Crucifixion

Crucifixion was an ancient method of execution practiced in the Roman Empire and neighboring Mediterranean cultures, such as the Persian Empire, where a person was nailed to a large wooden cross or stake and left to hang until dead. Contrary to popular belief, those crucified did not die through loss of blood but through asphyxiation as they could no longer hold themselves up to breathe.

The purpose of crucifixion was to provide a gruesome public way to execute criminals and dissenters so that the masses would be dissuaded from breaking the law. In the Roman Empire, crucifixions were usually carried out in public areas, especially near roads such as the Appian Way, where many would walk by to view the frightening power of the state.

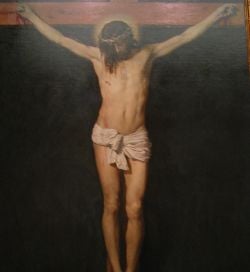

The most famous crucifixion in history is undoubtedly Jesus of Nazareth who was killed by the Romans for allegedly claiming to be the "King of the Jews," which ostensibly challenged the Roman Emperor's power and hegemony. Today, the most distinctive symbol of Roman Catholicism is the crucifix (an image of Christ crucified on a cross), while Protestant Christians usually prefer to use a cross without the figure (the "corpus" - Latin for "body") of Christ.

Etymology

The term "crucifixion" derives from the Late Latin crucifixionem (nominative crucifixio), noun of action from past-participle stem of crucifigere "to fasten to a cross." [1]

In Latin, a "crucifixion" applied to many different forms of painful execution, from impaling on a stake to affixing to a tree, to an upright pole (what some call a crux simplex) or to a combination of an upright (in Latin, stipes) and a crossbeam (in Latin, patibulum).[2]

Crucifixion was usually performed to provide a death that was particularly painful (hence the term excruciating, literally "out of crucifying"), gruesome (hence dissuading against the crimes punishable by it) and public, using whatever means were most expedient for that goal.

History of crucifixion

Pre-Roman States

Punishment by crucifixion was widely employed in ancient times, when it was considered one of the most brutal and shameful modes of death.[3] It was used systematically used by the Persians in the sixth century B.C.E.:

The first recorded instances of crucifixion are found in Persia, where it was believed that since the earth was sacred, the burial of the body of a notorious criminal would desecrate the ground. The birds above and the dogs below would dispose of the remains.[4] It was virtually never used in pre-Hellenic Greece.

Alexander the Great brought it to the eastern Mediterranean countries in the fourth century B.C.E., and the Phoenicians introduced it to Rome in the third century B.C.E. He is reputed to have executed 2000 survivors from his siege of the Phoenician city of Tyre, as well as the doctor who unsuccessfully treated Alexander's friend Hephaestion. Some historians have also conjectured that Alexander crucified Callisthenes, his official historian and biographer, for objecting to Alexander's adoption of the Persian ceremony of royal adoration.

In Carthage, crucifixion was an established mode of execution, which could even be imposed on a general for suffering a major defeat.

Roman Empire

According to some, the custom of crucifixion in Ancient Rome may have developed out of a primitive custom of arbori suspendere, hanging on an arbor infelix (unfortunate tree) dedicated to the gods of the nether world. However, the ideathat this punishment involved any form of hanging or was anything other than flogging to death, and the claim that the "arbor infelix" was dedicated to particular gods, was convincingly refuted.[5]

Tertullian mentions a first-century C.E. case in which trees were used for crucifixion,[6] However, Seneca the Younger earlier used the phrase infelix lignum (unfortunate wood) for the transom ("patibulum") or the whole cross.[7] According to others, the Romans appear to have learned of crucifixion from the Phoenicians in the third century B.C.E.[3]

Crucifixion was used for slaves, rebels, pirates and especially-despised enemies and criminals. Therefore crucifixion was considered a most shameful and disgraceful way to die. Condemned Roman citizens were usually exempt from crucifixion (like feudal nobles from hanging, dying more honorably by decapitation) except for major crimes against the state, such as high treason.

Notorious mass crucifixions followed the Third Servile War (the slave rebellion under Spartacus), the Roman Civil War, and the destruction of Jerusalem. Josephus tells a story of the Romans crucifying people along the walls of Jerusalem. He also says that the Roman soldiers would amuse themselves by crucifying criminals in different positions. In Roman-style crucifixion, the condemned took days to die slowly from suffocationâcaused by the condemned's blood-supply slowly draining away to a quantity insufficient to supply the required oxygen to vital organs. The dead body was left up for vultures and other birds to consume.

The goal of Roman crucifixion was not just to kill the criminal, but also to mutilate and dishonor the body of the condemned. In ancient tradition, an honorable death required burial; leaving a body on the cross, so as to mutilate it and prevent its burial, was a grave dishonor.

Crucifixion methods varied considerably with location and time period. If a crossbeam was used, the condemned man was forced to carry it on his shoulders, which would have been torn open by flagellation, to the place of execution.

The Roman historian Tacitus records that the city of Rome had a specific place for carrying out executions, situated outside the Esquiline Gate,[8] and had a specific area reserved for the execution of slaves by crucifixion.[9] Upright posts would presumably be fixed permanently in that place, and the crossbeam, with the condemned man perhaps already nailed to it, would then be attached to the post.

The person executed may sometimes have been attached to the cross by ropes, but nails were, as indicated not only by the New Testament accounts of the crucifixion of Jesus, but also in a passage of Josephus, where he mentions that, at the Siege of Jerusalem (70 C.E.), "the soldiers out of rage and hatred, nailed those they caught, one after one way, and another after another, to the crosses, by way of jest."[10]

Under ancient Roman penal practice, crucifixion was also a means of exhibiting the criminalâs low social status. It was the most dishonorable death imaginable, originally reserved for slaves, hence still called "supplicium servile" by Seneca, later extended to provincial freedmen of obscure station ('humiles'). The citizen class of Roman society were almost never subject to capital punishments; instead, they were fined or exiled. Josephus mentions Jews of high rank who were crucified, but this was to point out that their status had been taken away from them. Control of oneâs own body was vital in the ancient world. Capital punishment took away control over oneâs own body, thereby implying a loss of status and honor. The Romans often broke the prisoner's legs to hasten death and usually forbade burial.

A cruel prelude was scourging, which would cause the condemned to lose a large amount of blood, and approach a state of shock. The convict then usually had to carry the horizontal beam (patibulum in Latin) to the place of execution, but not necessarily the whole cross. Crucifixion was typically carried out by specialized teams, consisting of a commanding centurion and four soldiers. When it was done in an established place of execution, the vertical beam (stipes) could even be permanently embedded in the ground. The condemned was usually stripped naked - all the New Testament gospels, dated to around the same time as Josephus, describe soldiers gambling for the robes of Jesus. (Matthew 27:35, Mark 15:24, Luke 23:34, John 19:23-25)

The 'nails' were tapered iron spikes approximately 5 to 7 inch (13 to 18 cm) long, with a square shaft 3/8 inch (1 cm) across. In some cases, the nails were gathered afterwards and used as healing amulets.[11]

Emperor Constantine, the first Emperor thought to receive a Christian baptism, abolished crucifixion in the Roman Empire at the end of his reign. Thus, crucifixion was used by the Romans until about 313 C.E., when Christianity was legalized in the Roman Empire and soon became the official state religion.

Modern times

Crucifixion was used in Japan before and during the Tokugawa Shogunate. It was called Haritsuke in Japanese. The condemnedâusually a sentenced criminalâwas hoisted upon a T-shaped cross. Then, executioners finished him off with spear thrusts. The body was left to hang for a time before burial.

In 1597, it is recorded that 26 Christians were nailed to crosses at Nagasaki, Japan.[12] Among those executed were Paul Miki and Pedro Bautista, a Spanish Franciscan who had worked about ten years in the Philippines. The executions marked the beginning of a long history of persecution of Christianity in Japan, which continued until the end of World War II.

Since at least the mid-1800s, a group of Catholic flagellants in New Mexico called Hermanos de Luz ('Brothers of Light') have annually conducted reenactments of Jesus Christ's crucifixion during Holy Week, where a penitent is tiedâbut not nailedâto a cross.

Some very devout Catholics are voluntarily, non-lethally crucified for a limited time on Good Friday, to imitate the suffering of Jesus Christ. A notable example is the Passion Play, a ceremonial re-enactment of the crucifixion of Jesus, that has been performed yearly in the town of Iztapalapa, on the outskirts of Mexico City, since 1833.[13]

Devotional crucifixions are also common in the Philippines, even driving nails through the hands. One man named Rolando del Campo vowed to be crucified every Good Friday for 15 years if God would carry his wife through a difficult childbirth. In San Pedro Cutud, devotee Ruben Enaje has been crucified at least 21 times during Passion Week celebrations. In many cases the person portraying Jesus is previously subjected to flagellation (flailing) and wears a crown of thorns. Sometimes there is a whole passion play, sometimes only the mortification of the flesh.[14]

In the Fiftieth Session of the UN Commission on Human Rights (1994), local bishops reported several cases of crucifixion of Christian priests. Sudan's Penal Code, based upon the government's interpretation of Sharia, provides for execution by crucifixion.

Controversies

Cross shape

Crucifixion was carried out in many ways under the Romans. Josephus describes multiple positions of crucifixion during the siege of Jerusalem in 70 C.E. when Titus crucified the rebels;[10] and Seneca the Younger recounts: "I see crosses there, not just of one kind but made in many different ways: some have their victims with head down to the ground; some impale their private parts; others stretch out their arms on the gibbet."[2]

At times the gibbet was only one vertical stake, called in Latin crux simplex or palus. This was the most basic available construction for crucifying. Frequently, however, there was a cross-piece attached either at the top to give the shape of a T (crux commissa) or just below the top, as in the form most familiar in Christian symbolism (crux immissa). Other forms were in the shape of the letters X and Y.

The earliest writings that speak specifically of the shape of the cross on which Jesus died describe it as shaped like the letter T (the Greek letter tau). Some second-century writers took it for granted that a crucified person would have his arms stretched out, not connected to a single stake: Lucian speaks of Prometheus as crucified "above the ravine with his hands outstretched" and explains that the letter T (the Greek letter tau) was looked upon as an unlucky letter or sign (similar to the way the number 13 is looked upon today as an unlucky number), saying that the letter got its "evil significance" because of the "evil instrument" which had that shape, an instrument which tyrants hung men on.[15] Others described it as composed of an upright and a transverse beam, together with a small peg in the upright:

The very form of the cross, too, has five extremities, two in length, two in breadth, and one in the middle, on which [last] the person rests who is fixed by the nails.[16]

The oldest image of a crucifixion was found by archaeologists more than a century ago on the Palatine Hill in Rome:

It is a second-century graffiti scratched into a wall that was part of the imperial palace complex. It includes a caption - not by a Christian, but by someone taunting and deriding Christians and the crucifixions they underwent. It shows crude stick-figures of a boy reverencing his "God," who has the head of a jackass and is upon a cross with arms spread wide and with hands nailed to the crossbeam. Here we have a Roman sketch of a Roman crucifixion, and it is in the traditional cross shape.[15]

Location of the nails

In popular depictions of crucifixion (possibly derived from a literal reading of the Gospel of John's statement that Jesus' wounds were 'in the hands'),[17] the condemned is shown supported only by nails driven straight through the feet and the palms of the hands. This is possible only if the condemned was also tied to the cross by ropes, or if there was a foot-rest or a sedile to relieve the weight: on their own, the hands could not support the full body weight, because there are no structures in the hands to prevent the nails from ripping through the flesh due to the weight of the body.[18]

The scholarly consensus, however, is that the crucified were nailed through the wrists between the two bones of the forearm (the radius and the ulna) or in a space between four carpal bones rather than in the hands. A foot-rest attached to the cross, perhaps for the purpose of taking the man's weight off the wrists, is sometimes included in representations of the crucifixion of Jesus, but is not mentioned in ancient sources. These, however, do mention the sedile, a small seat attached to the front of the cross, about halfway down, which could have served that purpose. If the writings of Josephus are taken into account, a sedile was used at times as a way of impaling the "private parts." This would be achieved by resting the condemned man's weight on a peg or board of some sort, and driving a nail or spike through the genitals. If this was a common practice, then it would give credibility to accounts of crucified men taking days to die upon a cross, since the resting of the body upon a crotch peg or sedile would certainly prevent death by suspension asphyxiation. It would also provide another method of humiliation and great pain to the condemned.

Cause of death

The length of time required to reach death could range from a matter of hours to a number of days, depending on exact methods, the health of the crucified person and environmental circumstances.

Pierre Barbet holds that the typical cause of death was asphyxiation. He conjectured that when the whole body weight was supported by the stretched arms, the condemned would have severe difficulty inhaling, due to hyper-expansion of the lungs. The condemned would therefore have to draw himself up by his arms, or have his feet supported by tying or by a wood block. Indeed, Roman executioners could be asked to break the condemned's legs, after he had hung for some time, in order to hasten his death.[19] Once deprived of support and unable to lift himself, the condemned would die within a few minutes. If death did not come from asphyxiation, it could result from a number of other causes, including physical shock caused by the scourging that preceded the crucifixion, the nailing itself, dehydration, and exhaustion.

It was, however, possible to survive crucifixion, and there are records of people who did. The historian Josephus, a Judaean who defected to the Roman side during the Jewish uprising of 66 - 72 C.E., describes finding two of his friends crucified. He begged for and was granted their reprieve; one died, the other recovered. Josephus gives no details of the method or duration of crucifixion before their reprieve.

Archaeological evidence

Despite the fact that the ancient Jewish historian Josephus, as well as other sources, refer to the crucifixion of thousands of people by the Romans, there is only a single archaeological discovery of a crucified body dating back to the Roman Empire around the time of Jesus, which was discovered in Jerusalem. However, it is not surprising that there is only one such discovery, because a crucified body was usually left to decay on the cross and therefore would not be preserved. The only reason these archaeological remains were preserved was because family members gave this particular individual a customary burial.

The remains were found accidentally in an ossuary with the crucified manâs name on it, 'Yehohanan, the son of Hagakol'. The ossuary contained a heel with a nail driven through its side, indicating that the heels may have been nailed to the sides of the tree (one on the left side, one on the right side, and not with both feet together in front). The nail had olive wood on it indicating that he was crucified on a cross made of olivewood or on an olive tree. Since olive trees are not very tall, this would suggest that the condemned was crucified at eye level. Additionally, the piece of olive wood was located between the heel and the head of the nail, presumably to keep the condemned from freeing his foot by sliding it over the nail. His legs were found broken. (This is consistent with accounts of the execution of two thieves in the Gospel of St. John 19:31.) It is thought that since in Roman times iron was expensive, the nails were removed from the dead body to cut the costs, which would help to explain why only one has been found, as the back of the nail was bent in such a way that it could not be removed.

Other Details

Some Christian theologians, beginning with Saint Paul writing in Galatians 3:13, have interpreted an allusion to crucifixion in Deuteronomy 21:22-23. This reference is to being hanged from a tree, and may be associated with lynching or traditional hanging. However, ancient Jewish law allowed only 4 methods of execution: stoning, burning, strangulation, and decapitation. Crucifixion was thus forbidden by ancient Jewish law.[20]

Famous crucifixions

- Jesus of Nazareth, the best-known case of crucifixion, was condemned to crucifixion[21](most likely in 30 or 33 C.E.) by Pontius Pilate, the Roman governor of Judea. According to the New Testament, this was at the instigation of the Jewish leaders, who were scandalized at his claim to be the Messiah.

- The rebel slaves of the Third Servile War: Between 73 B.C.E. and 71 B.C.E. a band of slaves, eventually numbering about 120,000, under the (at least partial) leadership of Spartacus were in open revolt against the Roman Republic. The rebellion was eventually crushed, and while Spartacus himself most likely died in the final battle of the revolt, approximately 6000 of his followers were crucified along the 200 km road between Capua and Rome, as a warning to any other would-be rebels.

- Saint Peter, Christian apostle: according to tradition, Peter was crucified upside down at his own request (hence the "Cross of Saint Peter"), as he did not feel worthy to die the same way as Jesus (for he had denied him three times previously). Note that upside-down crucifixion would not result in death from asphyxiation.

- Saint Andrew, Christian apostle: according to tradition, crucified on an X-shaped cross, hence the name Saint Andrew's Cross.

- Simeon of Jerusalem, 2nd Bishop of Jerusalem, crucified either 106 or 107.

- Archbishop Joachim of Nizhny Novgorod: reportedly crucified upside down, on the Royal Doors of the Cathedral in Sevastopol, Ukrainian SSR in 1920.

- Wilgefortis was venerated as a saint and represented as a crucified woman, however her legend comes from a misinterpretation of the full-clothed crucifix of Lucca.

Crucifixion in popular culture

Many representations of crucifixion can still be found in popular culture in various mediums including cinema, sports, digital media, anime, and pop music, among others.

Crucifixion-type imagery is employed in several of the popular films, video games, music (and even professional wrestling!).

Movies dating back to the days of the silent films have depicted the crucifixion of Jesus. Most of these follow the traditional (and often inaccurate) pattern established by medieval and Renaissance artists, though there have been several notable exceptions. In The Passover Plot (1976) the two thieves are not shown to either side of Jesus but instead one is on a cross behind and facing him while the other is on a cross in front of and facing away from him. Ben-Hur (1959) may be the first Biblical movie to show the nails being driven through the wrists rather than the palms. It is also one of the first movies to show Jesus carrying just the crossbeam to Calvary rather than the entire cross. The Last Temptation of Christ is the first movie to show Jesus naked on the cross. In The Gospel of John (2003), Jesus' feet are shown being nailed through the ankle to each side of the upright portion of the cross. In The Passion of the Christ (2004), the crucifixion scene depicts Jesus's hands being impaled, and the centurions dislocating his shoulder in order to impale his right hand, and impaling his feet, and then turning the cross over to block the nails from coming out.

Notes

- â Crucifixion Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved February 21, 2019,

- â 2.0 2.1 Seneca the Younger, (Dialogue "To Marcia on Consolation," 6.20.3 The Latin Library. Retrieved February 21, 2019).

- â 3.0 3.1 F.P. Retief and L. Cilliers, The history and pathology of crucifixion South African Medical Journal 93(12) (2003):938-941. Retrieved February 21, 2019.

- â Damian Barry Smith, The Trauma of the Cross: How the Followers of Jesus Came to Understand the Crucifixion (Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 1999), 14.

- â William A. Oldfather, LIVY I.26 and the Supplicum de More Maiorum Transactions of the American Philological Association 39 (1908):49â72.

- â Apologia, IX, 1 Tertulliani Liber Apologeticus. Retrieved February 21, 2019.

- â After quoting a poem by Maecenas that speaks of preferring life to death even when life is burdened with all the disadvantages of old age or even with acute torture ("vel acuta si sedeam cruce"), Seneca disagrees with the sentiment, saying death would be better for a crucified person hanging from the patibulum: "I should deem him most despicable had he wished to live to the point of crucifixion âŠ. Is it worth so much to weigh down upon one's own wound, and hang stretched out from a patibulum? ⊠Is anyone found who, after being fastened to that accursed wood, already weakened, already deformed, swelling with ugly weals on shoulders and chest, with many reasons for dying even before getting to the cross, would wish to prolong a life-breath that is about to experience so many torments?" ("Contemptissimum putarem, si vivere vellet usque ad crucem ⊠Est tanti vulnus suum premere et patibulo pendere districtum ⊠Invenitur, qui velit adactus ad illud infelix lignum, iam debilis, iam pravus et in foedum scapularum ac pectoris tuber elisus, cui multae moriendi causae etiam citra crucem fuerant, trahere animam tot tormenta tracturam?" - Seneca the Younger, Letter 101, 12-14 The Latin Library. Retrieved February 21, 2019.

- â Tacitus, Annales 2:32.2 The Latin Library. Retrieved February 21, 2019.

- â Tacitus, Annales 15:60.1 The Latin Library. Retrieved February 21, 2019.

- â 10.0 10.1 Flavius Josephus, The Jewish War (Penguin Classics, 1984, ISBN 978-0140444209).

- â Mishna, Shabbath 6.10 Retrieved February 21, 2019.

- â James Kiefer, The Martyrs of Japan, February 5, 1597. The Lectionary. Retrieved February 21, 2019.

- â Larry Rohter, A Mexican Tradition Runs on Pageantry and Faith The New York Times, April 11, 2009. Retrieved February 21, 2019.

- â James Deakin, Images of Reenacted Crucifixions from the Philippines. (Warning: Some are graphic.) Retrieved February 21, 2019.

- â 15.0 15.1 Clayton F. Bower, Jr., Cross or Torture Stake? Catholic Answers, October 1, 1991. Retrieved February 21, 2019.

- â Irenaeus, Against Heresies (Book II, Chapter 24)) New Advent. Retrieved February 21, 2019.

- â The Gospel word ÏÎ”ÎŻÏ (cheir), translated as "hand," can include everything below the mid-forearm: Acts 12:7 uses this word to report chains falling off from Peter's 'hands', although the chains would be around what we would call wrists. This shows that the semantic range of ÏÎ”ÎŻÏ is wider than the English hand, and can be used of nails through the wrist.

- â Cahleen Shrier, The Science of the Crucifixion APU Life, Spring 2002, AZUZA Pacific University. Retrieved February 21, 2019.

- â John 19:31-32

- â See Mishnah, Sanhedrin 7:1, translated in Jacob Neusner, The Mishnah: A New Translation. 591 (1988), supra note 8, at 595-596 (indicating that court ordered execution by stoning, burning, decapitation, or strangulation only)

- â That this was the manner of his death is not only recounted in the four first-century canonical Gospels, but it is referred to repeatedly, as something well known, in the earlier letters of Saint Paul, for instance five times in his First Letter to the Corinthians, written in 57 C.E. (1:13, 1:18, 1:23, 2:2, 2:8). Pilate was the Roman governor at the time, and he is explicitly linked with the condemnation of Jesus not only by the Gospels but also by Tacitus, Annals', 15.44.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Hengel, Martin. Crucifixion. Augsburg Fortress, 1977. ISBN 080061268X

- Holoube, J.E., and A. B. Holoubek, "Execution by crucifixion." Journal of Medicine 26.

- Neusner, Jacob. The Mishnah: A New Translation. Yale University Press, 1991. ISBN 978-0300050226

- Smith, Damian Barry. The Trauma of the Cross: How the Followers of Jesus Came to Understand the Crucifixion. Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 1999. ISBN 978-0809139088

- Tzaferis, Vassilios. âCrucifixionâThe Archaeological Evidence.â Biblical Archaeology Review 11 (February, 1985): 44â53.

- Zias, Joseph. âThe Crucified Man from Givâat Ha-Mivtar: A Reappraisal.â Israel Exploration Journal 35(1) (1985): 22-27.

- This article incorporates text from the EncyclopĂŠdia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

External links

All links retrieved January 11, 2024.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.