Salvador Dalí

| Salvador Dalí | |

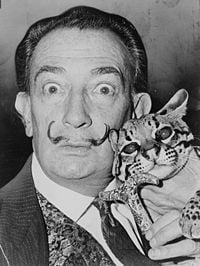

Dalí, photo by Carl Van Vechten, November 29, 1939 | |

| Born | May 11, 1904 Figueres, Catalonia, Spain |

| Died | January 23, 1989 Figueres, Catalonia, Spain |

| Field | Painting, Drawing, Photography, Sculpture |

| Training | San Fernando School of Fine Arts, Madrid |

| Movement | Cubism, Dada, Surrealism |

| Famous works | The Persistence of Memory (1931) Face of Mae West Which May Be Used as an Apartment, (1935) Soft Construction with Boiled Beans (Premonition of Civil War) (1936) Ballerina in a Death's Head (1939) The Temptation of Saint Anthony (1946) Galatea of the Spheres (1952) Young Virgin Auto-Sodomized by the Horns of Her Own Chastity (1954) |

Salvador Felipe Jacinto Dalí Domènech, Marquis of Pubol or Salvador Felip Jacint Dalí Domènech (May 11, 1904 – January 23, 1989), known popularly as Salvador Dalí, was a Catalan Spanish artist and one of the most important painters of the twentieth century. A skilled draftsman, best known for the striking, bizarre, and dreamlike images in his surrealist work. Dalí joined the surrealists in 1929, and participated in the rapid establishment of the visual style between 1930 and 1935. (Surrealism as a visual movement sought to expose psychological truth by stripping ordinary objects of their normal significance, in order to create a compelling image that was beyond ordinary formal organization, in order to evoke empathy from the viewer.) Like cubism and other modern art movements, surrealism attempted to change the perspective of the viewer in order that the common and ordinary object could be seen in a new light. His painterly skills are often attributed to the influence of Renaissance masters.[1] His best known work, The Persistence of Memory, was completed in 1931. Salvador Dalí's artistic repertoire also includes film, sculpture, photography. He collaborated with Walt Disney on the Academy Award-nominated short cartoon, "Destino," which was released posthumously in 2003.

Greatly imaginative, Dalí had an affinity for doing unusual things to draw attention to himself. This sometimes irked those who loved his art as much as it annoyed his critics, since his eccentric manner sometimes drew more public attention than his artwork.[2]

Early life

Dalí was born on May 11, 1904, at 8:45 A.M. local time[3] in the town of Figueres, in the Empordà region close to the French border in Catalonia, Spain. Concerning his birth, Dalí "was born at his domicile at forty five minutes after eight o'clock on the eleventh day of the present month of May."[4] Dalí's older brother, also named Salvador, had died of meningitis three years earlier at the age of 7.[5] His father, Salvador Dalí i Cusí, was a middle-class lawyer and notary[6] whose strict disciplinarian approach was tempered by his wife, Felipa Domenech Ferres, who encouraged her son's artistic endeavors.[7] When he was five, Dalí was taken to his brother's grave and told by his parents that he was his brother's reincarnation,[8] which he came to believe.[9] Of his brother, Dalí said: "my brother died at the age of seven from an attack of meningitis, three years before I was born… [we] resembled each other like two drops of water, but we had different reflections."[10] He "was probably a first version of myself but conceived too much in the absolute."[11]

Dalí also had a sister, Ana María, who was three years his junior.[6] In 1949 his sister, Ana Maria, published a book about her brother, Dalí As Seen By His Sister.[12]

Dalí attended drawing school, where he first received formal art training. In 1916, Dalí discovered modern painting on a summer vacation to Cadaqués (in the nearby Costa Brava) with the family of Ramon Pichot, a local artist who made regular trips to Paris.[6] The next year, Dalí's father organized an exhibition of his charcoal drawings in their family home. He had his first public exhibition at the Municipal Theater in Figueres in 1919. In 1921, Dalí’s mother died of breast cancer when he was 16 years old. His mother's death "was the greatest blow I had experienced in my life. I worshipped her… I could not resign myself to the loss of a being on whom I counted to make invisible the unavoidable blemishes of my soul."[13] After her death, Dalí’s father married the sister of his deceased wife; Dalí somewhat resented this marriage.[6]

Madrid and Paris

In 1922, Dalí moved into the Residencia de estudiantes (Students' Residence) in Madrid[6] and there studied at the San Fernando School of Fine Arts. Dalí already drew attention as an eccentric, wearing long hair and sideburns, coat, stockings and knee breeches in the fashion style of a century earlier. But his paintings, where he experimented with Cubism, earned him the most attention from his fellow students. In these earliest Cubist works, he probably did not completely understand the movement, since his only information on Cubist art came from a few magazine articles and a catalogue given to him by Pichot, and there were no Cubist artists in Madrid at the time.

Dalí also experimented with Dada, which influenced his work throughout his life. At the San Fernando School of Fine Arts, he became close friends with the poet Federico García Lorca, with whom he might have become romantically involved,[14] and filmmaker Luis Buñuel. Dalí was expelled from the academy in 1926 shortly before his final exams when he stated that no one on the faculty was competent enough to examine him.[15]

That same year he made his first visit to Paris where he met with Pablo Picasso, whom young Dalí revered; Picasso had already heard favorable things about Dalí from Joan Miró. Dalí did a number of works heavily influenced by Picasso and Miró over the next few years as he moved toward developing his own style.

Some trends in Dalí's work that would continue throughout his life were already evident in the 1920s, however. Dalí devoured influences of all styles of art he could find and then produced works ranging from the most academically classic to the most cutting-edge avant-garde,[16] sometimes in separate works and sometimes combined. Exhibitions of his works in Barcelona attracted much attention and mixtures of praise and puzzled debate from critics.

Dalí grew a flamboyant moustache, which became iconic of him; it was influenced by that of seventeenth century Spanish master painter Diego Velázquez.

1929 until World War II

Dalí collaborated with the surrealistic film director Luis Buñuel in 1929 on the short film Un chien andalou (English: An Andalusian Dog) and met his muse, inspiration, and future wife Gala,[17] born Helena Dmitrievna Deluvina Diakonova, a Russian immigrant eleven years his senior who was then married to the surrealist poet Paul Éluard. He was mainly responsible for helping Buñuel write the script for the film, but Dalí later claimed to have had a greater creative force in the filming of the project. Contemporary accounts, however, do not substantiate this claim.[18] In the same year, Dalí had important professional exhibitions and officially joined the surrealist group in the Montparnasse quarter of Paris (although his work had already been heavily influenced by surrealism for two years). The surrealists hailed what Dalí called the "Paranoiac-critical method" of accessing the subconscious for greater artistic creativity.[6][7]

In 1931, Dalí painted one of his most famous works, The Persistence of Memory.[19] Sometimes called Soft Watches or Melting Clocks, the work introduced the surrealistic image of the soft, melting pocket watch. The general interpretation of the work is that the soft watches debunk the assumption that time is rigid or deterministic, and this sense is supported by other images in the work, including the ants and fly devouring the other watches.[20]

Dalí and Gala, having lived together since 1929, were married in 1934 in a civil ceremony. They remarried in a Roman Catholic ceremony in 1958.

In 1936, Dalí took part in the London International Surrealist Exhibition. His lecture entitled Fantomes paranoiaques authentiques was delivered wearing a deep-sea diving suit.[21] When Francisco Franco came to power in the aftermath of the Spanish Civil War, Dalí was one of the few Spanish intellectuals supportive of the new regime, which put him at odds with his predominantly Marxist surrealist fellows over politics, eventually resulting in his official expulsion from this group.[17] At this, Dali retorted, "Le surréalisme, c'est moi."[15] André Breton coined the anagram "avida dollars" (for Salvador Dalí), which more or less translates to "eager for dollars,"[22] by which he referred to Dalí after the period of his expulsion; the surrealists henceforth spoke of Dalí in the past tense, as if he were dead. The surrealist movement and various members thereof (such as Ted Joans) would continue to issue extremely harsh polemics against Dalí until the time of his death and beyond. As World War II started in Europe, Dalí and Gala moved to the United States in 1940, where they lived for eight years. In 1942, he published his autobiography, The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí.

Later years in Catalonia

Dalí spent his remaining years back in his beloved Catalonia starting in 1949. His choice to continue living in Spain while it was ruled by Franco drew criticism from progressives and many other artists.[23] As such, probably at least some of the common dismissal of Dalí's later works had more to do with politics than the actual merits of the works themselves. In 1959, André Breton organized an exhibit called, Homage to Surrealism, celebrating the Fortieth Anniversary of Surrealism, which contained works by Dalí, Joan Miró, Enrique Tábara, and Eugenio Granell. Breton vehemently fought against the inclusion of Dalí's Sistine Madonna in the International Surrealism Exhibition in New York the following year.[24]

Late in his career, Dalí did not confine himself to painting but experimented with many unusual or novel media and processes: he made bulletist works[25] and was among the first artists to employ holography in an artistic manner.[26] Several of his works incorporate optical illusions. In his later years, young artists like Andy Warhol proclaimed Dalí an important influence on pop art.[27] Dalí also had a keen interest in natural science and mathematics. This is manifested in several of his paintings, notably in the 1950s when he painted his subjects as composed of rhinoceros horns, signifying divine geometry (as the rhinoceros horn grows according to a logarithmic spiral) and chastity (as Dalí linked the rhinoceros to the Virgin Mary).[28] Dalí was also fascinated by DNA and the hypercube; the latter, a 4-dimensional cube, is featured in the painting Crucifixion (Corpus Hypercubus).

In 1960, Dalí began work on the Dalí Theatre and Museum in his home town of Figueres; it was his largest single project and the main focus of his energy through 1974. He continued to make additions through the mid-1980s. He found time, however, to design the Chupa Chups logo in 1969. In 1969, he was responsible for creating the advertising aspect of the 1969 Eurovision Song Contest, and created a large metal sculpture, which stood on the stage at the Teatro Real in Madrid.

In 1982, King Juan Carlos of Spain bestowed on Dalí the title Marquis of Pubol, for which Dalí later paid him back by giving him a drawing (Head of Europa, which would turn out to be Dalí's final drawing) after the king visited him on his deathbed.

Gala died on June 10, 1982. After Gala's death, Dalí lost much of his will to live. He deliberately dehydrated himself—possibly in a suicide attempt, possibly in an attempt to put himself into a state of suspended animation, as he had read that some microorganisms could do. He moved from Figueres to the castle in Pubol which he had bought for Gala and was the site of her death. In 1984, a fire broke out in his bedroom[29] under unclear circumstances—possibly a suicide attempt by Dalí, possibly simple negligence by his staff.[15] In any case, Dalí was rescued and returned to Figueres where a group of his friends, patrons, and fellow artists saw to it that he was comfortable living in his Theater-Museum for his final years.

There have been allegations that his guardians forced Dalí to sign blank canvases that would later (even after his death) be used and sold as originals.[30] As a result, art dealers tend to be wary of late works attributed to Dalí. He died of heart failure at Figueres on January 23, 1989 at the age of 84, and he is buried in the crypt of his Teatro Museo in Figueres.

Symbolism

Dalí employed extensive symbolism in his work. For instance, the hallmark soft watches that first appear in The Persistence of Memory suggest Einstein's theory of relativity, in which time is relative, not fixed.[20] The idea to use clocks in this symbolic fashion came to Dalí when he was staring at a runny piece of Camembert cheese during a hot day in August.[31]

The elephant is also a recurring image in Dalí's works, appearing first in his 1944 work Dream Caused by the Flight of a Bee around a Pomegranate a Second Before Awakening. The elephants, inspired by Gian Lorenzo Bernini's sculpture in Rome of an elephant carrying an obelisk,[32] are portrayed "with long, multi-jointed, almost invisible legs of desire"[33] along with obelisks on their backs. Coupled with the image of their brittle legs, these encumbrances, noted for their phallic overtones, create a sense of phantom reality. "The elephant is a distortion in space," one analysis explains, "its spindly legs contrasting the idea of weightlessness with structure."[33]...I am painting pictures which make me die for joy, I am creating with an absolute naturalness, without the slightest aesthetic concern, I am making things that inspire me with a profound emotion and I am trying to paint them honestly.

— Salvador Dalí, in Dawn Ades, Dalí and Surrealism,

The egg is another common Dalíesque image. He connects the egg to the prenatal and intrauterine, thus using it to symbolize hope and love;[34] it appears in The Metamorphosis of Narcissus. Various animals appear throughout his work as well: ants point to death, decay, and immense sexual desire; the snail is connected to the human head (he saw a snail on a bicycle outside Freud’s house when he first met Sigmund Freud); and locusts are a symbol of waste and fear.[34]

His fascination with ants has a strange explanation. When Dalí was a young boy he had a pet bat. One day he discovered his bat dead, covered in ants. He thus developed a fascination with and fear of ants.

Endeavors outside painting

Dalí was a versatile artist, not limiting himself only to painting in his artistic endeavors. Some of his more popular artistic works are sculptures and other objects, and he is also noted for his contributions to theater, fashion, and photography, among other areas.

Two of the most popular objects of the surrealist movement were the Lobster Telephone and the Mae West Lips Sofa, completed by Dalí in 1936 and 1937, respectively. The Scottish patron Edward James commissioned both of these pieces from Dalí; James, an eccentric who had inherited a large English estate when he was five, was one of the foremost supporters of the surrealists in the 1930s.[35] "Lobsters and telephones had strong sexual connotations for [Dalí]" according to the display caption for the Lobster Telephone at the Tate Gallery, "and he drew a close analogy between food and sex."[36] The telephone was functional, and James purchased four of them from Dalí to replace the phones in his retreat home. One now appears at the Tate Gallery; the second can be found at the German Telephone Museum in Frankfurt; the third belongs to the Edward James Foundation; and the fourth is at the National Gallery of Australia.[35] The wood and satin Mae West Lips Sofa was shaped after the lips of actress Mae West, who Dalí apparently found fascinating.[17] West was previously the subject of Dalí's 1935 painting The Face of Mae West. The Mae West Lips Sofa currently resides at the Brighton and Hove Museum in England.

In theater, Dalí is remembered for constructing the scenery for García Lorca's 1927 romantic play Mariana Pineda.[37] For Bacchanale (1939), a ballet based on and set to the music of Richard Wagner's 1845 opera Tannhäuser, Dalí provided both the set design and the libretto.[38] Bacchanale was followed by set designs for Labyrinth in 1941 and The Three-Cornered Hat in 1949.[39]

Dalí also delved into the realms of filmmaking, most notably playing large roles in the production of Un Chien Andalou, a 17-minute French art film co-written with Luis Buñuel which is widely remembered for the graphic scene of the slicing open of a human eyeball with a razor. Dalí's other major film work is the Walt Disney cartoon production Destino; clocking in at a mere six minutes, it contains dream-like images of strange figures flying and walking about. Dalí also designed the set for the dream sequence in Alfred Hitchcock's Spellbound (1945 film) which relies heavily on the then newly emerging practice of psychoanalysis, although ironically, aside from the dream sequence, the plot is based much more on Freud's earlier trauma theory than his psychoanalytic theories.

Dalí built a repertoire in the fashion and photography industries as well. In fashion, Dalí was hired by Elsa Schiaparelli to produce a white dress with a lobster print. Other designs Dalí made for her include a shoe-shaped hat and a pink belt with lips for a buckle. He was also involved in creating textile designs and perfume bottles. With Christian Dior in 1950, Dalí created a special "costume for the year 2045."[38] Photographers with whom he collaborated include Man Ray, Brassaï, Cecil Beaton, and Philippe Halsman. With Man Ray and Brassaï, Dalí photographed nature, while with the others he explored a range of obscure topics, including with Halsman the Dalí Atomica series (1948)—inspired by his painting Leda Atomica—which in one photograph depicts "a painter’s easel, three cats, a bucket of water and Dalí himself floating in the air."[38]

Dalí was fascinated with the paradigm shift that accompanied the birth of quantum mechanics in the twentieth century. In 1958 inspired by Werner Heisenberg's Uncertainty principle, he wrote in his "Anti-Matter Manifesto": "In the Surrealist period I wanted to create the iconography of the interior world and the world of the marvelous, of my father Freud. Today the exterior world and that of physics, has transcended the one of psychology. My father today is Dr. Heisenberg."[40] In this respect, The Disintegration of the Persistence of Memory, which appeared in 1954, hearkened back to The Persistence of Memory, portraying that painting in fragmentation and disintegration, and summarizing Dalí's acknowledgment of the new science.[40]

Architectural achievements include his Port Lligat house near Cadaqués as well as the Dream of Venus surrealist pavilion at the 1939 World's Fair which contained within it a number of unusual sculptures and statues. His literary works include The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí (1942), Diary of a Genius (1952–1963), and Oui: The Paranoid-Critical Revolution (1927–1933). Dalí worked extensively in the graphic arts producing many etchings and lithographs. While his early work in printmaking is equal in quality to his important paintings, as he grew older he viewed printmaking in financial terms, selling the rights to images without involving himself in the print production itself. In addition a large number of unauthorized fakes were produced in the eighties and ninties, further confusing the Dalí print market.

Politics and personality

The politics of Salvador Dalí played a significant role in his emergence as an artist. He has sometimes been portrayed as a fascist supporter.[23] André Breton, in particular, nicknamed him "Avida Dollars" (an anagram) and made a strong effort to dissociate his name from surrealists proper. The reality is probably somewhat more complex; in any event, he was probably not an anti-semite, given that he was a friendly acquaintance of famed architect and designer Paul László, who was ethnically Jewish.

In his youth, Dalí embraced for a time both anarchism and communism. His writings afford various anecdotes of radical political statements made more to shock his listeners than from any deep conviction, which was in keeping with Dalí's allegiance to the Dada movement. When he fell into the circle of mostly Marxist surrealists who denounced as enemies the monarchists on one hand and the anarchists on the other, Dalí explained to them that he personally was an anarcho-monarchist.

With the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, Dalí fled from fighting and refused to align himself with any group. After his return to Catalonia following World War II, Dalí became closer to the Franco regime. Some of Dalí's statements supported the repression enacted under Franco's fascist regime, congratulating Franco for his actions aimed "at clearing Spain of destructive forces." Dalí sent telegrams to Franco, "praising him for signing death warrants for political prisoners."[23] Dalí even painted a portrait of Franco's grand-daughter. It is impossible to determine whether his tributes to Franco were sincere or whimsical; he also once sent a telegram praising the Conducător, Romanian Communist leader Nicolae Ceauşescu, for his adoption of a sceptre as part of his regalia. The Romanian daily newspaper Scînteia published it, without suspecting its mocking aspect. Dalí's eccentricities were tolerated by the Franco regime, since not many world-famous artists would accept living in Spain. One of Dalí's few possible bits of open disobedience was his continued praise of Federico García Lorca even in the years when Lorca's works were banned.[14]

In Carlos Lozano's biography, Sex, Surrealism, Dalí and Me, produced in collaboration with Clifford Thurlow, Lozano makes it clear that Dalí never stopped being a surrealist. As Dalí said of himself: "the only difference between me and the surrealists is that I am a surrealist."[22] Everything, including his support for Franco and telegrams to Ceauşescu must be seen in this light. Dalí is famous for having said "every morning upon awakening, I experience a supreme pleasure: that of being Salvador Dalí."[41]

Listing of selected works

Dalí produced over 1,500 paintings in his career,[42] in addition to producing illustrations for books, lithographs, designs for theater sets and costumes, a great number of drawings, dozens of sculptures, and various other projects, including an animated cartoon for Disney. Below is a chronological sample of important and representative work, as well as some notes on what Dalí did in particular years:[1]

- 1910 Landscape Near Figueras

- 1913 Vilabertin

- 1916 Fiesta in Figueras (begun 1914)

- 1917 View of Cadaqués with Shadow of Mount Pani

- 1918 Crepuscular Old Man (begun 1917)

- 1919 Port of Cadaqués (Night) (begun 1918) and Self-portrait in the Studio

- 1920 The Artist’s Father at Llane Beach and View of Portdogué (Port Aluger)

- 1921 The Garden of Llaner (Cadaqués) (begun 1920) and Self-portrait

- 1922 Cabaret Scene and Night Walking Dreams

- 1923 Self Portrait with L'Humanite and Cubist Self Portrait with La Publicitat

- 1924 Still Life (Syphon and Bottle of Rum) (for García Lorca) and Portrait of Luis Buñuel

- 1925 Large Harlequin and Small Bottle of Rum, and a series of fine portraits of his sister Anna Maria, most notably Figure At A Window

- 1926 Basket of Bread and Girl from Figueres

- 1927 Composition With Three Figures (Neo-Cubist Academy) and Honey is Sweeter Than Blood (his first important surrealist work)

- 1929 Un chien andalou (An Andalusian Dog) film in collaboration with Luis Buñuel, The Lugubrious Game, The Great Masturbator and The First Days of Spring

- 1930 L'Âge d'Or (The Golden Age) film in collaboration with Luis Buñuel

- 1931 The Persistence of Memory (his most famous work, featuring the melting clocks), The Old Age of William Tell, and William Tell and Gradiva

- 1932 The Spectre of Sex Appeal, The Birth of Liquid Desires, Anthropomorphic Bread, and Fried Eggs on the Plate without the Plate. The Invisible Man (begun 1929) completed (although not to Dalí's own satisfaction).

- 1933 Retrospective Bust of a Woman (mixed media sculpture collage) and Portrait of Gala With Two Lamb Chops Balanced on Her Shoulder, Gala in the window

- 1934 The Ghost of Vermeer of Delft Which Can Be Used As a Table and A Sense of Speed

- 1935 Archaeological Reminiscence of Millet’s Angelus and The Face of Mae West

- 1936 Autumn Cannibalism, Lobster Telephone, Soft Construction with Boiled Beans (Premonition of Civil War) and two works titled Morphological Echo (the first of which began in 1934).

- 1937 Metamorphosis of Narcissus, Swans Reflecting Elephants, The Burning Giraffe, Sleep, The Enigma of Hitler, and Mae West Lips Sofa

- 1938 The Sublime Moment and Apparition of a Face and Fruit Dish on the Beach

- 1940 The Face of War

- 1943 The Poetry of America and Geopoliticus Child Watching the Birth of the New Man

- 1944 Galarina and Dream Caused by the Flight of a Bumblebee around a Pomegranate a Second Before Awakening

- 1944-1948 Hidden Faces, a novel

- 1945, Basket of Bread–Rather Death Than Shame and Fountain of Milk Flowing Uselessly on Three Shoes; This year Dalí collaborated with Alfred Hitchcock on a dream sequence to the film Spellbound, to mutual dissatisfaction.

- 1946 The Temptation of St. Anthony

- 1949 Leda Atomica and The Madonna of Port Lligat. Dalí returned to Catalonia this year.

- 1951 Christ of St. John of the Cross and Exploding Raphaelesque Head.

- 1954 Corpus Hypercubus Crucifixion, Young Virgin Auto-Sodomized by the Horns of Her Own Chastity and The Disintegration of the Persistence of Memory (begun in 1952).

- 1955 The Sacrament of the Last Supper, Lonesome Echo, record album cover for Jackie Gleason

- 1956 Still Life Moving Fast, Rinoceronte vestido con puntillas

- 1958 The Rose

- 1959 The Discovery of America by Christopher Columbus.

- 1960 Dalí began work on the Teatro-Museo Gala Salvador Dalí (Dalí Theatre and Museum)

- 1965 Dalí donates a gouache, ink and pencil drawing of the Crucifixion to the Rikers Island jail in New York City. The drawing hung in the inmate dining room from 1965 to 1981.[43]

- 1967 Tuna Fishing

- 1969 Chupa Chups logo

- 1970 The Hallucinogenic Toreador

- 1972 La Toile Daligram

- 1976 Gala Contemplating the Sea

- 1977 Dalí's Hand Drawing Back the Golden Fleece in the Form of a Cloud to Show Gala Completely Nude, Very Far Away Behind the Sun (stereoscopical pair of paintings)

- 1983 Dalí completed his final painting, The Swallow's Tail.

- 2003 Destino, an animated cartoon which was originally a collaboration between Dalí and Walt Disney, is released. Production on Destino began in 1945.

The largest collections of Dalí's work are at the Dalí Theatre and Museum in Figueres, Catalonia, Spain, followed by the Salvador Dalí Museum in Saint Petersburg, Florida, and the Salvador Dalí Gallery in Pacific Palisades, California. Espace Salvador Dalí on Montmartre in Paris, France contains a large collection of his drawings and smaller sculptures.

The unlikeliest venue for Dalí's work was the Rikers Island jail in New York City; a sketch of the Crucifixion he donated to the jail hung in the inmate dining room for 16 years before it was moved to the prison lobby for safekeeping. The drawing was stolen in March 2003 by four prison guards and has not been recovered.[43]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Salvador Dalí. (2000) Dalí: 16 Art Stickers. (Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 0486410749).

- ↑ Stephen Francis Saladyga. "The Mindset of Salvador Dalí". lamplighter (Niagara University) 1 (3) (Summer 2006).

- ↑ Salvador Dalí astrological chart on astrotheme.fr. Accessed 30 September 2006.

- ↑ Salvador Dalí. The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí. (London: Vision Press, 1948), 33

- ↑ Betty Davies. (1998) Shadows in the Sun. (UK: Psychology Press (UK). ISBN 0876309112).

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 Lluís Llongueras. (2004) Dalí. (Mexico: Ediciones B - Mexico. ISBN 8466613439).

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Carlos Rojas. Salvador Dalí, Or the Art of Spitting on Your Mother's Portrait. Penn State Press, 1993. ISBN 027108423).

- ↑ Salvador Dalí. SINA.com. Retrieved on July 31, 2006.

- ↑ Salvador Dalí biography on astrodatabank.com. Accessed 30 September 2006.

- ↑ Dalí, Secret Life, 2

- ↑ Dalí, Secret Life, 2

- ↑ Dalí Biography 1904-1989 - Part Two artelino.com.

- ↑ Dalí, Secret Life, 152-153

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Alain Bosquet, Conversations with Dalí, 1969. 19. (Portable Document File)

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Salvador Dalí: Olga's Gallery. abcgallery. Retrieved on July 22, 2006.

- ↑ Nicola Hodge and Libby Anson. The A-Z of Art: The World's Greatest and Most Popular Artists and Their Works. (California: Thunder Bay Press, 1996.) Online citation.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Landry Shelley. "Dalí Wows Crowd in Philadelphia". Unbound (The College of New Jersey) Spring 2005. Retrieved on July 22, 2006.

- ↑ Michael Koller. Un Chien Andalou. senses of cinema.com. January 2001.

- ↑ Clocking in with Salvador Dalí: Salvador Dalí’s Melting Watches (PDF) from the Salvador Dalí Museum. Retrieved on August 19 2006.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Salvador Dalí, La Conquête de l’irrationnel. (Paris: Éditions surréalistes, 1935), 25.

- ↑ Rob Jackaman. (1989) Course of English Surrealist Poetry Since the 1930s. (Edwin Mellen Press. ISBN 0889469326).

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Artcyclopedia: Salvador Dalí. Retrieved September 4, 2006.

- ↑ Ignacio Javier López. The Old Age of William Tell (A study of Buñuel's Tristana). MLN 116 (2001): 295–314.

- ↑ The Phantasmagoric Universe – Espace Dalí À Montmartre. Bonjour Paris. Retrieved on August 22, 2006.

- ↑ The History and Development of Holography. Holophile. Retrieved on August 22, 2006.

- ↑ Hello, Dalí. Carnegie Magazine. Retrieved on August 22, 2006.

- ↑ Elliott King in Dawn Ades (ed.), Dalí. (Milan: Bompiani Arte, 2004), 456.

- ↑ "Dalí Resting at Castle After Injury in Fire". The New York Times. September 1, 1984. Retrieved July 22, 2006

- ↑ Mark Rogerson. The Dalí Scandal: An Investigation. (Victor Gollancz, 1989. ISBN 0575037865)

- ↑ Salvador Dalí, The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí (New York: Dial Press, 1942), p. 317.

- ↑ Michael Taylor in Dawn Ades (ed.), Dalí (Milan: Bompiani, 2004), p. 342

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Dalí Universe Collection. County Hall Gallery. Retrieved on July 28, 2006.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 "Salvador Dalí's symbolism". County Hall Gallery. Retrieved on July 28, 2006

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Lobster telephone. National Gallery of Australia. Retrieved on August 4, 2006.

- ↑ Tate Collection | Lobster Telephone by Salvador Dalí. Tate Online. Retrieved on August 4, 2006.

- ↑ Federico García Lorca. Pegásos. Retrieved on August 8, 2006.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 Dalí Rotterdam Museum Boijmans. Paris Contemporary Designs. Retrieved on August 8, 2006.

- ↑ Past Exhibitions. Haggerty Museum of Art. Retrieved August 8, 2006.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Dalí: Explorations into the domain of science. The Triangle Online. Retrieved August 8, 2006.

- ↑ The Surreal World of Salvador Dalí. Smithsonian Magazine 2005. Retrieved August 31, 2006.

- ↑ "The Salvador Dalí Online Exhibit" MicroVision [1] accessdate 2006-06-13

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Dalí picture sprung from jail BBC News March 2, 2003

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bosquet, Alain. Conversations with Dali. New York: E. P DUTTON. and CO INC, 1969. ASIN: B000YBZJX8

- Dalí, Salvador. Dalí: 16 Art Stickers. Courier Dover Publications, 2000. ISBN 0486410749

- Dalí, Salvador. The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí. London: Vision Press, 1948.

- Dalí, Salvador and Haakon M. Chevalier (Translator). The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí,

reprint Kessinger Publishing, LLC 2007. ISBN 1432596640 (in English)

- Davies, Betty. Shadows in the Sun. UK: Psychology Press (UK), 1998. ISBN 0876309112

- Hodge, Nicola and Libby Anson. The A-Z of Art: The World's Greatest and Most Popular Artists and Their Works. California: Thunder Bay Press, [1996] reprint Carlton Publishing Group, New Ed. 2002. ISBN 1858685567

- Llongueras, LLuis. Dalí. Mexico: Ediciones B - Mexico. 2004. ISBN 8466613439

- Rogerson, Mark. The Dalí Scandal: An Investigation. Victor Gollancz, 1989. ISBN 0575037865

- Rojas, Carlos. Salvador Dalí, Or the Art of Spitting on Your Mother's Portrait. Penn State Press, 1993. ISBN 027108423

External links

All links retrieved December 22, 2022.

- Dalí's surreal wind-powered organ lacks only a rhinoceros

- UbuWeb: Salvador Dalí – Interview.

- Gala-Salvador Dalí Foundation English language site

- A brush with Dalí's Muse, Guardian article, May 2005

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.