Spanish Civil War

| Spanish Civil War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Combatants | |||||||

With the support of: |

|||||||

| Commanders | |||||||

| Manuel Azaña Francisco Largo Caballero Juan Negrín |

Francisco Franco | ||||||

| Casualties | |||||||

| Hundreds of thousands | |||||||

The Spanish Civil War, which lasted from July 17, 1936 to April 1, 1939, was a conflict in which the Francoists, or Nationalists, defeated the Republicans, or Loyalists, of the Second Spanish Republic. The Civil War devastated Spain, ending with the victory of the rebels and the founding of a dictatorship led by the Nationalist General Francisco Franco. The supporters of the Republic gained the support of the Soviet Union and Mexico, while the followers of the Rebellion received the support of the major European Axis powers of Italy and Germany. The United States remained officially neutral, but sold airplanes to the Republic and gasoline to the Francisco Franco regime.

The war started with military uprisings throughout Spain and its colonies. Republican sympathizers, soldiers, and civilians, formally acting independently of the state, massacred Catholic clergy and burned down churches, monasteries, and convents and other symbols of the Spanish Catholic Church which Republicans (especially the anarchists and communists) viewed as an oppressive institution supportive of the old order. The Republicans also attacked nobility, former landowners, rich farmers and industrialists. Intellectuals and working class men from other nations also joined the war. The former wanted to promote the cause of liberty and the socialist revolution, and aided the Republicans. The latter came more to escape post-Depression unemployment, and fought for either side. The presence of such literati as Ernest Hemingway and George Orwell ensured that the conflict would become immortalized in their writing.

The impact of the war was massive: The Spanish economy took decades to recover. The political and emotional repercussions of the war reverberated far beyond the boundaries of Spain and sparked passion among international intellectual and political communities, passions that still are present in Spanish politics today.

| Spanish Civil War |

|---|

| Alcázar – Gijón – Oviedo – Mérida – Mallorca – Badajoz – Sierra Guadalupe – Monte Pelato – Talavera – Cape Espartel – Madrid – Corunna Road – Málaga – Jarama – Guadalajara – Guernica – Bilbao – Brunete – Santander – Belchite – El Mazuco – Cape Cherchell – Teruel – Cape Palos – Ebro Chronology: 1936 1937 1938-39 |

Prelude

In the 1933 Spanish elections, the Spanish Confederation of the Autonomous Right(CEDA) won the most seats in the Cortes, but not enough to form a majority. President Niceto Alcalá Zamora refused to ask its leader, José María Gil-Robles, to form a government, and instead invited Alejandro Lerroux of the Radical Republican Party, a centrist party despite its name, to do so. CEDA supported the Lerroux government; it later demanded and, on October 1, 1934, received three ministerial positions. The Lerroux/CEDA government attempted to annul the social legislation that had been passed by the previous Manuel Azaña government, provoking general strikes in Valencia and Zaragoza, street conflicts in Madrid and Barcelona, and, on October 6, an armed miners' rebellion in Asturias and an autonomist rebellion in Catalonia. Both rebellions were suppressed, and were followed by mass political arrests and trials.

Lerroux's alliance with the right, his harsh repression of the revolt in 1934, and the Stra-Perlo scandal combined to leave him and his party with little support going into the 1936 election. (Lerroux himself lost his seat in parliament.)

As internal disagreements mounted in the coalition, strikes were frequent, and there were pistol attacks on unionists and clergy. In the elections of February 1936, the Popular Front won a majority of the seats in parliament. The coalition, which included the Socialist Party (PSOE), two liberal parties (the Republican Left Party of Manuel Azaña and the Republican Union Party), and Communist Party of Spain, as well as Galician and Catalan nationalists, received 34.3 percent of the popular vote, compared to 33.2 percent for the National Front parties led by CEDA.[1] The Basque nationalists were not officially part of the Front, but were sympathetic to it. The anarchist trade union Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT), which had sat out previous elections, urged its members to vote for the Popular Front in response to a campaign promise of amnesty for jailed leftists. The Socialist Party refused to participate in the new government. Its leader, Largo Caballero, hailed as "the Spanish Lenin" by Pravda, told crowds that revolution was now inevitable. Privately, however, he aimed merely at ousting the liberals and other non-socialists from the cabinet. Moderate Socialists like Indalecio Prieto condemned the left's May Day marches, clenched fists, and talk of revolution as insanely provocative.[2]

Without the Socialists, Prime Minister Manuel Azaña, a liberal who favored gradual reform while respecting the democratic process, led a minority government. In April, parliament replaced President Niceto Alcalá-Zamora, a moderate who had alienated virtually all the parties, with Azaña. Although the right also voted for Zamora's removal, this was a watershed event which inspired many conservatives to give up on parliamentary politics. Azaña was the object of intense hate by Spanish rightists, who remembered how he had pushed a reform agenda through a recalcitrant parliament in 1931-33. Joaquín Arrarás, a friend of Francisco Franco's, called him "a repulsive caterpillar of red Spain."[3] The Spanish generals particularly disliked Azaña because he had cut the army's budget and closed the military academy when he was war minister (1931). CEDA turned its campaign chest over to army plotter Emilio Mola. Monarchist José Calvo Sotelo replaced CEDA's Gil Robles as the right's leading spokesman in parliament. This was a period of rising tensions. Radicals became more aggressive, while conservatives turned to paramilitary and vigilante actions. According to official sources, 330 people were assassinated and 1,511 were wounded in politically-related violence; records show 213 failed assassination attempts, 113 general strikes, and the destruction of 160 religious buildings.

Deaths of Castillo & Calvo Sotelo

On July 12, 1936, José Castillo, a member of the Socialist Party and lieutenant in the Assault Guards, a special police corps created to deal with urban violence, was murdered by a far right group in Madrid. The following day, José Calvo Sotelo, the leader of the conservative opposition in the Cortes (Spanish parliament), was killed in revenge by Luis Cuenca, who was operating in a commando unit of the Civil Guard led by Captain Fernando Condés Romero. Calvo Sotelo was the most prominent Spanish monarchist and had protested against what he viewed as an escalating anti-religious terror, expropriations, and hasty agricultural reforms, which he considered Bolshevist and Anarchist. He instead advocated the creation of a corporative state and declared that if such a state was fascist, he was also a fascist.[4]

Nationalist military uprising

On July 17, 1936, the nationalist-traditionalist rebellion long feared by some in the Popular Front government, began. Its start was signaled by the phrase "Over all of Spain, the sky is clear" that was broadcast on the radio. Casares Quiroga, who had succeeded Azaña as prime minister, had in the previous weeks exiled the military officers suspected of conspiracy against the Republic, including General Manuel Goded y Llopis and General Francisco Franco, sent to the Balearic Islands and to the Canary Islands, respectively. Both generals immediately took control of these islands. Franco then flew to Spanish Morocco to see Juan March Ordinas, where the Nationalist Army of Africa were almost unopposed in assuming control. The rising was intended to be a swift coup d'etat, but was botched; conversely, the government was able to retain control of only part of the country. In this first stage, the rebels failed to take all major cities—in Madrid they were hemmed into the Montaña barracks. The barracks fell the next day with much bloodshed. In Barcelona, anarchists armed themselves and defeated the rebels. General Goded, who arrived from the Balearic islands, was captured and later executed. The anarchists would control Barcelona and much of the surrounding Aragonese and Catalan countryside for months. The Republicans held on to Valencia and controlled almost all of the Eastern Spanish coast and central area around Madrid. The Nationalists took most of the northwest, apart from Asturias, Cantabria, and the Basque Country and a southern area including Cádiz, Huelva, Sevilla, Córdoba, and Granada; resistance in some of these areas led to reprisals.

Factions in the war

The active participants in the war covered the entire gamut of the political positions and ideologies of the time. The Nationalist side included the Carlists and Legitimist monarchists, Spanish nationalists, fascists of the Falange, Catholics, and most conservatives and monarchist liberals. On the Republican side were Basque and Catalan nationalists, socialists, communists, liberals, and anarchists.

To view the political alignments from another perspective, the Nationalists included the majority of the Catholic clergy and of practicing Catholics (outside of the Basque region), important elements of the army, most of the large landowners, and many businessmen. The Republicans included most urban workers, most peasants, and much of the educated middle class, especially those who were not entrepreneurs. The genial monarchist General José Sanjurjo was figurehead of the rebellion, while Emilio Mola was chief planner and second in command. Mola began serious planning in the spring, but General Francisco Franco hesitated until early July. Franco was a key player because of his prestige as a former director of the military academy and the man who suppressed the Socialist uprising of 1934. Warned that a military coup was imminent, leftists put barricades up on the roads on July 17. Franco avoided capture by taking a tugboat to the airport. From there, he flew to Morocco, where he took command of the battle-hardened colonial army. Sanjurjo was killed in a plane crash on July 20, leaving effective command split between Mola in the north and Franco in the South. Franco was chosen overall commander at a meeting of ranking generals at Salamanca on September 21. He outranked Mola and by this point his Army of Africa had demonstrated its military superiority.

One of the Nationalists' principal claimed motives was to confront the anticlericalism of the Republican regime and to defend the Roman Catholic Church, which was censured for its support for the monarchy, which many on the Republican side blamed for the ills of the country. In the opening days of the war, religious buildings were burnt without action on the part of the Republican authorities to prevent it. Similarly, many of the massacres perpetrated by the Republican side targeted the Catholic Clergy. Franco's religious Moroccan Muslim troops found this repulsive and, for the most part, fought loyally and often ferociously for the Nationalists. Articles 24 and 26 of the Constitution of the Republic had banned the Jesuits, which deeply offended many of the Nationalists. After the beginning of the Nationalist coup, anger flared anew at the Church and its role in Spanish politics. Notwithstanding these religious matters, the Basque nationalists, who nearly all sided with the Republic, were, for the most part, practicing Catholics. John Paul II later canonized several priests and nuns, murdered for their affiliation with the Church.[5]

Foreign involvement

The rebellion was opposed by the government (with the troops that remained loyal to the Republic), as well as by the vast majority of urban workers, who were often members of Socialist, Communist, and anarchist groups.

The British government proclaimed itself neutral; however, the British ambassador to Spain, Sir Henry Chilton, believed that a victory for Franco was in Britain's best interests and worked to support the Nationalists. British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden publicly maintained the official policy of non-intervention, but privately expressed his desire that the Republicans win the war. Britain also discouraged activity by its citizens supporting either side. The Anglo-French arms embargo meant that the Republicans' only foreign source of material was the USSR, while the Nationalists received weapons from Italy and Germany and logistical support from Portugal. The last Republican prime minister, Juan Negrín, hoped that a general outbreak of war in Europe would compel the European powers (mainly Britain and France) to finally help the republic, but World War II would not commence until months after the Spanish conflict had ended. Ultimately, neither Britain nor France intervened to any significant extent. Britain supplied food and medicine to the Republic, but actively discouraged the French government of Léon Blum from supplying weapons.

Both Italy under Mussolini and Germany under Hitler violated the embargo and sent troops (Corpo Truppe Volontarie and Condor Legion), aircraft, and weapons to support Franco. The Italian contribution amounted to over 60,000 troops at the height of the war, and the involvement helped to increase Mussolini's popularity among Italian Catholics, as the latter had remained highly critical of their ex-Socialist fascist Duce. Italian military help to Nationalists against the anti-clerical and anti-Catholic atrocities committed by the Republican side, worked well in Italian propaganda targeting Catholics. On July 27, 1936, the first squadron of Italian airplanes sent by Benito Mussolini arrived in Spain. Some speculate that Hitler used the Spanish Civil War issue to distract Mussolini from his own designs on, and plans for, Austria (Anschluss), as the authoritarian Catholic, anti-Nazi Väterländische Front government of autonomous Austria had been in alliance with Mussolini, and in 1934, during the assassination of Austria's authoritarian president Engelbert Dollfuss had already successfully invoked Italian military assistance in case of a Nazi German invasion.

In addition, there were a few volunteer troops from other nations who fought with the Nationalists, such as some Irish Blueshirts under Eoin O'Duffy, and the French Croix de Feu. Although these volunteers, primarily Catholics, came from around the world (including Ireland, Brazil, and the U.S.), there were fewer of them and they are not as famous as those fighting on the Republican side, and were generally less organized and hence embedded in Nationalist units whereas many Republican units were comprised entirely of foreigners.

Due to the Franco-British arms embargo, the Government of the Republic could receive material aid and could purchase arms only from the Soviet Union. These arms included 1,000 aircraft, 900 tanks, 1,500 artillery pieces, 300 armored cars, hundreds of thousands of small arms, and 30,000 tons of ammunition (some of which was defective). To pay for these armaments the Republicans used U.S. dollars 500 million in gold reserves. At the start of the war, the Bank of Spain had the world's fourth largest reserve of gold, about U.S. dollars 750 million,[6] although some assets were frozen by the French and British governments. The Soviet Union also sent more than 2,000 personnel, mainly tank crews and pilots, who actively participated in combat, on the Republican side.[7] Nevertheless, some have contended that the Soviet government was motivated by the desire to sell arms and that they charged exorbitant prices.[8] Later, the "Moscow gold" was an issue during the Spanish transition to democracy. They have also been accused of prolonging the war because Stalin knew that Britain and France would never accept a communist government. Though Stalin did call for the repression of Republican elements that were hostile to the Soviet Union (for example, the anti-Stalininst POUM), he also made a conscious effort to limit Soviet involvement in the struggle and silence its revolutionary aspects in an attempt to remain on good diplomatic terms with the French and British.[9] Mexico also aided the Republicans by providing rifles and food. Throughout the war, the efforts of the elected government of the Republic to resist the rebel army were hampered by Franco-British "non-intervention," long supply lines, and intermittent availability of weapons of widely variable quality.

Volunteers from many countries fought in Spain, most of them on the Republican side. 60,000 men and women fought in the International Brigades, including the American Abraham Lincoln Brigade and Canadian Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion, organized in close conjunction with the Comintern to aid the Spanish Republicans. Others fought as members of the CNT and POUM militias. Those fighting with POUM most famously included George Orwell and the small ILP Contingent.

"Spain" became the cause célèbre for the left-leaning intelligentsia across the Western world, and many prominent artists and writers entered the Republic's service. As well, it attracted a large number of foreign left-wing working class men, for whom the war offered not only idealistic adventure but also an escape from post-Depression unemployment. Among the more famous foreigners participating on the Republic's side were Ernest Hemingway and George Orwell, who went on to write about his experiences in Homage to Catalonia. Orwell's novel, Animal Farm, was loosely inspired by his experiences and those of other members of POUM, at the hands of Stalinists, when the Popular Front began to fight within itself, as were the torture scenes in 1984. Hemingway's novel, For Whom the Bell Tolls, was inspired by his experiences in Spain. The third part of Laurie Lee's autobiographical trilogy, (A Moment of War) is also based on his Civil War experiences (though the accuracy of some of his recollections has been disputed). Norman Bethune used the opportunity to develop the special skills of battlefield medicine. As a casual visitor, Errol Flynn used a fake report of his death at the battlefront to promote his movies. Despite the predominantly leftist attitude of the artistic community, several prominent writers, such as Ezra Pound, Roy Campbell, Gertrude Stein, and Evelyn Waugh, sided with Franco.

The United States was isolationist, neutralist, and was little concerned with what it largely saw as an internal matter in a European country. Nevertheless, from the outset the Nationalists received important support from some elements of American business. The American-owned Vacuum Oil Company in Tangier, for example, refused to sell to Republican ships and the Texas Oil Company supplied gasoline on credit to Franco until the war's end. While not supported officially, many American volunteers, such as the Abraham Lincoln Battalion fought for the Republicans. Many in these countries were also shocked by the violence practiced by anarchist and POUM militias—and reported by a relatively free press in the Republican zone—and feared Stalinist influence over the Republican government. Reprisals, assassinations, and other atrocities in the rebel zone were, of course, not reported nearly as widely.

Germany and the USSR used the war as a testing ground for faster tanks and aircraft that were just becoming available at the time. The Messerschmitt Bf-109 fighter and Junkers Ju-52 transport/bomber were both used in the Spanish Civil War. The Soviets provided Polikarpov I-15 and Polikarpov I-16 fighters. The Spanish Civil War was also an example of total war, where the killing of civilians, such as the bombing of the Basque town of Gernika by the Legión Cóndor, as depicted by Pablo Picasso in the painting Guernica, foreshadowed episodes of World War II, such as the bombing campaign on Britain by the Nazis and the bombing of Dresden or Hamburg by the Allies.

War

The war: 1936

In the early days of the war, over 50,000 people who were caught on the "wrong" side of the lines were assassinated or summarily executed. The numbers were probably comparable on both sides. In these paseos ("promenades"), as the executions were called, the victims were taken from their refuges or jails by armed people to be shot outside of town. Probably the most famous such victim was the poet and dramatist, Federico García Lorca. The outbreak of the war provided an excuse for settling accounts and resolving long-standing feuds. Thus, this practice became widespread during the war in areas conquered. In most areas, even within a single given village, both sides committed assassinations.

Any hope of a quick ending to the war was dashed on July 21, the fifth day of the rebellion, when the Nationalists captured the main Spanish naval base at Ferrol in northwestern Spain. This encouraged the Fascist nations of Europe to help Franco, who had already contacted the governments of Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy the day before. On July 26, the future Axis Powers cast their lot with the Nationalists. Nationalist forces under Franco won another great victory on September 27, when they relieved the Alcázar at Toledo.

A Nationalist garrison under Colonel Moscardo had held the Alcázar in the center of the city since the beginning of the rebellion, resisting for months against thousands of Republican troops who completely surrounded the isolated building. The inability to take the Alcázar was a serious blow to the prestige of the Republic, as it was considered inexplicable in view of their numerical superiority in the area. Two days after relieving the siege, Franco proclaimed himself Generalísimo and Caudillo ("chieftain"), while forcibly unifying the various Falangist and Royalist elements of the Nationalist cause. In October, the Nationalists launched a major offensive toward Madrid, reaching it in early November and launching a major assault on the city on November 8. The Republican government was forced to shift from Madrid to Valencia, out of the combat zone, on November 6. However, the Nationalists' attack on the capital was repulsed in fierce fighting between November 8 and 23. A contributory factor in the successful Republican defense was the arrival of the International Brigades, though only around 3000 of them participated in the battle. Having failed to take the capital, Franco bombarded it from the air and, in the following two years, mounted several offensives to try to encircle Madrid.

On November 18, Germany and Italy officially recognized the Franco regime, and on December 23, Italy sent "volunteers" of its own to fight for the Nationalists.

The war: 1937

With his ranks being swelled by Italian troops and Spanish colonial soldiers from Morocco, Franco made another attempt to capture Madrid in January and February of 1937, but failed again.

On February 21, the League of Nations Non-Intervention Committee ban on foreign national "volunteers" went into effect. The large city of Málaga was taken on February 8. On March 7, German Condor Legion equipped with Heinkel He-51 biplanes arrived in Spain; on April 26, they bombed the town of Guernica (Gernika) in the Basque Country; two days later, Franco's men entered the town.

After the fall of Guernica, the Republican government began to fight back with increasing effectiveness. In July, they made a move to recapture Segovia, forcing Franco to pull troops away from the Madrid front to halt their advance. Mola, Franco's second-in-command, was killed on June 3, and in early July, despite the fall of Bilbao in June, the government actually launched a strong counter-offensive in the Madrid area, which the Nationalists repulsed only with some difficulty. The clash was called "Battle of Brunete."

Franco soon regained momentum, invading Aragon in August and then taking the city of Santander (now in Cantabria). On August 28, the Vatican, possibly under pressure from Mussolini, recognized the Franco government. Two months of bitter fighting followed and, despite determined Asturian resistance, Gijón (in Asturias) fell in late October, effectively ending the war in the North. At the end of November, with the Nationalists closing in on Valencia, the government moved again, to Barcelona.

The war: 1938

The battle of Teruel was an important confrontation between Nationalists and Republicans. The city belonged to the Republicans at the beginning of the battle, but the Nationalists conquered it in January. The Republican government launched an offensive and recovered the city, however the Nationalists finally conquered it for good by February 22. On April 14, the Nationalists broke through to the Mediterranean Sea, cutting the government-held portion of Spain in two. The government tried to sue for peace in May, but Franco demanded unconditional surrender, and the war raged on.

The government now launched an all-out campaign to reconnect their territory in the Battle of the Ebro, beginning on July 24 and lasting until November 26. The campaign was militarily successful, but was fatally undermined by the Franco-British appeasement of Hitler in Munich. The concession of Czechoslovakia destroyed the last vestiges of Republican morale by ending all hope of an anti-fascist alliance with the great powers. The retreat from the Ebro all but determined the final outcome of the war. Eight days before the new year, Franco struck back by throwing massive forces into an invasion of Catalonia.

The war: 1939

The Nationalists conquered Catalonia in a whirlwind campaign during the first two months of 1939. Tarragona fell on January 14, followed by Barcelona on January 26, and Girona on February 5. Five days after the fall of Girona, the last resistance in Catalonia was broken.

On February 27, the governments of the United Kingdom and France recognized the Franco regime.

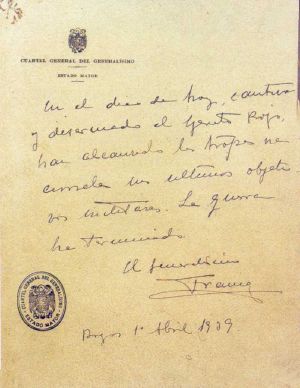

Only Madrid and a few other strongholds remained for the government forces. On March 28, with the help of pro-Franco forces inside the city (the "fifth column" General Mola had mentioned in propaganda broadcasts in 1936), Madrid fell to the Nationalists. The next day, Valencia, which had held out under the guns of the Nationalists for close to two years, also surrendered. Victory was proclaimed on April 1, when the last of the Republican forces surrendered.

After the end of the War, there were harsh reprisals against Franco's former enemies on the left, when thousands of Republicans were imprisoned and between 10,000 and 28,000 executed. Many other Republicans fled abroad, especially to France and Mexico.

Social revolution

In the anarchist-controlled areas, Aragon and Catalonia, in addition to the temporary military success, there was a vast social revolution in which the workers and the peasants collectivized land and industry, and set up councils parallel to the paralyzed Republican government. This revolution was opposed by both the Soviet-supported communists, who ultimately took their orders from Stalin's politburo (which feared a loss of control), and the Social Democratic Republicans (who worried about the loss of civil property rights). The agrarian collectives had considerable success despite opposition and lack of resources, as Franco had already captured lands with some of the richest natural resources.

As the war progressed, the government and the communists were able to leverage their access to Soviet arms to restore government control over the war effort, both through diplomacy and force. Anarchists and the POUM (Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista) were integrated with the regular army, albeit with resistance; the POUM was outlawed and falsely denounced as an instrument of the fascists. In the May Days of 1937, many hundreds or thousands of anti-fascist soldiers fought one another for control of strategic points in Barcelona, recounted by George Orwell in Homage to Catalonia.

Notes

- ↑ Spartacus, 1936 Elections. Retrieved August 19, 2007.

- ↑ History Today, Spain 1936: From Coup d'Etat to Civil War.

- ↑ History Today, Franco and Azaña.

- ↑ Hugh Thomas, The Spanish Civil War Penguin (London: 2003). ISBN 0141011610

- ↑ Faith Web, General Index MARTYRS OF THE RELIGIOUS PERSECUTION DURING THE SPANISH CIVIL WAR (X 1934, 36-39). Retrieved August 19, 2007.

- ↑ Spartacus, Soviet Union. Retrieved August 19, 2007.

- ↑ One Party, The Soviet Union and the Spanish Civil War. Retrieved August 19, 2007.

- ↑ Blackened Flag, How Moscow robbed Spain of its gold in the Civil War. Retrieved August 19, 2007.

- ↑ Paul Preston, The Spanish Civil War, 1936-39 (New York: Grove Press, 1986). ISBN 9780394555652

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Alpert, Michael. New International History of the Spanish Civil War. Basingstoke, 2004. ISBN 1403911711

- Beevor, Antony. The Spanish Civil War. London: Penguin, 2001. ISBN 0141001488

- Brenan, Gerald. The Spanish Labyrinth: An Account of the Social and Political Background of the Civil War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990. ISBN 0521398274

- Graham, Helen. The Spanish Republic at War, 1936-1939. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002. ISBN 052145932X

- Howson, Gerald. Arms for Spain. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1998. ISBN 0312241771

- Jackson, Gabriel. The Spanish Republic and the Civil War, 1931-1939. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1965. ISBN 0691007578

- Koestler, Arthur. Dialogue with Death. London: Macmillan, 1983. ISBN 0333347765

- Malraux, André. L'Espoir (Man's Hope). New York: Modern Library, 1941. ISBN 0394604784

- Payne, Stanley. The Spanish Civil War, the Soviet Union, and Communism. London: Yale University Press, 2004. ISBN 030010068X

- Preston, Paul. The Coming of the Spanish Civil War. London: Macmillan, 1978. ISBN 0333237242

- Puzzo, Dante Anthony. Spain and the Great Powers, 1936-1941. Freeport, NY: Books for Libraries Press, 1962. ISBN 0836968689

- Radosh, Ronald. Spain Betrayed: The Soviet Union in the Spanish Civil War. London: Yale University Press, 2001. ISBN 0-300-08981-3

- Thomas, Hugh. The Spanish Civil War. London: Penguin, 2003. ISBN 0141011610

- Walters, Guy. Berlin Games—How Hitler Stole the Olympic Dream. New York: HarperCollins, 2006. ISBN 0719567831

External links

All links retrieved February 7, 2023.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.