Torah

The Torah (from Hebrew ◊™÷ľ◊ē÷Ļ◊®÷ł◊Ē: meaning "teaching," "instruction," or "law") refers to most important scriptures of Judaism that are the foundation of the Hebrew Bible (Tanakh). According to Jewish tradition, the Torah was revealed by God to Prophet Moses and thus is considered to be the word of God. It consists of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, and, consequently, is also called the Pentateuch (five books). The titles of these five books are:

- Genesis (◊Ď◊®◊ź◊©◊ô◊™, Bereshit: "In the beginning‚Ķ ")

- Exodus (◊©◊ě◊ē◊™, Shemot: "Names")

- Leviticus (◊ē◊ô◊ß◊®◊ź, Vayyiqra: "And he called‚Ķ ")

- Numbers (◊Ď◊ě◊ď◊Ď◊®, Bamidbar: "In the desert‚Ķ ")

- Deuteronomy (◊ď◊Ď◊®◊ô◊Ě, Devarim: "Words" or "Discourses")[1]

In Judaism, the term "Torah" is also used to include both Judaism's written law, as found in the Pentateuch, and oral law, encompassing the entire spectrum of authoritative Jewish religious teachings throughout history, including the Mishnah, the Talmud, the Midrash, and more. The basis for the doctrine of Oral Torah comes from the rabbinic teaching that Moses passed down to subsequent generations numerous instructions and guidance that were not written down in the text of the written Law.

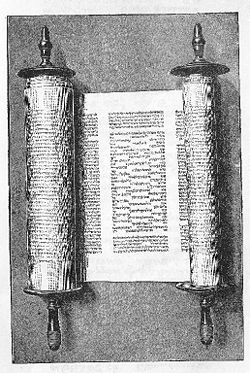

The Torah, being the core of Judaism, is naturally also the core of the synagogue. As such, the Torah is "dressed" often with a sash, various ornaments and often (but not always) a crown (customs vary). Torah scrolls, called a Sefer Torah ("Book [of] Torah"), are still used for Jewish religious services and are stored in the holiest part of the synagogue in the Ark known as the "Holy Ark" (◊ź÷≤◊®◊ē÷Ļ◊ü ◊Ē◊ß÷Ļ◊ď◊©◊Ā aron hakodesh in Hebrew.)

Jews have revered the Torah through the ages, as have Samaritans and Christians. Jesus regarded the Torah as authoritative, and his Great Commandment (Matt. 22:36-40) that is a summary of the duties of humans before God is based on two commandments from the Torah:

"Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind (Deuteronomy 6:5)." This is the first and greatest commandment. And the second is like it: "Love your neighbor as yourself (Leviticus 19:18)." All the Law (Torah) and the Prophets hang on these two commandments.

Muslims too have traditionally regarded the Torah as the literal word of God as told to Moses. For many, it is neither exactly history, nor theology, nor a legal and ritual guide, but something beyond all three. It is the primary guide to the relationship between God and humanity, a living document that unfolds over generations and millennia.

Various Titles

The Torah is also known as the Five Books of Moses, the Book of Moses, the Law of Moses (Torat Moshe ◊™÷ľ◊ē÷Ļ◊®÷∑◊™÷ĺ◊ě÷Ļ◊©÷∂◊Ā◊Ē), Sefer Torah in Hebrew (which refers to the scroll cases in which the books were kept), or Pentateuch (from Greek ő†őĶőĹŌĄőĶŌĄőĶŌćŌáŌČŌā "five rolls or cases"). A Sefer Torah is a formal written scroll of the five books, written by a Torah scribe under exceptionally strict requirements.

Other Hebrew names for the Torah include Hamisha Humshei Torah (◊ó◊ě◊©◊Ē ◊ó◊ē◊ě◊©◊ô ◊™◊ē◊®◊Ē, "[the] five fifths/parts [of the] Torah") or simply the Humash (◊ó◊ē÷ľ◊ě÷ł◊©◊Ā "fifth").

Contents

This is a brief summary of the contents of the books of the Pentateuch: (For further details see the individual books.)

Genesis begins with the story of Creation (Genesis 1-3) and Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, as well the account of their descendants. Following these are the accounts of Noah and the great flood (Genesis 3-9), and his descendants. The Tower of Babel and the story of (Abraham)'s covenant with God (Genesis 10-11) are followed by the story of the patriarchs, Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, and the life of Joseph (Genesis 12-50). God gives to the Patriarchs a promise of the land of Canaan, but at the end of Genesis the sons of Jacob end up leaving Canaan for Egypt because of a famine.

Exodus is the story of Moses, who leads Israelites out of Pharaoh's Egypt (Exodus 1-18) with a promise to take them to the promised land. On the way, they camp at Mount Sinai/Horeb where Moses receives the Ten Commandments from God, and mediates His laws and Covenant (Exodus 19-24) the people of Israel. Exodus also deals with the violation of the commandment against idolatry when Aaron took part in the construction of the Golden Calf (Exodus 32-34). Exodus concludes with the instructions on building the Tabernacle (Exodus 25-31; 35-40).

Leviticus Begins with instructions to the Israelites on how to use the Tabernacle, which they had just built (Leviticus 1-10). This is followed by rules of clean and unclean (Leviticus 11-15), which includes the laws of slaughter and animals permissible to eat (see also: Kashrut), the Day of Atonement (Leviticus 16), and various moral and ritual laws sometimes called the Holiness Code (Leviticus 17-26).

Numbers takes two censuses where the number of Israelites are counted (Numbers 1-3, 26), and has many laws mixed among the narratives. The narratives tell how Israel consolidated itself as a community at Sinai (Numbers 1-9), set out from Sinai to move towards Canaan and spied out the land (Numbers 10-13). Because of unbelief at various points, but especially at Kadesh Barnea (Numbers 14), the Israelites were condemned to wander for forty years in the desert in the vicinity of Kadesh instead of immediately entering the promised land. Even Moses sins and is told he would not live to enter the land (Numbers 20). At the end of Numbers (Numbers 26-35) Israel moves from the area of Kadesh towards the promised land. They leave the Sinai desert and go around Edom and through Moab where Balak and Balaam oppose them (Numbers 22-24; 31:8, 15-16). They defeat two Transjordan kings, Og and Sihon (Numbers 21), and so come to occupy some territory outside of Canaan. At the end of the book they are on the plains of Moab opposite Jericho ready to enter the Promised Land.

Deuteronomy consists primarily of a series of speeches by Moses on the plains of Moab opposite Jericho exhorting Israel to obey God and further instruction on His Laws. At the end of the book (Deuteronomy 34), Moses is allowed to see the promised land from a mountain, but it is never known what happened to Moses on the mountain, but he was never seen again. Soon afterwards Israel begins the conquest of Canaan.

Classical Judaism recognizes the Torah as containing a complete system of laws, particularly the 613 mitzvot ("commandments"), the divine law that governs the life of observant Jews. For observant Jews, the Torah signifies pre-eminently these laws, which are merely framed by the narrative.

Authorship

According to classical Judaism, Moses was traditionally regarded as the author of the Torah, receiving it from God either as divine inspiration or as direct dictation together with the Oral Torah.

Rabbinic writings offer various ideas on when the entire Torah was actually revealed to the Jewish people. The revelation to Moses at Mount Sinai is considered by many to be the most important revelatory event. According to dating of the text by Orthodox rabbis this occurred in 1280 B.C.E. Some rabbinic sources state that the entire Torah was given all at once at this event. In the maximalist belief, this dictation included not only the "quotes" which appear in the text, but every word of the text itself, including phrases such as "And God spoke to Moses…," and included God telling Moses about Moses' own death and what would happen afterward. Other classical rabbinic sources hold that the Torah was revealed to Moses over many years, and finished only at his death. Another school of thought holds that although Moses wrote the vast majority of the Torah, a number of sentences throughout the Torah must have been written after his death by another prophet, presumably Joshua. Abraham ibn Ezra and Joseph Bonfils observed that some phrases in the Torah present information that people should only have known after the time of Moses. Ibn Ezra hinted, and Bonfils explicitly stated, that Joshua (or perhaps some later prophet) wrote these sections of the Torah. Other rabbis would not accept this belief.

Modern scholarship on the pentateuch holds to the theory of multiple authorship called the Documentary Hypothesis. In this view, the text was composed over more than 1000 years from the earliest poetical verses, an Israelite epic called "J" dating from the time of King Solomon, a Northern version ("E"), a separate book of Deuteronomy ("D") composed in the seventh century, and priestly sources ("P"), all brought together in a long process until the Pentateuch reached its final form in the days of Ezra the scribe.

The Talmud (tractate Sabb. 115b) states that a peculiar section in the Book of Numbers (10:35-36, surrounded by inverted Hebrew letter nuns) in fact forms a separate book. On this verse a midrash on the book of Proverbs states that "These two verses stem from an independent book which existed, but was suppressed!" Another (possibly earlier) midrash, Ta'ame Haserot Viyterot, states that this section actually comes from the book of prophecy of Eldad and Medad. The Talmud says that God dictated four books of the Torah, but that Moses wrote Deuteronomy in his own words (Meg. 31b). All classical beliefs, nonetheless, hold that the Torah was entirely or almost entirely Mosaic and of divine origin.[2]

The Torah as the Heart of Judaism

The Torah is the primary document of Judaism. According to Jewish tradition it was revealed to Moses by God.

According to the Talmudic teachings the Torah was created 974 generations before the world was created. It is the blueprint that God used to create the world. Everything created in this world is for the purpose of carrying out the word of the Torah, and that the foundation of all that the Jews believe in stems from the knowledge that the Lord is the God who created the world.

Production and usage of a Torah scroll

Manuscript Torah scrolls are still used, and still scribed, for ritual purposes (i.e. religious services); this is called a Sefer Torah ("Book [of] Torah"). They are written using a painstakingly careful methodology by highly qualified scribes. This has resulted in modern copies of the text that are unchanged from millennia old copies. The reason for such care is it is believed that every word, or marking, has divine meaning, and that not one part may be inadvertently changed lest it lead to error.

Printed versions of the Torah in normal book form (codex) are known as a Chumash (plural Chumashim) ("[Book of] Five or Fifths"). They are treated as respected texts, but not anywhere near the level of sacredness accorded a Sefer Torah, which is often a major possession of a Jewish community. A chumash contains the Torah and other writings, usually organized for liturgical use, and sometimes accompanied by some of the main classic commentaries on individual verses and word choices, for the benefit of the reader.

Torah scrolls are stored in the holiest part of the synagogue in the Ark known as the "Holy Ark" (◊ź÷≤◊®◊ē÷Ļ◊ü ◊Ē◊ß÷Ļ◊ď◊©◊Ā aron hakodesh in Hebrew.) Aron in Hebrew means 'cupboard' or 'closet' and Kodesh is derived from 'Kadosh', or 'holy'. The Torah is "dressed" often with a sash, various ornaments and often (but not always) a crown.

The divine meaning of individual words and letters

The Rabbis hold that not only do the words of the Torah provide a Divine message, but they also indicate a far greater message that extends beyond them. Thus the Rabbis hold that even as small a mark as a kotzo shel yod (◊ß◊ē◊¶◊ē ◊©◊ú ◊ô◊ē◊ď), the serif of the Hebrew letter yod (◊ô), the smallest letter, or decorative markings, or repeated words, were put there by God to teach scores of lessons. This is regardless of whether that yod appears in the phrase "I am the Lord thy God," or whether it appears in "And God spoke unto Moses saying." In a similar vein, Rabbi Akiva, who died in 135 C.E., is said to have learned a new law from every et (◊ź◊™) in the Torah (Talmud, tractate Pesachim 22b); the word et is meaningless by itself, and serves only to mark the accusative case. In other words, the Orthodox belief is that even an apparently simple statement such as "And God spoke unto Moses saying‚Ķ " is no less important than the actual statement.

The Biblical Hebrew language is sometimes referred to as "the flame alphabet" because many devout Jews believe that the Torah is the literal word of God written in fire.

The Oral Torah

Many Jewish laws are not directly mentioned in the written Torah, but are derived from the oral tradition, or oral Torah.

Jewish tradition holds that the written Torah was transmitted in parallel with the oral tradition. Jews point to texts of the Torah, where many words and concepts are left undefined and many procedures mentioned without explanation or instructions; the reader is required to seek out the missing details from the oral sources. For example, many times in the Torah it says that/as you are/were shown on the mountain in reference of how to do a commandment (Exodus 25:40).

According to classical rabbinic texts this parallel set of material was originally transmitted to Moses at Sinai, and then from Moses to Israel. At that time it was forbidden to write and publish the oral law, as any writing would be incomplete and subject to misinterpretation and abuse.

However, after exile, dispersion and persecution, this tradition was lifted when it became apparent that in writing was the only way to ensure that the Oral Law could be preserved. After many years of effort by a great number of tannaim, the oral tradition was written down around 200 C.E. by Rabbi Judah haNasi who took up the compilation of a nominally written version of the Oral Law, the Mishnah. Other oral traditions from the same time period that had not been entered into the Mishnah were recorded as "Baraitot" (external teaching), and the Tosefta. Other traditions were written down as Midrashim.

Over the next four centuries, this record of laws and ethical teachings provided the necessary signals and codes to allow the continuity of the same Mosaic Oral traditions to be taught and passed on in Jewish communities scattered across both of the world's major Jewish communities (from Israel to Babylon).

As rabbinic Judaism developed over the succeeding centuries, many more lessons, lectures and traditions only alluded to in the few hundred pages of the Mishnah, became the thousands of pages now called the Gemara. The Gemara was written in the Aramaic language, having been compiled in Babylon. The Mishnah and Gemara together are called the Talmud. The Rabbis in Israel also collected their traditions and compiled them into the Jerusalem Talmud. Since the greater number of Rabbis lived in Babylon, the Babylonian Talmud had precedence if the two were found in conflict.

Orthodox Jews and Conservative Jews accept these texts as the basis for all subsequent halakha and codes of Jewish law, which are held to be normative. Reform and Reconstructionist Jews deny that these texts may be used for determining normative law (laws accepted as binding), but accept them as the authentic and only Jewish version of understanding the Bible and its development throughout history.

The Place of the Torah in Christianity

In Christianity, the Pentateuch forms the beginning of the Old Testament. Thus, the Christian Bible incorporates the Torah into its canon. The Torah was translated into several Greek versions, being included in the Septuagint which was the Bible of the early Christian church.

Nevertheless, Christianity does not accept the laws of the Torah as binding in every respect. On the one hand, Jesus is said to have respected the authority of Torah; particularly in Matthew's gospel where he said,

- Do not think that I have come to abolish the Law (Torah) or the Prophets; I have not come to abolish them but to fulfill them. I tell you the truth, until heaven and earth disappear, not the smallest letter, not the least stroke of a pen, will by any means disappear from the Law until everything is accomplished. Anyone who breaks one of the least of these commandments and teaches others to do the same will be called least in the kingdom of heaven. (Matthew 5:17-19)

On the other hand, Saint Paul taught that the Torah was not binding on gentile Christians, who were saved through Christ. They need not convert to Judaism and be placed under the commandments of the Law, but were justified "apart from the Law." As the years passed and the number of Jewish Christians declined to insignificance, the church became essentially a Gentile church, where the Law was no longer binding. Commandments of the Torah, including circumcision, kashrut and observance of the Jewish Sabbath were not required of Christians. More than that, Christians should not do such things, since by thinking that their salvation was somehow advantaged by keeping the Torah they were denying the efficacy of Christ's sacrifice as all-sufficient for the redemption of sin.

Thus, while Christians value the narrative portions of the Torah, the stories of Moses and the Patriarchs, as part of Christian history and as providing lessons for believers' lives of faith, they largely disregard the commandments of the Torah. Most believe that the Torah constitutes the covenant with the Jews, while Christians have a different covenant, established through the blood of Christ.

Most Protestants believe that the laws of the Torah should be understood thus:

- The Law reveals our sinfulness, since no one can keep the commandments 100 percent.

- The commandments of the Law are valid for Christians only when they have been reaffirmed in the New Testament, as when in the Sermon on the Mount Jesus reaffirms the Ten Commandments (Matt. 5:21-37). This principle affirms the ethical laws of the Torah while filtering out its ritual commandments.

- The ritual laws in the Torah are binding only upon Jews, and do not figure in Christian worship. However, while Christians worship in their own manner, there may be some influences from the Torah that informs it. Notably, while Christians keep Sunday instead of the Jewish Sabbath, their manner of keeping Sunday as a day of rest is influenced by Torah principles.

- Christians can celebrate the Torah as the word of God for Israel and appreciate it for its revelation of God's mercy and justice.

- The commandments of the Law are instructive for governing authorities, who should enact their criminal and civil laws in accordance with the law codes of God's people Israel.[3]

In Islam

Islam affirms that Moses (Musa) was given a revelation, the Torah, which Muslims call Tawrat in Arabic, and believe it to be the word of God. The Qur'an's positive view of the Torah is indicated by this verse:

Lo! We did reveal the Torah, wherein is guidance and a light, by which the prophets who submitted to God judged the Jews, as did the rabbis and the doctors of the law, because they were required to guard God’s Book, and to which they were witnesses. (Surah 5:44)

The Qur'an also indicates that the Torah is still binding on Jews today, just as the Qur'an is binding on Muslims:

- For each (community of faith) We have appointed a divine law and a traced-out way. (Surah 5:48)

However, many Muslims also believe that this original revelation was modified (tahrif, literally meaning corrupted) over time by Jewish and Christian scribes and preachers. This leads to varying attitudes to those who keep the Torah, from respect to rejection.

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ The Hebrew names are taken from initial words within the first verse of each book, with their names and pronunciations.

- ‚ÜĎ Shalom Carmy (ed.), Modern Scholarship in the Study of Torah: Contributions and Limitations; Aryeh Kaplan, Handbook of Jewish Thought Volume I (Orthodox Forum. Jason Aronson, Inc., 1996).

- ‚ÜĎ Gordon D. Fee and Douglas Stuart, How to Read the Bible for All Its Worth 3rd edition (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2003, ISBN 0310246040), 163-180.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Alter, Robert (ed.). The Five Books of Moses: A Translation with Commentary. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2004. ISBN 0393019551

- Carmy, Shalom (ed.). Modern Scholarship in the Study of Torah: Contributions and Limitations. Orthodox Forum. Jason Aronson, Inc., 1996. ISBN 978-1568214504

- Chavel, Charles B. Ramban: Commentary on the Torah. 5 vols. New York: Shilo Publishing House, Inc., 1971.

- Cohen, A. The Soncino Chumash. London: Soncino Press, 1956.

- Dever, William G. Who Were the Early Israelites? Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2006. ISBN 0802844162

- Fee, Gordon D., and Douglas Stuart. How to Read the Bible for All Its Worth, 3rd edition. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2003, 163-180. ISBN 0310246040

- Fields, Harvey J. A Torah Commentary for Our Times. 3 vols. New York: Union of American Hebrew Congregations, 1998. ISBN 0807405302

- Finkelstein, Israe, and Neil A. Silberman. The Bible Unearthed. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2001. ISBN 0684869128

- Fox, 'Everett. The Five Books of Moses. Dallas: Word Publishing, 1995.

- Friedman, Richard Elliott. Commentary on the Torah. San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 2003. ISBN 0060507179

- Hertz, J.H. The Pentateuch and Haftorahs. London: Soncino Press, 1985.

- Hirsch, Samson Raphael, and Isaac Levy (ed.). The Pentateuch. 7 vols. London: Judaica Press, 1999.

- Kaplan, Aryeh. Handbook of Jewish Thought. Volume I, Moznaim Pub.

- Kushner, Lawrence, and Kerry M. Olitzky. Sparks Beneath the Surface; A Spiritual Commentary on the Torah. Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson, 1992. ISBN 1568210167

- Lieber, David. Etz Hayim: Torah and Commentary. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 2001. (a Conservative standard)

- Leibowitz, Nehama. New Studies in the Weekly Sidra. 7 vols. Jerusalem: Hemed Press.

- Munk, Elie. The Call of the Torah: An Anthology of Interpretation and Commentary on the Five Books of Moses. 5 vols. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications Ltd., 1994.

- Plaut, W. Gunther, Bernard Bamberger, and William W. Hallo. The Torah: A Modern Commentary. New York: Union of American Hebrew Congregations, 1981. (a Reform standard)

- Rouvière, Jean-Marc. Brèves méditations sur la création du monde. Paris: L'Harmattan 2006.

- Sarna, Nahum M. and Chaim Potok (eds.). JPS Torah Commentary. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1996. ISBN 0827603312

- Scherman, Nosson. The Chumash: Stone Edition of the Artscroll Chumash. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications Ltd., 1994. (an Orthodox standard)

- "Pentateuch." Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1913.

External links

All links retrieved April 30, 2023.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.