Hookworm

| Necator americanus | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

|

Species Necator americanus |

A hookworm is any of a number of small, parasitic nematodes (roundworms) of the order Strongiloidae and family Ancylostomatidae that have hooked mouthparts to attach themselves to the intestine wall of the host.

Hookworms are thought to infect 800 million people worldwide and possibly up to one-fifth of the world's population. Ancylostoma and Necator are two genera of hookworms that are particularly widespread, and Necator causes about 90 percent of tropical and semitropical infestations (Towle 1989). The species Necator americanus predominates in the Americas, Sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia, China, and Indonesia, while the species Ancylostoma duodenale predominates in the Middle East, North Africa, India and (formerly) in southern Europe.

Ancylostoma braziliense and Ancylostoma tubaeforme species infect cats, while Ancylostoma caninum infects dogs. Uncinaria stenocephala infects both dogs and cats.

Personal responsibility plays an important role in preventing hookworm infections. Ancyostoma and Necator enter through the feet, and thus wearing shoes in likely areas harboring the larva can protect against infestations, as can measures such as not using raw sewage for fertilizer, practicing good hygiene, and checking pets for diseases.

Hookworm infection is known by the name Ancylostomiasis, alternatively spelled ankylostomiasis and also called helminthiasis, miners' anemia, tunnel disease, brickmaker's anemia, Egyptian chlorosis, and in Germany Wurmkrankheit. It is caused when hookworms, present in large numbers, produce an iron deficiency anemia by voraciously sucking blood from the host's intestinal walls. Hookworm infection is rarely fatal, but anemia can be significant in the heavily infected individual.

Hookworms are leading causes of maternal and child morbidity in the developing countries of the tropics and subtropics. In susceptible children, hookworms cause intellectual, cognitive, and growth retardation, intrauterine growth retardation, prematurity, and low birth weight among newborns born to infected mothers.

Overview

Hookworms are a group within the nematodes or roundworms (phylum Nematoda). Nematodes are one of the most common phyla of animals, with over 20,000 different described species.

Like other nematodes, hookworms have bodies that are long and slender and taper at both ends. While think and round in cross section, they are actually bilaterally symmetric. Adult females of A. duodenale are from 10 to 13 mm and males are 8-11 mm; adult females of N. americanus are 9 to 11 mm, while A. duodenale are from 7 to 9mm (CDC 2007).

Like other nematodes, hookworms have a complete digestive system, with a separate orifice for food intake and waste excretion. The pseudocoelom body cavity lacks the muscles of coelomate animals that force food down the digestive tract and thus depend on internal/external pressures and body movement to move food through their digestive tracts. They have no circulatory or respiratory systems, so they use diffusion to breathe and for circulation of substances around their body.

Hookworm epidermis secretes a layered cuticle made of keratin that protects the body from drying out, from digestive juices, or from other harsh environments. Because it is inelastic and does not allow the volume of the hookworm to increase, the worm has to molt and form new cuticles. The larval stages are designated L1 to the L5 (adult).

Hookworms require a moist, fairly cool environment to survive usually within 17-30 oC.

Hookworms are much smaller than the large roundworm, Ascaris lumbricoides, and the complications of tissue migration and mechanical obstruction so frequently observed with roundworm infestation are less frequent in hookworm infestation. The most significant risk of hookworm infection is anemia, secondary to loss of iron (and protein) in the gut. The worms suck blood voraciously and damage the mucosa. However, the blood loss in the stools is occult blood loss (not visibly apparent).

Hookworm is commonly called "larva migratoria" in Spanish and "bicho do pé" in Portuguese.

Life cycle

The free living stage of the hookworms thrive in warm earth where temperatures are over 18°C. They exist primarily in sandy or loamy soil and cannot live in clay or muck. Rainfall averages must be more than 1000 mm (40 inches) a year. Only if these conditions exist can the eggs hatch.

Hookworm larval stages are designated L1 to L5, with L5 being the adult. In most nematodes, it is the L3 larvae that is the infective form (Stewart 1998). For example, in Necator americanus (hookworm in people), Ancylostoma duodenale (hookworm in humans), A. caninum (hookworm in dogs), and A. braziliense (hookworm in dogs), it is the L3 larvae that is invasive (Stewart 1998).

The typical life cycle is as follows. Eggs are passed in the feces and under favorable conditions larvae hatch in one to two days (CDC 2007). They grow in the feces and/or the soil, and after two molts (five to ten days) they become filariform (third-stage) larvae that are infective (CDC 2007). These filariform larvae can survive three to four weeks in good environmental conditions, and upon contact with the host, they penetrate the skin (CDC 2007).

At the L3 stage and later, as maturation to the adult parasite occurs, all species undergo a migration within the body of the definitive host, usually via the bloodstream or lymphatic system to the heart, lungs, trachea, and then to the intestine (Stewart 1998). During their migration, when they have transported from the heart to the lung, they penetrate the pulmonary alveoli, ascend into the pharynx, and are swallowed (CDC 2007). When they reach the small intestine, they attach to the wall and utilize the blood. The parasite produces thin walled eggs that leave the definitive host in the feces to begin the cycle again (Stewart 1998). Most adult worms are eliminated in one to two years, although some reach several years (CDC 2007).

It is possible that the worm does not immediately produce eggs, but does cause anemia. Diagnosis is more difficult during this latent stage.

Some infection by A. duodenale may occur by the oral route and via the mammary glands, but A. americanus requires a transpulmonary migration phase (CDC 2007).

History

The symptoms now attributed to hookworm appear in papyrus papers of ancient Egypt (c. 1600 B.C.E.), described as a derangement characterized by anemia. Avicenna, a Persian physician of the eleventh century, discovered the worm in several of his patients and related it to their disease. In later times, the condition was noticeably prevalent in the mining industry in England, France, Germany, Belgium, North Queensland, and elsewhere.

Italian physician Angelo Dubini was the modern-day discoverer of the worm in 1838 after an autopsy of a peasant woman. Dubini published details in 1843 and identified the species as Ancylostoma duodenale.

Working in the Egyptian medical system in 1852, German physician Theodor Bilharz, drawing upon the work of colleague Wilhelm Griesinger, found these worms during autopsies and went a step further in linking them to local endemic occurrences of chlorosis, which would probably be called iron deficiency anemia today. The disease was linked to nematoid worms (Ankylostoma duodenalis) from one-third to half an inch long in the intestine chiefly through the labors of Bilharz and Griesinger.

A breakthrough came 25 years later following a diarrhea and anemia epidemic that took place among Italian workmen employed on the Gotthard Rail Tunnel. In an 1880 paper, physicians Camillo Bozzolo, Edoardo Perroncito, and Luigi Pagliani correctly hypothesized that hookworm was linked to the fact that workers were forced to defecate inside the 15 km tunnel, and that many wore worn-out shoes.

In 1897, it was established that the skin was the principal avenue of infection and the biological life cycle of the hookworm was clarified. In 1899, American zoologist Charles Wardell Stiles brought this evidence to bear on health issues in the southeast United States, identifying "progressive pernicious anemia" seen in the southern United States was caused by A. duodenale, and he also identified the other important hookworm species: U. Necator. Indeed, testing in the 1900s revealed very heavy infestations in school age children.

On October 26, 1909, the Rockefeller Sanitary Commission for the Eradication of Hookworm Disease was organized as a result of a gift of US $1 million from John D. Rockefeller, Sr. Though humanitarian reasons are cited, some speculate that the motive was to open markets in the Appalachian region by creating more disposable income. Regardless, the five-year program was a remarkable success and a great contribution to United States public health, instilling public education, medication, field work, and modern government health departments in eleven southern states. The hookworm exhibit was a prominent part of the 1910 Mississippi State Fair. The program nearly eradicated hookworm. The program would flourish afterward with new funding as the Rockefeller Foundation International Health Division.

In the 1920s, hookworm eradication reached the Caribbean and Latin America, where great mortality was reported among blacks in the West Indies towards the end of the eighteenth century, as well as through descriptions sent from Brazil and various other tropical and sub-tropical regions.

Early treatment was with thymol to kill the worms, followed by epsom salt to clear the body of the worms. Later on, tetrachloroethylene was the leading method. It was not until later in the mid-twentieth century when new organic drug compounds were developed.

Pathology

Most individuals with hookworm infection are asymptomatic (without symptoms). Only very high loads of the parasite or poor nutrition combined with infection lead to anemia.

The symptoms are pain in the stomach, capricious appetite, pica (or dirt-eating), obstinate constipation followed by diarrhea, palpitations, small and unsteady pulse, coldness of the skin, pallor of the skin and mucous membranes, diminution of the secretions, loss of strength and, in cases running a fatal course, dysentery, hemorrhages, and edema (swelling of any organ or tissue due to accumulation of excess lymph fluid).

In contrast with most intestinal helminthiases that concentrate parasitic load in children, hookworm prevalence is often higher among adult males. In tropical areas, this is associated with high prevalence of anemia among adult men.

Prevention

The main lines of precaution are those dictated by sanitary science:

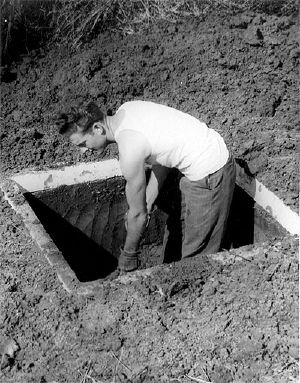

- Prevent skin/soil contact: do not walk barefoot.

- Do not defecate outside latrines, toilets, and so forth.

- Do not use human excrement or raw sewage as manure/fertilizer in agriculture.

- Worm pet dogs—canine hookworms cannot develop to adulthood in humans, but can cause an unpleasant rash called cutaneous larva migrans.

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, many people in Mississippi in the United States were plagued by hookworms. They did not have indoor plumbing or proper sanitation facilities. As a result, hookworms from feces and other sources were very prevalent (as well as other diseases caused by lack of sanitation).

Diagnosis

To infected persons who have walked outside in soil infested with hookworms, mosquito-like "bites" on the sole of the foot may indicate hookworm entry. They also commonly appear on the hands if the person has been handling dirt. On the second day, the "bites" turn into lines and medical attention is advised.

People infected with hookworms often experience low energy. Coughing, wheezing, and fever will develop in the victim, sometimes as the larva travel to the lungs. Stomach pains, yellow skin, feet that go to sleep, head and joint aches, weakness, vomiting, constipation, and diarrhea are other common symptoms. Very common visible symptoms include a pot belly and angel's wings: shoulder blades that are extended forward, because of the person's slumped, emaciated body. In severe cases, blurred vision and a fish-eye stare have been reported.

The mainstay of diagnosis is to detect the worm eggs on microscopal examination of the stools, but this may not be possible when the worm does not immediately produce eggs.

Sometimes larvae can be seen in an older feces sample at room temperature.

Treatment

Hookworm can be treated with local cryotherapy (use of cold temperatures) when it is still in the skin.

Albendazole is effective both in the intestinal stage and during the stage the parasite is still migrating under the skin.

In case of anemia, iron supplementation can cause relief symptoms of iron deficiency anemia. However, as red blood cell levels are restored, shortage of other essentials, such as folic acid or vitamin B12, may develop, so this might also be supplemented.

Beneficial aspects of hookworm infections

Moderate hookworm infections have been demonstrated to have beneficial effects on their hosts. Research has demonstrated that people with moderate hookworm infections are half as likely to experience asthma (BBC 2001) or hay fever (BBC 2003).

The theory is that our immune systems evolved under constant assault from a variety of parasites, most of which have to modulate our immune response to succeed. That is, they have to regulate down the response that would otherwise attack them. Evolving with a down-regulated immune system means that in the absence of those down-regulating parasites our immune systems often attack our own tissues, leading to asthma, hay fever, IBD, colitis, Crohn's and perhaps other autoimmune diseases. Hence the increase in autoimmune diseases in the relatively clean and sterile industrialized world. (See allergy article.)

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

- Albanese, G., C. Venturi, and G. Galbiati. 2001. Treatment of larva migrans cutanea (creeping eruption): a comparison between albendazole and traditional therapy. Int J Dermatol 40(1): 67-71

- BBC Health Eat worms - feel better. BBC. Retrieved February 8, 2007.

- BBC Health Worm infestation 'beats asthma' BBC. Retrieved February 8, 2007.

- CDC. 2007. Hookworm. DPDx: Laboratory Identification of Parasites of Public Health Concern. Retrieved February 8, 2007.

- Hotez, P., and D. Pritchard. 1995. Hookworm infection. Sci Am June: 68-74

- Stewart, T. 1998. Detailed taxonomy of the parasitic helminths. Cam. University Schistosome Research Group.

- Towle, A. 1989. Modern Biology. Austin, TX: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. ISBN 0030139198.

External links

All links retrieved January 13, 2018.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.