| Bundesrepublik Deutschland Federal Republic of Germany |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Motto:Â Einigkeit und Recht und Freiheit (German for "Unity and Justice and Freedomâ) |

||||||

| Anthem:Â Das Lied der Deutschen (3rd stanza) |

||||||

| Capital (and largest city) | Berlin 52°31âČN 13°23âČE | |||||

| Official languages | German1 | |||||

| Government | Federal Republic | |||||

| Â -Â | President | Frank-Walter Steinmeier | ||||

| Â -Â | Chancellor | Friedrich Merz | ||||

| Formation | ||||||

| Â -Â | Holy Roman Empire | February 2, 962Â | ||||

| Â -Â | Unification | January 18, 1871Â | ||||

| Â -Â | Federal Republic | May 23, 1949Â | ||||

| Â -Â | Reunification | October 3, 1990Â | ||||

| EU accession | March 25, 1953 (West Germany) |

|||||

| Area | ||||||

|  - | Total | 357,021 kmÂČ (63rd) 137,847 sq mi |

||||

|  - | Water (%) | 2.416 | ||||

| Population | ||||||

| Â -Â | Q3 2024Â estimate | |||||

| Â -Â | 2022Â census | |||||

|  - | Density | 234/kmÂČ (58th) 606.1/sq mi |

||||

| GDPÂ (PPP) | 2025Â estimate | |||||

| Â -Â | Total | |||||

| Â -Â | Per capita | |||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2025Â estimate | |||||

| Â -Â | Total | |||||

| Â -Â | Per capita | |||||

| Gini (2024) | 29.5 [4] | |||||

| Currency | Euro (âŹ)2 (EUR) |

|||||

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) | |||||

|  - | Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) | ||||

| Internet TLD | .de3 | |||||

| Calling code | +49 | |||||

| 1 Danish, Low German, Sorbian, Romany, and Frisian are officially recognized and protected as minority languages by the ECRML. 2 Prior to 1999 (introduction of the euro as legal tender) and 2002 (introduction of the euro as physical notes and coins): Deutsche Mark. 3 The .eu domain is also used, as it is shared with other European Union member states. |

||||||

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, a country in Central Europe, is a modern great power, the world's third largest economy, and the world's largest exporter of goods.

Germany is a democratic parliamentary federal republic, historically consisting of several sovereign states with their own history, distinct German tribe dialects, culture, and religious beliefs. Germany was unified as a nation state amidst the Franco-Prussian War in 1871.

Known as a land of poets and thinkers, Germany has occupied a central position in the history of western civilization, as the location of the Holy Roman Empire, and the Protestant Reformation. The nation has emerged from the devastation of the great wars of the twentieth century, and division into free-world and communist-world territories, to become the European Union's most populous and most economically powerful member state.

Geography

Because of its central location, Germany shares borders with more European countries than any other country in Europe. Its neighbors are Denmark in the north, Poland and the Czech Republic in the east, Austria and Switzerland in the south, France and Luxembourg in the southwest, and Belgium and the Netherlands in the northwest. Germany is also bordered to the north by the North Sea and the Baltic Sea.

Total land area is 134,835 square miles (349,223 square kilometers), or slightly smaller than the state of Montana in the United States.

The territory of Germany stretches from the high mountains of the Alps, the highest point being the Zugspitze at 9,718 feet (2,962 meters), in the south, to the shores of the North Sea (Nordsee) in the northwest and the Baltic Sea (Ostsee) in the northeast. In between are the forested uplands of central Germany, and the low-lying lands of northern Germany. The lowest point is Neuendorfer/Wilstermarsch at 11.6 feet (3.54 meters) below sea level.

The greater part of Germany lies in the cool/temperate climatic zone in which humid westerly winds predominate. In the northwest and the north, the climate is oceanic and rain falls all year round. Winters there are relatively mild and summers tend to be comparatively cool, even though temperatures can reach above 86°F (30°C) for prolonged periods. Hamburg's average temperatures are 33°F (0.3°C) in January (winter) and 63°F (17.1°C) in July.

In the east, the climate shows clear continental features. Winters can be cold for long periods, and summers can become warm. Here, too, long dry periods are often recorded. Berlin's average temperatures for January are 30°F (â0.9°C), and 65°F (18.6°C) for July.

The three main rivers are the Rhine, with a German part 537 miles (865km) long, and main tributaries including the Neckar, the Main, and the Moselle; the Elbe, with a German part 452 miles (727km) long (which also drains into the North Sea); and the Danube, with a German part 427 miles (687km) long. Further important rivers include the Weser River and the Ems.

The largest lakes are Lake Constance (total area of 207 square miles (536kmÂČ), with 62 percent of the shore being German, MĂŒritz, and Chiemsee. Most of Germany is covered by either arable land (33 percent) or forest and woodland (31 percent). Only 15 percent is covered by permanent pastures.

Natural resources include iron ore, coal, potash, timber, lignite, uranium, copper, natural gas, salt, nickel, arable land, and water. Natural hazards include flooding.

The plants and animals are those common to middle Europe. Beeches, oaks, and other deciduous trees make up 30 percent of forests, with increasing areas of conifers as a result of reforestation. Spruce and fir trees grow in the upper mountains, while pine and larch grow in sandy soil. Deer, wild boar, mouflon, fox, badger, hare, and small numbers of beaver live in the wild.

The Black Forest area has the rare breed of HinterwÀlder cows, the giant earthworm Lumbricus badensis, and Black Forest Foxes, a breed of horse, previously indispensable for heavy field work. Eagles and owls can be seen at close range as they sweep overhead.

Environmental issues involve emissions from coal-burning utilities and industries that contribute to air pollution; acid rain, resulting from sulfur dioxide emissions, which damages forests; pollution in the Baltic Sea from raw sewage and industrial effluents from rivers in eastern Germany; and hazardous waste disposal. The government established a mechanism for ending the use of nuclear power over a period of 15 years, and was working to meet a European Union commitment to identify nature preservation areas in line with the EU's flora, fauna, and habitat directive.

Germany's capital is Berlin. Many of the governmental institutions and ministries, as well as embassies, were moved there from the former capital of West Germany, Bonn, in 1999. The five largest metropolitan areas are: Rhein-Ruhr with 11,785,196 inhabitants, Frankfurt Rhein-Main Region with 5,822,383, Berlin 4,262,480, Hamburg 3,278,635, and Stuttgart with 2,344,989 inhabitants.

Because of the country's federal and decentralized structure, Germany has a number of larger cities. The most populous are Berlin, with 3,396,990 inhabitants, Hamburg (1,744,215), Munich, Cologne, Frankfurt, and Stuttgart. The federal structure has kept the population oriented towards a number of large cities, and has precluded the growth of any single city that would rival such European capitals as London, Paris, or Moscow for size.

History

Stone Age

Wandering bands of hunters and gatherers including the species Heidelberg man populated German forests about 400,000 years ago. Skeletal finds near Steinheim are about 300,000 years old. Neanderthals, the remains of which were found near DĂŒsseldorf, lived about 100,000 years ago, and Cro-Magnons appeared by 40,000 B.C.E. Around 4500 B.C.E., farming peoples from southwest Asia migrated up the Danube Valley into central Germany. Known as the Danubian culture, these villagers lived with their animals in large, gabled wooden houses, made pottery, and traded with Mediterranean people for fine stone and flint axes and shells.

Bronze Age

People from the eastern Mediterranean began working copper and tin deposits in central Germany, Bohemia, and Austria around 2500 B.C.E. Around 2300 B.C.E., battleaxe-wielding Indo-Europeans, probably from southern Russia, settled in northern and central Germany, while Slavic peoples settled in the east, and Celts in the south and west. The Bell-Beaker people, who were skilled metalworkers, moved east from Spain and Portugal about the year 2000 B.C.E., and developed a thriving Bronze Age culture in Germany. From 1800 to 400 B.C.E., Celtic people in southern Germany and Austria developed the Urnfield, Hallstatt, and La TĂšne metalworking cultures, introduced the use of iron for tools and weapons, and used ox-drawn ploughs and wheeled vehicles.

Co-existence with the Roman Empire

Under Augustus (63 B.C.E. to 14 C.E.), the Roman General Publius Quinctilius Varus began to invade Germania (a term used by the Romans for territory from the Rhine to the Urals), and it was in this period that the Germanic tribes became familiar with Roman tactics of warfare. In 9 C.E., three Roman legions led by Varus were defeated by the Cheruscan leader Arminius in the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest. Modern Germany, as far as the Rhine and the Danube, thus remained outside the Roman Empire. By 100 C.E., the time of Tacitus' Germania, Germanic tribes settled along the Rhine and the Danube (the Limes Germanicus), occupying most of the area of modern Germany. The third century saw the emergence of a number of large West Germanic tribes: Alamanni, Franks, Chatti, Saxons, Frisians, Sicambri, and Thuringii.

In 376, the emperor Valens admitted Visigoths as allies to farm and defend the frontier. In the fourth and fifth centuries, nomadic Huns, sweeping in from Asia, set off waves of migration, during which the Ostrogoths, Visigoths, Vandals, Franks, Lombards, and other Germanic peoples overran the Roman Empire.

Christianization

The Roman provinces north of the Alps had been Christianized since the fourth century and dioceses such as that of Augsburg were maintained after the end of the Roman Empire. However, from around 600, Irish-Scottish monks founded monasteries at WĂŒrzburg, Regensburg, Reichenau, and other places. The missionary activity in the Merovingian kingdom was continued by the Anglo-Saxon monk Boniface (672â754), who established the first monastery east of the Rhine at Fritzlar. Bishoprics under papal authority were established.

Clovis unites Franks

Clovis I (c. 466 â 511) conquered neighboring Frankish tribes and established himself as sole king. He succeeded his father Childeric I in 481 as King of the Salian Franks, who occupied the area west of the lower Rhine, with their center around Tournai and Cambrai along the modern frontier between France and Belgium. Clovis converted to Roman Catholicism, as opposed to the Arianism common among Germanic peoples, at the instigation of his wife, the Burgundian Clotilda, a Catholic. He was baptized in the Cathedral of Rheims. This act was of immense importance in the subsequent history of France and Western Europe in general, for Clovis expanded his dominion over almost all of the old Roman province of Gaul (roughly modern France). He is considered the founder both of France (which his state closely resembled geographically at his death) and the Merovingian dynasty which ruled the Franks from the mid-fifth to the mid-eighth century. Merovingian rule was ended by a palace coup in 751 when Pippin the Short formally deposed Childeric III, beginning the Carolingian monarchy.

Charlemagne and the Holy Roman Empire

The Carolingian dynasty (known variously as the Carlovingians or Karlings) was a Frankish noble family with its origins in the Arnulfing and Pippinid clans of the seventh century. The name Carolingian itself comes from Charles Martel, who lived from 686 to 741 (from the Latin Carolus Martellus), who defeated the Moors at the Battle of Tours in 732. The greatest Carolingian monarch was Charlemagne (742 or 747 to 814), a champion of Christianity and supporter of the papacy. Charlemagne fought the Slavs south of the Danube, annexed southern Germany, and subdued and converted pagan Saxons in the northwest. Charlemagne had himself crowned Emperor by Pope Leo III at Rome in 800, an event which revived the Roman imperial tradition in the west, and set a precedent for the dependence of the emperors on papal approval. He is often seen as the Father of Europe and is an iconic figure, instrumental in defining European identity. His was the first truly imperial power in the West since the fall of Rome.

Latin was the official language of the court and the Church, although the West Franks in Gaul adopted the Latinate vernacular that became French. East Franks and other Germanic people spoke various languages that became German. Carolingian rulers encouraged missionary work among the Germans. Non-Frankish Germans, however, retained much pagan belief beneath their newly acquired faith.

The Carolingians had the practice of making their sons (sub-)kings in the various regions (regna) of the Empire, which they would inherit on the death of their father. They also followed the traditional Frankish (and Merovingian) practice of dividing inheritances among heirs, instead of passing everything to the eldest son (primogeniture). The Carolingians disallowed inheritance to illegitimate offspring.

Empire divided

Charlemagne's third son Louis the Pious (778â840) was Emperor and King of the Franks from 814 to his death in 840. The surviving adult Carolingians fought a three-year civil war ending in the Treaty of Verdun (843), which divided the empire among Charlemagne's three grandsons. One received West Francia (modern France), another acquired the imperial title and a territory extending from the North Sea to Italy, while the third, Louis the German (804â876), received East Francia (modern Germany). The Treaty of Mersen (870) divided the middle kingdom, with Lotharingia going to East Francia and the rest to West Francia. In 881, Charles the Fat (839â888) of East Francia, heir of Louis the German, received the imperial title. Six years later he was deposed by Arnulf of Carinthia (850â899), a bastard child of a legitimate Carolingian king, the last Carolingian emperor.

Tribal duchies

By the tenth century, pagan Danes, Magyars, and Moravians invaded East Francia from the north and east, while rival Frankish tribes fought. The Carolingians had granted lands as temporary fiefs to dukes (tribal military leaders), counts (appointed officials), and clergy for their services to the state. As central royal authority declined, feudal lords provided local government and defense, and the fiefs became hereditary. The five main duchies were Franconia, Swabia, Bavaria, Saxony, and Lorraine. Lesser warriors served dukes out of tribal loyalty and in exchange for grants of land. Common people lost the right to bear arms, and worked the fields in return for protection and a share of the crops. By ancient German tradition, the kings were elected, a system that delayed the emergence of a strong German state.

Saxon kings

The last Carolingian died without an heir, so the Franks and Saxons elected Conrad, Duke of Franconia (890â918), as their king, who proved incompetent. Next elected was the Saxon Duke Henry I (876â936), the Fowler, a sober, practical soldier, who made peace with a rival king, defeated Magyars and Slavs, and regained Lorraine. He united the Germanic peoples (Franks, Saxons, Swabians, and Bavarians) and for the first time, the term Kingdom (Empire) of the Germans (Regnum Teutonicorum) was applied to a Frankish kingdom, even though teutonicorum meant something closer to "Realm of the Germanic peoples."

Otto and Italy

In 936, Otto I the Great (912â973) was crowned at Aachen. He strengthened the royal authority by appointing bishops and abbots as princes of the Empire (ReichsfĂŒrsten), thereby establishing a national church (Reichskirche). Outside threats to the kingdom were contained with the decisive defeat of the Magyars of Hungary near Augsburg at the Battle of Lechfeld in 955 and the subjugation of Slavs between the Elbe and the Oder rivers. In 962, Otto I was crowned emperor in Rome, taking the succession of Charlemagne and establishing a strong Frankish influence over the papacy.

Otto became entangled in Italy, a rich land, and a scene of feudal disorder and Saracen invasions. When Adelheid, widowed queen of the Lombards, asked Otto for help against her captor, Berengar, King of Italy, Otto invaded Italy in 951, and married the widowed Queen, thereby winning the Lombard crown. Pope John XII appealed to Otto for aid against Berengar, so Otto invaded Italy a second time, defeated Berengar, and was crowned Emperor by the pope in 962. A treaty called the Ottonian Privilege guaranteed the popeâs claim to papal lands, while future papal candidates had to swear fealty to the emperor.

Otto II (955â983) established the Eastern March (Austria) as a military outpost, but he was defeated by the Saracens in his efforts to secure southern Italy. The pious Otto III (980â1002) attempted to revive the glory and power of ancient Rome with himself at the head of a theocratic state. He engineered the election of his cousin Bruno of Carinthia as Pope Gregory V, the first German pope.

The childless Henry II (972â1022), gentle and devout, encouraged the Cluniac movement and sent out missionaries from his court in the new bishopric of Bamberg. He was crowned King of Germany in 1002, and King of Italy in 1004. He was the only German king to be canonized.

Salian kings

The Salian dynasty was a dynasty in the High Middle Ages of four German Kings (1024â1125), also known as the Frankish dynasty after the family's origin and role as dukes of Franconia. All of these kings were also crowned Holy Roman Emperor (1027â1125). Under the reign of the Salian emperors, the Holy Roman Empire absorbed northern Italy and Burgundy.

Conrad II (990â1039), was a clever and ruthless ruler, who proved that the monarchy no longer depended on contracts between sovereign and territorial noblesâhe made the fiefs of lesser nobles hereditary, and appointed lower-class men responsible directly to him as officials and soldiers. He had Burgundy bequeathed to him, strengthened his hold on northern Italy, and had Poland return lands previously taken in conquest.

During the reign of Conradâs eldest son Henry III, the Black (1017â1056), the Holy Roman Empire supported the Cluniac reform of the Church, a series of changes within medieval monasticism focused on restoring the traditional monastic life, encouraging art, and caring for the poor, as well as the prohibition of simony (the purchase of clerical offices). Imperial authority over the Pope reached its peak. An imperial stronghold (Pfalz) was built at Goslar, as the Empire continued its expansion to the East.

Investiture controversy

A controversy began between Henry IV (1050â1106) and Pope Gregory VII (1025â1085) over appointments to ecclesiastical offices. Henry crushed a Saxon rebellion in 1075 and confiscated land, thus intensifying their hatred of him. When Gregory forbade lay investiture of churchmen, Henry had the Synod of Worms in 1076 depose him. The pope excommunicated Henry and freed his subjects from their oath of loyalty. The emperor was compelled to submit to the Pope at Canossa in 1077.

The princes elected a rival king, Rudolf of Swabia (1025â1080). In 1080, Gregory excommunicated Henry again and recognized Rudolf. Henry marched on Rome, deposed Gregory, installed the Antipope Clement III, and was crowned emperor in 1084. Henry returned to Germany to continue the civil war against a new rival king, since Rudolf had died in 1080. Finally, betrayed and imprisoned by his son Henry, the emperor was forced to abdicate.

Concordat of Worms

In 1122, a temporary reconciliation was reached between Henry V (1086â1125) and the pope with the Concordat of Worms, which stipulated German clerical elections would take place in the imperial presence without simony. The emperor was to invest the candidate with the symbols of his temporal office before a bishop invested him with the spiritual symbols. The consequences of the investiture dispute were a weakening of the Ottonian National Church, Reichskirche, and a strengthening of the Imperial secular princes.

Early medieval society

From 1100, new towns were founded around imperial strongholds, castles, bishops' palaces, and monasteries. The towns began to establish municipal rights and liberties, while the rural population remained in a state of serfdom. In particular, several cities became Imperial Free Cities, which did not depend on princes or bishops, but were directly subject to the emperor. The towns were ruled by patricians (merchants carrying on long-distance trade). Craftsmen formed guilds, governed by strict rules, which sought to obtain control of the towns. Trade with the east and north intensified. Germans colonized and chartered new towns and villages in largely Slav-inhabited territories east of the Oder, such as Bohemia, Silesia, Pomerania, Poland, and Livonia.

Hohenstaufen-Welf rivalry

Henry V died childless in 1125. His nephews Frederick and Conrad Hohenstaufen were passed over in favor of Lothair III of Supplinburg (1075â1137), Duke of Saxony. During his reign, a succession dispute broke out between the houses of Welf and Staufen; the latter was led by Frederick II and his brother Duke Conrad of Franconia. The Hohenstaufen, or Waiblingen, of Swabia, who were known as Ghibellines in Italy, held the German and imperial crowns, while the Welfs of Bavaria and Saxony, known as Guelphs in Italy, sided with the papacy. In Germany, Lothair fought a civil war with the Hohenstaufen princes, who refused to accept him as emperor. At Lothairâs death, the princes chose Conrad of Hohenstaufen (who reigned 1138â1152), and civil war erupted.

Frederick Barbarossa

Frederick I Barbarossa (1122â1190) was elected and crowned King of Germany in 1152, crowned King of Italy in 1154, Holy Roman Emperor in 1155, and King of Burgundy in 1178. Handsome and intelligent, warlike, just, and charming, Frederick Barbarossa was the ideal of the medieval Christian king. Regarding himself as the successor of Augustus, Charlemagne, and Otto the Great, he spent most of his reign shuttling between Germany and Italy trying to restore imperial glory in both.

An accommodation was reached with the rival Guelph party by the grant of the duchy of Bavaria to Henry the Lion (1129â1195), duke of Saxony. Austria became a separate duchy in 1156. Barbarossa tried to reassert his control over Italy, and in 1177 a final reconciliation was reached between the emperor and the Pope. In 1180, Henry the Lion was outlawed and Bavaria was given to Otto of Wittelsbach (founder of the Wittelsbach dynasty which was to rule Bavaria until 1918), while Saxony was divided.

From 1184 to 1186, the Hohenstaufen empire under Barbarossa reached its peak during the Reichsfest (imperial celebrations) held at Mainz and with the marriage of his son Henry in Milan to the Norman princess Constance of Sicily. The power of the feudal lords was undermined by the appointment of "ministerials" (unfree servants of the emperor) as officials. Chivalry and the court life flowered, leading to a development of German culture and literature.

Frederick died leading the Third Crusade. His son Henry VI (1165â1197) put down a rebellion by the returned exile Henry the Lion and then restored him to power, forced the northern Italian cities to submit to him, seized Sicily from a usurping Norman king, but died suddenly in 1197 while planning a crusade to the Holy Land. The empire fell apart.

Frederick II

Frederick II (1194â1250) was raised and lived most of his life in Sicily, his mother, Constance, being the daughter of Roger II of Sicily. He was known in his own time as Stupor mundi ("wonder of the world"), and was said to speak nine languages and be literate in seven. Frederick was a ruler very much ahead of his time, being an avid patron of science and the arts. Frederick II was a religious skeptic, which was unusual for the era in which he lived, and to his contemporaries, highly shocking and scandalous. Of his relations with the Saracens of Sicily, rather than exterminate them, he allowed them to settle on the mainland and build mosques. Not least, he enlisted them in hisâChristianâarmy and even into his personal bodyguards. His empire was frequently at war with the Papal States, so it is unsurprising that he was excommunicated twice and often vilified in chronicles of the time. Pope Gregory IX went so far as to call him the Antichrist. After his death the idea of his second coming where he would rule a 1000-year reich took hold, possibly in part because of this.

Between 1212 and 1250, he established a modern, professionally administered state in Sicily. He resumed the conquest of Italy, leading to further conflict with the papacy. In the Empire, extensive sovereign powers were granted to ecclesiastical and secular princes, leading to the rise of independent territorial states. The popes regarded Frederick as dangerous. When Frederick led a crusade to Jerusalem in 1228, Pope Gregory IX invaded Sicily. Frederick returned home and made peace, but by 1237 he battled the second Lombard League of cities that was allied with the pope. Frederick seized the Papal States, and the new pope, Innocent IV, fled to Lyon.

Frederick died peacefully, wearing the habit of a Cistercian monk, on December 13, 1250, in Castel Fiorentino near Lucera, in Puglia, after an attack of dysentery. His legitimate son Conrad IV inherited the Imperial and Sicilian crowns, but Conrad died four years later and the Hohenstaufen dynasty fell. There followed the Great Interregnum (1254â1273) between the end of Hohenstaufen rule and the beginning of Habsburg rule, during which there was no emperor.

Beginning in 1226 under the auspices of Emperor Frederick II, the Teutonic Knights began their conquest of Prussia after being invited to CheĆmno Land by the Polish Duke Konrad I of Masovia. The native Baltic Prussians were conquered and Christianized by the Knights with much warfare, and numerous German towns were established along the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea. From 1300, however, the Empire started to lose territory on all its frontiers.

Thirteenth-century society

The empire had lost Poland and Hungary by the late thirteenth century, and had lost control of Burgundy and Italy. Seven princes, whose principalities were virtually autonomous, chose weak kings. The Church was a dominant force in society. Towns paid taxes to the emperors in exchange for freedom from feudal obligations. Trade greatly increased. Towns began to form trade associations, the most powerful of which was the Hanseatic League. Rich burghers built city walls, cathedrals, and elaborate town halls and guildhalls. Lofty, richly decorated Gothic cathedrals were built in Bamberg, Strasbourg, Naumburg, and Cologne.

Three princely families vie for crown

By the late Middle Ages, the Habsburgs, Wittelsbachs, and Luxembourgs struggled for the imperial crown. The Great Interregnum ended in 1273, with the selection of Rudolf of Habsburg (1218â1291), a minor Swabian prince who made the Habsburgs one of the great powers in the empire. On Rudolfâs death the electors chose Adolf of Nassau (1255â1298), followed by Albert of Austria, then by Henry, Count of Luxembourg (1275â1313), who crossed the Alps in 1310 and temporarily subdued Lombardy. The Roman people crowned him, because the popes had left Rome and were living in Avignon, France, in the Avignon Papacy, the period from 1309 to 1377, during which seven French popes resided in Avignon.

Papal confirmation not required

Civil war raged until the Wittelsbach candidate, Louis IV the Bavarian (1282â1347), defeated his Habsburg rival at the Battle of MĂŒhldorf in 1322. The failure of negotiations between Emperor Louis IV and the papacy led in 1338 to the declaration at Rhense by six electors to the effect that election by all or the majority of the electors automatically conferred the royal title and rule over the empire, without papal confirmation. Between 1346 and 1378 Emperor Charles IV of Luxembourg, king of Bohemia, sought to restore the imperial authority. Around 1350, the Black Death ravaged Germany and most of Europe, killing about one-third of the population.

The Golden Bull

Pope Clement VI (1291â1351) opened negotiations with Charles IV, King of Bohemia (1316-1378), who was chosen in 1347. Charles IV, of the House of Luxembourg, ignored the question of papal assent. In the edict of the Golden Bull in 1356, which provided the basic constitution of the empire up to its dissolution, he specified the seven electors, made their lands indivisible, granted them monopolies on mining and tolls, and secured them âgiftsâ from candidates, making them the strongest princes. Charles entrenched his own dynasty in Bohemia, bought Brandenburg and took Silesia from Poland, and to obtain cash, he encouraged the silver, glass, and paper industries of Bohemia.

The Council of Constance and the Hussites

Emperor Sigismund (1368â1437), who was King of Bohemia, made John XXIII call the Council of Constance (1414â1418), to end the Papal schism which had resulted from the Avignon Papacy. (John XXIII, born Baldassarre Cossa [1370 â 1419], was antipope during the Western Schism.) The council was attended by roughly 29 cardinals, 100 "learned doctors of law and divinity," 134 abbots, 183 bishops and archbishops, and 1000 prostitutes. Bohemia was convulsed by the Hussite movement, which combined Czech nationalism with a desire for Church reform. Sigismund invited the Czech religious reformer Jan Hus (1369â1415) to state his views, under imperial protection, at the Council of Constance. But the council subsequently had him burned as a heretic, prompting the inconclusive Hussite Wars (1420â1434) against and among the followers of Hus in Bohemia.

The Habsburgs and German society

From 1438, the Habsburgs, who controlled most of the southeast of the empire (more or less modern-day Austria, Slovenia, Bohemia, and Moravia after the death of King Louis II in 1526), maintained a constant grip on the position of the Holy Roman Emperor until 1806.

Emperors included Albert II (1397â1439), who engaged in defending Hungary against the attacks of the Turks, died on October 27, 1439 at NeszmĂ©ly and was buried at SzĂ©kesfehĂ©rvĂĄr; and Frederick III (1415â1493). During his reign from 1493 to 1519, Maximilian I tried to reform the Empire: An Imperial Supreme Court (Reichskammergericht) was established, imperial taxes were levied, the power of the Imperial Diet (Reichstag) was increased. The reforms were frustrated by the continued territorial fragmentation of the empire, which gave rise to increased disunity among the empire's territorial rulers, and prevented the formation of nations in the manner of France and England.

Early-modern European society gradually came into being as a result of economic, religious, and political changes. Gradually, a proto-capitalistic system evolved out of feudalism. The Fugger family gained prominence through commercial and financial activities and became financiers to both ecclesiastical and secular rulers. The knightly classes found their monopoly on arms and military skill undermined by the introduction of mercenary armies and foot soldiers. Predatory activity by "robber knights" became common.

Luther and the Protestant Reformation

Martin Luther (1483â1546), a German monk, theologian, and church reformer, was particularly aroused by an unscrupulous campaign by the Church to sell indulgences, or remissions of punishment for sin. In 1517, Luther published a list of 95 theses attacking indulgences, and in 1520, he published his beliefs, which affirmed the liberty of the Christian conscience informed only by the Bible, a priesthood of all believers, and a State-supported Church. Pope Leo X (1475â1521) condemned Lutherâs works, and when Luther burned the papal condemnation, he was excommunicated. Charles V (1500â1558), who became Holy Roman Emperor in 1519, summoned Luther to defend himself at the Diet of Worms (1521). Luther refused to recant, so he was outlawed. Hiding in the Wartburg Castle, Luther translated the Bible, in so doing established the basis of the modern German language.

Luther's ideas spread rapidly. The fanatical theologian Andreas Karlstadt (1486â1541) urged iconoclastic attacks on church painting, statuary, and stained glass. The Peasants' War (1524â1526) broke out in Swabia, Franconia, and Thuringia against ruling princes and lords, following the preachings of Reformist priests. But the revolts, which were assisted by war-experienced noblemen like Götz von Berlichingen and Florian Geyer (in Franconia), and by the theologian Thomas MĂŒnzer (in Thuringia), were soon repressed by territorial princes. The peasants lost all rights and sense of initiative, and princes set up state churches in which the service was in German, and the clergy were allowed to marry.

Besides followers of Luther, Protestants were divided between Reformed Christians following Swiss theologian Ulrich Zwingli (1484â1531), who wanted to set up Bible-based theocratic states, and radical Anabaptists, poor people who wanted churches independent of the state. Without peaceful compromise, Charles V routed the Protestant princes and cities at the Battle of MĂŒhlberg in 1547. But many nobles, who had acquired Catholic lands and were staunch Protestants, forced on Charles V the Peace of Augsburg in 1555, which recognized the Lutheran faith, and stipulated that the religion of a state was to be that of its ruler.

The Catholic counter-reformation

The Council of Trent (1545â1563), an ecumenical council of the Catholic Church, abolished the sale of indulgences and reformulated doctrine and worship to preclude reconciliation with Protestantism. The Jesuit order, founded by the Spaniard Ignatius of Loyola (1491â1556), set up centers in German cities, and the rulers of Bavaria, Austria, Salzburg, Bamberg, and WĂŒrzburg restored Catholicism by force, creating a Catholic bloc in southern Germany. Protestant princes under Frederick IV (1574â1610) formed the Protestant Union in 1608, while in 1609, Maximilian I, Duke of Bavaria, led the Catholic princes into the Catholic League.

The Thirty Years War

The Thirty Years' War, fought between 1618 and 1648, was ostensibly a religious conflict between Protestants and Catholics, although the rivalry between the Habsburg dynasty and other powers was a more central motive. Catholic France under the de facto rule of Cardinal Richelieu supported the Protestant side in order to weaken the Habsburgs, thereby furthering France's position as the pre-eminent European power. This increased the France-Habsburg rivalry which led later to direct war between France and Spain. The war was fought principally on the territory of today's Germany, and involved most of the major European continental powers.

The Thirty Years' War, in which mercenary armies were extensively used, devastated entire regions scavenged bare by the foraging armies. Episodes of widespread famine and disease devastated the population of the German states and, to a lesser extent, the Low Countries and Italy, while bankrupting many of the powers involved.

The war ended with the Treaty of Mnster, a part of the wider Peace of Westphalia in 1648. The treaty recognized the independence of each Holy Roman Empire state, making the Holy Roman Emperor powerless. The prince of each German state would determine its religion, meaning that Habsburg lands and those to the south and west were Catholic. The treaty recognized the Reformed faith, and agreed that Protestants could retain acquired lands. But Germany had lost about one-third of its population to war, famine, and plague, as well as much of its livestock, capital, and trade. Refugees and mercenaries roamed, seizing what they could.

The rise of Prussia

From 1640, Brandenburg-Prussia had started to rise under the Great Elector of the House of Hohenzollern, Frederick William (1620â1688). The Peace of Westphalia in 1648 strengthened it even further, through the acquisition of East Pomerania. A system of rule based on absolutism was established. In 1701, Elector Frederick of Brandenburg was crowned "King in Prussia." From 1713 to 1740, King Frederick William I, also known as the "Soldier King," established a highly centralized state, with an efficient bureaucracy, which filled the treasury and paid for a large standing army. Meanwhile, the Wettins of Saxony became kings of Poland. The Welfs of Brunswick-LĂŒneburg gained great influence when Elector George inherited the throne of England as George I in 1714. The Wittelsbachs of Bavaria sought a crown in the Spanish Netherlands, and the Habsburgs of Austria held Bohemia and Hungary.

Wars with France, Sweden, Ottoman Turks

The German princes became involved in four wars with Franceâthe War of the Devolution (1667â1668), the Dutch War (1672â1678), the War of the League of Augsburg (1688â1697), which won Great Elector Frederick William of Brandenburg Strasbourg and Alsace, and the War of the Spanish Succession (1701â1714), which ended in the Peace of Utrecht. The German princes came into conflict with Sweden in the Baltic, in the First Northern War (1655-1660), and the Great Northern War (1700â1721).

In 1683, the Turks were defeated outside Vienna by a Polish relief army led by King Jan Sobieski of Poland while the city itself was defended by Imperial and Austrian troops under the command of Charles IV, Duke of Lorraine. Hungary was reconquered, and later became a new destination for German settlers. Austria, under the Habsburgs, developed into a great power.

The War of Austrian Succession

The War of Austrian Succession (1740â1748) began under the pretext that Maria Theresa of Austria was not eligible to succeed her father, Charles VI, Holy Roman Emperor, as ruler of the extensive Habsburg domains because Salic law precluded royal inheritance by a woman. The Bavarians, Saxons, and French invaded Austria and Bohemia, while Great Britain, the Netherlands, and Russia came to the aid of Austria. Frederick IIâs military victories prompted Maria Theresa to make peace with him in 1742, ceding him Silesia. Austria and its allies drove the French from Bohemia and conquering Bavaria. By the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle (1748), Maria Theresaâs husband, Francis, Duke of Lorraine, was recognized as emperor (although she ruled), and Maria Theresa gave up Bavaria and let Prussia keep Silesia.

But in the three Silesian Wars (1740â1763) and in the Seven Years' War (1756â1763) she had to cede Silesia to Frederick II, the Great, of Prussia. After the Peace of Hubertsburg in 1763 between Austria, Prussia, and Saxony, Prussia became a European great power. This started the rivalry between Prussia and Austria for the leadership of Germany.

Enlightened absolutism

"Enlightened absolutism" was established in Prussia and Austria starting in 1763. The ruler was to be "the first servant of the state." Frederick II, the Great (1712â1786), a proponent of the revised absolutism, modernized the Prussian civil service and promoted religious toleration. Frederick patronized the arts and philosophers. Reforms included the abolition of torture, improvement in the status of Jews, emancipation of peasants, while education was promoted. In the eighteenth century, after the religious wars and Turkish threat, German culture flowered. The princes centralized their governments, established mercantile economies, and built palaces, churches, museums, theaters, gardens, and universities. Burghers and peasants were scorned as uncouth, and useful only for paying taxes. Enlightenment theories of representative government, combined with Romantic ideas of freedom and national identity, fostered a desire for national unification.

Napoleonic wars

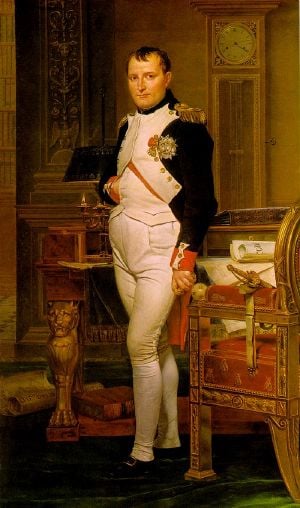

The French Revolution (1789â1799) was a period of political and social upheaval in France and Europe, during which the French government structure, previously an absolute monarchy with feudal privileges for the aristocracy and Catholic clergy, underwent radical change to forms based on Enlightenment principles of republic, citizenship, and inalienable rights.

This revolution sparked five wars of defense between the well-trained armies of Napoleonic France and neighbors including Prussia and Austria. Following the first two wars, the Peace of Basel in 1795 ceded the left bank of the Rhine to France. In the third, Napoleon conquered Vienna and Berlin. In 1803, Napoleon I of France (1769â1821) abolished almost all the ecclesiastical and the smaller secular German states and most of the imperial free cities. New medium-sized states were established in southwestern Germany. In turn, Prussia gained territory in northwestern Germany.

The Holy Roman Empire was formally dissolved on August 6, 1806, when the last Holy Roman Emperor, Francis II (1768â1835), resigned. In 1806 the Confederation of the Rhine was established under Napoleon's protection. In 1809, Austria led a fourth war against France, while Napoleon was occupied in Spain, but lost more land. In 1813, the Wars of Liberation began, following the destruction of Napoleon's army in Russia (1812). After the Battle of the Nations at Leipzig, in October 1813, Germany was liberated from French rule, and the Confederation of the Rhine was dissolved.

Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna was a conference between ambassadors from the major powers in Europe that was chaired by the Austrian statesman Klemens Wenzel von Metternich and held in Vienna, Austria, from late September, 1814, to June 9, 1815. Its purpose was to settle issues and redraw the continent's political map after the defeat of Napoleonic France the previous spring, which would also reflect the change in status caused by the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire eight years before. The discussions continued despite the ex-Emperor Napoleon I's return from exile and resumption of power in France in March 1815, and the Congress's Final Act was signed nine days before his final defeat at Waterloo on June 18, 1815, by Britain's Duke of Wellington and by Prussia's Gebhard Leberecht von BlĂŒcher.

German Confederation

The German Confederation was an association of 39 Central European states created by the Congress of Vienna in 1815 to serve as the successor to the 240-state Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation, which had been abolished in 1806. Its states were represented by a powerless legislature, known as a diet. Disagreement with the restoration politics led to a liberal movement seeking a government on British and French models, with a constitution guaranteeing popular representation, trial by jury, and free speech, along with national unification. However, the rulers of Prussia and Austria, and the kings of Bavaria, Hanover, WĂŒrttemberg, and Saxony, bitterly opposed liberalism and nationalism. Austria, Prussia, Russia, and Britain formed the Quadruple Alliance to resist any threat to the Vienna settlement.

On October 18, 1817, students held a gathering to exchange ideas, the high point of which was the burning of works by authors like August von Kotzebue, who were against a united German state. A second such meeting attracted 30,000 people from all social classes and regions to the Hambacher celebration. There for the first time, the colors of black, red, and gold were chosen to represent the movement, which later became the national colors. Meanwhile, the growing industrialization in Europe contributed to a wave of poverty, fueling social uprisings.

1848 revolutions

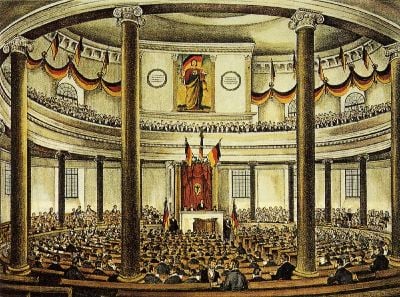

A July Revolution in Paris in 1830 set off uprisings in numerous German states. The confederation banned public meetings and petitions. In 1848, further revolutions, beginning in Paris, spread through Europe. Nationalist groups revolted in Hungary, Bohemia, Moravia, Galicia, Lombardy, Bavaria, Prussia, and southwest Germany. Metternich resigned and Emperor Ferdinand I (1793â1875) abdicated in favor of his nephew Francis Joseph I. In May, the German National Assembly (the Frankfurt Parliament) met in St. Paul's Church in Frankfurt am Main to draw up a national German constitution. But the 1848 revolution turned out to be unsuccessful. King Frederick William IV of Prussia refused the imperial crown, the Frankfurt parliament was dissolved, the ruling princes repressed the uprisings by military force, and the German Confederation was re-established by 1850.

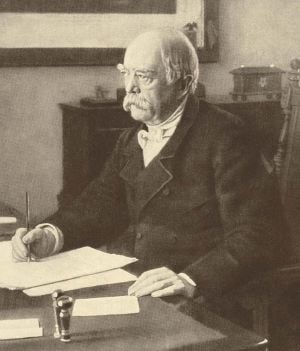

Bismarck appointed

In 1862, conflict between the Prussian King Wilhelm I and the increasingly liberal parliament erupted over military reforms. The king appointed Otto von Bismarck (1815â1898) the new Prime Minister of Prussia, who solved the conflict with difficulty and used the desire for national unification to further the interests of the Prussian monarchy. In 1863â64, disputes between Prussia and Denmark grew over Schleswig, whichâunlike Holsteinâwas not part of the German Confederation, and which Danish nationalists wanted to incorporate into the Danish kingdom. The dispute led to the Second War of Schleswig, in the course of which Prussia, joined by Austria, defeated Denmark. Denmark was forced to cede both the duchy of Schleswig and the duchy of Holstein to Austria and Prussia. In the aftermath, the management of the two duchies caused growing tensions between Austria and Prussia, which ultimately led to the Austro-Prussian War (1866). The Prussians were victorious in this war, carrying a decisive victory at the Battle of Königgratz.

North German Federation

In 1867, the North German Federation (German Norddeutscher Bund) under the leadership of Prussia replaced the German Confederation, which was dissolved in 1866. Austria was excluded, and would remain outside German affairs for most of the remaining nineteenth and the twentieth centuries. The North German Federation existed from 1867 to 1871, until the founding of the German Empire, led by Otto Von Bismarck who was declared chancellor. With it, Prussia established control over the 22 states of northern Germany and, via the Zollverein, southern Germany.

Franco-Prussian War

Differences between France and Prussia over the possible accession to the Spanish throne of a German candidateâwhom France opposedâwas the French pretext to declare the Franco-Prussian War (1870â71). Due to their defensive treaties, joint southern-German and Prussian troops repelled French troops which had occupied SaarbrĂŒcken and proceeded to invade France in August 1870. After a few weeks, the French army was forced to capitulate in the fortress of Sedan. French Emperor Napoleon III was taken prisoner and the Second French Empire collapsed. Months after the Siege of Paris was lifted, the Peace Treaty of Frankfurt was signed: France was obliged to cede what became known as Alsace-Lorraine to Germany.

German Empire proclaimed

During the Siege of Paris, the German princes assembled in the Hall of Mirrors of the Palace of Versailles and proclaimed the Prussian King Wilhelm I as the "German Emperor" on January 18, 1871. The German Empire was thus founded, with 25 states, three of which were Hanseatic free cities, and Bismarck, again, served as Chancellor. It was dubbed the "Little German" solution, since Austria was not included. Beginning in 1884 Germany established several colonies. The young emperor's foreign policy was opposed to that of Bismarck, who had established a system of alliances in the era called GrĂŒnderzeit, securing Germany's position as a great nation, isolating France using diplomatic means, and avoiding war for decades. Under Wilhelm II, however, Germany took an imperialistic course, not unlike other powers, but it led to friction with neighboring countries. Most alliances in which Germany had been previously involved were not renewed, and new alliances excluded the country. Specifically, France established new relations by signing the Entente Cordiale with the United Kingdom, and established ties with Russia. Austria-Hungary and Germany became increasingly isolated.

World War I

Although not one of the main causes, the assassination of Austria's crown prince helped trigger World War I on July 28, 1914, which saw Germany as part of the unsuccessful Central Powers in the second-bloodiest conflict of all time against the Allied Powers. The beginning of war was thus presented in authoritarian Germany as the chance for the nation to secure "our place under the sun" as the Kaiser Wilhelm II put it, which was readily supported by the prevailing nationalism of the public.

It soon became apparent that Germany was not prepared for a war lasting more than a few months. At first, little was done to regulate the economy for a wartime footing, and the German war economy would remain badly organized throughout the war. Germany depended on imports of food and raw materials, which were stopped by the British Naval blockade of Germany. Food prices were first limited, then rationing was introduced. The winter of 1916â17 was called "turnip winter." During the war, about 750,000 German civilians died from malnutrition. Even more died after the war, as the Allied blockade was not ended until the summer of 1919. In November 1918, the second German Revolution broke out, and Emperor Wilhelm II and all German ruling princes abdicated. An armistice was signed on November 11, putting an end to the war.

Treaty of Versailles

Germany was forced to sign the Treaty of Versailles in 1919. The treaty's unexpectedly high demands were perceived as humiliating in Germany, as a continuation of the war by other means, and as a break with traditional post-war diplomacy that included negotiations between the victors and vanquished. Germany was to cede Alsace-Lorraine, Eupen-MalmĂ©dy, North Schleswig, and the Memel area. Poland was restored and most of the provinces of Posen and West Prussia, and some areas of Upper Silesia were reincorporated into the reformed country after plebiscites and independence uprisings. All German colonies were to be handed over to the Allies. The left and right banks of the Rhine were to be permanently demilitarized. The industrially important Saarland was to be governed by the League of Nations for 15 years and its coalfields administered by France. At the end of that time a plebiscite was to determine the Saar's future status. To ensure execution of the treaty's terms, Allied troops would occupy the left (German) bank of the Rhine for a period of 5â15 years. The German army was to be limited to 100,000 officers and men; the general staff was to be dissolved; vast quantities of war material were to be handed over and the manufacture of munitions rigidly curtailed. The navy was to be similarly reduced, and no military aircraft were allowed. Germany and its allies were to accept the sole responsibility of the war, and were to pay financial reparations for all loss and damage suffered by the Allies.

Weimar Republic

After the German Revolution in November 1918, a Republic was proclaimed. That year, the German Communist Party was established by Rosa Luxembourg and Karl Liebknecht, and in January 1919 the German Workers Party, later known as the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (National Socialist German Workers Party, NSDAP, "Nazis"). On August 11, 1919, the Weimar Constitution came into effect, signed by ReichsprÀsident Friedrich Ebert.

In a climate of economic hardship from both the world-wide Depression and the harsh peace conditions dictated by the Treaty of Versailles, and a long succession of more or less unstable governments, the political masses in Germany increasingly lacked identification with their political system of parliamentary democracy. This was exacerbated by a wide-spread right-wing (monarchist, völkische, and Nazi) DolchstoĂlegende, a political myth which claimed the German Revolution was the main reason why Germany had lost World War I. On the other hand, radical left-wing communists such as the Spartacist League had wanted to abolish what they perceived as a "capitalist rule" in favor of a "RĂ€terepublik" and were thus also in opposition to the existing form of government.

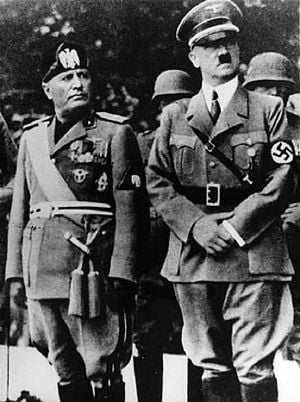

During the years following the Revolution, German voters increasingly supported anti-democratic parties, both right- (monarchists, Nazis) and left-wing (Communists). At the beginning of the 1930s, Germany was not far from a civil war. Paramilitary troops were set up by several parties, and there were thousands of politically motivated murders. They intimidated voters and seeded violence and anger among the public, who suffered from high unemployment and poverty. After a succession of unsuccessful cabinets, on January 29, 1933, President von Hindenburg, seeing little alternative and pushed by advisors, appointed Adolf Hitler Chancellor of Germany.

Nazi Germany

On February 27, 1933, the Reichstag was set on fire. Some basic democratic rights were quickly abrogated afterwards under an emergency decree. An Enabling Act gave Hitler's government full legislative powerâonly the Sozial Demokratische Partei, SPD voted against it; the communists could not because many had already been imprisoned or murdered. A centralized totalitarian state was established by a series of moves and decrees making Germany a single-party state. Industry was closely regulated with quotas and requirements in order to shift the economy towards a war production base. In 1936, German troops entered the demilitarized Rhineland and British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain's appeasement policies proved inadequate. Emboldened, Hitler followed from 1938 onwards a policy of expansionism to establish Greater Germany. To avoid a two-front war, Hitler concluded the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact with the Soviet Union.

World War II

In 1939 the growing tensions from nationalism, militarism, and territorial issues led to the Germans launching a blitzkrieg on September 1 against Poland, followed two days later by declarations of war by Britain and France, marking the beginning of World War II. Germany quickly gained direct or indirect control of the majority of Europe. On June 22, 1941, Hitler broke the pact with the Soviet Union by opening the Eastern Front and invading the Soviet Union. Shortly after Japan attacked the American base at Pearl Harbor, Germany declared war on the United States. Although initially the German army rapidly advanced into the surprised Soviet Union, the Battle of Stalingrad marked a turning point in the war. Subsequently, the German army commenced retreating on the Eastern front, followed by the eventual defeat of Germany. On May 8, 1945, Germany surrendered after the Red Army occupied Berlin.

In what later became known as The Holocaust, the Third Reich regime enacted governmental policies directly subjugating many parts of society: Jews, Slavs, Roma, homosexuals, freemasons, political dissidents, priests, preachers, religious opponents, and the disabled, amongst others. During the Nazi era about 11 million people were murdered in the Holocaust, including more than six million Jews.

East and West Germany

The war resulted in the death of millions of German soldiers and civilians, in total nearly 10 million, large territorial losses and the expulsion of about 15 million Germans from the eastern provinces of Germany and various parts of Central and Eastern Europe with ethnic German population. All major and many smaller German cities lay in ruins. Germany and Berlin were occupied and partitioned by the Allies into four military occupation zones controlled by France, the United Kingdom, the United States, and the Soviet Union. On May 23, 1949, the U.S., Britain, and France united their individual sectors to form the democratic nation of the Federal Republic of Germany and on October 7, 1949, the Soviet Zone established the German Democratic Republic. In English the two states were known informally as "West Germany" and "East Germany" (with historical eastern Germany having fallen to Poland and the Soviet Union) respectively.

West Germany, established as a liberal parliamentary republic with a "social market economy," was allied with the United States, the UK, and France. After the ideological switch in U.S. occupation policy away from economic dismantlement and towards reconstruction, which was heralded by the "Speech of Hope" in September of 1946, the country eventually came to enjoy prolonged economic growth beginning in the early 1950s (Wirtschaftswunder). The recovery was largely because of the previously forbidden currency reform of June 1948 and U.S. assistance through the Marshall Plan.

West Germany joined NATO in 1955 and was a founding member of the European Economic Community in 1958. Across the border, East Germany was at first occupied by and later (May 1955) allied with the USSR. An authoritarian country with a Soviet-style command economy, East Germany soon became the richest, most advanced country in the Warsaw Pact, but many of its citizens looked to the West for political freedoms and economic prosperity. Relations between East Germany and West Germany remained icy until the West German Chancellor Willy Brandt launched a highly controversial approachment policy with the East European communist states (Ostpolitik) in the early 1970s. This led to a form of mutual recognition between East and West Germany.

German reunification

During the summer of 1989, rapid changes took place in East Germany, which ultimately led to German reunification. Growing numbers of East Germans migrated to West Germany via Hungary and clandestinely through the border separating East from West Germany. The exodus generated demands within East Germany for political change, and mass demonstrations involving eventually hundreds of thousands of people in several cities continued to grow. In the face of these events, East German authorities unexpectedly eased the border restrictions in November 1989, allowing East German citizens to travel to the West. This led to the acceleration of the process of reforms in East Germany which ended with German reunification on October 3, 1990. Under the terms of the treaty between West and East Germany, Berlin again became the capital of the reunited Germany.

Since World War II, Germany has sustained intermittent turmoil from various groups. In the 1970s leftist terrorist organisations like the Red Army Faction engaged in a string of assassinations and kidnappings against political and business figures. Later, there was a surge in right-wing nationalist crimes. According to former Interior Minister Otto Schily, the number of these crimes rose 8.4 percent to 12,553 cases in 2004, which the minister attributed to such crimes as the display of illegal Nazi symbols being reported more frequently.

Some German states have banned Muslim teachers from wearing headscarves in class and all except Bavaria have banned crosses from the classroom as well, generally by prohibiting the use of all religious symbols by teachers. This results in a legal dilemma: According to the principle of separation of church and state, teachers in state schools are obliged to maintain religious neutrality, whereas pupils have a right to religious freedom and thus they cannot be restricted by such bans.

Government and politics

Constitutional structure

Germany is a federal parliamentary representative democratic republic, whereby the Chancellor is the head of government, and of a pluriform multi-party system. Executive power is exercised by the government. Federal legislative power is vested in both the government and the two chambers of parliament, the Bundestag and Bundesrat.

The German head of state is the President of Germany, elected by a federal convention. consisting of Bundesrat and Bundestag for a five-year term, and is eligible for a second term. The second highest official in the German order of precedence is the President of the Bundestag elected by the Bundestag itself. He is responsible for the parliament's sessions and the regularity of the institution. The third highest official is the chancellor as the head of government recommended by the President of Germany, and is elected by an absolute majority of the Bundestag for a four-year term.

The bicameral parliament consists of the Bundestag (federal assembly) and Bundesrat (federal council). The Bundestag comprises 614 seats elected by popular vote under a system combining direct and proportional representation to serve four-year terms. A party must win five percent of the national vote or three direct mandates to gain proportional representation and caucus recognition. The Bundesrat directly represents state governments; each has three to six votes depending on population and are required to vote as a block, with a total of 69 votes.

The political system is laid out in the 1949 constitutional document under approval of the allied forces which wanted to assure among other restrictions that Germany's military forces are restricted exclusively to defense and that a dictatorship could not reoccur. It is known as the Grundgesetz, literally "Basic Law." It is akin to the American Constitution. Changes in the Grundgesetz require a majority of two thirds of both chambers of the parliament. The Grundgesetz remained in effect with minor amendments after 1990s German Reunification.

Since 1949, the party system is dominated by the conservative Christian Democratic Union and the Social Democratic Party of Germany. Smaller parties that have an important role are the liberal Free Democratic Party, which has been in the Bundestag since 1949, as well as the Green Party which has had seats in the parliament since 1983.

The Judiciary of Germany is independent of the executive and the legislature. Germany has a civil or statute law system based ultimately on Roman law with some references to Germanic law. Legislative power is divided between the Federation and the individual federated states. While criminal law and private law have seen codifications on the national level, no such unifying codification exists in administrative law where a lot of the fundamental matters remain in the jurisdiction of the individual federated states. There are a series of special supreme courts; for civil and criminal cases the highest court of appeal is the Bundesgerichtshof (Federal Court of Justice), located in Karlsruhe. The courtroom style is inquisitorial.

The Federal Constitutional Court, also located in Karlsruhe, is the German Supreme Court responsible for constitutional matters, with power of judicial review. It acts as the highest legal authority and ensures that legislative and judicial practice conforms to the Constitution. It acts independently of the other state bodies, but cannot act on its own behalf.

Germany is divided into 16 states (in German called LÀnder). It is further subdivided into 439 districts (Kreise) and cities (kreisfreie StÀdte) (2004).

Foreign relations

Since reunification, Germany has resumed its role as a major central country between Scandinavia in the north and the Mediterranean region in the south, as well as between the Atlantic to the west and the countries of Central and Eastern Europe. Germany plays a leading role in the European Union, having a strong alliance with France. Germany is at the forefront of European states seeking to advance the creation of a more unified and capable European political, defense, and security apparatus.

Since its establishment on May 23, 1949, the Federal Republic of Germany kept a notably low profile in international relations, because of both its involvement in the world wars of the twentieth century, and its occupation by foreign powers. In 1999, however, on the occasion of the NATO war against Yugoslavia, Chancellor Gerhard Schröder's government sent German troops into combat for the first time since World War II.

Germany and the United States have been close allies since the end of the Second World War. The Marshall Plan and continued US support during the rebuilding process after World War II, as well as the significant influence American culture has had on German culture, crafted a strong bond between Germany and the US. Not only do the United States and Germany share many cultural similarities; they are also deeply economically interdependent. German-Americans are the largest ethnic group in the US, and the status of Ramstein Air Base, close to the city of Kaiserslautern, Germany, has the largest US community outside the US.

Armed forces

Germany's military, the Bundeswehr, is a defense force with Heer (German Army), Marine (German Navy), Luftwaffe (German Air Force), Zentraler SanitĂ€tsdienst (Central Medical Services), and StreitkrĂ€ftebasis (Joint Service Support Command) branches. It employed some 250,000 soldiers (including women in active fighting branches since 2001) and 120,000 civilians. About 40,000 of the soldiers are 18â23-year-old men on national duty, for at least nine months. In peacetime, the Bundeswehr is commanded by the Minister of Defense. If Germany goes to war, which according to the constitution is allowed only for defensive purposes, the Chancellor becomes commander-in-chief.

The German military had, in 2007, about 1,180 troops stationed in Bosnia-Herzegovina; 2,650 Bundeswehr soldiers were serving in Kosovo; 780 soldiers stationed as a part of EUFOR in the Democratic Republic of the Congo; 2,400 soldiers in a navy battle group off the coast of Lebanon as a part of UNIFIL, and 3,900 Bundeswehr troops assisted the US anti-terrorism operation called Enduring Freedom off the Horn of Africa. A total of 4,500 German troops made up the largest contingent of the NATO-led ISAF force in Afghanistan.

Energy policy

In the year 2000, the German SPD-led government announced its intention to phase out the use of nuclear energy, and reached an agreement with energy companies on limiting the life span of the existing nuclear power plants and an end to the civil usage of nuclear power by 2020.

In 1999, electricity production in Germany was powered by coal (47 percent), nuclear power (30 percent), natural gas (14 percent), renewable sources (including hydro, wind, and solar power) (6 percent), and oil (2 percent). As for energy consumption, oil accounted for 41 percent of the total. At the World Climate Conference, the German government announced a carbon dioxide reduction target of 25 percent by the year 2005 as compared to 1990, to protect global climate, and committed to a 21 percent reduction in carbon dioxide emissions from 1990 levels by 2012.

In 2005, the German government reached an agreement with Russia in building a gas pipeline along the bottom of the Baltic Sea directly from Russia to Germany. Bypassing Poland and other Baltic countries led to controversy.

Due in part to generous subsidies, Germany leads Europe by having the greatest capacity on the continent to generate electricity from sun and wind. By 2005 German solar electricity capacity had reached 794 MWp (78.6 percent of total European capacity), while wind generating capacity had reached 16,629 MWp (48.4 percent of European capacity).

In terms of total installed capacity to generate electricity from windpower, Germany is No.1 in the world. By 2005 it had a capability to generate 18,427.5 MW (in comparison: Second place Spainâ10,027 MW; third place USAâ9,141 MW). Because of the whims of wind and sun and the reluctance of the conventional energy companies to transmit renewable energy on their transmission lines, the power actually generated seldom reaches the capacity to produce it. Since the environmentalists have been voted out of government and the subsidies ended in 2006, the number of new wind generators to be installed in Germany has dropped dramatically. However, Germany's emphasis on renewable energy sources has resulted in the founding of numerous high-tech companies developing such technologies. Germany is also the main exporter of wind turbines, the demand greatly exceeding capacity.

Economy

The German social market economy helped bring about the "economic miracle" that rebuilt Germany from rubble after World War II to one of the most impressive economies in Europe. Today, Germany has the largest European economy.

Unemployment

A major concern remains the persistently high unemployment rate. When the five new federal states of East Germany joined the Federal Republic of Germany in 1990, unemployment worsened. East Germany lost its protected markets, its industry collapsed, and hundreds of thousands lost their jobs. However, Germany's unemployment rate is only partly comparable to rates in the United Kingdom or United States, because it includes numerous part-timers, who work fewer than 15 hours a week. Also, the percentage of so called "long-term sick" in Germany is lower than in the United Kingdom, Sweden, or the United States, countries with low official unemployment rates. Financial support for sickness in these countries normally lasts longer, is easier to obtain, or is higher than aid for unemployment.

Eastern Germany in particular suffers from a lack of a solid base of small and medium-sized companies, which provided the foundation for the Federal Republic's economic prosperity and is responsible in great measure for Germany's lag in economic growth. In spite of its extremely good performance in international trade, domestic demand has stagnated for many years because of wage stagnation and zealous cost-cutting by the federal state. Insecurity among consumers has caused many of the prevalent economic problems.

Exports

Like many other export-oriented countries, Germany does not have the climate or the natural resources necessary to support a high standard of living. Although most of its exports are in engineering (such as cars, machinery, chemical goods, and optics), Germany also has a strong position in the export of microelectronics.

Export commodities include machinery, vehicles, chemicals, metals and manufactures, foodstuffs, and textiles. Export partners include France, US, UK, Italy, Netherlands, Belgium, Austria, and Spain.

Import commodities include machinery, vehicles, chemicals, foodstuffs, textiles, and metals. Import partners included Netherlands,, France, Belgium, UK, China, Italy, US, Austria, and Russia.

Transport

Because of Germany's central location, the volume of traffic, especially goods transit, is very high. In the past decades, much of the freight traffic shifted from rail to road transport, which led the Federal Government to introduce a motor toll for trucks in 2005. In addition, individual traffic increased to an extent that on German roads, traffic densities are very high by international comparison.

High-speed vehicular traffic has a long tradition in Germany, not only owing to the automobile industry, but also because the first motorway (Autobahn) in the world, the AVUS, and the world's first automobile were developed and built by Carl Benz in Germany. Germany possesses one of the densest road systems of the world. It covers 12,037 kilometers (7,479 mi) of federal "Autobahn" motorways and 41,386 kilometers (25,716 mi) of federal highways. In contrast to other European countries, German motorways partially have no blanket speed limit. However, signposted limits are in place on many dangerous or congested stretches, and where traffic noise or pollution poses a nuisance.

Deutsche Bahn (German Rail) is the major German railway operator. For commuter and regional services, franchises of various sizes are granted by the individual states, though largely financed from the federal budget. Unsubsidized long-range service operators can compete freely all over the country, at least in theory. Actually, Deutsche Bahn holds a de facto monopoly on long-range services.

The InterCity Express or ICE is a type of high-speed train operated by Deutsche Bahn in Germany and neighboring countries, for example to ZĂŒrich, Switzerland or Vienna, Austria. ICE trains also serve Amsterdam (The Netherlands) as well as LiĂšge and Brussels (Belgium). In spite of branch lines progressively being closed, the rail network throughout Germany is still very extensive. On regular lines, at least one train every two hours will call even in the smallest of villages. A large proportion of towns feature underground and/or tram systems. Good urban and overland bus services are ubiquitous.

Frankfurt International Airport is an international airport and European transportation hub. Frankfurt Airport ranks among the world's top ten airports and serves 304 flight destinations in 110 countries. Germany's second important international airport is Munich International Airport.

Demographics

Germany is the most populous country in the European Union, the second most populous country in Europe after Russia. Germany it has witnessed increased birth rates and migration rates since the beginning of the 2010s, particularly a rise in the number of well-educated migrants.

Four sizable groups of people are referred to as "national minorities" because their ancestors have lived in their respective regions for centuries. There is a Danish minority (about 50,000) in the northernmost state of Schleswig-Holstein. The Sorbs, a Slavic population of about 60,000, are in the Lusatia region of Saxony and Brandenburg. The Roma and Sinti live throughout the whole federal territory and the Frisians live on Schleswig-Holstein's western coast, and in the north-western part of Lower Saxony.

Ethnicity

The official statistics, which collect only nationality data, show that Germans comprise 91.5 percent, Turks 2.4 percent, and others 6.1 percent (made up largely of Italians, Serbs, Croats, Bosnians, Greeks, Poles, Vietnamese, and Russians). While most of the German citizens are ethnic Germans (67.1 million or 81.4 percent) or naturalized immigrants (15.3 million or 18.6 percent), there are four other sizable "national minorities" that have lived in Germany for centuries. They are: Danes (about 50,000 in the northern-most state of Schleswig-Holstein), Frisians (60,000 in Schleswig-Holstein's western coast, and in the northwestern part of Lower Saxony ), Roma and Sinti, and Sorbs, a Slavic people with about 60,000 members.

Roma people have been in Germany since the Middle Ages. Thousands of Roma living in Germany were killed by the Nazi regime. Nowadays, they are spread all over Germany, mostly living in major cities. They could number about 70,000. In the 1990s, many Roma moved to Germany from former Yugoslavia. In contrast to the old-established Roma population, the majority of them do not have German citizenship; they are classified as immigrants or refugees.

After World War II, there was an influx of 14 million ethnic Germans from Eastern Europe who were expelled or fled after Germany lost the war. Since the 1960s, ethnic Germans from the Soviet Union have come to Germany, especially from Kazakhstan, Russia, and Ukraine. During the time of Perestroika (restructuring), and after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the number of immigrants increased heavily. Some of these immigrants are of mixed heritage.

Germany now has Europe's third-largest Jewish population. In 2004, twice as many Jews from former Soviet republics settled in Germany as in Israel, bringing the total inflow to more than 200,000 since 1991. Jews have a voice in German public life through the Zentralrat der Juden in Deutschland. Some Jews from the former Soviet Union are of mixed heritage.

There are also around 100,000 Afro-Germans and 150,000-plus African nationals as well as nearly 50,000 Indian-Germans.

Religion

Christianity is the largest religion in Germany with approximately half of the population identifying as either Protestant or Catholic. The second largest religion is Islam, followed by Buddhism and Judaism. There are also a smaller number of Hindus. The third largest religious identity in Germany, after the two Christian groups, is that of non-religious people (including atheists and agnostics [especially in former GDR]).

Germany is the home of the Protestant Reformation launched by Martin Luther in the early sixteenth century. Today, Protestants (particularly in the north and east) and Roman Catholics (particularly in the south and west) comprise similar proportions of the population. The Roman Catholic Pope, Benedict XVI, was born in Bavaria.

The three million Muslims (predominantly from Turkey and some from the former Yugoslavia) are mostly Sunnis and Alevites from Turkey but there are also a small number of Shiites. Some German cities have seen a revival of Jewish culture, particularly in Berlin, where there are also 3,000 Israelis. Other cities with significant Jewish populations are Frankfurt and Munich.

Language

German is Germany's only official and most widely spoken language. English is the most common foreign language and almost universally taught by the secondary level. Two-thirds of Germany's citizens have at least basic knowledge of English. About 20 percent consider themselves to be speakers of French, followed by speakers of Russian (18 percent), Italian (6.1 percent), and Spanish (5.6 percent). The high number of Russian speakers is a result of the GDR's close relation to the Soviet Unionâmore than half of the Germans in the East speak Russian, compared to 5.5 percent in the western part of the country.

German is a member of the western branch of the Germanic family of languages, which in turn is part of the Indo-European language family. The major German dialect groups are High and Low German. Low German dialects, similar to Dutch, were spoken around the mouth of the Rhine and on the northern coast. Low German has been given the status of a minority language by the European Union, although it is less used today in the traditionally Low Germanâspeaking areas of northern Germany. High German, originally the language of the southern highlands, has dialects divided into middle and upper categories. Other dialects, which are very different from standard German, are spoken in Saxony, Bavaria, Rhineland-Palatinate, and Swabia. The Pennsylvania Dutch, spoken by the Amish, is derived from the dialect spoken in the Rhineland-Palatinate. The German language was once the lingua franca of central, eastern, and northern Europe. As a foreign language, German is the third most taught worldwide. It is also the second most-used language on the Internet after English.

Men and women