (UTC+3) | |||||

| - | Summer (DST) | not observed (UTC+3) | ||||

| Internet TLD | .er | |||||

| Calling code | +291 | |||||

Eritrea, officially State of Eritrea, is a country situated in northern East Africa. A former colony of Italy, it fought a thirty-year war with Ethiopia for its independence. A subsequent border conflict with Ethiopia from 1998-2000 still simmers. Eritrea's government has been accused of using the prolonged conflict as an excuse to crack down on all dissidents and restrict freedom of the press and religious freedom. No elections have been held since the current president took office following independence in 1991.

Remains of one of the oldest known hominids, dated to over one million years ago, were discovered in Eritrea in 1995. In 1999 scientists discovered some of the first examples of humans using tools to harvest marine resources at a site along the Red Sea coast.

The Eritrean economy is largely based on agriculture, which employs 80 percent of the population. Although the government claimed that it was committed to a market economy and privatization, it maintains complete control of the economy and has imposed an arbitrary and complex set of regulatory requirements that discourage investment from both foreign and domestic sources.

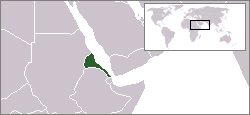

Geography

Eritrea is located in East Africa, more specifically the Horn of Africa, and is bordered on the northeast and east by the Red Sea. It is bordered by Sudan in the west, Ethiopia in the south, and Djibouti in the southeast. Its area is approximately that of the U.S. state of Pennsylvania, though half of that includes the territorial waters that surround the Dahlak Archipelago, a cluster of 209 islands in the Red Sea.

The country is virtually bisected by one of the world's longest mountain ranges, the Great Rift Valley, with fertile lands in the central highlands, a savanna to the west, and the descent to the barren coastal plain in the east. Off the sandy and arid coastline is situated the Dahlak Archipelago, a group of more than 100 small coral and reef-fringed islands, only a few of which have a permanent population.

The highlands are drier and cooler, and half of Eritrea's population lives here. The central highlands receive between 16 and 20 inches of rain (406 to 508 mm) annually and are drained by four rivers and numerous streams, which in some areas carve deep gorges. The soil is fertile.

The highest point of the country, Amba Soira, is located in the center of Eritrea, at 9,902 feet (3,018 m) above sea level. The lowest point is the Kobar Sink within the Denakil Plain, which reaches a maximum depth of 380 feet (116 m) below sea level, making it one of the lowest places on earth not covered by water. It is also the world's hottest place.

The Afar Triangle or Denakil Depression is the probable location of a triple junction where three tectonic plates are pulling away from one another: the Arabian Plate, and the two parts of the African Plate (the Nubian and the Somalian) splitting along the East African Rift Zone.

In 2006, Eritrea announced it would become the first country in the world to turn its entire coast into an environmentally protected zone. The 837-mile (1,347 km) coastline, along with another 1,209 miles (1,946 km) of coast around its more than 350 islands, have come under governmental protection.

The main cities of the country are the capital city of Asmara and the port town of Asseb in the southeast, as well as the towns of Massawa to the east, and Keren to the north.

History

The oldest written reference to the territory now known as Eritrea is the chronicled expedition launched to the fabled Punt by the Ancient Egyptians in the twenty-fifth century B.C.E. The geographical location of the missions to Punt is described as roughly corresponding to the southern west coast of the Red Sea.

The modern name Eritrea was first employed by Italian colonialists in the late nineteenth century. It is the Italian form of the Greek name Erythraîa, which derives from the Greek term for the Red Sea.

Pre-history

One of the oldest hominids, representing a link between Homo erectus and an archaic Homo sapiens, was found in Buya (in the Denakil Depression) in 1995. The cranium was dated to over one million years old.[4] In 1999 scientists discovered some of the first examples of humans using tools to harvest marine resources at a site along the Red Sea coast. The site contained obsidian tools dated to over 125,000 years old, from the Paleolithic era. Cave paintings in central and northern Eritrea attest to the early settlement of hunter-gatherers in this region.

Early history

The earliest evidence of agriculture, urban settlement, and trade in Eritrea was found in the region inhabited by people dating back to 3,500 B.C.E. Based on the archaeological evidence, there seems to have been a connection between those peoples and the civilizations of the Nile River Valley, namely Ancient Egypt and Nubia.[5]Ancient Egyptian sources also cite cities and trading posts along the southwestern Red Sea coast, roughly corresponding to modern-day Eritrea, calling this the land of Punt famed for its incense.

In the highlands, another site was found from the ninth century B.C.E. of a settlement that traded both with the Sabaeans across the Red Sea and with the civilizations of the Nile Valley farther west along caravan routes.

Around the eighth century B.C.E., a kingdom known as D'mt was established in what is today northern Ethiopia and Eritrea, with its capital at Yeha in northern Ethiopia and which had extensive relations with the Sabeans in present-day Yemen across the Red Sea. [6] [7] After D'mt's decline around the fifth century B.C.E., the state of Aksum arose in the northern Ethiopian Highlands. It grew during the fourth century B.C.E. and came into prominence during the first century C.E., minting its own coins by the third century, converting in the fourth century to Christianity, as the second official Christian state (after Armenia) and the first country to feature the cross on its coins.

It grew to be one of the four greatest civilizations in the world, on a par with China, Persia, and Rome. In the seventh century , with the advent of Islam in Arabia, Aksum's trade and power began to decline and the center moved farther inland to the highlands of what is today Ethiopia.

Medieval history

During the medieval period, contemporary with and following the disintegration of the Axumite state, several states as well as tribal and clan lands emerged in the area known today as Eritrea. Between the eighth and thirteenth centuries, northern and western Eritrea largely came under the domination of the Beja, an Islamic, Cushitic people from northeastern Sudan. The Beja brought Islam to large parts of Eritrea and connected the region to the greater Islamic world dominated by the Ummayad Caliphate, followed by the Abbasid (and Mamluk) and later the Ottoman Empire. The Ummayads had taken the Dahlak Archipelago by 702.

In the main highland area and adjacent coastline of what is now Eritrea there emerged a Kingdom called Midir Bahr or Midri Bahri (Tigrinya). Parts of the southwestern lowlands were under the dominion of the Funj sultanate of Sinnar. Eastern areas under the control of the Afar since ancient times came to form part of the sultanate of Adal and, when that disintegrated, the coastal areas there became Ottoman vassals. As the kingdom of Midre Bahri and feudal rule weakened, the main highland areas would later be named Mereb Mellash, meaning "beyond the Mereb," defining the region as the area north of the Mareb River which to this day is a natural boundary between the modern states of Eritrea and Ethiopia. [8]

Roughly the same area also came to be referred to as Hamasien in the nineteenth century, before the invasion of Ethiopian King Yohannes IV, which immediately preceded and was partly repulsed by Italian colonialists. In these areas, feudal authority was particularly weak or nonexistent and the autonomy of the landowning peasantry was particularly strong; a kind of republic was exemplified by a set of customary laws legislated by elected councils of elders.

An Ottoman invading force under Suleiman I conquered Massawa in 1557, building what is now considered the 'old town' of Massawa on Batsi island. They also conquered the towns of Hergigo, and Debarwa, the capital city of the contemporary Bahr negus (ruler), Yeshaq. Suleiman's forces fought as far south as southeastern Tigray in Ethiopia before being repulsed. Yeshaq was able to retake much of what the Ottomans captured with Ethiopian assistance, but he later twice revolted against the emperor of Ethiopia with Ottoman support. By 1578, all revolts had ended, leaving the Ottomans in control of the important ports of Massawa and Hergigo and their environs, and leaving the province of Habesh to Beja Na'ibs (deputies).

The Ottomans maintained their dominion over the northern coastal areas for nearly three hundred years. Their possessions were left to their Egyptian heirs in 1865 and were taken over by the Italians in 1885.

Colonial era

A Roman Catholic priest by the name of Giuseppe Sapetto, acting on behalf of a Genovese shipping company called Rubattino, in 1869 purchased the locality of Assab from the local sultan. This happened in the same year as the opening of the Suez Canal.

During the Scramble for Africa, Italy began vying for a possession along the strategic coast of what was to become the world's busiest shipping lane. The government bought the Rubattino company's holdings and expanded its possessions northward along the Red Sea coast toward and beyond Massawa, encroaching on and quickly expelling previously "Egyptian" possessions. The Italians met with stiffer resistance in the Eritrean highlands from the army of the Ethiopian emperor. Nevertheless, the Italians consolidated their possessions into one colony, henceforth known as Eritrea, in 1890. The Italians remained the colonial power in Eritrea throughout the lifetime of fascism and the beginnings of World War II, when they were defeated by Allied forces in 1941 and Eritrea became a British protectorate.

After the war, a U.N. plebiscite voted for federation with Ethiopia, though Eritrea would have its own parliament and administration and would be represented in the federal parliament. In 1961 the 30-year Eritrean struggle for independence began after years of peaceful student protests against Ethiopian violation of Eritrean democratic rights and autonomy had culminated in violent repression and the emperor of Ethiopia's dissolution of the federation and declaration of Eritrea as a province of Ethiopia.

Struggle for independence

The Eritrean Liberation Front (ELF) was initially a conservative grass-roots movement dominated by Muslim lowlanders and thus received backing from Arab socialist governments such as Syria and Egypt. Ethiopia's imperial government received support from the United States. Internal divisions within the ELF based on religion, ethnicity, clan, and sometimes personalities and ideologies, led to the weakening and factioning of the ELF, from which sprang the Eritrean People's Liberation Front.

The EPLF professed Marxism and egalitarian values devoid of gender, religion, or ethnic bias. It came to be supported by a growing Eritrean diaspora. Bitter fighting broke out between the ELF and EPLF during the late 1970s and 1980s for dominance over Eritrea. The ELF continued to dominate the Eritrean landscape well into the 1970s, when the struggle for independence neared victory due to Ethiopia's internal turmoil caused by the socialist revolution against the monarchy.

The ELF's gains suffered when Ethiopia was taken over by the Derg, a Marxist military junta with backing from the Soviet Union and other communist countries. Nevertheless, Eritrean resistance continued, mainly in the northern parts of the country around the Sudanese border, where the most important supply lines were.

The numbers of the EPLF swelled in the 1980s, as did those of Ethiopian resistance movements with which the EPLF struck alliances to overthrow the communist Ethiopian regime. However, due to their Marxist orientation, neither of the resistance movements fighting Ethiopia's communist regime could count on U.S. or other support against the Soviet-backed might of the Ethiopian military, which was sub-Saharan Africa's largest outside South Africa. The EPLF relied largely on armaments captured from the Ethiopian army itself, as well as financial and political support from the Eritrean diaspora and the cooperation of neighboring states hostile to Ethiopia, such as Somalia and Sudan (although the support of the latter was briefly interrupted and turned into hostility in agreement with Ethiopia during the Gaafar Nimeiry administration between 1971 and 1985).

Drought, famine, and intensive offensives launched by the Ethiopian army on Eritrea took a heavy toll on the population— more than half a million fled to Sudan as refugees. Following the decline of the Soviet Union in 1989 and diminishing support for the Ethiopian war, Eritrean rebels advanced farther, capturing the port of Massawa. By early 1991 virtually all Eritrean territory had been liberated by the EPLF except the capital, whose only connection with the rest of government-held Ethiopia during the last year of the war was by an air-bridge. In 1991, Eritrean and Ethiopian rebels jointly held the Ethiopian capital under siege as the Ethiopian communist dictator Mengistu Haile Mariam fled to Zimbabwe, where he lives despite requests for extradition.

The Ethiopian army finally capitulated and Eritrea was completely in Eritrean hands on May 24, 1991, when the rebels marched into Asmara while Ethiopian rebels with Eritrean assistance overtook the government in Ethiopia. The new Ethiopian government conceded to Eritrea's demands to have an internationally (UN) supervised referendum. In April 1993, an overwhelming number of Eritreans voted for independence.

Independence

Upon Eritrea's declaration of independence, the leader of the EPLF, Isaias Afewerki, became Eritrea's first provisional president. Faced with limited economic resources and a country shattered by decades of war, the government embarked on a reconstruction and defense effort, later called the Warsai Yikalo Program, based on the labor of national servicemen and women. It is still ongoing and combines military service with construction, and teaching as well as agricultural work to improve the country's food security.

The government also attempts to tap into the resources of Eritreans living abroad by levying a 2 percent tax on the gross income of those who wish to gain full economic rights and access as citizens in Eritrea (land ownership, business licenses, etc) while at the same time encouraging tourism and investment both from Eritreans living abroad and people of other nationalities.

This has been complicated by Eritrea's tumultuous relations with its neighbors, lack of stability, and subsequent political problems.

Eritrea severed diplomatic relations with Sudan in 1994, claiming that the latter was hosting Islamic terrorist groups to destabilize Eritrea, and both countries entered an acrimonious relationship, each accusing the other of hosting various opposition rebel groups or "terrorists" and soliciting outside support to destabilize the other. Diplomatic relations were resumed in 2005, following a reconciliation agreement reached with the help of Qatar. Eritrea now plays a prominent role in the internal Sudanese peace and reconciliation effort.

Perhaps the conflict with the deepest impact on independent Eritrea was the renewed hostility with Ethiopia. In 1998, a border war over the town of Badme occurred. The war ended in 2000 with a negotiated agreement that set up an independent, UN-associated boundary commission to clearly identify the border.

The UN also established a demilitarized buffer zone within Eritrea running along the length of the disputed border. Ethiopia was to withdraw to positions held before the outbreak of hostilities. The verdict in April 2002 awarded Badme to Eritrea. However, Ethiopia refused to implement the ruling, resulting in the continuation of the UN mission and continued hostility between the two states, which do not have any diplomatic relations.

Diplomatic relations with Djibouti were briefly severed during the border war with Ethiopia in 1998 but were resumed in 2000.

Politics

The National Assembly of 150 seats (of which 75 were occupied by handpicked EPLF guerrilla members while the rest went to local candidates and diasporans more or less sympathetic to the regime) was formed in 1993, shortly after independence. It "elected" the current president, Isaias Afewerki. Since then, national elections have been periodically scheduled and canceled.

The constitution was ratified in 1997 but has not yet been implemented. The Transitional National Assembly does not meet.

Independent local sources of political information on domestic politics are scarce; in September 2001 the government closed down all the nation's privately owned print media, and outspoken critics of the government have been arrested and held without trial, according to various international observers, including Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International. In 2004 the U.S. State Department declared Eritrea a Country of Particular Concern for its record of religious persecution.

Foreign relations

Eritrea is a member of the African Union (AU), but it has withdrawn its representative to protest the AU's lack of leadership in facilitating the implementation of a binding decision demarcating the border between Eritrea and Ethiopia. Eritrea's relationship with the United States is complicated. Although the two nations have a close working relationship regarding the ongoing war on terror, tension has grown in other areas. Eritrea's relationship with Italy and the European Union has become equally strained in many areas.

Within the region, Eritrea's relations with Ethiopia turned from that of close alliance to a deadly rivalry that led to a war from May 1998 to June 2000 in which nineteen thousand Eritreans were killed.

External issues include an undemarcated border with Sudan, a war with Yemen over the Hanish Islands in 1996, as well as the border conflict with Ethiopia.

Despite the tension over the border with Sudan, Eritrea has been recognized as a broker for peace between the separate factions of the Sudanese civil war.

The dispute with Yemen was referred to the Permanent Court of Arbitration at The Hague, and both nations accepted the decision. Since 1996 both governments have remained wary of one another but relations are relatively normal.

Defining the border with Ethiopia is the primary external issue facing Eritrea. This led to a long and bloody border war between 1998 and 2000. Disagreements following the war have resulted in stalemate punctuated by periods of elevated tension and renewed threats of war. Central to the continuation of the stalemate is Ethiopia's failure to abide by the border delimitation ruling and reneging on its commitment to demarcation. The president of Eritrea urged the UN to take action against Ethiopia. The situation was further escalated by the continued efforts of the Eritrean and Ethiopian leaders to support each other's opposition movements.

On July 26, 2007, the Associated Press reported that Eritrea had been supplying weapons for a Somali insurgent group with ties to Al Qaeda. The incident fueled concerns that Somalia might become the grounds for a de facto war between Eritrea and Ethiopia, which sent forces to Somalia in December 2006 to help stabilize the country and reinforce the internationally backed government.

A UN Monitoring Group report indicated that Eritrea has played a key role in financing, funding, and arming the terror and insurgency activities in Somalia and is the primary source of support for that insurgency.

Military

The government has been slow to demobilize its military after the most recent border conflict with Ethiopia, although it formulated an ambitious demobilization plan with the participation of the World Bank. A pilot demobilization program involving 5,000 soldiers began in November 2001 and was to be followed immediately thereafter by a first phase in which some 65,000 soldiers would be demobilized. This was delayed repeatedly. In 2003, the government began to demobilize some of those slated for the first phase; however, the government maintains a "national service" program, which includes most of the male population between 18 and 40 and the female population between 18 and 27. The program essentially serves as a reserve force and can be mobilized quickly. There are estimates that one in twenty Eritreans actively serve in the military.

Administrative divisions

Eritrea is divided into six regions (zobas) and subdivided into districts. The geographical extent of the regions is based on their respective hydrological properties. This is a dual intent on the part of the Eritrean government: to provide each administration with sufficient control over its agricultural capacity and eliminate historical intra-regional conflicts.

Economy

The Eritrean economy is largely based on agriculture, which employs 80 percent of the population but currently may contribute as little as 12 percent to GDP. Agricultural exports include cotton, fruits and vegetables, hides, and meat, but farmers are largely dependent on rain-fed agriculture, and growth in this and other sectors is hampered by lack of a dependable water supply. Worker remittances and other private transfers from abroad currently contribute about 32 percent of GNP.

While in the past the government stated that it was committed to a market economy and privatization, the government and the ruling party maintain complete control of the economy. The government has imposed arbitrary and complex regulatory requirements that discourage investment from both foreign and domestic sources, and it often reclaims successful private enterprises and property.

After independence, Eritrea had established a growing and healthy economy. But the 1998-2000 war with Ethiopia had a major negative impact on the economy and discouraged investment. Eritrea lost many valuable economic assets, in particular during the last round of fighting in May-June 2000, when a significant portion of its territory in the agriculturally important west and south was occupied by Ethiopia. As a result of this last round of fighting, more than one million Eritreans were displaced, though by 2007 nearly all had been resettled. According to World Bank estimates, Eritreans also lost livestock worth some $225 million, and 55,000 homes worth $41 million were destroyed during the war. Damage to public buildings, including hospitals, is estimated at $24 million.

Much of the transportation and communication infrastructure is outmoded and deteriorating, although a large volume of intercity road-building activity is currently underway. The government sought international assistance for various development projects and mobilized young Eritreans serving in the national service to repair crumbling roads and dams. However, in 2005, the government asked the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) to cease operations in Eritrea.

According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), post-border war recovery was impaired by four consecutive years of recurrent drought that reduced the already low domestic food production capacity. The government reports that harvests have improved, but it provides no data to support these claims.

Eritrea currently suffers from large structural fiscal deficits caused by high levels of spending on defense, which have resulted in the stock of debt rising to unsustainable levels. Exports have collapsed due to strict controls on foreign currencies and trade, as well as a closed border with Ethiopia, which was the major trading partner for Eritrea prior to the war. In 2006, Eritrea normalized relations with Sudan and is beginning to open the border to trade between the two countries.

The port in Massawa has been rehabilitated and is being developed. In addition, the government has begun on a limited basis to export fish and sea cucumbers from the Red Sea to markets in Europe and Asia. A newly constructed airport in Massawa capable of handling jets could facilitate the export of high-value perishable seafood.

Eritrea's economic future depends upon its ability to overcome such fundamental social problems as illiteracy and low skills. Since subsistence agriculture is the main production activity, the division of labor is influenced by custom. The role of women is vital, but certain tasks, such as plowing and sowing, are conducted only by men. Animals are generally herded by young boys, while young girls assist in fetching water and firewood for the household.

The marginal industrial base in Eritrea provides the domestic market with textiles, shoes, food products, beverages, and building materials. If stable and peaceful development occurs, Eritrea might be able to create a considerable tourism industry based on the Dahlak islands in the Red Sea.

Eritrea has limited export-oriented industry, with livestock and salt being the main export goods.

Key positions in civil service and government are usually given to loyal veteran liberation fighters and party members.

A large share of trade and commercial activity is run by individuals from the Jeberti group (Muslim highlanders). They were traditionally denied land rights and had thus developed trading as a niche activity.

Demographics

Eritrea is a multilingual and multicultural country with two dominant religions (Sunni Islam and Oriental Orthodox Christianity) and nine ethnic groups: Tigrinya 50 percent, Tigre and Kunama 40 percent, Afar 4 percent, Saho (Red Sea coast dwellers) 3 percent, other 3 percent. Each nationality speaks a different native tongue but many of the minorities speak more than one language.

Languages

The country has three de facto official languages, the three working languages: Tigrinya, Arabic, and English. Italian is widely spoken among the older generation. The two language families that most of the languages stem from are the Semitic and Cushitic families. The Semitic languages in Eritrea are Arabic (spoken natively by the Rashaida Arabs), Tigre, Tigrinya, and the newly recognized Dahlik; these languages (primarily Tigre and Tigrinya) are spoken as a first language by over 80 percent of the population. The Cushitic languages in Eritrea are just as numerous, including Afar, Beja, Blin, and Saho. Kunama and Nara are also spoken in Eritrea and belong to the Nilo-Saharan language family.

Education

There are five levels of education in Eritrea: pre-primary, primary, middle, secondary, and post-secondary, but education is not compulsory. Two universities (University of Asmara and the Institute of Science and Technology), as well as several smaller colleges and technical schools, provide higher education. An estimated 45 percent of those eligible attend at the elementary level and 21 percent attend at the secondary level. Barriers to education in Eritrea include traditional taboos and school fees (for registration and materials).

Overall adult literacy is 58.6 percent, but the figure is 69.9 percent for male and 47.6 percent (2003 est.) for females.

Religion

Eritrea has two dominant religions, Christianity and Islam. Muslims, who make up about half the population, predominantly follow Sunni Islam. The Christians (another half) consist primarily of the Eritrean Orthodox Tewahdo Church, which is the local Eastern Orthodox church, but small groups of Roman Catholics, Protestants, and other denominations also exist.

Since the rural Eritrean community is deeply religious, the clergy and ulama have an influential position in the everyday lives of their followers. The main religious holidays of both main faiths are observed.

Since May 2002, the government of Eritrea has only officially recognized the Eritrean Orthodox Tewahdo Church, Sunni Islam, Catholicism, and the Evangelical Lutheran church. All other faiths and denominations are required to undergo a registration process that is so stringent as to effectively be prohibitive. Among other things, the government's registration system requires religious groups to submit personal information on their membership to be allowed to worship. The few organizations that have met all of the registration requirements have still not received official recognition.

Other faith groups, like Jehovah's Witnesses, the Bahá'í faith, the Seventh-day Adventists, and numerous Protestant denominations are not registered and cannot worship freely. They have effectively been banned, and harsh measures have been taken against their adherents. Many have been incarcerated for months or even years. None have been charged officially or given access to judicial process. In its 2006 religious freedom report, the U.S. State Department for the third year in a row named Eritrea a "Country of Particular Concern," designating it one of the worst violators of religious freedom in the world.

Culture

The Eritrean region has traditionally been a nexus for trade throughout the world. Because of this, the influence of diverse cultures can be seen throughout Eritrea, the most obvious of which is Italy. Throughout Asmara, there are small cafes serving beverages common to Italy. In Asmara, there is a clear merging of the Italian colonial influence with the traditional Tigrinya lifestyle. In the villages of Eritrea, these changes never took hold.

The main traditional food in Eritrean cuisine is tsebhi (stew) served with injera (flatbread made from teff, wheat, or sorghum), and hilbet (paste made from legumes, mainly lentils, faba beans). Kitcha fit-fit is also a staple of Eritrean cuisine. It consists of shredded, oiled, and spiced bread, often served with a scoop of fresh yogurt and topped with berbere (spice).

Traditional Eritrean dress is quite varied, with the Kunama traditionally dressing in brightly colored clothes while the Tigrinya and Tigre traditionally wear white costumes resembling traditional Oriental and Indian clothing. The Rashaida women are ornately bejeweled and scarfed.

Sports

Popular sports in Eritrea are football and bicycle racing. In recent years Eritrean athletes have seen increasing success in the international arena.

Almost unique on the African continent, the Tour of Eritrea is a bicycle race from the hot desert beaches of Massawa, up the winding mountain highway with its precipitous valleys and cliffs to the capital Asmara. From there, it continues downward onto the western plains of the Gash-Barka Zone, only to return back to Asmara from the south. This is, by far, the most popular sport in Eritrea, though long-distance running has garnered supporters. The momentum for long-distance running in Eritrea can be seen in the successes of Zersenay Tadesse and Mebrahtom (Meb) Keflezighi, both Olympians.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Central Intelligence Agency, Eritrea The World Factbook.

- ↑ Marie-Claude Simeone-Senelle, Les langues en Erythrée Arabian Humanities. Retrieved July 28, 2018.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Eritrea. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved July 28, 2018.

- ↑ E. Abbate, A. Albianelli, A. Azzaroli, M. Benvenuti, B. Tesfamariam, P. Bruni, N. Cipriani, R.J. Clarke, G. Ficcarelli, R. Macchiarelli, G. Napoleone, M. Papini, L. Rook, M. Sagri, T.M. Tecle, D. Torre, and I. Villa, A one-million-year-old Homo cranium from the Danakil (Afar) Depression of Eritrea, Nature 393(6684)(1998):458-60. Retrieved July 28, 2018.

- ↑ Rodolfo Fattovich, The development of urbanism in the northern Horn of Africa in ancient and medieval times The Development of Urbanism from a Global Perspective, edited by P.J.J. Sinclair (Uppsala University, 1996).

- ↑ Munro-Hay, S.C., Aksum: An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991, ISBN 978-0748602094), 57.

- ↑ Taddesse Tamrat, Church and state in Ethiopia, 1270-1527 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1972, ISBN 978-0198216711), 5-13.

- ↑ Daniel Kendie, The Five Dimensions of the Eritrean Conflict, 1941-2004: Deciphering the Geo-political Puzzle (Prairie View, TX: Daniel Kendie, 2005, ISBN 978-1932433470).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Cliffe, Lionel, and Basil Davidson. The Long struggle of Eritrea for independence and constructive peace. Nottingham, England: Spokesman, 1988. ISBN 978-0851244532

- Connell, Dan. Against all Odds: A Chronicle of the Eritrean Revolution With a New Afterword on the Postwar Transition. Trenton, NJ: Red Sea Press, 1997. ISBN 978-1569020463

- Connell, Dan. Building a New Nation: Collected Articles on the Eritrean Revolution (1983-2002). Trenton, NJ: Red Sea Press, 2004. ISBN 978-1569021989

- Connell, Dan. Conversations with Eritrean Political Prisoners. Trenton, NJ: Red Sea Press, 2005. ISBN 978-1569022351

- Connell, Dan. Rethinking Revolution: New Strategies for Democracy and Social Justice : the experiences of Eritrea, South Africa, Palestine and Nicaragua. Trenton, NJ: Red Sea Press, 2002. ISBN 1569021457

- Connell, Dan. Taking on the Superpowers: Collected Articles on the Eritrean Revolution, 1976-1982. Trenton, NJ: Red Sea Press, 2003. ISBN 978-1569021897

- Firebrace, James, and Stuart Holland. Never Kneel Down: Drought, Development and Liberation in Eritrea. Trenton, NJ: Red Sea Press, 1985. ISBN 0932415008

- Gebre-Medhin, Jordan. Peasants and Nationalism in Eritrea: A Critique of Ethiopian Studies. Trenton, NJ: Red Sea Press, 1989. ISBN 0932415385

- Hill, Justin. Ciao Asmara: A Classic Account of Contemporary Africa. London: Abacus, 2002. ISBN 978-0349115269

- Iyob, Ruth. The Eritrean Struggle for Independence: Domination, Resistance, Nationalism, 1941-1993. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997. ISBN 978-0521595919

- Jacquin-Berdal, Dominique, and Martin Plaut. Unfinished business: Eritrea and Ethiopia at war. Trenton, NJ: Red Sea Press, 2005. ISBN 978-1569022160

- Kendie, Daniel. The Five Dimensions of the Eritrean Conflict, 1941-2004: Deciphering the Geo-political Puzzle. Signature Book Printing, Inc, 2005. ISBN 1932433473

- Keneally, Thomas. To Asmara. New York, NY: Warner Books, 1989. ISBN 0446515426

- Kibreab, Gaim. Refugees and Development in Africa: The Case of Eritrea. Red Sea Press, 1987. ISBN 0932415261

- Kibreab, Gaim. Eritrea: A Dream Deferred. James Currey, 2009. ISBN 978-1847010087

- Killion, Tom. Historical dictionary of Eritrea. African historical dictionaries, no. 75. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 1998. ISBN 978-0585105703

- Munro-Hay, S. C. Aksum: An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991. ISBN 978-0748602094

- Ogbaselassie, Dr. G. Response to remarks by Mr. David Triesman, Britain's parliamentary under-secretary of state with responsibility for Africa. Demarcation Watch (January 10, 2006). Retrieved February 19, 2022.

- Pateman, Roy. Eritrea: Even the Stones are Burning. Trenton, NJ: Red Sea Press, 1998. ISBN 1569020574

- Phillipson, D. W. Ancient Ethiopia: Aksum, its Antecedents and Successors. London: British Museum Press, 1998. ISBN 0714125393

- Tamrat, Taddesse. Church and State in Ethiopia, 1270-1527. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1972. ISBN 978-0198216711

- Wrong, Michela. I Didn't Do It for You: How the World Betrayed a Small African Nation. New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers, 2005. ISBN 0060780924

External links

All links retrieved February 13, 2024.

- Demarcation Watch

- Countries and Their Cultures. Culture of Eritrea

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.