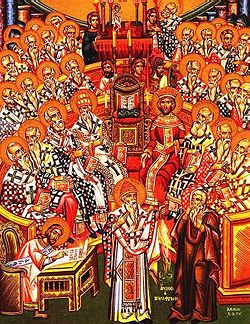

First Council of Nicaea

The First Council of Nicaea was the earliest ecumenical council (meaning "worldwide council" - though actually limited to the Roman Empire) of the Christian Church, held in the city of Nicaea in 325 C.E. The council summoned all the Bishops of the Christian Church who produced a significant statement of Christian doctrine, known as the Nicene Creed that sought to clarify issues of Christology, in particular, whether Jesus was of the same substance as God the Father or merely of similar substance. Saint Alexander of Alexandria and Athanasius took the first position while the popular presbyter Arius took the second. The council voted against Arius[1]

The council was called by the Roman Emperor Constantine I in order to resolve christological disagreements and to consolidate greater unity in his empire. The event was historically significant because it was the first effort to attain consensus in the church through an assembly representing all of Christendom.[2] Further, "Constantine in convoking and presiding over the council signaled a measure of imperial control over the church."[2] The Nicene Creed established a precedent for subsequent ecumenical councils of bishops' to create statements of belief and canons of doctrinal orthodoxy— the intent being to define unity of beliefs for the whole of Christendom.

Character and purpose

The First Council of Nicaea was convened by Constantine I upon the recommendations of a synod led by Hosius of Cordoba in the Eastertide of 325 C.E. This synod had been charged with investigation of the trouble brought about by the Arian controversy in the Greek-speaking east.[3] To most bishops, the teachings of Arius were heretical and dangerous to the salvation of souls. In the summer of 325 C.E., the bishops of all provinces were summoned to Nicaea (now known as İznik, in modern-day Turkey), a place easily accessible to the majority of them, particularly those of Asia Minor, Syria, Palestine, Egypt, Greece, and Thrace.

Approximately 250 to 318 bishops attended, from every region of the Empire except Britain. This was the first general council in the history of the Church since the Apostolic Council of Jerusalem, which had established the conditions upon which Gentiles could join the Church.[4] The resolutions in the council, being ecumenical, were intended for the whole Church.

Attendees

Emperor Constantine had invited all 1800 bishops of the Christian church (about 1000 in the east and 800 in the west), but a lesser and unknown number attended. Eusebius of Caesarea counted 250,[5] Athanasius of Alexandria counted 318,[6] and Eustathius of Antioch counted 270[7] (all three were present at the council). Later, Socrates Scholasticus recorded more than 300,[8] and Evagrius,[9] Hilarius,[10] Saint Jerome[11] and Rufinus recorded 318.

The participating bishops were given free travel to and from their episcopal sees to the council, as well as lodging. These bishops did not travel alone; each one had permission to bring with him two priests and three deacons; so the total number of attendees would have been above 1500. Eusebius speaks of an almost innumerable host of accompanying priests, deacons and acolytes.

A special prominence was also attached to this council because the persecution of Christians had just ended with the February 313 Edict of Milan by Emperors Constantine and Licinius.

The Eastern bishops formed the great majority. Of these, the first rank was held by the three patriarchs: Alexander of Alexandria,[12] Eustathius of Antioch,[12] and Macarius of Jerusalem.[12] Many of the assembled fathers—for instance, Paphnutius of Thebes, Potamon of Heraclea and Paul of Neocaesarea[12]—had stood forth as confessors of the faith and came to the council with the marks of persecution on their faces. Other remarkable attendees were Eusebius of Nicomedia; Eusebius of Caesarea; Nicholas of Myra; Aristakes of Armenia (son of Saint Gregory the Illuminator); Leontius of Caesarea; Jacob of Nisibis, a former hermit; Hypatius of Granga; Protogenes of Sardica; Melitius of Sebastopolis; Achilleus of Larissa; Athanasius of Thessaly[12] and Spyridion of Trimythous, who even while a bishop made his living as a shepherd. From foreign places came a Persian bishop John, a Gothic bishop Theophilus and Stratophilus, bishop of Pitiunt in Egrisi (located at the border of modern-day Russia and Georgia outside of the Roman Empire).

The Latin-speaking provinces sent at least five representatives: Marcus of Calabria from Italia, Cecilian of Carthage from North Africa, Hosius of Córdoba from Hispania, Nicasius of Dijon from Gaul,[12] and Domnus of Stridon from the province of the Danube. Pope Silvester I declined to attend, pleading infirmity, but he was represented by two priests.

Athanasius of Alexandria, a young deacon and companion of Bishop Alexander of Alexandria, was among these assistants. Athanasius eventually spent most of his life battling against Arianism. Alexander of Constantinople, then a presbyter, was also present as representative of his aged bishop.[12]

The supporters of Arius included Secundus of Ptolemais,[13] Theonus of Marmarica,[14] Zphyrius, and Dathes, all of whom hailed from Libya and the Pentapolis. Other supporters included Eusebius of Nicomedia,[15] Eusebius of Caesarea, Paulinus of Tyrus, Actius of Lydda, Menophantus of Ephesus, and Theognus of Nicaea.[16][12]

"Resplendent in purple and gold, Constantine made a ceremonial entrance at the opening of the council, probably in early June, but respectfully seated the bishops ahead of himself."[4] He was present as an observer, but he did not vote. Constantine organized the Council along the lines of the Roman Senate. "Ossius [Hosius] presided over its deliberations; he probably, and the two priests of Rome certainly, came as representatives of the Pope."[4]

Agenda and procedure

The following issues were discussed at the council:

- The Arian question;

- The celebration of Passover;

- The Meletian schism;

- The Father and Son one in purpose or in person;

- The baptism of heretics;

- The status of the lapsed in the persecution under Licinius.

The council was formally opened May 20, 325 C.E. in the central structure of the imperial palace, with preliminary discussions on the Arian question. In these discussions, some dominant figures were Arius, with several adherents. “Some 22 of the bishops at the council, led by Eusebius of Nicomedia, came as supporters of Arius. But when some of the more shocking passages from his writings were read, they were almost universally seen as blasphemous.”[4] Bishops Theognis of Nicea and Maris of Chalcedon were among the initial supporters of Arius.

Eusebius of Caesarea called to mind the baptismal creed (symbol) of his own diocese at Caesarea in Palestine, as a form of reconciliation. The majority of the bishops agreed. For some time, scholars thought that the original Nicene Creed was based on this statement of Eusebius. Today, most scholars think that this Creed is derived from the baptismal creed of Jerusalem, as Hans Lietzmann proposed.[17] Another possibility is the Apostle's Creed.

In any case, as the council went on, the orthodox bishops won approval of every one of their proposals. After being in session for an entire month, the council promulgated on June 19 the original Nicene Creed. This profession of faith was adopted by all the bishops “but two from Libya who had been closely associated with Arius from the beginning.”[18] No historical record of their dissent actually exists; the signatures of these bishops are simply absent from the creed.

Arian controversy

The Arian controversy was a Christological dispute that began in Alexandria between the followers of Arius (the Arians) and the followers of St. Alexander of Alexandria (now known as Homoousians). Alexander and his followers believed that the Son was of the same substance as the Father, co-eternal with him. The Arians believed that they were different and that the Son, though he may be the most perfect of creations, was only a creation. A third group (now known as Homoiousians) tried to make a compromise position, saying that the Father and the Son were of similar substance.

Much of the debate hinged on the difference between being "born" or "created" and being "begotten." Arians saw these as the same; followers of Alexander did not. Indeed, the exact meaning of many of the words used in the debates at Nicaea were still unclear to speakers of other languages. Greek words like "essence" (ousia), "substance" (hypostasis), "nature" (physis), "person" (prosopon) bore a variety of meanings drawn from pre-Christian philosophers, which could not but entail misunderstandings until they were cleared up. The word homoousia, in particular, was initially disliked by many bishops because of its associations with Gnostic heretics (who used it in their theology), and because it had been condemned at the 264-268 C.E. Synods of Antioch.

"Homoousians" believed that to follow the Arian view destroyed the unity of the Godhead, and made the Son unequal to the Father, in contravention of the Scriptures ("The Father and I are one," John 10:30). Arians, on the other hand, believed that since God the Father created the Son, he must have emanated from the Father, and thus be lesser than the Father, in that the Father is eternal, but the Son was created afterward and, thus, is not eternal. The Arians likewise appealed to Scripture, quoting verses such as John 14:28: "the Father is greater than I." Homoousians countered the Arians' argument, saying that the Father's fatherhood, like all of his attributes, is eternal. Thus, the Father was always a father, and that the Son, therefore, always existed with him.

The Council declared that the Father and the Son are of the same substance and are co-eternal, basing the declaration in the claim that this was a formulation of traditional Christian belief handed down from the Apostles. This belief was expressed in the Nicene Creed.

The Nicene Creed

The Creed was originally written in Greek, owing to the location of the city of Nicaea, and the predominant language spoken when it was written. Eventually it was translated into Latin[19] and today there are many English translations of the creed including the following:

- We believe in one God, the Father Almighty, the maker of heaven and earth, of things visible and invisible.

- And in one Lord Jesus Christ, the Son of God, the begotten of God the Father, the Only-begotten, that is of the essence of the Father.

- God of God, Light of Light, true God of true God, begotten and not made; of the very same nature of the Father, by Whom all things came into being, in heaven and on earth, visible and invisible.

- Who for us humanity and for our salvation came down from heaven, was incarnate, was made human, was born perfectly of the holy virgin Mary by the Holy Spirit.

- By whom He took body, soul, and mind, and everything that is in man, truly and not in semblance.

- He suffered, was crucified, was buried, rose again on the third day, ascended into heaven with the same body, [and] sat at the right hand of the Father.

- He is to come with the same body and with the glory of the Father, to judge the living and the dead; of His kingdom there is no end.

- We believe in the Holy Spirit, in the uncreated and the perfect; Who spoke through the Law, prophets, and Gospels; Who came down upon the Jordan, preached through the apostles, and lived in the saints.

- We believe also in only One, Universal, Apostolic, and [Holy] Church; in one baptism in repentance, for the remission, and forgiveness of sins; and in the resurrection of the dead, in the everlasting judgement of souls and bodies, and the Kingdom of Heaven and in the everlasting life.[20]

Some of the key points of the creed were as follows:

- Jesus Christ is described as "God from God, Light from Light, true God from true God," confirming his divinity. When all light sources were natural, the essence of light was considered to be identical, regardless of its form.

- Jesus Christ is said to be "begotten, not made," asserting his co-eternalness with God, and confirming it by stating his role in the Creation.

- Finally, he is said to be "from the substance of the Father," in direct opposition to Arianism. Some ascribe the term Consubstantial, i.e., "of the same substance" (of the Father), to Constantine who, on this particular point, may have chosen to exercise his authority.

Of the third article only the words "and in the Holy Spirit" were left; the original Nicene Creed ended with these words. Then followed immediately the canons of the council. Thus, instead of a baptismal creed acceptable to both the homoousian and Arian parties, as proposed by Eusebius, the council promulgated one which was unambiguous in the aspects touching upon the points of contention between these two positions, and one which was incompatible with the beliefs of Arians. From earliest times, various creeds served as a means of identification for Christians, as a means of inclusion and recognition, especially at baptism. In Rome, for example, the Apostles' Creed was popular, especially for use in Lent and the Easter season. In the Council of Nicaea, one specific creed was used to define the Church's faith clearly, to include those who professed it, and to exclude those who did not.

The text of this profession of faith is preserved in a letter of Eusebius to his congregation, in Athanasius, and elsewhere.

Bishop Hosius of Cordova, one of the firm Homoousians, may well have helped bring the council to consensus. At the time of the council, he was the confidant of the emperor in all Church matters. Hosius stands at the head of the lists of bishops, and Athanasius ascribes to him the actual formulation of the creed. Great leaders such as Eustathius of Antioch, Alexander of Alexandria, Athanasius, and Marcellus of Ancyra all adhered to the Homoousian position.

In spite of his sympathy for Arius, Eusebius of Caesarea adhered to the decisions of the council, accepting the entire creed. The initial number of bishops supporting Arius was small. After a month of discussion, on June 19, there were only two left: Theonas of Marmarica in Libya, and Secundus of Ptolemais. Maris of Chalcedon, who initially supported Arianism, agreed to the whole creed. Similarly, Eusebius of Nicomedia and Theognis of Nice also agreed.

The emperor carried out his earlier statement: everybody who refuses to endorse the Creed will be exiled. Arius, Theonas, and Secundus refused to adhere to the creed, and were thus exiled, in addition to being excommunicated. The works of Arius were ordered to be confiscated and consigned to the flames,[21] although there is no evidence that this occurred. Nevertheless, the controversy, already festering, continued in various parts of the empire.

Separation of Easter from Jewish Passover

After the June 19 settlement of the most important topic, the question of the date of the Christian Passover (Easter) was brought up. This feast is linked to the Jewish Passover, as the crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus occurred during that festival. By the year 300 C.E., some Churches had adopted a divergent style of celebrating the feast, placing the emphasis on the resurrection which they believed occurred on Sunday. Others however celebrated the feast on the 14th of the Jewish month Nisan, the date of the crucifixion according to the Bible's Hebrew calendar (Leviticus 23:5, John 19:14). Hence this group was called Quartodecimans, which is derived from the Latin for 14. The Eastern Churches of Syria, Cilicia, and Mesopotamia determined the date of Christian Passover in relation to the 14th day of Nisan, in the Bible's Hebrew calendar. Alexandria and Rome, however, followed a different calculation, attributed to Pope Soter, so that Christian Passover would never coincide with the Jewish observance and decided in favor of celebrating on the first Sunday after the first full moon following the vernal equinox, independently of the Bible's Hebrew calendar.

According to Louis Duchesne,[22] who founds his conclusions:

- on the conciliar letter to the Alexandrians preserved in Theodoret;[23]

- on the circular letter of Constantine to the bishops after the council;[24]

- on Athanasius;[25]

Epiphanius of Salamis wrote in the mid-fourth century "… the emperor … convened a council of 318 bishops … in the city of Nicea. … They passed certain ecclesiastical canons at the council besides, and at the same time decreed in regard to the Passover that there must be one unanimous concord on the celebration of God's holy and supremely excellent day. For it was variously observed by people…"[26]

The council assumed the task of regulating these differences, in part because some dioceses were determined not to have Christian Passover correspond with the Jewish calendar. "The feast of the resurrection was thenceforth required to be celebrated everywhere on a Sunday, and never on the day of the Jewish passover, but always after the fourteenth of Nisan, on the Sunday after the first vernal full moon. The leading motive for this regulation was opposition to Judaism…."[27]

The Council of Nicaea, however, did not declare the Alexandrian or Roman calculations as normative. Instead, the council gave the Bishop of Alexandria the privilege of announcing annually the date of Christian Passover to the Roman curia. Although the synod undertook the regulation of the dating of Christian Passover, it contented itself with communicating its decision to the different dioceses, instead of establishing a canon. There was subsequent conflict over this very matter.

Meletian Schism

The suppression of the Meletian schism was one of the three important matters that came before the Council of Nicaea. Meletius (bishop of Lycopolis in Egypt), it was decided, should remain in his own city of Lycopolis, but without exercising authority or the power to ordain new clergy; moreover he was forbidden to go into the environs of the town or to enter another diocese for the purpose of ordaining its subjects. Melitius retained his episcopal title, but the ecclesiastics ordained by him were to receive again the imposition of hands, the ordinations performed by Meletius being therefore regarded as invalid. Clergy ordained by Meletius were ordered to yield precedence to those ordained by Alexander, and they were not to do anything without the consent of Bishop Alexander.[28]

In the event of the death of a non-Meletian bishop or ecclesiastic, the vacant see might be given to a Meletian, provided he were worthy and the popular election were ratified by Alexander. As to Meletius himself, episcopal rights and prerogatives were taken from him. These mild measures, however, were in vain; the Meletians joined the Arians and caused more dissension than ever, being among the worst enemies of Athanasius. The Meletians ultimately died out around the middle of the fifth century.

Other problems

Finally, the council promulgated 20 new church laws, called canons (though the exact number is subject to debate[29]), that is, unchanging rules of discipline. The 20 as listed in the Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers are as follows:[30]

- 1. prohibition of self-castration (see Origen)

- 2. establishment of a minimum term for catechumen;

- 3. prohibition of the presence in the house of a cleric of a younger woman who might bring him under suspicion;

- 4. ordination of a bishop in the presence of at least three provincial bishops and confirmation by the metropolitan;

- 5. provision for two provincial synods to be held annually;

- 6. exceptional authority acknowledged for the patriarchs of Alexandria and Rome, for their respective regions;

- 7. recognition of the honorary rights of the See of Jerusalem;

- 8. provision for agreement with the Novatianists;

- 9–14. provision for mild procedure against the lapsed during the persecution under Licinius;

- 15–16. prohibition of the removal of priests;

- 17. prohibition of usury among the clergy;

- 18. precedence of bishops and presbyters before deacons in receiving Holy Communion;

- 19. declaration of the invalidity of baptism by Paulian heretics;

- 20. prohibition of kneeling during the liturgy, on Sundays and in the fifty days of Eastertide ("the pentecost"). Standing was the normative posture for prayer at this time, as it still is among the Eastern Orthodox and Eastern Catholics. (In time, Western Christianity adopted the term Pentecost to refer to the last Sunday of Eastertide, the fiftieth day.)[31]

Effects of the Council

The long-term effects of the Council of Nicaea were significant. For the first time, representatives of many of the bishops of the Church convened to agree on a doctrinal statement. Additionally, for the first time, the Emperor played a role, by calling together the bishops under his authority, and using the power of the state to give the Council's orders effect.

In the short-term, however, the council did not completely solve the problems it was convened to discuss and a period of conflict and upheaval continued for some time. Constantine himself was succeeded by two Arian Emperors in the Eastern Empire: his son, Constantine II and Valens. Valens could not resolve the outstanding ecclesiastical issues, and unsuccessfully confronted Saint Basil over the Nicene Creed.[32] Pagan powers within the Empire sought to maintain and at times re-establish Paganism into the seat of Emperor. Arians and the Meletians soon regained nearly all of the rights they had lost, and consequently, Arianism continued to spread and to cause division in the Church during the remainder of the fourth century. Almost immediately, Eusebius of Nicomedia, an Arian bishop and cousin to Constantine I, used his influence at court to sway Constantine's favor from the orthodox Nicene bishops to the Arians. Eustathius of Antioch was deposed and exiled in 330 C.E. Athanasius, who had succeeded Alexander as Bishop of Alexandria, was deposed by the First Synod of Tyre in 335 C.E. and Marcellus of Ancyra followed him in 336 C.E. Arius himself returned to Constantinople to be readmitted into the Church, but died shortly before he could be received. Constantine died the next year, after finally receiving baptism from Arian Bishop Eusebius of Nicomedi.

Notes

- ↑ Philip Schaff. Schaff's History of the Christian Church, Volume III, Nicene and Post-Nicene Christianity, § 120. The Council of Nicaea, 325: "Only two Egyptian bishops, Theonas and Secundus, persistently refused to sign, and were banished with Arius to Illyria. The books of Arius were burned and his followers branded as enemies of Christianity." Christian Classics Ethereal Library. Retrieved June 25, 2008.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Richard Kieckhefer, (1989). "Papacy." Dictionary of the Middle Ages. (Charles Scribner's Sons. ISBN 0684182750)

- ↑ Warren H. Carroll. The Building of Christendom. (Christendom Press, (1987) 2004. ISBN 0931888247), 10

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Carroll, 11

- ↑ Eusebius of Caesaria, Life of Constantine (Book III) Chapter 9, Translated by Ernest Cushing Richardson. From Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Second Series, Vol. 1, Edited by Philip Schaff. (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1890), Revised and edited for New Advent by Kevin Knight. Newadvent.org. accessdate 2006-05-08

- ↑ Afros Epistola Synodica 2.newadvent.org. Retrieved February 18, 2009.

- ↑ Theodoret H.E. 1.7

- ↑ Socrates Scholasticus. [Historia Ecclesiasticus Book 1 Chapter VIII.—Of the Synod which was held at Nicæa in Bithynia, and the Creed there put forth. Christian Classics Ethereal Library.

- ↑ H.E. 3.31

- ↑ Hilarius. Contra Constantium (Ad Constantium Augustum liber secundus)

- ↑ Chronicon

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 12.6 12.7 Aziz S. Atiya. The Coptic Encyclopedia. (New York: Macmillan Publishing Company, 1991. ISBN 002897025X.)

- ↑ Philostorgius, in Photius, Epitome of the Ecclesiastical History of Philostorgius, book 1, chapter 9. tertullian.org.

- ↑ Philostorgius, in Photius, Epitome of the Ecclesiastical History of Philostorgius, book 1, chapter 9. tertullian.org.

- ↑ Philostorgius, in Photius, Epitome of the Ecclesiastical History of Philostorgius, book 1, chapter 9. tertullian.org.

- ↑ Philostorgius, in Photius, Epitome of the Ecclesiastical History of Philostorgius, book 1, chapter 9.

- ↑ Hans Lietzmann in Zeitschrift fur die Neutestamentliche Wissenschaft und die Kunde der alteren Kirch, XXIV (1925), 193-202.

- ↑ Carroll, 12

- ↑ The Latin version of the text adds "Deum de Deo" and "Filioque" to the Greek version, which became sources of the Filioque Controversy.

- ↑ Text in Armenian, with transliteration and English translation armenianchurchlibrary. Retrieved June 25, 2008.

- ↑ Socrates Church History Chapter IX. Christian Classics Ethereal Library. Retrieved June 25, 2008.

- ↑ Gaston du Fresne de Beaucourt. Revue des questions historiques, éditée par Victor Palmé. (Paris: 1866-1939), xxviii. 37

- ↑ Theodoret. Hist. eccl., I., ix. 12; Socrates, Hist. eccl., I., ix. 12

- ↑ Eusebius, Vita Constantine, III., xviii. 19; Theodoret, Hist. eccl., I., x. 3 sqq.

- ↑ De Synodo, v.; Epist. ad Afros, ii.

- ↑ Epiphanius. The Panarion of Epiphanius of Salamis, Books II and III, Sects 47-80; De Fide, Section VI, Verses 1,1 and 1,3., Translated by Frank Williams. (New York: E.J. Brill, 1994), 471-472).

- ↑ Philip Schaff.History of the Christian Church, Volume III: Nicene and Post-Nicene. Christian Classics Ethereal Library. accessdate 2006-05-08

- ↑

"Meletius" in the 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia.

"Meletius" in the 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia.

- ↑ Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Series II, Vol. XIV, Excursus on the Number of the Nicene Canons. Early Church Fathers accessdate 2006-05-08

- ↑ Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Series II, Vol. XIV, The Canons of the 318 Holy Fathers Assembled in the City of Nice (sic), in Bithynia.. Early Church Fathers accessdate 2006-05-08

- ↑ For the exact text of the prohibition of kneeling, in Greek and in English translation, see canon 20 of the acts of the council.

- ↑ Heroes of the Fourth Century. orthodoxresearchinstitute.org. Retrieved June 25, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Atiya, Aziz S. The Coptic Encyclopedia. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company, 1991. ISBN 002897025X.

- Carroll, Warren H. The Building of Christendom. Christendom Press, 2004 (original 1987). ISBN 0931888247

- Davis, S.J., Leo Donald, The First Seven Ecumenical Councils (325-787). 1983, ISBN 0814656161

- Kelly, J.N.D., "The Nicene Crisis." in Early Christian Doctrines. HarperOne, 1978, ISBN 006064334X

- Kelly, J.N.D., "The Creed of Nicea." in Early Christian Creeds, 3rd ed. Continuum, 2006 (original 1982). ISBN 0826492169.

- Kieckhefer, Richard. "Papacy." Dictionary of the Middle Ages. Charles Scribner's Sons. 1987. ISBN 0684182750

- Lietzmann, Hans. Zeitschrift fur die Neutestamentliche Wissenschaft und die Kunde der alteren Kirch. XXIV (1925), 193-202.

- Newman, John Henry, "The Ecumenical Council of Nicæa in the Reign of Constantine." from Arians of the Fourth Century. 1871.

- Rubenstein, Richard E., When Jesus Became God: The Epic Fight Over Christ's Divinity in the Last Days of Rome. Harcourt, 2003 (original 1999). ISBN 0151003688

- Rusch, William G. The Trinitarian Controversy. Sources of Christian Thought Series. Augsburg Fortress, 1980. ISBN 0800614100

- Tanner, S.J., Norman P., The Councils of the Church: A Short History. The Crossroad Publishing Company, 2001. ISBN 0824519043

- Theodoret, General Council of Nicæa Book 1 Chapter 6 of his Ecclesiastical History; The Epistle of the Emperor Constantine, concerning the matters transacted at the Council, addressed to those Bishops who were not present Book 1 Chapter 9 of his Ecclesiastical History, a 5th century source.

External links

All links retrieved March 28, 2024.

- Athanasius of Alexandria, The Council of Nicæa; To the Bishops of Africa

- Eusebius of Caesarea, Letter of Eusebius of Cæsarea to the people of his Diocese Account of the Council of Nicea; The Council of Nicæa.

- Philostorgius, Epitome of the Church History.

- Socrates, Of the Synod which was held at Nicæa in Bithynia, and the Creed there put forth Book 1 Chapter 8 of his Ecclesiastical History, 5th century source.

- Sozomen, Of the Council convened at Nicæa on Account of Arius Book 1 Chapter 17 of his Ecclesiastical History, a 5th century source.

- Theodoret, General Council of Nicæa Book 1 Chapter 6 of his Ecclesiastical History; The Epistle of the Emperor Constantine, concerning the matters transacted at the Council, addressed to those Bishops who were not present Book 1 Chapter 9 of his Ecclesiastical History, a 5th century source.

- The Council of Nicaea and the Bible. This article deals with the legend that the canon of the bible was discussed at the council.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.