League of Nations

| League of Nations | |

|

| |

|

| |

| Formation | June 28, 1919 |

|---|---|

| Extinction | April 18, 1946 |

| Headquarters | Palais des Nations, Geneva |

| Membership | 63 member states |

| Official languages | French, English, Spanish |

| Secretary General | Seán Lester (most recent) |

The League of Nations was an international organization founded as a result of the Paris Peace Conference in 1919‚Äď1920. The League's goals included disarmament, preventing war through collective security, settling disputes between countries through negotiation, diplomacy and improving global welfare. The diplomatic philosophy behind the League represented a fundamental shift in thought from the preceding hundred years. The League lacked an armed force of its own and so depended on the Great Powers to enforce its resolutions, keep to economic sanctions which the League ordered, or provide an army, when needed, for the League to use. However, they were often very reluctant to do so. Benito Mussolini stated that "The League is very well when sparrows shout, but no good at all when eagles fall out."

After a number of notable successes and some early failures in the 1920s, the League ultimately proved incapable of preventing aggression by the Axis Powers in the 1930s. The onset of the Second World War suggested that the League had failed in its primary purpose‚Äďto avoid any future world war. The United Nations Organization replaced it after the end of the war and inherited a number of agencies and organizations founded by the League.

Origins

A predecessor of the League of Nations in many respects were the international Hague Conventions (1899 and 1907). The "Hague Confederation of States" as the Neo-Kantian pacifist Walther Sch√ľcking called it, formed a universal alliance aiming at disarmament and the peaceful settlement of disputes through arbitration. The concept of a peaceful community of nations had previously been described in Immanuel Kant‚Äôs Perpetual Peace: A Philosophical Sketch (1795). Following the failure of the Hague Peace Conferences - a third conference had been planned for 1915 - the idea of the actual League of Nations appears to have originated with British Foreign Secretary Edward Grey, and it was enthusiastically adopted by the Democratic United States President Woodrow Wilson and his advisor Colonel Edward M. House as a means of avoiding bloodshed like that of World War I. The creation of the League was a centerpiece of Wilson's Fourteen Points for Peace, specifically the final point: "A general association of nations must be formed under specific covenants for the purpose of affording mutual guarantees of political independence and territorial integrity to great and small states alike."

The Paris Peace Conference accepted the proposal to create the League of Nations (French: Société des Nations, German: Völkerbund) on January 25, 1919. The Covenant of the League of Nations was drafted by a special commission, and the League was established by Part I of the Treaty of Versailles, which was signed on June 28, 1919. Initially, the Charter was signed by 44 states, including 31 states which had taken part in the war on the side of the Triple Entente or joined it during the conflict. Despite Wilson's efforts to establish and promote the League, for which he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1919, the United States neither ratified the Charter nor joined the League due to opposition in the U.S. Senate, especially influential Republicans Henry Cabot Lodge of Massachusetts and William E. Borah of Idaho, together with Wilson's refusal to compromise.

The League held its first meeting in London on January 10, 1920. Its first action was to ratify the Treaty of Versailles, officially ending World War I. The headquarters of the League moved to Geneva on November 1, 1920, where the first general assembly of the League was held on November 15, 1920 with representatives from 41 nations in attendance.

David Kennedy, a professor at Harvard Law School, examined the League through the scholarly texts surrounding it, the establishing treaties, and voting sessions of the plenary. Kennedy suggests the League is a unique moment when international affairs was "institutionalized", as opposed to the pre-World War I methods of law and politics[1].

Symbols

The League of Nations had neither an official flag nor logo. Proposals for adopting an official symbol were made during the League's beginning in 1921, but the member states never reached agreement. However, League of Nations organizations used varying logos and flags (or none at all) in their own operations. An international contest was held in 1929 to find a design, which again failed to produce a symbol. One of the reasons for this failure may have been the fear by the member states that the power of the supranational organization might supersede them. Finally, in 1939, a semi-official emblem emerged: two five-pointed stars within a blue pentagon. The pentagon and the five-pointed stars were supposed to symbolize the five continents and the five races of mankind. In a bow on top and at the bottom, the flag had the names in English (League of Nations) and French (Société des Nations). This flag was used on the building of the New York World's Fair in 1939 and 1940.

Languages

The official languages of the League of Nations were French, English and Spanish (from 1920). In 1921, there was a proposal by the Under-Secretary General of the League of Nations, Dr. Nitobe InazŇć, for the League to accept Esperanto as their working language. Ten delegates accepted the proposal with only one voice against, the French delegate, Gabriel Hanotaux. Hanotaux did not like it that the French language was losing its position as the international language of diplomacy and saw Esperanto as a threat. Two years later the League recommended that its member states include Esperanto in their educational curricula.

Structure

The League had three principal organs: a secretariat (headed by the General Secretary and based in Geneva), a Council, and an Assembly. The League also had numerous Agencies and Commissions. Authorization for any action required both a unanimous vote by the Council and a majority vote in the Assembly.

Secretariat and Assembly

The staff of the League's secretariat was responsible for preparing the agenda for the Council and Assembly and publishing reports of the meetings and other routine matters, effectively acting as the civil service for the League.

Secretaries-general of League of Nations (1920 ‚Äď 1946)

¬†United Kingdom Sir James Eric Drummond, 7th Earl of Perth (1920‚Äď1933)

¬†United Kingdom Sir James Eric Drummond, 7th Earl of Perth (1920‚Äď1933) ¬†France Joseph Avenol (1933‚Äď1940)

¬†France Joseph Avenol (1933‚Äď1940) ¬†Ireland Se√°n Lester (1940‚Äď1946)

¬†Ireland Se√°n Lester (1940‚Äď1946)

Each member was represented and had one vote in the League Assembly. Individual member states did not always have representatives in Geneva. The Assembly held its sessions once a year in September.

Presidents of General Assembly of League (1920‚Äď1946)

¬†Belgium Paul Hymans (1st time) 1920‚Äď1921

¬†Belgium Paul Hymans (1st time) 1920‚Äď1921 ¬†Netherlands Herman Adriaan van Karnebeek 1921‚Äď1922

¬†Netherlands Herman Adriaan van Karnebeek 1921‚Äď1922 ¬†Chile Agustin Edwards 1922‚Äď1923

¬†Chile Agustin Edwards 1922‚Äď1923 ¬†Cuba Cosme de la Torriente y Peraza 1923‚Äď1924

¬†Cuba Cosme de la Torriente y Peraza 1923‚Äď1924 ¬†Switzerland Giuseppe Motta 1924‚Äď1925

¬†Switzerland Giuseppe Motta 1924‚Äď1925 ¬†Canada Raoul Dandurand 1925‚Äď1926

¬†Canada Raoul Dandurand 1925‚Äď1926 ¬†Portugal Afonso Augusto da Costa 1926‚Äď1926

¬†Portugal Afonso Augusto da Costa 1926‚Äď1926 ¬†Yugoslavia Momńćilo Ninńćińá ) 1926‚Äď1927

¬†Yugoslavia Momńćilo Ninńćińá ) 1926‚Äď1927 ¬†Uruguay Alberto Guani 1927‚Äď1928

¬†Uruguay Alberto Guani 1927‚Äď1928 ¬†Denmark Herluf Zahle 1928‚Äď1929

¬†Denmark Herluf Zahle 1928‚Äď1929 ¬†El Salvador Jose Gustavo Guerrero 1929‚Äď1930

¬†El Salvador Jose Gustavo Guerrero 1929‚Äď1930 Kingdom of Romania Nicolae Titulescu 1930‚Äď1932

Kingdom of Romania Nicolae Titulescu 1930‚Äď1932 ¬†Belgium Paul Hymans (2nd time) 1932‚Äď1933

¬†Belgium Paul Hymans (2nd time) 1932‚Äď1933 Union of South Africa Charles Theodore Te Water 1933‚Äď1934

Union of South Africa Charles Theodore Te Water 1933‚Äď1934 ¬†SwedenRichard Johannes Sandler 1934

¬†SwedenRichard Johannes Sandler 1934 ¬†Mexico Francisco Castillo Najera 1934‚Äď1935

¬†Mexico Francisco Castillo Najera 1934‚Äď1935 ¬†Czechoslovakia Edvard BeneŇ° 1935‚Äď1936

¬†Czechoslovakia Edvard BeneŇ° 1935‚Äď1936 ¬†Argentina Carlos Saavedra Lamas 1936‚Äď1937

¬†Argentina Carlos Saavedra Lamas 1936‚Äď1937 ¬†Turkey Tevfik Rustu Aras 1937‚Äď1937

¬†Turkey Tevfik Rustu Aras 1937‚Äď1937 British Raj Sir Muhammad Shah Aga Khan 1937‚Äď1938

British Raj Sir Muhammad Shah Aga Khan 1937‚Äď1938 ¬†Ireland Eamon de Valera 1938‚Äď1939

¬†Ireland Eamon de Valera 1938‚Äď1939 ¬†Norway Carl Joachim Hambro 1939‚Äď1946

¬†Norway Carl Joachim Hambro 1939‚Äď1946

Council

The league Council had the authority to deal with any matter affecting world peace. The Council began with four permanent members (the United Kingdom, France, Italy, Japan) and four non-permanent members, which were elected by the Assembly for a three-year period. The first four non-permanent members were Belgium, Brazil, Greece and Spain. The United States was meant to be the fifth permanent member, but the United States Senate was dominated by the Republican Party after the 1918 election and voted on March 19, 1920 against the ratification of the Treaty of Versailles, thus preventing American participation in the League. The rejection of the treaty was part of a shift in policy away from engagement toward a return to the policies of isolationism that had characterized the pre-war period.

The initial composition of the Council was subsequently changed a number of times. The number of non-permanent members was first increased to six on September 22, 1922, and then to nine on September 8, 1926. Germany also joined the League and became a fifth permanent member of the Council on the latter date, taking the Council to a total of 15 members. When Germany and Japan later both left the League, the number of non-permanent seats was eventually increased from nine to eleven. The Council met on average five times a year, and in extraordinary sessions when required. In total, 107 public sessions were held between 1920 and 1939.

Other bodies

The League oversaw the Permanent Court of International Justice and several other agencies and commissions created to deal with pressing international problems. These were the Disarmament Commission, the Health Organization, the International Labor Organization, the Mandates Commission, the Permanent Central Opium Board, the Commission for Refugees, and the Slavery Commission. While the League itself is generally branded a failure, several of its Agencies and Commissions had successes within their respective mandates.

- Disarmament Commission

- The Commission obtained initial agreement by France, Italy, Japan, and Britain to limit the size of their navies. However, the United Kingdom refused to sign a 1923 disarmament treaty, and the Kellogg-Briand Pact, facilitated by the commission in 1928, failed in its objective of outlawing war. Ultimately, the Commission failed to halt the military buildup during the 1930s by Germany, Italy and Japan.

- Health Committee

- This body focused on ending leprosy, malaria and yellow fever, the latter two by starting an international campaign to exterminate mosquitoes. The Health Organization also succeeded in preventing an epidemic of typhus from spreading throughout Europe due to its early intervention in the Soviet Union.

- Mandates Commission

- The Commission supervised League of Nations Mandates, and also organized plebiscites in disputed territories so that residents could decide which country they would join, most notably the plebiscite in Saarland in 1935.

- International Labor Organization

- This body was led by Albert Thomas. It successfully banned the addition of lead to paint, and convinced several countries to adopt an eight-hour work day and 48-hour working week. It also worked to end child labor, increase the rights of women in the workplace, and make shipowners liable for accidents involving seamen.

- Permanent Central Opium Board

- The Board was established to supervise the statistical control system introduced by the second International Opium Convention that mediated the production, manufacture, trade and retail of opium and its by-products. The Board also established a system of import certificates and export authorizations for the legal international trade in narcotics.

- Commission for Refugees

- Led by Fridtjof Nansen, the Commission oversaw the repatriation and, when necessary the resettlement, of 400,000 refugees and ex-prisoners of war, most of whom were stranded in Russia at the end of World War I. It established camps in Turkey in 1922 to deal with a refugee crisis in that country and to help prevent disease and hunger. It also established the Nansen passport as a means of identification for stateless peoples.

- Slavery Commission

- The Commission sought to eradicate slavery and slave trading across the world, and fought forced prostitution and drug trafficking, particularly in opium. It succeeded in gaining the emancipation of 200,000 slaves in Sierra Leone and organized raids against slave traders in its efforts to stop the practice of forced labor in Africa. It also succeeded in reducing the death rate of workers constructing the Tanganyika railway from 55 percent to 4 percent. In other parts of the world, the Commission kept records on slavery, prostitution and drug trafficking in an attempt to monitor those issues.

- Committee for the Study of the Legal Status of Women

- This committee sought to make an inquiry into the status of women all over the world. Formed in April 1938, dissolved in early 1939. Committee members included Mme. P. Bastid (France), M. de Ruelle (Belgium), Mme. Anka Godjevac (Yugoslavia), Mr. HC Gutteridge (United Kingdom), Mlle. Kerstin Hesselgren (Sweden), Ms. Dorothy Kenyon (United States), M. Paul Sebastyen (Hungary) and Secretariat Mr. McKinnon Wood (Great Britain).

Several of these institutions were transferred to the United Nations after the Second World War. In addition to the International Labour Organisation, the Permanent Court of International Justice became a UN institution as the International Court of Justice, and the Health Organization was restructured as the World Health Organization.

Members

See main article on League of Nations members

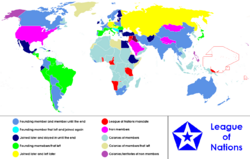

The League of Nations had 42 founding members excluding United States of America, 16 of them left or withdrew from the international organization. The Kingdom of Yugoslavia was the only (founding) member to leave the league and return to it later and remained so a member until the end. In the founding year six other states joined, only two of them would have a membership that lasted until the end. In later years 15 more countries joined, three memberships would not last until the end. Egypt was the last state to join in 1937. The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics was expelled from the league on December 14, 1939 five years after it joined on September 18, 1934. Iraq was the only member of the league that at one time was a League of Nations Mandate. Iraq became a member in 1932.

Mandates

League of Nations Mandates were established under Article 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations. These territories were former colonies of the German Empire and the Ottoman Empire that were placed under the supervision of the League following World War I. There were three Mandate classifications:

- "A" Mandate

- This was a territory which "had reached a stage of development where their existence as independent nations can be provisionally recognized, subject to the rendering of administrative advice and assistance by a "Mandatory" until such time as they are able to stand alone. The wishes of these communities must be a principal consideration in the selection of the Mandatory." These were mainly parts of the old Ottoman Empire.

- "B" Mandate

- This was a territory which "was at such a stage that the Mandatory must be responsible for the administration of the territory under conditions which will guarantee:

- Freedom of conscience and religion

- The maintenance of public order and morals

- Prohibition of abuses such as the slave trade, the arms traffic and the liquor traffic

- The prevention of the establishment of fortifications or military and naval bases and of military training of the natives for other than political purposes and the defence of territory

- Equal opportunities for the trade and commerce of other Members of the League."

- "C" Mandate

- This was a territory "which, owing to the sparseness of their population, or their small size, or their remoteness from the centres of civilisation, or their geographical contiguity to the territory of the Mandatory, and other circumstances, can be best administered under the laws of the Mandatory."

(Quotations taken from The Essential Facts About the League of Nations, a handbook published in Geneva in 1939).

The territories were governed by "Mandatory Powers," such as the United Kingdom in the case of the Mandate of Palestine and the Union of South Africa in the case of South-West Africa, until the territories were deemed capable of self-government. There were fourteen mandate territories divided up among the six Mandatory Powers of the United Kingdom, France, Belgium, New Zealand, Australia and Japan. In practice, the Mandatory Territories were treated as colonies and were regarded by critics as spoils of war. With the exception of Iraq, which joined the League on October 3, 1932, these territories did not begin to gain their independence until after the Second World War, a process that did not end until 1990. Following the demise of the League, most of the remaining mandates became United Nations Trust Territories.

In addition to the Mandates, the League itself governed the Saarland for 15 years, before it was returned to Germany following a plebiscite, and the free city of Danzig (now GdaŇĄsk, Poland) from November 15, 1920 to September 1, 1939.

Successes

The League is generally considered to have failed in its mission to achieve disarmament, prevent war, settle disputes through diplomacy, and improve global welfare. However, it achieved significant successes in a number of areas.

√Öland Islands

√Öland is a collection of around 6,500 islands mid-way between Sweden and Finland. The islands are exclusively Swedish-speaking, but Finland had sovereignty in the early 1900s. During the period from 1917 onwards, most residents wished the islands to become part of Sweden; Finland, however, did not wish to cede the islands. The Swedish government raised the issue with the League in 1921. After close consideration, the League determined that the islands should remain a part of Finland, but be governed autonomously, averting a potential war between the two countries.

Albania

The border between Albania and the Kingdom of Yugoslavia remained in dispute after the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, and Yugoslavian forces occupied some Albanian territory. After clashes with Albanian tribesmen, the Yugoslav forces invaded farther. The League sent a commission of representatives from various powers to the region. The commission found in favor of Albania, and the Yugoslav forces withdrew in 1921, albeit under protest. War was again prevented.

Austria and Hungary

Following the First World War, Austria and Hungary were facing bankruptcy due to high war reparation payments. The League arranged loans for the two nations and sent commissioners to oversee the spending of this money. These actions started Austria and Hungary on the road to economic recovery.

Upper Silesia

The Treaty of Versailles had ordered a plebiscite in Upper Silesia to determine whether the territory should be part of Germany or Poland. In the background, strong-arm tactics and discrimination against Poles led to rioting and eventually to the first two Silesian Uprisings (1919 and 1920). In the plebiscite, roughly 59.6 percent percent (around 500,000) of the votes were cast for joining Germany, and this result led to the Third Silesian Uprising in 1921. The League was asked to settle the matter. In 1922, a six-week investigation found that the land should be split; the decision was accepted by both countries and by the majority of Upper Silesians.

Memel

The port city of Memel (now Klaipńóda) and the surrounding area was placed under League control after the end of the World War I and was governed by a French general for three years. Although the population was mostly German, the Lithuanian government placed a claim to the territory, with Lithuanian forces invading in 1923. The League chose to cede the land around Memel to Lithuania, but declared the port should remain an international zone; Lithuania agreed. While the decision could be seen as a failure (in that the League reacted passively to the use of force), the settlement of the issue without significant bloodshed was a point in the League's favor.

Greece and Bulgaria

After an incident between sentries on the border between Greece and Bulgaria in 1925, Greek troops invaded their neighbor. Bulgaria ordered its troops to provide only token resistance, trusting the League to settle the dispute. The League did indeed condemn the Greek invasion, and called for both Greek withdrawal and compensation to Bulgaria. Greece complied, but complained about the disparity between their treatment and that of Italy (see Corfu, below).

Saar

Saar was a province formed from parts of Prussia and the Rhenish Palatinate that was established and placed under League control after the Treaty of Versailles. A plebiscite was to be held after 15 years of League rule, to determine whether the region should belong to Germany or France. 90.3 percent of votes cast were in favor of becoming part of Germany in that 1935 referendum, and it became part of Germany again.

Mosul

The League resolved a dispute between Iraq and Turkey over the control of the former Ottoman province of Mosul in 1926. According to the UK, which was awarded a League of Nations A-mandate over Iraq in 1920 and therefore represented Iraq in its foreign affairs, Mosul belonged to Iraq; on the other hand, the new Turkish republic claimed the province as part of its historic heartland. A three person League of Nations committee was sent to the region in 1924 to study the case and in 1925 recommended the region to be connected to Iraq, under the condition that the UK would hold the mandate over Iraq for another 25 years, to assure the autonomous rights of the Kurdish population. The League Council adopted the recommendation and it decided on 16 December 1925 to award Mosul to Iraq. Although Turkey had accepted the League of Nations arbitration in the Treaty of Lausanne in 1923, it rejected the League's decision. Nonetheless, Britain, Iraq and Turkey made a treaty on June 25, 1926, that largely mirrored the decision of the League Council and also assigned Mosul to Iraq.

Liberia

Following rumors of forced labor in the independent African country of Liberia, the League launched an investigation into the matter, particularly the alleged use of forced labor on the massive Firestone rubber plantation in that country. In 1930, a report by the League implicated many government officials in the selling of contract labor, leading to the resignation of President Charles D.B. King, his vice-president and numerous other government officials. The League followed with a threat to establish a trusteeship over Liberia unless reforms were carried out, which became the central focus of President Edwin Barclay.

Other successes

The League also worked to combat the international trade in opium and sexual slavery and helped alleviate the plight of refugees, particularly in Turkey in the period to 1926. One of its innovations in this area was its 1922 introduction of the Nansen passport, which was the first internationally recognized identity card for stateless refugees. Many of the League's successes were accomplished by its various Agencies and Commissions.

General Weaknesses

The League did not succeed in the long term. The outbreak of World War II was the immediate cause of the League's demise, but there outbreak of the war exposed a variety of other, more fundamental, flaws.

The League, like the modern United Nations, lacked an armed force of its own and depended on the Great Powers to enforce its resolutions, which they were very reluctant to do. Economic sanctions, which were the most severe measure the League could implement short of military action, were difficult to enforce and had no great impact on the target country, because they could simply trade with those outside the League. The problem is exemplified in the following passage, taken from The Essential Facts About the League of Nations, a handbook published in Geneva in 1939:

"As regards the military sanctions provided for in paragraph 2 of Article 16, there is no legal obligation to apply them… there may be a political and moral duty incumbent on states… but, once again, there is no obligation on them."

The League's two most important members, Britain and France, were reluctant to use sanctions and even more reluctant to resort to military action on behalf of the League. So soon after World War I, the populations and governments of the two countries were pacifist. The British Conservatives were especially tepid on the League and preferred, when in government, to negotiate treaties without the involvement of the organization. Ultimately, Britain and France both abandoned the concept of collective security in favor of appeasement in the face of growing German militarism under Adolf Hitler.

Representation at the League was often a problem. Though it was intended to encompass all nations, many never joined, or their time as part of the League was short. In January 1920 when the League began, Germany was not permitted to join, due to its role in World War I. Soviet Russia was also banned from the League, as their communist views were not welcomed by the Western powers after World War I. The greatest weakness of the League, however, was that the United States never joined. Their absence took away much of the League's potential power. Even though US President Woodrow Wilson had been a driving force behind the League's formation, the United States Senate voted on November 19, 1919 not to join the League.

The League also further weakened when some of the main powers left in the 1930s. Japan began as a permanent member of the Council, but withdrew in 1933 after the League voiced opposition to its invasion of the Chinese territory of Manchuria. Italy also began as a permanent member of the Council but withdrew in 1937. The League did accepted Germany as a member in 1926, deeming it a "peace-loving country," but Adolf Hitler pulled Germany out when he came to power in 1933.

Another major power, the Bolshevik Soviet Union, became a member only in 1934, when it joined to antagonize Nazi Germany (which had left the year before), but left December 14, 1939, when it was expelled for aggression against Finland. In expelling the Soviet Union, the League broke its own norms. Only 7 out of 15 members of the Council voted for the expelling (Great Britain, France, Belgium, Bolivia, Egypt, South African Union and the Dominican Republic), which was not a majority of votes as was required by the Charter. Three of these members were chosen as members of the Council the day before the voting (South African Union, Bolivia and Egypt).[2] The League of Nations practically ceased functioning after that and was formally dismissed in 1946.[3]

The League's neutrality tended to manifest itself as indecision. The League required a unanimous vote of its nine-(later 15-)member-Council to enact a resolution, so conclusive and effective action was difficult, if not impossible. It was also slow in coming to its decisions. Some decisions also required unanimous consent of the Assembly; that is, agreement by every member of the League.

Another important weakness of the League was that while it sought to represent all nations, most members protected their own national interests and were not committed to the League or its goals. The reluctance of all League members to use the option of military action showed this to the full. If the League had shown more resolve initially, countries, governments and dictators may have been more wary of risking its wrath in later years. These failings were, in part, among the reasons for the outbreak of World War II.

Moreover, the League's advocacy of disarmament for Britain and France (and other members) while at the same time advocating collective security meant that the League was unwittingly depriving itself of the only forceful means by which its authority would be upheld. This was because if the League was to force countries to abide by international law it would primarily be the Royal Navy and the French Army which would do the fighting. Furthermore, Britain and France were not powerful enough to enforce international law across the globe, even if they wished to do so. For its members, League obligations meant there was a danger that states would get drawn into international disputes which did not directly affect their respective national interests.

On June 23, 1936, in the wake of the collapse of League efforts to restrain Italy's war of conquest against Abyssinia, British Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin told the House of Commons that collective security "failed ultimately because of the reluctance of nearly all the nations in Europe to proceed to what I might call military sanctions…. The real reason, or the main reason, was that we discovered in the process of weeks that there was no country except the aggressor country which was ready for war…. [I]f collective action is to be a reality and not merely a thing to be talked about, it means not only that every country is to be ready for war; but must be ready to go to war at once. That is a terrible thing, but it is an essential part of collective security." It was an accurate assessment and a lesson which clearly was applied in the formation of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, which stood as the League's successor insofar as its role as guarantor of the security of Western Europe was concerned.

Specific Failures

The general weaknesses of the League are illustrated by its specific failures.

Cieszyn, 1919

Cieszyn (German Teschen, Czech TńõŇ°√≠n) is a region between Poland and today's Czech Republic, important for its coal mines. Czechoslovakian troops moved to Cieszyn in 1919 to take over control of the region while Poland was defending itself from invasion of Bolshevik Russia. The League intervened, deciding that Poland should take control of most of the town, but that Czechoslovakia should take one of the town's suburbs, which contained the most valuable coal mines and the only railroad connecting Czech lands and Slovakia. The city was divided into Polish Cieszyn and Czech ńĆesk√Ĺ TńõŇ°√≠n. Poland refused to accept this decision; although there was no further violence, the diplomatic dispute continued for another 20 years.

Vilna, 1920

After World War I, Poland and Lithuania both regained the independence that they had lost during the partitions of Lithuanian-Polish Commonwealth in 1795. Though both countries shared centuries of common history in the Polish-Lithuanian Union and Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, rising Lithuanian nationalism prevented the recreation of the former federated state. The city of Vilna (Lithuanian Vilnius, Polish Wilno) was made the capital of Lithuania. Although Vilnius had been the cultural and political center of Grand Duchy of Lithuania since 1323, it happened so that the majority of the population in twentieth century was Polish.

During the Polish-Soviet War in 1920, a Polish army took control of the city. Despite the Poles' claim to the city, the League chose to ask Poland to withdraw: the Poles did not. The city and its surroundings were proclaimed a separate state of Central Lithuania and on 20 February 1922 the local parliament passed the Unification Act and the city was incorporated into Poland as the capital of the Wilno Voivodship. Theoretically, British and French troops could have been asked to enforce the League's decision; however, France did not wish to antagonize Poland, which was seen as a possible ally in a future war against Germany or the Soviet Union, while Britain was not prepared to act alone. Both Britain and France also wished to have Poland as a 'buffer zone' between Europe and the possible threat from Communist Russia. Eventually, the League accepted Wilno as a Polish town on March 15, 1923. Thus the Poles were able to keep it until Soviet invasion in 1939.

Lithuanian authorities declined to accept the Polish authority over Vilna and treated it as a constitutional capital. It was not until the 1938 ultimatum, when Lithuania resolved diplomatic relations with Poland and thus de facto accepted the borders of its neighbor.

Invasion of the Ruhr Valley, 1923

Under the Treaty of Versailles, Germany had to pay war reparations. They could pay in money or in goods at a set value; however, in 1922 Germany was not able to make its payment. The next year, France and Belgium chose to take action, invading the industrial heartland of Germany, the Ruhr, despite the fact that action was a direct violation of the League's rules. Since France was a major League member, and Britain was hesitant to oppose its close ally, no sanctions were forthcoming. This set a significant precedent‚Äďthe League rarely acted against major powers, and occasionally broke its own rules.

Corfu, 1923

One major boundary settlement that remained to be made after World War I was that between Greece and Albania. The Conference of Ambassadors, a de facto body of the League, was asked to settle the issue. The Council appointed Italian general Enrico Tellini to oversee this. On August 27, 1923, while examining the Greek side of the border, Tellini and his staff were murdered. Italian leader Benito Mussolini was incensed, and demanded the Greeks pay reparations and execute the murderers. The Greeks, however, did not actually know who the murderers were.

On August 31, Italian forces occupied the island of Corfu, part of Greece, and 15 people were killed. Initially, the League condemned Mussolini's invasion, but also recommended Greece pay compensation, to be held by the League until Tellini's killers were found. Mussolini, though he initially agreed to the League's terms, set about trying to change them. By working with the Council of Ambassadors, he managed to make the League change its decision. Greece was forced to apologize and compensation was to be paid directly and immediately. Mussolini was able to leave Corfu in triumph. By bowing to the pressure of a large country, the League again set a dangerous and damaging example. This was one of the League's major failures.

Mukden Incident, 1931‚Äď1933

The Mukden Incident was one of the League's major setbacks and acted as the catalyst for Japan's withdrawal from the organization. In the Mukden Incident, also known as the "Manchurian Incident," the Japanese held control of the South Manchurian Railway in the Chinese region of Manchuria. They claimed that Chinese soldiers had sabotaged the railway, which was a major trade route between the two countries, on September 18, 1931. In fact, it is thought that the sabotage had been contrived by officers of the Japanese Kwantung Army without the knowledge of government in Japan, in order to catalyze a full invasion of Manchuria. In retaliation, the Japanese army, acting contrary to the civilian government's orders, occupied the entire region of Manchuria, which they renamed Manchukuo. This new country was recognized internationally by only Italy and Germany‚Äďthe rest of the world still saw Manchuria as legally a region of China. In 1932, Japanese air and sea forces bombarded the Chinese city of Shanghai and the short war of January 28 Incident broke out.

The Chinese government asked the League of Nations for help, but the long voyage around the world by sailing ship for League officials to investigate the matter themselves delayed matters. When they arrived, the officials were confronted with Chinese assertions that the Japanese had invaded unlawfully, while the Japanese claimed they were acting to keep peace in the area. Despite Japan's high standing in the League, the Lytton Report declared Japan to be in the wrong and demanded Manchuria be returned to the Chinese. However, before the report was voted upon by the Assembly, Japan announced intentions to invade more of China. When the report passed 42-1 in the Assembly in 1933 (only Japan voted against), Japan withdrew from the League.

According to the Covenant of the League of Nations, the League should have now placed economic sanctions against Japan, or gathered an army together and declared war against it. However, neither happened. Economic sanctions had been rendered almost useless due to the United States Congress voting against being part of the League, despite Woodrow Wilson's keen involvement in drawing up the Treaty of Versailles and his wish that America to join the League. Any economic sanctions the League now placed on its member states would be fairly pointless, as the state barred from trading with other member states could simply turn and trade with America. An army was not assembled by the League due to the self-interest of many of its member states. This meant that countries like Britain and France did not want to gather together an army for the League to use as they were too interested and busy with their own affairs‚Äďsuch as keeping control of their extensive colonial lands, especially after the turmoil of World War I. Japan was therefore left to keep control of Manchuria, until the Red Army of the Soviet Union took over the area and returned it to China at the end of World War II in 1945.

Chaco War, 1932-1935

The League failed to prevent the Chaco War between Bolivia and Paraguay in 1932 over the arid Gran Chaco region of South America. Although the region was sparsely populated, it gave control of the Paraguay River which would have given one of the two landlocked countries access to the Atlantic Ocean, and there was also speculation, later proved incorrect, that the Chaco would be a rich source of petroleum. Border skirmishes throughout the late 1920s culminated in an all-out war in 1932, when the Bolivian army, following the orders of President Daniel Salamanca Urey, attacked a Paraguayan garrison at Vanguardia. Paraguay appealed to the League of Nations, but the League did not take action when the Pan-American conference offered to mediate instead.

The war was a disaster for both sides, causing 100,000 casualties and bringing both countries to the brink of economic disaster. By the time a ceasefire was negotiated on June 12, 1935, Paraguay had seized control over most of the region. This was recognized in a 1938 truce by which Paraguay was awarded three-quarters of the Chaco Boreal.

Italian invasion of Abyssinia, 1935‚Äď1936

Perhaps most famously, in October 1935, Benito Mussolini sent General Pietro Badoglio and 400,000 troops to invade Abyssinia (Ethiopia). The modern Italian Army easily defeated the poorly armed Abyssinians, and captured Addis Ababa in May 1936, forcing Emperor Haile Selassie to flee. The Italians used chemical weapons (mustard gas) and flame throwers against the Abyssinians.

The League of Nations condemned Italy's aggression and imposed economic sanctions in November 1935, but the sanctions were largely ineffective. As Stanley Baldwin, the British Prime Minister, later observed, this was ultimately because no one had the military forces on hand to withstand an Italian attack. On October 9, 1935, the United States under President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (a non-League member) refused to cooperate with any League action. It had embargoed exports of arms and war material to either combatant (in accordance with its new Neutrality Act) on October 5 and later (February 29, 1936) endeavored (with uncertain success) to limit exports of oil and other materials to normal peacetime levels. The League sanctions were lifted on July 4, 1936, but by that point they were a dead letter in any event.

In December 1935, the Hoare-Laval Pact was an attempt by the British Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs Hoare and the French Prime Minister Laval to end the conflict in Abyssinia by drawing up a plan to partition Abyssinia into two parts‚Äďan Italian sector and an Abyssinian sector. Mussolini was prepared to agree to the Pact however news of the Pact was leaked and both the British and French public venomously protested against the Pact describing it as a sell-out of Abyssinia. Hoare and Laval were forced to resign their positions and both the British and French government disassociated with them respectively.

As was the case with Japan, the vigor of the major powers in responding to the crisis in Abyssinia was tempered by their perception that the fate of this poor and far-off country, inhabited by non-Europeans, was not vital to their national interests.

Spanish Civil War, 1936‚Äď1939

On July 17, 1936, armed conflict broke out between Spanish Republicans (the left-wing government of Spain) and Nationalists (the right-wing rebels, including most officers of the Spanish Army). Alvarez del Vayo, the Spanish minister of foreign affairs, appealed to the League in September 1936 for arms to defend its territorial integrity and political independence. However, the League could not itself intervene in the Spanish Civil War nor prevent foreign intervention in the conflict. Hitler and Mussolini continued to aid General Franco’s Nationalist insurrectionists, and the Soviet Union aided the Spanish loyalists. The League did attempt to ban the intervention of foreign national volunteers.

Axis re-armament

The League was powerless and mostly silent in the face of major events leading to World War II such as Hitler's remilitarization of the Rhineland, occupation of the Sudetenland and Anschluss of Austria, which had been forbidden by the Treaty of Versailles. As with Japan, both Germany in 1933‚ÄĒusing the failure of the World Disarmament Conference to agree to arms parity between France and Germany as a pretext‚ÄĒand Italy in 1937 simply withdrew from the League rather than submit to its judgment. The League commissioner in Danzig was unable to deal with German claims on the city, a significant contributing factor in the outbreak of World War II in 1939. The final significant act of the League was to expel the Soviet Union in December 1939 after it invaded Finland.

Demise and Legacy

The final meeting of the League of Nations was held in Geneva on April 18, 1946. Delegates from 34 nations attended, and a motion was made to close the session, with the resolution that "The League of Nations shall cease to exist except for the purpose of the liquidation of its assets." The vote was 33-0 in favor, with Egypt abstaining. At 5:43 P.M. Geneva time, Secretary Carl J. Hambro of Norway stated, "I declare the twenty-first and last session of the General Assembly of the League of Nations closed." [4].

With the onset of World War II, it had been clear that the League had failed in its purpose‚Äďto avoid any future world war. During the war, neither the League's Assembly nor Council had been able or willing to meet, and its secretariat in Geneva had been reduced to a skeleton staff, with many offices moving to North America. At the 1945 Yalta Conference, the Allied Powers agreed to create a new body to supplant the League's role. This body was to be the United Nations. Many League bodies, such as the International Labor Organization, continued to function and eventually became affiliated with the UN. The League's assets of $22,000,000 were then assigned to the U.N.

The structure of the United Nations was intended to make it more effective than the League. The principal Allies in World War II (UK, USSR, France, U.S., and China) became permanent members of the UN Security Council, giving the new "Great Powers" significant international influence, mirroring the League Council. Decisions of the UN Security Council are binding on all members of the UN; however, unanimous decisions are not required, unlike the League Council. Permanent members of the UN Security Council were given a shield to protect their vital interests, which has prevented the UN acting decisively in many cases. Similarly, the UN does not have its own standing armed forces, but the UN has been more successful than the League in calling for its members to contribute to armed interventions, such as the Korean War, and peacekeeping in the former Yugoslavia. However, the UN has in some cases been forced to rely on economic sanctions. The UN has also been more successful than the League in attracting members from the nations of the world, making it more representative.

See also

- League of Nations members

- Henry Cabot Lodge, U.S. Republican Senator who led the opposition to the U.S. joining the League

- Palais des Nations, built as the League's headquarters.

- Article X of the Covenant of the League of Nations was, according to U.S. Republican Senators, one of the most objectionable parts of the League of Nations and a major reason for its rejection in the US

- Treaty of Versailles

- United Nations

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ David Kennedy, "The Move to Institutions," Cardozo Law Review 8 (1987): 841-988. Reprinted in International Organization, Jan Klabbers, ed. (Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2006)

- ‚ÜĎ Igor Pychalov. Velikaja obolgannaja vojna.

- ‚ÜĎ –õ–ł–≥–į –Ĺ–į—Ü–ł–Ļ –õ–ł–≥–į –Ĺ–į—Ü–ł–Ļ - Retrieved October 23, 2007.

- ‚ÜĎ "League of Nations Ends, Gives Way to New U.N.," Syracuse Herald-American, April 20, 1946, 12

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- The Essential Facts About the League of Nations. Geneva, Information Section, 1938. OCLC 2103446

- Bassett, John Spencer. The League of Nations: A Chapter in World Politics. New York; London; [etc.] Longmans, Green and Co., 1928. OCLC 735138

- Egerton, George W. Great Britain and the Creation of the League of Nations: Strategy, Politics, and International Organization, 1914‚Äď1919. University of North Carolina Press, 1978. ISBN 9780807813201

- Gill, George. 1996. The League of Nations from 1929 to 1946: From 1929 to 1946. Avery Publishing Group. ISBN 0895296373.

- Kelly, Nigel and Greg Lacey. Modern World History. Oxford: Heinemann Educational, 2001. ISBN 9780435308308

- Kennedy, David, "The Move to Institutions" 8 Cardozo Law Review 841 (1987). Reprinted in J. Klabbers, ed. International Organization. Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2006.

- Kennedy, David, "The Move to Institutions," Cardozo Law Review 8 (1987): 841-988. Reprinted in International Organization, Jan Klabbers, editor, Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2006.

- Kennedy, Paul. The Parliament of Man: The Past, Present, and Future of the United Nations. New York: Random House, 2006. ISBN 9780375501654

- Kuehl, Warren F. and Lynne K. Dunn. Keeping the Covenant: American Internationalists and the League of Nations, 1920‚Äď1939. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press, 1997. ISBN 9780585246154.

- League of Nations chronology, Retrieved 21 January 2006.

- Malin, James C. The United States after the World War. Ginn & Company, 1930. online1930. pp 5‚Äď82 questia.com.Retrieved November 12, 2008.

- Marbeau, M. 2001. "La Société des Nations." Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. ISBN 2130516351. (in French)

- Northedge, F. S. The League of Nations: Its Life and Times, 1920‚Äď1946. Teaneck, NJ: Holmes & Meier. 1986. ISBN 9780841910652

- Pfeil, A. 1976. "Der Völkerbund."

- Walters, F. P. A History of the League of Nations. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1986. ISBN 9780313250569.

- Walsh, Ben. 1997. Modern World History. John Murray (Publishers) Ltd.. ISBN 0719572312.

- Zimmern, Alfred. The League of Nations and the Rule of Law, 1918‚Äď1935. 1936. OCLC 60263987

External links

All links retrieved March 11, 2025.

- Woodrow Wilson's Fourteen Points. byu.edu

- Covenant of the League of Nations, yale.edu

- League of Nations Factmonster

- Map of League of Nations members

- League of Nations Chronology World at War

- Wilson's Final Address in Support of the League of Nations Speech made 25 September 1919

- League of Nations History Learning Site

| |||||||

| World War I | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General | Main events | Specific articles | Participants | See also |

|

Prelude:

Theatres:

General timeline:

See also:

|

1914:

1915:

1916:

1917:

1918:

|

Civilian impact and atrocities:

Aftermath:

|

Entente Powers

¬†¬†¬Ľ ¬†¬†¬Ľ

Central Powers

|

Contemporaneous conflicts:

|

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.