Canaan

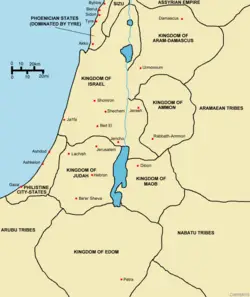

Canaan is an ancient term for a region approximating present-day Israel, the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, plus adjoining coastal lands and parts of Lebanon, Syria, and Jordan.

Canaanites are mentioned extensively in the Bible, as well as in Mesopotamian and Ancient Egyptian texts. According to the Bible, the land of Canaan was the "promised land" which God gave to Abraham and his descendants. The Canaanites themselves, however, were considered to be the implacable enemies of the Israelites, who practiced a decadent and idolatrous religion. Contemporary archaeologists, however, see much continuity between the Canaanite population and the early Israelites, with whom they shared a common language and customs.

The term "Canaan land" is also used as a metaphor for any land of promise or spiritual state of liberation from oppression. Moses' journey from Egypt to the promised land of Canaan thus symbolizes a people's journey from oppression to freedom, from sin to grace.

Historical overview

Human habitation of the land of Canaan goes far back with both Cro-magnon and Neanderthal skeletons having been unearthed from Paleolithic times. A settled agricultural community was present at Jericho from about 8000 B.C.E. By 3000 B.C.E., settlement in towns and villages was widespread.

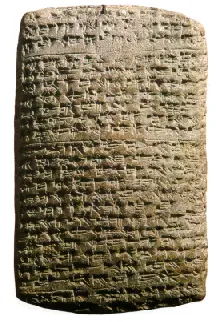

The earliest written mention of the area later called Canaan comes in the eighteenth century B.C.E. in Mesopotamian sources. The term Canaan and Canaanite first appear around the fifteenth century B.C.E. in cuneiform, Phoenician, and Egyptian, inscriptions.

Semitic peoples are thought to have appeared in Canaan in the early Bronze Age, prior to 2000 B.C.E. Writing began to appear shortly thereafter. The Semitic people known as the Amorites became the dominant population group during this period, migrating from the northeast. Also entering from the north were the Hurrians (Horites). Egyptians and the Hyksos, (see below) entered the region from the south.

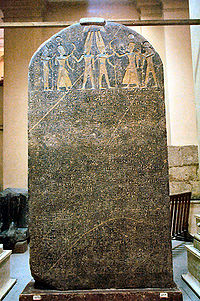

In the Late Bronze age (1550-1200 B.C.E.), Egypt controlled most of Canaan through a system of vassal city-states. Hittite and Apiru (possibly Hebrew) attackers sometimes captured Canaanite towns or harassed them from the countryside. Israelite civilization began to emerge in the historical record in the late thirteenth century B.C.E., with a mention on the Merenptah stele among those nations conquered by the Egyptian monarch.

Historians debate whether Israel's rise represented an invasion, gradual infiltration, a cultural transformation of native Canaanite population, or a combination of the above. With the establishment of the kingdoms of Judah and Israel, the Canaanite, Philistine, and Phoenician peoples co-existed with the Israelites (though not always peacefully), along with other populations such as the Amorites, Edomites, and Moabites to the east and south. From the tenth through the seventh centuries, these nations were strongly pressured and sometimes conquered by Syrian, Assyrian, Egyptian, and finally Babylonian forces. The latter finally came to a position of complete dominance in the sixth century B.C.E.

Etymology and early references

The Canaanite language refers to a group of closely related Semitic languages. Hebrew was once a southern dialect of the Canaanite language, and Ugaritic, a northern one. Canaanite is the first language to use a Semitic alphabet, from which most other scripts derive.

Historically, one of the first mentions of the area later known as Canaan appears in a document from the eighteenth century B.C.E. found in the ruins of Mari, a former Sumerian outpost in Syria. Apparently, Canaan at this time existed as a distinct political entity (probably a loose confederation of city-states). Soon after this, the great law-giver Hammurabi (1728-1686 B.C.E.), first king of a united Babylonia, extended Babylonian influence over Canaan and Syria.

Tablets found in the Mesopotamian city of Nuzi use the term Kinahnu ("Canaan") as a synonym for red or purple dye, apparently a renowned Canaanite export commodity. The purple cloth of Tyre in Phoenicia was well known far and wide.

The Bible attributes the name to a single person, Canaan, the son of Ham and the grandson of Noah, whose offspring correspond to the names of various ethnic groups in the land of Canaan (Gen. 10).

Egyptian Canaan

During the second millennium B.C.E., ancient Egyptian texts refer to Canaan as an Egyptian province, whose boundaries generally corroborate the definition of Canaan found in the Hebrew Bible: bounded to the west by the Mediterranean Sea, to the north in the vicinity of Hamath in Syria, to the east by the Jordan Valley, and to the south by a line extended from the Dead Sea to around Gaza (Numbers 34).

At the end of the Middle Kingdom era of Egypt, a breakdown in centralized power allowed for the assertion of independence by various rulers. Around 1674 B.C.E., the Semitic people known as Hyksos came to control northern Egypt, evidently leaving Canaan an ethnically diverse land. Ahmose, the founder of the eighteenth dynasty, ended a century of Hyksos rule and the Hyksos were pushed northward, some of them probably settling permanently in Canaan. The ancient Jewish historian Flavius Josephus considered the Hyksos to be Hebrews, although scholarship today leans to the idea that they were only one of several proto-Israelite groups.

Among the other migrant tribes who appear to have settled in the region were the Amorites. Some biblical sources describe them as located in the southern mountain country (Gen. 14:7, Josh. 10:5, Deut. 1:19, 27, 44). Other verses speak of Amorite kings residing at Heshbon and Ashtaroth, east of the Jordan (Num. 21:13, Josh. 9:10, 24:8, 12, etc.). Still other passages seem to regard âAmoriteâ as virtually synonymous with "Canaanite" (Gen. 15:16, 48:22, Josh. 24:15, Judg. 1:34, etc.)âexcept that âAmoriteâ is not used for the population on the coast, of described as Philistines.

Amorites apparently became the dominant ethnic group in the region. In Egyptian inscriptions, the terms Amar and Amurru are applied to the more northerly mountain region east of Phoenicia, extending to the Orontes. Later on, Amurru became the Assyrian term for both southern and northern Canaan. At this time the Canaanite area was apparently divided between two confederacies, one centered upon Megiddo in the Jezreel Valley, the second on the more northerly city of Kadesh on the Orontes River.

In the centuries preceding the appearance of the Biblical Hebrews, Canaan again became tributary to Egypt, although domination was not so strong as to prevent frequent local rebellions and inter-city struggles. Under Thutmose III (1479â1426 B.C.E.) and Amenhotep II (1427â1400 B.C.E.), the regular presence of the strong hand of the Egyptian ruler and his armies kept the Canaanites sufficiently loyal. The reign of Amenhotep III, however, was not quite so tranquil for the Asiatic province. It is believed that turbulent chiefs began to seek other opportunities, although as a rule they could not succeed without the help of a neighboring king.

Egyptian power in Canaan suffered a setback when the Hittites (or Hatti) advanced into Syria in the reign of Amenhotep III and became even more threatening than his successor, displacing the Amurru and prompting a resumption of Semitic migration. The Canaanite city-king, Abd-Ashirta, and his son, Aziruâat first afraid of the Hittitesâlater made a treaty with them. Joining with other external powers, they attacked the districts remaining loyal to Egypt.

In the el Amarna letters (c. 1350 B.C.E.) sent by governors and princes of Canaan to their Egyptian overlord Akhenaten (Amenhotep IV) in the fourteenth century B.C.E. we find, beside Amar and Amurru (Amorites), the two forms Kinahhi and Kinahni, corresponding to Kena' and Kena'an respectively, and including Syria in its widest extent, as Eduard Meyer has shown. The letters are written in the official and diplomatic language Babylonian/Akkadian, though ""Canaanitish"" words and idioms are also in evidence.

In one such letter, Rib-Addi of Biblos sends a touching appeal for aid to his distant Egyptian ruler Amenhotep IV, who was apparently too engaged in his religious innovations to respond to such messages. Rib-addi also refers to attacks from the Apiru, thought by scholars to refer to bands of proto-Israelites that had attacked him and other Canaanite kings during this period ("Apiru," also transliterated "Habiru," is etymologically similar to "Hebrew"). The period corresponds to the biblical era just prior to the judges.

Rib-addi says to his lord, the King of Lands, the Great King, the King of Battle... Let my lord listen to the words of his servant, and let him send me a garrison to defend the city of the king, until the archers come out. And if there are no archers, then all the lands will unite with the 'Apiru... Two cities remain with me, and they (the Apiru) are also attempting to take them from the king's hand. Let my lord send a garrison to his two cities until the arrival of the archers, and give me something to feed them. I have nothing. Like a bird that lies in a net, a kilubi/cage, so I am in Gubla.[1]

Seti I (c. 1290 B.C.E.) is said to have conquered the Shasu, Semitic-speaking nomads living just south and east of the Dead Sea, from the fortress of Taru in "Ka-n-'-na." Likewise, Ramses III (c. 1194 B.C.E.) is said to have built a temple to the god Amen in "Ka-n-'-na." This geographic name probably meant all of western Syria and Canaan. Archaeologists have proposed that Egyptian records of the thirteenth century B.C.E. are early written reports of a monotheistic belief in Yahweh noted among the nomadic Shasu.[2][3]

Biblical Canaanites

In the biblical narrative, Canaan was the "promised land" given to Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, and their descendants by God after Abraham responded to God's call and migrated with his family from Haran. Although it was already inhabited by the "Canaanites," God instructed Moses, Joshua, and the Israelites to drive out its inhabitants and take the land as their own possession.

The part of the book of Genesis often called the Table of Nations describes the Canaanites as being descended from an ancestor himself called Canaan. It also lists several peoples about Canaan's descendants, saying:

Canaan is the father of Sidon, his firstborn; and of the Hittites, Jebusites, Amorites, Girgashites, Hivites, Arkites, Sinites, Arvadites, Zemarites, and Hamathites. Later the Canaanite clans scattered and the borders of Canaan reached from Sidon toward Gerar as far as Gaza, and then toward Sodom, Gomorrah, Admah and Zeboiim, as far as Lasha. (Gen. 10:15â19)

A biblical story involving Noah's grandson Canaan seems to represent an origin legend concerning the ancient discovery of the cultivation of grapes around 4000 B.C.E. in the area of Ararat, which is associated with Noah. The story also accounts for the supposed superiority of the Semitic people over the Canaanites, who were to be their servants.

After the Great Flood, Noah planted a vineyard and made wine but became drunk. While intoxicated, an incident occurred involving Noah and his youngest son, Ham. Afterward, Noah cursed Ham's son Canaan to a life of servitude to his brothers (Gen. 9:20â27). While "Canaan" was the ancestor of the Canaanite tribes, "Shem" was the ancestor of the Israelites, Moabites, Edomites, and Ammonites, who dominated the inland areas around the Jordan Valley.

The Bible describes God cautioning the Israelites against the idolatry of the Canaanites and their fertility cult (Lev. 18:27). The land of the Canaanites was thus deemed suitable for conquest by the Israelites partly on moral grounds. They were to be "driven out," their enslavement was allowed, and one passage states that they are not to be left alive in the cities conquered by the Israelites (Deut. 20:10â18):

In the cities of the nations the Lord your God is giving you as an inheritance, do not leave alive anything that breathes. Completely destroy themâthe Hittites, Amorites, Canaanites, Perizzites, Hivites and Jebusitesâas the Lord your God has commanded you. (Deut. 20:16-17)

Leviticus 18, on the other hand allows for non-Israelite populations to remain in the land, so long as they refrain from sexual immorality and human sacrifice.

Critical views

Contemporary archaeologists believe that the Israelites themselves were, for the most part, originally Canaanites (including Amorites, Apiru, Shashu, possibly Hyksos, and others) who federated into the nations of Judah and Israel from the eleventh century B.C.E. onward, rather than being an ethnically homogeneous group that migrated en masse from Egypt, as the Bible reports.

The story of the Kenites (Judges 1) joining Judah is an example of the Bible itself confirming the theory that non-Israelite people federated with Israel in Canaan. Moreover, the Perizzites are usually named as a Canaanite tribe against whom Israel must fight (Gen. 3:8 and 15:19, etc.), but Numbers 26:20 identifies them as part of the lineage and tribe of Judah, through his son Perez.[4]. The latter reference may reflect the fact that Perizzites joined Judah in Canaan and were literally "adopted" into Judah's origin-story. Meanwhile, the biblical story of the conquest of Canaan may represent the memories of Apiru victories written down several centuries after the fact and filtered through the religious viewpoint of that later time.[3]

According to this and similar theories "Israelite" migration from the south indeed took place, but occurred in phases as various groups moved north into Canaan. Moreover, some of the groups that later identified with the Israelites had lived in Canaan for centuries. Thus the distinction between Canaanites and Israelites was once very faint, if it existed at all. Possibly the earliest distinction was political: the Canaanites were ruled by the Egyptian-dominated city-states while the proto-Israelites were Canaanite groups who lived in the countryside outside of that political orbitâhence, Apiru. Eventually the Israelites came to see themselves as a people separate from the Canaanites, largely for religious reasons.

The Israelite religion itself went through an evolutionary process, beginning with the fusion of the Canaanite god El with the desert god Yahweh, and evolving into the assertion that Yahweh/El alone could be worshiped by the Israelites. The rejection of traditional Canaanite religion resulted in the development of a religious mythology in which the Israelites were never a part of Canaanite culture, and the Canaanite gods were enemies of Yahweh/El, rather than members of the assembly of the gods with El as their chief.

Canaanite Religion

The religion of the Canaanites was inherited primarily from the great earlier civilizations of Mesopotamia. Lacking the rich supply of water for irrigation from such mighty rivers as the Tigris and Euphrates, however, Canaanite religion was especially concerned with rain as a key element in the fertility and life of the land.

The chief deity was El, who reigned over the assembly of the gods. Although technically the supreme god, El was not the most important deity in terms of worship and devotion. One of his sons, Baal/Hadad was an especially important deity, the god of rain, storms, and fertility. The Israelite god Yahweh could also be considered originally a Sashu/Canaanite deity, who in early psalms shares many characteristics with El and Baal. El's consort Ashera was a mother goddess, also associated with fertility. Another female deity, sometimes synonymous with Ashera, was Astarte or Ashtoreth, who can be viewed as the Canaanite version of the Mesopotamian goddess Ishtar. Baal's sister Anat, meanwhile, was the virginal goddess of war similar to the later Greek Diana.

El and Baal were sometimes associated with bull-worship, and cattle and other offerings were often sacrificed to them, as well as to Yahweh. Ancient stone pillars and horned altars have been also found in numerous sites throughout Canaan, as well as the remains of temples, statues, and other artifacts dedicated to these deities. Bread offerings were made to Ashera or Astarte as the "Queen of Heaven," and statuettes of the goddess of fertility have been found not only in Canaanite temples but also in many domestic buildings. A number of other names are assigned to gods with similar characteristics to those of El, Baal, or Yahweh, for example Dagon, Chemosh, and Moloch.

The biblical patriarchs and later Israelites are described in the Bible as sharing with their Canaanite neighbors the recognition of El as the supreme deity. Yahweh is affirmed in the Bible to be identical with El. However, the early prophetic and priestly tradition declared that no other deities than Yahweh/El should be worshiped by the Israelites. In this view, other gods existed, but they were specific to other peoples, and the Israelites should have nothing to do with them. Later prophets went so far as to declare that Yahweh alone was God. Archaeologists, however, indicate that goddess worship and Baal-worship persisted among the common folk as well as the kings of Israel and Judah until at least the time of the exile.[5]

Biblical tradition makes much of such practices as sexual fertility rites and human sacrifice among the Canaanite tribes. It is generally agreed that the worship of Baal and Ashera sometimes involved such rites, although it is difficult to know how frequent or widespread this may have been. Human sacrifice was also practiced by both the Canaanites and the Israelites. The Hebrew prophets, however, sharply condemned such practices.

The Promised Land

As the land promised by God to the Israelites, "Canaan" has come to mean any place of hope. For the Jews, it was the land of promise where they would eventually return after being scattered every since the destruction of the Temple. That hope was fulfilled for many Jews with the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948.

For Christians, "Canaan" often takes a more spiritual meaning, having to do with the afterlife, or sometimes with the realm to be established at Christ's Second Coming. In the words of the American spiritual song "Where the Soul of Man Never Dies":

- To Canaan's land I'm on my way

- Where the soul of man never dies

- My darkest night will turn to day

- Where the soul (of man) never dies.

Notes

- â AndrĂ© Dollinger (ed.), The Amarna Letters: Letters by Rib-Addi of Byblos. Retrieved July 24, 2007.

- â William G. Dever, Who Were the Early Israelites and Where Did They Come From? (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2006, ISBN 0802844162), 128, 236.

- â 3.0 3.1 Neil Asher Silberman and Israel Finkelstein, The Bible Unearthed (New York: Free Press, 2001, ISBN 0684869136).

- â This view, however, is based on the assumption of recent commentators that the names "Perizi" and "Perazi" are identical.

- â William G. Dever, Did God Have A Wife? Archaeology and Folk Religion In Ancient Israel (Grand Rapids, MI: William. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2005, ISBN 0802828523).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Abright, William F. The Archaeology of Palestine, 2nd ed. Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith Publisher Inc., 1985. ISBN 0844600032

- Bright, John. A History of Israel, 4th ed. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2000. ISBN 0664220681

- Coogan, Michael (ed.). Stories from Ancient Canaan. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 1978. ISBN 978-0664241841

- Dever, William G. Who Were the Early Israelites and Where Did They Come From? Grand Rapids, MI: William. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2006. ISBN 0802844162

- Dever, William G. Did God Have A Wife? Archaeology and Folk Religion In Ancient Israel. Grand Rapids, MI: William. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2005. ISBN 0802828523

- Miller, J. Maxwell. A History of Ancient Israel and Judah. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 1986. ISBN 066421262X

- Redford, Donald. Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times. Reprint edition, 1993. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1992. ISBN 978-0691000862

- Silberman, Neil Asher and Israel Finkelstein. The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts. NMew York: Free Press, 2002. ISBN 0684869136

- Tubb, Jonathan N. Canaanites. University of Oklahoma Press, 1999. ISBN 080613108X

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.