El Greco

| El Greco | |

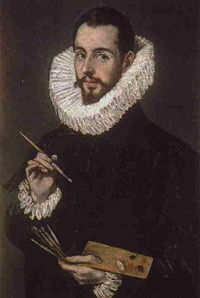

Portrait of An Old Man (so called self-portrait of El Greco), circa 1595-1600, oil on canvas, 52.7 x 46.7 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City) | |

| Birth name | Doménicos Theotocópoulos |

| Born | 1541 Crete, Republic of Venice |

| Died | April 7, 1614 Toledo, Spain |

| Field | Painting, sculpture and architecture |

| Movement | Mannerism, Antinaturalism |

| Famous works | El Espolio (1577-1579) The Assumption of the Virgin (1577-1579) The Burial of the Count of Orgaz (1586-1588) View of Toledo (1596-1600) Opening of the Fifth Seal (1608-1614) |

El Greco (probably a combination of the Castilian and the Venetian language for "The Greek",[a][b] 1541 â April 7, 1614) was a prominent painter, sculptor, and architect of the Spanish Renaissance. He usually signed his paintings in Greek letters with his full name, DomĂ©nicos TheotocĂłpoulos (Greek: ÎÎżÎŒÎźÎœÎčÎșÎżÏ ÎΔοÏÎżÎșÏÏÎżÏ Î»ÎżÏ), underscoring his Greek descent.

El Greco was born in Crete, which was at that time part of the Republic of Venice; following a trend common amongst young sixteenth and seventeenth century Greeks pursuing a wider education, at 26 he travelled to Venice to study. In 1570 he moved to Rome, where he opened a workshop and executed a series of works. During his stay in Italy, El Greco enriched his style with elements of Mannerism and of the Venetian Renaissance. In 1577 he emigrated to Toledo, Spain, where he lived and worked until his death. In Toledo, El Greco received several major commissions and produced his best known paintings.

El Greco's dramatic and expressionistic style was met with puzzlement by his contemporaries but found appreciation in the twentieth century. El Greco is regarded as a precursor of both Expressionism and Cubism, while his personality and works were a source of inspiration for poets and writers such as Rainer Maria Rilke and Nikos Kazantzakis. El Greco has been characterized by modern scholars as an artist so individual that he belongs to no conventional school.[1] He is best known for tortuously elongated figures and often fantastic or phantasmagorical pigmentation, marrying Byzantine traditions with those of Western civilization.[2]

Life

Early years and family

Born in 1541 in either the village of Fodele or Candia (the Venetian name of Chandax, present day Heraklion) in Crete,[c] El Greco descended from a prosperous urban family, which had probably been driven out of Chania to Candia after an uprising against the Venetians between 1526 and 1528.[3] El Greco's father, GeĂłrgios TheotocĂłpoulos (d. 1556), was a merchant and tax collector. Nothing is known about his mother or his first wife, a Greek.[4] El Greco's older brother, ManoĂșssos TheotocĂłpoulos (1531-December 13, 1604), was a wealthy merchant who spent the last years of his life (1603-1604) in El Greco's Toledo home.[5]

El Greco received his initial training as an icon painter. In addition to painting, he studied the classics, ancient Greek, and Latinâ this is confirmed by the large library he left after his death.[3] He received a humanistic education in Candia, a center for artistic activity and a melting pot of Eastern and Western cultures. Around two hundred painters were active in Candia in the sixteenth century, and had organized guilds, based on the Italian model.[3] In 1563, at the age of 22, El Greco was described in a document as a "master" ("maestro Domenigo"), meaning he was already officially practicing the profession of painting.[6] Three years later, in June 1566, as a witness to a contract, he signed his name as Master MenĂ©gos TheotocĂłpoulos, painter (ΌαÎÏÏÏÎżÏ ÎÎÎœÎ”ÎłÎżÏ ÎΔοÏÎżÎșÏÏÎżÏ Î»ÎżÏ ÏÎłÎżÏ ÏÎŹÏÎżÏ).[d]

It is an open question whether El Greco was given a Roman Catholic or Greek Orthodox rite at birth. The lack of Orthodox archival baptismal records on Crete, and a relaxed interchange between Greek Orthodox and Roman Catholic rites during his youth, means that El Greco's birth rite remains a matter of conjecture. Based on the assessment that his art reflects the religious spirit of Roman Catholic Spain, and on a reference in his last will and testament, where he described himself as a "devout Catholic," some scholars assume that El Greco was part of the vibrant Catholic Cretan minority or that he converted from Greek Orthodoxy to Roman Catholicism before leaving the island.[7] On the other hand, based on the extensive archival research that they conducted since the early 1960s, other scholars, such as Nikolaos Panayotakis, Pandelis Prevelakis and Maria Constantoudaki, insist that El Greco's family and ancestors were Greek Orthodox. They underscore that one of his uncles was an Orthodox priest, and that his name is not mentioned in the Catholic archival baptismal records on Crete.[8] Prevelakis goes even further, expressing his doubt that El Greco was ever a practicing Roman Catholic.[9]

In Italy

As a Venetian citizen (Crete had been a possession of the Republic of Venice since 1211), it was natural for the young El Greco to pursue his studies in Venice.[1] Though the exact year is not clear, most scholars agree that El Greco went to Venice around 1567.[e] Knowledge of El Greco's years in Italy is limited. He lived in Venice until 1570 and, according to a letter written by the Croatian miniaturist, Giulio Clovio, he entered the studio of Titian, who was by then in his eighties but still vigorous. Clovio characterized El Greco as "a rare talent in painting".[10]

In 1570 El Greco moved to Rome, where he executed a series of works strongly marked by his Venetian apprenticeship.[10] It is unknown how long he remained in Rome, though he may have returned to Venice (c. 1575-1576) before he left for Spain.[11] In Rome, El Greco was received as a guest at the fabled palace of Alessandro Cardinal Farnese (Palazzo Farnese), where the young Cretan painter came into contact with the intellectual elite of the city. He associated with the Roman scholar Fulvio Orsini, whose collection would later include seven paintings by the artist (View of Mt. Sinai and a portrait of Clovio are among them).[12]

Unlike other Cretan artists who had moved to Venice, El Greco substantially altered his style and sought to distinguish himself by inventing new and unusual interpretations of traditional religious subject matter.[13] His works painted in Italy are influenced by the Venetian Renaissance style of the period, with agile, elongated figures reminiscent of Tintoretto and a chromatic framework that connects him to Titian.[1] The Venetian painters also taught him to organize his multi-figured compositions in landscapes vibrant with atmospheric light. Clovio reports visiting El Greco on a summer's day while the artist was still in Rome. El Greco was sitting in a darkened room, because he found the darkness more conducive to thought than the light of the day, which disturbed his "inner light".[14] As a result of his stay in Rome, his works were enriched with elements such as violent perspective vanishing points or strange attitudes struck by the figures with their repeated twisting and turning and tempestuous gestures; all elements of Mannerism.[10]

By the time El Greco arrived in Rome, both Michelangelo and Raphael were deceased, but their example remained paramount and left little room for different approaches. Although the artistic heritage of these great masters was overwhelming for young painters, El Greco was determined to make his own mark in Rome, defending his personal artistic views, ideas and style.[15] He singled out Correggio and Parmigianino for particular praise,[16] but he did not hesitate to dismiss Michelangelo's Last Judgment in the Sistine Chapel;[f] he extended an offer to Pope Pius V to paint over the whole work in accord with the new and stricter Catholic thinking.[17] When he was later asked what he thought about Michelangelo, El Greco replied that "he was a good man, but he did not know how to paint".[18] Still, while he condemned Michelangelo, he found it impossible to withstand his influence.[19] Michelangelo's influence can be seen in later El Greco works such as the Allegory of the Holy League.[20] By painting portraits of Michelangelo, Titian, Clovio and, presumably, Raphael in one of his works (The Purification of the Temple), El Greco not only expressed his gratitude but advanced the claim to rival these masters. As his own commentaries indicate, El Greco viewed Titian, Michelangelo and Raphael as models to emulate.[17] In his seventeenth century Chronicles, Giulio Mancini included El Greco among the painters who had initiated, in various ways, a re-evaluation of Michelangelo's teachings.[21]

Because of his unconventional artistic beliefs (such as his dismissal of Michelangelo's technique) and personality, El Greco soon acquired enemies in Rome. Architect and writer Pirro Ligorio called him a "foolish foreigner," and newly discovered archival material reveals a skirmish with Farnese, who obliged the young artist to leave his palace.[21] On July 6, 1572, El Greco officially complained about this event. A few months later, on September 18 1572, El Greco paid his dues to the guild of St. Luke in Rome as a miniature painter.[22] At the end of that year, El Greco opened his own workshop and hired as assistants the painters Lattanzio Bonastri de Lucignano and Francisco Preboste.[21]

Emigration to Toledo, Spain

In 1577, El Greco emigrated first to Madrid, then to Toledo, where he produced his mature works.[23] At the time, Toledo was the religious capital of Spain and a populous city[g] with "an illustrious past, a prosperous present and an uncertain future".[24] In Rome, El Greco had earned the respect of some intellectuals, but was also facing the hostility of certain art critics.[25] During the 1570s the palace of El Escorial was still under construction and Philip II of Spain had invited the artistic world of Italy to come and decorate it. Through Clovio and Orsini, El Greco met Benito Arias Montano, a Spanish humanist and delegate of Philip; Pedro ChacĂłn, a clergyman; and Luis de Castilla, son of Diego de Castilla, the dean of the Cathedral of Toledo.[26] El Greco's friendship with Castilla would secure his first large commissions in Toledo. He arrived in Toledo by July 1577, and signed contracts for a group of paintings that was to adorn the church of Santo Domingo el Antiguo at El Escorial and for the renowned El Espolio.[27] By September 1579 he had completed nine paintings for Santo Domingo, including The Trinity and The Assumption of the Virgin. These works would establish the painter's reputation in Toledo.[22]

El Greco did not plan to settle permanently in Toledo, since his final aim was to win the favor of Philip and make his mark in his court.[28] He managed to secure two important commissions from the monarch: Allegory of the Holy League and Martyrdrom of St. Maurice. However, the king did not like these works and gave no further commission to El Greco.[29] The exact reasons of the king's dissatisfaction remain unclear. Some scholars have suggested that Philip did not like the inclusion of a living person in a historical scene[29]; some others that El Greco's works violated a basic rule of the Counter-Reformation, namely that in the image the content was paramount rather than the style.[30] In either case, Philip's dissatisfaction ended any hopes of royal patronage El Greco may have had.[22]

Mature works and later years

Lacking the favor of the king, El Greco was obliged to remain in Toledo, where he had been received in 1577 as a great painter.[31] According to Hortensio FĂ©lix Paravicino, a seventeenth-century Spanish preacher and poet, "Crete gave him life and the painterâs craft, Toledo a better homeland, where through Death he began to achieve eternal life."[32] In 1585, he appears to have hired an assistant, Italian painter Francisco Preboste, and to have established a workshop capable of producing altar frames and statues as well as paintings.[33] On March 12 1586 he obtained the commission for The Burial of the Count of Orgaz, now his best-known work.[34] The decade 1597 to 1607 was a period of intense activity for El Greco. During these years he received several major commissions, and his workshop created pictorial and sculptural ensembles for a variety of religious institutions. Among his major commissions of this period were three altars for the Chapel of San JosĂ© in Toledo (1597â1599); three paintings (1596â1600) for the Colegio de Doña MarĂa de Aragon, an Augustinian monastery in Madrid, and the high altar, four lateral altars, and the painting St. Ildefonso for the Capilla Mayor of the Hospital de la Caridad (Hospital of Charity) at Illescas, Toledo (1603â1605). The minutes of the commission of The Virgin of the Immaculate Conception (1607-1613), which were composed by the personnel of the municipality, describe El Greco as "one of the greatest men in both this kingdom and outside it".[35]

Between 1607 and 1608 El Greco was involved in a protracted legal dispute with the authorities of the Hospital of Charity at Illescas concerning payment for his work, which included painting, sculpture and architecture;[h] this and other legal disputes contributed to the economic difficulties he experienced towards the end of his life.[36] In 1608, he received his last major commission: for the Hospital of Saint John the Baptist in Toledo.

El Greco made Toledo his home. Surviving contracts mention him as the tenant from 1585 onwards of a complex consisting of three apartments and 24 rooms which belonged to the Marquis de Villena.[37] It was in these apartments, which also served as his workshop, that he passed the rest of his life, painting and studying. It is not confirmed whether he lived with his Spanish female companion, JerĂłnima de Las Cuevas, whom he probably never married. She was the mother of his only son, Jorge Manuel, born in 1578.[i] In 1604, Jorge Manuel and Alfonsa de los Morales gave birth to El Greco's grandson, Gabriel, who was baptized by Gregorio Angulo, governor of Toledo and a personal friend of the artist.[36]

During the course of the execution of a commission for the Hospital Tavera, El Greco fell seriously ill, and a month later, on April 7, 1614, he died. A few days earlier, on March 31, he had directed that his son should have the power to make his will. Two Greeks, friends of the painter, witnessed this last will and testament (El Greco never lost touch with his Greek origins).[38] He was buried in the Church of Santo Domingo el Antigua.[39]

Technique and style

The primacy of imagination and intuition over the subjective character of creation was a fundamental principle of El Greco's style.[18] El Greco discarded classicist criteria such as measure and proportion. He believed that grace is the supreme quest of art, but the painter achieves grace only if he manages to solve the most complex problems with obvious ease.[18]

| "I hold the imitation of color to be the greatest difficulty of art." |

| El Greco (notes of the painter in one of his commentaries)[40] |

El Greco regarded color as the most important and the most ungovernable element of painting, and declared that color had primacy over form.[18] Francisco Pacheco, a painter and theoretician who visited El Greco in 1611, wrote that the painter liked "the colors crude and unblent in great blots as a boastful display of his dexterity" and that "he believed in constant repainting and retouching in order to make the broad masses tell flat as in nature".[41]

Art historian Max DvoĆĂĄk was the first scholar to connect El Greco's art with Mannerism and Antinaturalism.[42] Modern scholars characterize El Greco's theory as "typically Mannerist" and pinpoint its sources in the Neo-Platonism of the Renaissance.[43] Jonathan Brown believes that El Greco endeavored to create a sophisticated form of art;[44] according to Nicholas Penny "once in Spain, El Greco was able to create a style of his ownâone that disavowed most of the descriptive ambitions of painting".[45]

In his mature works El Greco tended to dramatize his subjects rather than to describe. The strong spiritual emotion transfers from painting directly to the audience. According to Pacheco, El Greco's perturbed, violent and at times carelessly executed art was due to a studied effort to acquire a freedom of style.[41] El Greco's preference for exceptionally tall and slender figures and elongated compositions, which served both his expressive purposes and aesthetic principles, led him to disregard the laws of nature and elongate his compositions to ever greater extents, particularly when they were destined for altarpieces.[46] The anatomy of the human body becomes even more otherworldly in El Greco's mature works; for The Virgin of the Immaculate Conception El Greco asked to lengthen the altarpiece itself by another 1.5 feet "because in this way the form will be perfect and not reduced, which is the worst thing that can happen to a figure'." A significant innovation of El Greco's mature works is the interweaving between form and space; a reciprocal relationship is developed between the two which completely unifies the painting surface. This interweaving would re-emerge three centuries later in the works of CĂ©zanne and Picasso.[46]

Another characteristic of El Greco's mature style is the use of light. As Jonathan Brown notes, "each figure seems to carry its own light within or reflects the light that emanates from an unseen source".[47] Fernando Marias and AgustĂn Bustamante GarcĂa, the scholars who transcribed El Greco's handwritten notes, connect the power that the painter gives to light with the ideas underlying Christian Neo-Platonism.[48]

Modern scholarly research emphasizes on the importance of Toledo for the complete development of El Greco's mature style and stresses the painter's ability to adjust his style in accordance with his surroundings.[49] Harold Wethey asserts that "although Greek by descent and Italian by artistic preparation, the artist became so immersed in the religious environment of Spain that he became the most vital visual representative of Spanish mysticism." He believes that in El Greco's mature works "the devotional intensity of mood reflects the religious spirit of Roman Catholic Spain in the period of the Counter-Reformation".[1]

El Greco also excelled as a portraitist, able not only to record a sitter's features but also to convey their character.[50] His portraits are fewer in number than his religious paintings, but are of equally high quality. Wethey says that "by such simple means, the artist created a memorable characterization that places him in the highest rank as a portraitist, along with Titian and Rembrandt".[1]

Suggested Byzantine affinities

Since the beginning of the twentieth century, scholars have debated whether El Greco's style had Byzantine origins. Certain art historians had asserted that El Greco's roots were firmly in the Byzantine tradition, and that his most individual characteristics derive directly from the art of his ancestors,[51] while, others had argued that Byzantine art could not be related to El Greco's later work.[52]

The discovery of the Dormition of the Virgin on Syros, an authentic and signed work from the painter's Cretan period, and the extensive archival research in the early 1960s, contributed to the rekindling and reassessment of these theories. Significant scholarly works of the second half of the twentieth century devoted to El Greco reappraise many of the interpretations of his work, including his supposed Byzantinism.[53] Based on the notes written in El Greco's own hand, on his unique style, and on the fact that El Greco signed his name in Greek characters, they see an organic continuity between Byzantine painting and his art.[54] According to Marina Lambraki-Plaka "far from the influence of Italy, in a neutral place which was intellectually similar to his birthplace, Candia, the Byzantine elements of his education emerged and played a catalytic role in the new conception of the image which is presented to us in his mature work".[55] In making this judgment, Lambraki-Plaka disagrees with Oxford University professors Cyril Mango and Elizabeth Jeffreys, who assert that "despite claims to the contrary, the only Byzantine element of his famous paintings was his signature in Greek lettering".[56] Nicos Hadjinicolaou states that from 1570 El Greco's painting is "neither Byzantine nor post-Byzantine but Western European. The works he produced in Italy belong to the history of the Italian art, and those he produced in Spain to the history of Spanish art".[57]

The English art historian David Davies seeks the roots of El Greco's style in the intellectual sources of his Greek-Christian education and in the world of his recollections from the liturgical and ceremonial aspect of the Orthodox Church. Davies believes that the religious climate of the Counter-Reformation and the aesthetics of mannerism acted as catalysts to activate his individual technique. He asserts that the philosophies of Platonism and ancient Neo-Platonism, the works of Plotinus and Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, the texts of the Church fathers and the liturgy offer the keys to the understanding of El Greco's style.[58] Summarizing the ensuing scholarly debate on this issue, JosĂ© Ălvarez Lopera, curator at the Museo del Prado, Madrid, concludes that the presence of "Byzantine memories" is obvious in El Greco's mature works, though there are still some obscure issues concerning his Byzantine origins needing further illumination.[59]

Architecture and sculpture

El Greco was highly esteemed as an architect and sculptor during his lifetime. He usually designed complete altar compositions, working as architect and sculptor as well as painter â at, for instance, the Hospital de la Caridad. There he decorated the chapel of the hospital, but the wooden altar and the sculptures he created have in all probability perished.[60] For El Espolio the master designed the original altar of gilded wood which has been destroyed, but his small sculptured group of the Miracle of Saint Ildefonso still survives on the lower center of the frame.[1]

| "I would not be happy to see a beautiful, well-proportioned woman, no matter from which point of view, however extravagant, not only lose her beauty in order to, I would say, increase in size according to the law of vision, but no longer appear beautiful, and, in fact, become monstrous." |

| El Greco (marginalia the painter inscribed in his copy of Daniele Barbaro's translation of Vitruvius)[61] |

His most important architectural achievement was the church and Monastery of Santo Domingo el Antiguo, for which he also executed sculptures and paintings.[62] El Greco is regarded as a painter who incorporated architecture in his painting.[63] He is also credited with the architectural frames to his own paintings in Toledo. Pacheco characterized him as "a writer of painting, sculpture and architecture".[18]

In the marginalia that El Greco inscribed in his copy of Daniele Barbaro's translation of Vitruvius' De Architectura, he refuted Vitruvius' attachment to archaeological remains, canonical proportions, perspective and mathematics. He also saw Vitruvius's manner of distorting proportions in order to compensate for distance from the eye as responsible for creating monstrous forms. El Greco was averse to the very idea of rules in architecture; he believed above all in the freedom of invention and defended novelty, variety, and complexity. These ideas were, however, far too extreme for the architectural circles of his era and had no immediate resonance.[63]

Legacy

Posthumous critical reputation

| â | It was a great moment. A pure righteous conscience stood on one tray of the balance, an empire on the other, and it was you, man's conscience, that tipped the scales. This conscience will be able to stand before the Lord as the Last Judgement and not be judged. It will judge, because human dignity, purity and valor fill even God with terror âŠ. Art is not submission and rules, but a demon which smashes the moulds âŠ. Greco's inner-archangel's breast had thrust him on savage freedom's single hope, this world's most excellent garret. | â |

| Â | â Nikos Kazantzakis, Report to Greco

|

El Greco was disdained by the immediate generations after his death because his work was opposed in many respects to the principles of the early baroque style which came to the fore near the beginning of the seventeenth century and soon supplanted the last surviving traits of the sixteenth-century Mannerism.[1] El Greco was deemed incomprehensible and had no important followers.[64] Only his son and a few unknown painters produced weak copies of his works. Late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century Spanish commentators praised his skill but criticized his antinaturalistic style and his complex iconography. Some of these commentators, such as Acislo Antonio Palomino de Castro y Velasco and Juan AgustĂn CeĂĄn BermĂșdez, described his mature work as "contemptible," "ridiculous" and "worthy of scorn".[65] The views of Palomino and BermĂșdez were frequently repeated in Spanish historiography, adorned with terms such as "strange," "queer," "original," "eccentric" and "odd".[66] The phrase "sunk in eccentricity," often encountered in such texts, in time developed into "madness".[j]

With the arrival of Romantic sentiments in the late eighteenth century, El Greco's works were examined anew.[64] To French writer Theophile Gautier, El Greco was the precursor of the European Romantic movement in all its craving for the strange and the exteme.[67] Gautier regarded El Greco as the ideal romatic hero (the "gifted," the "misunderstood," the "mad"[j]), and was the first who explicitely expressed his admiration for El Greco's later technique.[66] French art critics Zacharie Astruc and Paul Lefort helped to promote a widespread revival of interest in his painting. In the 1890s, Spanish painters living in Paris adopted him as their guide and mentor.[67]

In 1908, Spanish art historian Manuel BartolomĂ© CossĂo published the first comprehensive catalogue of El Greco's works; in this book El Greco was presented as the founder of the Spanish School.[68] The same year Julius Meier-Graefe, a scholar of French Impressionism, travelled in Spain and recorded his experiences in The Spanische Reise, the first book which established El Greco as a great painter of the past. In El Greco's work, Meier-Graefe found foreshadowings of modernity.[69] These are the words Meier-Graefe used to describe El Greco's impact on the artistic movements of his time:

He [El Greco] has discovered a realm of new possibilities. Not even he, himself, was able to exhaust them. All the generations that follow after him live in his realm. There is a greater difference between him and Titian, his master, than between him and Renoir or CĂ©zanne. Nevertheless, Renoir and CĂ©zanne are masters of impeccable originality because it is not possible to avail yourself of El Greco's language, if in using it, it is not invented again and again, by the user.[70]

To the English artist and critic Roger Fry in 1920, El Greco was the archetypal genius who did as he thought best "with complete indifference to what effect the right expression might have on the public." Fry described El Greco as "an old master who is not merely modern, but actually appears a good many steps ahead of us, turning back to show us the way".[16] During the same period, other researchers developed alternate, more radical theories. Doctors August Goldschmidt and GermĂĄn Beritens argued that El Greco painted such elongated human figures because he had vision problems (possibly progressive astigmatism or strabismus) that made him see bodies longer than they were, and at an angle to the perpendicular.[k] English writer W. Somerset Maugham attributed El Greco's personal style to the artist's "latent homosexuality," and doctor Arturo Perera to the use of marijuana.[71]

| "As I was climbing the narrow, rain-slicked lane -nearly three hundred years have gone by- which this time were full of |

| âOdysseas Elytis, Diary of an Unseen April |

Michael Kimmelman, art reviewer for The New York Times, stated that "to Greeks [El Greco] became the quintessential Greek painter; to the Spanish, the quintessential Spaniard".[16] As was proved by the campaign of the National Art Gallery in Athens to raise the funds for the purchase of Saint Peter in 1995, El Greco is not loved just by experts and art lovers but also by ordinary people; thanks to the donations mainly of individuals and public benefit foundations the National Art Gallery raised 1.2 million dollars and purchased the painting.[72] Epitomizing the general consensus of El Greco's impact, Jimmy Carter, the 39th President of the United States, said in April 1980 that El Greco was "the most extraordinary painter that ever came along back then" and that he was "maybe three or four centuries ahead of his time".[67]

Influence on other artists

El Greco's re-evaluation was not limited to scholars. According to Efi Foundoulaki, "painters and theoreticians from the beginning of the twentieth century 'discovered' a new El Greco, but in process they also discovered and revealed their own selves".[73] His expressiveness and colors influenced EugĂšne Delacroix and Ădouard Manet.[74] To the Blaue Reiter group in Munich in 1912, El Greco typified that mystical inner construction that it was the task of their generation to rediscover.[75] The first painter who appears to have noticed the structural code in the morphology of the mature El Greco was Paul CĂ©zanne, one of the forerunners of Cubism.[64] Comparative morphological analyses of the two painters revealed their common elements, such as the distortion of the human body, the reddish and (in appearance only) unworked backgrounds and the similarities in the rendering of space.[76] According to Brown, "CĂ©zanne and El Greco are spiritual brothers despite the centuries which separate them".[77] Fry observed that CĂ©zanne drew from "his great discovery of the permeation of every part of the design with a uniform and continuous plastic theme".[78]

The symbolists, and Pablo Picasso during his Blue Period, drew on the cold tonality of El Greco, utilizing the anatomy of his ascetic figures. While Picasso was working on Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, he visited his friend Ignacio Zuloaga in his studio in Paris and studied El Greco's Opening of the Fifth Seal (owned by Zuloaga since 1897).[79] The relation between Les Demoiselles d'Avignon and the Opening of the Fifth Seal was pinpointed in the early 1980s, when the stylistic similarities and the relationship between the motifs of both works were analysed.[80]

| "In any case, only the execution counts. From this point of view, it is correct to say that Cubism has a Spanish origin and that I invented Cubism. We must look for the Spanish influence in CĂ©zanne. Things themselves necessitate it, the influence of El Greco, a Venetian painter, on him. But his structure is Cubist." |

| Picasso speaking of "Les Demoiselles d'Avignon" to Dor de la SouchĂšre in Antibes.[81] |

The early cubist explorations of Picasso were to uncover other aspects in the work of El Greco: structural analysis of his compositions, multi-faced refraction of form, interweaving of form and space, and special effects of highlights. Several traits of cubism, such as distortions and the materialistic rendering of time, have their analogies in El Greco's work. According to Picasso, El Greco's structure is cubist.[82] On February 22 1950, Picasso began his series of "paraphrases" of other painters' works with The Portrait of a Painter after El Greco.[83] Foundoulaki asserts that Picasso "completed ⊠the process for the activation of the painterly values of El Greco which had been started by Manet and carried on by Cézanne".[84]

The expressionists focused on the expressive distortions of El Greco. According to Franz Marc, one of the principal painters of the German expressionist movement, "we refer with pleasure and with steadfastness to the case of El Greco, because the glory of this painter is closely tied to the evolution of our new perceptions on art".[85] Jackson Pollock, a major force in the abstract expressionist movement, was also influenced by El Greco. By 1943, Pollock had completed 60 drawing compositions after El Greco and owned three books on the Cretan master.[86]

Contemporary painters are also inspired by El Greco's art. Kysa Johnson used El Greco's paintings of the Immaculate Conception as the compositional framework for some of her works, and the master's anatomical distortions are somewhat reflected in Fritz Chesnut's portraits.[87]

El Greco's personality and work were a source of inspiration for poet Rainer Maria Rilke. One set of Rilke's poems (Himmelfahrt Mariae I.II., 1913) was based directly on El Greco's Immaculate Conception.[88] Greek writer Nikos Kazantzakis, who felt a great spiritual affinity for El Greco, called his autobiography Report to Greco and wrote a tribute to the Cretan-born artist.[89]

In 1998, the Greek electronic composer and artist Vangelis published El Greco (album), a symphonic album inspired by the artist. This album is an expansion of an earlier album by Vangelis, Foros Timis Ston Greco (A Tribute to El Greco, Greek: ΊÏÏÎżÏ Î€ÎčÎŒÎźÏ ÎŁÏÎżÎœ ÎÎșÏÎÎșÎż). The life of the Cretan-born artist is to be the subject of an ambitious Greek-Spanish film. Directed by Yannis Smaragdis, the film began shooting in October 2006 on the island of Crete; British actor Nick Ashdon has been cast to play El Greco.[90]

Debates on attribution

The exact number of El Greco's works has been a hotly contested issue. In 1937 a highly influential study by art historian Rodolfo Pallucchini had the effect of greatly increasing the number of works accepted to be by El Greco. Palluchini attributed to El Greco a small triptych in the Galleria Estense at Modena on the basis of a signature on the painting on the back of the central panel on the Modena triptych ("Î§Î”ÎŻÏ ÎÎżÎŒÎźÎœÎčÏÎżÏ ," Created by the hand of DomĂ©nicos).[91] There was consensus that the triptych was indeed an early work of El Greco and, therefore, Pallucchini's publication became the yardstick for attributions to the artist.[92] Nevertheless, Wethey denied that the Modena triptych had any connection at all with the artist and, in 1962, produced a reactive catalogue raisonnĂ© with a greatly reduced corpus of materials. Whereas art historian JosĂ© CamĂłn Aznar had attributed between 787 and 829 paintings to the Cretan master, Wethey reduced the number to 285 authentic works and Halldor SĆhner, a German researcher of Spanish art, recognized only 137.[93] Wethey and other scholars rejected the notion that Crete took any part in his formation and supported the elimination of a series of works from El Greco's oeuvre.[94]

Since 1962 the discovery of the Dormition and the extensive archival research has gradually convinced scholars that Wethey's assessments were not entirely correct, and that his catalogue decisions may have distorted the perception of the whole nature of El Greco's origins, development and oeuvre. The discovery of the Dormition led to the attribution of three other signed works of "DomĂ©nicos" to El Greco (Modena Triptych, Saint Luke Painting the Virgin and Child, and The Adoration of the Magi) and then to the acceptance of more works as authentic â some signed, some not (such as The Passion of Christ (PietĂ with Angels) painted in 1566),[95] â which were brought into the group of early works of El Greco. El Greco is now seen as an artist with a formative training on Crete; a series of works illuminate the style of early El Greco, some painted while he was still in Crete, some from his period in Venice, and some from his subsequent stay in Rome.[53] Even Wethey accepted that "he [El Greco] probably had painted the little and much disputed triptych in the Galleria Estense at Modena before he left Crete".[96] Nevertheless, disputes over the exact number of El Greco's authentic works remain unresolved, and the status of Wethey's catalogue raisonnĂ© is at the centre of these disagreements.[97]

A few sculptures, including Epimetheus and Pandora, have been attributed to El Greco. This doubtful attribution is based on the testimony of Pacheco (he saw in El Greco's studio a series of figurines, but these may have been merely models).[98] There are also four drawings among the surviving works of El Greco; three of them are preparatory works for the altarpiece of Santo Domingo el Antiguo and the fourth is a study for one of his paintings, The Crucifixion.[99]

Commentary

a. TheotocĂłpoulos acquired the name "El Greco" in Italy, where the custom of identifying a man by designating a country or city of origin was a common practice. The curious form of the article (El) may be from the Venetian dialect or more likely from the Spanish, though in Spanish his name would be "El Griego".[1] The Cretan master was generally known in Italy and Spain as Dominico Greco, and was called only after his death El Greco.[53]

b. According to a contemporary, El Greco acquired his name, not only for his place of origin, but also for the sublimity of his art: "Out of the great esteem he was held in he was called the Greek (il Greco)" (comment of Giulio Cesare Mancini about El Greco in his Chronicles, which were written a few years after El Greco's death).[100]

c. There is an ongoing dispute about El Greco's birthplace. Most researchers and scholars give Candia as his birthplace.[101] Nonetheless, according to Achileus A. Kyrou, a prominent Greek journalist of the twentieth century, El Greco was born in Fodele and the ruins of his family's house are still extant in the place where old Fodele was (the village later changed location because of the raids of the pirates).[37] Candia's claim to him is based on two documents from a trial in 1606, when the painter was 65, stating his place of birth as Candia. Fodele natives argue that El Greco probably told everyone in Spain he was from Heraklion because it was the closest known city next to tiny Fodele[102]

d. This document comes from the notarial archives of Candia and was published in 1962.[103] Menegos is the Venetian dialect form of DomĂ©nicos, and Sgourafos (ÏÎłÎżÏ ÏÎŹÏÎżÏ=ζÏÎłÏÎŹÏÎżÏ) is a Greek term for painter.[53]

e. According to archival research in the late 1990s, El Greco was still in Candia at the age of 26. It was there where his works, created in the spirit of the post-Byzantine painters of the Cretan School, were greatly esteemed. On December 26, 1566, El Greco sought permission from the Venetian authorities to sell a "panel of the Passion of Christ executed on a gold background" ("un quadro della Passione del Nostro Signor Giesu Christo, dorato") in a lottery.[53] The Byzantine icon by young DomĂ©nicos depicting the Passion of Christ, painted on a gold ground, was appraised and sold on December 27, 1566, in Candia for the agreed price of seventy gold ducats (The panel was valued by two artists; one of them was icon-painter Georgios Klontzas. One valuation was eighty ducats and the other seventy), equal in value to a work by Titian or Tintoretto of that period.[104] Therefore, it seems that El Greco traveled to Venice sometime after December 27, 1566.[105] In one of his last articles, Wethey reassessed his previous estimations and accepted that El Greco left Crete in 1567.[96] According to other archival materialâdrawings El Greco sent to a Cretan cartographerâhe was in Venice by 1568.[104]

f. Mancini reports that El Greco said to the Pope that if the whole work was demolished he himself would do it in a decent manner and with seemliness.[106]

g. Toledo must have been one of the largest cities in Europe during this period. In 1571 the population of the city was 62,000.[26]

h. El Greco signed the contract for the decoration of the high altar of the church of the Hospital of Charity on June 18, 1603. He agreed to finish the work by August of the following year. Although such deadlines were seldom met, it was a point of potential conflict. He also agreed to allow the brotherhood to select the appraisers.[107] The brotherhood took advantage of this act of good faith and did not wish to arrive at a fair settlement.[108] Finally, El Greco assigned his legal representation to Preboste and a friend of him, Francisco Ximénez Montero, and accepted a payment of 2,093 ducats.[109]

i. Doña Jerónima de Las Cuevas appears to have outlived El Greco, and, although the master acknowledged both her and his son, he never married her. That fact has puzzled researchers, because he mentioned her in various documents, including his last testament. Most analysts assume that El Greco had married unhappily in his youth and therefore could not legalize another attachment.[1]

j. The myth of El Greco's madness came in two versions. On the one hand Gautier believed that El Greco went mad from excessive artistic sensitivity.[110] On the other hand, the public and the critics would not possess the ideological criteria of Gautier and would retain the image of El Greco as a "mad painter" and, therefore, his "maddest" paintings were not admired but considered to be historical documents proving his "madness".[66]

k. This theory enjoyed surprising popularity during the early years of the twentieth century and was opposed by the German psychologist David Kuntz.[111]. Whether or not El Greco had progressive astigmatism is still open to debate.[112] Stuart Anstis, Professor at the University of California (Department of Psychology), concludes that "even if El Greco were astigmatic, he would have adapted to it, and his figures, whether drawn from memory or life, would have had normal proportions. His elongations were an artistic expression, not a visual symptom."[113] According to Professor of Spanish John Armstrong Crow, "astigmatism could never give quality to a canvas, nor talent to a dunce".[114]

Notes

- â 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 "Greco, El" Encyclopaedia Britannica 2002.

- â Marina Lambraki-Plaka. El Greco-The Greek. (Athens: Kastaniotis Editions, 1999. ISBN 9600325448), 60

- â 3.0 3.1 3.2 Lambraki-Plaka, 1999, 40-41

- â Michael Scholz-Hansel. El Greco. (Taschen, 1986. ISBN 3822831719), 7

Mauricia Tazartes. El Greco, translated in Greek by Sofia Giannetsou. (Explorer, 2005. ISBN 9607945832), 23 - â Scholz-Hansel, 7

- â Nikolaos M. Panayotakis. The Cretan Period of DomĂ©nicos. (Festschrift In Honor Of Nikos Svoronos, Volume B) (Crete University Press, 1986), 29

- â S. McGarr, St Francis Receiving The Stigmata, August 2005, tuppencworth.ie; J. Romaine, El Greco's Mystical Vision. godspy.com. ; Janet Sethre, "El Greco," The Souls of Venice. (McFarland & Company, 2003. ISBN 0786415738), 91

- â Lambraki-Plaka, 1999, 40-41

P. Katimertzi, El Greco and Cubism - â Harold E. Wethey, Letters to the Editor, Art Bulletin 48 (1): 125-127. (March 1966) via JSTOR. College Art Association, 125-127

- â 10.0 10.1 10.2 Lambraki-Plaka, 1999, 42

- â August L. Mayer, "Notes on the Early El Greco," Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs 74 (430): 28 (January 1939). via JSTOR

- â Scholz-Hansel, 19

- â Richard G. Mann, "Tradition and Originality in El Greco's Work," QUIDDITAS: Journal of the Rocky Mountain Medieval and Renaissance Association 23 (2002): 83-110. 89 Retrieved May 9, 2009.

- â Mary Acton. Learning to Look at Paintings. (Oxford University Press, 1991. ISBN 0521401070), 82

- â Scholz-HĂ€nsel, 20

Tazartes, 31-32 - â 16.0 16.1 16.2 Michael Kimmelmann, El Greco, Bearer Of Many Gifts. The New York Times, October 3, 2003.

- â 17.0 17.1 Scholz-HĂ€nsel, 20

- â 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 Lambraki-Plaka, 1999, 47-49

- â Allan Braham, "Two Notes on El Greco and Michelangelo," Burlington Magazine 108 (759)(June 1966): 307-310. via JSTOR.

Jonathan Jones, The Reluctant Disciple. The Guardian, January 24, 2004. Retrieved May 9, 2009. - â Lizzie Boubli, "Michelangelo and Spain: on the Dissemination of his Draugthmanship," Reactions to the Master, edited by Francis Ames-Lewis and Paul Joannides. (Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2003. ISBN 0754608077), 217

- â 21.0 21.1 21.2 Tazartes, 32

- â 22.0 22.1 22.2 Jonathan Brown and Richard G. Mann. Spanish Paintings of the Fifteenth Through Nineteenth Centuries. (Routledge, 1997. ISBN 0415148898), 42

- â "Greco, El," Encyclopaedia Britannica 2002

Tazartes, 36 - â Jonathan Brown and Richard L. Kagan, "View of Toledo." Studies in the History of Art 11 (1982): 19-30. 19

- â Tazartes, 36

- â 26.0 26.1 Lambraki-Plaka, 1999, 43-44

- â Mark Irving, Arts, etc: How to beat the Spanish Inquisition The Independent on Sunday, May 8, 2004, findarticles.com.

- â Lambraki-Plaka, 1999, 45

- â 29.0 29.1 Scholz-Hansel, 40

- â Lambraki-Plaka, 1999, 45; Jonathan Brown, "El Greco and Toledo," in El Greco of Toledo. (catalogue). (Little Brown, 1982), 98

- â Joseph Pijoan, "El Greco - A Spaniard." Art Bulletin 12 (1) (March 1930): 12-19. via JSTOR

- â Liisa Berg, El Greco in Toledo. kutri's corner.

- â Brown & Mann, 1997, 42; JosĂ© Gudiol, "Iconography and Chronology in El Greco's Paintings of St. Francis." Art Bulletin 44 (3)(September 1962): 195-203. 195 (College Art Association) via JSTOR.

- â Tazartes, 49

- â JosĂ© Gudiol. DomĂ©nicos TheotocĂłpoulos, El Greco, 1541-1614. (Viking Press, 1973), 252

- â 36.0 36.1 Tazartes, 61.

- â 37.0 37.1 DomĂ©nicos TheotocĂłpoulos, Encyclopaedia The Helios 1952.

- â Scholz-Hansel, 81

- â Hispanic Society of America, El Greco in the Collection of the Hispanic Society of America. (Printed by order of the trustees. 1927), 35-36; Tazartes, 2005, 67

- â Fernando Marias and GarcĂa AgustĂn Bustamante. Las Ideas ArtĂsticas de El Greco. (CĂĄtedra, 1981. ISBN 8437602637), 80 (in Spanish).

- â 41.0 41.1 A. E. Landon, Reincarnation Magazine 1925. (reprint ed. Kessinger Publishing, 2003. ISBN 0766137759), 330

- â J.A. Lopera, El Greco: From Crete to Toledo, 20-21

- â J. Brown, El Greco and Toledo, 110; Fernando Marias. "El Greco's Artistic Thought," El Greco, Identity and Transformation, edited by Alvarez Lopera. (Skira, 1999. ISBN 8881184745), 183-184.

- â J. Brown, El Greco and Toledo, 110

- â N. Penny, At the National Gallery

- â 46.0 46.1 Lambraki-Plaka, 57-59

- â J. Brown, El Greco and Toledo, 136

- â Marias and Bustamante, 52

- â Nicos Hadjinikolaou, "Inequalities in the work of TheotocĂłpoulos and the Problems of their Interpretation," in Meanings of the Image, edited by Nicos Hadjinicolaou (in Greek). (University of Crete, 1994. ISBN 9607309650), 89-133.

- â The Metropolitan Museum of Art, El Greco

- â Robert Byron, "Greco: The Epilogue to Byzantine Culture." Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs 55 (319)(October 1929): 160-174. via JSTOR; Angelo Procopiou, "El Greco and Cretan Painting." Burlington Magazine 94(588) (March 1952): 74, 76-80.

- â Manuel BartolomĂ© CossĂo. El Greco. (in Spanish). (Madrid: Victoriano SuĂĄrez, 1908), 501-512.

- â 53.0 53.1 53.2 53.3 53.4 Cormack-Vassilaki, The Baptism of Christ

- â Robert Meredith Helm. "The Neoplatonic Tradition in the Art of El Greco," Neoplatonism and Western Aesthetics, edited by Aphrodite Alexandrakis and Nicholas J. Moutafakis. (SUNY Press, 2001. ISBN 0791452794), 93-94; August L. Mayer, "El Greco-An Oriental Artist." Art Bulletin 11 (2)(June 1929):146-152. 146. via JSTOR.

- â Marina Lambraki-Plaka, "El Greco, the Puzzle." DomĂ©nicos TheotocĂłpoulos today. To Vima. (19 April 1987), 19

- â Cyril Mango and Elizabeth Jeffreys. "Towards a Franco-Greek Culture," The Oxford History of Byzantium. (Oxford University Press, 2002. ISBN 0198140983), 305

- â Nicos Hadjinikolaou, "DomĂ©nicos TheotocĂłpoulos, 450 Years from his Birth." El Greco of Crete. (proceedings), edited by Nicos Hadjinicolaou. (Herakleion, 1990), 92.

- â David Davies, "The Influence of Neo-Platonism on the Art of El Greco," El Greco of Crete. (proceedings), edited by Nicos Hadjinicolaou. (Herakleion, 1990), 20, etc.; Davies, "The Byzantine Legacy in the Art of El Greco," El Greco of Crete. (proceedings), edited by Nicos Hadjinicolaou. (Herakleion, 1990), 425-445.

- â JosĂ© Ălvarez Lopera, El Greco: From Crete to Toledo, 18-19

- â Enriquetta Harris, "A Decorative Scheme by El Greco." Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs 72 (421) (April 1938): 154. via JSTOR.

- â Liane Lefaivre and Alexander Tzonis, The Emergence of Modern Architecture, 165

- â Illescas Allardyce, Historic Shrines of Spain. (1912). (reprint ed. Kessinger Pub., 2003. ISBN 0766136213), 174.

- â 63.0 63.1 Lefaivre-Tzonis, The Emergence of Modern Architecture, 164

- â 64.0 64.1 64.2 Lambraki-Plaka, 1999, 49

- â Brown and Mann, 43; Efi Foundoulaki. From El Greco to CĂ©zanne, (catalogue). (Athens: National Gallery-Alexandros Soutsos Museum, 1992), 100-101

- â 66.0 66.1 66.2 Foundoulaki, 100-101.

- â 67.0 67.1 67.2 John Russel, Seeing The Art Of El Greco As Never Before The New York Times, July 18, 1982, Retrieved May 12, 2009.

- â Brown and Mann, 43; Foundoulaki, 103.

- â J. J. Sheehan. "Critiques of a Museum Culture," Museums in the German Art World. (Oxford University Press, USA, 2000. ISBN 0195135725), 150.

- â Julius Meier-Graefe. The Spanish Journey, translated from German by J. Holroyd-Reece. (London: Jonathan Cape, 1926), 458.

- â Tazartes, 68-69

- â Lambraki-Plaka, 1999, 59; Athens News Agency, Greece buys unique El Greco for 1.2 million dollars Hellenic Resources Institute, 09/06/1995. hri.org. (in English) Retrieved May 12, 2009.

- â Efi Foundoulaki, From El Greco to CĂ©zanne, 113

- â Harold E. Wethey. El Greco and his School. Volume II. (Princeton University Press, 1962), 55.

- â E. Foundoulaki, From El Greco to CĂ©zanne, 103

- â E. Foundoulaki, From El Greco to CĂ©zanne, 105-106

- â Jonathan Brown, "El Greco, the Man and the Myth," in El Greco of Toledo (catalogue). (Boston: Little Brown, 1982), 28

- â Lambraki-Plaka, From El Greco to CĂ©zanne, 15

- â C. B. Horsley, Exhibition: The Shock of the Old. Metropolitan Museum of Art, (New York), October 7, 2003 to January 11, 2004 and The National Gallery, (London), February 11 to May 23, 2004. Retrieved May 12, 2009.

- â Ron Johnson, "Picasso's Demoiselles d'Avignon and the Theatre of the Absurd." Arts Magazine V (2) (October 1980): 102-113Â ; John Richardson, "Picasso's Apocalyptic Whorehouse." The New York Review of Books 34(7): 40-47. (April 23, 1987). The Burlington Magazine Publications, Ltd. 40-47

- â D. de la SouchĂšre, Picasso Ă Antibes, 15

- â E. Foundoulaki, From El Greco to CĂ©zanne, 111

* D. de la SouchĂšre, Picasso Ă Antibes, 15 - â Foundoulaki, 111

- â E. Foundoulaki, Reading El Greco through Manet, 40-47

- â Wassily Kandinsky and Marc Franz. L'Almanach du "Blaue Reiter". (Paris: Klincksieck, 1987. ISBN 2252025670). (in French), 75-76.

- â James T. Valliere, "The El Greco Influence on Jackson Pollock's Early Works." Art Journal 24(1): 6-9. (Autumn 1964) [12]. via JSTOR. College Art Association.

- â H. A. Harrison, Getting in Touch With That Inner El Greco The New York Times. Retrieved May 12, 2009.

- â F. Naqvi-Peters, The Experience of El Greco, 345

- â Rassias-Alaxiou-Bien, Demotic Greek II, 200; Alan Sanders and Richard Kearney. The Wake of Imagination: Toward a Postmodern Culture. (Routledge (UK), 1998. ISBN 0415119502), Chapter: "Changing Faces," 10.

- â Film on Life of Painter El Greco Planned. Athens News agency.

- â Tazartes, 25

- â Rodolfo Palluchini, "Some Early Works by El Greco," Burlington Magazine 90 (542)(May 1948): 130-135, 137. via JSTOR.

- â Cormack-Vassilaki, The Baptism of Christ: new light on early El Greco. ; Tazartes, 70

- â E. Arslan, Cronisteria del Greco Madonnero, 213-231

- â D. Alberge, Collector Is Vindicated as Icon is Hailed as El Greco. Timesonline, August 24, 2006. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

- â 96.0 96.1 H.E. Wethey, "El Greco in Romeand the Portrait of Vincenzo Anastagi." Studies in the History of Art 13 (1984): 171-178.

- â Richard G. Mann, "Tradition and Originality in El Greco's Work," Journal of the Rocky Mountain 23 (2002):83-110. 102. The Medieval and Renaissance Association.

- â Epimetheus and Pandora, Web Gallery of Art; X. de Salas, "The Velazquez Exhibition in Madrid." Burlington Magazine 103(695) (February 1961):54-57.

- â El Greco Drawings Could Fetch ÂŁ400,000, The Guardian(UK)Â ; Study for St John the Evangelist and an Angel, Web Gallery of Art.

- â Pandelis Prevelakis. TheotocĂłpoulos-Biography. (1947), 47 (in Greek)

- â Lambraki-Plaka, 1999, 40-41; Scholz-Hansel, 7; Tazartes, 23

- â Joanna Kakissis, A Cretan Village that was the Painter's Birthplace Globe, March 6, 2005, boston.com. Retrieved May 12, 2009.

- â K.D. Mertzios, "Selections of the Registers of the Cretan Notary Michael Maras (1538-1578)." Cretan Chronicles 2 (15-16) (1961-1962): 55-71. (in Greek).

- â 104.0 104.1 Maria Constantoudaki, "TheotocĂłpoulos from Candia to Venice." (in Greek). Bulletin of the Christian Archeological Society 8 (period IV)(1975-1976): 55-71, 71.

- â Janet Sethre, "El Greco," in The Souls of Venice. (McFarland & Company, 2003. ISBN 0786415738), 90.

- â Scholz-HĂ€nsel, 92

- â Robert Engasse and Jonathan Brown, "Artistic Practice - El Greco versus the Hospital of Charity, Illescas," Italian and Spanish Art, 1600-1750. (Northwestern University Press, 1992. ISBN 0810110652), 205.

- â F. de S.R. FernĂĄdez, De la Vida del Greco, 172-184

- â Tazartes, 56, 61

- â ThĂ©ophil Gautier, "Chapitre X," Voyage en Espagne. (in French). (Paris: Gallimard-Jeunesse, 1981. ISBN 2070372952), 217.

- â R.M. Helm, The Neoplatonic Tradition in the Art of El Greco, 93-94; Tazartes, 68-69

- â Ian Grierson, "Who am Eye," The Eye Book. (Liverpool University Press, 2000. ISBN 0853237557), 115

- â Stuart Anstis, "Was El Greco Astigmatic," Leonardo 35 (2)(2002): 208

- â John Armstrong. "The Fine Arts - End of the Golden Age," Spain: The Root and the Flower. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985. ISBN 0520051335), 216.

Bibliography

Printed sources (books and articles)

- Acton, Mary. Learning to Look at Paintings. Oxford University Press, 1991. ISBN 0521401070.

- Allardyce, Isabel. Our Lady of Charity, at Illescas, Historic Shrines of Spain, (1912). reprint ed. Kessinger Pub., 2003. ISBN 0766136213.

- Ălvarez Lopera, JosĂ©,"El Greco: From Crete to Toledo (translated in Greek by Sofia Giannetsou)," in M. Tazartes' "El Greco." Explorer, 2005. ISBN 9607945832.

- Anstis, Stuart, "Was El Greco Astigmatic?" Leonardo 35 (2)(2002): 208.

- Armstrong, John. "The Fine Arts - End of the Golden Age," Spain: The Root and the Flower. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985. ISBN 0520051335.

- Arslan, Edoardo, "Cronisteria del Greco Madonnero." Commentari xv (5)(1964): 213-231.

- Boubli, Lizzie. "Michelangelo and Spain: on the Dissemination of his Draugthmanship," Reactions to the Master, edited by Francis Ames-Lewis and Paul Joannides. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2003. ISBN 0754608077.

- Braham, Allan, "Two Notes on El Greco and Michelangelo." Burlington Magazine 108 (759)(June 1966): 307-310. via JSTOR.

- Brown, Jonathan, "El Greco and Toledo," and "El Greco, the Man and the Myth," in El Greco of Toledo (catalogue). Little Brown, 1982. ASIN B-000H4-58C-Y.

- Brown Jonathan, and Richard L. Kagan, "View of Toledo." Studies in the History of Art 11 (1982): 19-30.

- Brown, Jonathan, and Richard G. Mann, "Tone," Spanish Paintings of the Fifteenth Through Nineteenth Centuries. Routledge, 1997. ISBN 0415148898.

- Byron, Robert, "Greco: The Epilogue to Byzantine Culture." Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs 55 (319)(October 1929): 160-174.

- Constantoudaki, Maria, "D. TheotocĂłpoulos, from Candia to Venice." (in Greek). Bulletin of the Christian Archeological Society 8 (period IV)(1975-1976): 55-71.

- CossĂo, Manuel BartolomĂ© (1908). El Greco. (in Spanish). Madrid: Victoriano SuĂĄrez.

- Crow, John Armstrong. "The Fine Arts - End of the Golden Age," Spain: The Root and the Flower. University of California Press, 1985. ISBN 0520051335.

- Davies, David, "The Byzantine Legacy in the Art of El Greco," El Greco of Crete. (proceedings), edited by Nicos Hadjinicolaou. Herakleion, 1990.

- __________. "The Influence of Christian Neo-Platonism on the Art of El Greco," El Greco of Crete. (proceedings), edited by Nicos Hadjinicolaou. Herakleion, 1990.

- Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2002). "Greco, El."

- Encyclopaedia The Helios. "Theotocópoulos, Doménicos." 1952.

- Engass Robert, and Jonathan Brown, "Artistic Practice - El Greco versus the Hospital of Charity, Illescas," Italian and Spanish Art, 1600-1750. Northwestern University Press, 1992. ISBN 0810110652.

- Fernådez, Francisco de San Romån, "De la VIda del Greco - Nueva Serie de Documentos Inéditos." Archivo Español del Arte y Arqueologia 8 (1927): 172-184.

- Foundoulaki, Efi, "From El Greco to CĂ©zanne," From El Greco to CĂ©zanne (catalogue). National Gallery-Alexandros Soutsos Museum, (1992).

- __________. "Reading El Greco through Manet." (in Greek). Anti (445) (24 August 1990): 40-47.

- Gautier, Théophil, "Chapitre X," Voyage en Espagne. (in French). Gallimard-Jeunesse, 1981. ISBN 2070372952.

- Grierson, Ian, "Who am Eye," The Eye Book. Liverpool University Press, 2000. ISBN 0853237557.

- Griffith, William. "El Greco," Great Painters and Their Famous Bible Pictures. reprint ed. Kessinger Publishing, 2005. ISBN 1417906081.

- Gudiol, José. Doménicos Theotocópoulos, El Greco, 1541-1614. Viking Press, 1973. ASIN B-0006C-8T6-E.

- __________. Iconography and Chronology in El Greco's Paintings of St. Francis

Art Bulletin 44 (3)(September 1962): 195-203. via JSTOR. College Art Association

- Hadjinicolaou, Nicos. "Doménicos Theotocópoulos, 450 Years from his Birth." El Greco of Crete. (proceedings), edited by Nicos Hadjinicolaou. Herakleion, 1990.

- __________, "Inequalities in the work of TheotocĂłpoulos and the Problems of their Interpretation," Meanings of the Image, edited by Nicos Hadjinicolaou (in Greek). University of Crete, 1994. ISBN 9607309650.

- Harris, Enriquetta, (April 1938). "A Decorative Scheme by El Greco." Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs 72 (421): 154-155+157-159+162-164.

- Helm, Robert Meredith. "The Neoplatonic Tradition in the Art of El Greco," Neoplatonism and Western Aesthetics, edited by Aphrodite Alexandrakis and Nicholas J. Moutafakis. SUNY Press, 2001. ISBN 0791452794.

- Hispanic Society of America. El Greco in the Collection of the Hispanic Society of America. Printed by order of the trustees. 1927.

- Johnson, Ron, "Picasso's Demoiselles d'Avignon and the Theatre of the Absurd." Arts Magazine V (2) (October 1980): 102-113.

- Kandinsky, Wassily, and Marc Franz. L'Almanach du "Blaue Reiter". Paris: Klincksieck, 1987. ISBN 2252025670. (in French)

- Lambraki-Plaka, Marina. El Greco-The Greek. Kastaniotis, 1999. ISBN 9600325448.

- __________. "El Greco, the Puzzle." Doménicos Theotocópoulos today. To Vima. (19 April 1987).

- __________. "From El Greco to CĂ©zanne (An "Imaginary Museum" with Masterpieces of Three Centuries)," From El Greco to CĂ©zanne (catalogue). National Gallery-Alexandros Soutsos Museum. (1992).

- Landon, A. E. Reincarnation Magazine 1925. reprint ed. Kessinger Publishing, 2003. ISBN 0766137759.

- Lefaivre Liane, ed. Emergence of Modern Architecture: A Documentary History, from 1000 to 1800. Routledge, 2004. ISBN 0415260248.

- __________. and Alexander Tzonis, "El Greco (Domenico Theotocopoulos)," El Greco-The Greek. Routledge (UK), 2003. ISBN 0415260256.

- Lopera, JosĂ© Ălvarez

- Mango, Cyril, and Elizabeth Jeffreys, "Towards a Franco-Greek Culture," The Oxford History of Byzantium. Oxford University Press, 2002. ISBN 0198140983.

- Mann, Richard G., "Tradition and Originality in El Greco's Work." Journal of the Rocky Mountain 23 (2002):83-110. [1]. The Medieval and Renaissance Association.

- Marias, Fernando. "El Greco's Artistic Thought," El Greco, Identity and Transformation, edited by Alvarez Lopera. Skira, 1999. ISBN 8881184745.

- __________. and Bustamante GarcĂa AgustĂn. Las Ideas ArtĂsticas de El Greco. (in Spanish). CĂĄtedra, 1981. ISBN 8437602637.

- Mayer, August L., "El Greco - An Oriental Artist." Art Bulletin 11 (2):146-152. (June 1929). College Art Association.

- __________, "Notes on the Early El Greco." Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs 74 (430): 28-29+32-33. (January 1939). The Burlington Magazine' Publications, Ltd.

- Meier-Graefe, Julius. (1926). The Spanish Journey, translated form German by J. Holroyd-Reece. London: Jonathan Cape.

- Mertzios, K. D. "Selections of the Registers of the Cretan Notary Michael Maras (1538-1578)." (in Greek). Cretan Chronicles 2 (15-16): 55-71. (1961-1962).

- Nagvi-Peters, Fatima, "A Turning Point in Rilke's Evolution: The Experience of El Greco." Germanic Review 72 (22 September 1997) [2]. highbeam.com.

- Pallucchini, Rodolfo, "Some Early Works by El Greco." Burlington Magazine 90 (542): 130-135, 137. (May 1948) The Burlington Magazine Publications, Ltd.

- Panayotakis, Nikolaos M. The Cretan Period of the Life of Doménicos Theotocópoulos, Festschrift In Honor Of Nikos Svoronos, Volume B. Crete University Press, 1986.

- Pijoan, Joseph, "El Greco - A Spaniard." Art Bulletin 12 (1) (March 1930): 12-19.

- Procopiou, Angelo, "El Greco and Cretan Painting." Burlington Magazine 94(588):74, 76-80. (March 1952).

- Rassias, John, Christos Alexiou, and Peter Bien. Demotic Greek II: The Flying Telephone Booth. UPNE, 1982. ISBN 087451208-5. chapter: Greco.

- Richardson, John, "Picasso's Apocalyptic Whorehouse." The New York Review of Books 34(7): 40-47. (23 April 1987). The Burlington Magazine Publications, Ltd.

- de Salas, X., "The Velazquez Exhibition in Madrid." Burlington Magazine 103(695):54-57.(February 1961)[3].

- Sanders, Alan, and Richard Kearney. The Wake of Imagination: Toward a Postmodern Culture. Routledge (UK), 1998. ISBN 0415119502. Chapter: "Changing Faces."

- Scholz-Hansel, Michael. El Greco. Taschen, 1986. ISBN 3822831719.

- Sethre, Janet, "El Greco," The Souls of Venice. McFarland & Company, 2003. ISBN 0786415738.

- Sheehanl, J.J. "Critiques of a Museum Culture," Museums in the German Art World. Oxford University Press, USA, 2000. ISBN 0195135725.

- SouchĂšre de la, Dor. Picasso Ă Antibes. (in French). Paris: Fernan Hazan, 1960.

- Tazartes, Mauricia. El Greco, translated in Greek by Sofia Giannetsou. Explorer, 2005. ISBN 9607945832.

- Valliere, James T., "The El Greco Influence on Jackson Pollock's Early Works." Art Journal 24(1): 6-9. (Autumn 1964). College Art Association.

- Wethey, Harold E. El Greco and his School. (Volume II) Princeton University Press, 1962. ASIN B-0007D-NZV-6

- __________. "El Greco in Rome and the Portrait of Vincenzo Anastagi." Studies in the History of Art 13 (1984): 171-178.

- __________. Letter to the Editor. Art Bulletin 48 (1): 125-127. (March 1966) College Art Association.

On-line sources

- Alberge, Dalya, Collector Is Vindicated as Icon Is Hailed as El Greco Times Online, 2006-08-24. accessdate 2006-12-17

- Berg, Liisa, El Greco in Toledo. accessdate 2006-10-14}

- Cormack, Robin, and Maria Vassilaki The Baptism of Christ New Light on Early El Greco. Apollo Magazine (August 2005). accessdate 2006-12-17

- El Greco. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Department of European Paintings. accessdate 2006-10-17

- El Greco Drawings could fetch ÂŁ400,000. The Guardian, 2002-11-23. accessdate 2006-12-17

- Horsley, Carter B., The Shock of the Old El Greco Museum Exhibition in New York and London. accessdate 2006-10-26

- Irving, Mark, How to Beat the Spanish Inquisition. The Independent on Sunday, 2004-02-08. accessdate 2006-12-17

- Jones, Jonathan, The Reluctant Disciple. The Guardian, 2004-01-24. accessdate 2006-12-18

- Kimmelman, Michael, Art Review; El Greco, Bearer Of Many Gifts. The New York Times, 2003-10-03. accessdate 2006-12-17

- Mayer, August L., "Notes on the Early El Greco," Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs 74 (430): 28 (January 1939). via JSTOR

- McGarr, Simon, St Francis Receiving The Stigmata. accessdate 2006-11-24

- Penny, Nicholas, At the National Gallery. accessdate 2006-10-25

- The Guardian, Revelations - The first Major British Retrospective of El Greco Has the Power of a Hand Grenade. 2004-02-10, accessdate 2006-12-17

- Romaine, James, El Greco's Mystical Vision. accessdate 2006-11-24

- Russel, John, The New York Times Art View; Seeing the Art of El Greco as never before. 1982-07-18, accessdate 2006-12-17

- Web Gallery of Art, Works and Biography of El Greco. accessdate 2006-10-25

Further reading

- Aznar, José Camón. Dominico Greco. Madrid. 1950.

- Davies, David, and John H. Elliott, Eds., et al. El Greco (catalogue). London: National Gallery, 2006. ISBN 1857099389.

- Marias, Fernando. El Greco in Toledo. Scala Publishers, 2005. ISBN 1857592107.

External links

All links retrieved February 12, 2024.

- El Greco Biography and Tour. National Gallery of Art Washington, DC.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.