The Maya civilization is a Mesoamerican culture, noted for having the only known fully developed written language of the pre-Columbian Americas, as well as for its spectacular art, monumental architecture, and sophisticated mathematical and astronomical systems. Unfortunately, a public fascination with the morbid has meant that for many people in Europe and the Americas the ancient Mayans are perhaps best known for their use of their pyramids in public bloodletting rituals.

Initially established during the Preclassic period, many of the Mayan's cultural features reached their apogee of development during the following Classic period (c. 250 to 900), and continued throughout the Postclassic period until the arrival of the Spanish in the 1520s. At its peak, the Mayan Civilization was one of the most densely populated and culturally dynamic societies in the world.

The Maya civilization shares many features with other Mesoamerican civilizations due to the high degree of interaction and cultural diffusion that characterized the region. Advances such as writing, epigraphy, and the calendar did not originate with the Maya; however, their civilization fully developed them. Maya influence can be detected as far as central Mexico, more than 1000 km (625 miles) from the Maya area comprising southern Mexico and northern Central America (Guatemala, Belize, western Honduras, and El Salvador). Many outside influences also are found in Maya art and architecture, which are thought to result from trade and cultural exchange rather than direct external conquest.

The Maya peoples did not entirely disappear at the time of the Classic period decline nor with the arrival of the Spanish conquistadores and the subsequent Spanish colonization of the Americas. Rather the people have tended to remain in their home areas. Today, the Maya and their descendants form sizable populations throughout the Maya region and maintain a distinctive set of traditions and beliefs that are the result of the merger of pre-Columbian and post-Conquest ideologies (and are structured by the almost total adoption of Roman Catholicism). Many different Mayan languages continue to be spoken as primary languages today; the "Rabinal AchĂ," a play written in the Q'eqchi' language, was declared a Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO in 2005.

Origins

The Maya started to build ceremonial architecture around 1000 B.C.E. Among archaeologists there is some disagreement regarding the borders at that time period and the difference between the early Maya and their neighboring Pre-Classic Mesoamerican civilization, the Olmec culture. Eventually, the Olmec culture faded after spreading its influence into the Yucatan peninsula, present-day Guatemala, and other regions.

The earliest Mayan monuments, simple burial mounds, are precursors to the pyramids erected in later times.

The Maya developed the famed cities of Tikal, Palenque, CopĂĄn, and Kalakmul, as well as Dos Pilas, Uaxactun, Altun Ha, Bonampak, and many other sites in the area. They developed an agriculturally intensive, city-centered empire comprising numerous independent city-states. The most notable monuments of the city-states are the pyramids they built in their religious centers and the accompanying palaces of their rulers. Other important archaeological remains include the carved stone slabs usually called stelae (the Maya called them Tetun, or "Tree-stones"), which depict rulers along with hieroglyphic texts describing their genealogy, war victories, and other accomplishments.

The Maya participated in long-distance trade in Mesoamerica and possibly to lands even further afield. Important trade goods included cacao, salt, and obsidian.

Art

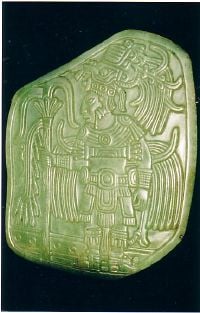

Many consider Mayan art of their Classic Era (200 to 900 C.E.) to be the most sophisticated and beautiful of the ancient New World.

The carvings and stucco reliefs at Palenque and the statuary of CopĂĄn are especially fine, showing a grace and accurate observation of the human form that reminded early archaeologists of Classical civilization of the Old World, hence the name bestowed on this era.

We have only hints of the advanced painting of the classic Maya; mostly from examples surviving on funerary pottery and other Mayan ceramics. Also, a building at Bonampak holds ancient murals that have miraculously survived. With the decipherment of the Maya script it was discovered that the Maya were one of the few civilizations whose artists attached their name to their work.

Architecture

Pyramids

As unique and spectacular as any Greek or Roman architecture, Maya architecture spans a few thousand years. Among the various forms, the most dramatic and easily recognizable as Maya are the fantastic stepped pyramids from the Terminal Pre-classic period and beyond. These pyramids relied on intricate carved stone in order to create a stair-step design.

Each pyramid was dedicated to a deity whose shrine sat at its peak. During this time in Mayan culture, the centers of their religious, commercial, and bureaucratic power grew into incredible cities, including Chichen Itza, Tikal, and Uxmal. Through observing numerous consistent elements and stylistic distinctions among the remnants of Mayan architecture, archaeologists have been able to use them as important keys to understanding the evolution of that ancient civilization.

Palaces

Large and often highly decorated, the palaces usually sat close to the center of a city and housed the population's elite. Any exceedingly large royal palace, or one comprising many chambers on different levels, might be referred to as an acropolis. However, often these were one-story and consisted of many small chambers and typically at least one interior courtyard; these structures appear to take into account the needed functionality required of a residence, as well as the decoration required for the inhabitants' stature. Archaeologists seem to agree that many palaces are home to various tombs. At CopĂĄn, beneath over four hundred years of later remodeling, a tomb for one of the ancient rulers has been discovered, and the North Acropolis at Tikal appears to have been the site of numerous burials during the Terminal Pre-classic and Early Classic periods.

âE-groupsâ

This common feature of Mayan cities remains somewhat a mystery. Appearing consistently on the western side of a plaza is a pyramid temple, facing three smaller temples across the plaza; the buildings are called "E-groups" because their layout resembles the letter "E." It has been theorized that these E-groups were observatories, due to the precise positioning of the sun through the small temples when viewed from the pyramid during the solstices and equinoxes. Other theories involve the E-groups manifesting a theme from the Maya creation story told by the relief and artwork that adorns these structures.

Temples

Often the most important religious temples sat atop the towering Maya pyramids, presumably as the closest place to the heavens. While recent discoveries point toward the extensive use of pyramids as tombs, the temples themselves rarely, if ever, contain burials. The lack of a burial chamber in the temples permitted them to offer Mayan priests up to small three rooms, which were used for various ritual purposes.

Residing atop the pyramids, some over two hundred feet tall, the temples were impressive and decorated structures themselves. Commonly topped with a roof comb, or superficial grandiose wall, these temples might also have served a propaganda purpose to uplift the Mayan rulers. As occasionally the only structure to exceed the height of the jungle, the roof combs atop the temples were often carved with representations of rulers, which could be seen from vast distances. Beneath the proud temples and lifting them up, the pyramids were, essentially, a series of successively smaller platforms split by steep stairs that would allow access to the temple.

Observatories

The Maya were keen astronomers and had mapped out the phases of celestial objects, especially the Moon and Venus. Many temples have doorways and other features aligning to celestial events. Round temples, often dedicated to Kukulcan, are perhaps those most often described as "observatories" by modern ruin tour-guides, but there is no evidence that they were so used exclusively, and temple pyramids of other shapes may well have been used for observation as well.

Ball courts

As an integral aspect of the Mesoamerican lifestyle, the courts for ritual ball games were constructed throughout the Maya realm and often on a grand scale. Enclosed on two sides by stepped ramps that led to ceremonial platforms or small temples, the ball court itself was of a capital "I" shape and could be found in all but the smallest of Mayan cities. Losers of the ball game sometimes became sacrificial victims.

Urban design

As Maya cities spread throughout the varied geography of Mesoamerica, the extent of site planning appears to have been minimal; their cities having been built somewhat haphazardly as dictated by the topography of each independent location. Mayan architecture tends to integrate a great degree of natural features. For instance, some cities sited on the flat limestone plains of the northern Yucatan grew into great sprawling municipalities, while others built in the hills of Usumacinta utilized the natural loft of the topography to raise their towers and temples to impressive heights. However, some semblance of order, as required by any large city, still prevailed.

At the onset of large-scale construction, a predetermined axis was typically established in congruence with the cardinal directions. Depending upon the location and availability of natural resources such as fresh-water wells, or cenotes, the city grew by connecting great plazas with the numerous platforms that created the sub-structure for nearly all Mayan buildings, by means of sacbeob causeways. As more structures were added and existing structures re-built or remodeled, the great Mayan cities seemed to take on an almost random identity that contrasts sharply with other great Mesoamerican cities, such as Teotihuacan with its rigid grid-like construction.

The heart of the Mayan city featured large plazas surrounded by the most valued governmental and religious buildings, such as the royal acropolis, great pyramid temples, and occasionally, ball courts. Though city layouts evolved as nature dictated, careful attention was placed on the directional orientation of temples and observatories so that they were constructed in accordance with Mayan interpretation of the orbits of the stars. Immediately outside this ritual center were the structures of lesser nobles, smaller temples, and individual shrines; the less sacred and less important structures had a greater degree of privacy. Outside of the constantly evolving urban core were the less permanent and more modest homes of the common people.

Classic Era Mayan urban design could easily be described as the division of space by great monuments and causeways. In this case, the open public plazas were the gathering places for the people and the focus of the urban design, while interior space was entirely secondary. Only in the Late Post-Classic era did the great Mayan cities develop into more fortress-like defensive structures that lacked, for the most part, the large and numerous plazas of the Classic.

Building materials

A surprising aspect of the great Mayan structures is that they appear to have been made without the use of many of the advanced technologies that would seem to be necessary for such constructions. Lacking metal tools, pulleys, and perhaps even the wheel, Mayan architects were usually assured of one thing in abundance: manpower. Beyond this enormous requirement, the remaining materials seem to have been readily available.

All stone for Maya structures appears to have been taken from local quarries. Most often this was limestone, which, while being quarried, remained pliable enough to be worked with stone toolsâonly hardening once removed from its bed. In addition to the structural use of limestone, much of the mortar used was crushed, burned, and mixed limestone that mimicked the properties of cement and was used just as widely for stucco finishing as it was for mortar. However, later improvements in quarrying techniques reduced the necessity for this limestone-stucco as the stones began to fit quite perfectly, yet it remained a crucial element in some post and lintel roofs. In the case of the common homes, wooden poles, adobe, and thatch were the primary materials. However, instances of what appear to be common houses of limestone have been discovered as well. It should be noted that in one instance from the city of Comalcalco fired clay bricks have been found as a substitute for a lack of any substantial stone deposits.

Building process

All evidence seems to suggest that most stone buildings were built on top of a platform sub-structure that varied in height from less than three feet in the case of terraces and smaller structures to 135 feet in the case of great temples and pyramids. A flight of often steep stone steps split the large stepped platforms on at least one side, contributing to the common bi-symmetrical appearance of Mayan architecture.

Depending on the prevalent stylistic tendencies of an area, these platforms most often were built of a cut and stucco stone exterior filled with densely packed gravel. As is the case with many other Mayan reliefs, those on the platforms were often related to the intended purpose of the residing structure. Thus, as the sub-structural platforms were completed, the grand residences and temples of the Maya were constructed on the solid foundations of the platforms.

As all structures were built, little attention seems to have been given to their utilitarian functionality and much to their external aesthetics; however, a certain repeated aspect, the corbeled arch, was often utilized to mimic the appearance and feel of the simple Mayan hut. Though not an effective tool for increasing increase interior space, as it required thick stone walls to support the high ceiling, some temples utilized repeated arches, or a corbeled vault, to construct what the Maya referred to as pibnal, or âsweatbath,â such as those in the Temple of the Cross at Palenque. As structures were completed, typically extensive relief work was added, often simply to the covering of stucco used to smooth any imperfections. However, many lintel carvings have been discovered, as well as actual stone carvings used as a facade. Commonly, these would continue uninterrupted around an entire structure and contain a variety of artwork pertaining to the inhabitants or purpose of a building. Though not the case at all Mayan locations, broad use of painted stucco has been discovered as well.

It has been suggested that, in conjunction with the Maya Long Count Calendar, every 52 years, or cycle, temples and pyramids were remodeled and rebuilt. It appears now that the rebuilding process was often instigated by a new ruler or for political matters, as opposed to matching the calendar cycle. In any case, the process of rebuilding on top of old structures is a common one: most notably, the North Acropolis at Tikal seems to be the sum total of 1,500 years of recurring architectural modifications.

Religion

Like the Aztec and Inca who came to power later, the Maya believed in a cyclical nature of time. The rituals and ceremonies were very closely associated with hundreds of celestial and terrestrial cycles, which they observed and inscribed as separate calendars, all of infinite duration. The Maya shaman had the job of interpreting these cycles and giving a prophetic outlook on the future or past based on the number relations of all their calendars. If the interpretations of the shaman spelled bad times to come, sacrifices would be performed to appease the gods.

The Maya, like most pre-modern societies, believed that the cosmos has three major planes: the underworld, the sky, and the earth. The Mayan Underworld was reached through caves and ball courts. It was thought to be dominated by the aged Mayan gods of death and putrefaction. The Sun and Itzamna, both aged gods, dominated the Mayan idea of the sky. The night sky was considered a window showing all supernatural doings. The Maya configured constellations of gods and places, saw the unfolding of narratives in their seasonal movements, and believed that the intersection of all possible worlds was in the night sky.

Mayan gods were not discrete, separate entities like Greek gods. The gods had affinities and aspects that caused them to merge with one another in ways that seem unbounded. There is a massive array of supernatural characters in the Mayan religious tradition, only some of which recur with regularity. Good and evil traits are not permanent characteristics of Mayan gods, nor are only "good" traits admirable. What is inappropriate during one season might be acceptable in another since much of the Mayan religious tradition is based on cycles and not permanence.

The life-cycle of maize (corn) lies at the heart of Maya belief. This philosophy is demonstrated in the Mayan belief in the Maize God as a central religious figure. The Mayan bodily ideal is also based on the form of the young Maize God, which is demonstrated in their artwork. The Maize God was also a model of courtly life for the Classical Maya.

It is sometimes believed that the multiple gods represented nothing more than a mathematical explanation of what they observed. Each god was simply a number or an explanation of the effects observed by a combination of numbers from multiple calendars. Among the many types of Mayan calendars which were maintained, the most important included a 260 day cycle that approximated the solar year, a cycle that recorded the periods of the moon, and also one that tracked the synodic period of Venus.

As late as the nineteenth century, Maya influence was evident in the local branch of Christianity followed in some parts of Mexico. Among the Kiâche's in the western highlands of Guatemala, the Mayan calendar is still replicated to this day in the training of the ajk'ij, the keepers of the 260 day calendar called ch'olk'ij.

Interestingly, the Maya did not seem to strongly distinguish between past, present, and future. Instead they used one word to describe all instances of time, which can be translated as "it came to pass." Philosophically, the Maya believed that knowing the past meant knowing the cyclical influences that create the present, and by knowing the influences of the present one can see the cyclical influences of the future.

The multiple gods of Maya religion also represented a mathematical explanation of what they observed. The Maya knew long before Johannes Kepler that the planets have elliptical orbits and used their findings to support their view of the cyclical nature of time.

The Maya believed that the universe was flat and square, but infinite in area. They also worshiped the circle, which symbolized perfection or the balancing of forces. Among other religious symbols were the swastika and the perfect cross.

Mayan rulers figured prominently in many religious rituals and were often required to practice bloodletting, a medical practice that used sculpted bone or jade instruments to perforate the patient's penis, or drawing thorn-studded ropes through their tongues.

Astronomy

Uniquely, there is some evidence to suggest that the Maya may have been the only pre-telescopic civilization to demonstrate knowledge of the Orion Nebula as being fuzzy (not a stellar pinpoint). The information supporting this theory comes from a folk tale that deals with the Orion constellation's area of the sky. Traditional Mayan hearths include a smudge of glowing fire in the middle that corresponds with the Orion Nebula. This is a significant clue to support the idea that before the telescope was invented the Maya detected a diffuse area of the sky contrary to the pinpoints of stars.

The Maya were very interested in zenial passages, the time when the sun passes directly overhead. The latitude of most of their cities being below the Tropic of Cancer, these zenial passages would occur twice a year equidistant from the solstice.

Writing and literacy

The Maya writing system (often called hieroglyphics because of its superficial resemblance to the Ancient Egyptian writing) was a combination of phonetic symbols and logograms. It is most often classified as a logographic or, more properly, a logosyllabic writing system, in which syllabic signs play a significant role. It is the only writing system of the Pre-Columbian New World that is known to completely represent the spoken language of its community. In total, the script has more than one thousand different glyphs, although a few are variations of the same sign or meaning, and many appear only rarely or are confined to particular localities. At any one time, no more than around five hundred glyphs were in use, some two hundred of which, including variations, and had a phonetic or syllabic interpretation.

The earliest inscriptions in an identifiably Mayan script date back to the first century B.C.E. However, this is preceded by several other writing systems that had developed in Mesoamerica, most notably that of the Olmec culture, which originated around 700â500 B.C.E. The Mayan system is believed by Mayanist scholars to have derived from this earlier script; however, in the succeeding centuries, the Maya developed their script into a form that was far more complete and complex than that of its predecessors.

Since its inception, the Mayan script was in use up to the arrival of Europeans, peaking during the Maya Classical Period (200â900 C.E.).

At a rough estimate, around ten thousand individual texts have so far been recovered, mostly inscribed on stone monuments, lintels, stelae, and ceramic pottery. Mayan civilization also produced numerous texts using the bark of certain trees in a book-format called a codex. Shortly after the conquest, all of these texts that could be found were ordered to be burned and destroyed by zealous Spanish priests, notably Bishop Diego de Landa. Out of these Mayan codices, only three reasonably intact examples are known to have survived to the present day. These are now known as the Madrid, Dresden, and Paris codices.

Although the archaeological record does not provide examples, Mayan art itself carries evidence that writing was done with brushes made with animal hair and quills. Codex-style writing was usually done in black ink with red highlights, giving rise to the Aztec name for the Mayan territory as the "land of red and black."

Scribes held a prominent position in Mayan courts. Mayan art often depicts rulers with trappings indicating they were scribes, or at least able to write, such as having pen bundles in their headdresses. Additionally, many rulers have been found in conjunction with writing tools such as shell or clay inkpots.

Although the number of logograms and syllabic symbols required to fully write the language numbered in the hundreds, literacy was not necessarily widespread beyond the elite classes. Graffiti uncovered in various contexts, including on fired bricks, shows nonsensical attempts to imitate the writing system.

Mathematics

The Maya (or their Olmec predecessors) independently developed the concept of zero, and used a base 20 numbering system. Inscriptions show them on occasion working with sums up to the hundreds of millions and dates so large it would take several lines just to represent it. They produced extremely accurate astronomical observations; their charts of the movements of the moon and planets are equal or superior to those of any other civilization working from naked-eye observation.

Mayan priests and astronomers produced a highly accurate measure of the length of the solar year, far more accurate than that used in Europe as the basis of the Gregorian Calendar.

Agriculture

The ancient Maya had diverse and sophisticated methods of food production. It was formerly believed that slash and burn agriculture provided most of their food. However, it is now thought that permanent raised fields, terraces, forest gardens, managed fallows, and wild harvesting were also crucial to supporting the large populations of the Classic period in some areas.

Contemporary Mayan people still practice many of these traditional forms of agriculture, although they are dynamic systems and evolve with changing population pressures, cultures, economic systems, climate changes, and the availability of synthetic fertilizers and pesticides.

Decline of the Maya

In the eighth and ninth century centuries C.E., Classic Mayan culture went into decline, with most of the cities of the central lowlands abandoned. Warfare, ecological depletion of croplands, and drought (or some combination of these) are usually suggested as reasons for the decline. There is archaeological evidence of warfare, famine, and revolt against the elite at various central-lowlands sites.

The Mayan cities of the northern lowlands in Yucatan continued to flourish for centuries more; some of the important sites in this era were Chichen Itza, Uxmal, EdznĂĄ, and Coba. After the decline of the ruling dynasties of Chichen and Uxmal, Mayapan ruled all of Yucatan until a revolt in 1450 C.E.; the area then devolved to city states until the Spanish Conquest.

The Itza Maya, Kowoj, and Yalain groups of Central Peten survived the "Classic Period Collapse" in small numbers and by 1250 C.E. reconstituted themselves to form competing polities. The Itza Kingdom had its capital at Noj Peten, an archaeological site thought to underlay modern day Flores, Guatemala. It ruled over a polity extending across the Peten Lakes region, encompassing the community of Eckixil on Lake Quexil.[1] These sites and this region were inhabited continuously by independent Maya until after the final Spanish Conquest of 1697 C.E.

Post-Classic Mayan states also continued to thrive in the southern highlands. One of the Mayan kingdoms in this area, the Quiché, is responsible for the best-known Mayan work of historiography and mythology, the Popol Vuh.

The Spanish started their conquest of the Mayan lands in the 1520s. Some Mayan states offered long, fierce resistance; the last Mayan state, the Itza Kingdom, was not subdued by Spanish authorities until 1697.

Rediscovery of the Pre-Columbian Maya

The Spanish American Colonies were largely cut off from the outside world and the ruins of the great ancient cities were little known except to locals. In 1839 United States traveler and writer John Lloyd Stephens, hearing reports of lost ruins in the jungle, visited CopĂĄn, Palenque, and other sites with English architect and draftsman Frederick Catherwood. Their illustrated accounts of the ruins sparked strong interest in the region and the people, and led to the subsequent discoveries of Mayan cities whose discovery and excavation permitted them to assume their rightful place in the records of the Mesoamerican heritage.

Much of the contemporary rural population of Guatemala and Belize is Mayan by descent and primary language; a Mayan culture still exists in rural Mexico.

Notes

- â Kevin R. Schwarz, Understanding the Classic to Postclassic Architectural Transformation of Rural Households and Communities in the Quexil-Petenxil Basins, El PetĂ©n, Guatemala. Retrieved June 18, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Coe, Michael D. Breaking the Maya Code. London: Thames & Hudson, 1992 ISBN 0500050619

- Coe, Michael D. The Maya. New York: Thames & Hudson. 1999. ISBN 0500280665

- Coggins, Clemency, ed. Artifacts from the Cenote of Sacrifice Chichen Itza, Yucatan: Textiles, Basketry, Stone, Shell, Ceramics, Wood, Copal, Rubber (Memoirs of the Peabody Museum). Harvard University. 1992. ISBN 0873656946

- Culbert, T. Patrick, ed. Classic Maya Collapse. University of New Mexico, 1977. ISBN 082630463X

- Drew, David. The Lost Chronicles of the Maya Kings. London: Phoenix. 2004. ISBN 0753809893

- Krupp, Edward C. âIgniting the Hearth.â Sky & Telescope (February 1999): 94.

- Miller, Mary, and Martin, Simon. Courtly Art of the Ancient Maya. London: Thames & Hudson, 2004. ISBN 0500051291

- Schele, Linda, and David Freidel. A Forest of Kings: The Untold Story of the Ancient Maya. Reprint, New York: Harper Perennial, 1990. ISBN 0688112048.

- Webster, David L. The Fall of the Ancient Maya. London: Thames & Hudson, 2002. ISBN 0500051135

External links

All links retrieved April 29, 2025.

- Lost Civilizations. Mayan History. Maya.

- Mayan Epigraphic Language Database

- Mesoweb. An Exploration of Mesoamerican Cultures

- Nova Online "Lost King of the Mayas" PBS.org

- Nova Online "Cracking the Maya Code" PBS.org

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.