Difference between revisions of "History of Christianity" - New World Encyclopedia

David Doose (talk | contribs) m (→History) |

|||

| (175 intermediate revisions by 8 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{approved}}{{images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Paid}}{{Copyedited}} |

{{Christianity}} | {{Christianity}} | ||

| − | |||

| − | Christianity | + | The '''history of Christianity''' concerns the history of the [[Christianity|Christian]] [[religion]] and the [[Church (disambiguation)|Church]], from [[Jesus]] and his [[Twelve Apostles]] and [[Seventy Disciples]] to contemporary times. Christianity is the [[monotheism#Christian view|monotheistic]] religion which considers itself based on the revelation of Jesus Christ. In many [[Christian denominations]] "The Church" is understood [[Theology|theologically]] as the institution founded by Jesus for the [[salvation]] of humankind. This understanding is sometimes called [[High Church]]. In contrast, [[Low Church]] denominations generally emphasize the personal relationship between a believer and Jesus Christ. |

| − | + | Christianity began in first century C.E. [[Jerusalem]] as a [[Jewish]] sect, but quickly spread throughout the [[Roman Empire]] and beyond to countries such as [[Ethiopia]], [[Armenia]], [[Mirian III of Iberia|Georgia]], [[Assyria]], [[Iran]], [[India]], and [[China]]. Although it was originally [[Persecution|persecuted]], it would ultimately become the [[state religion]] of the Roman Empire in 380 C.E. During the [[Age of Exploration]], Christianity expanded throughout the world, becoming the world's largest religion.<ref> [http://www.adherents.com/Religions_By_Adherents.html Number of Adherents]. ''Adherents.com''. Retrieved November 24, 2019.</ref> | |

| − | + | Throughout its history, the religion has weathered [[schism]]s and theological disputes that have resulted in many distinct Churches. The two largest Churches are the [[Roman Catholic Church]] and the [[Eastern Orthodox Church]], but the various other [[Eastern Christianity|Eastern Churches]] (such as [[Oriental Orthodoxy]]), [[Protestant|Protestant Churches]] (such as [[Lutheranism]]) and others represent a large portion of the Christian community as well. | |

| − | + | {{toc}} | |

| − | + | As Christianity moves into the twenty-first century significant efforts have been made to reconcile the schism between the Catholic Church and the [[Eastern Orthodox Church]]es, between Catholicism and Protestantism and between all the Protestant denominations. | |

| − | + | ==Life of Jesus (2–8 B.C.E..E. to 29–36 C.E.) == | |

| − | + | [[Image:Christus Ravenna Mosaic.jpg|thumb|255px|right|Jesus Christ, [[Christ Pantocrator]]]] | |

| − | + | Though the life of [[Jesus]] is a matter of academic debate, scholars<ref>Robert E. Van Voorst, ''Jesus Outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence'' (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans, ISBN 978-0802843685), 16.</ref> generally agree on the following basic points: Jesus was born ca. 4 B.C.E. and grew up in [[Nazareth]] in [[Galilee]]; his ministry included recruiting [[disciples]], who regarded him as a [[miracle]]worker, [[Exorcism|exorcist]], and [[Healing|healer]]; he was executed by [[crucifixion]] in [[Jerusalem]] ca. 33 C.E.. on orders of the [[Roman governor|Roman Governor]] of [[Iudaea Province]], [[Pontius Pilate]];<ref>R.E. Brown, ''The Death of the Messiah: From Gethsemane to the Grave'' (New York: Doubleday, Anchor Bible Reference Library, 1994), 964; S.J.D. Cohen, ''From the Maccabees to the Mishnah'' (Westminster Press, 1987), 78, 93, 105, 108; Michael Grant, ''Jesus, An Historian's View of the Gospels'' (New York: Scribner's, 1977), 34–35, 78, 166, 200; Paula Fredriksen, ''Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews'' (Pan Books, 2000, ISBN 0333783131), 6–7, 105–110, 232–234, 266; John P. Meier, ''A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus'' vol. 1 ''The Roots of the Problem and the Person'' (Doubleday, 1991), 68, 146, 199, 278, 386, and vol. 2, 726; Geza Vermes, ''Jesus the Jew'' (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1973), 37; P. L. Maier, ''In the Fullness of Time'' (Kregel, 1991), 1, 99, 121, 171; N.T. Wright, ''The Meaning of Jesus: Two Visions'' (HarperCollins, 1998), 32, 83, 100–102, 222; L.T. Johnson, ''The Real Jesus'' (San Francisco: Harper San Francisco, 1996), 123; Rudolf Bultmann, ''Jesus'' (Berlin: Deutsche Bibliothek, 1926), 159.</ref> and after his [[crucifixion]],<ref>on death by crucifixion, see L.T. Johnson, ''The Real Jesus'' (San Francisco: Harper San Francisco, 1996); John P. Meier, "The Circle of the Twelve: Did It Exist during Jesus' Public Ministry?" in ''Journal of Biblical Literature'' 116 (1997): 664–665.</ref> Jesus was [[Joseph of Arimathea|buried in a tomb]].<ref>R.E. Brown, ''Death of the Messiah'' vol. 2 (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1994), 1240–1241; J.A.T. Robinson, ''The Human Face of God'' (Philadelphia: Westminster, 1973), 131; Bart Ehrman, ''From Jesus to Constantine: A History of Early Christianity'' (The Teaching Company, 2003), lecture 4, "Oral and Written Traditions About Jesus" (audiotape); M. J. Borg and N. T. Wright, ''The Meaning of Jesus'' (San Francisco: Harper Collins, 1999), 12; G. Habermas, ''The Historical Jesus'' (College Press, 1996), 128.</ref> Some have argued for the historicity of the [[empty tomb]] story<ref>Michael Grant, ''Jesus: An Historian's Review of the Gospels'' (New York: Scribner's 1977), 176; P.L. Maier, "The Empty Tomb as History" in ''Christianity Today'' (March 1975): 5; William Craig, "The Guard at the Tomb," in ''New Testament Studies'' 30 (1984): 273–281; W. Craig, "The Historicity of the Empty Tomb of Jesus," in ''New Testament Studies'' 31 (1985): 39–67.</ref> and Jesus' [[Resurrection appearances of Jesus|resurrection appearances]].<ref>Robert H. Gundry, ''Soma in Biblical Theology: With Emphasis on Pauline Anthropology'' (Society for New Testament Studies Monograph Series) (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1976).</ref> The resurrection of Jesus formed the basis and impetus of the Christian faith.<ref>Johnson, 1996, 136; Gerd Ludemann, ''What Really Happened to Jesus?'' trans. J. Bowden (Louisville, Kentucky: Westminster John Knox Press, 1995), 80; N.T. Wright, "The New Unimproved Jesus," in ''Christianity Today'' (September 13, 1993): 26.</ref> It is claimed in the [[Bible]] that after Christ's [[resurrection]], he appeared to the disciples in Galilee and Jerusalem and was on the earth for 40 days before his [[Ascension]] to [[heaven]].<ref name="Oneplace.com">J.W. McGarvey, [https://www.christianity.com/church/church-history/jesus-christs-life-key-events-11542555.html Jesus Christ's Life: Key Events] ''christianity.com''. Retrieved November 24, 2019.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | The main sources of information regarding Jesus' life and teachings are the [[Gospels#Canonical Gospels|four canonical Gospels]] and to a lesser extent the [[Pauline epistles|writings of Paul]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | == | + | ==Early Christianity (33 – 325 C.E.)== |

| − | + | {{main|Early Christianity}} | |

| − | + | Early Christianity refers to the period when the religion spread in the Greco-Roman world and beyond, from its beginnings as a first century [[Judaism|Jewish]] sect,<ref>{{nkjv|Acts|3:1|Acts 3:1}}; {{nkjv|Acts|5:27–42|Acts 5:27–42}}; {{nkjv|Acts|21:18–26|Acts 21:18–26}}; {{nkjv|Acts|24:5|Acts 24:5}}; {{nkjv|Acts|24:14|Acts 24:14}}; {{nkjv|Acts|28:22|Acts 28:22}}; {{nkjv|Romans|1:16|Romans 1:16}}; Tacitus, ''Annales'' xv 44; Josephus. ''Antiquities'' xviii 3; Mortimer Chambers, et al. ''The Western Experience Volume II.'' chapter 5 (McGraw-Hill, 2006) ; ''The Oxford Dictionary of the Jewish Religion'' (Oxford University Press, USA, 1997, ISBN 0195086058), 158.</ref> to the end of the imperial persecution of Christians after the ascension of [[Constantine the Great]] in 313 C.E., to the [[First Council of Nicaea]] in 325. It may be divided into two distinct phases: the [[apostolic period]], when the first apostles were alive and organizing the Church, and the [[post-apostolic period]], when an early episcopal structure developed, whereby bishoprics were governed by [[bishops]] (overseers) via [[apostolic succession]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ===Apostolic Church=== | |

| + | {{main|Apostolic Age}} | ||

| + | The Apostolic Church, or [[Primitive Church]], was the community led by Jesus' [[Twelve Apostles|apostles]] and his relatives.<ref>Richard Gerberding and J. H. Moran Cruz, ''Medieval Worlds'' (New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2004), 51.</ref> According to the [[Great Commission]], the resurrected Jesus commanded the apostles to spread his teachings to all the world. The principal source of information for this period is the ''[[Acts of the Apostles]],'' which gives a history of the Church from the ''Great Commission'' ({{bibleverse||Acts|1:3-11}}) and [[Pentecost]] ({{bibleverse||Acts|2}}) and the establishment of the [[Orthodox Patriarch of Jerusalem#Bishops of Jerusalem|Jerusalem Church]] to the spread of the religion among the [[gentile]]s ({{bibleverse||Acts|10}}) and [[Paul of Tarsus|Paul's]] conversion ({{bibleverse||Acts|9}}) and eventual imprisonment (house arrest: {{bibleverse||Acts|28:30–31}}) in [[Rome]] in the mid-first century. However, the accuracy of ''Acts'' is also disputed and may conflict with accounts in the [[Epistles of Paul]].<ref> "Nevertheless this well-proved truth has been contradicted. Baur, Schwanbeck, De Wette, Davidson, Mayerhoff, Schleiermacher, Bleek, Krenkel, and others have opposed the authenticity of the Acts. An objection is drawn from the discrepancy between Acts ix, 19-28 and Gal., i, 17, 19. In the ''Epistle to the Galatians,'' i, 17, 18, Paul declares that, immediately after his conversion, he went away into Arabia, and again returned to Damascus. "Then after three years, I went up to Jerusalem to visit Cephas." In Acts no mention is made of Paul's journey into Arabia; and the journey to Jerusalem is placed immediately after the notice of Paul's preaching in the synagogues. Hilgenfeld, Wendt, Weizäcker, Weiss, and others allege here a contradiction between the writer of the ''Acts'' and Paul." [http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/01117a.htm Acts of the Apostles] ''Catholic Encyclopedia''. Retrieved November 25, 2019.</ref> | ||

| − | + | The first Christians were essentially all ethnically [[Jewish]] or Jewish [[Proselytes]]. Jesus preached to the Jewish people and called from them his first disciples, though the earliest documented "group" of appointed evangelizers, called the [[Seventy Disciples]], was not specifically ethnically Jewish. An early difficulty arose concerning Gentile (non-Jewish) converts. Some argued that they had to "become Jewish" (usually referring to [[circumcision]] and adherence to [[Kashrut|dietary law]]) before becoming Christian. The decision of [[Saint Peter|Peter]], as evidenced by conversion of the [[Centurion Cornelius]],<ref>"The baptism of Cornelius is an important event in the history of the Early Church. The gates of the Church, within which thus far only those who were circumcised and observed the Law of Moses had been admitted, were now thrown open to the uncircumcised Gentiles without the obligation of submitting to the Jewish ceremonial laws." [http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/04375b.htm Catholic Encyclopedia: Cornelius]. Retrieved November 25, 2019.</ref> was that they did not. The matter was further addressed with the [[Council of Jerusalem]]. | |

| − | The | + | The doctrines of the apostles brought the Early Church into conflict with some Jewish religious authorities, and this eventually led to the [[martyrdom]] of [[Saint Stephen|Stephen]] and [[James, son of Zebedee|James the Great]] and expulsion from the [[synagogue]]s. Thus, Christianity acquired an identity distinct from [[Rabbinic Judaism]]. The name "[[Christian]]" ([[Greek language|Greek]] {{polytonic|''Χριστιανός''}}) was first applied to the [[Disciple (Christianity)|disciples]] in [[Antioch]], as recorded in {{nkjv|Acts|11:26|Acts 11:26}}. |

| − | + | ====Worship of Jesus==== | |

| − | + | [[Image:Good shepherd 02b close.jpg|thumb|200px|left|Christ Jesus,<ref>"The figure (…) is an [[allegory]] of Christ as the shepherd" Andre Grabar, ''Christian iconography: a study of its origins'' (Princeton University Press, 1981, ISBN 0691018308).</ref> the ''Good Shepherd,'' third century.]] | |

| − | |||

| − | + | The sources for the beliefs of the apostolic community include the [[Gospels]] and [[New Testament]] [[Epistle]]s. The very earliest accounts are contained in these texts, such as early Christian creeds and [[hymns]], as well as accounts of the [[Passion (Christianity)|Passion]], the empty [[tomb]], and Resurrection appearances; often these are dated to within a decade or so of the [[crucifixion]] of Jesus, originating within the Jerusalem Church. | |

| − | + | The earliest Christian creeds and hymns express belief in the risen Jesus, e.g., that preserved in {{bibleverse||1Corinthians|15:3–4}} quoted by [[Saint Paul|Paul]]: ''"For what I received I passed on to you as of first importance: that Christ died for our sins according to the Scriptures, that he was buried, that he was raised on the third day according to the Scriptures."''<ref>Vernon H. Neufeld, ''The Earliest Christian Confessions'' (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1963), 47; Oscar Cullmann, ''The Earlychurch: Studies in Early Christian History and Theology,'' ed. A. J. B. Higgins (Philadelphia: Westminster, 1966), 64; Bultmann, ''Theology of the New Testament'' vol. 1, 45, 80–82, 293; R. E. Brown, ''The Virginal Conception and Bodily Resurrection of Jesus'' (New York: Paulist Press, 1973), 81, 92.</ref> The antiquity of the creed has been located by many scholars to less than a decade after Jesus' death, originating from the Jerusalem apostolic community,<ref>Wolfhart Pannenberg, ''Jesus–God and Man,'' translated Lewis Wilkins and Duane Pribe, (Philadelphia: Westminster, 1968), 90; Oscar Cullmann, ''The Early church: Studies in Early Christian History and Theology,'' ed. A. J. B. Higgins, (Philadelphia: Westminster, 1966), 66–66.</ref> No scholar dates it later than the 40s.<ref>Gerald O'Collins, ''What are They Saying About the Resurrection?'' (New York: Paulist Press, 1978), 112; on historical importance, cf. Hans von Campenhausen, "The Events of Easter and the Empty Tomb," in ''Tradition and Life in the Church'' (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1968), 44.</ref> Other relevant and very early creeds include {{bibleverse||1John|4:2}},<ref>Cullmann, 32.</ref> {{bibleverse||2Timothy|2:8}},<ref>Bultmann, ''Theology of the New Testament'' vol 1, 49, 81; Joachim Jeremias, ''The Eucharistic Words of Jesus,'' translated Norman Perrin (London: SCM Press, 1966), 102.</ref> {{bibleverse||Romans|1:3–4}},<ref>Pannenberg, 118, 283, 367; Neufeld, 1964, 7, 50.</ref> and {{bibleverse||1Timothy|3:16}}, an early creedal hymn.<ref>Reginald H. Fuller, ''The Foundations of New Testament Christology'' (New York: Scribner's, 1965), 214, 216, 227, 239; Neufeld, 1964, 7, 9, 128.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | == | + | ==== Jewish continuity ==== |

| − | + | Early Christianity retained many of the doctrines and practices of [[Judaism]]. They held the [[Tanakh|Jewish scriptures]] to be authoritative and sacred, employing mostly the [[Septuagint]] translation as the [[Old Testament]], and added other texts as the [[New Testament]] canon developed. Christianity also continued other Judaic practices: [[liturgy|liturgical]] worship, including the use of [incense]], an [[altar]], a set of scriptural readings adapted from [[synagogue]] practice, use of [[Religious music|sacred music]] in hymns and [[prayer]], and a [[Liturgical year|religious calendar]], as well as other distinctive features such as an exclusively male [[priest]]hood, and [[asceticism|ascetic]] practices ([[fasting]], etc.). | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The early Christians in first century believed [[Jehovah]] to be the Only true [[God]], the [[God#Biblical definition of God|God of Israel]], and considered Jesus to be the [[Messiah]] ([[Christ]]) prophesied in the [[Old Testament]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | === Post-Apostolic Church === | |

| + | {{seealso|Apostolic Fathers}} | ||

| + | [[Image:Lawrence-before-Valerianus.jpg|thumb|210px|right|[[Lawrence of Rome|St. Lawrence]] before [[Valerian (emperor)|Emperor Valerianus]] (martyred 258) by Fra Angelico]] | ||

| + | The post-apostolic period encompasses the time roughly after the death of the apostles when [[bishop]]s emerged as overseers of urban Christian populations, and continues during the time of persecutions until the legalization of Christian worship during the reign of [[Constantine the Great]]. The earliest recorded use of the terms ''[[Christianity]]'' (Greek {{polytonic|''Χριστιανισμός''}}) and ''[[Catholic]]'' (Greek {{polytonic|''καθολικός''}}), dates to this period, attributed to [[Ignatius of Antioch]] c. 107.<ref>Walter Bauer, ''Greek-English Lexicon''; Ignatius of Antioch, [http://www.earlychristianwritings.com/text/ignatius-magnesians-roberts.html Letter to the Magnesians] 10, [http://earlychristianwritings.com/text/ignatius-romans-lightfoot.html Letter to the Romans], [http://www.ccel.org/l/lake/fathers/ignatius-romans.htm Greek text]) Retrieved November 25, 2019. </ref> | ||

| − | == | + | ====Persecutions==== |

| − | + | From the beginning, Christians were subject to various [[persecution]]s. This involved even [[death]] for Christians such as [[Stephen]] ({{bibleverse||Acts|7:59}}) and [[James, son of Zebedee]] ({{bibleverse||Acts|12:2}}). Larger-scale persecutions followed at the hands of the authorities of the [[Roman Empire]], beginning in the year 64, when, as reported by the Roman historian [[Tacitus]], the [[Emperor Nero]] blamed Christians for that year's [[great Fire of Rome]]. | |

| − | + | According to Church tradition, it was under Nero's persecution that [[Saint Peter|Peter]] and [[Paul of Tarsus|Paul]] were each martyred in [[Rome]]. Similarly, several of the [[New Testament]] writings mention persecutions and stress the importance of endurance through them. For 250 years Christians suffered from sporadic [[Persecution of Christians|persecutions]] for their refusal to [[Imperial cult (Ancient Rome)|worship the Roman emperor]], which Rome considered [[treason]]ous and punishable by execution. In spite of these periodic persecutions, the Christian religion continued its spread throughout the [[Mediterranean Basin]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ====Ecclesiastical structure ==== | |

| + | By the late first and early second century, a hierarchical and episcopal structure became clearly visible; early bishops of importance were [[Pope Clement I|Clement of Rome]], [[Ignatius of Antioch]], [[Polycarp|Polycarp of Smyrna]], and [[Irenaeus|Irenaeus of Lyons]]. This structure was based on the doctrine of [[Apostolic Succession]] in which, by the ritual of the [[laying on of hands]], a bishop becomes the spiritual successor of the previous bishop in a line tracing back to the apostles themselves. Each Christian community also had [[presbyter]]s, as was the case with Jewish communities, who were also ordained and assisted the bishop; as Christianity spread, especially in rural areas, the presbyters exercised more responsibilities and took distinctive shape as [[priest]]s. Lastly, [[deacon]]s also performed certain duties, such as tending to the poor and sick. | ||

| − | + | ====Early Christian writings==== | |

| + | {{main|Ante-Nicene Fathers}} | ||

| + | As Christianity spread, its converts included members from well-educated circles of the [[Hellenism|Hellenistic]] world, some of whom became bishops. They produced two sorts of works: theological and "apologetic;" the latter were works aimed at defending the faith by using reason to refute arguments against the veracity of Christianity. These authors are known as the [[Church Fathers]], and study of them is called [[Patristics]]. Notable early Fathers include [[Ignatius of Antioch]], [[Polycarp]], [[Justin Martyr]], [[Irenaeus]], [[Tertullian]], and [[Clement of Alexandria]], [[Origen]] among others. | ||

| − | + | ==== Early [[iconography]] ==== | |

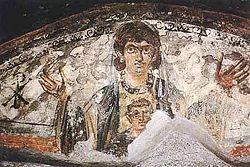

| + | [[Image:VirgenNino.jpg|thumb|250px|[[Virgin Mary|Virgin]] and Child. Wall painting from the early [[catacombs]], Rome, fourth century.]] | ||

| + | {{main|Christian art}} | ||

| + | Christian art emerged relatively late; the first known Christian images appeared from about 200 C.E. This early rejection of images, although never proclaimed by theologians, leaves us with little [[Archaeology|archaeological]] records regarding early Christianity and its development. The oldest Christian paintings are from the Roman [[Catacombs]], dated to about 200, and the oldest Christian [[sculpture]]s are from [[sarcophagi]], dating to the beginning of the third century.<ref>Grabar, 7</ref> | ||

| − | + | ====Early heresies==== | |

| + | The [[New Testament]] itself speaks of the importance of maintaining orthodox doctrine and refuting [[Heresy|heresies]], showing the antiquity of the concern.<ref>for example, {{bibleverse||2Corinthians|11:13–15}}; {{bibleverse||2Peter|2:1–17}}; {{bibleverse||2John|7–11}}; {{bibleverse||Jude|4–13}}, and the [[Epistle of James]] in general.</ref> Because of the [[Bible|biblical]] proscription against [[false prophet]]s (notably the Gospels of [[Gospel of Matthew|Matthew]] and [[Gospel of Mark|Mark]]) Christianity has always been preoccupied with the "correct," or ''[[orthodoxy|orthodox]],'' interpretation of the faith. Indeed, one of the main roles of the [[bishop]]s in the early Church was to determine the correct interpretations and refute contrarian opinions (referred to as ''heresy''). As there were differing opinions among the bishops, defining orthodoxy would consume the Church through the centuries (and still does, hence, "denominations"). | ||

| − | + | In his book ''[[Orthodoxy (book)|Orthodoxy]],'' [[Christian apologetics|Christian Apologist]] and writer [[G. K. Chesterton]] asserts that there have been substantial disagreements about [[faith]] from the time of the New Testament and [[Jesus of Nazareth|Jesus]]. He pointed out that the [[Twelve Apostles|Apostles]] all argued ''against'' changing the teachings of Christ as did the earliest [[Church Fathers|church fathers]] including [[Ignatius of Antioch]], [[Irenaeus]], [[Justin Martyr]] and [[Polycarp]] (see [[False prophets#New Testament|false prophet]], the [[antichrist]], the [[gnostic]] [[Nicolaitanes]] from the Book of Revelations and [[Man of Sin]]). Jesus also refers to false prophets ({{bibleverse||Mark|13:21–23|}}) and the "[[Lolium temulentum|darnel]]" ({{bibleverse||Matthew|13:25–30|}}, {{bibleverse||Matthew|13:36–43|}}) of the flock, warning that their distortion of the Christian faith should be rejected. | |

| − | + | The earliest controversies were generally [[Christology|Christological]] in nature; that is, they were related to Jesus' (eternal) [[Divine|divinity]] or [[Human|humanity]]. [[Docetism]] held that Jesus' humanity was merely an illusion, thus denying the incarnation. [[Arianism]] held that Jesus, while not merely mortal, was not eternally divine and was, therefore, separate from God, the Father. [[Trinitarianism]] held that [[God the Father]], [[Jesus the Son]], and the [[Holy Spirit]] were all strictly one being with three aspects. Many groups held [[dualism|dualistic]] beliefs, maintaining that reality was composed of two radically opposing parts: [[matter]], usually seen as [[evil]], and [[spirit]], seen as [[good]]. Others held that both the material and [[spiritual world]]s were created by God and were therefore both good, and that this was represented in the unified divine and human natures of Christ.<ref>Gerberding and Moran Cruz, 58</ref> | |

| − | + | The development of [[doctrine]], the position of orthodoxy, and the relationship between the various opinions is a matter of continuing academic debate. Since most Christians today subscribe to the doctrines established by the [[Nicene Creed]], modern Christian theologians tend to regard the early debates as a unified orthodox position against a minority of heretics. Other scholars, drawing upon, among other things, distinctions between [[Jewish Christians]], [[Pauline Christianity|Pauline Christians]], and other groups such as [[Gnosticism|Gnostics]] and [[Marcionite]]s, argue that [[early Christianity]] was fragmented, with contemporaneous competing orthodoxies.<ref>Walter Bauer, ''Orthodoxy and Heresy in Earliest Christianity'' (Fortress Press, 1979, ISBN 0800613635); Elaine Pagels, ''The Gnostic Gospels'' (Vintage; Reissue edition, 1989, ISBN 0679724532); Bart D. Ehrman, ''Lost Christianities: The Battles for Scripture and the Faiths We Never Knew'' (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003, ISBN 0195141830).</ref> | |

| − | + | ====Biblical canon==== | |

| + | {{seealso|Deuterocanonical books|Apocrypha|Antilegomena}} | ||

| + | [[Image:P46.jpg|thumb|175px|left|A folio from [[Papyrus 46|P46]], early third century New Testament manuscript useful in discerning the early Christian canon.]] | ||

| − | + | The Biblical [[canon]] is the set of books Christians regard as divinely inspired and thus constituting the Christian [[Bible]]. Though the Early Church used the [[Old Testament]] according to the canon of the [[Septuagint]] (LXX), the apostles did not otherwise leave a defined set of new [[scriptures]]; instead the [[New Testament]] developed over time. | |

| − | + | The writings attributed to the apostles circulated among the earliest Christian [[community|communities]]. The [[Pauline epistles]] were circulating in collected form by the end of the first century C.E. In the early second century, [[Justin Martyr]] mentions the "memoirs of the apostles," which Christians called "gospels" and which were regarded as on par with the Old Testament.<ref>Everett Ferguson, "Factors leading to the Selection and Closure of the New Testament Canon," in ''The Canon Debate,'' eds. L. M. McDonald & J. A. Sanders (Hendrickson, 2002), 302–303; cf. Justin Martyr, ''[[First Apology]]'' 67.3.</ref> A four gospel canon (the ''Tetramorph'') was in place by the time of [[Irenaeus]], c. 160, who refers to it directly.<ref>Ferguson, 301; cf. Irenaeus, ''[[On the Detection and Overthrow of the So-Called Gnosis|Adversus Haereses]]'' 3.11.8</ref> By the early third century, [[Origen]] may have been using the same 27 books as in the modern New Testament, though there were still disputes over the canonicity of ''[[Book of Hebrews|Hebrews]],'' ''[[Gospel of James|James]],'' ''[[II Peter]],'' ''II'' and ''III John,'' and ''[[Revelation]]''.<ref>Both points taken from Mark A. Noll's ''Turning Points'' (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 1997), 36–37.</ref> Likewise by 200 C.E. the [[Muratorian fragment]] shows that there existed a set of Christian writings somewhat similar to what is now the New Testament, which included the four gospels and argued against objections to them.<ref>H. J. De Jonge, "The New Testament Canon," in ''The Biblical Canons,'' eds. de Jonge & J. M. Auwers, (Leuven University Press, 2003), 315.</ref> Thus, while there was a good measure of debate in the Early Church over the New Testament canon, the major writings were accepted by almost all Christians by the middle of the second century.<ref>''The Cambridge History of the Bible,'' Volume 1, eds. P. R. Ackroyd and C. F. Evans, (Cambridge University Press, 1970), 308.</ref> | |

| − | Councils and | + | In his [[Easter]] letter of 367, [[Athanasius]], Bishop of Alexandria, gave a list of exactly the same books as what would become the [[New Testament]] canon,<ref>Carter Lindberg, ''A Brief History of Christianity'' (Blackwell Publishing, 2006, ISBN 1405110783), 15.</ref> and he used the word "canonized" ''(kanonizomena)'' in referring to them.<ref>David Brakke, "Canon Formation and Social Conflict in Fourth Century Egypt: Athanasius of Alexandria's Thirty Ninth Festal Letter," in ''Harvard Theological Review'' 87 (1994): 395–419.</ref> The [[Africa]]n [[Synod of Hippo]], in 393, approved the New Testament, as it stands today, together with the [[Septuagint]] books, a decision that was repeated by [[Councils of Carthage]] in 397 and 419. These councils were under the authority of [[Augustine of Hippo|St. Augustine]], who regarded the canon as already closed.<ref>Everett Ferguson, "Factors leading to the Selection and Closure of the New Testament Canon," in ''The Canon Debate,'' eds. L. M. McDonald & J. A. Sanders, (Hendrickson, 2002), 320; Frederick Fyvie Bruce, ''The Canon of Scripture'' (Intervarsity Press, 1988), 230; cf. Augustine, ''De Civitate Dei'' 22.8.</ref> Damasus's commissioning of the [[Latin Vulgate]] edition of the [[Bible]], c. 383, was instrumental in the fixation of the canon in the West.<ref>Bruce, 1988, 225.</ref> In 405, [[Pope Innocent I]] sent a list of the sacred books to a Gallic bishop, [[Exuperius|Exsuperius of Toulouse]]. When these bishops and councils spoke on the matter, however, they were not defining something new, but instead "were ratifying what had already become the mind of the Church."<ref>Ferguson, 2002, 320.</ref> Thus, from the fourth century, there existed unanimity in the West concerning the New Testament canon (as it is today), and by the fifth century the East, with a few exceptions, had come to accept the Book of Revelation and thus had come into harmony on the matter of the canon.<ref>''The Cambridge History of the Bible'' (volume 1), 1970, 305; [http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/03274a.htm Canon of the New Testament] ''Catholic Encyclopedia''. Retrieved November 25, 2019.</ref> Nonetheless, a full [[dogma]]tic articulation of the canon was not made until the [[Council of Trent]] of 1546 for [[Roman Catholic]]ism,<ref>[http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/03274a.htm Canon of the New Testament] ''Catholic Encyclopedia''. Retrieved November 25, 2019.</ref> the [[Thirty-Nine Articles]] of 1563 for the [[Church of England]], the [[Westminster Confession of Faith]] of 1647 for [[Calvinism]], and the [[Synod of Jerusalem]] of 1672 for the [[Greek Orthodox]]. |

| − | + | == Church of the Roman Empire (313–476) == | |

| + | [[Image:Spread of Christianity in Europe to AD 600.png|thumb|right|float|250px| | ||

| + | {{legend|#1F63A7|Spread of Christianity to 325 C.E.}} | ||

| + | {{legend|#6AB4FF|Spread of Christianity to 600 C.E.}}]] | ||

| + | Christianity in the period of Late Antiquity begins with the ascension of Constantine to the Emperorship of Rome in the early fourth century, and continues until the advent of the [[Middle Ages]]. The terminus of this period is variable because the transformation to the sub-Roman period was gradual and occurred at different times in different areas. It may generally be dated as lasting to the late sixth century and the reconquests of [[Justinian]], though a more traditional date is 476, the year that [[Romulus Augustus]], traditionally considered the last western emperor, was deposed. | ||

| − | + | ===Christianity legalized=== | |

| + | [[Galerius]] issued an edict permitting the practice of the Christian religion under his rule in April of 311.<ref>Lactantius, [http://www.ucalgary.ca/~vandersp/Courses/texts/lactant/lactpers.html#XXXIV ''De Mortibus Persecutorum''] ("On the Deaths of the Persecutors"), ch. 35–34. ''University of Calgary''. Retrieved November 25, 2019.</ref> In 313 [[Constantine I (emperor)|Constantine I]] and [[Licinius]] announced [[tolerance|toleration]] of Christianity in the [[Edict of Milan]]. Constantine would become the first Christian emperor. By 391, under the reign of [[Theodosius I]], Christianity had become the [[state religion]]. Constantine I, the first emperor to embrace Christianity, was also the first emperor to openly promote the newly legalized religion. | ||

| − | + | ===Constantine the Great=== | |

| + | [[Image:Constantine Musei Capitolini.jpg|thumb|200px|Head of Constantine's colossal statue at [[Musei Capitolini]]]] | ||

| + | {{seealso|Constantine I and Christianity}} | ||

| − | + | The Emperor [[Constantine I]] was exposed to Christianity by his mother, Helena. There is scholarly controversy, however, as to whether Constantine adopted his mother's humble Christianity in his youth, or whether he adopted it gradually over the course of his life.<ref name=Gerberding>Richard Gerberding and J. H. Moran Cruz, ''Medieval Worlds'' (New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2004), 55-56.</ref> | |

| − | Constantine | + | Christian sources record that Constantine experienced a dramatic event in 312 at the [[Battle of Milvian Bridge]], after which Constantine would claim the emperorship in the West. According to these sources, Constantine looked up to the [[sun]] before the battle and saw a [[Christian cross|cross]] of light above it, and with it the Greek words "''{{polytonic|Εν Τουτω Νικα}}''" ("by this, conquer!," often rendered in the [[Latin]] ''"[[in hoc signo vinces]]"''; Constantine commanded his troops to adorn their shields with a Christian symbol (the [[Labarum|Chi-Ro]]). Under this banner they were victorious.<ref>Gerberding and Moran Cruz, 55; cf. Eusebius, ''Life of Constantine''.</ref> How much Christianity Constantine adopted at this point is difficult to discern; most influential people in the empire, especially high military officials, were still [[Paganism|pagan]], and Constantine's rule exhibited at least a willingness to appease these factions. The Roman [[coin]]s minted up to eight years subsequent to the battle still bore the images of Roman gods. Nonetheless, the accession of Constantine was a turning point for the Christian Church. After his victory, Constantine supported the Church financially, built various [[basilica]]s, granted privileges (for example, exemption from certain [[tax]]es) to clergy, promoted Christians to high ranking offices, and returned property confiscated during the [[Great Persecution of Diocletian]].<ref name=Gerberding/> Between 324 and 330, Constantine built, virtually from scratch, a new imperial capital at [[Byzantium]] on the Bosphorus (it came to be named for him: [[Constantinople]]); the city employed overtly Christian [[architecture]], contained churches within the city walls (unlike "old" Rome), and had no pagan temples. In accordance with the prevailing customs, Constantine was [[baptism|baptized]] on his deathbed. |

| − | + | Constantine also played an active role in the leadership of the Church. In 313, he issued the [[Edict of Milan]], legalizing Christian worship. In 316, he acted as a judge in a [[North Africa]]n dispute concerning the [[Donatism|Donatist]] controversy. More significantly, in 325 he summoned the [[First Council of Nicaea|Council of Nicaea]], effectively the first [[Ecumenical Council]] (unless the [[Council of Jerusalem]] is so classified), to deal with the [[Arianism|Arian]] controversy. The Council would become more famous for their issue of the [[Nicene Creed]], which, among other things, professed a belief in ''One Holy Catholic Apostolic Church,'' the start of [[Christendom]]. The reign of Constantine established a precedent for the position of the Christian Emperor in the Church. [[Emperor]]s considered themselves responsible to God for the spiritual health of their subjects, and thus they had a duty of maintain orthodoxy.<ref name=Richards>Jeffrey Richards, ''The Popes and the Papacy in the Early Middle Ages 476–752.'' (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1979), 14–15.</ref> The emperor did not decide [[doctrine]]—that was the responsibility of the bishops—rather his role was to enforce doctrine, root out [[heresy]], and uphold ecclesiastical unity. The emperor ensured that God was properly worshiped in his empire; the exact nature of proper [[worship]] was left for the Church to determine. This precedent would continue until certain emperors of the fifth and six centuries sought to alter doctrine by imperial edict without recourse to councils, though Constantine's precedent generally remained the norm.<ref name=Richards/> | |

| − | + | The reign of Constantine did not represent a complete acceptance for Christianity in the empire, nor an end of persecution. His successor in the East, [[Constantius II]], kept Arian bishops at his court and installed them in various sees, expelling the orthodox bishops. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Constantius's successor, [[Julian the Apostate|Julian]], known in the Christian world as ''Julian the Apostate,'' was a [[Philosophy|philosopher]] who upon becoming emperor renounced Christianity and embraced a [[Neoplatonism|Neo-platonic]] and mystical form of [[paganism]], shocking the Christian establishment. Intent on re-establishing the prestige of the old pagan beliefs, he modified them to resemble Christian traditions such as the episcopal structure and public [[charity]] (hitherto unknown in Roman paganism). Julian eliminated most of the privileges and prestige previously afforded to the Christian Church as the official state religion. His reforms attempted to create a form of religious heterogeneity by, among other things, reopening pagan temples, accepting Christian bishops previously exiled as heretics, promoting [[Judaism]], and returning Church lands to their original owners. However, Julian's short reign ended when he died while campaigning in the East. | |

| − | + | Christianity came to dominance during the reign of Julian's successors, [[Jovian]], [[Valentinian I]], and [[Valens]]. On Feb. 27, 380, [[Theodosius I]] issued the edict ''De Fide Catolica'' establishing "Catholic Christianity"<ref>[http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/source/theodcodeXVI.html Theodosian Code] XVI.i.2, ''Medieval Sourcebook'': Banning of Other Religions by Paul Halsall, June 1997. Retrieved November 25, 2019.</ref> as the exclusive official [[state religion]], outlawed other faiths, and closed pagan temples.<ref>Gerberding and Moran Cruz, 57.</ref> Additional prohibitions were passed by Theodosius I in 391 further proscribing remaining pagan practices. | |

| − | + | ===Diocesan structure === | |

| + | After legalization, the Church adopted the same organizational boundaries as the Empire: geographical provinces, called [[diocese]]s, corresponding to imperial governmental territorial division. The bishops, who were located in major urban centers as per the pre-legalization tradition, oversaw each diocese. The bishop's location was his "seat," or "see"; among the sees, [[Pentarchy|five]] held special eminence: [[Rome]], [[Constantinople]], [[Jerusalem]], [[Antioch]], and [[Alexandria]]. The prestige of these sees depended in part on their apostolic founders, from whom the bishops were thus considered spiritual successors, e.g., St. Mark as founder of the See of Alexandria, St. Peter of the See of Rome, etc. There were other significant reasons for their priority. Jerusalem was the location of Christ's [[death]] and [[resurrection]] and the site of a first century council, among other things. Antioch was where Jesus' followers were first called Christians. Rome was where Saints Peter and Paul were [[Martyrdom|martyred]]. Constantinople was the "New Rome" where Constantine had moved his capital c. 330. In addition, all these cities had important relics. | ||

| − | + | === Papacy and primacy === | |

| + | {{main|Primacy of the Roman Pontiff}} | ||

| + | {{seealso|History of the Papacy}} | ||

| − | The | + | The [[Pope]] is the Bishop of Rome and the office is the "papacy." As a bishopric, its origin is consistent with the development of an episcopal structure in the first century. The papacy, however, also carries the notion of primacy: that the [[See of Rome]] is preeminent amongst all other sees. The origins of this concept are historically obscure; theologically, it is based on three ancient Christian traditions: (1) that the apostle Peter was preeminent among the apostles, see [[Primacy of Simon Peter]], (2) that Peter ordained his successors for the Roman See, and (3) that the bishops are the successors of the apostles ([[Apostolic Succession]]). As long as the [[Papal See]] also happened to be the capital of the Western Empire, the prestige of the Bishop of Rome could be taken for granted without the need of sophisticated theological argumentation beyond these points; after its shift to [[Milan]] and then [[Ravenna]], however, more detailed arguments were developed based on {{bibleverse||Matthew|16:18–19}} etc.<ref>Richards, 9</ref> Nonetheless, in antiquity the Petrine and Apostolic quality, as well as a "primacy of respect," concerning the Roman See went unchallenged by emperors, eastern patriarchs, and the Eastern Church alike.<ref>Richards, 10, 12</ref> The Ecumenical Council of Constantinople in 381 affirmed the primacy of Rome. Though the appellate jurisdiction of the Pope, and the position of Constantinople, would require further doctrinal clarification, by the close of Antiquity the primacy of Rome and the sophisticated theological arguments supporting it were fully developed. Just what exactly was entailed in this primacy, and its being exercised, would become a matter of controversy at certain later times. |

| − | + | === Ecumenical Councils === | |

| + | {{main|Nicene Christianity}} | ||

| + | During this era, several [[Ecumenical Council]]s were convened. These were mostly concerned with [[Christology|Christological]] disputes. The two Councils of Nicaea (325, 382) condemned Arian teachings as heresy and produced a creed (see [[Nicene Creed]]). The [[Council of Ephesus]] condemned [[Nestorianism]] and affirmed the [[Blessed Virgin Mary]] to be [[Theotokos]] ("God-bearer" or "Mother of God"). Perhaps the most significant council was the [[Council of Chalcedon]] that affirmed that Christ had two natures, fully God and fully man, distinct yet always in perfect union. This was based largely on [[Pope Leo I|Pope Leo the Great]]'s ''Tome''. Thus, it condemned [[Monophysitism]] and would be influential in refuting [[Monothelitism]]. However, not all denominations accepted all the councils, for example Nestorianism and the [[Assyrian Church of the East]] split over the Council of Ephesus of 431, [[Oriental Orthodoxy]] split over the Council of Chalcedon of 451, [[Pope Sergius I]] rejected the [[Quinisext Council]] of 692, and the [[Fourth Council of Constantinople]] of 869-870 and 879-880 is disputed by [[Catholicism]] and [[Eastern Orthodoxy]]. | ||

| − | The | + | === Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers === |

| + | The early Church Fathers have already been mentioned above; however, Late Antique Christianity produced a great many renowned Fathers who wrote volumes of theological texts, including [[Saint]]s [[Augustine of Hippo|Augustine]], [[Gregory of Nazianzus|Gregory Nazianzus]], [[Cyril of Jerusalem]], [[Ambrose|Ambrose of Milan]], [[Jerome]], and others. What resulted was a golden age of literary and scholarly activity unmatched since the days of [[Virgil]] and [[Horace]]. Some of these fathers, such as [[John Chrysostom]] and [[Athanasius of Alexandria|Athanasius]], suffered exile, persecution, or martyrdom from heretical [[Byzantine Emperors]]. Many of their writings are translated into English in the compilations of [[Nicene]] and [[Post-Nicene]] Fathers. | ||

| − | + | ===The Pentarchy=== | |

| + | By the fifth century, the [[ecclesiastical]] had evolved a [[hierarchical]] "[[pentarchy]]" or system of five sees ([[patriarchates]]), with a settled order of precedence, had been established. Rome, as the ancient center and largest city of the empire, was understandably given the presidency or primacy of honor within the pentarchy into which Christendom was now divided; though it was and still held that the patriarch of Rome was the first among equals. | ||

| − | + | The list below are the five Pentarchs of the original Pentarchy of the Roman Empire. | |

| + | * [[Pope|Rome]] (Sts. [[Saint Peter|Peter]] and [[Paul the Apostle|Paul]]), i.e., the Pope, the only Pentarch in the [[Western Roman Empire]]. | ||

| + | * [[Patriarch of Alexandria|Alexandria]] (St. [[Mark the Evangelist|Mark]]), currently in [[Egypt]] | ||

| + | * [[Patriarch of Antioch|Antioch]] (St. [[Saint Peter|Peter]]), currently in [[Turkey]] | ||

| + | * [[Patriarch of Jerusalem|Jerusalem]] (St. [[James the Just|James]]), currently in [[Israel]]/[[Palestine]] | ||

| + | * [[Patriarch of Constantinople|Constantinople]] (St. [[Saint Andrew|Andrew]]), currently in [[Turkey]] | ||

| − | + | === Monasticism === | |

| + | {{Main|Christian monasticism}} | ||

| − | + | [[Monasticism]] is a form of [[asceticism]] whereby one renounces worldly pursuits ''(in contempu mundi)'' and concentrates solely on heavenly and spiritual pursuits, especially by the virtues humility, poverty, and chastity. It began early in the Church as a family of similar traditions, modeled upon Scriptural examples and ideals, and with roots in certain strands of Judaism. St. [[John the Baptist]] is seen as the archetypical [[monk]], and monasticism was also inspired by the organization of the Apostolic community as recorded in ''Acts of the Apostles''. | |

| − | + | There are two forms of monasticism: [[hermit|eremetic]] and [[Cenobitic Monasticism|cenobitic]]. Eremetic monks, or hermits, live in solitude, whereas cenobitic monks live in communities, generally in a [[monastery]], under a rule (or code of practice) and are governed by an [[abbot]]. Originally, all Christian monks were hermits, following the example of [[Anthony the Great]]. However, the need for some form of organized spiritual guidance lead Saint [[Pachomius]] in 318 to organize his many followers in what was to become the first monastery. Soon, similar institutions were established throughout the [[Egypt]]ian [[desert]] as well as the rest of the eastern half of the Roman Empire. Central figures in the development of monasticism were, in the East, St. [[Basil of Caesarea|Basil the Great]], and [[Saint Benedict]] in the West, who created the famous [[Rule of Saint Benedict|Benedictine Rule]], which would become the most common rule throughout the [[Middle Ages]]. | |

| − | + | ==Growing tensions between East and West== | |

| − | + | The cracks and fissures in Christian unity which led to the [[East-West Schism|Great Schism]] started to become evident as early as the fourth century. Although 1054 is the date usually given for the beginning of the [[Great Schism]], there is, in fact, no specific date on which the schism occurred. What really happened was a complex chain of events whose climax culminated with the sacking of [[Constantinople]] by the [[Fourth Crusade]] in 1204. | |

| − | |||

| − | The | + | The events leading to schism were not exclusively theological in nature. [[Culture|Cultural]], [[Politics|political]], and [[Language|linguistic]] differences were often mixed with the [[Theology|theological]]. Any narrative of the schism which emphasizes one at the expense of the other will be fragmentary. Unlike the [[Copts]] or Armenians who broke from the Church in the fifth century, the eastern and western parts of the Church remained loyal to the faith and authority of the seven ecumenical councils. They were united, by virtue of their common faith and tradition, in one Church. |

| − | + | Nonetheless, the transfer of the Roman capital to [[Constantinople]] inevitably brought mistrust, rivalry, and even jealousy to the relations of the two great sees, [[Rome]] and Constantinople. It was easy for Rome to be jealous of Constantinople at a time when it was rapidly losing its political prominence. In fact, Rome refused to recognize the conciliar legislation which promoted Constantinople to second rank. But the estrangement was also helped along by the [[Germany|German]] invasions in the West, which effectively weakened contacts. The rise of [[Islam]] with its conquest of most of the Mediterranean coastline (not to mention the arrival of the pagan Slavs in the Balkans at the same time) further intensified this separation by driving a physical wedge between the two worlds. The once homogeneous unified world of the Mediterranean was fast vanishing. Communication between the Greek East and the Latin West by the 600s had become dangerous and practically ceased.<ref name=Schism>[http://www.orthodoxinfo.com/general/greatschism.aspx The Great Schism: The Estrangement of Eastern and Western Christendom]. ''Orthodoxinfo.com''. Retrieved November 25, 2019.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Two basic problems—the primacy of the bishop of Rome and the procession of the Holy Spirit—were involved. These doctrinal novelties were first openly discussed in [[Photius]]'s patriarchate. | |

| − | + | By the fifth century, Christendom was divided into a pentarchy of five sees with Rome holding the primacy. This was determined by canonical decision and did not entail [[hegemony]] of any one local church or patriarchate over the others. However, Rome began to interpret her primacy in terms of sovereignty, as a God-given right involving universal jurisdiction in the Church. The collegial and conciliar nature of the Church, in effect, was gradually abandoned in favor of supremacy of unlimited papal power over the entire Church. These ideas were finally given systematic expression in the West during the [[Gregorian Reform]] movement of the eleventh century. The Eastern churches viewed Rome's understanding of the nature of episcopal power as being in direct opposition to the Church's essentially conciliar structure and thus saw the two ecclesiologies as mutually antithetical. | |

| − | + | This fundamental difference in ecclesiology would cause all attempts to heal the schism and bridge the divisions to fail. Characteristically, Rome insisted on basing her [[Monarchy|monarchical]] claims to "true and proper jurisdiction" (as the Vatican Council of 1870 put it) on Saint Peter. This "Roman" exegesis of ''Matthew 16:18,'' however, was unknown to the patriarchs of Eastern Orthodoxy. For them, specifically, Saint Peter's primacy could never be the exclusive prerogative of any one bishop. All bishops must, like Saint Peter, confess Jesus as the Christ and, as such, all are Saint Peter's successors. The churches of the East gave the Roman See primacy but not supremacy. The Pope being the first among equals, but not [[PapalInfalliibility|infallible]] and not with absolute authority.<ref>Kallistos Ware, ''The Orthodox Church'' (London: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press, 1995, ISBN 978–0913836583).</ref> | |

| − | + | The other major irritant to Eastern Orthodoxy was the Western interpretation of the procession of the [[Holy Spirit]]. Like the primacy, this too developed gradually and entered the Creed in the West almost unnoticed. This theologically complex issue involved the addition by the West of the [[Filioque clause|Latin phrase filioque]] ("and from the Son") to the Creed. The original Creed sanctioned by the councils and still used today by the Orthodox Church did not contain this phrase; the text simply states "the Holy Spirit, the Lord and Giver of Life, who proceeds from the Father." Theologically, the [[Latin]] interpolation was unacceptable to Eastern Orthodoxy since it implied that the Spirit now had two sources of origin and procession, the Father and the Son, rather than the Father alone.<ref>Vladimir Lossky, ''The Mystical Theology of the Eastern Church'' ((1991) reprint ed. SVS Press, 1997, ISBN 0913836311).</ref> In short, the balance between the three persons of the [[Trinity]] was altered and the understanding of the Trinity and God confused. | |

| − | The | + | The result, the Orthodox Church believed, then and now, was theologically indefensible. But in addition to the [[dogma]]tic issue raised by the filioque, the Byzantines argued that the phrase had been added unilaterally and, therefore, illegitimately, since the East had never been consulted.<ref>Nikolai O. Lossky, ''History of Russian Philosophy'' (International Universities Press, 1951) Quoting [[Aleksey Khomyakov]], 87: The legal formalism and logical rationalism of the [[Roman Catholic Church]] have their roots in the Roman State. These features developed in it more strongly than ever when the Western Church without consent of the Eastern introduced into the Nicene Creed the filioque clause. Such arbitrary change of the creed is an expression of pride and lack of love for one's brethren in the faith. "In order not to be regarded as a schism by the Church, Romanism was forced to ascribe to the bishop of Rome absolute infallibility." In this way Catholicism broke away from the Church as a whole and became an organization based upon external authority. Its unity is similar to the unity of the state: it is not necessarily rational but is rationalistic and legally formal. Rationalism has led to the doctrine of the works of supererogation, established a balance of duties and merits between God and man, weighing in the scales sins and prayers, trespasses and deeds of expiation; it adopted the idea of transferring one person's debts or credits to another and legalized the exchange of assumed merits; in short, it introduced into the sanctuary of faith the mechanism of a banking house. </ref> In the final analysis, only another ecumenical council could introduce such an alteration. Indeed the councils, which drew up the original Creed, had expressly forbidden any subtraction or addition to the text. |

| − | + | == Church of the Early Middle Ages (476–800) == | |

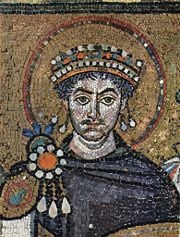

| + | [[Image:Meister von San Vitale in Ravenna 004.jpg|right|thumb|180px|[[Mosaic]] of [[Justinian I]] in the church of San Vitale, Ravenna, [[Italy]]]] | ||

| − | + | The Church in the [[Early Middle Ages]] covers the time from the deposition of the last Western Emperor in 476 and his replacement with a barbarian king, [[Odoacer]], to the coronation of [[Charlemagne]] as "Emperor of the Romans" by Pope [[Leo III]] in Rome on [[Christmas]] Day, 800. The year 476, however, is a rather artificial division.<ref> Gerberding and Moran Cruz, 33.</ref> In the East, Roman imperial rule continued through the period historians now call the [[Byzantine Empire]]. Even in the West, where imperial political control gradually declined, distinctly Roman culture continued long afterwards; thus historians today prefer to speak of a "transformation of the Roman world" rather than a "fall of the Roman Empire." The advent of the Early Middle Ages was a gradual and often localized process whereby, in the West, rural areas became power centers whilst urban areas declined. With the [[Muslim]] invasions of the seventh century, the Western (Latin) and Eastern (Greek) areas of Christianity began to take on distinctive shapes. Whereas in the East the Church maintained its structure and character and evolved more slowly, in the West the [[Bishops of Rome]] (i.e., the Popes) were forced to adapt more quickly and flexibly to drastically changing circumstances. In particular whereas the bishops of the East maintained clear allegiance to the Eastern Roman Emperor, the Bishop of Rome, while maintaining nominal allegiance to the Eastern Emperor, was forced to negotiate delicate balances with the "barbarian rulers" of the former Western provinces. Although the greater number of Christians remained in the East, the developments in the West would set the stage for major developments in the Christian world during the later [[Middle Ages]]. | |

| − | + | === Conversion of barbarian hinterland === | |

| + | [[Image:Ivanov pagans.jpg|thumb|275px|''Christians and Pagans,'' a painting by [[Sergei Ivanov (painter)|Sergei Ivanov]]]] | ||

| + | As the political boundaries of the Western Roman Empire diminished and then collapsed, Christianity spread beyond the old borders of the Empire and into lands that had never been Romanized. | ||

| − | + | ==== Ireland and Irish missionaries ==== | |

| + | Beginning in the fifth century, a unique culture developed around the [[Irish Sea]] consisting of what today would be called [[Wales]] and [[Ireland]]. In this environment, Christianity spread from [[Roman Britain]] to Ireland, especially aided by the missionary activity of [[Saint Patrick|St. Patrick]]. Patrick had been captured into [[slavery]] in Ireland and, following his escape and later consecration as bishop, he returned to the isle that had enslaved him so that he could bring them the [[Gospel]]. Soon, Irish [[Missionary|missionaries]] such as Saints [[Columba]] and [[Columbanus]] spread this Christianity, with its distinctively Irish features, to [[Scotland]] and the Continent. One such feature was the system of private [[penitence]], which replaced the former practice of penance as a public rite.<ref>On the development of penitential practice, see John T. McNeill and Helena M. Gamer, (translators), ''Medieval Handbooks of Penance'' (1938) reprint ed. (Columbia University Press, 1990, ISBN 0231096291), 9–54.</ref> | ||

| − | + | ==== Anglo-Saxons (English) ==== | |

| + | Although Britain had been a [[Roman Britain|Roman province]], in 407 the imperial legions left the isle, and the Roman elite followed. Some time later that century, various barbarian tribes went from raiding and pillaging the island to settling and invading. These tribes are referred to as the "[[Anglo-Saxons]]," predecessors of the English. They were entirely pagan, having never been part of the Empire, and although they experienced Christian influence from the surrounding peoples, they were [[Religious conversion|converted]] by the mission of [[Augustine of Canterbury|Saint Augustine]] sent by [[Pope Gregory I|Pope Gregory the Great]]. Later, under [[Theodore of Tarsus|Archbishop Theodore]], the Anglo-Saxons enjoyed a golden age of culture and scholarship. Soon, important English missionaries such as Saints [[Wilfrid]], [[Willibrord]], [[Lullus]] and [[Boniface]] would begin evangelizing their Saxon relatives in Germany. | ||

| − | + | ==== Franks ==== | |

| + | {{seealso|Franks|Merovingian}} | ||

| + | [[Image:Chlodwigs taufe.jpg|thumb|225px|left|[[Saint Remigius]] baptizes [[Clovis I]].]] | ||

| − | The | + | The largely Christian Gallo-Roman inhabitants of [[Gaul]] (modern [[France]]) were overrun by Germanic [[Franks]] in the early fifth century. The native inhabitants were persecuted until the Frankish King, [[Clovis I]] converted from [[paganism]] to [[Roman Catholic]]ism in 496. Clovis insisted that his fellow nobles follow suit, strengthening his newly-established kingdom by uniting the faith of the rulers with that of the ruled. |

| − | + | ==== Netherlands and non-Frankish Germany ==== | |

| + | In 698 the [[Northumbria]]n [[Benedictine]] [[monk]], Saint [[Willibrord]] was commissioned by [[Pope Sergius I]] as bishop of the [[Frisian]]s in what is now the [[Netherlands]]. Willibrord established a church in [[Utrecht]]. | ||

| − | + | Much of Willibrord's work was wiped out when the pagan [[Radbod, king of the Frisians]] destroyed many Christian centers between 716 and 719. In 717, the English missionary [[Boniface]] was sent to aid Willibrord, re-establishing churches in Frisia and continuing to preach throughout the pagan lands of [[Germany]]. Boniface was killed by pagans in 754. | |

| − | + | ==== Scandinavia ==== | |

| + | Early evangelization in [[Scandinavia]] was begun by [[Ansgar]], [[Archbishopric of Bremen|Archbishop of Bremen]], "Apostle of the North." Ansgar, a native of [[Amiens]], was sent with a group of monks to Jutland, [[Denmark]] around 820 at the time of the pro-Christian Jutish king [[Harald Klak]]. The mission was only partially successful, and Ansgar returned two years later to Germany, after Harald had been driven out of his kingdom. In 829 Ansgar went to Birka on [[Lake Mälaren]], [[Sweden]], with his aide [[friar]] Witmar, and a small congregation was formed in 831 which included the king's own steward Hergeir. Conversion was slow, however, and most Scandinavian lands were only completely Christianized at the time of rulers such as [[Saint Canute IV]] of Denmark and [[Olaf I of Norway]] in the years following 1000 C.E. | ||

| − | + | ===Early Medieval Papacy=== | |

| + | The city of [[Rome]] was embroiled in the turmoil and devastation of Italian peninsular warfare during the [[Early Middle Ages]]. Emperor [[Justinian I]] attempted to reassert imperial dominion in [[Italy]] against the Gothic aristocracy. The subsequent campaigns were more or less successful, and the Imperial [[Exarch]]ate was established in Ravenna to oversee Italy, though actually imperial influence was often limited. However, the weakened peninsula then experienced the invasion of the [[Lombards]], and the resulting warfare essentially left Rome to fend for itself. Thus the popes, out of necessity, found themselves feeding the city with grain from papal estates, negotiating treaties, paying protection money to Lombard warlords, and, failing that, hiring soldiers to defend the city.<ref>Richards, 36.</ref>Eventually, the failure of the Empire to send aid resulted in the popes turning for support from other sources, especially the [[Franks]]. | ||

| − | + | === Carolingian Renaissance === | |

| + | {{main|Carolingian Renaissance}} | ||

| + | The [[Carolingian]] Renaissance was a period of intellectual and cultural revival during the late eighth and ninth centuries, mostly during the reigns of [[Charlemagne]] and [[Louis the Pious]]. There was an increase of [[literature]], the [[art]]s, [[architecture]], [[jurisprudence]], [[Liturgy|liturgical]] and [[Scripture|scriptural]] studies. The period also saw the development of [[Carolingian minuscule]], the ancestor of modern lower-case script, and the standardization of [[Latin]] which had hitherto become varied and irregular. To address the problems of illiteracy among clergy and court scribes, Charlemagne founded schools and attracted the most learned men from all of Europe to his court, such as [[Theodulf]], [[Paul the Deacon]], [[Angilbert]], [[Paulinus of Aquileia]], and [[Alcuin of York]]. | ||

| − | The | + | == Church of the High Middle Ages (800–1499) == |

| + | The High Middle Ages is the period from the coronation of [[Charlemagne]] in 800 to the close of the fifteenth century, which saw the fall of [[Constantinople]] (1453), the end of the [[Hundred Years War]] (1453), the discovery of the New World (1492), and thereafter the [[Protestant Reformation]] (1515). | ||

| − | + | ===Conversion of East and South Slavs=== | |

| + | [[Image:Cyril Metodej.jpg|thumb|250px|left|Saint Cyril and Saint Methodius Monument on [[Radhošť|Mount Radhošť]]]] | ||

| − | + | Though by 800 Western Europe was ruled entirely by Christian kings, [[Eastern Europe]] remained an area of [[missionary]] activity. For example, in the ninth century Saints [[Saint Cyril|Cyril]] and [[Saint Methodius|Methodius]] had extensive missionary success in Eastern Europe among the [[Slavic peoples]], translating the Bible and liturgy into [[Old Church Slavonic|Slavonic]]. The [[Baptism of Kiev]] in 988 spread Christianity throughout [[Kievan Rus']], establishing Christianity among the [[Ukraine]], [[Belarus]] and [[Russia]]. | |

| − | + | In the ninth and tenth centuries, Christianity made great inroads into Eastern Europe, including Kievan Rus'. The evangelization, or Christianization, of the Slavs was initiated by one of [[Byzantium]]'s most learned churchmen—the Patriarch [[Photius]]. The Byzantine emperor [[Michael III]] chose Cyril and Methodius in response to a request from [[Rastislav]], the king of [[Moravia]] who wanted missionaries that could minister to the Moravians in their own language. The two brothers spoke the local [[Slavonic languages|Slavonic]] vernacular and translated the [[Bible]] and many of the prayer books. As the translations prepared by them were copied by speakers of other dialects, the hybrid literary language [[Old Church Slavonic]] was created. | |

| − | + | Bulgaria was officially recognized as a [[patriarchate]] by Constantinople in 945, Serbia in 1346, and Russia in 1589. All these nations, however, had been converted long before these dates. | |

| − | + | The missionaries to the East and South Slavs had great success in part because they used the people's native language rather than [[Latin]] as the Roman priests did, or [[Greek language|Greek]]. | |

| − | + | ====Conversion of the Serbs and Bulgarians==== | |

| − | + | Methodius later went on to convert the [[Serbia|Serbs]]. Some of the disciples, namely [[Saint Kliment]], [[Saint Naum]] who were of noble [[Bulgarians|Bulgarian]] descent and [[Saint Angelaruis]], returned to [[Bulgaria]] where they were welcomed by the Bulgarian [[Tsar]] [[Boris I of Bulgaria|Boris I]] who viewed the Slavonic liturgy as a way to counteract Greek influence in the country. In a short time the disciples of Cyril and Methodius managed to prepare and instruct the future Slav Bulgarian clergy into the [[Glagolitic alphabet]] and the biblical texts and in AD 893, Bulgaria expelled its Greek clergy and proclaimed the [[Bulgarian language|Slavonic language]] as the official language of the church and the state. | |

| − | + | ====Conversion of the Rus'==== | |

| + | [[Image:Vasnetsov Bapt Vladimir.jpg|200px|thumb|Baptism of Vladimir]] | ||

| + | The success of the conversion of the Bulgarians facilitated the conversion of other East [[Slavic peoples]], most notably the [[Rus' (people)|Rus']], predecessors of [[Belarusians]], [[Russians]], and [[Ukrainians]], as well as [[Rusyns]]. By the beginning of the eleventh century most of the pagan Slavic world, including Russia, Bulgaria and Serbia, had been converted to Byzantine Christianity. | ||

| − | + | The traditional event associated with the conversion of Russia is the [[baptism]] of [[Vladimir of Kiev]] in 989, on which occasion he was also married to the Byzantine princess Anna, the sister of the Byzantine Emperor [[Basil II]]. However, Christianity is documented to have predated this event in the city of [[Kiev]] and in Georgia. | |

| − | + | Today the [[Russian Orthodox Church]] is the largest of the Orthodox Churches. | |

| − | + | ===Iconoclasm=== | |

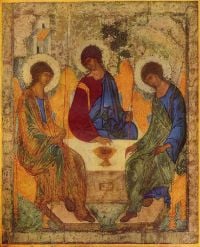

| + | [[Image:Andrej Rublëv 001.jpg|left|200px|thumb|[[Andrei Rublev]]'s [[Trinity]] ]] | ||

| + | {{main|Iconoclasm (Byzantine)}} | ||

| + | [[Icon#The Iconoclast period|Iconoclasm]] as a movement began within the Eastern Christian Byzantine church in the early 8th Century, following a series of heavy military reverses against the [[Islam|Muslims]]. Sometime between 726-730 the Byzantine Emperor [[Leo III the Isaurian]] ordered the removal of an image of Jesus prominently placed over the Chalke gate, the ceremonial entrance to the [[Great Palace of Constantinople]], and its replacement with a [[cross]]. This was followed by orders banning the pictorial representation of the family of Christ, subsequent Christian saints, and biblical scenes. In the West, [[Pope Gregory III]] held two [[synod]]s at Rome and condemned Leo's actions. In Leo's realms, the [[Iconoclast Council]] at Hieria, 754 ruled that the culture of holy portraits was not of a Christian origin and therefore heretical<ref>Epitome, Iconoclast Council at Hieria, 754 </ref>. The movement destroyed much of the Christian church's early artistic history, to the great loss of subsequent art and religious historians. The iconoclastic movement itself was later defined as heretical in 787 under the [[Ecumenical Council#List of ecumenical councils|Seventh Ecumenical Council]], but enjoyed a brief resurgence between 815 and 842. | ||

| − | The | + | ===Monastic Reform Movement=== |

| + | [[Image:Clocher abbaye cluny 2.JPG|right|200px|thumb|A view of the [[Abbey of Cluny]].]] | ||

| + | From the 6th century onward most of the monasteries in the West were of the [[Benedictine]] Order. Owing to the stricter adherence to a reformed [[Benedictine#Rule of St. Benedict|Benedictine rule]], the [[abbey]] of [[Cluny Abbey|Cluny]] became the acknowledged leader of western [[monasticism]] from the later 10th century. A sequence of highly competent [[abbots of Cluny]] were statesmen on an international level. The monastery of Cluny itself became the grandest, most prestigious and best endowed monastic institution in [[Europe]]. Cluny created a large, federated order in which the administrators of subsidiary houses served as deputies of the abbot of Cluny and answered to him. Free of lay and episcopal interference, responsible only to the papacy, the Cluniac spirit was a revitalizing influence on the Norman church. The height of Cluniac influence was from the second half of the tenth century through the early twelfth. | ||

| − | The | + | The next wave of monastic reform came with the [[Cistercians|Cistercian Movement]]. The first Cistercian abbey was founded by [[Robert of Molesme]] in 1098, at [[Cîteaux|Cîteaux Abbey]]. The keynote of Cistercian life was a return to a literal observance of the rule of Saint Benedict. Rejecting the developments that the Benedictines had undergone, they tried to reproduce the life exactly as it had been in [[Benedict of Nursia|Saint Benedict]]'s time, indeed in various points they went beyond it in austerity. The most striking feature in the reform was the return to manual labor, and especially to field-work, which became a special characteristic of Cistercian life. |

| + | [[Image:Bernhard von Clairvaux (Initiale-B).jpg|left|thumb|Saint [[Bernard of Clairvaux]], in a medieval [[illuminated manuscript]].]] | ||

| + | Inspired by Saint [[Bernard of Clairvaux]], the Cistercians became the main force of technological diffusion in medieval Europe. By the end of the twelfth century the Cistercian houses numbered 500; in the thirteenth a hundred more were added; and at its height in the fifteenth century, the order claimed to have close to 750 houses. Most of these were built in wilderness areas, and played a major part in bringing such isolated parts of Europe into economic cultivation. | ||

| − | + | === Mendicant orders === | |

| + | A third level of monastic reform was provided by the establishment of the [[Mendicant]] orders. Commonly known as ''[[Friar]]s,'' mendicants are members of religious communities that live under a monastic rule but, rather than residing in the seclusion of a [[monastery]], they emphasize public [[evangelism]] and are thus known for preaching, [[missionary]] activity, and [[education]], as well as the traditional vows of [[poverty]], [[chastity]] and [[obedience]]. Beginning in the twelfth century, the Franciscan order was instituted by the followers of [[Francis of Assisi]], and thereafter the [[Dominican Order]] was begun by [[Saint Dominic]]. | ||

| − | + | === Investiture Controversy === | |

| − | + | {{main|Investiture Controversy}} | |

| − | + | [[Image:Canossa-gate.jpg|right|thumb|250px|Henry IV at the gate of Canossa, by August von Heyden]] | |

| − | + | The [[Investiture]] Controversy, or Lay investiture controversy, was the most significant conflict between secular and religious powers in [[medieval Europe]]. It began as a dispute in the 11th century between the [[Holy Roman Emperor]] [[Henry IV, Holy Roman Emperor|Henry IV]], and Pope [[Gregory VII]] concerning who would appoint bishops (investiture). The end of [[lay investiture]] threatened to undercut imperial power, for the benefit of Church reform, as the pope intended, and for ambitious noblemen as well. | |

| − | + | [[Bishop]]s collected revenues from estates attached to their [[bishopric]]. Noblemen who held lands ([[fiefdom]]s) passed those lands on within their family. However, because bishops had no legitimate children, when a bishop died it was the king's right to appoint a successor. So, while a king had little recourse in preventing noblemen from acquiring powerful domains via [[inheritance]] and dynastic marriages, a king could keep careful control of lands under the domain of his bishops. Kings would bestow bishoprics to members of noble families whose friendship he wished to secure. Furthermore, if a king left a bishopric vacant, then he collected the estates' revenues until a bishop was appointed, when in theory he was to repay the earnings. The infrequence of this repayment was an obvious source of dispute. The Church wanted to end this lay investiture because of the potential corruption, not only from vacant sees but also from other practices such as [[simony]]. Thus, the Investiture Contest was part of the Church's attempt to reform the episcopate and provide better [[pastoral care]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Pope Gregory VII issued the ''[[Dictatus Papae]]'', which declared that the pope alone could appoint or depose bishops, or translate them to other sees. [[Henry VI]]'s rejection of the decree led to his [[excommunication]] and a ducal revolt; eventually Henry received absolution after dramatic public penance barefoot in Alpine snow and cloaked in a hairshirt, though the revolt and conflict of investiture continued. Likewise, a similar controversy occurred in England between [[Henry I of England|King Henry I]] and [[Anselm of Canterbury|St. Anselm]], [[Archbishop of Canterbury]], over investiture and ecclesiastical revenues collected by the king during an episcopal vacancy. The English dispute was resolved by the [[Concordat of London]], 1107, where the king renounced his claim to invest bishops but continued to require an oath of fealty from them upon their election. This was a partial model for the [[Concordat of Worms]] ''(Pactum Calixtinum)'', which resolved the Imperial investiture controversy with a compromise that allowed secular authorities some measure of control but granted the selection of bishops to their [[canon (priest)|cathedral canons]]. As a symbol of the compromise, lay authorities invested bishops with their secular authority symbolized by the lance, and ecclesiastical authorities invested bishops with their spiritual authority symbolized by the [[Ecclesiastical ring|ring]] and the [[Crozier|staff]]. | |

| − | + | === Sanctification of knighthood === | |

| + | [[File:ONL (1887) 1.150 - A Knight Templar.jpg|thumb|180px|[[Knights Templar]], organized to defend the Christian Holy Land]] | ||

| − | The | + | The nobility of the [[Middle Ages]] was a military class; in the Early Medieval period a king ''(rex)'' attracted a band of loyal warriors ''(comes)'' and provided for them from his conquests. As the Middle Ages progressed, this system developed into a complex set of [[Feudalism|feudal]] ties and obligations. As Christianity had been accepted by barbarian nobility, the Church sought to prevent ecclesiastical land and clergymen, both of which came from the nobility, from embroilment in martial conflicts. By the early eleventh century, clergymen and peasants were granted immunity from violence—the ''Peace of God'' ''(Pax Dei)''. Soon the warrior elite itself became "sanctified," for example fighting was banned on holy days—the ''Truce of God'' ''(Treuga Dei)''. The concept of [[chivalry]] developed, emphasizing honor and loyalty amongst [[knight]]s, and, with the advent of Crusades, holy orders of knights were established who perceived themselves as called by God to defend Christendom against [[Muslim]] advances in Spain, Italy, and the [[Holy Land]], and pagan strongholds in Eastern Europe. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ===Crusades=== | |

| + | The [[Crusades]] were a series of military conflicts conducted by Christian [[knight]]s for the defense of Christians and for the expansion of Christian domains. Generally, the crusades refer to the campaigns in the [[Holy Land]] against [[Muslim]] forces sponsored by the Papacy. There were other crusades against Islamic forces in southern [[Spain]], southern [[Italy]], and [[Sicily]], as well as the campaigns of [[Teutonic Knights]] against pagan strongholds in Eastern Europe. A few crusades such as the [[Fourth Crusade]] were waged within Christendom against groups that were considered heretical and schismatic (also see the [[Battle of the Ice]] and the [[Northern Crusades]]). | ||

| − | + | [[Image:Krak des chavaliers plaine.jpg|thumb|250px|View over the walls of [[Crac des Chevaliers|Krak des Chavaliers]], near impenetrable crusaders' fortress.]] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The [[Holy Land]] had been part of the Roman Empire, and thus [[Byzantine Empire]], until the Islamic conquests of the seventh and eighth centuries. Thereafter, Christians had generally been permitted to visit the sacred places in the Holy Land until 1071, when the [[Seljuk Turks]] closed Christian [[pilgrimage]]s and assailed the Byzantines, defeating them at the [[Battle of Manzikert]]. Emperor [[Alexius I]] asked for aid from [[Pope Urban II]] (1088–1099) for help against Islamic aggression. He probably expected money from the pope for the hiring of mercenaries. Instead, Urban II called upon the knights of Christendom in a speech made at the [[Council of Clermont]] in November 1095, combining the idea of pilgrimage to the Holy Land with that of waging a [[holy war]] against [[infidel]]s. | |