Moors

The Moors were the medieval Muslim inhabitants of al-Andalus (the Iberian Peninsula including present day Spain and Portugal) as well as the Maghreb and western Africa, whose culture is often called Moorish. The word was also used more generally in Europe to refer to anyone of Arab or African descent, sometimes called Blackamoors. The name Moors derives from the ancient tribe of the Maure and their kingdom Mauretania. Andalusia under Muslim rule produced a society in which culture and science and learning flourished. Muslims, Jews, and Christians co-existed in a spirit of mutual tolerance. Scholarship from this period influenced European learning, especially via such people as Roger Bacon and Thomas Aquinas.

The Fall of Granada in 1492 saw the end of the Muslim presence in Andalusia. This event has had a global impact, giving impetus to the Spanish conquest of the New World inspired by their triumph over the Muslims, which they understood as enjoying God's blessing. What has been described as the Andalusian paradigm suggests that conflict and rivalry is not inevitable for plural societies, that people of different faiths can co-existence and enjoy creative intellectual and cultural exchange.

Etymology

"Moor" comes from the Greek word mauros (plural mauroi), meaning "black" or "very dark," which in Latin became Mauro (plural Mauri). The Latin word for black was not mauro but niger, or fusco for âvery dark.â In some but certainly not all, cases, Moors were described as fuscus. Due to the relevance of this population in the Iberian peninsula during the Middle Ages, this term may have entered Englishâand other European languages less exposed to this groupâvia its Spanish cognate moro. It is important to emphasize that the Greeks and Romans clearly saw black-skinned Africans as a separate group of people. This was highlighted in the Greek word Aithiops, meaning, literally, a dark-skinned person. The word was applied only to some Ethiopians and to certain other dark and black-skinned Africans. With a few poetical exceptions, it was not applied to Egyptians or to inhabitants of northwest Africa, such as Carthaginians, Numidians, or Moors. The understanding of Egyptians as distinct from their southern neighbors is also clear in the ancient iconographic and written evidence. The evidence also shows that the physical type of the Ethiopian inhabitants of the Nile Valley south of Egypt, not the Egyptians, most clearly resembled that of Africans and peoples of African descent described in the modern world as Negroes or blacks. [1]

In the Arab literature there is little mention of the word Moor. Rather, anthropologist Dana Reynolds contends that the Berbers emerged as the result of admixture between non-African populations who moved into the Maghrib during the second millennium B.C.E. and the more ancient African indigenous inhabitants. This would account for the variance noted among the Berbers even in ancient times. According to Roman documents, among the Berbers were the "black Gaetuli and black-skinned Asphodelodes." â (Courtesy of Dana Reynolds, Runoko Rashidi and Wayne Chandler)

Saint Isidore of Seville, who was born in 560 C.E. and died in April 636 C.E., wrote that Maurus means "black" in Greek. In the late 1400s, the Italian Roberto di San Severino in his writings clearly distinguishes between Moors and Arabs. In describing his journey to Mount Sinai, san Severino writes on the observance of the Muslim month of Ramadan, stating "Their 'Ramatana' lasts a month, and every day they fast. They neither eat nor drink until the evening, that is until the hour of the stars; and this custom is followed by the Moors as well as the Arabs."

In the eighteenth century English usage of the term "Moor" began to refer specifically to African Muslims, but especially to any person who speaks one of the Hassaniya dialects. This language, in its purest form, draws heavily from the original Yemeni Arabic spoken by the Bani Hassan tribe, which invaded northwest Africa during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

In Spanish usage, "Moro" (Moor) came to have an even broader usage, to mean "Muslims" in general (just as "Rumi," "from the Eastern Roman Empire," came to mean "Christian" in many Arabic dialects); thus the Moros of Mindanao in the Spanish-speaking Philippines, and the Moriscos of Granada. Moro is also used to describe all things dark as in "Moor," "moreno" and it has led to many European surnames such as "Moore," "De Muaro," and so on. The Milanese Duke Ludovico Il Moro was so-called because of his swarthy complexion.

Until the early twentieth century "Moor" was often used by Western geographers to refer to "mixed" Arab-Berber North Africans, especially of the towns, as distinct from supposedly more pure-blooded Arabs and Berbers; thus the 1911 EncyclopĂŚdia Britannica defines "Moor" as "the name which, as at present used, is loosely applied to any native of Morocco, but in its stricter sense only to the townsmen of mixed descent. In this sense it is also used of the Muslim townsmen in the other Barbary states." But even then, it recognized that "the term Moors has no real ethnological value."

History

In 711 C.E., the Moors invaded Visigoth, Christian Hispania. Under their leader, an African Berber general named Tariq ibn-Ziyad, they brought most of the Iberian Peninsula under Islamic rule in an eight-year campaign. They attempted to move northeast across the Pyrenees Mountains but were defeated by the Frank, Charles Martel, at the Battle of Tours in 732 C.E. The Moorish state suffered civil conflict around 750 C.E. The Moors ruled in the Iberian peninsula, except for areas in the northwest (such as Asturias, where they were stopped at the battle of Covadonga) and the largely Basque regions in the Pyrenees, and in North Africa for several decades. Though the number of "Moors" remained small, they gained large numbers of converts. The Moorâs invasion of Spain, from the point of view of Christians in Europe, was always regarded as an act of aggression. Indeed, it was part of the outward expansion of the Islamic world that was informed by the conviction that the whole world should be subject to Islamic rule and to the divine law of Islam. However, the actual story of the invasion is more complex. The Visigoth King, Roderic had raped the daughter of one of his Counts, Julian who, in secret, approached the Moors and pledged support in the event of an invasion. Jewish advisers also accompanied the invading force.[2] There is also evidence that some territory was gained peacefully through treaties that enlisted the "cooperation of local administrators and inhabitants." Constable reproduces a "Muslim-Christian Treaty" of 713 in which the ruler of Tudmir and his people are promised protection and religious freedom in return for an annual tribute and loyalty to the Sultan.[3]

The Umayyadâs sultanate (756 - 929 C.E.) and later caliphate of Cordoba (929 - 1031 C.E.) in Andalusia (modern Spain) rivaled the Abbasids at a time when the Fatimids also challenged their supremacy, and provides an example of an Islamic society where scholarship (which was already patronized by the early Damascus based Umayyads) and inter-community exchange flourished.

Christian states based in the north and west slowly extended their power over the rest of Iberia. The Kingdom of Asturias, Navarre, Galicia, LeĂłn, Portugal, AragĂłn, Catalonia or Marca Hispanica, and Castile started a steady process of expansion and internal consolidation during the next several centuries under the flag of Reconquista.

The initial rule of the Moors in the Iberian peninsula under the Caliphate of Cordoba is generally regarded as tolerant in its acceptance of Christians, Muslims and Jews living in the same territories, though Jews were expelled in various periods and Christians relegated to 2nd class status under Muslims. The Caliphate of CĂłrdoba collapsed in 1031 and the Islamic territory in Iberia came to be ruled by North African Moors of the Almoravid Dynasty. This second stage started an era of Moors rulers guided by orthodox Islam leaving behind the more tolerant practices of the past. It was during this period that the great Jewish scholar Moses Maimonides was forced to leave Andalusia, although he found refuge in another part of the Muslim world. Even in the intolerant Almohads (who seized power in 1145 C.E.) threatened Jews with death or expulsion if they did not convert but later entered into alliances with Christian rulers and even encouraged Christian to settle in Fez. With the fall of the Ummayad caliphate, the period of small city-states, or taifa, began.

Moorish Iberia excelled in city planning; the sophistication of their cities was astonishing. According to one historian,

Cordoba had 471 mosques and 300 public baths ... the number of houses of the great and noble were 63,000 and 200,077 of the common people. There were ... upwards of 80,000 shops. Water from the mountain was distributed through every corner and quarter of the city by means of leaden pipes into basins of different shapes, made of the purest gold, the finest silver, or plated brass as well into vast lakes, curios tanks, amazing reservoirs and fountains of Grecian marble.[4]

The houses of Cordoba were air conditioned in the summer by "ingeniously arranged draughts of fresh air drawn from the garden over beds of flowers, chosen for their perfume, warmed in winter by hot air conveyed through pipes bedded in the walls." This list of impressive works includes lamp posts that lit their streets at night to grand palaces, such as the one called Azzahra with its 15,000 doors.[4] Without a doubt, during the height of the Caliphate of CĂłrdoba, the city of CĂłrdoba proper was one of the major capitals in Europe and probably the most cosmopolitan city of its time.

In 1212 C.E., a coalition of Christian kings under the leadership of Alfonso VIII of Castile drove the Muslims from Central Iberia. However, the Moorish Kingdom of Granada thrived for three more centuries in the southern Iberian peninsula. This kingdom is known in modern time for architectural gems such as the Alhambra. On January 2, 1492, the leader of the last Muslim stronghold in Granada surrendered to armies of a recently united Christian Spain (after the marriage of Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile). The remaining Muslims were forced to leave Iberia or convert to Christianity. In 1480, Isabella and Ferdinand instituted the Inquisition in Spain, as one of many changes to the role of the church instituted by the monarchs. The Inquisition was aimed mostly at Jews and Muslims who had overtly converted to Christianity but were thought to be practicing their faiths secretlyâknown respectively as morranos and moriscosâas well as at heretics who rejected Roman Catholic orthodoxy, including alumbras who practiced a kind of mysticism or spiritualism. They were an important portion of the peasants in some territories, like Aragon, Valencia or Andalusia, until their systematic expulsion in the years from 1609 to 1614. Henri Lapeyre has estimated that this affected 300,000 out of a total of 8 million inhabitants of the peninsula at the time.

In the meantime, the tide of Islam had rolled not just westward to Iberia, but also eastward, through India, the Malayan peninsula, and Indonesia up to Mindanao-âone of the major islands of an archipelago which the Spanish had reached during their voyages westward from the New World. By 1521, the ships of Magellan had themselves reached that island archipelago, which they named the Philippines, after Philip II of Spain. On Mindanao, the Spanish also named these kris-bearing people as Moros, or 'Moors'. This identification of Islamic people as Moros persists in the modern Spanish language spoken in Spain.

Culture

CĂłrdobaâs library was one of the largest in Europe, possessing some four hundred thousand volumes. The catalogues alone are said to have consisted of 44 volumes. [5] The Libraries and Academies of Cordoba and Toledo would attract scholars from Europe as well as from elsewhere in the Muslim world. Works of philosophy, science, medicine were translated into Latin, some of which were Arabic versions of Greek works but many were written by Muslim scholars. What developed in Andalusia has been described as convivencia ( fruitful coexistence) although in the earliest period, some Christians adopted a very negative opinion of Islam.

Early Christian opposition

During the early Moorish period in Spain a group of Christians, looking at their Bibles, came to the conclusion that Muhammad was the beast of Revelation 13 (they thought he had been born in the year 666) and the Little Horn of Daniel 7: 8. From this they calculated that Islam would flourish for three and a half periods of 70 years each, that is, for 245 years then the Day of Judgement would dawn. Bishop Eulogius of Toledo (d. 859) and his friend, Alvarus, encouraged some 48 Christians (between 850 and 859) to publicly insult Muhammad and Islam so that they attracted the death sentence and were martyred (known as the martyrs of Cordoba). They stood outside Mosques or attended Islamic courts and shouted out statements that they knew were offensive to Muslims, such as that Muhammad was an imposter, a false prophet who had composed the Qurâan and was a lecher who lusted after women. Much of this is gleaned from a brief Life of Muhammad, the Istoria de Mahomet, known to be in circulation in Spain at the time.[6] Written in Latin, they preferred this to anything in Arabic: "They were fleeing from the embrace of Islam: it is not likely they would turn to Islam to understand what it was they were fleeing from."[7] They believed that their voluntary martyrdom would hasten the coming of the End.

The Jewish Experience

The Jews called Andalus Sefarad. O'Shea comments that after their experience under the Visigoths, what followed under Muslim rule was "three uninterrupted centuries of peace."[8] The Sephardim or Sephardic Jews trace their descent from the Jews of this period. Jewish scholarship flourished alongside the Muslim academies.

Mutually Fruitful Co-existence

While the Muslim conquest of much of Spain and memory of the Battle of Tours (732) infuriated Christians in Europe, fueling animosity towards the Saracen as the Godless enemy, relations between Christians and Muslim in Andalusia became increasingly cordial. Some inter-marriage occurred, as between Alfonso IV of Castille (1065-1109) and Princess Zaida, âwhose father was the most powerful among the rulers of the taifa statesâ, the remaining Muslim territories in Spain [9] Christian scholars visiting Spain from France and from England eagerly translated Arabic versions of Greek classics as well as the works of Muslim philosophers into Latin, so that Muslims such as Ibn Rushd and Ibn Sina not only acquired Latin names (Averroes) and (Avicenna) but would be cited by such eminent Christian thinkers as Aquinas (1225-1274) with respect. Scholasticism in Europe is generally said to have been heavily influenced by Muslim philosophy, so much so that one of the main schools was known as Averroism. It drew heavily on Averroesâ commentaries on Aristotle. Thomas Aquinas explored the same issues as had the Muslim philosophers and, open to hearing Godâs voice through a variety of sources, saw himself and Muslims as occupying the same intellectual world of rational discourse. Muslims, he believed, could be won for Christ through reasoned argument, even with love. Such men as Peter the Venerable (1092-1156), Ramon Lull (1234-1316) and Roger Bacon (1220-1292) all believed that âreasonâ not force was the correct modus operandi for Christians in relationship with Islam. Such legends as the Story of Roland and El Cidâs chronicle still depicted Muslims as idolaters but more accurate information was now becoming available. Tradition turned El Cid (d. 1099) into a Christian crusader, but he actually worked for Muslims as well as for Christians, crossing the frontier between the various states.[10] Andalusia produced, among others, Ibn Rushd, Ibn Hazm and Ibn Tufail while Ibn Khaldun worked for sometime for the Sultan of Granada. Links were especially strong between the Academies of Andalusia and the University of Paris.

Peter the Venerable commissioned the first Latin rendition of the Qurâan, which, completed in 1143 has been described as âa landmark ⌠for the first timeâ, Europeans had âan instrument for the serious study of Islamâ [11]. It remained the standard rendering until the sixteenth century. The translator was an Englishman, Robert of Ketton (1110-1160) who had traveled in Palestine and appears to have settled in Spain in order to work as a translator. He was also an Archdeacon. Kettonâs Qurâan was glossed with hostile footnotes,[12] but it at least gave Christians access to the complete scripture, rather than to selected sections. Lull, Bacon and others called for Arabic chairs at Paris and Oxford. Lullâs own conviction that Muslims should be reasoned with did not preclude him from using some harsh language when addressing Muslims. A tertiary Franciscan, Lull was twice deported from Tunisia. On a third visit to the Muslim world he ended up defending the Trinity by publicly abusing Islam, âthe law of the Christians is holy and trueâ, he said, âand the sect of the Moors is false and wrongâ [13]. Stoned by the crowd, he died on shipboard before reaching his native Majorca. Yet the method he bequeathed, ars inveniendi veritatis, the art of finding the truth, was diaological not confrontational and greatly influenced missionary thought. The Crusaders, contemporary with Lull, did not consider evangelism, the attempt to win the hearts of Muslims, as even worth trying, since Muslims were culpable and their death glorified Christ. The essence of crusading was âto slay for Godâs loveâ. Muslims, said one Christian, were not worth disputing with but âwere to be extirpated by fire and the swordâ [14] Lull suggested that instead of conquering the Holy Land by force, Christians ought to do so âby love and prayer and the pouring out of tears and blood.â[15]

The Andalusian Paradigm

Some Muslims regard the Islam of Andalusia to have been too influenced by European ideas to qualify as an authentic version of Islam that Muslims elsewhere and at different times might choose to emulate. Sayyid Qutb, for example, a highly regarded twentieth century Muslim scholar regarded the thought of such philosophers as Ibn Rushd and Ibn Farabi among others as âin essence foreign to the spirit of Islamâ [16]. Others look to the Andalusian paradigm as a model for all Muslims who find themselves living in plural societies. Akbar S. Ahmed describes the Andalusian paradigm as the âideal model of European societyâ. âIf we defineâ, he says, âa civilized society as one which encourages religious and ethnic tolerance, free debate, libraries and colleges, public baths and parks, poetry and architecture, then Muslim Spain is a good exampleâ [17].

Menocal writes of how in Moorish Spain, âJews, Christians and Muslims lived side by side and, despite their intractable differences and enduring hostilities, nourished a complex culture of toleranceâ. This, she suggests, was possible ârooted in the often unconscious acceptance that contradictions â within oneself, as well as within oneâs culture â could be positive and productive.â[18] Friedmann, who provides useful data on the interpretation of Qurâanic material and of relevant hadith on the status of non-Muslims in classical Islamic fiqh (law), points out that Muslims have in practice determined their relationship with Others in terms of either âtolerance or intoleranceâ according to the particular âhistorical circumstances in which the encounter took placeâ. They could choose to stress the verses of friendship alongside such texts as 5: 48 and 109: 6 or they could choose to stress the verses of hostility alongside the sword verses (9: 5; 9: 29).[19] Referring to the Spanish experience of convinencia, Stephen OâShea encourages Christians and Muslims to be less selective in what they choose to remember, and, by âcombining the epochal battles with the eras of convivencia, a clearer picture ⌠one that combats the selective agenda-driven amnesia that has settled over the subject among some of the religious chauvinists of our dayâ may emerge [20]

On the one hand, because they were not a majority, the polity of tolerance may have been pragmatic. On the other hand, there are no few examples in history of minorities ruling over majority populations without any sign of tolerating or of valuing the cultures or the religions of the populace. It is therefore likely that these Muslims had a worldview in which tolerance had a place.

Cultural War

The Andalusian experience has been the subject of cultural war. In the nineteenth century, European scholars claimed that the Muslims had been mere copyists and that what they gave to Europe during the Moorish period was originally borrowed from Europe when much of the legacy of Greek scholarship became Muslim property. Some Muslims claim that European science and technology rests also exclusively on what it borrowed from Muslim scholars, whose work was original and not derivative. Research has shown that much of what the Europeans studies and translated during the Andalusian period was innovative in the fields of medicine, astronomy and navigation, for example.[21] Ahmed suggests a link between Andalusia and the European Renaissance, since Andalusia made 'new thinking' suddenly seem possible [22]

The Fall of Granada and its Global Impact

It is said that Muslims annually mourn the loss of Granada, with its beautiful Alhambra Palace and Gardens. In Spain, annual festivals commemorate the victory. 1492 was a significant year not only for Spain, but globally. It marked the end of Muslim rule in Andalusia, the expulsion of Jews and Christians and the voyage to the Americas of Christopher Columbus. In his diary, Columbus himself placed his "venture in the context of the conquest of Muslim Granada by his patrons." [23] It is argued that the Spaniards success in what they saw as a crusade against Islam provided stimulus and impetus for their conquest of the New World, which they did so "with sword in one hand and Bible in the others fresh from the triumph over the Muslims" [24]

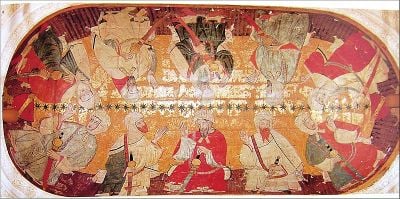

Historical images

The Roman Term "Maur" described the native inhabitants of North Africa west of modern Tunisia. Ancient to modern authors, as well as portraits, show them with a variety of features, just as the modern population contains. This was contrasted with other peoples described as "Aethiopes," or Ethiopians, who lived further south, and Egyptians, or "Aegyptus."

- In portraits that go back to the Old Kingdom, the Egyptians often portrayed their surrounding cultures: Nubians, Libyans and Asiatics. The Libyans were shown with light hair and fair skin.

- In pictures from Islamic Iberia during the seventh to fifteenth centuries, the Moors are portrayed, with some exceptions, looking no different than the native Iberians (distinguished only by their dress). Dark Skinned and East Africans were called âZanj.â

- When the Arabs arrived in North Africa during the seventh century C.E., ending the Greco-Roman period, they also used various terms to describe the Berbers of this region. However, it was the area south of Egypt and the Berber-populations that was called âBilad-al-Sudanâ or âland of the blacks,â not the coastal regions.

- There are also many pictures to be found of Berbers and Moors of obvious sub-Saharan African descent.

To draw any conclusions from these sources in their context (if that is possible) it is necessary to have a thorough knowledge of the period and the iconographic conventions of that period. (See also Berber people Origin.)

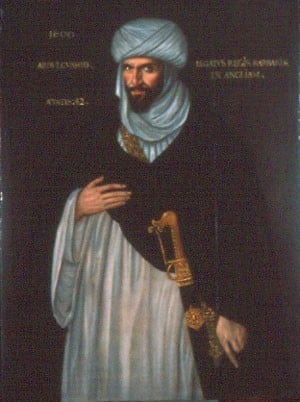

Other Moors in history

- Estevanico, also referred to as "Stephen the Moor," explorer of what is now the southwest (Arizona and New Mexico) of the United States, in the service of Spain.

- Gildo was a Moorish chieftain who instigated a rebellion against the Roman Empire in 398.

- Lusius Quietus was a Roman general and governor of Iudaea in 117 C.E. Originally a Moorish prince, his military ability won him the favor of Emperor Trajan, who even designated him as his successor. During the emperor's Parthian campaign, the numerous Jewish inhabitants of Babylonia revolted and were relentlessly suppressed by Quietus, who was rewarded by being appointed governor of Judea. Restlessness in Palestine caused Trajan to send his favorite, as a legate of consular rank, to Judea, where he continued his sanguinary course.

- Saint Benedict the Moor (1526â1589) Benedict was born of African parents who were slaves on an estate near Messina, Sicily. Though of the lowest social rank, they are typically perceived as noble in heart and mind. As a baby, Benedict was freed by his master and, as a young boy, he showed such a devout and gentle disposition that he was called the "Holy Moor." While working in the fields one day, some neighbors taunted him on account of his race and parentage. His meek demeanor greatly impressed a Franciscan hermit who was passing by and who uttered the prophetic words: "You ridicule a poor Negro now; before long you will hear great things of him." Wishing to join these hermits, Benedict sold his meager belongings and gave the proceeds to the poor and then entered the community. After the death of the superior, Benedict was chosen his successor, though greatly against his will. When Pope Pius IV ordered all hermits to disband or join some Order, Benedict became a Friar Minor of the Observance at Palermo, and was made a cook. He was happy in this work since it enabled him to perform many little acts of kindness toward the others. His brethren were greatly edified by the saintly cook, especially when they saw angels at times helping him in his work. The Chapter of 1578 made him guardian, or superior, of the friary, though he protested that he was not a priest and, in fact, could neither read nor write. He was a model superior, however, and won the esteem and obedience as well as the love of his subjects. As superior, he gave free rein to his love for the poor, and no matter how openhanded he was, the food never seemed to give out. After serving as superior, he was made novice master, and to this difficult post he brought gifts that were evidently infused: he was able to instruct with an amazing knowledge of theology and to read the hearts of others. At his request, he was relieved of his office and again made cook, but he was no longer an obscure Brother, for thousands flocked to the friary, seeking cures or alms or counsel and help. He died after a brief illness, having foretold the hour of his death. His veneration has spread throughout the world, and the Negroes of North America have chosen him their patron. [25]

- Saint Maurice, the Knight of the Holy Lance, is regarded as the greatest patron saint of the Holy Roman Empire. Rumored to be a Roman commander of Egyptian descent, Maurice is said to have gained sainthood after refusing to have his legion massacre a Christian uprising. Honored as early as 460, Saint Maurice has had numerous artworks and structuresâeven a castleâdedicated to him. The existence of nearly three hundred major images of St. Maurice have been catalogued, and even today his veneration is seen within numerous cathedrals in eastern Germany.

- Alessandro de' Medici (July 22, 1510 â January 6, 1537), called "il Moro" ("the Moor") by his contemporaries, was the Duke of Penne and also Duke of Florence (from 1532) and ruler of Florence from 1530 until 1537). Though illegitimate, he was the last of the "senior" branch of the Medici to rule Florence, Italy and the first to be hereditary duke. Historians (such as Christopher Hibbert) believe he had been born to a black serving-woman in the Medici household, identified in documents as Simonetta da Collavechio. The nickname is said to derive from his features. [26] He still has descendants (via his own illegitimate children) among many European royal and noble families.

Moors in popular culture

- In a famous episode of the sitcom Seinfeld, George Costanza engages in a heated argument with a bubble boy over a misspelled Trivial Pursuit answer, which claims that it was the "Moops" who invaded Iberia in 711.

- The title character in William Shakespeare's play Othello is a Moor. The character Aaron the Moor in Titus Andronicus is also a Moor.

- A popular Cuban dish, consisting of white rice and black beans, is named (somewhat facetiously) "Cristianitos y Moros;" the rice representing the fair-skinned Christians, and the beans, the darker-skinned Moors.

- Azeem, Morgan Freeman's character in Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves (1991), was a Moor.

- Sir Morien and Sir Palamedes feature in legendary tales of King Arthur. "Morien, who was dark of face and limb," was said to have saved Sir Gawain on the battlefield.[27]

Notes

- â Frank M. Snowden, Before Color Prejudice: The Ancient View of Blacks (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1991, ISBN 0674063813).

- â ibn 'Abd al-Hakam, "Narrative of the Conquest of al-Andalus," translated by David A. Cohen in Olivia Remie Constable (ed.), Medieval Iberia: Readings from Christian, Muslim and Jewish Sources (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1997, ISBN 0812233336), 32-36.

- â Constable, 37-38.

- â 4.0 4.1 Ivan Van Sertima, Golden Age of the Moor (Transaction Publishers, 1993).

- â MarĂa Rosa Menocal, The Ornament of the World: How Muslims, Jews and Christians Created a Culture of Tolerance in Medieval Spain (Back Bay Books, 2003, ISBN 0316168718), 33.

- â Kenneth B. Wolf, (translator), âA Christian Account of the Life of Muhammadâ in Medieval Iberia: Readings from Christian. Muslim and Jewish Sources, edited by Olivia Remie Constable, (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1997), 48-50.

- â R. W. Southern, Western View of Islam in the Middle Ages Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1962, ISBN 0674950658), 25-26.

- â Stephen OâShea, Sea of Faith (New York: Walker, 2006, ISBN 0802714986), 84.

- â Richard Fletcher, The Cross and the Crescent: Christianity and Islam from Muhammad to the Reformation (Viking, 2004, ISBN 9780670032716), 116.

- â Fletcher, 89.

- â Southern, 37.

- â Fletcher, 128-129.

- â Norman Daniel, Islam and the West: The Making of an Image (Oxford: OneWorld, 2001, ISBN 1851681299), 141.

- â Daniel, 136.

- â cited by William Henry Temple Gairdner, The Rebuke of Islam (Wentworth Press, 2019, ISBN ISBN 978-0526398485), 179.

- â Sayyid Qutb, âIslamic Approach to Social Justice,â 117-130, in Khurshid Ahmad (ed.), Islam: Its Meaning and Message (Leicester, UK: The Islamic Foundation, 2010, ISBN 0860372871).

- â Akbar S. Ahmed, Islam Today (London: I. B. Taurus, 2002, ISBN 1860642578), 62.

- â Menocal, 11.

- â Yohanan Friedmann, Tolerance and coercion in Islam: Interfaith relations in the Muslim tradition (Cambridge University Press, 2003, ISBN 9780521827034), 1.

- â OâShea, 8-9.

- â Science and Scholarship in Al-Andalas Islam and Islamic History in Arabia and The Middle East. Retrieved August 12, 2022.

- â Ahmed, 71.

- â John Edwards, A Conquistador Society? The Spain Columbus Left History Today 42 (May 1992): 11. Retrieved August 12, 2022.

- â Ahmed, 71.

- â Berchman Bittle, A Saint A Day (Bruce Publishing Company, 1958).

- â Christopher Hibbert, House of Medici, Its Rise and Its Fall (William Morrow, 1999, ISBN 978-0688053390), 236.

- â Gerald Massey, A Book of the Beginnings (Martino Fine Books, 2016, ISBN 1614279470).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ahmad, Khurshid (ed.). Islam: Its Meaning and Message. Leicester, UK: The Islamic Foundation, 2010 (original 1991). ISBN 0860372871

- Ahmed, Akbar S. Islam Today. London: I. B. Taurus, 2002. ISBN 1860642578

- Bittle, Berchman. A Saint A Day. Bruce Publishing Company, 1958.

- Carew, Jan. Rape of Paradise. Brooklyn, NY: A & B Books, 1994. ISBN 9781881316794

- Constable, Olivia Remie (ed.) Medieval Iberia: Readings from Christian, Muslim and Jewish Sources. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1997. ISBN 0812233336

- Daniel, Norman. Islam and the West: The Making of an Image. Oxford: OneWorld, 1997. ISBN 1851681299

- Davis, David Brion. The Problem of Slavery in Western Culture. Oxford University Press, 1988. ISBN 978-0195056396

- Fletcher, Richard. The Cross and the Crescent: Christianity and Islam from Muhammad to the Reformation. Viking, 2004. ISBN 9780670032716

- Friedmann, Yohanan. Tolerance and coercion in Islam: Interfaith relations in the Muslim tradition. Cambridge University Press, 2003. ISBN 9780521827034

- Gairdner, William Henry Temple. The Rebuke of Islam. Wentworth Press, 2019 (original 1920). ISBN 978-0526398485

- Hibbert, Christopher. The House of Medici, Its Rise and Fall. William Morrow, 1999. ISBN 978-0688053390

- Lewis, Bernard. The Muslim Discovery of Europe. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1982. ISBN 9780297781400

- Lewis, Bernard. Race and Slavery in The Middle East. NY: Oxford University Press, 1990. ISBN 9780195062830

- Massey, Gerald. A Book of the Beginnings. Martino Fine Books, 2016 (original 1881). ISBN 1614279470

- Menocal, MarĂa Rosa. The Ornament of the World: How Muslims. Jews and Christians Created a Culture of Tolerance in Medieval Spain. Back Bay Books, 2003. ISBN 0316168718

- OâShea, Stephen. Sea of Faith. NY: Walker, 2006. ISBN 0802714986

- Snowden, Frank M. Before Color Prejudice: The Ancient View of Blacks. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1991. ISBN 0674063813

- Southern, R. W. Western View of Islam in the Middle Ages. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1962. ISBN 0674950658

- Van Sertima, Ivan. Golden Age of the Moor. Transaction Publishers, 1993. ASIN B000KWY94Q

External links

All links retrieved June 1, 2025.

- Sigillum Secretum (Secret Seal) Frontline

- Who Were the Moors? National Geographic

- The Moors Community, a story African American Registry (AAREG)

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.