Indus Valley Civilization

The Indus Valley Civilization (IVC), was an ancient civilization thriving along the lower Indus River and the Ghaggar River-Hakra River in what is now Pakistan and western India from the twenty-eighth century B.C.E. to the eighteenth century B.C.E. Another name for this civilization is the Harappan Civilization of the Indus Valley, in reference to its first excavated city of Harappa. The Indus Valley Civilization stands as one of the great early civilizations, alongside ancient Egypt and Sumerian Civilization, as a place where human settlements organized into cities, invented a system of writing and supported an advanced culture. Hinduism and the culture of the Indian people can be regarded as having roots in the life and practices of this civilization.

This was a flourishing culture, with artistic and technological development, and no sign of slavery or exploitation of people. The civilization appears to have been stable and its demise was probably due to climactic change, although the Aryan invasion theory (see below) suggests that it fell prey to marauding newcomers.

Overview

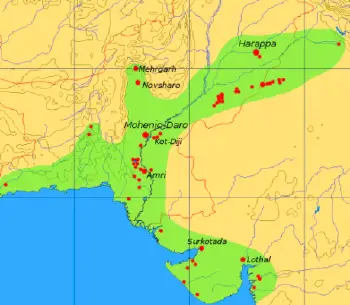

The Indus civilization peaked around 2500 B.C.E. in the western part of South Asia. Geographically, it was spread over an area of some 1,250,000 km², comprising the whole of modern-day Pakistan and parts of modern-day India and Afghanistan. The Indus civilization is among the world's earliest civilizations, contemporary to the great Bronze Age empires of Mesopotamia and ancient Egypt. It declined during the mid-second millennium B.C.E. and was forgotten until its rediscovery in the 1920s.

To date, over 1,052 cities and settlements have been found, mainly in the general region of the Indus River in Pakistan.

Additionally, there is some disputed evidence indicative of another large river, now long dried up, running parallel and to the east of the Indus. The dried-up river beds overlap with the Hakra channel in Pakistan, and the seasonal Ghaggar River in India. Over 140 ancient towns and cities belonging to the Indus Valley Civilization have been discovered along its course. A section of scholars claim that this was a major river during the third millennium B.C.E. and fourth millennium B.C.E., and propose that it may have been the Vedic Sarasvati River of the Rig Veda. Some of those who accept this hypothesis advocate designating the Indus Valley culture the "Sarasvati-Sindhu Civilization," Sindhu being the ancient name of the Indus River. Many reputed archaeologists dispute this view, arguing that the old and dry river died out during the Mesolithic Age at the latest, and was reduced to a seasonal stream thousands of years before the Vedic period.

There were Indus civilization settlements spread as far south as Mumbai (Bombay), as far east as Delhi, as far west as the Iranian border, and as far north as the Himalayas. Among the settlements were the major urban centers of Harappa and Mohenjo-daro, as well as Dholavira, Ganweriwala, Lothal, and Rakhigarhi. At its peak, the Indus civilization may have had a population of well over five million.

The native name of the Indus civilization may be preserved in the Sumerian Me-lah-ha, which Asko Parpola, editor of the Indus script corpus, identifies with the Dravidian Met-akam "high abode/country" (Proto-Dravidian). He further suggests that the Sanskrit word mleccha for "foreigner, barbarian, non-Aryan" may be derived from that name.

For all its achievements, the Indus civilization is still poorly understood. Its very existence was forgotten until the twentieth century. Its writing system, Indus script, remained undeciphered for a long time and it was generally accepted that it was a Dravidian language. In this view (see below) the original Dravidian inhabitants of India were forced South by the migration or invasion of Aryans, who brought with them proto-Vedic that later developed into Sanksrit. This is hotly disputed by contemporary Indian historians and linguists, who argue that the idea that foreigners always dominated India was conducive to European imperial ambitions.

Among the Indus civilization's mysteries, however, are fundamental questions, including its means of subsistence and the causes for its sudden disappearance beginning around 1900 B.C.E. Lack of information until recently led many scholars to negatively contrast the Indus Valley legacy with what is known about its contemporaries, Mesopotamia and ancient Egypt, implying that these have contributed more to human development.

Predecessors

The Indus civilization was predated by the first farming cultures in south Asia, which emerged in the hills of what is now called Balochistan, Pakistan, to the west of the Indus Valley. The best-known site of this culture is Mehrgarh, established around seventh millennium B.C.E. (6500 B.C.E.). These early farmers domesticated wheat and a variety of animals, including cattle. Pottery was in use by around sixth millennium B.C.E. (5500 B.C.E.). The Indus civilization grew out of this culture's technological base, as well as its geographic expansion into the alluvial plains of what are now the provinces of Sindh and Punjab in contemporary Pakistan.

By 4000 B.C.E., a distinctive, regional culture, called pre-Harappan, had emerged in this area. (It is called pre-Harappan because remains of this widespread culture are found in the early strata of Indus civilization cities.) Trade networks linked this culture with related regional cultures and distant sources of raw materials, including lapis lazuli and other materials for bead-making. Villagers had, by this time, domesticated numerous crops, including peas, sesame seeds, dates, and cotton, as well as a wide range of domestic animals, including the water buffalo, an animal that remains essential to intensive agricultural production throughout Asia today. Indus Valley was discovered in 1920 by R.D. Banerjee.

Emergence of Civilization

By twenty-sixth century B.C.E., some pre-Harappan settlements grew into cities containing thousands of people who were not primarily engaged in agriculture. Subsequently, a unified culture emerged throughout the area, bringing into conformity settlements that were separated by as much as 1,000 km and muting regional differences. So sudden was this culture's emergence that early scholars thought that it must have resulted from external conquest or human migration. Yet archaeologists have demonstrated that this culture did, in fact, arise from its pre-Harappan predecessor. The culture's sudden appearance appears to have been the result of planned, deliberate effort. For example, some settlements appear to have been deliberately rearranged to conform to a conscious, well-developed plan. For this reason, the Indus civilization is recognized to be the first to develop urban planning.

Cities

A sophisticated and technologically advanced urban culture is evident in the Indus Valley Civilization. The quality of municipal town planning suggests knowledge of urban planning and efficient municipal governments which placed a high priority on hygiene. The streets of major cities such as Mohenjo-daro or Harappa were laid out in a perfect grid pattern, comparable to that of present day New York City. The houses were protected from noise, odors, and thieves.

As seen in Harappa, Mohenjo-daro, and the recently discovered Rakhigarhi, this urban plan included the world's first urban sanitation systems. Within the city, individual homes or groups of homes obtained water from wells. From a room that appears to have been set aside for bathing, wastewater was directed to covered drains, which lined the major streets. Houses opened only to inner courtyards and smaller lanes.

The ancient Indus systems of sewage and drainage that were developed and used in cities throughout the Indus empire were far more advanced than any found in contemporary urban sites in the Middle East and even more efficient than those in some areas of modern India and Pakistan today. The advanced architecture of the Harappans is shown by their impressive dockyards, granaries, warehouses, brick platforms, and protective walls. The massive citadels of Indus cities that protected the Harappans from floods and attackers were larger than most Mesopotamian ziggurats.

The purpose of the "citadel" remains a matter of debate. In sharp contrast to this civilization's contemporaries, Mesopotamia and ancient Egypt, no large monumental structures were built. There is no conclusive evidence of palaces or templesâor, indeed, of kings, armies, or priests. Some structures are thought to have been granaries. Found at one city is an enormous well-built bath, which may have been a public bath. Although the "citadels" are walled, it is far from clear that these structures were defensive. They may have been built to divert flood waters.

Most city dwellers appear to have been traders or artisans, who lived with others pursuing the same occupation in well-defined neighborhoods. Materials from distant regions were used in the cities for constructing seals, beads, and other objects. Among the artifacts made were beautiful beads made of glazed stone called faĂŻence. The seals have images of animals, gods, etc., and inscriptions. Some of the seals were used to stamp clay on trade goods, but they probably had other uses. Although some houses were larger than others, Indus civilization cities were remarkable for their apparent egalitarianism. For example, all houses had access to water and drainage facilities. One gets the impression of a vast middle-class society.

Surprisingly, the archaeological record of the Indus civilization provides practically no evidence of armies, kings, slaves, social conflict, prisons, and other oft-negative traits that we traditionally associate with early civilization, although this could simply be due to the sheer completeness of its collapse and subsequent disappearance. If, however, there were neither slaves nor kings, a more egalitarian system of governance may have been practiced.

Science

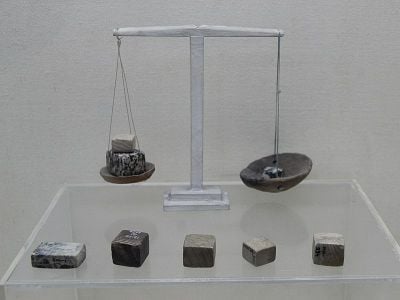

The people of the Indus civilization achieved great accuracy in measuring length, mass, and time. They were among the first to develop a system of uniform weights and measures. Their measurements were extremely precise. Their smallest division, which is marked on an ivory scale found in Lothal, was approximately 1.704 mm, the smallest division ever recorded on a scale of the Bronze Age. Harappan engineers followed the decimal division of measurement for all practical purposes, including the measurement of mass as revealed by their hexahedron weights.

Brick sizes were in a perfect ratio of 4:2:1, and the decimal system was used. Weights were based on units of 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100, 200, and 500, with each unit weighing approximately 28 grams, similar to the English ounce or Greek uncia, and smaller objects were weighed in similar ratios with the units of 0.871.

Unique Harappan inventions include an instrument which was used to measure whole sections of the horizon and the tidal dock. In addition, they evolved new techniques in metallurgy, and produced copper, bronze, lead, and tin. The engineering skill of the Harappans was remarkable, especially in building docks after a careful study of tides, waves, and currents.

In 2001, archaeologists studying the remains of two men from Mehrgarh, Pakistan made the startling discovery that the people of Indus civilization, even from the early Harappan periods, had knowledge of medicine and dentistry. The physical anthropologist that carried out the examinations, Professor Andrea Cucina from the University of Missouri-Columbia, made the discovery when he was cleaning the teeth from one of the men.

Arts

The people of Indus were great lovers of the fine arts, and especially dancing, painting, and sculpture. Various sculptures, seals, pottery, gold jewelry, terracotta figures, and other interesting works of art indicate that they had fine artistic sensibilities. Their art is highly realistic. The anatomical detail of much of their art is unique, and terracotta art is also noted for its extremely careful modeling of animal figures. Sir John Marshall once reacted with surprise when he saw the famous Indus statuettes:

When I first saw them I found it difficult to believe that they were prehistoric; they seemed to completely upset all established ideas about early art. Modeling such as this was unknown in the ancient world up to the Hellenistic age of Greece, and I thought, therefore, that some mistake must surely have been made; that these figures had found their way into levels some 3,000 years older than those to which they properly belonged. ⌠Now, in these statuettes, it is just this anatomical truth which is so startling; that makes us wonder whether, in this all-important matter, Greek artistry could possibly have been anticipated by the sculptors of a far-off age on the banks of the Indus (Marshall 2020).

Bronze, terracotta, and stone sculptures in dancing poses also reveal much about their art of dancing. Similarly, a harp-like instrument depicted on an Indus seal and two shell objects from Lothal confirm that stringed musical instruments were in use in the ancient Indus Valley Civilization. Today, much of the Indus art is considered advanced for their time period. Pillars were even sometimes topped with decorative capitals, such as the famous "Lions of Sarnath" Capital.

Religion

In the course of the second millennium B.C.E., remnants of the IVC's culture will have amalgamated with that of other peoples, likely contributing to what eventually resulted in the rise of historical Hinduism. Judging from the abundant figurines depicting female fertility that they left behind, indicate worship of a Mother goddess (compare Shakti and Kali). IVC seals depict animals, perhaps as the object of veneration, comparable to the zoomorphic aspects of some Hindu gods. Seals resembling Pashupati in a yogic posture have also been discovered.

Like Hindus today, Indus civilization people seemed to have placed a high value on bathing and personal cleanliness.

Economy

The Indus civilization's economy appears to have depended significantly on trade, which was facilitated by major advances in transport technology. These advances included bullock-driven carts that are identical to those seen throughout South Asia today, as well as boats. Most of these boats were probably small, flat-bottomed craft, perhaps driven by sail, similar to those one can see on the Indus River today; however, there is secondary evidence of sea-going craft. Archaeologists have discovered a massive, dredged canal and docking facility at the coastal city of Lothal.

Judging from the dispersal of Indus civilization artifacts, the trade networks, economically, integrated a huge area, including portions of Afghanistan, the coastal regions of Persia, northern and central India, and Mesopotamia.

Agriculture

The nature of the Indus civilization's agricultural system is still largely a matter of conjecture due to the paucity of information surviving through the ages. Some speculation is possible, however.

Indus civilization agriculture must have been highly productive; after all, it was capable of generating surpluses sufficient to support tens of thousands of urban residents who were not primarily engaged in agriculture. It relied on the considerable technological achievements of the pre-Harappan culture, including the plough. Still, very little is known about the farmers who supported the cities or their agricultural methods. Some of them undoubtedly made use of the fertile alluvial soil left by rivers after the flood season, but this simple method of agriculture is not thought to be productive enough to support cities. There is no evidence of irrigation, but such evidence could have been obliterated by repeated, catastrophic floods.

The Indus civilization appears to contradict the hydraulic despotism hypothesis of the origin of urban civilization and the state. According to this hypothesis, cities could not have arisen without irrigation systems capable of generating massive agricultural surpluses. To build these systems, a despotic, centralized state emerged that was capable of suppressing the social status of thousands of people and harnessing their labor as slaves. It is very difficult to square this hypothesis with what is known about the Indus civilization. There is no evidence of kings, slaves, or forced mobilization of labor.

It is often assumed that intensive agricultural production requires dams and canals. This assumption is easily refuted. Throughout Asia, rice farmers produce significant agricultural surpluses from terraced, hillside rice paddies, which result not from slavery but rather the accumulated labor of many generations of people. Instead of building canals, Indus civilization people may have built water diversion schemes, which, like terrace agriculture, can be elaborated by generations of small-scale labor investments. In addition, it is known that Indus civilization people practiced rainfall harvesting, a powerful technology that was brought to fruition by classical Indian civilization but nearly forgotten in the twentieth century. It should be remembered that Indus civilization people, like all peoples in South Asia, built their lives around the monsoon, a weather pattern in which the bulk of a year's rainfall occurs in a four-month period. At a recently discovered Indus civilization city in western India, archaeologists discovered a series of massive reservoirs, hewn from solid rock and designed to collect rainfall, that would have been capable of meeting the city's needs during the dry season.

Writing or Symbol System

It has long been claimed that the Indus Valley was the home of a literate civilization, but this has been challenged on linguistic and archaeological grounds. Well over 4,000 Indus symbols have been found on seals or ceramic pots and over a dozen other materials, including a 'signboard' that apparently once hung over the gate of the inner citadel of the Indus city of Dholavira. Typical Indus inscriptions are no more than four or five characters in length, most of which (aside from the Dholavira 'signboard') are exquisitely tiny; the longest on a single surface, which is less than 1 inch (2.54 cm) square, is 17 signs long; the longest on any object (found on three different faces of a mass-produced object) carries only 26 symbols. It has been recently pointed out that the brevity of the inscriptions is unparalleled in any known pre-modern literate society, including those that wrote extensively on leaves, bark, wood, cloth, wax, animal skins, and other perishable materials. The inscriptions found on seals were traditionally thought to be some form of Dravidian language.

Based partly on this evidence, a controversial paper by Farmer, Sproat, and Witzel (2004), which has been widely discussed in the world press, argued that the Indus system did not encode language, but was related instead to a variety of non-linguistic sign systems used extensively in the Near East. It has also been claimed on occasion that the symbols were exclusively used for economic transactions, but this claim leaves unexplained the appearance of Indus symbols on many ritual objects, many of which were mass produced in molds. No parallels to these mass-produced inscriptions are known in any other early ancient civilizations.

Photos of many of the thousands of extant inscriptions are published in three volumes of the Corpus of Indus Seals and Inscriptions (1987, 1991, 2010), edited by Asko Parpola and his colleagues. The third volume republished photos taken in the 1920s and 1930s of hundreds of lost or stolen inscriptions, along with many discovered in the last few decades.

A Contested Theory

In contrast to the findings of Farmer, Sproat and Witzel, work by the principal of Kendriya Vidyalaya, Farrak, West Bengal Natwar Jha (1996; see also Jha and Rajaram, 2000) on the seals has identified the language as a form of Vedic Sanskrit. His work also challenges the commonly accepted theory that the numeral system is of Arabic origin, since he identifies both an alphabet and a numeral system in the inscriptions. He argues that Babylonian and Egyptian mathematics owe a debt to the Indus Valley. His book, Vedic Glossary on Indus Seals argues that Greek evolved from old-Brahmi, which developed originally from the Indus Valley script. This reverses the accepted theory that both European languages and Sanksrit developed from a common proto-language and says that this was from a source closer to Europeâprobably Iran (hence Aryan).

Var's work is extremely significant since it also challenges the idea that the Indus Valley Civilization was pre-Aryan and that the Aryans invaded or migrated from the European zone. In the view of some Indian historians, such as N.S. Rajaram (Rajaram and Frawley 1997), no such invasion took place and the Aryans were indigenous to India. This alternative view to the âAryan invasionâ theory has been called the âcultural transformation hypothesis.â The distinction and idea of mutual antipathy between the darker-skinned Dravidians and the lighter-skinned Aryans was, according to Rajaram, a European invention to help legitimate their own rule, since they too were Aryans. He argues that âAryanâ simply means cultures, and can be claimed by people from any racial group. Sanksrit has no word for race. What Rajaram arguably does is reject one ethno-centered theory that favors Europe as the origin of civilization and replaces it with a theory that favors another ethnicity. Identity politics lies behind both views. In his view, the world owes the alphabet, numerals and much more besides to India, whose civilization is the most ancient and significant of them all. What this new theory does not explain is why what, from its artifacts, was obviously a flourishing civilization simply ceased, and remained forgotten for so long. Rajaram uses other arguments to explain North-South cultural differences. However, the linguistic difference between northern and southern Indian language may be difficult to explain apart from the theory of separate origins among two different peoples, Aryan and Dravidian.

This for some tends to confirm the theory that it was Aryans who invaded and somehow caused the civilization to collapse. Yet it can also be argued, even without the linguistic discoveries mentioned above, that many aspects of Aryan culture and religion owe something to the Indus Valley Civilization (see below). It is more likely that writing developed independently in up to seven locations and that the world does not owe a debt to any one of them singly. Ong (1992) lists India, China, Greece (Minoan or Mycenean 'Linear B' and later the Mayans, the Aztecs, the Mesopatamian city-states and the Egypt of the Pharaohs as locations where writing developed (85).

Some scholars argue that a sunken city, linked with the Indus Valley Civilization, off the coast of India was the Dwawka of the Mahabharata, and, dating this at 7500 B.C.E. or perhaps ever earlier, they make it a rival to Jericho (circa 10,000-11,000 B.C.E.) as the oldest city on earth (Howe 2002). Underwater archaeologists at India's National Institute of Ocean Technology first detected signs of an ancient submerged settlement in the Gulf of Cambay, off Gujarat, in May 2001 and carbon testing has dated wood recovered as 9,500 years old. Carved wood, pottery and pieces of sculpture have been retrieved. The underwater archaeological site is about 30 miles west of Surat in the Gulf of Khambhat (Cambay) in northwestern India. Some of Rajaram's writing is anti-Christian polemic and controverial but the leading Indologist, Klaus Klostermaier wrote the foreword to his 1997 text and seriously questions the Aryan-invasion theory in his own book, A Survey of Hinduism (1994) in which he concludes, âBoth the spatial and the temporal extent of the Indus civilization has expanded dramatically on the basis of new excavations and the dating of the Vedic age as well as the theory of an Aryan invasion of India has been shaken. We are required to completely reconsider not only certain aspects of Vedic India, but the entire relationship between Indus civilization and Vedic cultureâ (34). In a rebuttal of Jha and Rajarama's work, Witzel (2000) describes Rajaram as a revisionist historian and Hindutva (Indian nationalist/Hindu fundamentalist) propagandist.

Decline, collapse and legacy

Around the nineteenth century B.C.E. (1900 B.C.E.), signs began to emerge of mounting problems. People started to leave the cities. Those who remained were poorly nourished. By around the eighteenth century B.C.E. (1800 B.C.E.), most of the cities were abandoned. In the aftermath of the Indus civilization's collapse, regional cultures emerged, to varying degrees showing the influence of the Indus civilization. In the formerly great city of Harappa, burials have been found that correspond to a regional culture called the Cemetery H culture. At the same time, the Ochre Colored Pottery culture expands from Rajasthan into the Gangetic Plain.

It is in this context of the aftermath of a civilization's collapse that the Indo-Aryan migration into northern India is discussed. In the early twentieth century, this migration was forwarded in the guise of an "Aryan invasion," as noted above, and when the civilization was discovered in the 1920s, its collapse at precisely the time of the conjectured invasion was seen as an independent confirmation. In the words of the archaeologist Robert Eric Mortimer Wheeler (1890-1976), the Indo-Aryan war god Indra "stands accused" of the destruction. It is however far from certain whether the collapse of the IVC is a result of an Indo-Aryan migration. It seems rather likely that, to the contrary, the Indo-Aryan migration was as a result of the collapse, comparable with the decline of the Roman Empire and the incursions of relatively primitive peoples during the Migrations Period. It could also be argued that, if there was a movement of people from the North, then this migration took place gradually, so that the incoming culture absorbed much of what was already present. If Indra (a male God) was the dominant God of the incoming Aryans, then female aspects of God seem to have been venerated by the people of the Indus Valley, and in the form of Kali or Shakti, Saraswati, Parvati (the strength of the male deities) the feminine was restored to prominence. However, this (as noted above) may not adequately explain why the cities were abandoned.

A possible natural reason of the IVC's decline is connected with climate change. In 2600 B.C.E., the Indus Valley was verdant, forested, and teeming with wildlife. It was wetter, too; floods were a problem and appear, on more than one occasion, to have overwhelmed certain settlements. As a result, Indus civilization people supplemented their diet with hunting. By 1800 B.C.E., the climate is known to have changed. It became significantly cooler and drier. Thus, the flourishing life of these cities may have come to a natural end as new settlements in climactically more friendly environments were built. (Similar speculation surrounds Akbar the Great's abandonment of his new capital, Fatehpur-Sikri, almost immediately after building it.)

The crucial factor may have been the disappearance of substantial portions of the Ghaggar River-Hakra River system. A tectonic event may have diverted the system's sources toward the Ganges Plain, though there is some uncertainty about the date of this event. Such a statement may seem dubious if one does not realize that the transition between the Indus and Gangetic plains amounts to a matter of inches. The region in which the river's waters formerly arose is known to be geologically active, and there is evidence of major tectonic events at the time the Indus civilization collapsed. Although this particular factor is speculative, and not generally accepted, the decline of the IVC, as with any other civilization, will have been due to a combination of a variety of reasons. Klostermaier supports the climactic change thesis: "If, as Muller suggested, the Aryan invasion took place around 1500 B.C.E., it does not make much sense to locate villages along the banks of the by then dried up Sarasvati" (1994, 36).

In terms of assessing the legacy of the civilization, it is likely that some of the IVC's skills and technological achievements were adapted by others, whether or not by an invading Aryan people who, if the invasion theory holds, would have been more nomadic with less opportunity to develop technology. The IVC seems to have contributed to the development of Hinduism. If the IVC script did develop into Vedic-Sanksrit, then a huge debt is owed to the IVC because written language is the first essential building block for scholarship and learning, enabling more than what a few people can remember to be passed on.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Farmer, Steve, Richard Sproat, and Michael Witzel. 2004. "The Collapse of the Indus-Script Thesis: The Myth of a Literate Harappan Civilization" Electronic Journal of Vedic Studies 11(2): 19-57. Retrieved March 22, 2024.

- Howe, Linda Moulton. 2002. "Sunken City Off India's Coast - 7,500 B.C.E.?" Retrieved March 22, 2024.

- Jha, Natwar. 1996. Vedic Glossary on Indus Seals. Varanasi, India: Ganga-Kaveri Publishing. ISBN 978-8185694207

- Jha, Natwar, and Navaratna S. Rajaram. 2000. The Deciphered Indus Script: Methodology, Readings, Interpretations. New Delhi: Aditya Prakashan. ISBN 978-8177420159

- Klostermaier, Klaus K. 1994. A Survey of Hinduism. 2nd ed. Albany, NY: SUNY Press. ISBN 0791421104

- Marshall, John. 2020. Mohenjo-daro and the Indus Civilization. Gyan Publishing House. ISBN 978-8121207928

- Ong, Walter J. 1992. Orality and Literacy. London: Routledge. ISBN 0415281296

- Parpola, Asko, B. Pande, and Petteri Koskikallio (eds.). 2010. Corpus of Indus Seals and Inscriptions, Volume 3. Helsinki: Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia. Retrieved March 22, 2024.

- Rajaram, Navaratna S., and David Frawley. (foreword by Dr. Klaus K. Klostermaier). 1997. Vedic Aryans and the Origin of Civilization: A Literary and Scientific Perspective. Delhi: Voice of India. ISBN 8185990360

- Shaffer, Jim G. 1993. "The Indus Valley, Baluchistan and Helmand Traditions: Neolithic Through Bronze Age." In Chronologies in Old World Archaeology. R.W. Ehrich (ed.). 2 vols. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. 1:441-464, 2:425-446. ISBN 978-0226194479

- Witzel, Michael. 2000. "Horseplay in Harappa: The Indus Valley Decipherment Hoax" Retrieved March 22, 2024.

External links

All links retrieved November 28, 2024.

- The Ancient Indus Valley Civilization 3500 - 1700 B.C.E. Harappa.com

- Prehistoric dentistry evidence BBC

- Indus Valley Civilization World History Encyclopedia

- What was the Indus Valley Civilization? Live Science

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.