Spain

| Reino de Espa√Īano Kingdom of Spain |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Motto: "Plus Ultra" (Latin) "Further Beyond" |

||||||

| Anthem: "Marcha Real" (Spanish) [1] "Royal March" |

||||||

| Location of Spain within the European Union

|

||||||

| Capital (and largest city) | Madrid 40¬į26‚Ä≤N 3¬į42‚Ä≤W | |||||

| Official languages | Spanish[2] | |||||

| Recognized regional languages | Basque, Catalan/Valencian, Galician and Occitan | |||||

| Demonym | Spanish, Spaniard | |||||

| Government | Unitary parliamentary democracy and Constitutional monarchy | |||||

|  -  | King | Felipe VI | ||||

|  -  | Prime Minister | Pedro Sánchez | ||||

| Legislature | Cortes Generales | |||||

|  -  | Upper House | Senate | ||||

|  -  | Lower House | Congress of Deputies | ||||

| Formation | 15th century  | |||||

|  -  |  Traditional date | 569 (ascension to the throne of Liuvigild)  | ||||

|  -  |  Dynastic | 1479  | ||||

|  -  |  De facto | 1516  | ||||

|  -  |  De jure | 1715  | ||||

|  -  |  Nation state | 1812  | ||||

|  -  |  Constitutional democracy | 1978  | ||||

| EU accession | 1 January 1986 | |||||

| Area | ||||||

|  -  | Total | 504,030 km² (51st) 195,364 sq mi  |

||||

|  -  | Water (%) | 1.04 | ||||

| Population | ||||||

|  -  | 2016 census | 46,698,151 |

||||

|  -  | Density | 92/km² (112th) 240/sq mi |

||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2018 estimate | |||||

|  -  | Total | $1.864 trillion[4] (16th) | ||||

|  -  | Per capita | $40,290[4] (31st) | ||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2018 estimate | |||||

|  -  | Total | $1.506 trillion[4] (12th) | ||||

|  -  | Per capita | $32,559[4] (30th) | ||||

| Gini (2016) | 34.5[5]  | |||||

| Currency | Euro (‚ā¨)[6] (EUR) |

|||||

| Time zone | CET[7] (UTC+1) | |||||

|  -  | Summer (DST) | CEST[8] (UTC+2) | ||||

| Internet TLD | .es[9] | |||||

| Calling code | [[+34]] | |||||

Spain, officially the Kingdom of Spain (Spanish: Reino de Espa√Īa), is a country located in Southern Europe, with two small exclaves in North Africa (both bordering Morocco). It is the largest of the three sovereign nations that make up the Iberian Peninsula‚ÄĒthe others are Portugal and the microstate of Andorra.

Spain has been a constitutional monarchy with a parliamentary democracy since 1975, when the authoritarian Franco regime ended. It is a developed country with the ninth-largest economy in the world.

Spain's history includes long periods of religious struggle involving Catholicism, Islam, and Judaism, and is known for the Spanish Inquisition, the massacre and widespread expulsions of Jews, and as a bastion of Roman Catholicism.

Today it is a nation that can claim success in the management of its autonomous communities, as each is allowed to function highly independently. Spain's decentralized government operates as an individualized system of support to those communities. Another modern success for this nation is its transition from dictatorship to democracy and it can thus serve as an example to many nations in this respect.

Geography

Spain, from the Latin name Hispania, is located southwest of France, with the Bay of Biscay to the north, North Atlantic Ocean and Portugal to the west, Gibraltar to the south, the Mediterranean Sea to the south-east. The Pyrenees Mountains form the border with France. The tiny principality of Andorra is located on the French border.

Spain includes two autonomous cities - Ceuta and Melillathe - in North Africa, the Balearic Islands in the Mediterranean Sea, the Canary Islands in the Atlantic Ocean and a number of uninhabited islands on the Mediterranean side of the strait of Gibraltar, known as Plazas de soberan√≠a, such as the Chafarine islands, the isle of Albor√°n, the "rocks" (pe√Īones) of V√©lez and Alhucemas, and the tiny Isla Perejil. In the northeast along the Pyrenees, a small exclave town called Ll√≠via in Catalonia is surrounded by French territory.

At 194,884 square miles (504,782 square kilometers), Spain is the world's 51st-largest country (after Thailand). It is comparable in size to Turkmenistan, and somewhat larger than the U.S. state of California.

Spain forms more than 80 percent of the Iberian Peninsula. Mainland Spain is dominated by a large plateau, the Meseta Central, which is divided by the roughly west-east Sistema Central mountain range. The Cordillera Cantábrica mountains border the Meseta to the north, the Iberian Cordillera to the northeast and east, the Sierra Morena to the south, while the lower mountains of the Portuguese frontier and Spanish Galicia are located to the northwest. In the southeast, the Sistema Penibético runs parallel to the coast to merge with the Iberian Cordillera. Along the Mediterranean seaboard there are coastal plains, some with lagoons (such as Albufera, south of Valencia). The Balearic Islands in the Mediterranean are are a portion of the Baetic Cordillera. The Canary Islands are of volcanic origin and contain Spain's highest point, Teide Peak, which rises to 12,198 feet (3718 metres) on the island of Tenerife.

Except for the subtropical Canary Islands, Spain can be divided into climate areas: a Mediterranean climate, a climate dominated by the Atlantic Ocean, and (in the inner areas) a continental climate with hotter summers and colder winters. The continental climate zone, which covers most of peninsular Spain, is characterized by wide diurnal and seasonal variations in temperature and by low, irregular rainfall with high rates of evaporation that leave the land arid. Annual rainfall generally is 12 inches to 25 inches (300mm to 640mm). Continental winters are cold 30.2¬įF (-1¬įC), with strong winds. Summers are warm and cloudless, producing average daytime temperatures that reach 70¬įF (21¬įC) in the northern Meseta, and 75¬įF to 80¬įF (24¬įC to 27¬įC) in the southern Meseta. The Ebro Basin, at a lower altitude, is hot during the summer, and temperatures can exceed 104¬įF (40¬įC).

An oceanic climate prevails in the northern part of the country, often called "Green Spain," from the Pyrenees to the northwest region, characterized by relatively mild winters, warm but not hot summers, and generally abundant rainfall spread out over the year. Temperatures vary slightly, both on a diurnal and a seasonal basis. The moderating effects of the sea, however, abate in the inland areas, where temperatures are 48¬įF to 65¬įF (9¬įC to 18¬įC) more extreme than temperatures on the coast.

The Mediterranean climate region roughly extends from the Andalusian Plain along the southern and eastern coasts up to the Pyrenees, on the seaward side of the mountain ranges that parallel the coast. Total rainfall there is lower than in the rest of Spain, and it is concentrated in the late autumn-winter period. Temperatures in January normally average 50¬įF to 55.4¬įF (10¬įC to 13¬įC) in most of the Mediterranean region, and they are 48¬įF (9¬įC) colder in the northeastern coastal area near Barcelona. Temperatures in July and August average 72¬įF to 80¬įF (22¬įC to 27¬įC) on the coast and 84¬įF to 86¬įF (29¬įC to 31¬įC) farther inland, with low humidity. The Mediterranean region is marked by Leveche winds: hot, dry, easterly or southeasterly air currents that originate over North Africa.

The generally warm and relatively dry summers have led to a culture in which a lot of life is lived outdoors, whether on a patio in the courtyard of a building or on a public plaza. In Madrid, many of the most popular nightclubs move for several months in the summer to an outdoor terraza much farther from the city center than their indoor winter location, continuing in a way the older tradition of the verbena (fair). In the Mediterranean areas (and in the Canary Islands), outdoor meals are served year-round.

Despite apparent aridity, the Iberian Peninsula has a dense network of roughly 1800 rivers and streams, all of which, except the Ebro, drain into the Atlantic Ocean. Three rank among Europe's longest. The Tagus is 626 miles (1007km), the Ebro is 565 miles (909 km), and the Douro at 556 miles (895km). The Guadiana and the Guadalquivir are 508 miles (818km) and 408 miles (657km) long, respectively. The Tagus, the Douro, and the Guadiana, reach the Atlantic Ocean in Portugal.

Spain has a wider variety of natural vegetation than any other European country‚ÄĒ8000 species have been cataloged. Humid areas of the north have deciduous oak, chestnut, elm, beech, and poplar, as well as varieties of pine. The dry southern region has pine, juniper, and other evergreens, particularly the ilex and cork oak, and drought-resistant shrubs. The Meseta and Andalusia has steppe vegetation. The Canaries, so named for wild dogs (canariae insulae) once found there, as well as a small, yellow-tinged finch. Human habitation means few wild species of animals remain in mainland Spain.

Natural resources include coal, lignite, iron ore, uranium, mercury, pyrites, fluorspar, gypsum, zinc, lead, tungsten, copper, kaolin, potash, hydropower, as well as arable land.

Natural hazards include periodic droughts and wildfires. Environmental issues include pollution of the Mediterranean Sea from raw sewage and effluents from the offshore production of oil and gas, water quality and quantity, air pollution, deforestation, and desertification.

Madrid, with a population of 5,904,041 in 2006, is the capital and largest city of Spain. The city is located on the river Manzanares in the center of the country, between the autonomous communities of Castile and León and Castile-La Mancha. Due to its economic output, standard of living, and market size, Madrid is considered the major financial center of the Iberian Peninsula; it hosts the head offices of the vast majority of the major Spanish companies. Other most populous metropolitan regions are: Barcelona 5,300,701,Valencia 1,623,724, Sevilla 1,317,098, Málaga 1,074,074, and Bilbao 946,829.

History

Pre-history

The Iberian Peninsula, comprising modern Spain and Portugal, has been inhabited by hominin species for at least half a million years. Many of the best preserved prehistoric remains are in the Atapuerca region, rich with limestone caves. Among these sites is the cave of Gran Dolina, where six hominin skeletons, dated between 780,000 and one million years ago, were found in 1994. Cro-Magnons began arriving in the Iberian Peninsula from the Pyrenees some 35,000 years ago. The more conspicuous sign of prehistoric human settlements are the famous cave paintings in the northern Spanish Altamira (cave), which were done ca. 15,000 B.C.E. Iberia has numerous ruins of megalithic monuments created during the Neolithic period (5000 B.C.E.) and continued into the Chalcolithic or Copper Age.

Celtic societies

Early in the first millennium B.C.E., several waves of Celts invaded Portugal from central Europe and intermarried with the local Iberian people, forming the Celtiberian ethnic group, with many tribes. Chief among these tribes were the Lusitanians, the Calaicians or Gallaeci and the Cynetes or Conii; among the lesser tribes were the Bracari, Celtici, Coelerni, Equaesi, Grovii, Interamici, Leuni, Luanqui, Limici, Narbasi, Nemetati, Paesuri, Quaquerni, Seurbi, Tamagani, Tapoli, Turduli, Turduli Veteres, Turdulorum Oppida, Turodi, and Zoelae). There were in this era, some small, semipermanent commercial coastal settlements founded by the Greeks and, in the Algarve, Tavira founded by Phoenicians-Carthaginians.

Urban culture

The earliest Iberian urban culture documented is that of the semi-mythical southern city of Tartessos, pre-1100 B.C.E. The seafaring Phoenicians, Greeks and Carthaginians successively settled along the Mediterranean coast and founded trading colonies there over a period of several centuries. Around 1100 B.C.E., Phoenician merchants founded the trading colony of Gadir (modern day C√°diz) near Tartessos. In the ninth century B.C.E., the first Greek colonies, such as Emporion (modern Emp√ļries), were founded along the Mediterranean coast on the East, leaving the south coast to the Phoenicians. The Greeks are responsible for the name Iberia, apparently after the river Iber (Ebro in Spanish). In the sixth century B.C.E., the Carthaginians arrived in Iberia while struggling first with the Greeks and shortly after with the Romans for control of the Western Mediterranean. Their most important colony was Carthago Nova (Latin name of modern day Cartagena).

Roman Empire

The Romans arrived in the Iberian peninsula during the Second Punic war in the second century B.C.E., and annexed it under Augustus after two centuries of war with the tenacious Celtic and Iberian tribes (from whom they copied the short sword known as falcata). These, along with the Phoenician, Greek and Carthaginian coastal colonies, became the province of Hispania. It was divided into Hispania Ulterior and Hispania Citerior during the late Roman Republic; and, during the Roman Empire, Hispania Taraconensis in the northeast, Hispania Baetica in the south and Lusitania (province with capital in the city of Emerita Augusta) in the southwest.

Hispania supplied Rome with food, olive oil, wine and metal. The emperors Trajan, Hadrian, Marcus Aurelius and Theodosius I, the philosopher Seneca and the poets Martial, Quintilian and Lucan were born in Spain. The Spanish Bishops held the Council at Elvira in 306. The collapse of the Western Roman empire did not lead to the same wholesale destruction of Western classical society as happened in areas like Britain, Gaul and Germania Inferior during the Dark Ages, even if the institutions, infrastructure and economy did suffer considerable degradation. Spain's present languages, its religion, and the basis of its laws originate from this period. The centuries of uninterrupted Roman rule and settlement left a deep and enduring imprint upon the culture of Spain.

Germanic invasions

The first hordes of Barbarians to invade Hispania arrived in the fifth century, as the Roman empire decayed. The tribes of Goths, Visigoths, Swebians (Suebi), Alans, Asdings and Vandals, all of Germanic origin, arrived to Spain by crossing the Pyrenees mountain range. This led to the establishment of the Swebian Kingdom in Gallaecia, in the northwest, and the Visigothic Kingdom elsewhere. (For a while, the Germans lived under their law while the much more numerous Spaniards continued more or less to live under Roman law.) The Visigothic Kingdom eventually encompassed the entire Iberian Peninsula with the Catholic conversion of the Goth monarchs. The famous horseshoe arch, which was adapted and perfected by the later Muslim era builders was in fact originally an example of Visigothic art.

Muslim conquest

In the eighth century, nearly all the Iberian peninsula, which had been under Visigothic rule, was quickly conquered (711‚Äď718), by mainly Berber Muslims, who had crossed over from North Africa, led by Tariq ibn Ziyad. Visigothic Spain was the last of a series of lands conquered in a great westward charge by the Islamically inspired armies of the Umayyad empire. They continued north until they were defeated in central France at the Battle of Tours in 732. Astonishingly the invasion started off as an invitation from a Visigoth faction within Spain for support. But instead the Moorish army, having defeated King Roderic proceeded to conquer the peninsula for itself. The Roman Catholic populace, unimpressed with the constant feuding of the Visigothic leaders, often stood apart from the fighting, welcoming the new rulers, thereby forging the basis of the distinctly Spanish-Muslim culture of Al-Andalus. Only three small counties in the mountains of the north of Spain managed to cling to their independence: Asturias, Navarra and Aragon, which eventually became kingdoms.

The Muslim emirate stopped Charlemagne's massive forces at Saragossa in 777 C.E. and, after a serious Viking attack, established effective defenses. Christian Spain struck back from mountain redoubts by seizing the lands north of the Duero river, and the Franks were able to seize Barcelona (801) and the Spanish Marches), but otherwise, the Christians were unable to make headway against the superior forces of Al-Andalus for several centuries. It was only in the eleventh century that the break up of Al-Andalus led to the creation of the Taifa kingdoms, which were often at war, and became vulnerable to the consolidating power of Spain's Christian kingdoms.

The Moorish capital was Córdoba, in southern Spain, the richest and most sophisticated city in western Europe. During this time large populations of Jews, Christians and Muslims lived in close quarters, and at its peak some non-Muslims were appointed to high offices. Cordoba produced exquisite architecture and art, and Muslim and Jewish scholars helped revive classical Greek philosophy, mathematics and science. After the death of Al-Hakam II in 976, invasions of stricter Muslim groups led to persecutions of non-Muslims, forcing some (including Muslim scholars) to seek safety in the then still relatively tolerant city of Toledo after its Christian reconquest in 1085.

Islamic conquest did not involve the systematic conversion of the much larger conquered population to Islam, while Christians and Jews were recognized under Islam as "peoples of the book", and so given dhimmi status. Christians and Jews were free to practice their religion, but faced certain restrictions and financial burdens. Conversion to Islam steadily increased, as it offered social and economic and political advantages. Merchants, nobles, large landowners, and other local elites were usually among the first to convert. By the eleventh century Muslims are believed to have outnumbered Christians in Al-Andalus.

Crops and farming techniques introduced by the Arabs, led to a remarkable expansion of agriculture, which had been in decline since Roman times. Outside the cities, the mixture of large estates and small farms that existed in Roman times remained largely intact because Muslim leaders rarely dispossessed landowners.

Christian reconquest

The long period of expansion of the Christian kingdoms, beginning in 722 with the Muslim defeat in the battle of Covadonga and the creation of the Christian kingdom of Asturias, only 11 years after the Moorish invasion, is called the Reconquista. As early as 739 Muslim forces were driven out of Galicia, which came to host one of Christianity's holiest sites, Santiago de Compostela. Areas in the northern mountains and around Barcelona were soon captured by Frankish and local forces, providing a base for Spain's Christians. The 1085 conquest of the central city of Toledo largely completed the reconquest of the northern half of Spain.

The Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa in 1212 heralded the collapse of the great Moorish strongholds in the south, most notably Córdoba in 1236 and Seville in 1248. Within a few years of this nearly the whole of the Iberian peninsula had been reconquered, leaving only the Muslim enclave of Granada as a small tributary state in the south. Surrounded by Christian Castile but afraid of another invasion from Muslim northern Africa, it clung tenaciously to its isolated mountain splendor for two and half centuries.

The reconquest from the Muslims is one of the most significant events in Spanish history since the fall of the Roman Empire. Arabic quickly lost its place in southern Spain's life, and was replaced by Castilian. The process of religious conversion which started with the arrival of the Moors was reversed from the mid-thirteenth century as the Reconquista was advancing south: as this happened the Muslim population either fled or forcefully converted into Catholicism, mosques and synagogues were converted into churches.

Kingdom of Spain

By the fifteenth century, the most important Christian kingdoms were the Kingdom of Castile (occupying a northern and central portion of the Iberian Peninsula) and the Kingdom of Aragon (occupying northeastern portions of the peninsula). The rulers of these two kingdoms were allied with dynastic families in Portugal, France, and other neighboring kingdoms. The death of Henry IV in 1474 set off a struggle for power between contenders for the throne of Castile, including Juana la Beltraneja, supported by Portugal and France, and Queen Isabella I, supported by the Kingdom of Aragon, and by the Castilian nobility.

The marriage of Isabella I of Castile (1451-1504) and Ferdinand II of Aragón (1452-1516), in 1469, in Valladolid, united both crowns and effectively led to the creation of the Kingdom of Spain, at the dawn of the modern era. Isabella of Castile and Ferdinand of Aragon were known as the "Catholic Monarchs" (Spanish: los Reyes Católicos), a title bestowed on them by Pope Alexander VI. Besides the War of the Castillian Succession (1475-1479), they oversaw the final stages of the Reconquista of Iberian territory from the Moors with the conquest of Granada, conquered the Canary Islands and expelled the Jews and Muslims from Spain under the Alhambra decree (1492). They authorized the expedition of Christopher Columbus, who became the first European to reach the New World (since Leif Ericson) which led to an influx of wealth into Spain, funding the coffers of the new state that would prove to be a dominant power of Europe for the next two centuries.

Until the late fifteenth century, Castile and Le√≥n, Arag√≥n and Navarre were independent states, with independent languages, monarchs, armies and, in the case of Aragon and Castile, two empires: the former with one in the Mediterranean and the latter with a new, rapidly growing, one in the Americas. The process of political unification continued into the early sixteenth century. With the union of Castile and Arag√≥n in 1479 and the subsequent conquest of Granada in 1492 and Navarre in 1512, the word Spain (Espa√Īa, in Spanish) began being used only to refer to the new unified kingdom and not to the whole of Hispania.

Isabella ensured long-term political stability in Spain by arranging strategic marriages for each of her five children. Her firstborn, a daughter named Isabella, married Afonso of Portugal, but Isabella soon died before giving birth to an heir. Juana, Isabella’s second daughter, married Philip the Handsome, the son of Maximilian I, King of Bohemia (Austria) and became entitled to the crown of the Holy Roman Emperor. Isabella’s first and only son, Juan, married Margaret of Austria, maintaining ties with the Habsburg dynasty, on which Spain relied heavily. Her fourth child, Maria, married Manuel I of Portugal, strengthening the link forged by her older sister’s marriage. Her fifth child, Catherine, married Henry VIII, King of England and was mother to Queen Mary I.

Jews expelled

If until the thirteenth century religious minorities (Jews and Muslims) had enjoyed quite some tolerance in Castille and Aragon. But by 1391, large numbers of Jews were killed in every major city, and over the next century, half of the estimated 200,000 Spanish Jews converted to Christianity. At Ferdinand's urging, the Spanish Inquisition was established in 1478, and in 1492, the Alhambra Decree ordered the remaining Jews to convert or face expulsion from Spain. The number of Jews actually expelled is estimated to be anywhere from 40,000 to 120,000 people. Over the following decades, Muslims faced the same fate and about 60 years after the Jews, they were also compelled to convert or be expelled. Gypsies also endure a tragic fate. All Gypsy males were forced to serve in galleys between the age of 18 and 26 - which was equivalent to a death sentence - but the majority managed to hide and avoid arrest.

Spanish Empire

In the sixteenth century, Spain and Portugal led European global exploration and colonial expansion and the opening of trade routes across the oceans, with trade flourishing across the Atlantic between Spain and the Americas and across the Pacific between East Asia and Mexico via the Philippines. Conquistadors toppled the Aztec, the Inca, and Maya civilizations, and laid claim to vast stretches of land in North and South America. For a time, the Spanish Empire dominated the oceans with its experienced navy and ruled the European battlefield with its fearsome and well trained infantry, the famous tercios. Spain enjoyed a cultural golden age in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

This American empire was at first a disappointment, as the natives had little to trade. The diseases that arrived with the colonizers devastated the native populations, especially in the densely populated regions of the Aztec, Maya and Inca civilizations, and this reduced economic potential of conquered areas. In the 1520s, large-scale extraction of silver from the rich deposits of Mexico's Guanajuato began, to be greatly augmented by the silver mines in Mexico's Zacatecas and Peru's Potosi from 1546. These silver shipments re-oriented the Spanish economy, leading to the importation of luxuries and grain. They also became indispensable in financing the military capability of Habsburg Spain in its long series of European and North African wars, though, with the exception of a few years in the seventeenth century, Spain itself (Castile in particular) was by far the most important source of revenue. From the beginning of the incorporation of the Portuguese empire in 1580 (lost in 1640) until the loss of its American colonies in the nineteenth century, Spain maintained the largest empire in the world. Spanish thinkers formulated some of the first modern thoughts on natural law, sovereignty, international law, war, and economics; there were even questions about the legitimacy of imperialism.

Charles V

The Spanish Empire reached its maximum extent in Europe under Charles I of Spain (1500-1558), who was also (also known as Charles V) emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. The grandson of Isabella and Ferdinand, Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, who was also called Carlos I of Castille and Aragon, became king in 1516, and the history of Spain became even more firmly enmeshed with the dynastic struggles in Europe. The king was not often in Spain, and as he approached the end of his life he made provision for the division of the Habsburg inheritance into two parts: on the one hand Spain, and its possessions in the Mediterranean and overseas, and the Holy Roman Empire itself on the other. The Habsburg possessions in The Netherlands also remained with the Spanish crown.

Phillip II and the wars of religion

The division of the Habsburg inheritance was to prove a difficulty for his successor Philip II of Spain (1527-1598), who became king on Charles V's abdication in 1556. Spain largely escaped the religious conflicts that were raging throughout the rest of Europe, and remained firmly Roman Catholic. Philip saw himself as a champion of Catholicism, both against the Ottoman Turks and the heretics. In the 1560s, plans to consolidate control of the Netherlands led to unrest, which gradually led to the Calvinist leadership of the revolt and the Eighty Years' War (1568-1648). This conflict consumed much Spanish expenditure, and led to an attempt to conquer England ‚Äď a cautious supporter of the Dutch ‚Äď in the unsuccessful Spanish Armada (1588), an early battle in the Anglo-Spanish War (1585‚Äď1604) and war with France (1590‚Äď1598).

Despite these problems, the growing inflow of American silver from mid sixteenth century, the justified military reputation of the Spanish infantry and even the navy quickly recovering from its Armada disaster, made Spain the leading European power. The Iberian Union with Portugal in 1580 not only unified the peninsula, but added that country's worldwide resources to the Spanish crown. However, economic and administrative problems multiplied in Castile, and the weakness of the native economy became evident in the following century: rising inflation, the expulsion of the Jews and Moors from Spain, and the growing dependency of Spain on the gold and silver imports, combined to cause several bankruptcies that caused economic crisis in the country, especially in heavily burdened Castile.

The coastal villages of Spain and Balearic Islands were frequently attacked by Barbary pirates from North Africa, the Formentera was even temporarily left by its population and long stretches of the Spanish and Italian coasts, a relatively short distance across a calm sea from the pirates North African lairs, were almost completely abandoned by their inhabitants. The most famous corsair was the Turkish Barbarossa ("Redbeard"). According to Robert Davis between 1 million and 1.25 million Europeans were captured by North African pirates and sold as slaves in North Africa and Ottoman Empire between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries. This was gradually alleviated as Spain and other Christian powers began to check Muslim naval dominance in the Mediterranean after the 1571 victory at Lepanto.

Philip II died in 1598, and was succeeded by his son Philip III, in whose reign a ten-year truce with the Dutch was overshadowed in 1618 by Spain's involvement in the European-wide Thirty Years' War (1618-1648). It was the reign in which the geniuses of Cervantes and El Greco flourished. Philip III was succeeded in 1621 by his son Philip IV of Spain. Much of the policy was conducted by the minister Gaspar de Guzm√°n, Conde de Olivares. In 1640, with the war in central Europe having no clear winner except the French, both Portugal and Catalonia rebelled. Portugal was lost to the crown for good, in Italy and most of Catalonia, French forces were expelled and Catalonia's independence suppressed. In the reign of Philip's mentally retarded son and successor Charles II, Spain was essentially left leaderless and was gradually being reduced to a second-rank power.

The Habsburg dynasty became extinct in Spain and the War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1714) ensued in which the other European powers tried to assume control of the Spanish monarchy. King Louis XIV of France eventually "won" the War of Spanish Succession, and control of Spain passed to the Bourbon dynasty but the peace deals that followed included the relinquishing of the right to unite the French and Spanish thrones and the partitioning of Spain's European empire.

Golden age

The Spanish Golden Age (in Spanish, Siglo de Oro) was a period of flourishing arts and letters in the Spanish Empire, coinciding with the political decline and fall of the Habsburgs (Philip III, Philip IV and Charles II). The Habsburgs, both in Spain and Austria, were great patrons of art in their countries. El Escorial, the great royal monastery built by King Philip II of Spain, invited the attention of some of Europe's greatest architects and painters. Diego Vel√°zquez, regarded as one of the most influential painters of European history and a greatly respected artist in his own time, cultivated a relationship with King Philip IV and his chief minister, the Count-Duke of Olivares, leaving us several portraits that demonstrate his style and skill. El Greco, another respected Spanish artist from the period, infused Spanish art with the styles of the Italian renaissance and helped create a uniquely Spanish style of painting. Some of Spain's greatest music is regarded as having been written in the period. Such composers as Tom√°s Luis de Victoria, Luis de Mil√°n and Alonso Lobo helped to shape Renaissance music and the styles of counterpoint and polychoral music, and their influence lasted far into the Baroque period. Spanish literature blossomed as well, most famously demonstrated in the work of Miguel de Cervantes, the author of Don Quixote de la Mancha. Spain's most prolific playwright, Lope de Vega, wrote possibly as many as one thousand plays over his lifetime, over four hundred of which survive to the present day.

Absolutism and the eighteenth century

Philip V, the first Bourbon king, of French origin, signed the Decreto de Nueva Planta in 1715, a new law that revoked most of the historical rights and privileges of the different kingdoms that conformed the Spanish Crown, unifying them under the laws of Castile, where the Cortes had been more receptive to the royal wish. Spain became culturally and politically a follower of absolutist France. The rule of the Spanish Bourbons continued under Ferdinand VI and Charles III.

Under the rule of Charles III (1716-1788) and his ministers, Spain embarked on a program of enlightened despotism that brought Spain a new prosperity in the middle of the eighteenth century. After losing alongside France against the United Kingdom in the Seven Years' War (1756-1763), Spain recouped most of her territorial losses in the American Revolutionary War. The reforming spirit of Charles III was extinguished in the reign of his son, Charles IV (1748-1819), seen by some as mentally handicapped.

During most of the eighteenth century Spain made a long, slow recovery, with an expansion of the iron and steel industries in the Basque Country, a growth in ship building, some increase in trade and a recovery in food production and a gradual recovery of population in Castile. In the last two decades of the century, with the ending of Cadiz's royally granted monopoly, trade experienced an extraordinary growth (from a relatively low base) and even witnessed the initial steps of an industrialization of the textile industry in Catalonia. Spain's effective military assistance to the rebellious British colonies in the American War of Independence won it renewed international standing. But Spain continued to seriously lag in the enlightenment and mercantile developments transforming other parts of Europe, most notably in the United Kingdom, France, the Low Countries. The chaos unleashed by the Napoleonic intervention would cause this gap to widen greatly.

Napoleonic Wars

Spain initially sided against France in the Napoleonic Wars (1799-1815), but the defeat of her army early in the war led to Charles IV's pragmatic decision to align with the revolutionary French. A major Franco-Spanish fleet was annihilated, at the decisive Battle of Trafalgar in 1805, prompting the vacillating king of Spain to reconsider his alliance with France. Spain broke off from the Continental System temporarily, and Napoleon‚ÄĒaggravated with the Bourbon kings of Spain‚ÄĒinvaded and deposed Charles. The Spanish people vigorously resisted the move and juntas were formed across Spain that pronounced themselves in favor of Charles's son Ferdinand.

Spain was put under a British blockade, and her colonies‚ÄĒfor the first time separated from their colonial rulers‚ÄĒbegan to trade independently with Britain. The defeat of the British invasions of the River Plate in South America emboldened an independent attitude in Spain's American colonies. Initially, the juntas declared their support for Ferdinand, expecting greater autonomy from Madrid under the liberal constitution that the juntas had drafted. The Cortes took refuge at C√°diz. In 1812 the C√°diz Cortes created the first modern Spanish constitution, the Constitution of 1812.

The British, led by the Duke of Wellington, fought Napoleon's forces in the Peninsular War, with Joseph Bonaparte ruling as king at Madrid. The brutal war was one of the first guerrilla wars in modern Western history; French supply lines stretching across Spain were mauled repeatedly by Spanish guerrillas. The war in Iberia fluctuated repeatedly, with Wellington spending several years behind his fortresses in Portugal while launching occasional campaigns into Spain. The French were decisively defeated at the Battle of Vitoria in 1813, and the following year, Ferdinand was restored as King of Spain.

1812 constitution

The Spanish Constitution of 1812 was promulgated by the C√°diz Cortes, the national legislative assembly of Spain acting while in refuge. At the time the Cortes adopted the Constitution, they were taking refuge at C√°diz from the Peninsular War. Several basic principles were soon ratified: that sovereignty resides in the nation, the legitimacy of Ferdinand VII as King of Spain, and the inviolability of the deputies. The Cortes of C√°diz worked feverishly, and the first written Spanish constitution was promulgated in the city of C√°diz on March 12, 1812.

Although the juntas that had forced the French to leave Spain had sworn by the liberal Constitution of 1812, Ferdinand VII (1784-1833) openly believed that it was too liberal for the country. On his return to Spain, he refused to swear by it himself, and he continued to rule in the authoritarian fashion of his forebears. Although Spain accepted this, the policy was not warmly accepted in Spain's empire in the New World. Revolution broke out. Spain‚ÄĒnearly bankrupt from the war with France and the reconstruction of the country‚ÄĒwas unable to pay her soldiers, and in 1820, an expedition intended for the colonies revolted in Cadiz. When armies throughout Spain pronounced themselves in sympathy with the rebels, led by Rafael del Riego, Ferdinand relented and was forced to accept the liberal Constitution of 1812. Ferdinand himself was placed under effective house arrest.

The three years of liberal rule that followed coincided with a civil war in Spain that would typify Spanish politics for the next century. The liberal government, which reminded European statesmen entirely too much of the governments of the French Revolution, was looked on with hostility by the Congress of Verona in 1822, and France was authorized to intervene. France crushed the liberal government with massive force, and Ferdinand was restored as absolute monarch. The American colonies, however, were completely lost; in 1824, the last Spanish army on the American mainland was defeated at the Battle of Ayacucho in southern Peru.

The power vacuum between 1808 and 1814 had enabled local juntas in the Spanish colonies in America to rule independently. Starting as early as 1809, the continent started freeing itself from Spanish rule; by 1825 with the exceptions of Cuba, Puerto Rico and the Philippines, and a number of Pacific Islands Spain had lost all its colonies in Latin America.

Carlist wars

A period of uneasy peace followed in Spain for the next decade. Having borne only a female heir presumptive, it appeared that Ferdinand would be succeeded by his brother, Infante Carlos of Spain. While Ferdinand aligned with the conservatives, fearing another national insurrection, he did not view the reactionary policies of his brother as a viable option. Ferdinand‚ÄĒresisting the wishes of his brother‚ÄĒdecreed the Pragmatic Sanction of 1830, enabling his daughter Isabella to become Queen. Carlos, who made known his intent to resist the sanction, fled to Portugal. Ferdinand's death in 1833 and the accession of Isabella (only three years old at the time) as Queen of Spain sparked the First Carlist War. Carlos invaded Spain and attracted support from reactionaries and conservatives in Spain; Isabella's mother, Maria Cristina of Bourbon-Two Sicilies, was named regent until her daughter came of age.

The insurrection seemed to have been crushed by the end of the year; Maria Cristina's armies, called "Cristino" forces, had driven the Carlist armies from most of the Basque country. Carlos then named the Basque general Tom√°s de Zumalac√°rregui his commander-in-chief. Zumalac√°rregui resuscitated the Carlist cause, and by 1835 had driven the Cristino armies to the Ebro River and transformed the Carlist army from a demoralized band into a professional army of 30,000 of quality superior to the government forces. Zumalac√°rregui's death in 1835 changed the Carlists' fortunes. The Cristinos found a capable general in Baldomero Espartero. His victory at the Battle of Luchana (1836) turned the tide of the war, and in 1839, the Convention of Vergara put an end to the first Carlist insurrection.

Espartero, operating on his popularity as a war hero and his sobriquet "Pacifier of Spain," demanded liberal reforms from Maria Cristina. The Queen Regent preferred to resign and let Espartero become regent instead. Espartero's liberal reforms were opposed, then, by moderates; the former general's heavy-handedness caused a series of sporadic uprisings throughout the country from various quarters, all of which were bloodily suppressed. He was overthrown as regent in 1843 by Ramón María Narváez, a moderate, who was in turn perceived as too reactionary. Another Carlist uprising, the Matiners' War, was launched in 1846 in Catalonia, but it was poorly organized and suppressed by 1849.

Isabella's reign

Isabella II of Spain took a more active role in government after she came of age, but she was immensely unpopular throughout her reign. In 1856, she attempted to form a pan-national coalition, the Union Liberal, under the leadership of Leopoldo O'Donnell who had already marched on Madrid that year and deposed another Espartero ministry. Isabella's plan failed and cost Isabella more prestige and favor with the people. Isabella launched a successful war against Morocco in 1860 that stabilized her popularity in Spain. However, a campaign to reconquer Peru and Chile during the Chincha Islands War proved disastrous and Spain suffered defeat before the determined South American powers. In 1866, a revolt led by Juan Prim was suppressed, but it was becoming increasingly clear that the people of Spain were upset with Isabella's approach to governance. In 1868, the Glorious Revolution broke out when the progresista generals Francisco Serrano and Juan Prim revolted against her, and defeated her moderado generals at the Battle of Alcolea. Isabella was driven into exile in Paris. The revolution culminated in the democratic constitution of 1869. Cuba revolted against Spanish rule, in the Ten Years’ War (1868).

Liberal King Amadeus I

Revolution and anarchy broke out in Spain in the two years that followed; it was only in 1870 that the Cortes declared that Spain would have a king again. As it turned out, this decision, played an important role in European and thus world history, for a German prince's candidacy to the Spanish throne and French opposition to him served as the immediate motive for the Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871). Amadeus of Savoy (1845-1890) was selected, and he was duly crowned King of Spain early the following year. Amadeus‚ÄĒa liberal who swore by the liberal constitution the Cortes promulgated‚ÄĒwas faced immediately with the incredible task of bringing the disparate political ideologies of Spain to one table. He was plagued by internecine strife, not merely between Spaniards but within Spanish parties.

First Spanish Republic

The First Spanish Republic started with the abdication as King of Spain on February 10, 1873, of Amadeo I. Amadeus famously declared the people of Spain to be ungovernable, and fled the country. The next day, February 11, the republic was declared by a parliamentary majority made up of radicals, republicans and democrats. The republic was immediately under siege from all quarters‚ÄĒthe Carlists were the most immediate threat, launching a violent insurrection after their poor showing in the 1872 elections. There were calls for socialist revolution from the International Workingmen's Association, revolts and unrest in the autonomous regions of Navarre and Catalonia, and pressure from the Roman Catholic Church against the fledgling republic. The republic lasted 23 months and had five presidents.

Monarchy restored

Although the former queen, Isabella II was still alive, she recognized that she was too divisive as a leader, and abdicated in 1870 in favor of her son, Alfonso. The Republican armies in Spain‚ÄĒwhich were resisting a Carlist insurrection‚ÄĒpledged their allegiance to Alfonso. The Republic was dissolved and Antonio Canovas del Castillo, a trusted advisor to the king, was named Prime Minister on New Year's Eve, 1874. Alfonso XII was duly crowned of Spain in 1875. The Carlist insurrection was put down vigorously by the new king, who took an active role in the war and rapidly gained the support of most of his countrymen. A system of turnos was established in which the liberals, led by Pr√°xedes Mateo Sagasta and the conservatives, led by Antonio Canovas del Castillo, alternated in control of the government. A modicum of stability and economic progress was restored to Spain during Alfonso XII's rule. His death in 1885, followed by the assassination of Canovas del Castillo in 1897, destabilized the government.

At the end of the nineteenth century, Spain lost all of its remaining old colonies in the Caribbean and Asia-Pacific regions, including Cuba, Puerto Rico, Philippines, and Guam to the United States after unwittingly and unwillingly being thrust into the Spanish-American War of 1898. In 1899 Spain sold its remaining Pacific possessions to Germany.

World War I

World War I was a global military conflict which took place primarily in Europe from 1914 to 1918. Over 40 million casualties resulted, including approximately 20 million military and civilian deaths. Spain's neutrality in the First World War allowed it to become a supplier of material for both sides to its great advantage, prompting an economic boom in Spain. The outbreak of Spanish influenza in Spain and elsewhere, along with a major economic slowdown in the postwar period, hit Spain particularly hard, and the country went into debt. A major worker's strike was suppressed in 1919.

Rivera dictatorship

Mistreatment of the Moorish population in Spanish Morocco led to an uprising and the loss of this North African possession except for the enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla in 1921. King Alfonso XIII decided to appoint General Miguel Primo de Rivera (1870-1930) as prime minister, ending the period of constitutional monarchy in Spain. For seven years (1923-1930) he was a dictator, ending the turno system of alternating parties. In joint action with France, the Moroccan territory was recovered (1925‚Äď1927), but in 1930 bankruptcy and massive unpopularity left the king no option but to force Primo de Rivera to resign. Disgusted with the king's involvement in his dictatorship, the urban population voted for republican parties in the municipal elections of April 1931. The king fled without abdicating and a republic was established.

Second Spanish Republic

Under the Second Spanish Republic, women were allowed to vote in general elections for the first time. The republic devolved substantial autonomy to the Basque Country and to Catalonia. The first governments of the republic, were center-left, headed by Niceto Alcal√°-Zamora, and Manuel Aza√Īa. Economic turmoil, substantial debt inherited from the Primo de Rivera regime, and fractious, rapidly changing governing coalitions led to serious political unrest. In 1933, the right-wing CEDA won power; an armed rising of workers of October 1934, which reached its greatest intensity in Asturias and Catalonia, was forcefully put down by the CEDA government. This in turn energized political movements across the spectrum in Spain, including a revived anarchist movement and new reactionary and fascist groups, including the Falange and a revived Carlist movement.

Spanish Civil War

In the 1930s, Spanish politics were polarized at the left and right of the political spectrum. The left wing favored class struggle, land reform, autonomy to the regions and reduction in church and monarchist power. The right-wing groups, the largest of which was CEDA, a right wing Roman Catholic coalition, held opposing views on most issues. In 1936, the left united in the Popular Front and was elected to power. However, this coalition, dominated by the centre-left, was undermined both by the revolutionary groups such as the anarchist CNT and FAI and by anti-democratic far-right groups such as the Falange and the Carlists. Political violence resumed. There were gunfights over strikes, landless laborers began to seize land, church officials were killed and churches burnt. On the other side, right wing militias (such as the Falange) and gunmen hired by employers assassinated left wing activists. The right wing of the country and high ranking figures in the army began to plan a coup. When Falangist politician José Calvo-Sotelo was shot by Republican police, they used it as a signal to act.

On July 17, 1936, General Francisco Franco (1892-1975) led the colonial army from Morocco to attack the mainland, while another force from the north under General Sanjurjo moved south from Navarre. Franco intended to seize power immediately, but resistance by Republicans in Madrid, Barcelona, Valencia, the Basque country, and elsewhere created a prolonged civil war. Before long, much of the south and west was under the control of the Nationalists, whose regular Army of Africa was the most professional force available to either side. Both sides received foreign military aid, the Nationalists, from Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy and Portugal, the Republic from the USSR and communist organized volunteers in the International Brigades.

The Siege of the Alc√°zar at Toledo from July to September, 1936, was a turning point, with the Nationalists winning after a long siege. The Republicans managed to hold out in Madrid, despite a Nationalist assault in November 1936, and frustrated subsequent offensives against the capital at Jarama and Guadalajara in 1937. Soon, though, the Nationalists began to erode their territory, starving Madrid and making inroads into the east. The north, including the Basque country fell in late 1937 and the Aragon front collapsed shortly afterwards. The bombing of Guernica (April 26, 1937) was probably the most infamous event of the war and inspired Picasso's picture. It was used as a testing ground for the German Luftwaffe's Condor Legion. The Battle of the Ebro in July-November 1938 was the final desperate attempt by the Republicans to turn the tide. When this failed and Barcelona fell to the Nationalists in early 1939, it was clear the war was over. The remaining Republican fronts collapsed and Madrid fell in March 1939.

The war, which cost between 300,000 to 1,000,000 lives, ended with the destruction of the Republic and the accession of Francisco Franco as dictator of Spain. Franco amalgamated all the right wing parties into a reconstituted Falange and banned the left-wing and Republican parties and trade unions. The conduct of the war was brutal on both sides, with massacres of civilians and prisoners being widespread. After the war, many thousands of Republicans were imprisoned and up to 150,000 were executed between 1939 and 1943. Many other Republicans remained in exile for the entire Franco period.

World War II

The Spanish Civil War officially ended on April 1, 1939, the day that dictator Francisco Franco announced the end of hostilities. The Republican regime had been defeated and Franco became undisputed leader of the "Spanish State." In September 1939, World War II broke out in Europe. After the collapse of France in June 1940, Spain adopted a pro-Axis non-belligerency stance (for example, he offered Spanish naval facilities to German ships). Adolf Hitler met Franco in Hendaye, France (October 23, 1940), to discuss the Spanish entry in the war joining the Axis. Franco's demands (food, military equipment, Gibraltar, French North Africa, etc.) proved too much and no agreement was reached. Contributing to the disagreement was an ongoing dispute over German mining rights in Spain. Some historians argue that Franco made demands that he knew Hitler would not accede to in order to stay out of the war. Other historians argue that he simply had nothing to offer the Germans. Franco did send volunteer troops to fight communism joining the Axis armies on the Eastern Front against the Soviet Union. The unit name was the División Azul, or Blue Division, after the Falange's party color, whose members were known as "blueshirts." At the same time, Spanish diplomats in the Axis countries actively protected Jews and Spain itself became a safe haven for Jewish refugees, as Franco refused to implement anti-Semitic laws, as demanded by the Axis. Franco returned to complete neutrality in 1943, when the tide of the war had turned decisively against Hitler's Germany.

The Franco dictatorship

Although Franco's regime has often been characterized as fascist, and that it had the consistent support of fascists in Spain and abroad, most scholars described him rather as a nationalist conservative or as a proponent of Clerical Fascism. Some features in Francoism contrast it with totalitarian regimes, in particular the lack of will to create a "new man." However, the Movimiento Nacional did involve the whole population in its various organizations. The emphasis was on order and stability.

In 1940, the "Vertical Trade Union" was created, which followed the corporatist ideas of José Antonio Primo de Rivera. It was the only legal syndicate, and was under government control. Other syndicates and political parties were forbidden and strongly repressed. In accordance with Franco's nationalist principles, only Spanish was recognized as an official language of the country, although millions of the country's citizens spoke other native languages (Catalan, Basque and Galician being the most numerous). The use of these languages was discouraged, and most public uses were forbidden. This policy was initially very strict, but relaxed with time.

Although a self-proclaimed monarchist, Franco had no particular desire for a king, due to his strained relations with the legitimate heir of the Crown, Don Juan de Borb√≥n. Therefore, he left the throne vacant, with himself as de facto regent. He wore the uniform of a captain general (a rank traditionally reserved for the king), resided in the Pardo Palace, appropriated the kingly privilege of walking beneath a canopy, and his portrait appeared on most Spanish coins. Indeed, although his formal titles were Jefe del Estado (Head of State) and General√≠simo de los Ej√©rcitos Espa√Īoles (Highest General of the Spanish Armed Forces), he was referred to as Caudillo de Espa√Īa por la gracia de Dios, (by the grace of God, the Leader of Spain).

Isolation

After the war, the Allies used Spain's ties to the Axis powers to keep it from joining the United Nations. Franco's government was seen, especially by Soviet countries but also by the United Kingdom, to be a remnant of the central European fascist regimes. A UN resolution condemning Franco's government followed. The resolution encouraged countries to remove their ambassadors in Spain, and established the basis for measures against Spain if the government remained authoritarian. Only Portugal and a few Latin-American countries, like Juan Perón's Argentina, refused to comply.

An embargo against the Francoist regime resulted in 1946 - including the closure of the French border - with little success, as it boosted support for the regime. The most fanatic partisans said the embargo was a machination of Jews and Freemasons against Catholic Spain. In 1947, the president of Argentina, Juan Perón sent his wife Eva Duarte de Perón with much-needed food supplies. The Spaniards, and Franco himself, heartily welcomed Evita.

After World War II, the Spanish economy was still in disarray. Rationing cards were still used as late as 1952. War and economic isolation prompted the regime to move towards autarky (economic self-sufficiency), a movement welcomed by Falangists. Franco reduced imports, moved towards self-sufficiency, state-controlled production and commercialization of first order goods, state-funded industry and construction of infrastructure heavily damaged during the Civil War.

Economic miracle

The Spanish Miracle (Desarrollo) was the name given to the Spanish economic boom between 1959 and 1973. During this period, Spain largely surpassed the per capita income that differentiates developed from underdeveloped countries and induced the development of a dominant middle class which was instrumental to the future establishment of democracy. The boom was bolstered by economic reforms promoted by the so-called technocrats, appointed by Franco, who put in place neo-liberal development policies from the IMF. The technocrats were a new breed of economists linked to Opus Dei, who replaced the old, prone to isolationism, Falangist guard.

The implementation of these policies took the form of development plans (planes de Desarrollo). Spain enjoyed the second highest growth rate in the world, just after Japan, and became the ninth largest economy in the world, just after Canada. Spain joined the industrialized world, leaving behind the poverty and endemic underdevelopment it had experienced since the loss of the Spanish Empire in the nineteenth century.

Although the economic growth produced noticeable improvements in Spanish living standards and the development of a middle class, Spain remained less economically advanced relative to the rest of Western Europe (with the exception of Portugal, Greece and Ireland). At the heyday of the Miracle, 1974, Spanish income per capita peaked at 79 percent of the Western European average, only to be reached again 25 years later, in 1999.

The 14 years of recovery led to an increase in (often unplanned) building on the periphery of the main Spanish cities to accommodate the new class of industrial workers brought by rural exodus, similar to the French banlieue. The icon of the Desarrollo was the SEAT 600, the first car for many Spanish working class families, produced by the Spanish factory SEAT or Sociedad Espa√Īola de Automotores.

Franco regime ends

The 1973 oil crisis brought Spain's economic growth to a halt. This caused a new wave of strikes (nominally illegal at the time). Franco's declining health gave more power to Admiral Luis Carrero Blanco, but he was assassinated by ETA in 1973. Carlos Arias Navarro took over as president, and tried to introduce some reforms to the decaying regime, but he struggled between the two factions of the regime, the b√ļnker (far-right) and the aperturists who promoted transition to democracy. But there was no way back to the old regime: Spain was not the same as in post-Civil War times and the model for the now wealthy Spaniards was the prosperous Western Europe, not the impoverished post-war Falangist Spain. Wealthy West Germany became a role model with which Spaniards identified themselves, as West Germans increasingly went on vacations to the Spanish beaches.

The size of the Spanish army and police was significantly smaller than pre-war times and the important Roman Catholic clergy were at the time deeply transformed, and sometimes deeply worried, by the reforms of the Vatican Council II.

In 1974 Franco fell ill, and Prince Juan Carlos took over as Head of State. Franco soon recovered, but one year later fell ill once again, and after a long illness, Franco died on November 20, 1975, at the age of 82‚ÄĒthe same date as the death of Jos√© Antonio Primo de Rivera, founder of the Falange. After Franco's death, the interim government decided to bury him at Santa Cruz del Valle de los Ca√≠dos, a colossal memorial to all the casualties of the Spanish Civil War.

Transition to democracy

Upon the death of General Franco, his personally-designated heir Prince Juan Carlos assumed the position of king and head of state. With the approval of the Spanish Constitution of 1978 and the arrival of democracy, some regions‚ÄĒBasque Country, Navarra‚ÄĒwere given complete financial autonomy, and many‚ÄĒBasque Country, Catalonia, Galicia and Andalusia‚ÄĒwere given some political autonomy, which was then soon extended to all Spanish regions, resulting in what is regarded as the most decentralized territorial organization in Western Europe. In the Basque Country, moderate Basque nationalism coexists with radical nationalism supportive of the terrorist group ETA.

From the time the constitution was passed in 1978 to September 2006 Spain has had five Presidentes del Gobierno (Prime Ministers): Adolfo Su√°rez Gonz√°lez (1977-1981) who won the election for the Uni√≥n de Centro Democr√°tico (UCD, now extinct), Leopoldo Calvo-Sotelo Bustelo (1981-1982) also for the UCD (under his presidency there was an attempted coup d'√©tat on February 23, 1981), Felipe Gonz√°lez M√°rquez (1982-1996) who won four consecutive elections heading the Partido Socialista Obrero Espa√Īol ticket (PSOE), during his administrations Spain joined NATO and European Union) and then Jos√© Mar√≠a Aznar L√≥pez (1996-2004) who won two consecutive elections for the Partido Popular (PP). Last in this list is current Presidente del Gobierno Jos√© Luis Rodr√≠guez Zapatero (2004-Incumbent) again for the PSOE. On January 1, 1999, Spain adopted the Euro as its national currency.

On March 11, 2004, a series of bombs exploded in commuter trains in Madrid, Spain. This act of terroris killed 191 people and wounded 1460 more, besides having a dramatic effect on the upcoming national elections. The bombings had an adverse effect on the then-ruling conservative party Partido Popular (PP) which all the polls were giving as a sure-fire winner of the elections, thus helping the election of Zapatero's Partido Socialista Obrero Espa√Īol (PSOE), on March 14 2004, with Jos√© Luis Rodr√≠guez Zapatero becoming the new prime minister of Spain. Among the main actions taken by the Zapatero administration were the withdrawal of Spanish troops from the Iraq war, reform of abortion law, and legalization same-sex marriages. Zapatero also presided over the Spanish Parliament's approval of the new (and controversial) Statute of Autonomy of Catalonia.

On June 19 2014, King Juan Carlos I abdicated in favour of his son, who became Felipe VI.

Government and politics

Constitutional structure

Spain is a constitutional monarchy, with a hereditary monarch, who is chief of state, and a bicameral parliament, the Cortes Generales. The executive branch consists of a Council of Ministers presided over by the President of Government (comparable to a prime minister), proposed by the monarch and elected by the National Assembly following legislative elections.

The legislative branch is made up of the Congress of Deputies (Congreso de los Diputados) with 350 members, elected by popular vote on block lists by proportional representation to serve four-year terms, and a Senate or Senado with 259 seats of which 208 are directly elected by popular vote and the other 51 appointed by the regional legislatures to also serve four-year terms. Suffrage is universal to all aged 18 years and over.

The Spanish judiciary has professional judges and magistrates and consists of different courts, the highest ranking court being the Supreme Court. The role of the judiciary is governed by the General Council of the Judiciary Power whose chairperson is also the chairperson of the Supreme Court. Spain uses a civil law system, with regional applications, and accepts compulsory International Court of Justice (CJ) jurisdiction with reservations.

Spain was, in 2007, what is called a State of Autonomies, formally unitary but, in fact, functioning as a highly decentralized Federation of Autonomous Communities, each one with slightly different levels of self-government. The pattern of asymmetrical devolution, as used in Spain, has been described as a co-constitutionalism and the devolution process adopted by the United Kingdom since 1997 shares traits with it.

Spain was regarded as the most decentralized State in Europe in 2007, with all of its different territories managing locally their health and education systems, and with some other territories (the Basque Country and Navarre) even managing their public finances without involvement of the Spanish central government, and in the case of Catalonia and the Basque Country, equipped with their own, fully operative and completely autonomous, police corps.

Administrative divisions

Spain is divided into 17 autonomous communities: Andalusia, Arag√≥n, Asturias, Balearic Islands, Canary Islands, Cantabria, Castilla-La Mancha, Castilla y Le√≥n, Catalonia, Valencia, Extremadura, Galicia, La Rioja, Madrid, Murcia, Navarre and Basque Country. There are five places of sovereignty near Morocco: Ceuta and Melilla are administered as autonomous cities, with more powers than cities but fewer than autonomous communities; Islas Chafarinas, Pe√Ī√≥n de Alhucemas, and Pe√Ī√≥n de V√©lez de la Gomera are under direct Spanish administrations.

Basque separatists

The Government of Spain has been involved in a long-running campaign against Basque Fatherland and Liberty (ETA), a terrorist organization founded in 1959 in opposition to Franco and dedicated to promoting Basque independence through violence. They consider themselves a guerrilla organization while they are actually listed as a terrorist organization by both the European Union and the United States. Although the current nationalist-led Basque Autonomous government does not endorse any kind of violence, their different approaches as to how to terminate ETA and their different approaches to the separatist movement are a source of tension between the central and Basque governments.

Initially ETA targeted primarily Spanish security forces, military personnel and Spanish Government officials. As the security forces and prominent politicians improved their own security, ETA increasingly focused its attacks on the tourist seasons (scaring tourists was seen as a way of putting pressure on the government, given the sector's importance to the economy, although no tourists were injured) and local government officials in the Basque Country. The group carried out numerous bombings against Spanish Government facilities and economic targets, including a car bomb assassination attempt on then-opposition leader Aznar in 1995, in which his armored car was destroyed but he was unhurt. The Spanish Government attributes over 800 deaths to ETA during its campaign of rebellion.

On May 17, 2005, all the parties in the Congress of Deputies, except the PP, passed the Central Government's motion giving approval to the beginning of peace talks with ETA, without making political concessions and with the requirement that it give up its weapons. PSOE, CiU, ERC, PNV, IU-ICV, CC and the mixed group‚ÄĒBNG, CHA, EA y NB‚ÄĒsupported it with a total of 192 votes, while the 147 PP parliamentarians objected. ETA declared a "permanent cease-fire" that came into force on March 24, 2006. In the years leading up to the permanent cease-fire, the government had had more success in controlling ETA, due in part to increased security cooperation with French authorities.

Territorial disputes

Spain has called for the return of Gibraltar, a British possession on its southern coast. It was conquered during the War of the Spanish Succession in 1704 and was ceded to Britain in perpetuity in the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht. An overwhelming majority of Gibraltar's 30,000 inhabitants want to remain British, as they have repeatedly proven in referenda on the issue. The UN resolutions (2231 (XXI) and 2353 (XXII)) call on the UK and Spain to reach an agreement. According to Spain, these resolutions overrule the Treaty of Utrecht. However, Article 103 of the UN Charter makes clear that the right of self-determination of the people of Gibraltar is the paramount and overriding principle. There is also dispute regarding the demarcation line. Gibraltar is officially a non-self-governing territory or colony according to the UN.

Morocco claims the Spanish cities of Ceuta and Melilla and the Vélez, Alhucemas, Chafarinas, and Perejil islands, all on the Northern coast of Africa. Morocco points out that those territories were obtained when Morocco could not do anything to prevent it and has never signed treaties ceding them. Morocco, as a nation, didn't exist in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries when these places became Spanish possessions. Spain claims that these territories are integral parts of Spain and have been Spanish or linked to Spain since before the Islamic invasion of Spain in 711.

Portugal does not recognize Spain's sovereignty over the territory of Olivenza. The Portuguese claim that the Treaty of Vienna (1815), to which Spain was a signatory, stipulated return of the territory to Portugal. Spain alleges that the Treaty of Vienna left the provisions of the Treaty of Badajoz intact.

Foreign relations of Spain

After the return of democracy since 1975, Spain's foreign policy priorities were to break out of the diplomatic isolation of the Franco years and expand diplomatic relations, enter the European Community, and define security relations with the West. As a member of NATO since 1982, Spain has established itself as a major participant in multilateral international security activities. Spain's EU membership represents an important part of its foreign policy. Even on many international issues beyond western Europe, Spain prefers to coordinate its efforts with its EU partners through the European political cooperation mechanisms.

With the normalization of diplomatic relations with North Korea in 2001, Spain completed the process of universalizing its diplomatic relations. Spain has maintained its special identification with Latin America. Its policy emphasizes the concept of an Iberoamerican community, essentially the renewal of the historically liberal concept of hispanoamericanismo (or hispanism, as it is often referred to in English), which has sought to link the Iberian peninsula with Latin America through language, commerce, history and culture. Spain has been an example of transition from dictatorship to democracy.

Military

The armed forces of Spain consist of the Army, Navy and Air Force, a modern military force. The armed forces are active members of NATO, the Eurocorps, and the European Union Battlegroups. The Commander-in-Chief is the King of Spain.

The Spanish Army has existed continuously since the reign of King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella in the late fifteenth century. The oldest and largest of the three services, its mission was the defense of peninsular Spain, the Balearic Islands, the Canary Islands, Melilla, Ceuta and the Spanish islands and rocks off the northern coast of Africa. The army was to be increased to about 86,000 troops (26,000 officers and 60,000 soldiers) by the end of 2007. Before 2001 mandatory military service was in use. As of 2007, the Spanish Army has been a fully professionalized force. In case of war or siege state, an additional force of 80,000 Civil Guards comes under the Ministry of Defence command.

The Spanish Navy (Armada) is considerable, ranking second in total tonnage, after the Royal Navy, among European NATO nations. Its strength has been reduced by 10,000 to 47,300 personnel, including Marines, as of 1987. Of this number, about 34,000 were conscripts.

Although Spanish Military Aviation started with a balloon force in 1896, April 10, 1910, is the date when the Spanish military aviation was formally formed by means of a Royal Decree. On November 5, 1913, during the war with Morocco, a Spanish expeditionary squadron became the first organized military air unit to see combat during the first organized bombing in history. The Ejército del Aire (EdA) was not formed until October 7, 1939, at the end of the Spanish Civil War, as a successor to the Nationalist and Republican Air Forces. During World War II one air section, the Division Azul, a Spanish volunteer group fought alongside the Axis Powers on the Eastern Front.

Economy

In 1975, when Franco died, government intervention in the economy was widespread. The government fixed the prices of basic products like bread and sugar, and fixed interest rates, large public firms controlled all sectors regarded as strategic (telephone, tobacco, petrol), shops had fixed opening and closing times (although this too existed, in other European countries, such as Germany). All these rigidities and more were made obvious by the 1973 oil crisis, which terminated the previous expansion cycle and unleashed a roughly ten years period of severe industrial crisis (1975-1985). This blow stressed the need to modernize the economy and join the European Community.

Spain's accession to the European Community, later the European Union (EU), in January 1986, encouraged the country to open its economy, modernize its industrial base and revise economic legislation. As a result, Spain greatly improved infrastructure, increased GDP growth, reduced the public debt to GDP ratio, reduced unemployment from 23 percent to 10 percent, and reduced inflation to under 3 percent. The Spanish economy boomed from 1986 to 1990, averaging five percent annual growth. After a European-wide recession in the early 1990s, the Spanish economy resumed moderate growth starting in 1994. Spain's mixed capitalist economy supports a GDP that on a per capita basis is 80 percent that of the four leading West European economies.

The center-right government of former President José María Aznar gained admission to the group of countries launching the euro on January 1, 1999. The Aznar administration continued to advocate liberalization, privatization, and deregulation of the economy and introduced some tax reforms to that end. Unemployment fell steadily under the Aznar administration but remained around eight percent. Growth averaged three percent annually during 2003-2006.

The Socialist president, Rodriguez Zapatero, planned to reduce government intervention in business, combat tax fraud, and support innovation, research and development, but also intended to reintroduce labor market regulations that had been done away with by the Aznar government.

Exports totaled $216.5-billion in 2006. Export commodities included machinery, motor vehicles; foodstuffs, pharmaceuticals, medicines, and other consumer goods. Export partners included France 18.9 percent, Germany 11 percent, Portugal 8.9 percent, Italy 8.6 percent, UK 7.8 percent, and the US 4.5 percent. Imports totaled $317.1-billion in 2006. Import commodities included machinery and equipment, fuels, chemicals, semifinished goods, foodstuffs, consumer goods, and measuring and medical control instruments. Import partners included Germany 14.7 percent, France 13.2 percent, Italy 8.1 percent, UK 5 percent, Netherlands 4.8 percent, and China 4.8 percent.

The GDP per capita was $26,320 in 2005, a rank of 25 out of 194 countries. The unemployment rate was 8.1 percent in 2006, and 9.8 percent of the population existed below the poverty line in 2005.

The Spanish economy had benefited greatly from the global real estate boom, with construction representing an astonishing 16 percent of GDP and 12 percent of employment in its final year. However, the downside of the defunct real estate boom was a corresponding rise in the levels of personal debt; as prospective homeowners had struggled to meet asking prices, the average level of household debt tripled in less than a decade. The property bubble that had begun building from 1997, fed by historically low interest rates and an immense surge in immigration, imploded in 2008, leading to a rapidly weakening economy and soaring unemployment. By the end of 2010 unemployment had reached 20.33 (over 28 percent in Andalucia and the Canaries).[10]

Demographics

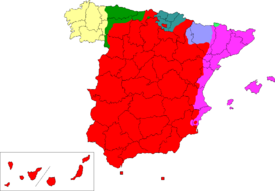

| ‚Ėą‚Ėą¬†Castilian (Spanish) ‚Ėą‚Ėą¬†Catalan, co-official ‚Ėą‚Ėą¬†Basque, co-official ‚Ėą‚Ėą¬†Galician, co-official | ‚Ėą‚Ėą¬†Asturian, unofficial ‚Ėą‚Ėą¬†Aragonese, unofficial ‚Ėą‚Ėą¬†Aranese, co-official (dialect of Occitan) |

Population

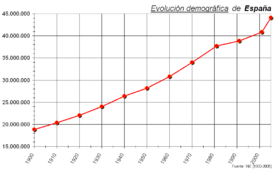

The population of Spain doubled during the twentieth century, reaching 46 million people at the beginning of the twenty-first century. The birthrate increased spectacularly in the 1960s and early 1970s, but plunged in the 1980s. A new population increase began with many Spanish who had emigrated during the 1970s returned and, with large numbers of foreign immigrants, mostly from Latin America, Eastern Europe, Maghreb, and sub-Saharan Africa.

There was also large-scale internal migration from the rural interior to the industrial cities during the 1960s and 1970s. No fewer than 11 of Spain's 50 provinces saw a decline in population over the century. Spain's population density, at 220 per square mile (87.8/km²) is lower than that of most Western European countries and its distribution along the country is unequal. With the exception of the region surrounding the capital, Madrid, the most populated areas lie around the coast.

Ethnicity

Spain itself consists of various regional nationalities including the Castilians (who most strongly identify with the Spanish identity), the Catalans, Valencians and Balearics (speakers of a distinct yet related Romance language in eastern Spain), the Basques (a distinct people inhabiting the Basque country), and the Galicians, who speak a language which is close to Portuguese. Regional diversity is important to many Spaniards and some regions (other than the ones associated with the different nationalities) also have strong local identities and dialects, such as Asturias, Aragon, the Canary Islands, and Andalusia. The Spanish Constitution of 1978, in its second article, recognizes historic entities "nationalities" (a carefully chosen word in order to avoid the more politically loaded "nations") and regions, inside the unity of the Spanish nation.

Since the sixteenth century, the most famous minority group in the country (though not the biggest in number) have been the Gitanos, a Roma group.

Spain harbors a number of black African-blooded people‚ÄĒwho are descendants of populations from former colonies (especially Equatorial Guinea) and, immigrants from several Sub-Saharan and Caribbean countries. There are also sizable numbers of Asian-Spaniards, most of whom are from Chinese, Filipino, Middle Eastern, Pakistani and Indian origins; Spaniards of Latin American descent are also sizable as well.

The important Jewish population of Spain was either expelled or forced to convert in 1492 under the Alhambra Decree, with the dawn of the Spanish Inquisition. After the nineteenth century, some Jews have established themselves in Spain as a result of migration from former Spanish Morocco, escape from Nazi repression, and immigration from Argentina. The Spanish law allows Sephardi Jews to claim Spanish citizenship.

Religion