New Kingdom of Egypt

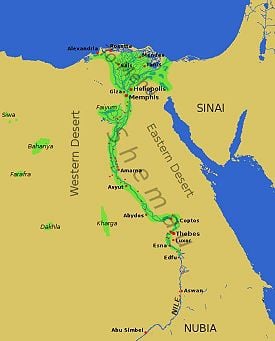

The New Kingdom is the period in ancient Egyptian history between the sixteenth century B.C.E. and the eleventh century B.C.E., covering the Eighteenth, Nineteenth, and Twentieth Dynasties of Egypt. The New Kingdom (1570â1070 B.C.E.) followed the Second Intermediate Period, and was succeeded by the Third Intermediate Period. More is known about this period than about earlier periods of Egyptian history and almost all of the Pharaohâs mummies have been found. At the greatest, the New kingdom stretched from Nubia in the South to the Euphrates in the North.[1] Some of the most famous of all the Pharaohs, such as Ramesses II and Akhenaten who tried to introduce monotheism, lived during the New Kingdom. As with the two other periods of Egyptian history known as âKingdomsâ this one ended with a breakdown of central authority. It also ended with threats from the Kush in the South and from the Assyrians in the North. The New Kingdom was followed by the first major series of foreign dynasties, including the 23rd from Mibya, the 25th from Nubia and the Persians dynasties (27th-30th) until Egypt fell to Alexander the Great in 332 B.C.E. Although archeology is still uncovering new data on Ancient Egypt, one result of the end of Egyptian independence was that much knowledge, as well as aspects of Egyptian religion, became the common property of the Mediterranean world, making a valuable contribution of the Classical Legacy to which the rest of the world and modernity itself owes so much.

Background

Possibly as a result of the foreign rule of the Hyksos during the Second Intermediate Period, the New Kingdom saw Egypt attempt to create a buffer between the Levant and Egypt, and attain its greatest territorial extent. It expanded far south into Nubia and held wide territories in the Near East. Egyptian armies fought Hittite armies for control of modern-day Syria.

The New Kingdom begins with the Eighteenth Dynasty, when its founder, Ahmose I put an end to Hyksos rule around about 1550 B.C.E. and over two-hundred years of foreign domination. The Eighteenth Dynasty contained some of Egypt's most famous Pharaohs including Ahmose I, Hapshepsut, Thutmose III, Amenhotep III, Akhenaten and Tutankhamun. Queen Hatshepsut concentrated on expanding Egypt's external trade, sending a commercial expedition to the land of Punt. Thutmose III ("the Napoleon of Egypt") expanded Egypt's army and wielded it with great success. The Biblical Exodus of the Hebews took place at some point during this era, even if Rameses II is not the Pharaoh depicted in the Bible.

One of the best-known Eighteenth Dynasty pharaohs is Amenhotep IV, who changed his name to Akhenaten in honor of the Aten and whose exclusive worship of the Aten is often interpreted as history's first instance of monotheism (and was argued in Sigmund Freud's Moses and Monotheism to have been the ultimate origin of Jewish monotheism).[2] Akhenaten's religious fervor is cited as the reason why he was subsequently written out of Egyptian history. Under his reign, in the fourteenth century B.C.E., Egyptian art flourished and attained an unprecedented level of realism.

Another celebrated pharaoh is Ramesses II ("the Great") of the Nineteenth Dynasty, who sought to recover territories in the Levant that had been held by Eighteenth Dynasty Egypt. His campaigns of reconquest culminated in the Battle of Kadesh, where he led Egyptian armies against those of the Hittite king Muwatalli II and was caught in history's first recorded military ambush. Ramesses II was famed for the huge number of children he sired by his various wives and concubines; the tomb he built for his sons, many of whom he outlived, in the Valley of the Kings has proven to be the largest funerary complex in Egypt. Egypt was probably most prosperous under Rameses II. Still greater military ability, if less self-promotion, was shown by Ramesses III.

Decline

As with the two previous periods known as Kingdoms, the New Kingdom declined when central authority grew weak and regional authority grew stronger. The Pharaohsâ power was also weakened by the rise in influence of the High Priests of Amun at Thebes, who founded the 21st dynasty at the start the Third Intermediate Period although their rule did not cover the whole of Egypt due to the autonomy of local nomarchs (regional rulers). Technically, the Pharaohs were High Priests and appointed Deputiesâquite often of royal bloodâto act for them. However, during the Second Intermediate Period the power of the appointed Priest increased, and continued to do so throughout the New Kingdom and by the end of the 20th dynasty he was effectively ruling Egypt. During the 18th dynasty, Thutmose I tried to limit the High Priestâs role to religious affairs and a lay administrator was appointed.[3]

The 23rd dynasty was started by a noble family of Libyan descent, while the 25th dynasty was founded by a Kush family from Nubia, who first rebelled then seized control of a significant portion of Egypt. The Assyrians had been threatening Egypt from the North for some time and in âthe first half of the seventh centuryâ B.C.E. they âpenetrated Egypt, exercising âpower through local vassalsâ.[4] Although the 26th dynasty succeeded in throwing off foreign domination and revived Egyptian culture with canal building and possibly circumnavigating Africa, Egyptâs days of independence were numbered and by 522 B.C.E. Egypt was under Assyrian rule, followed by the Persians, the Greeks and finally by the Romans.

)

Legacy

The architectural legacy of the New Kingdom includes some of the best known ancient monuments, such as the Valleys of the Kings, the Valley of the Queens and Abu Simbel, built by the great Rameses II and dedicated to himself and to his Queen, Nefertiti. While the lesson that national unity equaled national prosperity was not properly learned despite the evidence of history and this kingdom, as had the two previous kingdom-eras, ended in disunity and decline, one positive result was that the Greek and Roman conquerors found Egyptian civilization so rich that they helped to diffuse much mathematical, geographical, navigational knowledge, as well as Egyptian religious beliefs, within the ancient Mediterranean world. The Egyptians excelled at surveying and mapping, for example in which they were much more advanced than the Greeks. The city of Alexandria became a bridge between Ancient Egypt and the World of the Classical Age and âthese traditions were combined⌠giving rise to new forms, partly because the ancient religion was always respected and tolerated by the conquerors.â[5] The cults of Isis and of Osiris spread and aspects of Egyptian Mystery religion may have influenced the development of Christian theology, some claim even the story of Jesus of Nazareth as it developed in various gospel accounts.[6]

Timeline

See also

Notes

- â Overy, 58

- â Sigmund Freud, Moses and Monotheism (NY: Vintage, 1959 (original, 1939), ISBN 978-0394700144).

- â âThe priests of Amen-Re and the Theban Kings: The growing power of the priesthood during the New Kingdomâ The priests of Amen-Re and the Theban Kings: the growing power of the priesthood during the New kingdom Retrieved February 15, 2008.

- â Agnese and Re, 22

- â Agnese and Re, 23

- â Richard Heinberg, âIn Search of the Historical Jesus,â New Dawn Magazine, No 50, September-October, 1998, In Search of the Historical Jesus Retrieved February 15, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Agnese, Giorgio and Re, Maurizio. Ancient Egypt: Art and Archeology of the Land of the Pharaohs. NY: Barnes & Noble, 2003. ISBN 9780760783801

- Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Scepter of Egypt The Hyksos Period and the New Kingdom. Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1990. ISBN 9780300091601

- Morris, Ellen Fowles. The Architecture of Imperialism Military Bases and the Evolution of Foreign Policy in Egypt's New Kingdom. Probleme der Ăgyptologie, 22. Bd. Leiden: Brill, 2005.

- Overy, Richard. The Times Complete Atlas of World History, 6th ed. NY: Barnes & Noble, 2004.

- Thomas, Susanna. Rameses II Pharaoh of the New Kingdom. Leaders of ancient Egypt. New York, N.Y.: Rosen Pub. Group, 2003. ISBN 9780823935970

- Warburton, David. State and Economy in Ancient Egypt: Fiscal Vocabulary of the New Kingdom. Orbis biblicus et orientalis, 151. Fribourg, Switzerland: University Press, 1997 ISBN 9783525537879

External links

All links retrieved November 11, 2022.

| |||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.