Orangutan

| Orangutans[1] | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| Simia pygmaeus Linnaeus, 1760 | ||||||||||||||

Orangutan distribution

| ||||||||||||||

|

Pongo pygmaeus |

Orangutan (also written orang-utan, orang utan, and orangutang) is any member of two species of great apes with long arms and reddish, sometimes brown, hair, native to Indonesia and Malaysia. Organgutans are the only extant (living) species in the genus Pongo and the subfamily Ponginae, although that subfamily also includes the extinct Gigantopithecus and Sivapithecus genera.

Orangutans are apes in the family Hominidae and superfamily Hominoidea (order Primates). Members of the Hominidae family, which include the gorillas, chimpanzees, orangutans, and humans, are known as the "great apes," while all other apes belong to the family Hylobatidae and are known as the "lesser apes" (gibbons).

In another taxonomic scheme, historically popular, the orangutans, chimpanzees, and gorillas are placed as members of the Pongidae family, while humans are separated into the Hominidae family. Some researchers place gorillas and chimpanzees (and the related bonobos) into the Panidae family, while orangutans remain in the Pongidae family, and humans in the Hominidae family.

The orangutan name derives from the Malay and Indonesian phrase orang hutan, meaning "person of the forest."[2]

Orangutans are remarkably similar to humans in anatomy and physiology, and even show evidence of socially transmitted behaviors (see cultural aspects). Of course, the differences between humans and orangutans are striking in terms of other aspects by which humans define themselves: social, religious, cultural, spiritual, mental, and psychological aspects.

Orangutans are the most arboreal of the great apes, spending nearly all of their time in the trees, making new nests in the trees every night. Today, they are endangered and only found in rainforests on the islands of Borneo and Sumatra. Borneo is the third-largest island in the world and is divided between Indonesia, Malaysia, and Brunei. Sumatra is the sixth-largest island in the world and is entirely in Indonesia. Orangutan fossils have been found in Java, Vietnam, and China. It is felt that 10,000 years ago orangutans ranged throughout Southeast Asia, including southern China, and numbered perhaps in the hundreds of thousands, but now together the two species may be less than 60,000 individuals.[3]

Characteristics, behavior and language

Adult orangutan males are about 4.5 feet (1.4 m) tall and up to 180 pounds (82 kg) in weight. They are primarily diurnal, with most of their time spent in trees, traveling from branch to branch. At night, they usually make a new nest for sleeping constructed from branches and built 15 to 100 feet up in a tree.[4] They primarily eat fruit, leaves, flowers, bark, insects, honey, and vines.[5]

Orangutans are thought to be the sole fruit disperser for some plant species including the climber species Strychnos ignatii, which contains the toxic alkaloid strychnine.[6] It does not appear to have any effect on orangutans except for excessive saliva production.

Like the other great apes, orangutans are remarkably intelligent. Although tool use among chimpanzees was documented by Jane Goodall in the 1960s, it wasn't until the mid-1990s that one population of orangutans was found to use feeding tools regularly. A 2003 paper in the journal Science described evidence for distinct orangutan cultures.[7] Orangutans have shown evidence of some socially learned traditions (such as using leaves as napkins to wipe leftover food from their chins) that appear to be passed down through generations, appearing in some orangutan groups but not others.[8]

The first orangutan language study program, directed by Dr. Francine Neago, was listed by Encyclopedia Britannica in 1988. The orangutan language project at the Smithsonian National Zoo in Washington, D.C., uses a computer system originally developed at the University of California, Los Angeles, by Neago in conjunction with IBM.[9]

Although orangutans are generally passive, aggression toward other orangutans is very common. They are solitary animals and can be fiercely territorial. Immature males will try to mate with any female, and may succeed in forcibly copulating with her if she is also immature and not strong enough to fend him off. Adult males are about twice the size of adult females. Mature females fend off their immature suitors, preferring to mate with a mature male. Females have their first offspring at 13 to 15 years of age.[10] Wild orangutans are known to visit human-run facilities for orphaned young orangutans released from illegal captivity, interacting with the orphans, and probably helping them adapt in their return to living in the wild.

Species and subspecies

Two species, Pongo pygmaeus (Borean orangutan) and Pongo abelii (Sumatran orangutan), are recognized, with Pongo pygmaeus divided into three populations. Originally both P. pygmaeus and P. abelii, which are on two different, isolated islands, were classified as subspecies, but they have since been elevated to full species level. The three populations on Borneo were elevated to subspecies.

- Genus Pongo [11]

- Bornean orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus)

- Pongo pygmaeus pygmaeus - northwest populations

- Pongo pygmaeus morio - northeast and east populations

- Pongo pygmaeus wurmbii - southwest populations

- Sumatran orangutan (P. abelii)

- Bornean orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus)

Some suggest that the subspecies wurmbii is conspecific with the Sumatra population (P. abelii).

In addition, a fossil species, Pongo hooijeri, is known from Vietnam, and multiple fossil subspecies have been described from several parts of southeastern Asia. It is unclear if these belong to P. pygmaeus or P. abeli, or, in fact, represent distinct species.

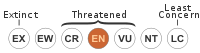

Conservation status

The Borneo species of orangutans is highly endangered, and the Sumatra species is critically endangered, according to the IUCN Red List of Mammals. Both species are listed on Appendix I of CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora). The Borneo population is estimated at about 50,000 in the wild, while the Sumatran species is estimated at 7,000‚Äď7,500 individuals.

Orangutan habitat destruction due to logging, mining, and forest fires has been increasing rapidly in the last decade.[12] A major factor in that period of time has been the conversion of vast areas of tropical forest to oil palm plantations, for the production of palm oil.[13] Much of this activity is illegal, occurring in national parks that are officially off-limits to loggers, miners, and plantation development. There is also a major problem with the poaching of baby orangutans for sale in the pet trade.

Major conservation centers in Indonesia include those at Tanjung Puting in Central Kalimantan (Borneo in Indonesia is referred to as Kalimantan), Kutai in East Kalimantan, Gunung Palung in West Kalimantan, and Bukit Lawang in the Gunung Leuser National Park on the border of Aceh and North Sumatra. In Malaysia, conservation areas include Semenggok in Sarawak, and the Sepilok Orang Utan Sanctuary near Sandakan in Sabah.

Etymology

The word orangutan is derived from the Malay (the language of Malaysia) and Indonesian words orang, meaning "person," and hutan, meaning "forest," thus "person of the forest." Orang Hutan is the common term in these two national languages, although local peoples may also refer to them by local languages. Maias and mawas are also used in Malay, but it is unclear if those words refer only to orangutans, or to all apes in general.

The word was first attested in English in 1691 in the form orang-outang, and variants with -ng instead of -n, as in the Malay original, are found in many languages. This spelling (and pronunciation) has remained in use in English up to the present, but has come to be regarded as incorrect by some.[14] However, dictionaries such as the American Heritage Dictionary regard forms with -ng as acceptable variants.

The name of the genus Pongo comes from a sixteenth-century account by Andrew Battell, an English sailor held prisoner by the Portuguese in "Angola" (probably somewhere near the mouth of the Congo River). He describes two anthropoid "monsters" named Pongo and Engeco. It is now believed that he was describing gorillas, but in the late eighteenth century it was believed that all great apes were orangutans; hence Lacépède's use of Pongo for the genus.[15]

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ C. Groves, ‚ÄúOrder Primates, Order Monotremata, (and selected other orders,‚ÄĚ in Mammal Species of the World, 3rd ed., ed. D. E. Wilson and D. M. Reeder (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005 ISBN 0801882214), 183‚Äď184.

- ‚ÜĎ Orangutan Foundation International, All about orangutans, 2005; Public Library of Science, Tracking orangutans from the sky, PLoS Biol 3, no. 1 (2005): e22. Retrieved February 6, 2007.

- ‚ÜĎ Orangutan Foundation International, All about orangutans, 2005. Retrieved February 6, 2007.

- ‚ÜĎ Ibid.

- ‚ÜĎ Ibid.

- ‚ÜĎ H. D. Rijksen, ‚ÄúA field study on Sumatran orang utans (Pongo pygmaeus abelii, Lesson 1827): Ecology, behaviour and conservation,‚ÄĚ Quarterly Review of Biology 53 (1978).

- ‚ÜĎ C. P. van Schaik, M. Ancrenaz, G. Borgen, B. Galdikas, C. D. Knott, I. Singleton, A. Suzuki, S. S. Utami, and M. Merrill, ‚ÄúOrangutan cultures and the evolution of material culture,‚ÄĚ Science 299, no. 5603 (2003): 102‚Äď105.

- ‚ÜĎ Orangutan Foundation International, All about orangutans, 2005. Retrieved February 6, 2007.

- ‚ÜĎ Smithsonian National Zoological Park and Friends of the National Zoo, Orang utan language project, 2007. Retrieved February 6, 2007.

- ‚ÜĎ Orangutan Foundation International, All about orangutans, 2005. Retrieved February 6, 2007.

- ‚ÜĎ C. Groves, ‚ÄúOrder Primates, Order Monotremata, (and selected other orders,‚ÄĚ in Mammal Species of the World, 3rd ed., ed. D. E. Wilson and D. M. Reeder (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005 ISBN 0801882214), 183‚Äď184.

- ‚ÜĎ H. D. Rijksen and E. Meijaard, Our Vanishing Relative: The Status of Wild Orang-utans at the Close of the Twentieth Century (Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1999).

- ‚ÜĎ Helen Buckland, The oil for ape scandal: How palm oil is threatening the orang-utan, ed. Ed Matthew (Friends of the Earth Trust). Retrieved May 21, 2007.

- ‚ÜĎ Alpha Dictionary, Orangutan. Retrieved December 20, 2006.

- ‚ÜĎ C. Groves, A history of gorilla taxonomy, in Gorilla Biology: A Multidisciplinary Perspective, ed. A. B. Taylor and M. L. Goldsmith (Cambridge University Press, 2002), 15‚Äď34. Retrieved May 21, 2007.

External links

All links retrieved November 17, 2022.

- Primate Info Net Pongo Factsheet

- The Borneo Orangutan Survival Foundation

- The Borneo Orangutan Survival Foundation (BOS) ‚Äď Australia.

- Save the Orangutan Part of a worldwide group dedicated to saving and preserving orangutans in Borneo.

- WWF Heart of Borneo conservation initiative - The WWF's information about the Heart of Borneo‚ÄĒ220,000 km¬≤ of upland tropical rainforest, where endangered species such as the orang-utan, rhinoceros, and pygmy elephant cling for survival.

- Sumatran Orangutan Society international non-profit organization dedicated to the protection of Sumatran orangutans.

- Sumatra Orangutan Conservation Programme a program under PanEco which reintroduces captured orangutans in the wilds among many other projects in Sumatra.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.