Hebrew Bible

- This article is about the term "Hebrew Bible." See also Tanakh (Jewish term) or Old Testament (Christian term).

Hebrew Bible is a term describing the common portions of the Jewish and Christian biblical canons. The term is considered neutral and is preferred in academic writing and interfaith settings over "Old Testament," which hints at the Christian doctrine of supersessionism, in which the "old" covenant of God with the Jews has been made obsolete by the "new" covenant with the Christians. The Jewish term for the Hebrew Bible is "Tanakh," a Hebrew acronym its component parts: the Torah, Prophets, and Writings. Few practicing Jews refer to their scriptures as the "Hebrew Bible," except in academic of interfaith contexts.

The word Hebrew in the name refers to either or both the Hebrew language or the Jewish people who have continuously used the Hebrew language in prayer and study. The Hebrew Bible" does not encompass the deuterocanonical books, also known as the Apocrypha, which are included in the canon of the Roman Catholic and Orthodox churches. Although the content of the Hebrew Bible corresponds to the versions of the Old Testament used by Protestant denominations, it differs from Christian Bibles in terms of the organization and division of books included.

Hebrew and Christian bibles

Objections by Jews and others to the term "Old Testament" is based on a long-standing Christian tradition that the covenant between God and the Jews was fundamentally inadequate to deal with the problem of sin. Technically referred to as supersessionism, this attitude dates back to the Epistle to the Hebrews, whose author claimed that God had established His "new covenant" with mankind through Jesus: "By calling this covenant 'new,' He has made the first one obsolete; and what is obsolete and aging will soon disappear" (Hebrews 8:13).

The term "New Testament," was later adopted by the Christian church to refer to their own scriptures and distinguish them from the sacred texts of Judaism, which the church also adopted as its own. Although most Christian denominations today formally reject the idea that God's covenant with the Jews was invalidated by Jesus' priestly ministry, most biblical scholars are sensitive to the historical implications of the term Old Testament and tend to avoid it in academic writing, as do those involved in interfaith dialog. The Hebrew term Tanakh is also sometimes used, but is less common than "Hebrew Bible" because of its unfamiliarity to non-experts.

The Jewish version of the Hebrew Bible differs from the Christian version in its original language, organization, division, and numbering of its books.

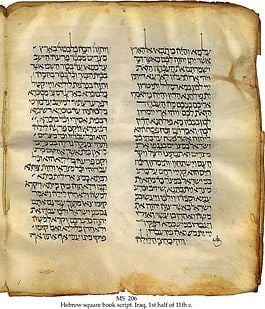

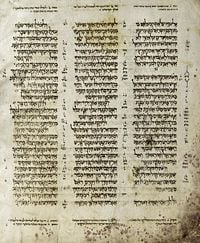

Language

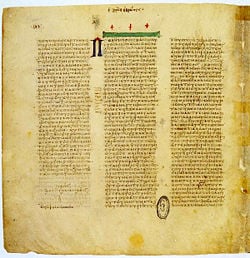

Although the content of Christian and Jewish versions of the Hebrew Bible is virtually the same, different translations are usually involved. Most Hebrew versions of the Tanakh, as well as English translations, are based on the Hebrew Masoretic text, while Christian versions or more influenced by the Latin Vulgate Bible and the Greek Septuagint (LXX) version. The Septuagint was created by Greek-speaking Jews about the second century B.C.E. in Alexandria, Egypt. It was widely used by diasporan Jews in the Greek and Roman world, but is influenced by the Greek language and philosophical concepts and was thus not preferred by rabbinical tradition. The Vulgate was created mostly by St. Jerome in the fifth century C.E., based on both Hebrew and Greek texts. The Masoretic is a purely Hebrew text.

Comparative study of the Latin, Greek, and Hebrew versions in recent centuries has produced useful insights, and the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls in the twentieth centuryâincluding nearly the entire corpus of the Tanakhâhave provided scholars with yet another ancient scriptural tradition. Comparisons of various texts and manuscripts are often included in footnotes in contemporary translations of the texts.

Organization

In terms of organization, Christian versions of the Hebrew Bible use a different order and division of the books than the Tanakh does. The word TaNaKh, in fact is an acronym based on the initial Hebrew letters of each of the text's three parts:

- Torah, meaning "Instruction." Also called the "Pentateuch" and the "Books of Moses," this part of the Tanakh follows the same order and division of books adopted in the Christian version.

- Nevi'im, meaning "Prophets." The Jewish tradition includes the "historical" books of Joshua, Kings and Samuel in this category.

- Ketuvim, meaning "Writings." These include this historical writings (Ezra-Nehemiah and the Book of Chronicles); wisdom books (Job, Ecclesiastes and Proverbs); poetry (Psalms, Lamentations and the Song of Solomon); and biographies (Ruth, Esther and Daniel).

The organization of this material in Christian Bibles places the Prophets after the writings and includes the Book of Daniel with the Prophets, placing it after Ezekiel. In addition, it groups Chronicles with Kings rather than considering it one of the Writings. The result is, among other things, that the last book of the Christian version is Malachi, while the last book of the Jewish version is Chronicles.

Numbering

The number of books also differs: 24 in the Jewish version and 39 in the Christian, due to the fact that some books which are united in Jewish tradition are divided in the Christian tradition.

Also, older Jewish versions of the Bible do not contain chapter and verse designations. Nevertheless, these are noted in modern editions so that verses may be easily located and cited. Although Samuel, Kings, and Chronicles remain as one book each, chapters of these books often stipulate "I or II" to prevent confusion, since the chapter numbering for these books follows their partition in the Christian textual tradition.

The adoption of the Christian chapter divisions by Jews began in the late middle ages in Spain, partially in the context of forced debates with priests in Europe. Nevertheless, because it proved useful this convention continued to be included by Jews in most Hebrew editions of the biblical books.

Apocrypha

Finally, the Catholic and Orthodox "Old Testament" contains six books not included in the Tanakh, as well as material included in the books of Daniel, Esther, and other books which does not appear in the Hebrew Bible. Known usually as the Apocrypha, their technical term is the deuterocanonical books (literally "canonized secondly" meaning canonized later).

Early editions of the King James Version of the Bible in English also included them. These books as also known as "intratestimental literature," due to their being written after the time of the prophets but before the time of Jesus.

Canonization

Although the Sadducees and Pharisees of the first century C.E. disagreed on much, they seem to have agreed that certain scriptures were to be considered sacred. Some Pharisees developed a tradition requiring that one's hands be washed after handling sacred scriptures. The introduction of this custom would naturally tend to fix the limits of the canon, for only contact with books that were actually used or regarded as fit for use in the synagogue would demand such a washing of the hands. What was read in public worship constituted the canon.

Among the works eliminated by this process were many of the writings that maintained their place in the Alexandrian Jewish tradition, having been brought to Egypt and translated from the original Hebrew or Aramaic, such as Baruch, Sirach, I Maccabees, Tobit and Judith; as well works such as the Book of Jubilees, Psalms of Solomon, Assumption of Moses, and the Apocalypses of Enoch, Noah, Baruch, Ezra, and others. Some of these works, meanwhile had gained acceptance in Christian circles and were thus adopted as the Apocrypha, while losing their place of spiritual significance among all but a few Jewish readers until recently.[1]

Order of the books of the Tanakh

Torah

Prophets

- Joshua

- Judges

- Books of Samuel (I & II)

- Kings (I & II)

- Isaiah

- Jeremiah

- Ezekiel

- The Twelve Minor Prophets

Writings

- Psalms

- Proverbs

- Job

- Song of Songs

- Ruth

- Lamentations

- Ecclesiastes

- Esther

- Daniel

- Ezra-Nehemiah

- Chronicles (I & II)

See also

- Tanakh

- Torah

- Masoretic Text

- Biblical canon

- Rabbinic literature

- Septuagint

Notes

- â These canonical Christian Apocrypha of the Old Testament, however, should not be confused with the New Testament Apocrypha. The latter include works of both orthodox and heretical writers, while the former are all deemed worthy of Christian readers by Catholic and Orthodox tradition.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Boadt, Lawrence, Helga B. Croner, and Leon Klenicki. Biblical Studies, Meeting Ground of Jews and Christians. Studies in Judaism and Christianity. New York: Paulist Press, 1980. ISBN 9780809123445

- Collins, John Joseph. Introduction to the Hebrew Bible. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2004. ISBN 9780800629915

- Rabin, Elliott. Understanding the Hebrew Bible: A Reader's Guide. Jersey City, N.J.: KTAV, 2006. ISBN 9780881258714

- Toorn, K. van der. Scribal Culture and the Making of the Hebrew Bible. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2007.

External links

All links retrieved June 25, 2024.

- Unicode/XML Westminster Leningrad Codex www.tanach.us

- Judaica Press Translation (online translation of Tanakh and Rashi's entire commentary) www.chabad.org

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.