Cheese

Cheese is a dairy product produced in wide ranges of flavors, textures, and forms by coagulation of the milk protein casein. It comprises proteins and fat from milk (usually the milk of cows, buffalo, goats, or sheep). As many as 2,000 types of cheese exist and are produced in various countries. Their styles, textures, and flavors depend on the origin of the milk (including the animal's diet), whether they have been pasteurized, the butterfat content, the bacteria and mold, the processing, and how long they have been aged. Other ingredients may be added to some cheeses, such as black pepper, garlic, chives, or cranberries. Also, herbs, spices, or wood smoke may be used as flavoring agents.

Cheese is valued for its portability and high content of fat, protein, calcium, and phosphorus. Cheese is more compact and has a longer shelf life than milk, although how long it keeps depends on the type. Hard cheeses, such as Parmesan, last longer than soft cheeses, such as Brie or goat's milk cheese. Although cheese is a vital source of nutrition in many regions of the world and it is extensively consumed in others, its use is not universal. Nevertheless, the creation of cheese from milk is well recognized as a valuable development that occurred early in human history and continues to contribute to the well-being of humankind.

Etymology

The word cheese comes from Latin caseus,[1] from which the modern word casein is also derived. The earliest source is from the proto-Indo-European root *kwat-, which means "to ferment, become sour." That gave rise to cīese or cēse (in Old English) and chese (in Middle English). Similar words are shared by other West Germanic languages—West Frisian tsiis, Dutch kaas, German Käse, Old High German chāsi—all from the reconstructed West-Germanic form *kāsī, which in turn is an early borrowing from Latin.[2]

When the Romans began to make hard cheeses for their legionaries' supplies, a new word started to be used: formaticum, from caseus formatus, or "molded cheese" (as in "formed," not "moldy"). It is from this word that the French fromage, standard Italian formaggio, Catalan formatge, Breton fourmaj, and Occitan fromatge (or formatge) are derived.[3]

History

Origins

Cheese is an ancient food whose origins predate recorded history. There is no conclusive evidence indicating where cheesemaking originated, whether in Europe, Central Asia or the Middle East. Earliest proposed dates for the origin of cheesemaking range from around 8000 B.C.E., when sheep were first domesticated. The earliest evidence of cheesemaking in the archaeological record dates back to 5500 B.C.E. in what is now Kuyavia, Poland, where strainers coated with milk-fat molecules have been found.[4] and on the Dalmatian coast in Croatia where fatty residue pottery revealed evidence of fermented dairy products.[5] Shards of holed pottery thought to be cheese-strainers, dating back to roughly 8,000 years ago, were found in Urnfield pile-dwellings on Lake Neuchatel in Switzerland.[6]

Evidence of cheese dating to approximately 1200 B.C.E. (3200 years before present) was found in ancient Egyptian tombs.[7] The earliest ever discovered preserved cheese was found in the Taklamakan Desert in Xinjiang, China, dating back as early as 1615 B.C.E. (3600 years before present).[8]

Since animal skins and inflated internal organs have, since ancient times, provided storage vessels for a range of foodstuffs, it is probable that the process of cheese making was discovered accidentally by storing milk in a container made from the stomach of an animal, resulting in the milk being turned to curd and whey by the rennet, a complex set of enzymes produced in the stomachs of ruminant mammals. Chymosin, its key component, is a protease enzyme that curdles the casein in milk. There is a legend—with variations—about the discovery of cheese by an Arab trader who used this method of storing milk.[9] Observation that the effect of making cheese in an animal stomach gave more solid and better-textured curds may have led to the deliberate addition of rennet.

Cheesemaking may have begun independently of this method, by the pressing and salting of curdled milk to preserve it.

The earliest cheeses were likely quite sour and salty, similar in texture to rustic cottage cheese or feta, a crumbly, flavorful Greek cheese. Cheese produced in Europe, where climates are cooler than the Middle East, required less salt for preservation. With less salt and acidity, the cheese became a suitable environment for useful microbes and molds, giving aged cheeses their respective flavors.

Ancient Greece and Rome

Ancient Greek mythology credited Aristaeus with the discovery of cheese. Homer's Odyssey, from the eighth century B.C.E.) describes the Cyclops making and storing sheep's and goats' milk cheese:

So we entered the cave and gazed in wonder at all things there. The crates were laden with cheeses, and the pens were crowded with lambs and kids.[10]

Thereafter he sat down and milked the ewes and bleating goats all in turn, and beneath each dam he placed her young. Then presently he curdled half the white milk, and gathered it in wicker baskets and laid it away, and the other half he set in vessels that he might have it to take and drink, and that it might serve him for supper.[11]

The ancient Roman poet Virgil wrote of cheese, particularly in his poem Moretum (The Salad):

Near his hearth a larder hung from the ceiling; gammons and slices of bacon dried and salted were wanting, but old cheeses, their rounded surface pierced midway with rushes, were suspended in baskets of close-woven fennel.[12]

According to Pliny the Elder, cheese was an everyday food and cheesemaking had become a sophisticated enterprise by the time the Roman Empire came into being. He mentions Caseus Helveticus, a hard Sbrinz-like cheese produced by the Helvetii, one of the tribes living in Switzerland at the time.[13]

Pliny's Natural History devotes a chapter (XI, 97) to describing the diversity of cheeses enjoyed by Romans of the early Empire. He stated that the best cheeses came from the villages near Nîmes, but they did not keep long and had to be eaten fresh. Cheeses of the Alps and Apennines were as remarkable for their variety then as now. A Ligurian cheese was noted for being made mostly from sheep's milk, and some cheeses produced nearby were stated to weigh as much as a thousand pounds each. Goats' milk cheese was a recent taste in Rome, improved over the "medicinal taste" of Gaul's similar cheeses by smoking. Of cheeses from overseas, Pliny preferred those of Bithynia in Asia Minor.[14]

Post-Roman Europe

As Romanized populations encountered unfamiliar newly settled neighbors, bringing their own cheese-making traditions, their own flocks and their own unrelated words for cheese, cheeses in Europe diversified further, with various locales developing their own distinctive traditions and products. The advancement of the cheese art in Europe was slow during the centuries after Rome's fall. As long-distance trade collapsed, only travelers would encounter unfamiliar cheeses.

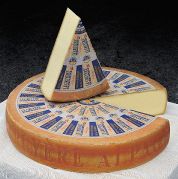

In 1022, it is mentioned that Vlach (Aromanian) shepherds from Thessaly and the Pindus mountains, in modern Greece, provided cheese for Constantinople.[15] Many cheeses popular today were first recorded in the late Middle Ages or after. Cheeses such as Cheddar around 1500, Parmesan in 1597, Gouda in 1697, and Camembert in 1791 show post-Middle Ages dates.[16]

Modern era

Until modern times cheese was popular only in Europe, the Middle East, the Indian subcontinent, and areas influenced by those cultures. Cheese was nearly unheard of in east Asian cultures and in the pre-Columbian Americas and had only limited use in sub-Mediterranean Africa. Today, however, cheese is popular worldwide.

The first factory for the industrial production of cheese opened in Switzerland in 1815, but large-scale production first found real success in the United States. Credit usually goes to Jesse Williams, a dairy farmer from Rome, New York, who in 1851 started making cheese in an assembly-line fashion using the milk from neighboring farms; this made cheese one of the first US industrial foods.[17] Within decades, hundreds of such commercial dairy associations existed.[18]

Late nineteenth century saw the beginnings of mass-produced rennet, and by the turn of the century scientists were producing pure microbial cultures. Before then, bacteria in cheesemaking had come from the environment or from recycling an earlier batch's whey; the pure cultures meant a more standardized cheese could be produced.[19]

Factory-made cheese overtook traditional cheesemaking in the World War II era, and factories have been the source of most cheese in America and Europe ever since.[20]

Processing

Cheese is a dairy product produced in wide ranges of flavors, textures, and forms by coagulation of the milk protein casein. It comprises proteins and fat from milk (usually the milk of cows, buffalo, goats, or sheep). During production, milk is usually acidified and either the enzymes of rennet or bacterial enzymes with similar activity are added to cause the casein to coagulate. The solid curds are then separated from the liquid whey and pressed into finished cheese. Some cheeses have aromatic molds on the rind, the outer layer, or throughout.

The craft of making cheese is called Cheesemaking (or "caseiculture"). Cheesemaking allows the production of the cheese with diverse flavors and consistencies.[13] The production of cheese, like many other food preservation processes, allows the nutritional and economic value of a food material, in this case milk, to be preserved in concentrated form.

The goal of cheese making is to control the spoiling of milk into cheese. Cheese is more compact and has a longer shelf life than milk, although how long a cheese will keep depends on the type of cheese. Hard cheeses, such as Parmesan, last longer than soft cheeses, such as Brie or goat's milk cheese.[21] The cheesemaker's goal is a consistent product with specific characteristics (appearance, aroma, taste, texture).

Over a thousand types of cheese exist and are produced in various countries. Their styles, textures and flavors depend on the origin of the milk (including the animal's diet), whether they have been pasteurized, the butterfat content, the bacteria and mold, the processing, and how long they have been aged. Herbs, spices, or wood smoke may be used as flavoring agents. The yellow to red color of many cheeses is produced by adding annatto. Other ingredients may be added to some cheeses, such as black pepper, garlic, chives, or cranberries. Some cheeses may be deliberately left to ferment from naturally airborne spores and bacteria; this approach generally leads to a less consistent product but one that is valuable in a niche market.[13]

For a few cheeses, the milk is curdled by adding acids such as vinegar or lemon juice. Most cheeses are acidified to a lesser degree by bacteria, which turn milk sugars into lactic acid, then the addition of rennet completes the curdling. Vegetarian alternatives to rennet are available; most are produced by fermentation of the fungus Mucor miehei, but others have been extracted from various species of the Cynara thistle family.[19]

Curdling

A required step in cheesemaking is separating the milk into solid curds and liquid whey. Usually this is done by acidifying (souring) the milk and adding rennet. The acidification can be accomplished directly by the addition of an acid, such as vinegar, in a few cases (paneer, queso fresco). More commonly starter bacteria are employed instead which convert milk sugars into lactic acid. The same bacteria (and the enzymes they produce) also play a large role in the eventual flavor of aged cheeses. Most cheeses are made with starter bacteria from the Lactococcus, Lactobacillus, or Streptococcus genera.[20] Swiss starter cultures also include Propionibacter shermani, which produces propionic acid and carbon dioxide gas bubbles during aging, giving Swiss cheese or Emmental its holes (called "eyes").[22]

Some fresh cheeses are curdled only by acidity, but most cheeses also use rennet. Rennet sets the cheese into a strong and rubbery gel compared to the fragile curds produced by acidic coagulation alone. It also allows curdling at a lower acidity—important because flavor-making bacteria are inhibited in high-acidity environments. In general, softer, smaller, fresher cheeses are curdled with a greater proportion of acid to rennet than harder, larger, longer-aged varieties. While rennet was traditionally produced via extraction from the inner mucosa of the fourth stomach chamber of slaughtered young, unweaned calves, most rennet used today in cheesemaking is produced recombinantly.[19]

Curd processing

At this point, the cheese has set into a very moist gel. Some soft cheeses are now essentially complete: they are drained, salted, and packaged. For most of the rest, the curd is cut into small cubes. This allows water to drain from the individual pieces of curd.

Some hard cheeses are then heated to temperatures in the range of 35–55 °C (95–131 °F). This forces more whey from the cut curd. It also changes the taste of the finished cheese, affecting both the bacterial culture and the milk chemistry. Cheeses that are heated to the higher temperatures are usually made with thermophilic starter bacteria that survive this step—either Lactobacilli or Streptococci.

Salt has roles in cheese besides adding a salty flavor. It preserves cheese from spoiling, draws moisture from the curd, and firms cheese's texture in an interaction with its proteins. Some cheeses are salted from the outside with dry salt or brine washes. Most cheeses have the salt mixed directly into the curds.

Other techniques influence a cheese's texture and flavor. Some examples are:

- Stretching: (Mozzarella, Provolone) the curd is stretched and kneaded in hot water, developing a stringy, fibrous body.

- Cheddaring: (Cheddar, other English cheeses) the cut curd is repeatedly piled up, pushing more moisture away. The curd is also mixed (or milled) for a long time, taking the sharp edges off the cut curd pieces and influencing the final product's texture.

- Washing: (Edam, Gouda, Colby) the curd is washed in warm water, lowering its acidity and making for a milder-tasting cheese.[23]

Most cheeses achieve their final shape when the curds are pressed into a mold or form. The harder the cheese, the more pressure is applied. The pressure drives out moisture—the molds are designed to allow water to escape—and unifies the curds into a single solid body.

Ripening

A newborn cheese is usually salty yet bland in flavor and, for harder varieties, rubbery in texture. These qualities are sometimes enjoyed—cheese curds are eaten on their own—but normally cheeses are left to rest under controlled conditions. This aging period (also called ripening, or, from the French, affinage) lasts from a few days to several years. As a cheese ages, microbes and enzymes transform texture and intensify flavor. This transformation is largely a result of the breakdown of casein proteins and milkfat into a complex mix of amino acids, amines, and fatty acids.[23]

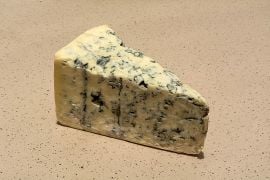

Some cheeses have additional bacteria or molds intentionally introduced before or during aging. In traditional cheesemaking, these microbes might be already present in the aging room; they are allowed to settle and grow on the stored cheeses. More often today, prepared cultures are used, giving more consistent results and putting fewer constraints on the environment where the cheese ages. These cheeses include soft ripened cheeses such as Brie and Camembert, blue cheeses such as Roquefort, Stilton, Gorgonzola, and rind-washed cheeses such as Limburger.[13]

Types

There are many types of cheese, with around 500 different varieties recognized by the International Dairy Federation,[23] more than 400 identified by Walter and Hargrove, more than 500 by Burkhalter, with some sources suggesting that there are as many as 2,000 types worldwide.[24]

Several countries claim hundreds of different types of cheese. For example, a French proverb holds there is a different French cheese for every day of the year, and Charles de Gaulle once commented "how can you govern a country in which there are 246 kinds of cheese?"). Both numbers are low estimates: France boasts over 1200 types of cheese.[25] Also, Britain has over 750 distinct local cheeses;[26] and Italy has perhaps 600.[27]

The varieties may be grouped or classified into types according to criteria such as length of ageing, texture, methods of making, fat content, animal milk, country or region of origin, etc.—with these criteria either being used singly or in combination, but with no single method being universally used.[28]

The method most commonly and traditionally used is based on moisture content, which is then further discriminated by fat content and curing or ripening methods.[23] Some attempts have been made to rationalize the classification of cheese—a scheme was proposed by Pieter Walstra which uses the primary and secondary starter combined with moisture content, and Walter and Hargrove suggested classifying by production methods which produces 18 types, which are then further grouped by moisture content.[23]

Cooking and serving

At refrigerator temperatures, the fat in a piece of cheese is as hard as unsoftened butter, and its protein structure is stiff as well. Flavor and odor compounds are less easily liberated when cold. For improvements in flavor and texture, it is widely advised that cheeses be allowed to warm up to room temperature before eating. If the cheese is further warmed, to 26–32°C (79–90°F), the fats will begin to "sweat out" as they go beyond soft to fully liquid.[20]

Cheeseboard

A cheeseboard (or cheese course) may be served at the end of a meal before or following dessert, or replacing the last course. In France, cheese is consumed before dessert, with robust red wine. The British tradition is to have cheese after dessert, accompanied by sweet wines like Port.

A cheeseboard typically has contrasting cheeses with accompaniments, such as crackers, biscuits, grapes, nuts, celery, or chutney. It may contain four to six cheeses, for example: Mature Cheddar or Comté (hard: cow's milk cheeses); Brie or Camembert (soft: cow's milk); a blue cheese such as Stilton (hard: cow's milk), Roquefort (medium: ewe's milk) or Bleu d'Auvergne (medium-soft cow's milk); a soft/medium-soft goat's cheese (e.g. Sainte-Maure de Touraine, Pantysgawn, Crottin de Chavignol).[29]

Melted cheese

Above room temperatures, most hard cheeses melt. Rennet-curdled cheeses have a gel-like protein matrix that is broken down by heat. When enough protein bonds are broken, the cheese itself turns from a solid to a viscous liquid. Soft, high-moisture cheeses will melt at around 55 °C (131 °F), while hard, low-moisture cheeses such as Parmesan remain solid until they reach about 82 °C (180 °F).[20] Acid-set cheeses, including halloumi, paneer, some whey cheeses and many varieties of fresh goat cheese, have a protein structure that remains intact at high temperatures. When cooked, these cheeses just get firmer as water evaporates.

Some cheeses, like raclette, melt smoothly; many tend to become stringy or suffer from a separation of their fats. Many of these can be coaxed into melting smoothly in the presence of acids or starch. Fondue, with wine providing the acidity, is a good example of a smoothly melted cheese dish.[20] Elastic stringiness is a quality that is sometimes enjoyed, in dishes including pizza and Welsh rarebit. Even a melted cheese eventually turns solid again, after enough moisture is cooked off. The saying "you can't melt cheese twice" (meaning "some things can only be done once") refers to the fact that oils leach out during the first melting and are gone, leaving the non-meltable solids behind.

As its temperature continues to rise, cheese will brown and eventually burn. Browned, partially burned cheese has a particular distinct flavor of its own and is frequently used in cooking, often by sprinkling atop items before baking them.

Nutrition and health

Cheese is a nutrient-dense dairy food, providing fat, protein, calcium, and phosphorus, and vitamins B12 and A. It may be better tolerated than milk for those with lactose intolerance, because cheese contains lower amounts of lactose. However, the nutritional value of cheese varies widely: One ounce of hard cheese contains 8 grams (g) of protein, 6g of saturated fat, and 180 milligrams (mg) of calcium. A half-cup of soft cheese like 4% full-fat cottage cheese has about 120 calories, 14g protein, 3g saturated fat, and 80 mg of calcium.[30]

There is ongoing debate about the impact of cheese on health. The U.S. Dietary Guidelines recommend choosing low-fat dairy (milk, yogurt, and cheese) to prevent cardiovascular disease (CVD), while other reports suggest that full-fat dairy may lower risk of CVD and type 2 diabetes. It has also been reported that cheese might be beneficial in reducing weight and the risk of stroke, specifically when replacing red meat in the diet. However, the overall dietary pattern must be considered in assessing the positive effects of cheese consumption.[30]

Effect on sleep

Scientists have debated how cheese might affect sleep. An antithetical folk belief that cheese eaten close to bedtime can cause nightmares may have arisen from the Charles Dickens novella A Christmas Carol, in which Ebenezer Scrooge attributes his visions of Jacob Marley to the cheese he ate. This belief can also be found in folklore that predates this story.[31]

The theory has been disproven multiple times. Night cheese may cause vivid dreams or otherwise disrupt sleep due to its high saturated fat content, according to studies by the British Cheese Board. Other studies indicate it may actually make people dream less.[32]

Cultural attitudes

Although cheese is a vital source of nutrition in many regions of the world and it is extensively consumed in others, its use is not universal.

Cheese is rarely found in Southeast and East Asian cuisines, presumably because dairy farming has historically been rare in these regions. Vegans and other dairy-avoiding vegetarians do not eat conventional cheese, but some vegetable-based cheese substitutes (soy or almond) are used as substitutes.[33]

Strict followers of the dietary laws of Islam and Judaism must avoid cheeses made with rennet from animals not slaughtered in a manner adhering to halal or kosher laws. Both faiths allow cheese made with vegetable-based rennet or with rennet made from animals that were processed in a halal or kosher manner. As cheese is a dairy food, under kosher rules it cannot be eaten in the same meal with any meat.

Even in cultures with long cheese traditions, consumers may perceive some cheeses that are especially pungent-smelling, or mold-bearing varieties such as Limburger or Roquefort, as unpalatable. Such cheeses are an acquired taste because they are processed using molds or microbiological cultures, allowing odor and flavor molecules to resemble those in rotten foods:

An aversion to the odor of decay has the obvious biological value of steering us away from possible food poisoning, so it is no wonder that an animal food that gives off whiffs of shoes and soil and the stable takes some getting used to.[20]

Figurative expressions

The word "cheese" has been used for numerous figurative expressions, both as a noun and as a verb. For example, in the nineteenth century, "cheese" was used as a figurative way of saying "the proper thing." The expression "big cheese" was attested in use in 1914 to mean an "important person." The expression "to cut a big cheese" was used to mean "to look important"; this figurative expression referred to the huge wheels of cheese displayed by cheese retailers as a publicity stunt. The expression "say 'cheese'" in a photograph-taking context (when the photographer wants the people to smile for the photo), which means "smile," dates from 1930 (the word was probably chosen because the "ee" encourages people to make a smile).[2]

Other figurative meanings involve the word "cheese" used as a verb. To "cheese" is recorded as meaning to "stop (what one is doing), run off." To be "cheesed off" means to be annoyed. [2]

In video game slang "to cheese it" means to win a game by using a strategy that requires minimal skill and knowledge or that exploits a glitch or flaw in game design.[34]

The adjective "cheesy" has two meanings. The first is literal, and means "cheese-like"; this definition is attested to from the late fourteenth century (e.g., "a cheesy substance oozed from the broken jar").[2] Figuratively, "cheesy" can mean "of bad quality or in bad taste" or insincere.[35]

Gallery of cheeses

Notes

- ↑ D.P. Simpson, Cassell's Latin Dictionary (Collins Reference, 1977, ISBN 978-0025225800).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 cheese Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved November 20, 2023.

- ↑ fromage Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved November 20, 2023.

- ↑ Nidhi Subbaraman, Art of cheese-making is 7,500 years old Nature News (December 12, 2012). Retrieved November 21, 2023.

- ↑ Evidence of 7,200-year-old cheese making found on the Dalmatian Coast Phys.org (September 5, 2018). Retrieved November 21, 2023.

- ↑ Maguelonne Toussaint-Samat, A History of Food (Wiley-Blackwell, 1994, ISBN 978-0631194972).

- ↑ Ancient Egypt: Cheese discovered in 3,200-year-old tomb BBC News (August 20, 2018). Retrieved November 21, 2023.

- ↑ Traci Watson, Great Gouda! World's oldest cheese found - on mummies USA Today (February 25, 2014). Retrieved November 21, 2023.

- ↑ Jenny Ridgwell and Judy Ridgway, Food around the World (Oxford University Press, 1987, ISBN 978-0198327288).

- ↑ Homer, Odyssey Book 9, 193-230 English Translation by A.T. Murray, 1919. Retrieved November 21, 2023.

- ↑ Homer, Odyssey Book 9, 231-280 English Translation by A.T. Murray, 1919. Retrieved November 21, 2023.

- ↑ T.A. Layton, The Cheese Handbook: Over 250 Varieties Described, with Recipes (Dover Publications, 2015, ISBN 978-0486229553).

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Photis Papademas and Thomas Bintsis (eds.), Global Cheesemaking Technology: Cheese Quality and Characteristics (Wiley, 2017, ISBN 978-1119046158).

- ↑ Pliny the Elder, Chapter 97 (42.)—Various kinds of cheese The Natural History translated by John Bostock, 1855. Retrieved November 21, 2023.

- ↑ David Jacoby, Byzantium, Latin Romania and the Mediterranean (Routledge, 2001, ISBN 978-0860788447).

- ↑ John Smith, Cheesemaking in Scotland – A History (Scottish Dairy Association, 1995, ISBN 978-0952532309).

- ↑ Jesse Williams and the First Cheese Factory Museum Association of New York. Retrieved November 21, 2023.

- ↑ Charles Thom and Walter Warner Fisk, The Book of Cheese (Applewood Books, 2007 (original 1918), ISBN 978-1429010740).

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Kate Arding and Elaine Khosrova, Rennet's Role Culture (December 2, 2011). Retrieved November 21, 2023.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 20.5 Harold McGee, On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen (Scribner, 2004, ISBN 978-0684800011).

- ↑ M.E. Johnson, A 100-Year Review: Cheese production and quality Journal of Dairy Science 100(12) (2017): 9952-9965. Retrieved November 21, 2023.

- ↑ Why Does Swiss Cheese Have Holes? Undeniably Dairy. Retrieved November 22, 2023.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 23.4 Patrick F. Fox, Paul L. H. McSweeney, Timothy M. Cogan, and Timothy P. Guinee, Fundamentals of Cheese Science (Springer, 2000, ISBN 978-0834212602).

- ↑ How Many Types Of Cheese Are There? Dalstrong. Retrieved November 22, 2023.

- ↑ Cheeses Centre National Interprofessionnel de l'Economie Laitière (CNIEL). Retrieved November 22, 2023.

- ↑ A Guide to British Cheese Varieties Peter's Yard. Retrieved November 22, 2023.

- ↑ Italian Cheeses Italy for me. Retrieved November 22, 2023.

- ↑ Barbara Ensrud, The Pocket Guide to Cheese (Lansdowne Press, 1981, ISBN 978-0701814830).

- ↑ Tony Naylor, How to eat: cheese and biscuits The Guardian (June 27, 2012). Retrieved November 22, 2023.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 The Nutrition Source: Cheese Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. Retrieved November 22, 2023.

- ↑ Caroline Oates, Cheese Gives You Nightmares: Old Hags and Heartburn Folklore 114(2) (2003): 205–225.

- ↑ Michael Mosley, Fast Asleep: Improve Brain Function, Lose Weight, Boost Your Mood, Reduce Stress, and Become a Better Sleeper (Atria Books, 2020, ISBN 978-1982106928).

- ↑ James D. Mauseth, Plants and People (Jones & Bartlett Learning, 2012, ISBN 978-0763785505).

- ↑ cheesed, cheesing Dictionary.com. Retrieved November 22, 2023.

- ↑ cheesy Cambridge Dictionary. Retrieved November 22, 2023.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ensrud, Barbara. The Pocket Guide to Cheese. Lansdowne Press, 1981. ISBN 978-0701814830

- Fox, Patrick F., Paul L. H. McSweeney, Timothy M. Cogan, and Timothy P. Guinee. Fundamentals of Cheese Science. Springer, 2000. ISBN 978-0834212602

- Jacoby, David. Byzantium, Latin Romania and the Mediterranean. Routledge, 2001. ISBN 978-0860788447

- Layton, T.A. The Cheese Handbook: Over 250 Varieties Described, with Recipes. Dover Publications, 2015. ISBN 978-0486229553

- Mauseth, James D. Plants and People. Jones & Bartlett Learning, 2012. ISBN 978-0763785505

- McGee, Harold. On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen. Scribner, 2004. ISBN 978-0684800011

- Mosley, Michael. Fast Asleep: Improve Brain Function, Lose Weight, Boost Your Mood, Reduce Stress, and Become a Better Sleeper. Atria Books, 2020. ISBN 978-1982106928

- Papademas, Photis, and Thomas Bintsis (eds.). Global Cheesemaking Technology: Cheese Quality and Characteristics. Wiley, 2017. ISBN 978-1119046158

- Ridgwell, Jenny, and Judy Ridgway. Food around the World. Oxford University Press, 1987. ISBN 978-0198327288

- Simpson, D.P. Cassell's Latin Dictionary. Collins Reference, 1977. ISBN 978-0025225800

- Smith, John. Cheesemaking in Scotland – A History. Scottish Dairy Association, 1995. ISBN 978-0952532309

- Thom, Charles, and Walter Warner Fisk. The Book of Cheese. Applewood Books, 2007 (original 1918). ISBN 978-1429010740

- Toussaint-Samat, Maguelonne. A History of Food. Wiley-Blackwell, 1994. ISBN 978-0631194972

External links

All links retrieved November 22, 2023.

- Is cheese good or bad for you? Medical News Today

- What Are The Different Types Of Cheese? Undeniably Dairy

- American Cheese Society

- A History of British Cheese The Courtyard Dairy

- European and French Cheese Fromage From Europe

- History of Cheese National Historic Cheesemaking Center

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.