Drama

| Literature |

|---|

| Major forms |

| Epic ⢠Romance ⢠Novel ⢠Novella ⢠Tragedy ⢠Comedy ⢠Drama ⢠Folklore |

| Media |

| Play ⢠Book |

| Techniques |

| Prose ⢠Poetry |

| Discussion |

| Criticism ⢠Theory |

The term drama comes from a Greek word meaning "action" (Classical Greek: δÏάμα, dráma), which is derived from "to do" (Classical Greek: δÏάÏ, dráÅ). The enactment of drama in theater, performed by actors on a stage before an audience, is a widely used art form that is found in virtually all cultures.

The two masks associated with drama represent the traditional generic division between comedy and tragedy. They are symbols of the ancient Greek Muses, Thalia and Melpomene. Thalia was the Muse of comedy (the laughing face), while Melpomene was the Muse of tragedy (the weeping face).

The use of "drama" in the narrow sense to designate a specific type of play dates from Nineteenth-century theatre. Drama in this sense refers to a play that is neither a comedy nor a tragedy, such as Ãmile Zola's Thérèse Raquin (1873) or Anton Chekhov's Ivanov (1887). It is this narrow sense that the film and television industry and film studies adopted to describe "drama" as a genre within their respective media.

Theories of drama date back to the work of the Ancient Greek philosophers. Plato, in a famous passage in "The Republic," wrote that he would outlaw drama from his ideal state because the actor encouraged citizens to imitate their actions on stage. In his "Poetics," Aristotle famously argued that tragedy leads to catharsis, allowing the viewer to purge unwanted emotional affect, and serving the greater social good.

History of Western drama

| History of Western theatre |

|---|

| Greek ⢠Roman ⢠Medieval ⢠Commedia dell'arte ⢠English Early Modern ⢠Spanish Golden Age ⢠Neoclassical ⢠Restoration ⢠Augustan ⢠Weimar ⢠Romanticism ⢠Melodrama ⢠Naturalism ⢠Realism ⢠Modernism ⢠Postmodern 19th century ⢠20th century |

Classical Athenian drama

| Classical Athenian drama |

|---|

| Tragedy ⢠Comedy ⢠Satyr play Aeschylus ⢠Sophocles ⢠Euripides ⢠Aristophanes ⢠Menander |

Western drama originates in classical Greece. The theatrical culture of the city-state of Athens produced three genres of drama: tragedy, comedy, and the satyr play. Their origins remain obscure, though by the fifth century B.C.E. they were institutionalized in competitions held as part of festivities celebrating the god Dionysus.[1] Historians know the names of many ancient Greek dramatists, not least Thespis, who is credited with the innovation of an actor ("hypokrites") who speaks (rather than sings) and impersonates a character (rather than speaking in his own person), while interacting with the chorus and its leader ("coryphaeus"), who were a traditional part of the performance of non-dramatic poetry (dithyrambic, lyric and epic).[2] Only a small fraction of the work of five dramatists, however, has survived to this day: we have a small number of complete texts by the tragedians Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides, and the comic writers Aristophanes and, from the late fourth century, Menander.[3] Aeschylus' historical tragedy The Persians is the oldest surviving drama, although when it won first prize at the City Dionysia competition in 472 B.C.E., he had been writing plays for more than 25 years.[4] The competition ("agon") for tragedies may have begun as early as 534 B.C.E.; official records ("didaskaliai") begin from 501 B.C.E., when the satyr play was introduced.[5] Tragic dramatists were required to present a tetralogy of plays (though the individual works were not necessarily connected by story or theme), which usually consisted of three tragedies and one satyr play (though exceptions were made, as with Euripides' Alcestis in 438 B.C.E.). Comedy was officially recognized with a prize in the competition from 487-486 B.C.E. Five comic dramatists competed at the City Dionysia (though during the Peloponnesian War this may have been reduced to three), each offering a single comedy.[6] Ancient Greek comedy is traditionally divided between "old comedy" (5th century B.C.E.), "middle comedy" (fourth century B.C.E.) and "new comedy" (late fourth century to second B.C.E.).[7]

The Tenants of Classicism

The expression classicism as it applies to drama implies notions of order, clarity, moral purpose and good taste. Many of these notions are directly inspired by the works of Aristotle and Horace and by classical Greek and Roman masterpieces.

According to the tenants of classicism, a play should follow the Three Unities:

- Unity of place : the setting should not change. In practice, this lead to the frequent "Castle, interior." Battles take place off stage.

- Unity of time: ideally the entire play should take place in 24 hours.

- Unity of action: there should be one central story and all secondary plots should be linked to it.

Although based on classical examples, the unities of place and time were seen as essential for the spectator's complete absorption into the dramatic action; wildly dispersed settings or the break in time was considered detrimental to creating the theatrical illusion. Sometimes grouped with the unity of action is the notion that no character should appear unexpectedly late in the drama.

Roman drama

Following the expansion of the Roman Republic (509-27 B.C.E.) into several Greek territories between 270-240 B.C.E., Rome encountered Greek drama.[8] From the later years of the republic and by means of the Roman Empire (27 B.C.E.-476 C.E.), theater spread west across Europe, around the Mediterranean and reached England; Roman theater was more varied, extensive and sophisticated than that of any culture before it.[9] While Greek drama continued to be performed throughout the Roman period, the year 240 B.C.E. marks the beginning of regular Roman drama.[10] From the beginning of the empire, however, interest in full-length drama declined in favor of a broader variety of theatrical entertainments.[11] The first important works of Roman literature were the tragedies and comedies that Livius Andronicus wrote from 240 B.C.E.[12] Five years later, Gnaeus Naevius also began to write drama.[12] No plays from either writer have survived. While both dramatists composed in both genres, Andronicus was most appreciated for his tragedies and Naevius for his comedies; their successors tended to specialize in one or the other, which led to a separation of the subsequent development of each type of drama.[12] By the beginning of the second century B.C.E., drama was firmly established in Rome and a guild of writers (collegium poetarum) had been formed.[13] The Roman comedies that have survived are all fabula palliata (comedies based on Greek subjects) and come from two dramatists: Titus Maccius Plautus (Plautus) and Publius Terentius Afer (Terence).[14] In re-working the Greek originals, the Roman comic dramatists abolished the role of the chorus in dividing the drama into episodes and introduced musical accompaniment to its dialogue (between one-third of the dialogue in the comedies of Plautus and two-thirds in those of Terence).[15] The action of all scenes is set in the exterior location of a street and its complications often follow from eavesdropping.[15] Plautus, the more popular of the two, wrote between 205-184 B.C.E. and 20 of his comedies survive, of which his farces are best known; he was admired for the wit of his dialogue and his use of a variety of poetic meters.[16] All of the six comedies that Terence wrote between 166-160 B.C.E. have survived; the complexity of his plots, in which he often combined several Greek originals, was sometimes denounced, but his double-plots enabled a sophisticated presentation of contrasting human behavior.[16] No early Roman tragedy survives, though it was highly-regarded in its day; historians know of three early tragediansâQuintus Ennius, Marcus Pacuvius and Lucius Accius.[15] From the time of the empire, the work of two tragedians survivesâone is an unknown author, while the other is the Stoic philosopher Seneca.[17] Nine of Seneca's tragedies survive, all of which are fabula crepidata (tragedies adapted from Greek originals); his Phaedra, for example, was based on Euripides' Hippolytus.[18] Historians do not know who wrote the only extant example of the fabula praetexta (tragedies based on Roman subjects), Octavia, but in former times it was mistakenly attributed to Seneca due to his appearance as a character in the tragedy.[17]

Medieval and Renaissance drama

In the Middle Ages, drama in the vernacular languages of Europe may have emerged from religious enactments of the liturgy. Mystery plays were presented on the porch of the cathedrals or by strolling players on feast days.

Renaissance theater derived from several medieval theater traditions, such as the mystery plays that formed a part of religious festivals in England and other parts of Europe during the Middle Ages. The mystery plays were complex retellings of legends based on biblical themes, originally performed in churches but later becoming more linked to the secular celebrations that grew up around religious festivals. Other sources include the morality plays that evolved out of the mysteries, and the "University drama" that attempted to recreate Greek tragedy. The Italian tradition of Commedia dell'arte as well as the elaborate masques frequently presented at court came to play roles in the shaping of public theater. Miracle and mystery plays, along with moralities and interludes, later evolved into more elaborate forms of drama, such as was seen on the Elizabethan stages.

Elizabethan and Jacobean

One of the great flowerings of drama in England occurred in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Many of these plays were written in verse, particularly iambic pentameter. In addition to Shakespeare, such authors as Christopher Marlowe, Thomas Middleton, and Ben Jonson were prominent playwrights during this period. As in the medieval period, historical plays celebrated the lives of past kings, enhancing the image of the Tudor monarchy. Authors of this period drew some of their storylines from Greek mythology and Roman mythology or from the plays of eminent Roman playwrights such as Plautus and Terence.

William Shakespeare

Shakespeare's plays are considered by many to be the pinnacle of the dramatic arts. His early plays were mainly comedies and histories, genres he raised to the peak of sophistication by the end of the sixteenth century. In his following phase he wrote mainly tragedies, including Hamlet, King Lear, Macbeth, and Othello. The plays are often regarded as the summit of Shakespeare's art and among the greatest tragedies ever written. In 1623, two of his former theatrical colleagues published the First Folio, a collected edition of his dramatic works that included all but two of the plays now recognized as Shakespeare's.

Shakespeare's canon has achieved a unique standing in Western literature, amounting to a humanistic scripture. His insight in human character and motivation and his luminous, boundary-defying diction have influenced writers for centuries. Some of the more notable authors and poets so influenced are Samuel Taylor Coleridge, John Keats, Charles Dickens, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Herman Melville, and William Faulkner. According to Harold Bloom, Shakespeare "has been universally judged to be a more adequate representer of the universe of fact than anyone else, before or since."[19]

Seventeenth century French Neo-classicism

While the Puritans were shutting down theaters in England, one of the greatest flowerings of drama was taking place in France. By the 1660s, neo-classicism had emerged as the dominant trend in French theater. French neo-classicism represented an updated version of Greek and Roman classical theater. The key theoretical work on theater from this period was François Hedelin, abbé d'Aubignac's "Pratique du théâtre" (1657), and the dictates of this work reveal to what degree "French classicism" was willing to modify the rules of classical tragedy to maintain the unities and decorum (d'Aubignac for example saw the tragedies of Oedipus and Antigone as unsuitable for the contemporary stage).

Although Pierre Corneille continued to produce tragedies to the end of his life, the works of Jean Racine from the late 1660s on totally eclipsed the late plays of the elder dramatist. Racine's tragediesâinspired by Greek myths, Euripides, Sophocles and Senecaâcondensed their plot into a tight set of passionate and duty-bound conflicts between a small group of noble characters, and concentrated on these characters' conflicts and the geometry of their unfulfilled desires and hatreds. Racine's poetic skill was in the representation of pathos and amorous passion (like Phèdre's love for her stepson) and his impact was such that emotional crisis would be the dominant mode of tragedy to the end of the century. Racine's two late plays ("Esther" and "Athalie") opened new doors to biblical subject matter and to the use of theater in the education of young women.

Tragedy in the last two decades of the century and the first years of the eighteenth century was dominated by productions of classics from Pierre Corneille and Racine, but on the whole the public's enthusiasm for tragedy had greatly diminished: theatrical tragedy paled beside the dark economic and demographic problems at the end of the century and the "comedy of manners" (see below) had incorporated many of the moral goals of tragedy. Other later century tragedians include: Claude Boyer, Michel Le Clerc, Jacques Pradon, Jean Galbert de Campistron, Jean de la Chapelle, Antoine d'Aubigny de la Fosse, l'abbé Charles-Claude Geneste, Prosper Jolyot de Crébillon.

Comedy in the second half of the century was dominated by Molière. A veteran actor, master of farce, slapstick, the Italian and Spanish theater (see above), and "regular" theater modeled on Plautus and Terence, Molière's output was large and varied. He is credited with giving the French "comedy of manners" ("comédie de mÅurs") and the "comedy of character ("comédie de caractère") their modern form. His hilarious satires of avaricious fathers, "précieuses," social parvenues, doctors and pompous literary types were extremely successful, but his comedies on religious hypocrisy ("Tartuffe") and libertinage ("Don Juan") brought him much criticism from the church, and "Tartuffe" was only performed through the intervention of the king. Many of Molière's comedies, like "Tartuffe," "Don Juan" and the "Le Misanthrope" could veer between farce and the darkest of dramas, and the endings of "Don Juan" and the "Misanthrope" are far from being purely comic.

Comedy to the end of the century would continue on the paths traced by Molière: the satire of contemporary morals and manners and the "regular" comedy would dominate, and the last great "comedy" of Louis XIV's reign, Alain-René Lesage's "Turcaret," is an immensely dark play in which almost no character shows redeeming traits.

Realism and Naturalism

In the nineteenth century, Realism became the dominant trend in modern drama largely through the works of the Norwegian playwright, Henrik Ibsen and the Russian writer, Anton Chekhov. Realism first achieved popularity in the novel, but Ivan Turgenev and other playwright began to experiment with it in their dramas in the late nineteenth century. Ibsen's work helped to rewrite the rules of drama and were further developed by Chekhov, remaining an important part of the theater to this day. From Ibsen forward, drama became more interested in social concerns, challenging assumptions and directly commenting on issues.

Naturalism was a movement in European drama that developed in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. It refers to theater that attempts to create a perfect illusion of reality through a range of dramatic and theatrical strategies: detailed, three-dimensional settings (which bring Darwinian understandings of the determining role of the environment into the staging of human drama); everyday speech forms (prose over poetry); a secular world-view (no ghosts, spirits or gods intervening in the human action); an exclusive focus on subjects that were contemporary and indigenous (no exotic, otherworldly or fantastic locales, nor historical or mythic time-periods); an extension of the social range of characters portrayed (away from the aristocrats of classical drama, towards bourgeois and eventually working-class protagonists); and a style of acting that attempts to recreate the impression of reality.

Modern and contemporary theater

Inspired by the changes in the literary and art world in the twentieth century, in which numerous new artistic movements like Cubism, Surrealism, and Futurism. A number of theatrical movements arose which rejected the nineteenth century realist model, choosing instead to play with the language and elements of dramatic convention which had previously been dominant. These included the Brechtian Epic theater, Artaud's Theater of Cruelty and the so-called Theatre of the Absurd.

Epic theater

Epic theater arose in the early to mid-twentieth century from the theories and practice of a number of theatre practitioners, including Erwin Piscator, Vladimir Mayakovsky, Vsevolod Meyerhold and, most famously, Bertolt Brecht. Epic theater rejects the core tenants of Realism and Naturalism, asserting that the purpose of a play, more than entertainment or the imitation of reality, is to present ideas and invites the audience to make judgments on them. Characters are not intended to mimic real people, but to represent opposing sides of an argument, archetypes, or stereotypes. The audience should always be aware that it is watching a play, and should remain at an emotional distance from the action; Brecht described this ideal as the Verfremdungseffektâvariously translated as "alienation effect," "defamiliarization effect," or "estrangement effect." It is the opposite of the suspension of disbelief:

"It is most important that one of the main features of the ordinary theatre should be excluded from [epic theatre]: the engendering of illusion."[21]

Common production techniques in epic theatre include simplified, non-realistic set designs and announcements, or visual captions, that interrupt and summarize the action. Brecht used comedy to distance his audiences from emotional or serious events, and was heavily influenced by musicals and fairground performers, putting music and song in his plays.

Acting in epic theatre requires actors to play characters believably without convincing either the audience or themselves that they are truly the characters.

Epic theater was a reaction against other popular forms of theater, particularly the realistic drama pioneered by Constantin Stanislavski. Like Stanislavski, Brecht disliked the shallow spectacle, manipulative plots, and heightened emotion of melodrama; but where Stanislavski attempted to engender real human behavior in acting through the techniques of Stanislavski's system, and through the actors to engage the audience totally into the world of the play, Brecht saw Stanislavski's methodology as producing audience escapism.

Theatre of Cruelty

Brecht's own social and political focus departed also from surrealism and the Theatre of Cruelty, as developed in the writings and dramaturgy of Antonin Artaud, who sought to affect audiences viscerally, psychologically, physically, and irrationally. Artaud had a pessimistic view of the world, but he believed that theater could affect change. His approach tried to remove the audience from the everyday, and use symbolic objects to work with the emotions and soul of the audience. The goal was to attack the audience's senses through an array of technical methods and acting so that they would be brought out of their desensitization and have to confront themselves, through the use of the grotesque, the ugly, and pain.

Theatre of the Absurd

Theatre of the Absurd is a designation for particular plays written by a number of primarily European playwrights in the late 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s, as well as to the style of theatre which has evolved from their work.

The term was coined by the critic Martin Esslin based on Albert Camus' philosophy that life is inherently without meaning, as illustrated in his work The Myth of Sisyphus. Though the term is applied to a wide range of plays, some characteristics coincide in many of the plays: broad comedy, often similar to Vaudeville, mixed with horrific or tragic images; characters caught in hopeless situations forced to do repetitive or meaningless actions; dialogue full of clichés, wordplay, and nonsense; plots that are cyclical or absurdly expansive; either a parody or dismissal of realism and the concept of the "well-made play." In the first (1961) edition, Esslin presented the four defining playwrights of the movement as Samuel Beckett, Arthur Adamov, Eugene Ionesco, and Jean Genet, and in subsequent editions he added a fifth playwright, Harold Pinter - although each of these writers has unique preoccupations and techniques that go beyond the term "absurd."[22]Other writers whom Esslin associated with this group include Tom Stoppard, Friedrich Dürrenmatt, Fernando Arrabal, Edward Albee, and Jean Tardieu.

Other Cultural Forms

Indian

Indian theater began with the Rigvedic dialogue hymns during the Vedic period, and Sanskrit drama was established as a distinct art form in the last few centuries B.C.E. The earliest theoretical account of Indian drama is Bharata Muni's Natya Shastra that may be as old as the 3rd century B.C.E. Drama was patronized by the kings as well as village assemblies. Famous early playwrights include Bhasa and Kalidasa. During the Middle Ages, the Indian subcontinent was invaded a number of times. This played a major role in shaping of Indian culture and heritage. Medieval India experienced a grand fusion with the invaders from the Middle East and Central Asia. British India, as a colony of the British Empire, used theater as one of its instruments in protest. To resist, the British Government had to impose "Dramatic Performance Act" in 1876. From the last half of the 19th century, theaters in India experienced a boost in numbers and practice. The Ramayana and the Mahabharata stories have often been used for plots in Indian drama and this practice continues today.

Chinese

Chinese theater has a long and complex history. Today it is often called Chinese opera although this normally refers specifically to the popular form known as Beijing Opera, a form of Chinese opera which arose in the late eighteenth century and became fully developed and recognized by the mid-nineteenth century.[23] The form was extremely popular in the Qing Dynasty court and has come to be regarded as one of the cultural treasures of China. Major performance troupes are based in Beijing and Tianjin in the north, and Shanghai in the south. The art form is also enjoyed in Taiwan, and has spread to other countries such as the United States and Japan.

Beijing opera features four main types of performers; performing troupes often have several of each variety, as well as numerous secondary and tertiary performers. With their elaborate and colorful costumes, performers are the only focal points on Beijing opera's characteristically sparse stage. They utilize the skills of speech, song, dance, and combat in movements that are symbolic and suggestive, rather than realistic. The skill of performers is evaluated according to the beauty of their movements. Performers also adhere to a variety of stylistic conventions that help audiences navigate the plot of the production.[24]The layers of meaning within each movement must be expressed in time to music. The music of Beijing opera can be divided into the Xipi and Erhuang styles. Melodies include arias, fixed-tune melodies, and percussion patterns. The repertoire of Beijing opera includes over 1400 works, which are based on Chinese history, folklore, and, increasingly, contemporary life.[25]

Japanese

Japanese NÅ drama is a serious dramatic form that combines drama, music, and dance into a complete aesthetic performance experience. It developed in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries and has its own musical instruments and performance techniques, which were often handed down from father to son. The performers were generally male (for both male and female roles), although female amateurs also perform NÅ dramas. NÅ drama was supported by the government, and particularly the military, with many military commanders having their own troupes and sometimes performing themselves. It is still performed in Japan today.

Noh dramas are highly choreographed and stylized, and include poetry, chanting and slow, elegant dances accompanied by flute and drum music. The stage is almost bare, and the actors use props and wear elaborate costumes. The main character sometimes wears a Noh mask. Noh plays are taken from the literature and history of the Heian period and are intended to illustrate the principles of Buddhism.

KyÅgen is the comic counterpart to Noh drama. It concentrates more on dialogue and less on music, although NÅ instrumentalists sometimes appear also in KyÅgen. It developed alongside noh, was performed along with noh as an intermission of sorts between noh acts, and retains close links to noh in the modern day; therefore, it is sometimes designated noh-kyÅgen. However, its content is not at all similar to the formal, symbolic, and solemn noh theater; kyÅgen is a comical form, and its primary goal is to make its audience laugh.

Forms of Drama

Opera

Western opera is a dramatic art form, which arose during the Renaissance in an attempt to revive the classical Greek drama tradition in which both music and theatre were combined. Being strongly intertwined with western classical music, the opera has undergone enormous changes in the past four centuries and it is an important form of theatre until this day. Noteworthy is the huge influence of the German nineteenth century composer Richard Wagner on the opera tradition. In his view, there was no proper balance between music and theatre in the operas of his time, because the music seemed to be more important than the dramatic aspects in these works. To restore the connection with the traditional Greek drama, he entirely renewed the operatic format, and to emphasize the equally importance of music and drama in these new works, he called them "music dramas".

Chinese opera has seen a more conservative development over a somewhat longer period of time.

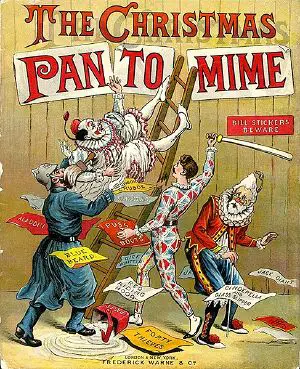

Pantomime

These stories follow in the tradition of fables and folk tales, usually there is a lesson learned, and with some help from the audience the hero/heroine saves the day. This kind of play uses stock characters seen in masque and again commedia del arte, these characters include the villain (doctore), the clown/servant(Arlechino/Harlequin/buttons), the lovers, etc. These plays usually have an emphasis on moral dilemmas, and good always triumphs over evil, this kind of play is also very entertaining, making it a very effective way of reaching many people.

Film and television

In the twentieth century with the creation of the motion picture camera, the potential to film theater productions came into being. From the beginning, film exploited its cinematic potential to capture live action, such as a train coming down the tracks directly at the audience. Scandinavian films were largely shot outdoors in the summer light, using a natural setting. Film soon demonstrated its potential to produce plays in a natural setting as well. It also created new forms of drama, such as the Hitchcockian suspense film, and with the rise of technology, the action film. It also became the medium for science fiction as well. Television became not only a medium for showing films, but also created new forms of drama, especially the "police drama" in which crimes are committed and solved within an hour long format, and the "medical drama" in which life and death dramas were played out in recurring weekly episode. From the 1980s both dramas experimented with ensemble casts, which featured not just a classic hero, but a number of different "lead" actors and blending a number of different story lines simultaneously.

Legacy

Drama is the specific mode of fiction represented in performance.[26] The structure of dramatic texts, unlike other forms of literature, is directly influenced by this collaborative production and collective reception.[27]

Drama is often combined with music and dance: the drama in opera is sung throughout; musicals include spoken dialogue and songs; and some forms of drama have regular musical accompaniment (melodrama and Japanese NÅ, for example).[28] In certain periods of history (the ancient Roman and modern Romantic) dramas have been written to be read rather than performed.[29] In improvisation, the drama does not pre-exist the moment of performance; performers devise a dramatic script spontaneously before an audience. Some forms of improvisation, notably the Commedia dell'arte, improvise on the basis of 'lazzi' or rough outlines of scenic action.[30][31] All forms of improvisation take their cue from their immediate response to one another, their characters' situations (which are sometimes established in advance), and, often, their interaction with the audience. The classic formulations of improvisation in the theatre originated with Joan Littlewood and Keith Johnstone in the UK and Viola Spolin in the USA.[32][33]

Notes

- â Oscar G. Brockett and Franklin J. Hildy, History of the Theatre (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 2003), 13-15.

- â Martin Banham (ed.), The Cambridge Guide to Theatre (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998, ISBN 0521434378), 441-444).

- â The theory that Prometheus Bound was not written by Aeschylus would bring this number to six dramatists whose work survives.

- â Banham, 8; Brockett and Hildy, 15-16

- â Brockett and Hildy, 13, 15; Banham, 442.

- â Brockett and Hildy, 18; Banham, 444-445.

- â Banham, 444-445.

- â Brockett and Hildy, 43.

- â Brockett and Hildy, 36, 47.

- â Brockett and Hildy, 43.

- â Brockett and Hildy, 46-47.

- â 12.0 12.1 12.2 Brockett and Hildy, 47.

- â Brockett and Hildy, 47-48.

- â Brockett and Hildy, 48-49.

- â 15.0 15.1 15.2 Brockett and Hildy, 49.

- â 16.0 16.1 Brockett and Hildy, 48.

- â 17.0 17.1 Brockett and Hildy, 50.

- â Brockett and Hildy, 49-50.

- â Harold Bloom, Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human (New York: Riverhead, 1998, ISBN 1573221201).

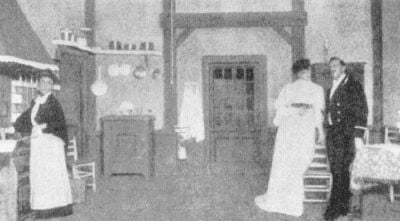

- â Sacha Sjöström (left) as Kristin, Manda Björling as Miss Julie, and August Falck as Jean.

- â Bertolt Brecht, Brecht on Theatre: The Development of an Aesthetic, edited and translated by John Willett (New York, Hill and Wang, 1964), 122.

- â Martin Esslin, The Theatre of the Absurd (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1961).

- â Joshua S. Goldstein, Drama Kings: Players and Publics in the Re-creation of Peking Opera, 1870â1937 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007, ISBN 0520247523), 3.

- â Elizabeth Wichmann. Listening to Theatre: The Aural Dimension of Beijing Opera (University of Hawaii Press, 1991, ISBN 0824812212), 360.

- â Wichmann, 12â16.

- â Keir Elam, The Semiotics of Theatre and Drama (London and New York: Methuen, 1980, ISBN 0416720609), 98.

- â Manfred Pfister, The Theory and Analysis of Drama Trans. John Halliday (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1977, ISBN 052142383X), 11.

- â Banham, entries for: "opera," "musical theatre, American," "melodrama" and "NÅ."

- â While there is some dispute among theater historians, it is probable that the plays by the Roman Seneca were not intended to be performed. Manfred by Lord Byron is a good example of a "dramatic poem." See the entries on "Seneca" and "Byron (George George)" in Banham (1998).

- â Mel Gordon, Lazzi: The Comic Routines of the Commedia dell'Arte (New York: Performing Arts Journal Publications, 1983, ISBN 0933826699)

- â Pierre Louis Duchartre, The Italian Comedy Unabridged republication. (New York: Dover, 1966, ISBN 0486216799).

- â Keith Johnstone, Impro: Improvisation and the Theatre (London: Methuen, 1981, ISBN 0713687010).

- â Viola Spolin, Improvisation for the Theater (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, (1963) 1999, ISBN 081014008X).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Banham, Martin, ed. The Cambridge Guide to Theatre. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998. ISBN 0521434378

- Bloom, Harold. Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human. New York: Riverhead, 1998. ISBN 1573221201

- Brecht, Bertolt. Brecht on Theatre: The Development of an Aesthetic, edited and translated by John Willett. New York, Hill and Wang, 1964.

- Brockett, Oscar G. and Franklin J. Hildy. History of the Theatre, Ninth edition, International ed. Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 2003. ASIN B001ANP94I

- Duchartre, Pierre Louis. The Italian Comedy. Unabridged republication. New York: Dover, 1966 (original 1929). ISBN 0486216799

- Elam, Keir. The Semiotics of Theatre and Drama. (New Accents Ser.) London and New York: Methuen, 1980. ISBN 0416720609

- Esslin, Martin. The Theatre of the Absurd. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1961.

- Goldstein, Joshua S. Drama Kings: Players and Publics in the Re-creation of Peking Opera, 1870â1937. University of California Press, 2007. ISBN 0520247523

- Gordon, Mel. Lazzi: The Comic Routines of the Commedia dell'Arte. New York: Performing Arts Journal Publications, 1983. ISBN 0933826699

- Johnstone, Keith. Impro: Improvisation and the Theatre, Rev. ed. London: Methuen, 2007. ISBN 0713687010

- Pfister, Manfred. The Theory and Analysis of Drama,.Trans. John Halliday. (European Studies in English Literature) Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988 (original 1977). ISBN 052142383X

- Spolin, Viola. Improvisation for the Theater, Third rev. ed Evanston, Il.: Northwestern University Press, 1999 (original 1967). ISBN 081014008X

- Wichmann, Elizabeth. Listening to Theatre: The Aural Dimension of Beijing Opera. University of Hawaii Press, 1991. ISBN 0824812212

External links

All links retrieved January 30, 2024.

- Illustrated Greek Drama by Janice Siegel, Department of Classics, Hampden-Sydney College, Virginia.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Drama history

- Drama history

- Kyogen history

- Theatre_in_India history

- Theatre_of_France history

- Naturalism_(theatre)Â history

- Epic_theatre history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.