Gu Kaizhi

Gu Kaizhi (Traditional Chinese: 顧愷之; Simplified Chinese: 顾恺之; Hanyu Pinyin: Gù Kǎizhī; Wade-Giles: Ku K'ai-chih) (c. 344 - 406), a celebrated painter of ancient China, is regarded as the founder of traditional Chinese painting. He is best known for his portraits and paintings of human figures, and for his poetry and calligraphy. Although historical records mention more than seventy works of art attributed to him, only copies of three of his handscrolls are extant; Admonitions of the Instructress to the Palace Ladies, Nymph of the Luo River, and Wise and Benevolent Women. He wrote three books about painting theory: On Painting (画论), Introduction of Famous Paintings of Wei and Jin Dynasties (魏晋胜流画赞), and Painting Yuntai Mountain (画云台山记).

In his own time, Gu Kaizhi was said to have painted things "like no one has ever seen before." Gu Kaizhi emphasized details that revealed the characteristics of the figures he drew and paid particular attention to eyes in portrait painting. He was critically renowned for his ability to "describe the spirit through the form" of his subjects. The lines in his painting are like endless silk threads, numerous, detailed, and lifelike. His Graphic Theory later became a basic theory for traditional Chinese painting.

Background

During the 300-years of the Three Kingdoms Period (220-280), the Jin Dynasty (265-420), and the Northern and Southern Dynasties (420-581), Chinese painting experienced important developments. In spite of numerous wars and political instability, there was an active intellectual life which provided a great impetus to artistic development. Grotto murals, tomb paintings, stone carvings, brick carvings, and lacquer paintings were produced, and a number of gifted artists emerged in Chinese calligraphy and painting. Certain theories of painting, such as the Graphic Theory and the Six Rule Theory, which form the theoretical basis for present-day Chinese painting, were also elaborated during this time. Gu Kaizhi, known as the founder of traditional Chinese painting, and his scroll paintings, represented the painting style of the period.

Life

According to historical records, Gu Kaizhi (顧愷之; 顾恺之; Ku K'ai-chih) was born ca. 344 into an official family in Wuxi (無錫), Jiangsu (江蘇) province and first painted at Nanjing (南京) in 364. In 366 he became a government officer (Da Sima Canjun, 大司马参军) , and toured many beautiful places. Later he was promoted to royal officer (Sanji Changshi, 散骑常侍). He was also a talented poet and calligrapher. He wrote three books about painting theory: On Painting (画论), Introduction of Famous Paintings of Wei and Jin Dynasties (魏晋胜流画赞), and Painting Yuntai Mountain (画云台山记). He wrote, "In figure paintings the clothes and the appearances were not very important. The eyes were the spirit and the decisive factor." He was known for his sense of humor, and was also a skillful poet and essayist. Chinese art history abounds in anecdotes about him. According to historical records, Gu created more than seventy paintings based on historical stories, Buddhas, human figures, birds, animals, mountains, and rivers. Gu's art is known today through copies of three silk handscroll paintings attributed to him; these are the earliest examples of scroll paintings. Gu's paintings were similar in style to the Dunhuang murals, and strongly influenced on later traditional Chinese paintings.

In his own time, Gu Kaizhi was said to have painted things "like no one has ever seen before" and was critically renowned for his ability to "describe the spirit through the form" (Chinese: yi xing xie shen) of his subjects, using a gossamer-like ink-outline. His paintings exhibit extraordinary spirit and charm. His skill was said to be unrivaled. Ideas were expressed in brush strokes. The lines in his painting are like endless silk threads, numerous, detailed, and lifelike. The free flow of lines in painting came to represent the fluid emotions in people.

Theory of art

Gu’s theoretical works, which included Painting Thesis and Notes on Painting the Yuntai Mountain, became classic texts for Chinese artists and scholars. He paid considerable attention to demonstrating the spirit of human figures through vivid expressions. His Graphic Theory later became a basic theory for traditional Chinese painting.

Admonitions of the Instructress to the Palace Ladies

Admonitions of the Instructress to the Palace Ladies (Chinese: Nushi zhen tujuan), probably a Tang dynasty copy, illustrates nine stories from a political satire about Empress Jia (賈后) written by Zhang Hua (张华 ca. 232-302). Beginning in the eighth century, many collectors and emperors left seals, poems, and comments on the scroll. The Admonitions scroll was kept in the emperor's treasure stores until they were looted by the British army in the Boxer Uprising in 1900. Now it is in the British Museum collection, missing the first two scenes. Restoration specialists working on the scroll used the wrong materials and caused it to become brittle, so it can only be displayed flat. The original copy is a horizontal handscroll, painted by ink and color on silk.

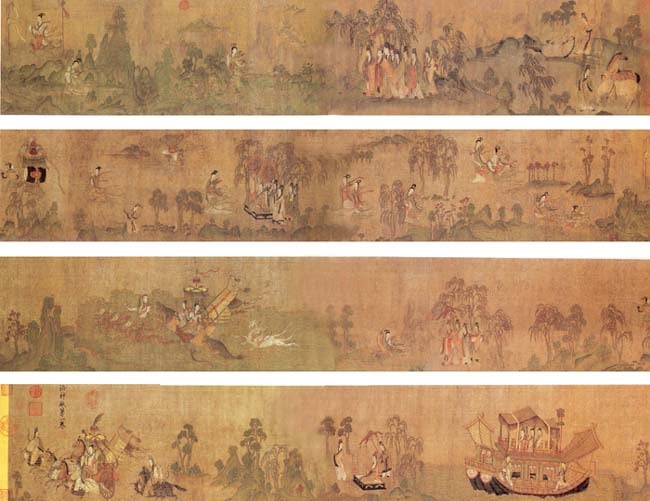

Nymph of the Luo River (洛神赋)

Nymph of the Luo River survives in three copies dating to the Song dynasty. It illustrates a poem written by Cao Zhi (曹植 192-232). One copy is held by the Palace Museum of Beijing; another is at the Freer Gallery in Washington, D.C. The third was brought to Manchu by the last emperor Pu Yi (溥仪 1906-1967) while he was the puppet emperor of Manchukuo under Japanese rule. When the Japanese surrendered in 1945, the painting disappeared. After ten years the Liaoning provincial museum recovered it.

The theme of the Luoshen Appraisal Painting was drawn from the article, Luoshen Appraisal, written by Cao Zhi, son of the Wei Emperor Cao Cao. It depicts the meeting of Cao Zhi and Goddess Luoshen at the Luoshui River. The picture vividly portrays their moods when they first met each other and when they were finally forced to separate. Gu emphasized the expressions of the figures; the stones, mountains and trees in the picture were for ornamental purposes.

Wise and Benevolent Women

Little scholarship on this painting seems to exist in English.

Poems

- The spring water fills the lakes everywhere.

- The summer clouds resemble the peaks.

- The autumn moon is shining brightly.

- The winter mountain highlights the pine tree.

The famous 20-word poem "Four Seasons," by Gu Kaizhi describes the natural beauty of the changing seasons. The four lines evoke four beautiful images. His literary talent is often compared to that of Ji Kang, and his calligraphy, with that of Wang Xizhi. His greatest achievement, however, was painting.

Gu Kaizhi was honest, sincere, determined, and impassioned. Grieving for his benefactor, he wrote:

Your unexpected death is like the collapse of the mountain, the exhaustion of the sea, while I am like a fish and a bird. How am I going to survive? My crying is like thunder destroying mountains and my tears are like rivers rushing into the sea.[1]

Anecdotes

Once a temple was being planned for Jiankang, capital of the Eastern Jin Dynasty (present-day Nanjing), but the monks and the abbot could not collect enough money to pay for its construction. When the Wa Guan Temple had been completed, a celebration was held at which a famous Master was invited to strike the bell in order to raise funds. Officials and wealthy patrons, however, donated only 100,000 yuan. Gu kaizhi, as soon as he stepped inside the temple, wrote a pledge of 1 million yuan in the record book. The abbot did not believe him, and the people were aghast, thinking that he was boasting. Gu Kaizhi began to paint a picture of "Weimo" (a Buddha at the time of Sakyamuni, meaning purity) on a wall. For three consecutive days, thousands of people crowded around to see the young man painting the Buddha. He refused to draw the eyes until the last day, when the spectators were requested to donate 100,000 yuan. On the final day, crowds of people thronged to the temple. Gu Kaizhi cleansed himself, lit the incense, prayed silently, and made two strokes in the right position. Suddenly, the "Weimo" on the wall seemed to come to life, and his eyes shone with kindness inside the temple. The viewers cheered and applauded, and began to make generous donations. Soon several million yuan was collected. The ceremony of "painting the eyes," now practiced in Japan, was passed down from this period.[2]

Gu Kaizhi emphasized details that revealed the characteristics of the figures he drew. Once he was asked to paint the portrait of a man called Pei Kai, who had three long fine hairs on his face that had been ignored by other painters. Gu paid great attention to the three hairs, and Pei was very satisfied. Another time, Gu portrayed the man Xie Kun standing in the midst of mountains and rocks, explaining that Xie loved to travel to see beautiful mountains and rivers.[3]

Gu Kaizhi paid particular attention to eyes in portrait painting, whether human beings, Gods, or Buddhas, saying, "Spirit, charm and life are all shown in eyes." Once he painted Ruan Ji and Ji Kang (the sages of the Bamboo Forest) on a fan but did not draw in their eyes. When asked why, he replied humorously, "I could never paint their eyes, otherwise they would be able to speak!"

Nihonga meets Gu Kaizhi: a Japanese copy of a Chinese painting in the British Museum.

In 1923, Kobayashi Kokei (1883-1957) and Maeda Seison (1885-1977), two masters of Japanese neotraditional painting, Nihonga, devoted enormous effort to collaborating on a copy of the Admonitions of the Court Instructress (Japanese: Joshi shin zukan no mosha; Figs. 2-8, 14, 19) at the British Museum. Both artists recognized that they had been given the opportunity to copy one of the most celebrated Chinese paintings in Europe, which was also one of the oldest Chinese paintings extant and a long-revered masterpiece attributed to Gu Kaizhi. When the two painters returned to Japan in 1923, they had not only embraced Western classicism (yoga, or "foreign painting" techniques) but also, through their work on the Admonitions, rediscovered some of the basics of East Asian painting: Modulation of line, harmony of color wash, and concern with the immanence of a subject. Both men went on to receive the highest national honors for their artistic achievements. Copy of the Admonitions of the Court Instructress is now in the collection of Tohoku University Library in Sendai in northeastern Japan.[4]

Notes

- ↑ Xabusiness.com, Gu Kaizhi—one of greatest artist of ancient China.

- ↑ Xabusiness.com, Gu Kaizhi. Retrieved October 20, 2007.

- ↑ SeeChina.com, Gu Kaizhi and the Beginning of Scroll Painting. Retrieved October 20, 2007.

- ↑ HighBeam Research Inc., Nihonga meets Gu Kaizhi. Retrieved October 20, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- McCausland, Shane and Kaizhi Gu. First Masterpiece of Chinese Painting: The Admonitions Scroll. New York: George Braziller, Publishers, 2003. ISBN 080761517X

- Fang, Xuanling and Shih-hsiang Chʻên. Biography of Ku Kʻai-chih. Chinese Dynastic Histories Translations, no. 2. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1961.

- Huijzer, Wieteke. The Admonitions' Heritage: The Admonitions Scroll's Extensive Influence on Later Didactic Paintings for Chinese Women. [S.l: s.n.]. 2005.

- Li, Xianglin. Gu Kaizhi. Lang lang shu fang. Beijing: Zhongguo ren min da xue chu ban she, 2004. ISBN 7300051626

- Mather, Richard B., et. al. Studies in Early Medieval Chinese Literature and Cultural History: In Honor of Richard B. Provo, Utah: Tʻang Studies Society, 2003. ISBN 0972925503

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.