Diego Velázquez

| Diego Velázquez | |

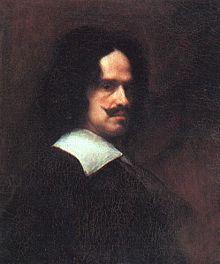

Self portrait of Diego Velázquez, painted around 1643. Uffizi gallery, Florence, Italy | |

| Birth name | Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez |

| Born | June 6, 1599 Seville, Spain |

| Died | August 6, 1660 (aged 61) Madrid, Spain |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Field | Painting |

| Famous works | Las Meninas (1656), La Venus del espejo (The Rokeby Venus) (1644-1648) La Rendición de Breda, (The Surrender of Breda) (1634-1635) |

Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez (June 6, 1599 – August 6, 1660), commonly referred to as Diego Velázquez, was a Spanish painter, the leading artist in the court of King Philip IV. He was an individualistic artist of the contemporary Baroque period, important as a portrait artist. He lived in Italy for a year and a half from 1629 to 1631 with the purpose of traveling and studying works of art. In 1649 he traveled to Italy again. In addition to numerous renditions of scenes of historical and cultural significance, he created scores of portraits of the Spanish royal family, other notable European figures, and commoners, culminating in the production of his masterpiece, Las Meninas (1656).

From the first quarter of the seventeenth century, Velázquez's artwork was a model for the realist and impressionist painters, in particular Édouard Manet. Since that time, more modern artists, including Spain's Pablo Picasso and Salvador Dalí, as well as the Anglo-Irish painter Francis Bacon have paid tribute to Velázquez by recreating several of his most famous works. Centuries before film and photography, an artist such as Velázquez also played an important role in preserving for posterity through his painting images that would otherwise have been lost to the world. As life in seventeenth century Spain is reconstructed, alongside written records, art such as produced by Velazquez aids the process of historical research.

Early life

Born in Seville, Andalusia, Spain early on June 6, 1599, and baptized on June 6, Velázquez was the son of Juan Rodríguez de Silva (born João Rodrigues da Silva), a lawyer of Portuguese Jewish descent (son of Diogo da Silva and wife Maria Rodrigues, Portuguese Jews), and Jerónima Velázquez, a member of hidalgo class, an order of minor aristocracy (it was a Spanish custom, in order to maintain a legacy of maternal inheritance, for the eldest male to adopt the name of his mother). Recent archival investigations carried out by Mendez, Ingram and others not only reject his aristocratic origins but have brought to light that he belonged to the Jewish converso lineage.[1] He was educated by his parents to fear God and, intended for a learned profession, received good training in languages and philosophy. But he showed an early gift for art; consequently, he began to study under Francisco de Herrera, a vigorous painter who disregarded the Italian influence of the early Seville school. Velázquez remained with him for one year. It was probably from Herrera that he learned to use brushes with long bristles.

After leaving Herrera's studio when he was 12 years old, Velázquez began to serve as an apprentice under Francisco Pacheco, an artist and teacher in Seville. Though considered a generally dull, commonplace painter, Pacheco sometimes expressed a simple, direct realism in contradiction to the style of Raphael that he was taught. Velázquez remained in Pacheco's school for five years, studying proportion and perspective and witnessing the trends in the literary and artistic circles of Seville.

To Madrid (early period)

By the early 1620s his position and reputation were assured in Seville; Velázquez's wife, married in 1618, Juana Pacheco (June 1, 1602-August 10, 1660) (daughter of Francisco Pacheco), in these years bore him two daughters—his only known family. The younger, Ignacia de Silva Velázquez y Pacheco, died in infancy, while the elder, Francisca de Silva Velázquez y Pacheco (1619-1658), in due time in August 21, 1633 married Juan Bautista Martínez del Mazo, a painter, at the Church of Santiago in Madrid. Velázquez produced other notable works in this time. Sacred subjects are depicted in Adoración de los Reyes (1619, English: The Adoration of the Magi), and Jesús y los peregrinos de Emaús (1626, English: Christ and the Pilgrims of Emmaus), both of which begin to express his more pointed and careful realism.

Madrid and Philip IV

Velázquez went to Madrid in the first half of April 1622, with letters of introduction to Don Juan de Fonseca, himself from Seville, who was chaplain to the King. At the request of Pacheco, Velázquez painted the portrait of the famous poet Luis de Góngora y Argote. Velázquez painted Góngora crowned with a laurel wreath, but at some unknown later date painted over it. It is possible that Velázquez stopped in Toledo on his way from Seville, on the advice of Pacheco, or back from Madrid on that of Góngora, a great admirer of El Greco, having composed a poem on the occasion of his death.

In December 1622, Rodrigo de Villandrando, the King's favorite court painter, died. Don Juan de Fonseca conveyed to Velázquez the command to come to the Court from the Count-Duke of Olivares, the powerful minister of Philip IV. He was offered 50 ducats (175 g of gold—worth about €2000 in 2005) to defray his expenses, and he was accompanied by his father-in-law. Fonseca lodged the young painter at his own home and sat for a portrait himself, which, when completed, was conveyed to the Royal palace. A portrait of the King was commissioned. On August 16, 1623, the King sat for Velázquez. Complete in one day the portrait was likely to have been no more than a head sketch, but both the King and Olivares were pleased. Olivares commanded Velázquez to move his home to Madrid, promising that no other painter would ever paint the King's portrait and all other portraits of the King would be withdrawn from circulation. In the following year, 1624, he received 300 ducats from the king to pay the cost of moving his family to Madrid, which became his home for the remainder of his life.

Through an equestrian portrait of the king, painted in 1623, Velázquez secured admission to the royal service with a salary of 20 ducats per month, besides medical attendance, lodgings and payment for the pictures he might paint. The portrait was exhibited on the steps of San Felipe and was received with enthusiasm. It is now lost. The Museo del Prado, however, has two of Velázquez's portraits of the king (nos. 1070 and 1071) in which the severity of the Seville period has disappeared and the tones are more delicate. The modeling is firm, recalling that of Antonio Mor, the Netherlandish portrait painter of Philip II, who exercised a considerable influence on the Spanish school. In the same year the Prince of Wales (afterwards Charles I) arrived at the court of Spain. Records indicate that he sat for Velázquez, but the picture is now lost.

In September 1628 Peter Paul Rubens came to Madrid as an emissary from the Infanta Isabella, and Velázquez kept his company among the Titians at the Escorial. Rubens was then at the height of his powers. The seven months of the diplomatic mission showed Rubens' brilliance as painter and courtier. Rubens had a high opinion of Velázquez, but he effected no great change in his painting. He reinforced Velázquez's desire to see Italy and the works of the great Italian masters.

In 1627, Philip set a competition for the best painters of Spain the subject of the expulsion of the Moors. Velázquez won. His picture was destroyed in a fire at the palace in 1734. Recorded descriptions of it say that it depicted Philip III pointing with his baton to a crowd of men and women driven off under charge of soldiers, while the female personification of Spain sits in calm repose. Velázquez was appointed gentleman usher as reward. Later he also received a daily allowance of 12 réis, the same amount allotted to the court barbers, and 90 ducats a year for dress. Five years after he painted it, as an extra payment he received 100 ducats for the picture of Bacchus (The Feast of Bacchus), painted in 1629. The spirit and aim of this work are better understood from its Spanish name, Los borrachos or Los bebedores (the tipplers), who are paying mock homage to a half-naked ivy-crowned young man seated on a wine barrel. The painting is firm and solid, and the light and shade are more deftly handled than in former works. Altogether, this production may be taken as the most advanced example of the first style of Velázquez.

Italian period

In 1629 he went to live in Italy for a year and a half. Though his first Italian visit is recognized as a crucial chapter in the development of Velázquez's style - and in the history of Spanish Royal Patronage, since Philip IV sponsored his trip - we know rather little about the details and specifics: what the painter saw, whom he met, how he was perceived and what innovations he hoped to introduce into his painting. It is canonical to divide the artistic career of Velázquez by his two visits to Italy, with his second grouping of works following the first visit and his third grouping following the second visit. This somewhat arbitrary division may be accepted though it will not always apply, because, as is usual in the case of many painters, his styles at times overlap each other. Velázquez rarely signed his pictures, and the royal archives give the dates of only his most important works. Internal evidence and history pertaining to his portraits supply the rest to a certain extent.

Return to Madrid (middle period)

Velázquez then painted the first of many portraits of the young prince and heir to the Spanish throne, Don Baltasar Carlos, looking dignified and lordly even in his childhood, in the dress of a field marshal on his prancing steed. The scene is in the riding school of the palace, the king and queen looking on from a balcony, while Olivares attends as master of the horse to the prince. Don Baltasar died in 1646 at the age of seventeen, so, judging by his age in the portrait, it must have been painted in about 1641.

The powerful minister Olivares was the early and constant patron of the painter. His impassive, saturnine face is familiar to us from the many portraits painted by Velázquez. Two are notable; one is a full-length, stately and dignified, in which he wears the green cross of the order of Alcantara and holds a wand, the badge of his office as master of the horse, the other, a great equestrian portrait in which he is flatteringly represented as a field marshal during action. In these portraits, Velázquez has well repaid the debt of gratitude that he owed to his first patron, whom Velázquez stood by during Olivares's fall from power, thus exposing himself to the great risk of the anger of the jealous Philip. The king, however, showed no sign of malice towards his favorite painter.

The sculptor Montafles modeled a statue of one of Velázquez's equestrian portraits of the king, painted in 1636, which was cast in bronze by the Florentine sculptor Tacca and which now stands in the Plaza de Oriente at Madrid. The original of this portrait no longer exists, but several others do. Velázquez, in this and in all his portraits of the king, depicts Philip wearing the golilla, a stiff linen collar projecting at right angles from the neck. It was invented by the king, who was so proud of it that he celebrated it by a festival followed by a procession to the church to thank God for the blessing. Thus, the golilla was the height of fashion, and appeared in most of the male portraits of the period.

Velázquez was in constant and close attendance on Philip, accompanying him in his journeys to Aragon in 1642 and 1644, and was doubtless present with him when he entered Lerida as a conqueror. It was then that he painted a great equestrian portrait in which the king is represented as a great commander leading his troops—a role which Philip never played except in pageantry. All is full of animation except the stolid face of the king. It hangs as a pendant to the great Olivares portrait—fit rivals of the neighboring Charles V by Titian, which inspired Velázquez to excel himself, and both remarkable for their silvery tone and their feeling of open air.

Portraiture

Besides the 40 portraits of Philip by Velázquez, he painted portraits of other members of the royal family: Philip's first wife, Isabella of Bourbon, and her children, especially her eldest son, Don Baltasar Carlos, of whom there is a beautiful full-length in a private room at Buckingham Palace. Cavaliers, soldiers, churchmen, and the prominent poet Francisco de Quevedo (now at Apsley House), sat for Velázquez.

One wonders who the beautiful woman can be who adorns the Wallace collection, a brunette so unlike the usual fair-haired female sitters to Velázquez. This picture is one of the ornaments of the Wallace collection. However, if few ladies of the court of Philip have been depicted, Velázquez painted several of his buffoons and dwarfs. Velázquez appears to represent them with respect and sympathetically, as in El Primo (1644, English: The Favorite), whose intelligent face and huge folio with ink-bottle and pen by his side show him to be a wiser and better-educated man than many of the gallants of the court. Pablo de Valladolid (1635, English: Paul of Valladolid), a buffoon evidently acting a part, and El Bobo de Coria (1639, English: The Buffoon of Coria) belong to this middle period.

The greatest of the religious paintings by Velázquez also belongs to this middle period, the Cristo Crucificado (1632, English: Christ on the Cross). It is a work of tremendous originality, depicting Christ immediately after death. The Savior's head hangs on his breast and a mass of dark tangled hair conceals part of the face. The figure stands alone. The picture was lengthened to suit its place in an oratory, but this addition has since been removed. Some believe that the man in this painting is his uncle.

Velázquez's son-in-law Juan Bautista Martinez del Mazo had succeeded him as usher in 1634, and Mazo himself had received a steady promotion in the royal household. Mazo received a pension of 500 ducats in 1640, increased to 700 in 1648, for portraits painted and to be painted, and was appointed inspector of works in the palace in 1647.

Philip now entrusted Velázquez with carrying out a design on which he had long set his heart: the founding of an academy of art in Spain. Rich in pictures, Spain was weak in statuary, and Velázquez was commissioned once again to proceed to Italy to make purchases.

Second visit to Italy

Accompanied by his manservant Pareja, whom he trained in painting, Velázquez sailed from Málaga in 1649, landing at Genoa, and proceeded from Milan to Venice, buying paintings of Titian, Tintoretto and Veronese as he went. At Modena he was received with much favor by the duke, and here he painted the portrait of the duke at the Modena gallery and two portraits that now adorn the Dresden gallery, for these paintings came from the Modena sale of 1746.

Those works presage the advent of the painter's third and latest manner, a noble example of which is the great portrait of Pope Innocent X in the Doria Pamphilj Gallery in Rome, where Velázquez now proceeded. There he was received with marked favor by the Pope, who presented him with a medal and golden chain. Velázquez took a copy of the portrait—which Sir Joshua Reynolds thought was the finest picture in Rome—with him to Spain. Several copies of it exist in different galleries, some of them possibly studies for the original or replicas painted for Philip. Velázquez, in this work, had now reached the manera abreviada, a term coined by contemporary Spaniards for this bolder, sharper style. The portrait shows such ruthlessness in Innocent's expression that some in the Vatican feared that Velázquez would meet with the Pope's displeasure, but Innocent was well pleased with the work, hanging it in his official visitor's waiting room.

In 1650 in Rome Velázquez also painted a portrait of his servant, Juan de Pareja, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. This portrait procured his election into the Academy of St. Luke. Purportedly Velázquez created this portrait as a warm-up of his skills before his portrait of the Pope. It captures in great detail Pareja's countenance and his somewhat worn and patched clothing with an impressive economy of brushwork; it is one of his best known pieces of portraiture.

Return to Spain (later period)

King Philip wished that Velázquez return to Spain; accordingly, after a visit to Naples, where he saw his old friend José Ribera, he returned to Spain via Barcelona in 1651, taking with him many pictures and 300 pieces of statuary, which afterwards were arranged and cataloged for the king. Undraped sculpture was, however, abhorrent to the Spanish Church, and after Philip's death these works gradually disappeared. Isabella of Bourbon had died in 1644, and the king had married Marie-Anne of Austria, whom Velázquez now painted in many attitudes. He was specially chosen by the king to fill the high office of aposentador mayor, which imposed on him the duty of looking after the quarters occupied by the court—a responsible function which was no sinecure and one which interfered with the exercise of his art. Yet far from indicating any decline, his works of this period are amongst the highest examples of his style.

Las Meninas

One of the infantas, Margarita, the eldest daughter of the new Queen, appears to be subject of Las Meninas (1656, English: The Maids of Honor), Velázquez's magnum opus. However, in looking at the various viewpoints of the painting it is unclear as to who, or what is the true subject. Is it the royal daughter, or perhaps the painter himself? The answer may lie in the image on the back wall, depicting the King and Queen. Is this image a mirror, in which case the King and Queen are standing where we stand? Are they the subject of Valesquez's work? Or is the work simply a court painting? Much is still in speculation about the true subject of this masterpiece, and many of the questions that we ask may never be truly answered.

Created four years before his death, it is a staple of the European Baroque period of art. An apotheosis of the work has been effected since its creation; Luca Giordano, a contemporary Italian painter, referred to it as the "theology of painting," and the eighteenth century the Englishman Thomas Lawrence cited it as the "philosophy of art," so decidedly capable of producing its desired effect. That effect has been variously interpreted; Dale Brown points out an interpretation that, in inserting within the work a faded portrait of the king and queen hanging on the back wall, Velázquez has ingeniously prognosticated the fall of the Spanish empire that was to gain momentum following his death. Another interpretation is that the portrait is in fact a mirror, and that the painting itself is in the perspective of the King and Queen, hence their reflection can be seen in the mirror on the back wall.

It is said the king painted the honorary Cruz Roja (Red Cross) of the Orden de Santiago (Order of Santiago) on the breast of the painter as it appears today on the canvas. However, Velázquez did not receive this honor of knighthood until three years after execution of this painting. Even the King of Spain could not make his favorite a belted knight without the consent of the commission established to inquire into the purity of his lineage. This aim of these inquiries would be to prevent the appointment to positions of anyone found to have even a taint of heresy in their lineage—that is, a trace of Jewish or Moorish blood or contamination by trade or commerce in either side of the family for many generations. The records of this commission have been found among the archives of the Order of Santiago. Velázquez was awarded the honor in 1659. His occupation as plebeian and tradesman was justified because, as painter to the king, he was evidently not involved in the practice of "selling" pictures.

In his 1966 book The Order of Things, the philosopher Michel Foucault devotes the opening chapter to a detailed analysis of Las Meninas. He describes the ways in which the painting problematizes issues of representation through its use of mirrors, screens, and the subsequent oscillations that occur between the image's interior, surface, and exterior. In his novel, The Dying Animal, Philip Roth uses Las Meninas as a metaphor for the distracted attraction of courtship.

Final years

Had it not been for this royal appointment, which enabled Velázquez to escape the censorship of the Inquisition, he would not have been able to release his La Venus del espejo (c. 1644-1648, English: Venus at her Mirror) also known as The Rokeby Venus. It is the only surviving female nude by Velázquez.

There were essentially only two patrons of art in Spain—the Church and the art-loving king and court. Bartolome Esteban Murillo was the artist favored by the church, while Velázquez was patronized by the crown. One difference, however, deserves to be noted. Murillo, who toiled for a rich and powerful church, left little means to pay for his burial, while Velázquez lived and died in the enjoyment of good salaries and pensions.

One of his final works was Las hilanderas (The Spinners), painted circa 1657, representing the interior of the royal tapestry works. It is full of light, air and movement, featuring vibrant colors and careful handling. Anton Raphael Mengs said this work seemed to have been painted not by the hand but by the pure force of will. It displays a concentration of all the art-knowledge Velázquez had gathered during his long artistic career of more than 40 years. The scheme is simple—a confluence of varied and blended red, bluish-green, grey and black.

Velazquez' final portraits of the royal children are among his finest works. These include the Infanta Margarita in blue dress and his only surviving portrait of the sickly Prince Felipe Prospero. The latter is remarkable for its combination of the sweet features of the child prince and his dog with a subtle sense of gloom. As in all of the artist's late paintings, the handling of the colors is extraordinarily fluid and vibrant.

In 1660 a peace treaty between France and Spain was consummated by the marriage of Maria Theresa with Louis XIV, and the ceremony took place on the Island of Pheasants, a small swampy island in the Bidassoa. Velázquez was charged with the decoration of the Spanish pavilion and with the entire scenic display. He attracted much attention from the nobility of his bearing and the splendor of his costume. On June 26 he returned to Madrid, and on July 31 he was stricken with fever. Feeling his end approaching, he signed his will, appointing as his sole executors his wife and his firm friend named Fuensalida, keeper of the royal records. He died on August 6, 1660. He was buried in the Fuensalida vault of the church of San Juan Bautista, and within eight days his wife Juana was buried beside him. Unfortunately, this church was destroyed by the French in 1811, so his place of interment is now unknown. There was much difficulty in adjusting the tangled accounts outstanding between Velázquez and the treasury, and it was not until 1666, after the death of King Philip, that they were finally settled.

Legacy

Until the nineteenth century, little was known outside of Spain of Velázquez's work. His paintings mostly escaped being stolen by the French marshals during the Peninsular War. In 1828 Sir David Wilkie wrote from Madrid that he felt himself in the presence of a new power in art as he looked at the works of Velázquez, and at the same time found a wonderful affinity between this artist and the British school of portrait painters, especially Henry Raeburn. He was struck by the modern impression pervading Velázquez's work in both landscape and portraiture.

His technique and individuality have earned Velázquez a prominent position in the annals of European art, and he is often considered a father of the Spanish school of art. Although acquainted with all the Italian schools and a friend of the foremost painters of his day, he was strong enough to withstand external influences and work out for himself the development of his own nature and his own principles of art.

Velázquez is often cited as a key influence on the art of Édouard Manet, who is often cited as the bridge between realism and Impressionism. Calling Velázquez the "painter of painters," Manet admired Velázquez's use of vivid brushwork in the midst of the Baroque academic style of his contemporaries and built upon Velázquez's motifs in his own art.

Modern recreations of classics

The importance of Velázquez's art is evident in considering the respect with which twentieth century painters regard his work. Pablo Picasso presented the most durable homage to Velázquez in 1957 when he recreated Las Meninas in his characteristically cubist form. While Picasso was worried that if he copied Velázquez's painting, it would be seen only as a copy and not as any sort of unique representation, he proceeded to do so, and the enormous work—the largest he had produced since Guernica in 1937—earned a position of relevance in the Spanish canon of art. Picasso retained the general form and positioning of the original in the framework of his avant-garde cubist style.

Salvador Dalí, as with Picasso in anticipation of the tercentennial of Velázquez's death, created in 1958 a work entitled Velázquez Painting the Infanta Margarita With the Lights and Shadows of His Own Glory. The color scheme shows Dalí's serious tribute to Velázquez; the work also functioned, as in Picasso's case, as a vehicle for the presentation of newer theories in art and thought—nuclear mysticism, in Dalí's case.

The Anglo-Irish painter Francis Bacon found Velázquez's portrait of Pope Innocent X to be one of the greatest portraits ever made. He created several expressionist variations of this piece in the 1950s; however, Bacon's paintings presented a more gruesome image of the pope, who had now been dead for centuries. One such famous variation, entitled Figure with Meat (1954), shows the pope between two halves of a bisected cow.

Descendants

Velazquez' daughter was an ancestress of Marquises de Monteleon, including Enriquetta Casado who in 1746 married Heinrich VI, Count Reuss zu Köstritz and had large number of descendants among German aristocracy, among them Prince Bernhard of the Netherlands, father of Queen Beatrix of the Netherlands.

Selected works

- The Lunch (c. 1617) - Oil on canvas, 108 x 102 cm, Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg

- Old Woman Frying Eggs (c. 1618) - Oil on canvas, 105 × 119 cm, National Gallery, Edinburgh

- Christ in the House of Martha and Mary (1618) - Oil on canvas, 63 x 103.5 cm, National Gallery, London

- The Adoration of the Magi (1619) - Oil on canvas, 203 × 125 cm, Museo del Prado, Madrid

- The Waterseller of Seville (c. 1620) - Oil on canvas, 105 × 80 cm, Apsley House, London

- Portrait of Mother Jeronima de la Fuente (1620) - Oil on canvas, 79 x 51 cm, Museo del Prado, Madrid[2][3]

- Imposición de la casulla a San Ildefonso (1623) - Oil on canvas, 165 × 115 cm, Museo de Bellas Artes, Sevilla

- Portrait of Count Duke of Olivares (1624) - Oil on canvas, 202 x 107 cm, São Paulo Museum of Art, Sao Paulo

- El Triunfo de Baco (Los borrachos) (1628 - 1629) - Oil on canvas, 165 x 225 cm, Museo del Prado, Madrid

- La reina Isabel de Borbón a caballo (1629) - Oil on canvas, 301 x 314 cm, Museo del Prado, Madrid

- Apolo en la Fragua de Vulcano (1630) - Oil on canvas, 223 x 290 cm, Museo del Prado, Madrid

- The Lady with a Fan (c. 1638 - 1639) - Oil on wood, 69 x 51 cm, The Wallace Collection, London[2][4][5]

- Cristo crucificado (1631) - Oil on canvas, 248 x 169 cm, Museo del Prado, Madrid

- Equestrian portrait of Duke de Olivares (1634) - Oil on canvas, 313 x 239 cm, Museo del Prado, Madrid

- Surrender of Breda (1633 - 1635) - Oil on canvas, 307 × 367 cm, Museo del Prado, Madrid

- Portrait of Duke de Olivares (1635) - Oil on canvas, 67 × 54.5 cm, Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg

- Menipo (1639 - 1640) - Oil on canvas, 179 × 94 cm, Museo del Prado, Madrid

- Esopo (1639 - 1640) - Oil on canvas, 179 × 94 cm, Museo del Prado, Madrid

- Mars Resting (1640) - Oil on canvas, 179 × 95 cm, Museo del Prado, Madrid

- The Rokeby Venus (La Venus del espejo c. 1648-1651) - Oil on canvas, 122 × 177 cm, National Gallery, London

- Portrait of Innocent X (c. 1650) - Oil on canvas, 141 x 119 cm, Galleria Doria Pamphilj, Rome

- Portrait of Juan de Pareja (1650) - Oil on canvas, 81.3 x 69.9 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

- Las Meninas (1656) - Oil on canvas, 318 × 276 cm, Museo del Prado, Madrid

- Las Hilanderas (The Fable of Arachne) (c. 1657) -Oil on canvas, 167 × 252 cm, Museo del Prado, Madrid

- Mercury and Argus (1659) - Oil on canvas, 127 × 248 cm, Museo del Prado, Madrid

Notes

- ↑ Yasujiro Otaka, "An Aspiration Sealed: Velazquez, from a commoner to the Caballero de Santiago," Studies in Western Art 4 (September 2000), Online summary Retrieved on March 10, 2007.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Lillian Zirpolo, "Madre Jeronima de la Fuente and Lady With A Fan Two Portraits Reexamined," Woman's Art Journal 15 (1) (Spring - Summer, 1994): 16-21,

- ↑ Great Masters Gallery, Diego Rodriguez de Silva Velazquez Art Reproductions' - Main Page, Velazquez Art Reproductions Retrieved June 24, 2007.

- ↑ Great Masters Gallery, Diego Rodriguez de Silva Velazquez Art Reproductions - The Lady with a Fan, The Lady with a Fan, c.1630/50, The Wallace Collection, London, UK Retrieved June 24, 2007.

- ↑ Zahira Veliz, "Signs of identity in Lady with a Fan by Diego Velazquez: Costume and Likeness Reconsidered - Critical Essay," The Art Bulletin (March 2004), Signs of identity in Lady with a Fan by Diego Velazquez Retrieved June 24, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Brown, Dale. The World of Velázquez: 1599–1660. New York: Time-Life Books, 1969. ISBN 0809402521

- Brown, Jonathan. Images and Ideas in Seventeenth-Century Spanish Painting. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1978. ISBN 0691039410

- Brown, Jonathan. Velázquez: Painter and Courtier. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1986. ISBN 0300034660

- Calvo Serraller, Francisco. Velázquez. Madrid: Electa, 1999. ISBN 8481562033

- Davies, David, and Enriqueta Harris. Velázquez in Seville. Edinburgh: National Gallery of Scotland, 1996. ISBN 0300069499

- Erenkrantz, Justin R. The Mask and the Mirror. The Variations on Past Masters Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- Goldberg, Edward L. "Velázquez in Italy: Painters, Spies and Low Spaniards." The Art Bulletin 74(3) (September 1992): 453-456.

- Great Masters Gallery. Diego Rodriguez de Silva Velazquez Art Reproductions - Main Page. Velazquez Art Reproductions Retrieved June 24, 2007.

- Great Masters Gallery. Diego Rodriguez de Silva Velazquez Art Reproductions - The Lady with a Fan. The Lady with a Fan, c.1630/50, The Wallace Collection, London, UK Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- Otaka, Yasujiro. "An Aspiration Sealed: Velazquez, from a commoner to the Caballero de Santiago." Studies in Western Art 4 (September 2000). Online summary Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- Veliz, Zahira. "Signs of identity in Lady with a Fan by Diego Velazquez: Costume and Likeness Reconsidered - Critical Essay." The Art Bulletin (March 2004).

- Wolf, Norbert. Diego Velázquez, 1599-1660: the face of Spain. Köln: Taschen, 1998. ISBN 3822865117

- Zirpolo, Lillian. "Madre Jeronima de la Fuente and Lady With A Fan Two Portraits Reexamined." Woman's Art Journal 15(1) (Spring - Summer, 1994): 16-21. Jstor Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

External links

All links retrieved January 29, 2024.

- Diego Velázquez at the Art Renewal Center.

- Diego Velázquez at Artcyclopedia.com.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.