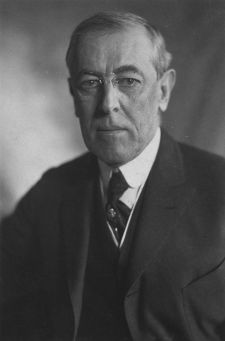

Woodrow Wilson

| Term of office | March 4, 1913 â March 3, 1921 |

| Preceded by | William Howard Taft |

| Succeeded by | Warren G. Harding |

| Date of birth | December 28, 1856 |

| Place of birth | Staunton, Virginia |

| Date of death | February 3, 1924 |

| Place of death | Washington, D.C. |

| Spouse | Ellen Louise Axson |

| Political party | Democrat |

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856 â February 3, 1924) was the 28th President of the United States (1913â1921). A devout Presbyterian, he became a noted historian and political scientist. As a reform Democrat, he was elected as the governor of New Jersey in 1910 and as president in 1912. His first term as president resulted in major legislation including the Underwood-Simmons tariff and the creation of the Federal Trade Commission and the Federal Reserve System. Wilson was a popular president, and the American people elected him to a second term, a term that centered on World War I and his efforts afterward to shape the post-war world through the Treaty of Versailles.

In September 1919, during a nation-wide trip undertaken to sell the treaty to the American people, Wilson suffered a debilitating stroke. Months of rest led to partial recovery, but Wilson was never the same. Ultimately, with the president in no shape to negotiate a compromise, the isolationist-minded U.S. Senate twice refused to ratify the Treaty of Versailles. Woodrow Wilson finished out his second term with his wife serving as what amounted to a "fill-in" president. He died in 1924.

Early Life, Education, and Family

Thomas Woodrow Wilson was born of Scotch-Irish ancestry in Staunton, Virginia in 1856, as the third of four children to Rev. Dr. Joseph Ruggles Wilson and Janet Mary Woodrow. Wilson's grandparents immigrated to the U.S. from Strabane, County Tyrone, in modern-day Northern Ireland. Wilson spent the majority of his childhood, to age 14, in Augusta, Georgia, where his father was minister of the First Presbyterian Church. He lived in the state capital Columbia, South Carolina from 1870 to 1874, where his father was professor at the Presbyterian Theological Seminary. Wilson's father was originally from Ohio where his grandfather had been an abolitionist and his uncles were Republicans. His parents moved south in 1851 and identified with the Confederacy during the war. There, they owned slaves and set up a Sunday school for them. Wilson's parents cared for wounded Confederate soldiers at their church.

Wilson experienced difficulty in reading, which may have indicated dyslexia, but he taught himself shorthand to compensate and was able to achieve academically through determination and self-discipline. His mother homeschooled him, and he attended Davidson College for one year before transferring to Princeton College of New Jersey at Princeton (now Princeton University), graduating in 1879. Afterward, he studied law at the University of Virginia and practiced briefly in Atlanta. He pursued doctoral study in social science at the new Johns Hopkins University. After completing and publishing his dissertation, Congressional Government, in 1886, Wilson received his doctorate in political science.

Political Writings

Wilson came of age in the decades after the American Civil War, when Congress was supremeâ"the gist of all policy is decided by the legislature"âand corruption was rampant. Instead of focusing on individuals in explaining where American politics went wrong, Wilson focused on the American constitutional structure (Wilson 2006, 180).

Under the influence of Walter Bagehot's The English Constitution, Wilson viewed the United States Constitution as pre-modern, cumbersome, and open to corruption. An admirer of the English parliamentary system from afarâhe first visited London in 1919âWilson favored a similar system for the United States. Wilson wrote the following in the early 1880s:

I ask you to put this question to yourselves, should we not draw the Executive and Legislature closer together? Should we not, on the one hand, give the individual leaders of opinion in Congress a better chance to have an intimate party in determining who should be president, and the president, on the other hand, a better chance to approve himself a statesman, and his advisers capable men of affairs, in the guidance of Congress? (Wilson 1956, 41â48).

Although Wilson began writing Congressional Government, his best known political work, as an argument for a parliamentary system, Grover Cleveland's strong presidency altered his viewpoint. Congressional Government emerged as a critical description of America's system, with frequent negative comparisons to Westminster. Wilson himself claimed, "I am pointing out factsâdiagnosing, not prescribing, remedies" (Wilson 2006, 205).

Wilson believed that America's intricate system of checks and balances was the cause of the problems in American governance. He said that the divided power made it impossible for voters to see who was accountable for poor policy and economic crises. If government behaved badly, Wilson asked,

âŠhow is the schoolmaster, the nation, to know which boy needs the whipping?⊠Power and strict accountability for its use are the essential constituents of good government.⊠It is, therefore, manifestly a radical defect in our federal system that it parcels out power and confuses responsibility as it does. The main purpose of the Constitutional Convention of 1787 seems to have been to accomplish this grievous mistake. The âliterary theoryâ of checks and balances is simply a consistent account of what our Constitution makers tried to do; and those checks and balances have proved mischievous just to the extent which they have succeeded in establishing themselves⊠[the Framers] would be the first to admit that the only fruit of dividing power had been to make it irresponsible (Wilson 2006, 186â87).

In the section of Congressional Government that concerns the United States House of Representatives, Wilson heaps scorn on the seniority-based committee system. Power, Wilson wrote, "is divided up, as it were, into forty-seven signatories, in each of which a Standing Committee is the court baron and its chairman lord proprietor. These petty barons, some of them not a little powerful, but none of them within reach [of] the full powers of rule, may at will exercise an almost despotic sway within their own shires, and may sometimes threaten to convulse even the realm itself" (Wilson 2006, 76). Wilson said that the committee system was fundamentally undemocratic, because committee chairs, who ruled by seniority, were responsible to no one except their constituents, even though they determined national policy.

In addition to its undemocratic nature, Wilson also believed that the Committee System facilitated corruption:

âŠthe voter, moreover, feels that his want of confidence in Congress is justified by what he hears of the power of corrupt lobbyists to turn legislation to their own uses. He hears of enormous subsidies begged and obtainedâŠof appropriations made in the interest of dishonest contractors; he is not altogether unwarranted in the conclusion that these are evils inherent in the very nature of Congress; there can be no doubt that the power of the lobbyist consists in great part, if not altogether, in the facility afforded him by the Committee system (Wilson 2006, 132).

By the time Wilson finished Congressional Government, Grover Cleveland's presidency had restored Wilson's faith in the American system. Vigorous presidencies like those of William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt further convinced Wilson that parliamentary government wasn't necessary to achieve reform. In 1908, in his last scholarly work, Constitutional Government of the United States, Wilson wrote that the presidency "will be as big as and as influential as the man who occupies it." He thought that presidents could be party leaders in the same way prime ministers were. In a bit of prescient analysis, Wilson wrote that the parties could be reorganized along ideological, not geographic, lines. "Eight words," Wilson wrote, "contain the sum of the present degradation of our political parties: No leaders, no principles; no principles, no parties" (Lazare 1996, 145).

Academic Career

Wilson served on the faculties of Bryn Mawr College and Wesleyan University (where he also coached the football team), before joining the Princeton faculty as professor of jurisprudence and political economy in 1890. While there, he was one of the faculty members of the short-lived coordinate college, Evelyn College for Women.

Princeton's trustees promoted Professor Wilson to president of the university in 1902. He had bold plans for his new role. Although the school's endowment was barely $4 million, he sought $2 million for a preceptorial system of teaching, $1 million for a school of science, and nearly $3 million for new buildings and salary raises. As a long-term objective, Wilson sought $3 million for a graduate school and $2.5 million for schools of jurisprudence and electrical engineering, as well as a museum of natural history. He achieved little of that because he was not a strong fund raiser, but he did grow the faculty from 112 to 174 men, most of them personally selected as outstanding teachers. The curriculum guidelines he developed proved important progressive innovations in the field of higher education. To enhance the role of expertise, Wilson instituted academic departments and a system of core requirements where students met in groups of six with preceptors, followed by two years of concentration in a selected major. He tried to raise admission standards and to replace the "gentleman C" with serious study. Wilson aspired, as he told alumni, "to transform thoughtless boys performing tasks into thinking men."

From 1906 to 1910, he attempted to curtail the influence of the elitist "social clubs" by moving the students into colleges, a move that was met with resistance from many alumni. Wilson felt that to compromise "would be to temporize with evil" (Walworth 1958, 109). Even more damaging was his confrontation with Andrew Fleming West, dean of the graduate school, and West's ally, former President Grover Cleveland, a trustee. Wilson wanted to integrate the proposed graduate building into the same quadrangle with the undergraduate colleges; West wanted them separated. West outmaneuvered Wilson, and the trustees rejected Wilson's plan for colleges in 1908, then endorsing West's plans in 1909. The national press covered the confrontation as a battle of the elites (West) versus democracy (Wilson). Wilson, after considering resignation, decided to take up invitations to move into New Jersey state politics (Walworth 1958, ch. 6â8). In 1911, Wilson was elected governor of New Jersey, and served in this office until becoming president in 1913.

Presidency

Economic Policy

Woodrow Wilson's first term was especially significant for its economic reforms. His "New Freedom" pledges of antitrust modification, tariff revision, and reform in banking and currency matters transformed the U.S. economy. Those policies continued the push for a modern economy, an economy that exists to this day.

Federal Reserve

Many historians agree that, "the Federal Reserve Act was the most important legislation of the Wilson era and one of the most important pieces of legislation in the history of the United States" (Link 2002, 370). Wilson had to outwit bankers and enemies of banks, North and South, Democrats and Republicans, to secure passage of the Federal Reserve System in late 1913 (Link 1956, 199â240). He took a bankers' plan that had been designed by conservative Republicansâled by Nelson A. Aldrich and banker Paul M. Warburgâand passed it. Wilson had to outmaneuver the powerful agrarian wing of the party, led by William Jennings Bryan, which strenuously denounced banks and Wall Street. The agrarian-minded opposition wanted a government-owned central bank that could print paper money whenever Congress wanted; Wilson convinced them that because Federal Reserve notes were obligations of the government, the plan fit their demands.

Southerners and westerners learned from Wilson that the system was decentralized into 12 districts and worried that it would weaken New York and strengthen the hinterlands. One key opponent, Congressman Carter Glass, was given credit for the bill, and his home of Richmond, Virginia, was made a district headquarters. Powerful Senator James Reed of Missouri was given two district headquarters in St. Louis and Kansas City. Wilson called for Warburg and other prominent bankers to direct the new system. As it turned out, the New York branch ended up dominating the Fed, thus keeping power on Wall Street. The new system began operations in 1915 and played a major role in financing the Allied and American war efforts in World War I.

Other Economic Policies

The Underwood Tariff lowered the levy charged on imported goods and included a new, graduated income tax. The revenue thereby lost was replaced by that tax, which was authorized by the 16th Amendment to the Constitution. Another reform, the Seaman's Act of 1915, improved working conditions for merchant sailors. As response to the Titanic disaster, it required all ships to be retrofitted with lifeboats. An unfortunate side effect of this was a dramatic increase in the sailing weight of vessels. The cruise ship Eastland sank in Chicago as a result, killing over 800 tourists.

Wilson's economic reforms weren't only targeted at Wall Street; he also pushed for legislation to help farmers. The Smith Lever Act of 1914 created the modern system of agricultural extension agents sponsored by the state agricultural colleges. The agents there taught new techniques to farmers in a hope to increase agricultural productivity. And, beginning in 1916, the Federal Farm Loan Board issued low-cost, long-term mortgages to farmers.

The Keating-Owen Act of 1916 attempted to curtail child labor, but the U.S. Supreme Court declared it unconstitutional in 1918.

In the summer of 1916, Wilson's economic policy was tested when the railroad brotherhoods threatened to shut down the national transportation system. The president tried to bring labor and management together, but management refused to work on a compromise. Wilson then pushed Congress to pass the Adamson Act in September 1916, to prevent the strike. The act imposed an 8-hour workday in the industry at the same pay rate as before. As a result of the act, many more unions threw their support behind Wilson for his reelection. Railroad companies challenged the act, eventually appealing it to the Supreme Court; the Court found it constitutional.

Antitrust

Wilson broke with the "big-lawsuit" tradition of his predecessors Taft and Roosevelt as "Trustbusters" by finding a new approach to encouraging competition through the Federal Trade Commission, which focused on stopping "unfair" trade practices. In addition, Wilson pushed through Congress the Clayton Antitrust Act. It made certain business practices illegal, such as price discrimination, agreements forbidding retailers from handling other companiesâ products, and directorates and agreements to control other companies. This piece of legislation was more powerful than previous anti-trust laws because individual officers of corporations could be held responsible if their companies broke the law. It wasn't, however, entirely negative for business. The new legislation set out clear guidelines that corporations could follow, which made for a dramatic improvement over the previously uncertain business climate. Samuel Gompers considered the Clayton Antitrust Act the "Magna Carta" of labor because it ended the era of union liability antitrust laws.

1916 Reelection

Wilson was able to win reelection in 1916 by picking up many votes that had gone to Theodore Roosevelt or Eugene Debs in 1912. His supporters praised him for avoiding war with Germany or Mexico while maintaining a firm national policy. Those supporters noted that "He kept us out of the war." Wilson, however, never promised to keep out of war regardless of provocation. In his second inaugural address, Wilson alluded to the possibility of future American involvement in the conflict:

"We have been obliged to arm ourselves to make good our claim to a certain minimum of right of freedom of action. We stand firm in armed neutrality since it seems that in no other way we can demonstrate what it is we insist upon and cannot forget. We may even be drawn on, by circumstances, not by our own purpose or desire, to a more active assertion of our rights as we see them and a more immediate association with the great struggle itself" (McPherson 2004, 410).

World War I

Wilson spent 1914 through the beginning of 1917 trying to keep the United States out of World War I, which was enveloping Europe at the time. Playing the role of mediator, Wilson offered to broker a settlement between the belligerents, but neither the Allies nor the Central Powers took him seriously. At home, Wilson had to deal with Republicans, led by Theodore Roosevelt, who strongly criticized his pro-peace stance and refusal to build up the U.S. Army in anticipation of the threat of war.

The United States retained its official neutrality until 1917. Germany's unrestricted submarine warfare provided the political support for U.S. entry into the war on the side of the Allies.

Wartime American, 1917

When Germany resumed unrestricted submarine warfare in early 1917 and made a clumsy attempt to get Mexico as an ally via the Zimmermann Telegram, Wilson called for congressional support to take America into the Great War as a âwar to end all wars." He did not sign any alliance with Great Britain or France but operated as an independent force. Wilson raised a massive army through conscription and gave command to General John J. Pershing, allowing Pershing a free hand as to tactics, strategy, and even diplomacy.

Wilson had decided by then that the war had become a real threat to humanity. Unless the U.S. threw its weight into the war, as he stated in his declaration of war speech, Western civilization itself could be destroyed. His statement announcing a "war to end all wars" meant that he wanted to build a basis for peace that would prevent future catastrophic wars and needless death and destruction. This provided the basis of Wilson's post-war Fourteen Points, which were intended to resolve territorial disputes, ensure free trade and commerce, and establish a peacemaking organization, which later emerged as the League of Nations.

To stop defeatism at home, Wilson pushed Congress to pass the Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918 to suppress anti-British, pro-German, or anti-war opinions. He welcomed socialists who supported the war, like Walter Lippmann, but would not tolerate those who tried to impede the war effortsâmany of whom ended up in prison. His wartime policies were strongly pro-labor, and the American Federation of Labor and other unions saw enormous growth in membership and wages. There was no rationing, so consumer prices soared. As income taxes increased, white-collar workers suffered. Appeals to buy war bonds were highly successful, however. Bonds had the result of shifting the cost of the war to the affluent 1920s.

Wilson set up the United States Committee on Public Information, headed by George Creel (thus its popular name, Creel Commission), which filled the country with patriotic anti-German appeals and conducted various forms of censorship.

Other Foreign Affairs

Between 1914 and 1918, the United States intervened in Latin America, particularly in Mexico, Haiti, Cuba, and Panama. The U.S. maintained troops in Nicaragua throughout his administration and used them to select the president of Nicaragua and then to force Nicaragua to pass the Bryan-Chamorro Treaty. American troops in Haiti forced the Haitian legislature to choose the candidate Wilson selected as Haitian president. American troops occupied Haiti between 1915 and 1934.

After Russia left World War I following its Bolshevik Revolution and started providing help to the Germans, the Allies sent troops to prevent a German takeover. Wilson used expeditionary forces to hold key cities and rail lines in Russia, though they did not engage in combat. He withdrew the soldiers on April 1, 1920 (Levin 1968, 67; Dirksen 1969).

Versailles 1919

After the Great War, Wilson participated in negotiations with the aim of assuring statehood for formerly oppressed nations and an equitable peace. On January 8, 1918, Wilson made his famous Fourteen Points address, introducing the idea of a League of Nations, an organization with a stated goal of helping to preserve territorial integrity and political independence among large and small nations alike.

Wilson intended the Fourteen Points as a means toward ending the war and achieving an equitable peace for all the nations, including Germany. France and Great Britain, however, had been battered and bloodied and wanted Germany to pay both financially and territorially. British Prime Minister Lloyd George and especially French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau pushed for expensive reparation payments, loss of territory, and harsh limits on Germany's future military strength. Those provisions were eventually included in the final series of treaties under a "war guilt" clause that placed blame for starting the war squarely on Germany.

Unlike the other Allied leaders, Wilson didn't want to harshly punish Germany. He was, however, a pragmatist, and he thought it best to compromise with George and Clemenceau in order to gain their support for his Fourteen Points. Wilson spent six months at Versailles for the 1919 Paris Peace Conference, making him the first U.S. president to travel to Europe while in office. He worked tirelessly to promote his plan, eventually traveling across the United States to bring it directly to the American people. The charter of the proposed League of Nations was incorporated into the conference's Treaty of Versailles.

For his peacemaking efforts, Wilson was awarded the 1919 Nobel Peace Prize. He failed to win Senate support for ratification, however, and the United States never joined the League. Republicans under Henry Cabot Lodge controlled the Senate after the 1918 elections, but Wilson refused to give them a voice at Paris and refused to agree to Lodge's proposed changes. The key point of disagreement was whether the League would diminish the power of Congress to declare war. Historians generally have come to regard Wilson's failure to win U.S. entry into the League as perhaps the biggest mistake of his administration, and even as one of the largest failures of any American presidency ("U.S. historians" 2006).

Post-war: 1919â1920

After the war, in 1919, major strikes and race riots broke out. In the Red Scare, his attorney general ordered the Palmer Raids to deport foreign-born agitators and jail domestic ones. In 1918, Wilson had the socialist leader Eugene V. Debs arrested for trying to discourage enlistment in the army. His conviction was upheld by the Supreme Court.

Wilson broke with many of his closest political friends and allies in 1918â1920. He desired a third term, but his Democratic Party was in turmoil, with German voters outraged at their wartime harassment, and Irish voters angry at his failure to support Irish independence.

Incapacity

On October 2, 1919, Wilson suffered a serious stroke that almost totally incapacitated him; he could barely move his body. The extent of his disability was kept from the public until after his death. Wilson was purposely, with few exceptions, kept out of the presence of Vice President Thomas R. Marshall, his cabinet, and congressional visitors to the White House for the remainder of his presidential term. Meanwhile, his second wife, Edith Wilson, served as steward, selecting issues for his attention and delegating other issues to his cabinet heads. This was, as of 2006, the most serious case of presidential disability in American history and was later cited as a key example to why ratification of the 25th Amendment was seen as important.

Later Life

In 1921, Wilson and his wife retired from the White House to a home in the Embassy Row section of Washington, D.C. Wilson continued going for daily drives and attended Keith's Vaudeville Theater on Saturday nights. Wilson died while on a visit there on February 3, 1924. He was buried in the Washington National Cathedral. Mrs. Wilson stayed in their home for another 37 years, dying on December 28, 1961.

Personal Life

Marriages

In 1885, Woodrow Wilson married Ellen Louise Axson, a woman whose father, like Wilson's, was a Presbyterian minister. She gave birth to three childrenâMargaret, Jessie, and Eleanorâand served as hostess of social functions during Wilson's tenure at Princeton. A gifted painter, Ellen used art to escape from the stress of her social responsibilities. Midway through Wilson's first term, however, Ellen's health failed, and Bright's disease claimed her life in 1914.

Wilson was distraught over the loss of his wife, but, being a relatively young man at the time of her death, American societal views prescribed that he would marry again. In 1915, he met the widow Edith Galt and proposed marriage after a quick courtship. When Wilson suffered his stroke in 1919, Edith nursed him back to health while attending to the daily workings of government.

Racial Views

Historians generally regard Woodrow Wilson as having been a white supremacist, though that was not uncommon for a man of his time and southern upbringing. He, like many white males of his time and before, thought whites to be superior to blacks and other races.

While at Princeton, Wilson turned away black applicants for admission, saying that their desire for education was "unwarranted" (Freund 2002). Later, as President of the United States, Wilson reintroduced official segregation in federal government offices for the first time since 1863. "His administration imposed full racial segregation in Washington and hounded from office considerable numbers of black federal employees" (Foner 1999). Wilson fired many black Republican office holders, but also appointed a few black Democrats. W.E.B. DuBois, a leader of the NAACP, campaigned for Wilson and in 1918 was offered an Army commission in charge of dealing with race relations. DuBois accepted but failed his Army physical and did not serve (Ellis 1992). When a delegation of blacks protested his discriminatory actions, Wilson told them that "segregation is not a humiliation but a benefit, and ought to be so regarded by you gentlemen." In 1914, he told the New York Times that "If the colored people made a mistake in voting for me, they ought to correct it."

Wilson wrote harshly of immigrants in his history books. After he entered politics in 1910, however, Wilson worked to integrate new immigrants into the Democratic Party, into the Army, and into American life. For example, the war bond campaigns were set up so that ethnic groups could boast how much money they gave. He demanded in return during the war that they repudiate any loyalty to the enemy.

Irish Americans were powerful in the Democratic Party and opposed going to war alongside British "enemies," especially after the violent suppression of the Easter Rebellion of 1916. Wilson won them over in 1917 by promising to ask Britain to give Ireland its independence. At Versailles, however, he reneged on that promise, and the Irish-American community vehemently denounced him. Wilson, in turn, blamed the Irish Americans and German Americans for the lack of popular support for the League of Nations, saying, "There is an organized propaganda against the League of Nations and against the treaty proceeding from exactly the same sources that the organized propaganda proceeded from which threatened this country here and there with disloyalty, and I want to sayâI cannot say too oftenâany man who carries a hyphen about with him carries a dagger that he is ready to plunge into the vitals of this Republic whenever he gets ready" (Andrews and Zarefsky 1989; Duff 1968, 1970).

Legacy

Woodrow Wilson's presidency still resonates today, particularly in two specific aspects of American policy. First, many of the economic reforms and policy changes, such as the institution of the Federal Reserve and the income tax, have persisted to the current era. Second, President George W. Bush's foreign policy of democratization and self-determination in the Middle East and Asia leaned heavily on Wilson's Fourteen Points.

Significant Legislation

- Revenue Act of 1913

- Federal Reserve Act of 1913

- Federal Farm Loan Act of 1916

- Espionage Act of 1917

- Sedition Act of 1918

Supreme Court Appointments

Wilson appointed the following Justices to the Supreme Court of the United States:

- James Clark McReynolds' â 1914

- Louis Dembitz Brandeis â 1916

- John Hessin Clarke â 1916

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Andrews, James, and David Zarefsky (eds.). 1989. American Voices, Significant Speeches in American History: 1640â1945. White Plains, NY: Longman. ISBN 978-0801302176

- Bailey, Thomas A. 1947. Wilson and the Peacemakers: Combining Woodrow Wilson and the Lost Peace and Woodrow Wilson and the Great Betrayal. New York, NY: Macmillan.

- Brands, H. W. 2003. Woodrow Wilson: 1913â1921. New York, NY: Times Books. ISBN 0805069550

- Clements, Kendrick A. 1992. The Presidency of Woodrow Wilson. Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas Press. ISBN 070060524X

- Clements, Kendrick A. 1999. Woodrow Wilson: World Statesman. Chicago: I. R. Dee. ISBN 1566632676

- Clements, Kendrick A. 2004. "Woodrow Wilson and World War I." Presidential Studies Quarterly 34(1): 62.

- Dirksen, Everett M. 1969. "Use of U.S. Armed Forces in Foreign Countries." Congressional Record, June 23, 1969, 16840â43.

- Duff, John B. 1968. âThe Versailles Treaty and the Irish-Americans.â Journal of American History 55(3): 582â598.

- Duff, John B. 1970. âGerman-Americans and the Peace, 1918â1920.â American Jewish Historical Quarterly 59(4): 424â459.

- Ellis, Mark. 1992. "'Closing Ranks' and 'Seeking Honors': W.E.B. DuBois in World War I." Journal of American History 79(1): 96â124.

- Foner, Eric. 1999. âExpert Report of Eric Foner.â University of Michigan. Retrieved June 29, 2012.

- Freund, Charles Paul. 2002. âDixiecrats Triumphant: The menacing Mr. Wilson.â Reason Online. Retrieved June 29, 2012.

- Greene, Theodore P., ed. 1957. Wilson at Versailles. Lexington, MA: Heath. ISBN 0669839159

- Hofstadter, Richard. 1948. "Woodrow Wilson: The Conservative as Liberal." In The American Political Tradition, ch. 10.

- Knock, Thomas J. 1995. To End All Wars: Woodrow Wilson and the Quest for a New World Order. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691001502

- Lazare, Daniel. 1996. The Frozen Republic: How the Constitution is Paralyzing Democracy. Harcourt Brace & Company. ISBN 978-0156004947

- Levin, Gordon N., Jr. 1968. Woodrow Wilson and World Politics: America's Response to War and Revolution. London and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-1299117181

- Link, Arthur S. 1947. Wilson: The Road to the White House. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1597402804

- Link, Arthur S. 1956. Wilson: The New Freedom. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1597402811

- Link, Arthur S. 1957. Wilson the Diplomatist: A Look at His Major Foreign Policies. Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press. ASIN B001E34PHQ

- Link, Arthur S. 1960. Wilson: The Struggle for Neutrality: 1914â1915. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ASIN B001E34PHQ

- Link, Arthur S. 1964. Wilson: Confusions and Crises: 1915â1916. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691045757

- Link, Arthur S. 1965. Wilson: Campaigns for Progressivism and Peace: 1916â1917 Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1597402835

- Link, Arthur S., ed. 1982. Woodrow Wilson and a Revolutionary World, 1913â1921. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0807897119

- Link, Arthur S. 1982. Woodrow Wilson and the Progressive Era, 1910â1917. Norwalk, CT: Easton Press. ASIN B000MXIG7E

- Link, Arthur S. 2002. "Woodrow Wilson." In The Presidents: A Reference History, ed. Henry F. Graff, pp. 365â388. New York: Charles Scribnerâs Sons; Thomson/Gale. ISBN 0684312263

- Livermore, Seward W. 1966. Politics is Adjourned: Woodrow Wilson and the War Congress, 1916â1918. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press. ASIN B000J1RYG8

- May, Ernest R. 1959. The World War and American Isolation, 1914â1917. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ASIN B0024TZKOG

- McPherson, James. 2004. To the Best of My Ability. New York: DK Publishing. ISBN 0756607779

- Saunders, Robert M. 1998. In Search of Woodrow Wilson: Beliefs and Behavior. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 031330520X

- Tumulty, Joseph P. 1921. Woodrow Wilson as I Know Him. Retrieved June 29, 2012.

- âU.S. historians pick top 10 presidential errors.â Associated Press. February 18, 2006. Retrieved June 29, 2012.

- Walworth, Arthur. 1958. Woodrow Wilson, vol. 1. New York: Longman's Green.

- Walworth, Arthur. 1986. Wilson and His Peacemakers: American Diplomacy at the Paris Peace Conference, 1919. New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 0393018679

Primary Sources

- Wilson, Woodrow. 1913. The New Freedom. New York: Doubleday. Retrieved June 29, 2012.

- Wilson, Woodrow. 1917. Why We Are at War. New York and London: Harper and Brothers Publishers. Retrieved June 29, 2012.

- Wilson, Woodrow. 1956. The Politics of Woodrow Wilson. Edited by August Heckscher. New York: Harper.

- Wilson, Woodrow. 1966â1994. The Papers of Woodrow Wilson, 69 vol., edited by Arthur S. Link. Retrieved June 29, 2012.

- Wilson, Woodrow. 2001. Congressional Government in the United States. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 0765808668

- Wilson, Woodrow. 2002. The New Democracy: Presidential Messages, Addresses and Other Papers (1913â1917). University Press of the Pacific. ISBN 0898757754

- Wilson, Woodrow. 2002. War and Peace: Presidential Messages, Addresses and Public Paper (1917â1924). University Press of the Pacific. ISBN 0898758157

- Wilson, Woodrow. 2006. Congressional Government: A Study in American Politics. Dover Publications. ISBN 0486447359

External links

All links retrieved May 17, 2023.

- First Inaugural Address

- Second Inaugural Address

- Woodrow Wilson Presidential Library at His Birthplace â Staunton, Virginia

- Boyhood Home of President Woodrow Wilson â Augusta, Georgia

- Woodrow Wilson House â Washington, D.C.

- Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars â Washington, D.C.

- Library of Congress: "Today in History: December 28"

- Library of Congress: "Today in History: June 9"

- Woodrow Wilson Ancestral Home

| ||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.