Aesthetics

Aesthetics (also spelled esthetics) is a branch of philosophy; it is a species of value theory or axiology, which is the study of sensory or sensori-emotional values, sometimes called judgments of sentiment and taste. Aesthetics is closely associated with the philosophy of art. Aesthetics is sometimes called "the study of beauty," but that proposed definition will not do because some of the things that many people find aesthetically valuable or good or noteworthy are not beautiful in any usual or reasonable sense of the term "beautiful."

The term aesthetics comes from the Greek αጰÏΞηÏÎčÎșÎź "aisthetike" and was coined by the philosopher Alexander Gottlieb Baumgarten in 1735 to mean "the science of how things are known via the senses."[1] The term aesthetics was used in German, shortly after Baumgarten introduced its Latin form (Aesthetica), but was not widely used in English until the beginning of the nineteenth century. However, much the same study was called studying the "standards of taste" or "judgments of taste" in English, following the vocabulary set by David Hume prior to the introduction of the term "aesthetics."

Today the word "aesthetics" may mean (1) the study of all the aesthetic phenomena, (2) the study of the perception of such phenomena, (3), the study of art or what is considered to be artistically worthwhile or notable or "good," as a specific expression of what is perceived as being aesthetic.

What is an aesthetic judgment?

Judgments of aesthetic value rely on our ability to discriminate at a sensory level. Aesthetics examines what makes something beautiful, sublime, disgusting, fun, cute, silly, entertaining, pretentious, stimulating, discordant, harmonious, boring, humorous, or tragic.

Immanuel Kant, writing in 1790, observed of a man that "If he says that canary wine is agreeable he is quite content if someone else corrects his terms and reminds him to say instead: It is agreeable to me," because "Everyone has his own taste (of sense)." The case of "beauty" is different from mere "agreeableness" because, "If he proclaims something to be beautiful, then he requires the same liking from others; he then judges not just for himself but for everyone, and speaks of beauty as if it were a property of things."[2]

Aesthetic judgments usually go beyond sensory discrimination. For David Hume, delicacy of taste is not merely "the ability to detect all the ingredients in a composition," but also our sensitivity "to pains as well as pleasures, which escape the rest of mankind."[3] Thus, sensory discrimination is linked to capacity for pleasure. For Kant "enjoyment" is the result when pleasure arises from sensation, but judging something to be "beautiful" has a third requirement: sensation must give rise to pleasure by engaging our capacities of reflective contemplation.[2] Judgments of beauty are sensory, emotional, and intellectual all at once.

What factors are involved in an aesthetic judgment?

Judgments of aesthetic value seem often to involve many other kinds of issues as well. Responses such as disgust show that sensory detection is linked in instinctual ways to facial expressions, and even behaviors like the gag reflex. Yet disgust can often be a learned or cultural issue too; as Darwin pointed out, seeing a stripe of soup in a man's beard is disgusting even though neither soup nor beards are themselves disgusting. Aesthetic judgments may be linked to emotions or, like emotions, partially embodied in our physical reactions. Seeing a sublime view of a landscape may give us a reaction of awe, which might manifest physically as an increased heart rate or widened eyes. These subconscious reactions may even be partly constitutive of what makes our judgment a judgment that the landscape is sublime.

Likewise, aesthetic judgments may be culturally conditioned to some extent. Victorians in Britain often saw African sculpture as ugly, but just a few decades later, Edwardian audiences saw the same sculptures as being beautiful.[4] Evaluations of beauty may well be linked to desirability, perhaps even to sexual desirability. Thus, judgments of aesthetic value can become linked to judgments of economic, political, or moral value. We might judge a Lamborghini automobile to be beautiful partly because it is desirable as a status symbol, or we might judge it to be repulsive partly because it signifies for us over-consumption and offends our political or moral values.[5]

Aesthetic judgments can often be very fine-grained and internally contradictory. Likewise aesthetic judgments seem often to be at least partly intellectual and interpretative. It is what a thing means or symbolizes for us that is often what we are judging. Modern aestheticians have asserted that will and desire were almost dormant in aesthetic experience yet preference and choice have seemed important aesthetics to some twentieth-century thinkers.[7] Thus aesthetic judgments might be seen to be based on the senses, emotions, intellectual opinions, will, desires, culture, preferences, values, subconscious behavior, conscious decision, training, instinct, sociological institutions, or some complex combination of these, depending on exactly which theory one employs.

Anthropology, with the savanna hypothesis proposed by Gordon Orians, predicts that some of the positive aesthetics that people have are based on innate knowledge of productive human habitats. The savanna hypothesis is confirmed by evidence. It had been shown that people prefer and feel happier looking at trees with spreading forms much more than looking at trees with other forms, or non-tree objects; also bright green colors, linked with healthy plants with good nutrient qualities, were more calming than other tree colors, including less bright greens and oranges.[8]

Are different art forms beautiful, disgusting, or boring in the same way?

Another major topic in the study of aesthetic judgment is how they are unified across art forms. We can call a person, a house, a symphony, a fragrance, and a mathematical proof beautiful. What characteristics do they share that give them that status? What possible feature could a proof and a fragrance both share in virtue of which they both count as beautiful? What makes a painting beautiful may be quite different from what makes music beautiful; this suggests that each art form has its own system for the judgment of aesthetics.[9]

Or, perhaps the identification of beauty is a conditioned response, built into a culture or context. Is there some underlying unity to aesthetic judgment and is there some way to articulate the similarities of a beautiful house, beautiful proof, and beautiful sunset? Likewise there has been long debate on how perception of beauty in the natural world, especially including perceiving the human form as beautiful, is supposed to relate to perceiving beauty in art or cultural artifacts. This goes back at least to Kant, with some echoes even in Saint Bonaventure.

Aesthetics and ethics

Some writers and commentators have made a link between aesthetic goodness and ethical or moral goodness. But close attention to what is often or frequently held to be aesthetically good or notable or worthwhile will show that the connection between aesthetic goodness and ethical or moral goodness is, if it exists at all, only partial and only occurs sometimes.

Pablo Picasso's Guernicaâarguably the greatest or most important painting of the twentieth centuryâis based on the aerial bombing of the town of Guernica in the Basque area of Spain on April 26, 1937, by the Nazis during the Spanish Civil War. It depicts animals and people who are torn, ripped, broken, killed, and screaming in agony and horror; those are not things that are ethically good.

After the invention of photography, one of its important uses both as document and as art was showing war and its results. Another important subject of painting, photography, cinema, and literature is the presentation of crime and murder. Some of the greatest poetry and literature and music depict or are based on human suffering, infidelity and adultery, despair, drunkenness and alcoholism and drug addiction, rape, depravity, and other unethical things. Critical consideration of the film Triumph of the Will, by Leni Riefenstahl, presents us with this problem in an extreme way: The film itself is an aesthetic and cinematic masterpiece, yet it functioned as propaganda in favor of Hitler and the Nazis. So what are we to make of it, and how should we respond?

In addition, there is no necessary connection between aesthetic or artistic genius or talent or achievement, and ethical goodness in the artist. Picasso and Richard Wagner are only two of many similar examples that could be given. Picasso in painting and Richard Wagner in music reached the pinnacle of aesthetic achievement and taste, but, as human beings, both led lives and behaved in ways that are usually held to be highly unethical.

Are there aesthetic universals?

Is there anything that is or can be universal in aesthetics, beyond barriers of culture, custom, nationality, education and training, wealth and poverty, religion, and other human differences? At least tentatively the answer seems to be yes. Either coming from God in creation, or arising by the process of naturalistic evolutionâtake your pick as to which of those you think is correctâsome universal characteristics seem to by shared by all humans. Some scenes and motifsâsome examples are mother with child, hero overcoming adversity and succeeding, demise of the arrogant or the oppressorâappeal nearly universally, as do certain musical intervals and harmonies.

The philosopher Denis Dutton identified seven universal signatures in human aesthetics:[10]

- Expertise or virtuosity. Technical artistic skills are cultivated, recognized, and admired.

- Nonutilitarian pleasure. People enjoy art for art's sake, and don't demand that it keep them warm or put food on the table.

- Style. Artistic objects and performances satisfy rules of composition that place them in a recognizable style.

- Criticism. People make a point of judging, appreciating, and interpreting works of art.

- Imitation. With a few important exceptions like music and abstract painting, works of art simulate experiences of the world.

- Special focus. Art is set aside from ordinary life and made a dramatic focus of experience.

- Imagination. Artists and their audiences entertain hypothetical worlds in the theater of the imagination.

Increasingly, academics in both the sciences and the humanities are looking to evolutionary psychology and cognitive science in an effort to understand the connection between psychology and aesthetics. Aside from Dutton, others exploring this realm include Brian Boyd, Joseph Carroll, Nancy Easterlin, David Evans, Jonathan Gottschall, Paul Hernadi, Patrick Hogan, Elaine Scarry, Wendy Steiner, Robert Storey, Frederick Turner, and Mark Turner.

Aesthetics and the philosophy of art

It is not uncommon to find aesthetics used as a synonym for the philosophy of art, but others have realized that we should distinguish between these two closely related fields.

What counts as "art?"

How best to define the term âartâ is a subject of much contention; many books and journal articles have been published arguing over even the basics of what we mean by the term âart.â[11][12] Theodor Adorno claimed in 1969: âIt is self-evident that nothing concerning art is self-evident any more.â[4] Artists, philosophers, anthropologists, psychologists and programmers all use the notion of art in their respective fields, and give it operational definitions that are not very similar to each other. Further it is clear that even the basic meaning of the term "art" has changed several times over the centuries, and has changed within the twentieth century as well.

The main recent sense of the word âartâ is roughly as an abbreviation for "creative art" or âfine art.â Here we mean that skill is being used to express the artistâs creativity, or to engage the audienceâs aesthetic sensibilities in some way. Often, if the skill is being used in a lowbrow or practical way, people will consider it a craft instead of art, yet many thinkers have defended practical and lowbrow forms as being just as much art as the more lofty forms. Likewise, if the skill is being used in a commercial or industrial way it may be considered design, rather than art, or contrariwise these may be defended as art forms, perhaps called "applied art." Some thinkers, for instance, have argued that the difference between fine art and applied art has more to do with value judgments made about the art than any clear definitional difference.[13]

Even as late as 1912 it was normal in the West to assume that all art aims at beauty, and thus that anything that was not trying to be beautiful could not count as art. The cubists, dadaists, Igor Stravinsky, and many later art movements struggled against this conception that beauty was central to the definition of art, with such success that, according to Arthur Danto, âBeauty had disappeared not only from the advanced art of the 1960s but from the advanced philosophy of art of that decade as well.â[4] Perhaps some notion like âexpressionâ (in Benedetto Croceâs theories) or âcounter-environmentâ (in Marshall McLuhanâs theory) can replace the previous role of beauty.

Perhaps (as in William Kennick's theory) no definition of art is possible anymore. Perhaps art should be thought of as a cluster of related concepts in a Wittgensteinian fashion (as in Morris Weitz or Joseph Beuys). Another approach is to say that âartâ is basically a sociological category, that whatever art schools and museums and artists get away with is considered art regardless of formal definitions. This "institutional definition of art" has been championed by George Dickie. Most people did not consider the depiction of a Brillo Box or a store-bought urinal to be art until Andy Warhol and Marcel Duchamp (respectively) placed them in the context of art (namely, the art gallery), which then provided the association of these objects with the values that define art.

Proceduralists often suggest that it is the process by which a work of art is created or viewed that makes it art, not any inherent feature of an object, or how well received it is by the institutions of the art world after its introduction to society at large. For John Dewey, for instance, if the writer intended a piece to be a poem, it is one whether other poets acknowledge it or not. Whereas if exactly the same set of words was written by a journalist, intending them as shorthand notes to help him write a longer article later, these would not be a poem. Leo Tolstoy, on the other hand, claims that what makes something art or not is how it is experienced by its audience, not by the intention of its creator. Functionalists like Monroe Beardsley argue that whether or not a piece counts as art depends on what function it plays in a particular context; the same Greek vase may play a non-artistic function in one context (carrying wine), and an artistic function in another context (helping us to appreciate the beauty of the human figure).

What should we judge when we judge art?

Art can be confusing and difficult to deal with at the metaphysical and ontological levels as well as at the value theory level. When we see a performance of Hamlet, how many works of art are we experiencing, and which should we judge? Perhaps there is only one relevant work of art, the whole performance, which many different people have contributed to, and which will exist briefly and then disappear. Perhaps the manuscript by Shakespeare is a distinct work of art from the play by the troupe, which is also distinct from the performance of the play by this troupe on this night, and all three can be judged, but are to be judged by different standards.

Perhaps every person involved should be judged separately on his or her own merits, and each costume or line is its own work of art (with perhaps the director having the job of unifying them all). Similar problems arise for music, film and even painting. Am I to judge the painting itself, the work of the painter, or perhaps the painting in its context of presentation by the museum workers?

These problems have been made even thornier by the rise of conceptual art since the 1960s. Warholâs famous Brillo Boxes are nearly indistinguishable from actual Brillo boxes at the time. It would be a mistake to praise Warhol for the design of his boxes (which were designed by James Harvey), yet the conceptual move of exhibiting these boxes as art in a museum together with other kinds of paintings is Warhol's. Are we judging Warholâs concept? His execution of the concept in the medium? The curatorâs insight in letting Warhol display the boxes? The overall result? Our experience or interpretation of the result? Ontologically, how are we to think of the work of art? Is it a physical object? Several objects? A class of objects? A mental object? A fictional object? An abstract object? An event? Those questions no longer seem to have clear or unambiguous answers.

What should art be like?

Many goals have been argued for art, and aestheticians often argue that some goal or another is superior in some way. Clement Greenberg, for instance, argued in 1960 that each artistic medium should seek that which makes it unique among the possible mediums and then purify itself of anything other than expression of its own uniqueness as a form.[9] The dadaist Tristan Tzara on the other hand saw the function of art in 1918 as the destruction of a mad social order. âWe must sweep and clean. Affirm the cleanliness of the individual after the state of madness, aggressive complete madness of a world abandoned to the hands of bandits.â[14] Formal goals, creative goals, self-expression, political goals, spiritual goals, philosophical goals, and even more perceptual or aesthetic goals have all been popular pictures of what art should be like.

What is the value of art?

Closely related to the question of what art should be like is the question of what its value is. Is art a means of gaining knowledge of some special kind? Does it give insight into the human condition? How does art relate to science or religion? Is art perhaps a tool of education, or indoctrination, or enculturation? Does art make us more moral? Can it uplift us spiritually? â the answers to those two questions are surely, "Yes, sometimes, but only sometimes." Is art perhaps politics by other means? Is there some value to sharing or expressing emotions? Might the value of art for the artist be quite different than it is for the audience? â Again, the answers to those questions too are "Sometimes, but only sometimes."

Might the value of art to society be quite different than its value to individuals? Do the values of arts differ significantly from form to form? Working on the intended value of art tends to help define the relations between art and other endeavors. Art clearly does have spiritual goals in many settings, but then what exactly is the difference between religious art and religion per se? â the answer seems to be that religious art is a subset of religion, per se. But is every religious ritual also a piece of performance art, so that religious ritual is a subset of art? The answer seems to be yes.

History of aesthetics

Ancient aesthetics

We have examples of pre-historic art, but they are rare, and the context of their production and use is not very clear, so we can do little more than guess at the aesthetic doctrines that guided their production and interpretation.

Ancient art was largely, but not entirely, based on the six great ancient civilizations: Ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, Ancient Greece, Ancient Rome, Indus Valley Civilization, and China. Each of these centers of early civilization developed a unique and characteristic style in its art. Greece had the most influence on the development of aesthetics in the West. This period of Greek art saw a veneration of the human physical form and the development of corresponding skills to show musculature, poise, beauty, and anatomically correct proportions.

Ancient Greek philosophers initially felt that aesthetically appealing objects were beautiful in and of themselves. Plato felt that beautiful objects incorporated proportion, harmony, and unity among their parts. Similarly, in his Metaphysics, Aristotle found that the universal elements of beauty were order, symmetry, and definiteness.

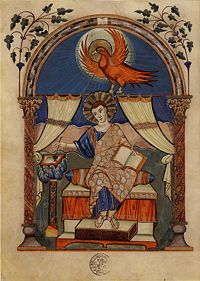

Western medieval aesthetics

Surviving medieval art is highly religious in focus, and was usually funded by the Roman Catholic Church, powerful ecclesiastical individuals, or wealthy secular patrons. Often the pieces have an intended liturgical function, such as altar pieces or statuary. Figurative examination was typically not an important goal, but being religiously uplifting was.

One reason for the prevalence of religious art, including dance, theater, and other performance arts during the medieval period, was that most people were illiterate and such art presentations were used to teach them the content of their religion.

Reflection on the nature and function of art and aesthetic experiences follows similar lines. St. Bonaventureâs Retracing the Arts to Theology is typical and discusses the skills of the artisan as gifts given by God for the purpose of disclosing God to mankind via four âlightsâ: the light of skill in mechanical arts which discloses the world of artifacts, as guided by the light of sense perception which discloses the world of natural forms, as guided by the light of philosophy which discloses the world of intellectual truth, as guided by the light of divine wisdom which discloses the world of saving truth.

As the medieval world shifts into the Renaissance art again returns to focus on this world and on secular issues of human life. The philosophy of art of the ancient Greeks and Romans is re-appropriated.

Modern aesthetics

From the late seventeenth to the early twentieth century Western aesthetics underwent a slow revolution into what is often called modernism. German and British thinkers emphasized beauty as the key component of art and of the aesthetic experience, and saw art as necessarily aiming at beauty.

For Alexander Gottlieb Baumgarten aesthetics is the science of the sense experiences, a younger sister of logic, and beauty is thus the most perfect kind of knowledge that sense experience can have. For Immanuel Kant the aesthetic experience of beauty is a judgment of a subjective but universal truth, since all people should agree that âthis rose is beautifulâ if, in fact, it is. However, beauty cannot be reduced to any more basic set of features. For Friedrich Schiller aesthetic appreciation of beauty is the most perfect reconciliation of the sensual and rational parts of human nature.

For Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel all culture is a matter of "absolute spirit" coming to be manifest to itself, stage by stage. Art is the first stage in which the absolute spirit is manifest immediately to sense-perception, and is thus an objective rather than subjective revelation of beauty. For Arthur Schopenhauer aesthetic contemplation of beauty is the most free that the pure intellect can be from the dictates of will; here we contemplate perfection of form without any kind of worldly agenda, and thus any intrusion of utility or politics would ruin the point of the beauty.

The British were largely divided into intuitionist and analytic camps. The intuitionists believed that aesthetic experience was disclosed by a single mental faculty of some kind. For the Earl of Shaftesbury this was identical to the moral sense, beauty just is the sensory version of moral goodness.

For philosopher Francis Hutcheson beauty is disclosed by an inner mental sense, but is a subjective fact rather than an objective one. Analytic theorists such as Lord Kames, William Hogarth, and Edmund Burke hoped to reduce beauty to some list of attributes. Hogarth, for example, thought that beauty consists of (1) fitness of the parts to some design; (2) variety in as many ways as possible; (3) uniformity, regularity or symmetry, which is only beautiful when it helps to preserve the character of fitness; (4) simplicity or distinctness, which gives pleasure not in itself, but through its enabling the eye to enjoy variety with ease; (5) intricacy, which provides employment for our active energies, leading the eye "a wanton kind of chase"; and (6) quantity or magnitude, which draws our attention and produces admiration and awe. Later analytic aestheticians strove to link beauty to some scientific theory of psychology (such as James Mill) or biology (such as Herbert Spencer).

Post-modern aesthetics

The challenge, issued by early twentieth century artists, poets and composers, to the assumption that beauty was central to art and aesthetics led, in response, to various attempts since then to define a post-modern aesthetics.

Benedetto Croce suggested that âexpressionâ is central in the way that beauty was once thought to be central. George Dickie suggested that the sociological institutions of the art world were the glue binding art and sensibility into unities. Marshall McLuhan suggested that art always functions as a "counter-environment" designed to make visible what is usually invisible about a society. Theodor Adorno felt that aesthetics could not proceed without confronting the role of the culture industry in the commodification of art and aesthetic experience. Art critic Hal Foster attempted to portray the reaction against beauty and Modernist art in The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture. Arthur Danto described this reaction as "kalliphobia" (after the Greek word for beauty kalos)[15]

Jean-François Lyotard re-invokes the Kantian distinction between taste and the sublime. Sublime painting, unlike kitsch realism, "âŠwill enable us to see only by making it impossible to see; it will please only by causing pain."[16]

Islamic aesthetics

Islamic art is perhaps the most accessible manifestation of a complex civilization that often seems enigmatic to outsiders. Through its use of color and its balance between design and form, Islamic art creates an immediate visual impact. Its aesthetic appeal transcends distances in time and space, as well as differences in language, culture, and creed. For an American audience a visit to the Islamic galleries of a museum such as the Los Angeles County Museum of Art can represent the first step toward penetrating the history of a religion and a culture that are often in the news but are little understood.

Further, Allah was taken to be immune to representation via imagery, so nonrepresentational imagery was developed to a high degree. Thus Islamic aesthetics emphasized the decorative function of art, or its religious functions via non-representational forms. Geometric patterns, floral patterns, arabesques, and abstract forms were common. Order and unity were common themes.

Calligraphy is central to Islamic art. In fact, it is the most important and pervasive element in Islamic art. Because of its association with the Qur'an, the Muslim holy book written in Arabic, calligraphy is considered in Islamic society to be the noblest form of art. A concern with the beauty of writing extended from the Qur'an to all forms of art, including secular manuscripts, as well as inscriptions applied to metalwork, pottery, stone, glass, wood, and textiles. This concern with calligraphy extended to non-Arabic speaking peoples within the Islamic world too, peoples whose languagesâsuch as Persian, Turkish, and Urduâwere written in the Arabic script.

Islamic art is also characterized by a tendency to use patterns made of complex geometric or vegetal elements or patterns (such as the arabesque). This type of nonrepresentational decoration may have been developed to such a high degree in Islamic art because of the absence of figural imagery, at least within a religious context. These repetitive patterns are believed by some people to lead to contemplation of the infinite nature of God.

Figural imagery is also an important aspect of Islamic art, occurring mostly in secular and courtly arts. These are found in a wide variety of media and in most periods and places in which Islam flourished. But representational imagery almost always occurs only in a private context, and figurative art is excluded from religious monuments and contexts. Forbidding of representational art from religious contexts comes about because of Islamic hostility concerning things that could be considered to be idols; those are explicitly forbidden by the Qur'an.

A distinction can be drawn here between Western and Islamic art. In Western art, painting and sculpture are preeminent, but in Islamic cultures decorative arts predominate. These decorative arts were expressed in inlaid metal and stone work, textiles and carpets, illuminated manuscripts, glass, ceramics, and carved wood and stone.

Royal patronage was important for many Islamic arts. Rulers were responsible for constructing mosques and other religious buildings, and Islamic arts were expressed in those structures and their accoutrements. Royal patronage also extended to secular arts.

Indian aesthetics

Indian art evolved with an emphasis on inducing special spiritual or philosophical states in the audience, or with representing them symbolically. According to Kapila Vatsyayan, Classical Indian architecture, Indian sculpture, Indian painting, Indian literature (kaavya), Indian music, and Indian dance "evolved their own rules conditioned by their respective media, but they shared with one another not only the underlying spiritual beliefs of the Indian religio-philosophic mind, but also the procedures by which the relationships of the symbol and the spiritual states were worked out in detail."

Chinese aesthetics

Chinese art has a long history of varied styles and emphases. In ancient times philosophers were already arguing about aesthetics, and Chinese aesthetics has been influenced by Daoism, Confucianism, and Buddhism. The basic assumption of Chinese aesthetics is that the phenomenal world mirrors the way of Dao or nature. The Dao is not something separate, but it is a manifestation of the pattern of the natural world, so the human must understand the Dao and act in accordance with it.

This is an organic view of nature in that it includes all reality, there is no separate transcendent realm. Heaven, earth, and humans form a unit. Moreover, nature itself is self-creative, and results in beauty and harmony.

In this view all thingsâincluding rocks and waterâhave vitality or qi, the âbreathâ of life. All phenomena are organically interrelated., and the world is a continuous field of qi, with each phenomenon not a separate thing but rather a temporary form within it, like a whirlpool in a stream.

The purpose of art, then, was to draw out the spirit of phenomena, instead of depicting a surface reality. Painters or sculptors are supposed to capture the specific qi of a thing, and if the artist succeeds in this, then the artwork itself will exhibit qi. In doing so, the artist is a participant in the creativity of nature.

To do this, according to Chinese theory, the artist needs to go through meditative practices that free him from attachment to a separate self and its desires, and that allow him to concentrate on the subject until he achieves a direct communion with it. Communing with nature in this way is possible because we humans are part of nature and thus not ontologically separate from or different from it.

A major concern of Chinese aesthetics was, thus, the relationship between self and nature; inner and outer. Chinese saw nature as continuing give and take of stimulus and response among all things, including humans. This gives rise to emotional response, and it was assumed that there is a strong correlation between what is experienced and the emotional response to it. [17]

Confucius emphasized the role of the arts and humanities (especially music and poetry) in broadening human nature and aiding âliâ (etiquette, the rites) in bringing us back to what is essential about humanity. His opponent Mozi, however, argued that music and fine arts were classist and wasteful, benefiting the rich but not the common peopleâan attitude that would be expressed again by the Marxists in the twentieth century.

By the fourth century C.E., artists were debating in writing over the proper goals of art as well. Gu Kaizhi has three surviving books on this theory of painting, for example, and it is not uncommon to find later artist/scholars who both create art and write about the creating of art. Religious and philosophical influence on art was common (and diverse) but never universal; it is easy to find art that largely ignores philosophy and religion in almost every Chinese time period.

African aesthetics

African art existed in many forms and styles, and with fairly little influence from outside Africa. Most of it followed traditional forms and the aesthetic norms were handed down orally as well as written. Sculpture and performance art are prominent, and abstract and partially abstracted forms are valued, and were valued long before influence from the Western tradition began in earnest. The Nok culture is testimony to this. The mosque of Timbuktu shows that specific areas of Africa developed unique aesthetics.

Although Africa is a large continent with many different peoples and diverse standards of art and beauty, there are certain identifiable patterns that seem to prevail across those differences.

Susan Vogel from the New York Center for African Art described an "African aesthetic" in African artwork as having the following characteristics:[18]

- Luminosity â shiny smooth surfaces, representing healthy skin.

- Youthfulness â sculptures commonly depict youthful figures, as illness and deformity are considered to be signs of evil.

- Self-composure â the subject is controlled, proud, and "cool."

- Clarity of form and detail, complexity of composition, balance and symmetry, smoothness of finish

- Resemblance to a human being

Aesthetics in some particular fields and art forms

Film, television, and video

Film combines many diverse disciplines, each of which may have its own rules of aesthetics. The aesthetics of cinematography are partly related to still photography, but the movement of the subject(s), or the camera and the fact that the result is a moving picture experience that takes place over time are important additions. (See the article "Cinematography.") Sound recording, editing, and mixing are other, highly important areas of film and film aesthetics, as is the use of a musical score. As in theater, art direction in the design of the sets and shooting locations also applies, as well as costume design and makeup. All of these disciplines are closely inter-twined and must be brought together by the aesthetic sensibilities of the film director.

Film editing (known in French as montage) is probably the one discipline unique to film, video, and television. The timing, rhythm and progression of shots form the ultimate composition of the film. This procedure is one of the most critical element of post production, and incorporates sound editing and mixing, as well as the design and execution of digital and other special effects.

In the case of a video installation, the method of presentation becomes critical. The work may be screened on a simple monitor or on many, be projected on a wall or other surface, or incorporated into a larger sculptural installation. A video installation may involve sound, with similar considerations to be made based on speaker design and placement, volume, and tone.

Two-dimensional and plastic arts

Aesthetic considerations within the visual arts are usually associated with the sense of vision. A painting or sculpture, however, is also perceived spatially by recognized associations and context, and even to some extent by the senses of smell, hearing, and touch. The form of the work can be subject to an aesthetic as much as the content.

In painting, the aesthetic convention that we see a three-dimensional representation rather than a two-dimensional canvas is so well understood that most people do not realize that they are making an aesthetic interpretation. This notion is central to the artistic movement known as abstract impressionism.

In the United States during the postwar period, the "push-pull" theories of Hans Hofmann, positing a relation between color and perceived depth, strongly influenced a generation of prominent abstract painters, many of whom studied under Hofmann and were generally associated with abstract expressionism. Hofmann's general attitude toward abstraction as virtually a moral imperative for the serious painter was also extremely influential.

Some aesthetic effects available in visual arts include variation, juxtaposition, repetition, field effects, symmetry/asymmetry, perceived mass, subliminal structure, linear dynamics, tension and repose, pattern, contrast, perspective, two and three dimensionality, movement, rhythm, unity/Gestalt, matrixiality, and proportion.

Cartography and map design

Aesthetics in cartography relates to the visual experience of map reading and can take two forms: responses to the map itself as an aesthetic object (e.g., through detail, color, and form) and also the subject of the map symbolized, often the landscape (e.g., a particular expression of terrain which forms an imagined visual experience of the aesthetic).

Cartographers make aesthetic judgments when designing maps to ensure that the content forms a clear expression of the theme(s). Antique maps are perhaps especially revered due to their aesthetic value, which may seem to be derived from their styles of ornamentation. As such, aesthetics are often wrongly considered to be a by-product of design. If it is taken that aesthetic judgments are produced within a certain social context, they are fundamental to the cartographer's symbolization and as such are integral to the function of maps.

Music

Some of the aesthetic elements expressed in music include lyricism, harmony and dissonance, hypnotism, emotiveness, temporal dynamics, volume dynamics, resonance, playfulness, color, subtlety, elatedness, depth, and mood. Aesthetics in music are often believed to be highly sensitive to their context: what sounds good in modern rock music might sound terrible in the context of the early baroque age. Moreover the history of music has numerous examples of composers whose work was considered to be vulgar, or ugly, or worse on its first appearance, but that became an appreciated and popular part of the musical canon later on.

Performing arts

Performing arts appeal to our aesthetics of storytelling, grace, balance, class, timing, strength, shock, humor, costume, irony, beauty, drama, suspense, and sensuality. Whereas live stage performance is usually constrained by the physical reality at hand, film performance can further add the aesthetic elements of large-scale action, fantasy, and a complex interwoven musical score. Performance art often consciously mixes the aesthetics of several forms. Role-playing games are sometimes seen as a performing art with an aesthetic structure of their own, called role-playing game (RPG) theory.

Literature

In poetry, short stories, novels and non-fiction, authors use a variety of techniques to appeal to our aesthetic values. Depending on the type of writing an author may employ rhythm, illustrations, structure, time shifting, juxtaposition, dualism, imagery, fantasy, suspense, analysis, humor/cynicism, thinking aloud, and other means.

In literary aesthetics, the study of "effect" illuminates the deep structures of reading and receiving literary works. These effects may be broadly grouped by their modes of writing and the relationship that the reader assumes with time. Catharsis is the effect of dramatic completion of action in time. Kairosis is the effect of novels whose characters become integrated in time. Kenosis is the effect of lyric poetry which creates a sense of emptiness and timelessness.

Gastronomy

Although food is a basic and frequently experienced commodity, careful attention to the aesthetic possibilities of foodstuffs can turn eating into gastronomy. Chefs inspire our aesthetic enjoyment through the visual sense using color and arrangement; they inspire our senses of taste and smell using spices and seasonings, diversity/contrast, anticipation, seduction, and decoration/garnishes.

The aesthetics of drinks and beverages and their appreciation, including non-alcoholic and alcoholic drinks, liquors and spirits, beers, and especially wines, is a huge field with specialized aesthetic and other considerations, vocabularies, experts in particular fields, and agreements and disagreements among connoisseurs, publications and literature, industries, etc. In regard to drinking water, there are formal criteria for aesthetic value including odor, color, total dissolved solids, and clarity. There are numerical standards in the United States for acceptability of these parameters.

Mathematics

The aesthetics of mathematics are often compared with music and poetry. Hungarian mathematician Paul ErdĆs expressed his views on the indescribable beauty of mathematics when he said: "Why are numbers beautiful? It's like asking 'why is Beethoven's Ninth Symphony beautiful?'" Mathematics and numbers appeal to the "senses" of logic, order, novelty, elegance, and discovery. Some concepts in mathematics with specific aesthetic application include sacred ratios in geometry (with applications to architecture), the intuitiveness of axioms, the complexity and intrigue of fractals, the solidness and regularity of polyhedra, and the serendipity of relating theorems across disciplines.

Neuroesthetics

Cognitive science has also considered aesthetics, with the advent of neuroesthetics, pioneered by Semir Zeki, which seeks to explain the prominence of great art as an embodiment of biological principles of the brain, namely that great works of art capture the essence of things just as vision and the brain capture the essentials of the world from the ever-changing stream of sensory input. (See also Vogelkop Bowerbird.)

Industrial design

Industrial Design: Designers heed many aesthetic qualities to improve the marketability of manufactured products: smoothness, shininess/reflectivity, texture, pattern, curviness, color, simplicity, usability, velocity, symmetry, naturalness, and modernism. The staff of the design aesthetics section of an industry or company focuses on design, appearance, and the way people perceive products. Design aesthetics is interested in the appearance of products; the explanation and meaning of this appearance is studied mainly in terms of social and cultural factors. The distinctive focus of the section is research and education in the field of sensory modalities in relation to product design. These fields of attention generate design considerations that enable engineers and industrial designers to design products, systems, and services, and match them to the correct field of use.

Architecture and interior design

Although structural integrity, cost, the nature of building materials, and the functional utility of the building contribute heavily to the design process, architects can still apply aesthetic considerations to buildings and related architectural structures. Common aesthetic design principles include ornamentation, edge delineation, texture, flow, solemnity, symmetry, color, granularity, the interaction of sunlight and shadows, transcendence, and harmony.

Interior designers, being less constrained by structural concerns, have a wider variety of applications to appeal to aesthetics. They may employ color, color harmony, wallpaper, ornamentation, furnishings, fabrics, textures, lighting, various floor treatments, as well as adhere to aesthetic concepts such as feng shui.

Landscape design

Landscape designers draw upon design elements such as axis, line, landform, horizontal and vertical planes, texture, and scale to create aesthetic variation within the landscape. Additionally, they usually make use of aesthetic elements such as pools or fountains of water, plants, seasonal variance, stonework, fragrance, exterior lighting, statues, and lawns.

Fashion design

Fashion designers use a variety of techniques to allow people to express themselves by way of their clothing. To create wearable personality designers use fabric, cut, color, scale, texture, color harmony, distressing, transparency, insignia, accessories, beading, and embroidery. Some fashions incorporate references to the past, while others attempt to innovate something completely new or different, and others are small variations on received designs or motifs.

Notes

- â Peter Kivy (ed.), The Blackwell Guide to Aesthetics (Malden, MA: Blackwell Pub., 2004, ISBN 0631221301).

- â 2.0 2.1 Immanuel Kant, J.H. Bernard (transl.). Critique of Judgement (Franklin Classics, 2018, ISBN 978-0342995394).

- â David Hume, "Of the Standard of Taste." Essays Moral Political and Literary (Liberty Fund Inc., 1985. ISBN 978-0865970564).

- â 4.0 4.1 4.2 Arthur Danto, The Abuse of Beauty (Chicago: Open Court, 2003, ISBN 0812695399).

- â Carolyn Korsmeyer (ed.), Aesthetics: The Big Questions (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers, 1998, ISBN 0631205934).

- â Konrad Lorenz, "Part and Parcel in Animal and Human Societies." Studies in Animal and Human Behaviour, Volume II (Harvard University Press, 2014, ISBN 978-0674430402).

- â The point is already made by Hume, but see Mary Mothersill, "Beauty and the Criticâs Judgment," in Peter Kivy (ed.), The Blackwell Guide to Aesthetics (Malden, MA: Blackwell Pub., 2004, ISBN 0631221301).

- â Virginia I. Lohr, Benefits of Nature: What We Are Learning about Why People Respond to Nature Journal of Physiological Anthropology 26(2) (2007): 83-85. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- â 9.0 9.1 Clement Greenberg, "On Modernist Painting," in David Goldblatt and Lee B. Brown (eds.), Aesthetics: A Reader in Philosophy of Arts (3rd Edition) (Pearson Higher Education, 2010, ISBN 978-0205017034).

- â Denis Dutton, Aesthetic Universals, summarized by Steven Pinker in The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature (Penguin, 2003, ISBN 0142003344).

- â Stephen Davies, Definitions of Art (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1991, ISBN 0801425689)

- â Noel Carroll, Theories of Art Today (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 2000, ISBN 0299163504).

- â David Novitz, The Boundaries of Art (Lisa Loucks Christenson Publishing, LLC, 2003, ISBN 978-1877275241).

- â Tristan Tzara, Sept Manifestes Dada (Pauvert, 1978, ISBN 978-2720201318).

- â Arthur Danto, "Kalliphobia in Contemporary Art" Art Journal 63(2) (Summer 2004): 24-35.

- â Jean-François Lyotard, "What is Postmodernism?" The Postmodern Condition (University Of Minnesota Press, 1984, ISBN 978-0816611737).

- â David Barnhill, East Asian Aesthetics and Nature (ERN), November 21, 2010. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- â Susan M. Vogel, Elements of the African Aesthetic University of Virginia. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bender, John and Gene Blocker. Contemporary Philosophy of Art: Readings in Analytic Aesthetics, 1993.

- Botton, Alain de. The Architecture of Happiness, New York: Pantheon, 2006. ISBN 0375424431

- Carroll, Noel. Theories of Art Today, Madison : University of Wisconsin Press, 2000. ISBN 0299163504

- Dallas, E. S. The Gay Science - in 2 volumes, on the aesthetics of poetry, published in 1866.

- Danto, Arthur C. After the End of Art: Contemporary Art and the Pale of History, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1997. ISBN 0691011737

- Danto, Arthur C. The Abuse of Beauty: Aesthetics and the Concept of Art. Chicago: Open Court, 2003. ISBN 0812695399

- Davies, Stephen. Definitions of Art, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1991. ISBN 0801425689

- Goldblatt, David, and Lee B. Brown (eds.). Aesthetics: A Reader in Philosophy of Arts (3rd Edition). Pearson Higher Education, 2010. ISBN 978-0205017034

- Hatcher, Evelyn. ed. Art as Culture: An Introduction to the Anthropology of Art, Westport, CT: Bergin & Garvey, 1999. ISBN 0897896289

- Hofmann, Hans, Sara T. Weeks, and Bartlett H. Hayes. Search for the Real, And Other Essays. Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 1967.

- Hume, David. Essays: Moral, Political, and Literary. Liberty Fund Inc., 1985. ISBN 978-0865970564

- Kant, Immanuel, J.H. Bernard (transl.). Critique of Judgement. Franklin Classics, 2018. ISBN 978-0342995394

- Kent, A. J. "Aesthetics: A Lost Cause in Cartographic Theory?" The Cartographic Journal, 42/2 (2005): 182-8.

- Kivy, Peter (ed.). The Blackwell Guide to Aesthetics. Malden, MA: Blackwell Pub., 2004. ISBN 0631221301

- Korsmeyer, Carolyn (ed.). Aesthetics: The Big Questions, Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers, 1998. ISBN 0631205934

- Lorenz, Konrad. Studies in Animal and Human Behaviour, Volume II. Harvard University Press, 2014. ISBN 978-0674430402

- Lyotard, Jean-François. The Postmodern Condition. University Of Minnesota Press, 1984. ISBN 978-0816611737

- Novitz, David. The Boundaries of Art. Lisa Loucks Christenson Publishing, LLC, 2003. ISBN 978-1877275241

- Pinker, Steven. The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature. Penguin, 2003. ISBN 0142003344

- Santayana, George. The Sense of Beauty. Being the Outlines of Aesthetic Theory. [1896] New York: Modern Library, 1955.

- Schiller,Friedrich. On the Aesthetic Education of Man, [1795], Dover Publications, 2004.

- Tatarkiewicz, WĆadysĆaw. History of Aesthetics, 3 vols.:1â2, (1970); 3, (1974), The Hague: Mouton.

- Tatarkiewicz, Wladyslaw. A History of Six Ideas: An Essay in Aesthetics, translated from the Polish by Christopher Kasparek, The Hague; Boston: Nijhoff; Hingham, MA: distribution for the U.S. and Canada, Kluwer Boston, 1980. ISBN 9024722330

- Tolstoy, Leo. What Is Art? translated from the Russian by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhansky, London: Penguin, 1995. ISBN 0140446427

- Tzara, Tristan. Sept Manifestes Dada. Pauvert, 1978. ISBN 978-2720201318

- Vogel, Susan Mullin. African Aesthetics. Museum for African Art, 1986. ISBN 978-0961458720

- Whitehead, John. Grasping for the Wind: The Search for Meaning in the 20th Century, Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2001. ISBN 0310232740

External links

All links retrieved June 16, 2023.

- Aesthetics Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Aesthetics. A number of articles on Aesthetics at the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- How Form Functions: On Esthetics and Gestalt Theory.

- Sardo: Theatrical Costume.

- Hackers and Painters.

General philosophy sources

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Paideia Project Online.

- Project Gutenberg.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.