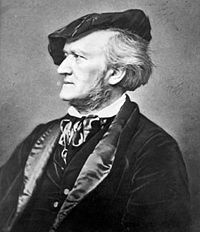

Richard Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner (May 22, 1813 â February 13, 1883) was an influential German composer, conductor, music theorist, and essayist, primarily known for his operas (or "music dramas" as he later came to call them). His compositions, particularly those of his later period, are notable for their contrapuntal texture, rich chromaticism, harmonies and orchestration, and elaborate use of leitmotifs: themes associated with specific characters, locales, or plot elements. Wagner's chromatic musical language prefigured later developments in European classical music, including extreme chromaticism and atonality. He transformed musical thought through his idea of Gesamtkunstwerk ("total artwork"), epitomized by his monumental four-opera cycle Der Ring des Nibelungen (1876). His concept of leitmotif and integrated musical expression was also a strong influence on many twentieth century film scores. Wagner was and remains a controversial figure, both for his musical and dramatic innovations, and for his anti-semitic and political opinions.

Biography

Early life

Richard Wagner was born in Leipzig, Germany, on May 22, 1813. His father, Friedrich Wagner, who was a minor municipal official, died six months after Richard's birth. In August 1814 his mother, Johanne PĂ€tz, married the actor Ludwig Geyer, and moved with her family to his residence in Dresden. Geyer, who, it has been claimed, may have been the boy's actual father, died when Richard was eight. Wagner was largely brought up by a single mother.

At the end of 1822, at the age of nine, he was enrolled in the Kreuzschule, Dresden, (under the name Wilhelm Richard Geyer), where he received some small amount of piano instruction from his Latin teacher, but could not manage a proper scale and mostly preferred playing theater overtures by ear.

Young Richard Wagner entertained ambitions to be a playwright, and first became interested in music as a means of enhancing the dramas that he wanted to write and stage. He soon turned toward studying music, for which he enrolled at the University of Leipzig in 1831. Among his earliest musical enthusiasms was Ludwig van Beethoven.

First Opera

In 1833, at the age of 20, Wagner composed his first complete opera, Die Feen. This opera, which clearly imitated the style of Carl Maria von Weber, would go unproduced until half a century later, when it was premiered in Munich shortly after the composer's death in 1883.

Meanwhile, Wagner held brief appointments as musical director at opera houses in Magdeburg and Königsberg, during which he wrote Das Liebesverbot, based on William Shakespeare's Measure for Measure. This second opera was staged at Magdeburg in 1836, but closed before the second performance, leaving the composer (not for the last time) in serious financial difficulties.

Marriage

On November 24, 1836, Wagner married actress Christine Wilhelmine "Minna" Planer. They moved to the city of Riga, then in the Russian Empire, where Wagner became music director of the local opera. A few weeks afterward, Minna ran off with an army officer who then abandoned her, penniless. Wagner took Minna back, but this was but the first debĂącle of a troubled marriage that would end in misery three decades later.

By 1839, the couple had amassed such large debts that they fled Riga to escape from creditors (debt would plague Wagner for most of his life). During their flight, they and their Newfoundland dog, Robber, took a stormy sea passage to London, from which Wagner drew the inspiration for Der Fliegende HollÀnder (The Flying Dutchman). The Wagners spent 1840 and 1841 in Paris, where Richard made a scant living writing articles and arranging operas by other composers, largely on behalf of the Schlesinger publishing house. He also completed Rienzi and Der Fliegende HollÀnder during this time.

Dresden

Wagner completed writing his third opera, Rienzi, in 1840. Largely through the agency of Meyerbeer, it was accepted for performance by the Dresden Court Theatre (Hofoper) in the German state of Saxony. Thus in 1842, the couple moved to Dresden, where Rienzi was staged to considerable success. Wagner lived in Dresden for the next six years, eventually being appointed the Royal Saxon Court Conductor. During this period, he wrote and staged Der fliegende HollÀnder and TannhÀuser, the first two of his three middle-period operas.

The Wagners' stay at Dresden was brought to an end by Richard's involvement in left-wing politics. A nationalist movement was gaining force in the independent German States, calling for constitutional freedoms and the unification of the weak princely states into a single nation. Richard Wagner played an enthusiastic role in this movement, receiving guests at his house that included his colleague August Röckel, who was editing the radical left-wing paper VolksblÀtter, and the Russian anarchist Mikhail Bakunin.

Widespread discontent against the Saxon government came to a boil in April 1849, when King Frederick Augustus II of Saxony dissolved Parliament and rejected a new constitution pressed upon him by the people. The May Uprising broke out, in which Wagner played a minor supporting role. The incipient revolution was quickly crushed by an allied force of Saxon and Prussian troops, and warrants were issued for the arrest of the revolutionaries. Wagner had to flee, first to Paris and then to ZĂŒrich. Röckel and Bakunin failed to escape and were forced to endure long terms of imprisonment.

Exile

Wagner spent the next 12 years in exile. He had completed Lohengrin before the Dresden uprising, and now wrote desperately to his friend Franz Liszt to have it staged in his absence. Liszt, who proved to be a friend in need, eventually conducted the premiere in Weimar in August 1850.

Nevertheless, Wagner found himself in grim personal straits, isolated from the German musical world and without any income to speak of. The musical sketches he was penning, which would grow into the mammoth work Der Ring des Nibelungen, seemed to have no prospects of seeing performance. His wife Minna, who had disliked the operas he had written after Rienzi, was falling into a deepening depression. Finally, he fell victim to a serious skin infection erysipelas which made it difficult for him to continue writing.

Wagner's primary output during his first years in ZĂŒrich was a set of notable essays: "The Art-Work of the Future" (1849), in which he described a vision of opera as Gesamtkunstwerk, or "total artwork," in which the various arts such as music, song, dance, poetry, visual arts, and stagecraft were unified; "Jewry in Music" (1850), a tract directed against Jewish composers; and "Opera and Drama" (1851), which described ideas in aesthetics that he was putting to use on the Ring operas.

Schopenhauer

In the following years, Wagner came upon two independent sources of inspiration, leading to the creation of his celebrated Tristan und Isolde. The first came to him in 1854, when his poet friend Georg Herwegh introduced him to the works of the philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer. Wagner would later call this the most important event of his life. His personal circumstances certainly made him an easy convert to what he understood to be Schopenhauer's philosophy - a deeply pessimistic view of the human condition. He would remain an adherent of Schopenhauer for the rest of his life, even after his fortunes improved.

One of Schopenhauer's doctrines was that music held a supreme role amongst the arts, since it was the only one unconcerned with the material world. Wagner quickly embraced this claim, which must have resonated strongly despite its direct contradiction with his own arguments, in "Opera and Drama," that music in opera had to be subservient to the cause of drama. Wagner scholars have since argued that this Schopenhauerian influence caused Wagner to assign a more commanding role to music in his later operas, including the latter half of the Ring cycle which he had yet to compose. Many aspects of Schopenhauerian doctrine undoubtedly found its way into Wagner's subsequent libretti. For example, the self-renouncing cobbler-poet Hans Sachs in Die Meistersinger, generally considered Wagner's most sympathetic character, is a quintessentially Schopenhauerian creation (despite being based on a real person).

Mrs. Wesendonck

Wagner's second source of inspiration was the poet-writer Mathilde Wesendonck, the wife of the silk merchant Otto von Wesendonck. Wagner met the Wesendoncks in ZĂŒrich in 1852. Otto, a fan of Wagner's music, placed a cottage on his estate at Wagner's disposal. By 1857, Wagner had become infatuated with Mathilde. Though Mathilde seems to have returned some of his affections, she had no intention of jeopardizing her marriage, and kept her husband informed of her contacts with Wagner. Nevertheless, the affair inspired Wagner to put aside his work on the Ring cycle (which would not be resumed for the next 12 years) and begin work on Tristan und Isolde, based on the Arthurian love story of the knight Tristan and the (already-married) Lady Isolde.

The uneasy affair collapsed in 1858, when his wife intercepted a letter from Wagner to Mathilde. After the resulting confrontation, Wagner left ZĂŒrich alone, bound for Venice. The following year, he once again moved to Paris to oversee production of a new revision of TannhĂ€user, staged thanks to efforts of Princess de Metternich. The premiere of the new TannhĂ€user in 1861 was an utter fiasco, due to disturbances caused by aristocrats from the Jockey Club. Further performances were cancelled, and Wagner hurriedly left the city.

In 1861, the political ban against Wagner was lifted, and the composer settled in Biebrich, Prussia, where he began work on Die Meistersinger von NĂŒrnberg. Remarkably, this opera is by far his sunniest work. (His second wife Cosima would later write: "when future generations seek refreshment in this unique work, may they spare a thought for the tears from which the smiles arose.") In 1862, Wagner finally parted with Minna, though he (or at least his creditors) continued to support her financially until her death in 1866.

Patronage of King Ludwig II

Wagner's fortunes took a dramatic upturn in 1864, when King Ludwig II assumed the throne of Bavaria at the age of 18. The young King, an ardent admirer of Wagner's operas since childhood, had the composer brought to Munich. He settled Wagner's considerable debts, and made plans to have his new opera produced. After grave difficulties in rehearsal, Tristan und Isolde premiered to enormous success at the National Theatre in Munich on June 10, 1865.

In the meantime, Wagner became embroiled in another affair, this time with Cosima von BĂŒlow, the wife of the conductor Hans von BĂŒlow, one of Wagner's most ardent supporters and the conductor of the Tristan premiere. Cosima was the illegitimate daughter of Franz Liszt and the famous Countess Marie d'Agoult, and 24 years younger than Wagner. Liszt disapproved of his daughter seeing Wagner, though the two men were friends. In April 1865, she gave birth to Wagner's illegitimate daughter, who was named Isolde. Their indiscreet affair scandalized Munich, and to make matters worse, Wagner fell into disfavor amongst members of the court, who were suspicious of his influence on the King. In December 1865, Ludwig was finally forced to ask the composer to leave Munich. He apparently also toyed with the idea of abdicating in order to follow his hero into exile, but Wagner quickly dissuaded him.

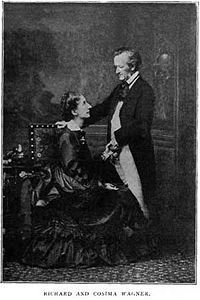

Ludwig installed Wagner at the villa Tribschen, beside Switzerland's Lake Lucerne. Die Meistersinger was completed at Tribschen in 1867, and premiered in Munich on June 21 the following year. In October, Cosima finally convinced Hans von BĂŒlow to grant her a divorce. Richard and Cosima were married on August 25, 1870. (Liszt would not speak to his new son-in-law for years to come.) On Christmas Day of that year, Wagner presented the Siegfried Idyll for Cosima's birthday. The marriage to Cosima lasted to the end of Wagner's life. They had another daughter, named Eva, and a son named Siegfried.

It was at Tribschen, in 1869, that Wagner first met the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche. Wagner's ideas were a major influence on Nietzsche, who was 31 years his junior. Nietzsche's first book, Die Geburt der Tragödie ("The Birth of Tragedy," 1872), was dedicated to Wagner. The relationship eventually soured, as Nietzsche became increasingly disillusioned with various aspects of Wagner's thought, especially his appropriation of Christianity in Parsifal and his anti-Semitism, and with the blind devotion of Wagner's followers. In Der Fall Wagner ("The Case of Wagner," 1888) and Nietzsche Contra Wagner ("Nietzsche vs. Wagner," 1889), he obsessively criticized Wagner's music while conceding its power, and condemned Wagner as decadent and corrupt, even criticizing his earlier adulatory views of the composer.

Bayreuth

Wagner, settled into his newfound domesticity, turned his energies toward completing the Ring cycle. At Ludwig's insistence, "special previews" of the first two works of the cycle, Das Rheingold and Die WalkĂŒre, were performed at Munich, but Wagner wanted the complete cycle to be performed in a new, specially-designed opera house.

In 1871, he decided on the small town of Bayreuth as the location of his new opera house. The Wagners moved there the following year, and the foundation stone for the Bayreuth Festspielhaus ("Festival House") was laid. In order to raise funds for the construction, "Wagner societies" were formed in several cities, and Wagner himself began touring Germany conducting concerts. However, sufficient funds were only raised after King Ludwig stepped in with another large grant in 1874. Later that year, the Wagners moved into their permanent home at Bayreuth, a villa that Richard dubbed Wahnfried ("Peace/freedom from delusion/madness," in German).

The Festspielhaus finally opened in August 1876 with the premiere of the Ring cycle and has continued to be the site of the Bayreuth Festival ever since.

Final years

In 1877, Wagner began work on Parsifal, his final opera. The composition took four years, during which he also wrote a series of increasingly reactionary essays on religion and art.

Wagner completed Parsifal in January 1882, and a second Bayreuth Festival was held for the new opera. Wagner was by this time extremely ill, having suffered through a series of increasingly severe angina attacks. During the sixteenth and final performance of Parsifal on August 29, he secretly entered the pit during Act III, took the baton from conductor Hermann Levi, and led the performance to its conclusion.

After the Festival, the Wagner family journeyed to Venice for the winter. On February 13, 1883, Richard Wagner died of a heart attack in the Palazzo Vendramin on the Grand Canal. His body was returned to Bayreuth and buried in the garden of the Villa Wahnfried.

Franz Liszt's memorable piece for pianoforte solo, La lugubre gondola, evokes the passing of a black-shrouded funerary gondola bearing Richard Wagner's mortal remains over the Grand Canal.

Works

Opera

Wagner's music dramas are his primary artistic legacy. These can be divided chronologically into three periods.

Wagner's early stage began at age 19 with his first attempt at an opera, Die Hochzeit (The Wedding), which Wagner abandoned at an early stage of composition in 1832. Wagner's three completed early-stage operas are Die Feen(The Fairies), Das Liebesverbot (The Ban on Love), and Rienzi. Their compositional style was conventional, and did not exhibit the innovations that marked Wagner's place in musical history. Later in life, Wagner said that he did not consider these immature works to be part of his oeuvre; he was irritated by the ongoing popularity of Rienzi during his lifetime. These works are seldom performed, though the overture to Rienzi has become a concert piece.

Wagner's middle stage output is considered to be of remarkably higher quality, and begins to show the deepening of his powers as a dramatist and composer. This period began with Der fliegende HollÀnder (The Flying Dutchman), followed by TannhÀuser and Lohengrin. These works are widely performed today.

Wagner's late stage operas are his masterpieces that advanced the art of opera. Some are of the opinion that Tristan und Isolde (Tristan and Iseult) is Wagner's greatest single opera. Die Meistersinger von NĂŒrnberg (The Mastersingers of Nuremberg) is Wagner's only comedy (apart from his early and forgotten Das Liebesverbot) and one of the lengthiest operas still performed. Der Ring des Nibelungen, commonly referred to as the Ring cycle, is a set of four operas based loosely on figures and elements of Teutonic myth, particularly from later period Norse mythology. Wagner drew largely from Icelandic epics, namely, The Poetic Edda, The Volsunga Saga and the later Austrian Nibelungenlied. Taking around 20 years to complete, and spanning roughly 17 hours in performance, the Ring cycle has been called the most ambitious musical work ever composed. Wagner's final opera, Parsifal, which was written especially for the opening of Wagner's Festspielhaus in Bayreuth and which is described in the score as a "BĂŒhnenweihfestspiel" (festival play for the consecration of the stage), is a contemplative work based on the Christian legend of the Holy Grail.

Through his operas and theoretical essays, Wagner exerted a strong influence on the operatic medium. He was an advocate of a new form of opera which he called "music drama," in which all the musical and dramatic elements were fused together. Unlike other opera composers, who generally left the task of writing the libretto (the text and lyrics) to others, Wagner wrote his own libretti, which he referred to as "poems." Most of his plots were based on Northern European mythology and legend. Further, Wagner developed a compositional style in which the orchestra's role is equal to that of the singers. The orchestra's dramatic role includes its performance of the leitmotifs, musical themes that announce specific characters, locales, and plot elements; their complex interleaving and evolution illuminates the progression of the drama.

Wagner's musical style is often considered the epitome of classical music's Romantic period, due to its unprecedented exploration of emotional expression. He introduced new ideas in harmony and musical form, including extreme chromaticism. In Tristan und Isolde, he explored the limits of the traditional tonal system that gave keys and chords their identity, pointing the way to atonality in the twentieth century. Some music historians date the beginning of modern classical music to the first notes of Tristan, the so-called Tristan chord.

Early stage

- (1832) Die Hochzeit (The Wedding) (abandoned before completion)

- (1833) Die Feen (The Fairies)

- (1836) Das Liebesverbot (The Ban on Love)

- (1837) Rienzi, der Letzte der Tribunen (Rienzi, the Last of the Tribunes)

Middle stage

- (1843) Der fliegende HollÀnder (The Flying Dutchman)

- (1845) TannhÀuser

- (1848) Lohengrin

Late stage

- (1859) Tristan und Isolde

- (1867) Die Meistersinger von NĂŒrnberg (The Mastersingers of Nuremberg)

- Der Ring des Nibelungen (The Ring of the Nibelung), consisting of:

- (1854) Das Rheingold (The Rhinegold)

- (1856) Die WalkĂŒre (The Valkyrie)

- (1871) Siegfried (previously entitled Jung-Siegfried or Young Siegfried, and Der junge Siegfried or The young Siegfried)

- (1874) GötterdÀmmerung (Twilight of the Gods) (originally entitled Siegfrieds Tod or The Death of Siegfried)

- (1882) Parsifal

Non-operatic music

Apart from his operas, Wagner composed relatively few pieces of music. These include a single symphony (written at the age of 19), a Faust symphony (of which he only finished the first movement, which became the Faust Overture), and some overtures, choral and piano pieces, and a re-orchestration of Gluck's Iphigénie en Aulide. Of these, the most commonly performed work is the Siegfried Idyll, a piece for chamber orchestra written for the birthday of his second wife, Cosima. The Idyll draws on several motifs from the Ring cycle, though it is not part of the Ring. The next most popular are the Wesendonck Lieder, properly known as Five Songs for a Female Voice, which were composed for Mathilde Wesendonck while Wagner was working on Tristan. An oddity is the "American Centennial March" of 1876, commissioned by the city of Philadelphia for the opening of the Centennial Exposition, for which Wagner was paid $5,000.

After completing Parsifal, Wagner apparently intended to turn to the writing of symphonies. However, nothing substantial had been written by the time of his death.

The overtures and orchestral passages from Wagner's middle and late-stage operas are commonly played as concert pieces. For most of these, Wagner wrote short passages to conclude the excerpt so that it does not end abruptly. This is true, for example, of the Parsifal prelude and Siegfried's Funeral Music. A curious fact is that the concert version of the Tristan prelude is unpopular and rarely heard; the original ending of the prelude is usually considered to be better, even for a concert performance.

One of the most popular wedding marches played as the bride's processional in English-speaking countries, popularly known as "Here Comes the Bride," takes its melody from the "Bridal Chorus" of Lohengrin. In the opera, it is sung as the bride and groom leave the ceremony and go into the wedding chamber. The calamitous marriage of Lohengrin and Elsa, which reaches irretrievable breakdown 20 minutes after the chorus has been sung, has failed to discourage this widespread use of the piece.

Writings

Wagner was an extremely prolific writer, authoring hundreds of books, poems, and articles, as well as a massive amount of correspondence. His writings covered a wide range of topics, including politics, philosophy, and detailed analyses (often mutually contradictory) of his own operas. Essays of note include "Oper und Drama" ("Opera and Drama," 1851), an essay on the theory of opera, and "Das Judenthum in der Musik" ("Jewry in Music," 1850), a polemic directed against Jewish composers in general, and Giacomo Meyerbeer in particular. He also wrote an autobiography, My Life (1880).

Theatre Design and Operation

Wagner was responsible for several theatrical innovations developed at the Bayreuth Festspielhaus, an opera house specially constructed for the performance of his operas (for the design of which he appropriated many of the ideas of his former colleague, Gottfried Semper, which he had solicited for a proposed new opera house at Munich). These innovations include darkening the auditorium during performances, and placing the orchestra in a pit out of view of the audience. The Bayreuth Festspielhaus is the venue of the annual Richard Wagner Festival, which draws thousands of opera fans to Bayreuth each summer.

The orchestra pit at Bayreuth is interesting for two reasons:

- The first violins are positioned on the right-hand side of the conductor instead of their usual place on the left side. This is in all likeliness because of the way the sound is intended to be directed towards the stage rather than directly on the audience. This way the sound has a more direct line from the first violins to the back of the stage where it can be then reflected to the audience.

- Double basses, 'cellos and harps (when more than one used, e.g. Ring) are split into groups and placed on either side of the pit.

Wagner's influence and legacy

Wagner made highly significant, if controversial, contributions to art and culture. In his lifetime, and for some years after, Wagner inspired fanatical devotion amongst his followers, and was occasionally considered by them to have a near god-like status. His compositions, in particular Tristan und Isolde, broke important new musical ground. For years afterward, many composers felt compelled to align themselves with or against Wagner. Anton Bruckner and Hugo Wolf are indebted to him especially, as are CĂ©sar Franck, Henri Duparc, Ernest Chausson, Jules Massenet, Alexander von Zemlinsky, Hans Pfitzner and dozens of others. Gustav Mahler said, "There was only Beethoven and Wagner." The twentieth century harmonic revolutions of Claude Debussy and Arnold Schoenberg (tonal and atonal modernism, respectively) have often been traced back to Tristan. The Italian form of operatic realism known as verismo owes much to Wagnerian reconstruction of musical form. It was Wagner who first demanded that the lights be dimmed during dramatic performances, and it was his theatre at Bayreuth which first made use of the sunken orchestra pit, which at Bayreuth entirely conceals the orchestra from the audience.

Wagner's theory of musical drama has shaped even completely new art forms, including film scores such as John Williams' music for Star Wars. American producer Phil Spector with his "wall of sound" was strongly influenced by Wagner's music. The rock subgenre of heavy metal music also shows a Wagnerian influence with its strong paganistic stamp. In Germany Rammstein and Joachim Witt (his most famous albums are called Bayreuth for that reason) are both strongly influenced by Wagner's music. The movie "The Ring of the Nibelungs" drew both from historical sources as well as Wagner's work, and set a ratings record when aired as a two-part mini-series on German television. It was subsequently released in other countries under a variety of names, including "Dark Kingdom: The Dragon King" in the USA.

Wagner's influence on literature and philosophy is also significant. Friedrich Nietzsche was part of Wagner's inner circle during the early 1870s, and his first published work The Birth of Tragedy proposed Wagner's music as the Dionysian rebirth of European culture in opposition to Apollonian rationalist decadence. Nietzsche broke with Wagner following the first Bayreuth Festival, believing that Wagner's final phase represented a pandering to Christian pieties and a surrender to the new demagogic German Reich. In the twentieth century, W. H. Auden once called Wagner "perhaps the greatest genius that ever lived," while Thomas Mann and Marcel Proust were heavily influenced by him and discussed Wagner in their novels. He is discussed in some of the works of James Joyce although Joyce was known to detest him. Wagner is one of the main subjects of T. S. Eliot's The Waste Land, which contains lines from Tristan und Isolde and refers to The Ring and Parsifal. Charles Baudelaire, Stéphane Mallarmé and Paul Verlaine worshipped Wagner. Many of the ideas his music brought up, such as the association between love and death (or Eros and Thanatos) in Tristan, predated their investigation by Sigmund Freud.

Not all reaction to Wagner was positive. For a time, German musical life divided into two factions, Wagner's supporters and those of Johannes Brahms; the latter, with the support of the powerful critic Eduard Hanslick, championed traditional forms and led the conservative front against Wagnerian innovations. Even those who, like Debussy, opposed him ("that old poisoner"), could not deny Wagner's influence. Indeed, Debussy was one of many composers, including Tchaikovsky, who felt the need to break with Wagner precisely because his influence was so unmistakable and overwhelming. Others who resisted Wagner's influence included Rossini ("Wagner has wonderful moments, and dreadful quarters of an hour"), though his own "Guillaume Tell," at over four hours, is comparable to Wagner's operas in length.

Religious Philosophy

Though he befriended philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche and the two men shared certain anti-Christian views, especially with regard to puritanical attitudes about sexuality, religious belief was nonetheless a part of Wagner's upbringing. As a boy he once stated that he "yearned to, with ecstatic fervor, to hang upon the Cross in the place of the Saviour." One of his early works, Jesus of Nazareth was conceived after a study of the Gospels and included verses from the New Testament. Another work, The Love Feast of the Twelve Apostles, was also based on Biblical texts.

The incongruities of his life from a moral and ethical perspective remain a source of controversy and are as perplexing today as they were during his life. Yet his acknowledgment of the reality of the redemptive aspects of Christian faith in attaining happiness and fulfillment cannot be denied. He wrote: "When I found this yearning could never be stilled by modern life, in escaping from its claims upon me by self-destruction, I came to the primal fount of every modern rendering of the situationâto the man Jesus of Nazareth."

As late as 1880 he wrote an essay entitled "Religion and Art" in which he once again attests to the redemptive power of the love of Jesus writing that the blood of Jesus "was a fountainhead of pity, which streams through the human species," and that the only hope for attaining a peaceful, ideal world was, "partaking of the blood of Christ."

Wagner's Christianity was unorthodox to be sure (he disdained the Old Testament and the Ten Commandments), yet his perspicacious views of the metaphysical synergy between music, creativity and spirituality are never far from his life experience. When composing his opera Tristan und Isolde, he claimed to have been in an otherworldly state of mind saying, "Here, in perfect trustfulness, I plunged into the inner depths of soul-events and from the innermost center of the world I fearlessly built up to its outer formâŠ. Life and death, the whole meaning and existence of the outer world, here hang on nothing but the inner movements of the soul."

Controversies

- "I sometimes think there are two Wagners in our culture, almost unrecognizably different from one another: the Wagner possessed by those who know his work, and the Wagner imagined by those who know him only by name and reputation." (Bryan Magee. Wagner and Philosophy. 2002)[1]

Wagner's operas, writings, his politics, beliefs and unorthodox lifestyle made him a controversial figure during his lifetime. In September 1876 Karl Marx complained in a letter to his daughter Jenny: "Wherever one goes these days one is pestered with the question: 'what do you think of Wagner?'" Following Wagner's death, the debate about and appropriation of his beliefs, particularly in Germany during the twentieth century, made him controversial to a precedential degree among the great composers. Wagnerian scholar Dieter Borchmeyer has written:

"The merest glance at writings on Wagner, including the most recent ones on the composer's life and works, is enough to convince the most casual reader that he or she has wandered into a madhouse. Even serious scholars take leave of their senses when writing about Wagner and start to rant."[2]

There are three main areas of ongoing debate: Wagner's religious beliefs, his beliefs on racial supremacy, and his anti-semitism.

Religious beliefs

Wagner's own religious views were idiosyncratic. While he admired Jesus, Wagner insisted that Jesus was of Greek origin rather than Jewish. Like the Hellenistic Gnostics, he also argued that the Old Testament had nothing to do with the New Testament, that the God of Israel was not the same God as the father of Jesus, and that the Ten Commandments lacked the mercy and love of Christian teachings. Like many German Romantics, Schopenhauer above all, Wagner was also fascinated by Buddhism, and for many years contemplated composing a Buddhist opera, to be titled Die Sieger ("The Victors"), based on Sùrdûla Karnavadanaan, an avadana of the Buddha's last journey.

Aspects of Die Sieger were finally absorbed into Parsifal, which depicts a peculiar, "Wagnerized" version of Christianity; for instance, the ritual of transubstantiation in the Communion is subtly reinterpreted, becoming something closer to a pagan ritual than a Christian one. As occult historian Joscelyn Godwin stated, "it was Buddhism that inspired the philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer, and, through him, attracted Richard Wagner. This Orientalism reflected the struggle of the German Romantics, in the words of Leon Poliakov, to free themselves from Judeo-Christian fetters" (Arktos, 38). In short, Wagner adhered to an unconventional ethnic interpretation of the Christian writings that conformed to his German-Romantic aesthetic standards and tastes.

Aryanism

Some biographers have asserted that Wagner in his final years became convinced of the truth of the Aryanist philosophy of Arthur de Gobineau[3]. However the influence of Gobineau on Wagner's thought is debated [4][5] Wagner was first introduced to Gobineau in person in Rome in November of 1876. The two did not cross paths again until 1880, well after Wagner had completed the libretto for Parsifal, his opera most often accused of containing racist ideology, seemingly dispelling the notion of any strong influence of Gobineau on the opera. Although Gobineau's "Essai sur l'inégalité des races humaines" was written 25 years earlier, it seems that Wagner did not read it until October 1880.[6] There is evidence to suggest that Wagner was very interested in Gobineau's idea that Western society was doomed because of miscegenation between "superior" and "inferior" races. However, he does not seem to have subscribed to any belief in the superiority of the supposed Germanic or "Nordic" race.

Records state that Wagner's conversations with Gobineau during the philosopher's five-week stay at Wahnfried in 1881 were punctuated with frequent arguments. Cosima Wagner's diary entry for June 3rd recounts one exchange in which Wagner "positively exploded in favor of Christianity as compared to racial theory." Gobineau also believed, unlike Wagner, that the Irish (whom he considered a "degenerate" race) should be ruled by the English (a Nordic race), and that in order to have musical ability, one must have black ancestry.

Wagner subsequently wrote three essays in response to Gobineau's ideas: "Introduction to a Work of Count Gobineau," "Know Thyself," and "Heroism and Christianity" (all 1881). The "Introduction" is a short piece[7] written for the "Bayreuth BlÀtter" in which Wagner praises the Count's book:

- "We asked Count Gobineau, returned from weary, knowledge-laden wanderings among far distant lands and peoples, what he thought of the present aspect of the world; to-day we give his answer to our readers. He, too, had peered into an Inner: he proved the blood in modern manhood's veins, and found it tainted past all healing."

In "Know Thyself"[8] Wagner deals with the German people, whom Gobineau believes are the "superior" Aryan race. Wagner rejects the notion that the Germans are a race at all, and further proposes that we should look past the notion of race to focus on the human qualities ("das Reinmenschliche") common to all of us. In "Heroism and Christianity"[9], Wagner's proposes that Christianity could function to provide a moral harmonization of all races, and that it could be a unifying force in the world preferable to the physical unification of races by miscegenation:

- "Whilst yellow races have viewed themselves as sprung from monkeys, the white traced back their origin to gods, and deemed themselves marked out for rulership. It has been made quite clear that we should have no History of Man at all, had there been no movements, creations and achievements of the white men; and we may fitly take world-history as the consequence of these white men mixing with the black and yellow, and bringing them in so far into history as that mixture altered them and made them less unlike the white. Incomparably fewer in individual numbers than the lower races, the ruin of the white races may be referred to their having been obliged to mix with them; whereby, as remarked already, they suffered more from the loss of their purity than the others could gain by the ennobling of their bloodâŠ. If the noblest race's rulership and exploitation of the lower races, quite justified in a natural sense, has founded a sheer immoral system throughout the world, any equalising of them all by flat commixture decidedly would not conduct to an aesthetic state of things. To us Equality is only thinkable as based upon a universal moral concord, such as we can but deem true Christianity elect to bring about."

Gobineau stayed at Wahnfried again during May 1882, but did not engage in such extensive or heated debate with Wagner as on the previous occasion, as Wagner was largely occupied by the preparations for the premiere of Parsifal. Wagner's concerns over miscegenation occupied him until the very end of his life, and he was in the process of writing another essay, "On the Womanly in the Human Race" (1883)[10], at the time of his death. The work appears to have been intended as a meditation on the role of marriage in the creation of races:

"it is certain that the noblest white race is monogamic at its first appearance in saga and history, but marches toward its downfall through polygamy with the races which it conquers."

Wagner's writings on race would probably be considered unimportant were it not for the influence of his son-in-law Houston Stewart Chamberlain, who expanded on Wagner and Gobineau's ideas in his 1899 book The Foundations of the Nineteenth Century, a racist work extolling the Aryan ideal which later strongly influenced Adolf Hitler's ideas on race.[11]

Antisemitism

Wagner's views

Wagner frequently accused Jews, particularly Jewish musicians, of being a harmful alien element in German culture. His first and most controversial essay on the subject was "Das Judenthum in der Musik" ("Jewry in Music"), originally published under the pen-name "K. Freigedank" ("K. Freethought") in 1850 in the Neue Zeitschrift fĂŒr Musik. The essay purported to explain popular dislike of Jewish composers, such as Wagner's contemporaries (and rivals) Felix Mendelssohn and Giacomo Meyerbeer. Wagner wrote that the German people were repelled by Jews due to their alien appearance and behaviorâ"with all our speaking and writing in favor of the Jews' emancipation, we always felt instinctively repelled by any actual, operative contact with them." He argued that Jewish musicians were only capable of producing music that was shallow and artificial, because they had no connection to the genuine spirit of the German people.

In the conclusion to the essay, he wrote of the Jews that "only one thing can redeem you from the burden of your curse: the redemption of Ahasuerusâgoing under!" Although this has been taken to mean actual physical annihilation, in the context of the essay it seems to refer only to the eradication of Jewish separateness and traditions. Wagner advises Jews to follow the example of Ludwig Börne by abandoning Judaism. In this way Jews will take part in "this regenerative work of deliverance through self-annulment; then are we one and un-dissevered!"[12] Wagner was therefore calling for the assimilation of Jews into mainstream German culture and society - although there can be little doubt, from the words he uses in the essay, that this call was prompted at least as much by old-fashioned Jew-hatred as by a desire for social amelioration. (In the very first publication, the word here translated as 'self-annulment' was represented by the phrase 'self-annihilating, bloody struggle')[13]. The initial publication of the article attracted little attention, but Wagner republished it as a pamphlet under his own name in 1869, leading to several public protests at performances of Die Meistersinger von NĂŒrnberg. Wagner repeated similar views in several later articles, such as "What is German?" (1878).

Some biographers, such as Robert Gutman[14] have advanced the claim that Wagner's opposition to Jewry was not limited to his articles, and that the operas contained such messages. For example, characters such as Mime in the Ring and Sixtus Beckmesser in Die Meistersinger are supposedly Jewish stereotypes, though they are not explicitly identified as Jews. Such claims are disputed. The arguments supporting these purported "hidden messages" are often convoluted, and may be the result of biased over-interpretation. Wagner was not above putting digs and insults to specific individuals into his work, and it was usually obvious when he did. Wagner, over the course of his life, produced a huge amount of written material analyzing every aspect of himself, including his operas and his views on Jews (as well as practically every other topic under the sun); these purported messages are never mentioned.

Despite his very public views concerning Jewry, Wagner had several Jewish friends and colleagues. One of the most notable of these was Hermann Levi, a practising Jew and son of a Rabbi, whose talent was freely acknowledged by Wagner. Levi's position as Kapellmeister at Munich meant that he was to conduct the premiere of Parsifal, Wagner's last opera. Wagner initially objected to this and was quoted as saying that Levi should be baptized before conducting Parsifal. Levi however held Wagner in adulation, and was asked to be a pallbearer at the composer's funeral.

Nazi appropriation

Around the time of Wagner's death, European nationalist movements were losing the Romantic, idealistic egalitarianism of 1848, and acquiring tints of militarism and aggression, due in no small part to Bismarck's takeover and unification of Germany in 1871. After Wagner's death in 1883, Bayreuth increasingly became a focus for German nationalists attracted by the mythos of the operas, who came to be known as the Bayreuth circle. This group was endorsed by Cosima, whose anti-Semitism was considerably less complex and more virulent than Wagner's. One of the circle was Houston Stewart Chamberlain, the author of a number of 'philosophic' tracts which later became required Nazi reading. Chamberlain married Wagner's daughter, Eva. After the deaths of Cosima and Siegfried Wagner in 1930, the operation of the Festival fell to Siegfried's widow, English-born Winifred, who was a personal friend of Adolf Hitler. Hitler was a fanatical student and admirer of Wagner's ideology and music, and sought to incorporate it into his heroic mythology of the German nation (a nation that had no formal identity prior to 1871). Hitler held many of Wagner's original scores in his Berlin bunker during World War II, despite the pleadings of Wieland Wagner to have these important documents put in his care; the scores perished with Hitler in the final days of the war.

Many scholars have argued that Wagner's views, particularly his anti-Semitism and purported Aryan-Germanic racism, influenced the Nazis. These claims are disputed. Controversial historian Richard J. Evans suggests there is no evidence that Hitler even read any of Wagner's writings and further argues that Wagner's works do not inherently support Nazi notions of heroism. For example, Siegfried, the ostensible "hero" of the Ring cycle, may appear (and often does so in modern productions) a shallow and unappealing loutâalthough this is certainly not how Wagner himself conceived him; the opera's sympathies seem to lie instead with the world-weary womaniser Wotan. Many aspects of Wagner's personal philosophy would certainly have been unappealing to Nazis, such as his quietist mysticism and support for Jewish assimilation. For example, Goebbels banned Parsifal in 1939, shortly before the outbreak of the Second World War, due to the perceived pacifistic overtones of the opera.

For the most part, the Nazi fascination with Wagner was limited to Hitler, sometimes to the dismay of other high-ranking Nazi officials, including Goebbels. In 1933, for instance, Hitler ordered that each Nuremberg Rally open with a performance of the Meistersinger overture, and he even issued one thousand free tickets to Nazi functionaries. When Hitler entered the theater, however, he discovered that it was almost empty. The following year, those functionaries were ordered to attend, but they could be seen dozing off during the performance, so that in 1935, Hitler conceded and released the tickets to the public.

In general, while Wagner's music was often performed during the Third Reich, his popularity actually declined in favor of Italian composers such as Verdi and Puccini. By the 1938-1939 season, Wagner had only one opera in the list of 15 most popular operas of the season, with the list headed by Italian composer Ruggiero Leoncavallo's Pagliacci.[15]

Nevertheless, Wagner's operas have never been staged in the modern state of Israel, and the few instrumental performances that have occurred have provoked much controversy. Although his works are commonly broadcast on government-owned radio and television stations, attempts at staging public performances have been halted by protests, which have included protests from Holocaust survivors. For instance, after Daniel Barenboim conducted the Siegfried Idyll as an encore at the 2001 Israel Festival, a parliamentary committee urged a boycott of the conductor, and an initially scheduled performance of Die WalkĂŒre had to be withdrawn. On another occasion, Zubin Mehta played Wagner in Israel in spite of walkouts and jeers from the audience. One of the many ironies reflecting the complexities of Wagner and the responses his music provokes is that, like many German-speaking Jews of the pre-Hitler epoch, Theodore Herzl, a founder of modern Zionism, was an avid admirer of Wagner's work.

Notes

- â Bryan Magee. (2002). The Tristan Chord. (New York: Owl Books, ISBN 080507189X. (UK Title: Wagner and Philosophy. (Penguin Books Ltd, ISBN 0140295194)

- â Dieter Borchmeyer. (2003). Preface to Drama and the World of Richard Wagner. (Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691114978)

- â Robert Gutman. (1968). Richard Wagner: The Man, His Mind and His Music. (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1990. ISBN 0156776154), 418ff

- â Martin Gregor-Dellin. (1983) Richard Wagner: his life, his work, his Century. (William Collins, ISBN 0002166690), 468, 487.

- â Gobineau as the Inspiration of Parsifal. Retrieved February 11, 2009

- â Gutman, 1990, 406

- â Richard Wagner, 1881, Translated by William Ashton Ellis, Introduction to a work of Count Gobineau's. Retrieved February 11, 2009.

- â Richard Wagner, 1881, Translated by William Ashton Ellis, "Know Thyself". Retrieved February 11, 2009.

- â Richard Wagner, 1881, Translated by William Ashton Ellis, Hero-dom and Christendom. Retrieved February 11, 2009.

- â Richard Wagner, 1883, Translated by William Ashton Ellis, On the Womanly in the Human Race. Retrieved February 11, 2009.

- â The Foundations of the Nineteenth Century.hschamberlain.net.

- â Wagner, R. Judaism in Music

- â Wagner, R. Judaism in Music, note 37 Retrieved February 11, 2009.

- â Gutman, 1990,

- â Richard J. Evans. The Third Reich in Power, 1933-1939. (London: Penguin Press, ISBN 1594200742), 198-201.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Borchmeyer, Dieter. 2003. Preface to Drama and the World of Richard Wagner. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691114978.

- Evans, Richard J. 2005. The Third Reich in Power, 1933-1939. The Penguin Press, ISBN 1594200742.

- Gregor-Dellin, Martin. 1983. Richard Wagner: his life, his work, his Century. William Collins, ISBN 0002166690.

- Gutman, Robert. (1968). Richard Wagner: The Man, His Mind and His Music. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1990. ISBN 0156776154.

- Kavanaugh, Patrick. The Spiritual Lives of the Great Composers. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1992. ISBN 0310208068.

- Magee, Bryan 2002. The Tristan Chord. New York: Owl Books, ISBN 080507189X. UK Title: Wagner and Philosophy. Penguin Books Ltd, ISBN 0140295194.

- Saffle, Michael. 2001. Richard Wagner: A Guide to Research. London: Routledge, ISBN 0824056957.

- Schonberg, Harold C. The Lives of the Great Composers. New York: W.W. Norton and Co., 1970. ISBN 0393013022.

Further reading

- Burbidge, Peter, and Richard Sutton, eds. The Wagner Companion. 1979.

- Dahlhaus, C.; Mary Whitall, tr., Richard Wagner's Music Dramas.

- Dallas, Ian. The New Wagnerian. Granada: Freiburg Books, 1990. ISBN 844047475X.

- Lee, M. Owen. Wagner: The Terrible Man and His Truthful Art. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1998.

- Magee, B., Aspects of Wagner. Oxford University Press, 1988. ISBN 0192840126.

- May, Thomas. Decoding Wagner. Amadeus Press, 2004. ISBN 1574670972.

- Newman, Ernest. The Life of Richard Wagner. 1933. (Classic status, but still full of many valuable insights)

- Runciman, J.F., Wagner. 1913. here. Project Gutenberg.

- Scruton, Roger. Death-Devoted Heart: Sex and the Sacred in Wagner's 'Tristan and Isolde. 2003.

- Spencer, Stuart. Wagner Remembered. 2000.

- Stone, M., The Ring Disc: An Interactive Guide to Wagner's Ring Cycle. Media Cafe, 1997.

- Tanner, M., Wagner. Princeton University Press, 1995.

- Wagner, Cosima, Geoffrey Skelton, tr. Diaries. 1978.

- Wagner, Richard, Stewart Spencer and Barry Millington, eds. Selected Letters of Richard Wagner. 1987.

- Wagner, Richard, Andrew Gray, tr. My Life. 1992. ISBN 0106804816, far higher quality than the old anonymous translation.

External links

All links retrieved December 13, 2022.

- Bayreuth Festival

- The Richard Wagner Postcard-Gallery. A gallery of historic postcards with motives from Richard Wagner's operas.

- Better to know by Edward Said, Le Monde diplomatique

- The Wagner Tuba

- Works by Richard Wagner. Project Gutenberg

- 1869 Caricature of Richard Wagner by André Gill

- Free scores by Richard Wagner in the Werner Icking Music Archive

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.