Bauhaus

Bauhaus is the common term for the Staaatliches Bauhaus, an art and architecture school in Germany that operated from 1919 to 1933, and for its approach to design that it publicized and taught. The most natural meaning for its name (related to the German verb for "build") is Architecture House. Bauhaus was associated with the trend toward less ornate art and architecture and greater utility. The inspiration for this concern was the rise of the working class and the desire to meet the needs of masses rather than a small number of wealthy patrons. Bauhaus style became one of the most influential currents in Modernist architecture, and one of the most important currents of the New Objectivity.[1]

The Bauhaus art school had a profound influence upon subsequent developments in architecture and interior design. It existed in three German cities (Weimar from 1919 to 1925, Dessau from 1925 to 1932, Berlin from 1932 to 1933), under three different architect-directors (Walter Gropius from 1919 to 1927, Hannes Meyer from 1928 to 1930, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe from 1930 to 1933). The changes of venue and leadership resulted in a constant shifting of focus, technique, instructors, and politics. When the school moved from Weimar to Dessau, for instance, although it had been an important revenue source, the pottery shop was discontinued. When Mies took over the school in 1930, he transformed it into a private school, and would not allow any supporters of Hannes Meyer to attend it.

László Moholy-Nagy revived the school for a single year in Chicago as the New Bauhaus in 1937, before its transformation to the Institute of Design.

Context

The foundation of the Bauhaus occurred at a time of crisis and turmoil in Europe as a whole and particularly in Germany. Its establishment resulted from a confluence of a diverse set of political, social, educational and artistic development in the first two decades of the twentieth century.

Political context

The conservative modernization of the German Empire during the 1870s had maintained power in the hands of the aristocracy. It also necessitated militarism and imperialism to maintain stability and economic growth. By 1912 the rise of the leftist SPD had galvanized political positions with notions of international solidarity and socialism set against imperialist nationalism. World War I ensued from 1914‚Äď1918, resulting in the collapse of the old regime and a period of political and social uncertainty.

In 1917 in the midst of the carnage of the World War I, workers‚Äô and soldiers‚Äô collectives (Soviets) seized power in Russia. Inspired by the Russian workers‚Äô and soldiers‚Äô Soviets, similar German communist factions‚ÄĒmost notably The Spartacist League‚ÄĒwere formed, who sought a similar revolution for Germany. The following year, the death throes of the war provoked the German Revolution, with the SPD securing the abdication of the Kaiser and the formation of a revolutionary government. On January 1, 1919, the Spartacist League attempted to take control of Berlin, an action that was brutally suppressed by the combined forces of the SPD, the remnants of the German Army, and right-wing paramilitary groups.

Elections were held on the January 19, and the Weimar Republic was established. Still, Communist revolution was still the goal for some, and a Soviet-style republic was declared in Munich, before its suppression by the right wing Freikorps and regular army. Sporadic fighting continued to flare up around the country.

Bauhaus and German modernism

The design innovations commonly associated with Gropius and the Bauhaus‚ÄĒthe radically simplified forms, the rationality and functionality, and the idea that mass-production was reconcilable with the individual artistic spirit‚ÄĒwere already partly developed in Germany before the Bauhaus was founded.

The German national designers' organization Deutscher Werkbund was formed in 1907 by Hermann Muthesius to harness the new potentials of mass production, with a mind towards preserving Germany's economic competitiveness with England. In its first seven years, the Werkbund came be to regarded as the authoritative body on questions of design in Germany, and was copied in other countries. Many fundamental questions of craftsmanship vs. mass production, the relationship of usefulness and beauty, the practical purpose of formal beauty in a commonplace object, and whether or not a single proper form could exist, were argued out among its 1870 members (by 1914).

Beginning in June 1907, Peter Behrens' pioneering industrial design work for the German electrical company AEG successfully integrated art and mass production on a large scale. He designed consumer products, standardized parts, created clean-lined designs for the company's graphics, developed a consistent corporate identity, built the modernist landmark AEG Turbine Factory, and made full use of newly developed materials such as poured concrete and exposed steel. Behrens was a founding member of the Werkbund, and both Walter Gropius and Adolf Meier worked for him in this period.

The Bauhaus was founded in 1919, the same year as the Weimar Constitution, and at a time when the German Zeitgeist turned from emotional Expressionism to the matter-of-fact New Objectivity. An entire group of working architects, including Erich Mendelsohn, Bruno Taut and Hans Poelzig, turned away from fanciful experimentation, and turned toward rational, functional, sometimes standardized building.

Beyond the Bauhaus, many other significant German-speaking architects in the 1920s responded to the same aesthetic issues and material possibilities as the school. They also responded to the promise of a 'minimal dwelling' written into the Constitution. Ernst May, Bruno Taut, and Martin Wagner, among others, built large housing blocks in Frankfurt and Berlin. The acceptance of modernist design into everyday life was the subject of publicity campaigns, well-attended public exhibitions like the Weissenhof Estate, films, and sometimes fierce public debate.

The entire movement of German architectural modernism was known as Neues Bauen.

History of the Bauhaus

| Bauhaus and its Sites in Weimar and Dessau* | |

|---|---|

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

| |

| State Party | |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | ii, iv, vi |

| Reference | 729 |

| Region** | Europe and North America |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 1996  (20th Session) |

| * Name as inscribed on World Heritage List. ** Region as classified by UNESCO. | |

Weimar

The school was founded by Walter Gropius in the conservative city of Weimar in 1919, as a merger of the Weimar School of Arts and Crafts and the Weimar Academy of Fine Arts. His opening manifesto proclaimed the desire to

- "to create a new guild of craftsmen, without the class distinctions which raise an arrogant barrier between craftsman and artist."

Most of the contents of the workshops had been sold off during World War I. The early intention was for the Bauhaus to be a combined architecture school, crafts school, and academy of the arts. Much internal and external conflict ensued.

Gropius argued that a new period of history had begun with the end of the war. He wanted to create a new architectural style to reflect this new era. His style in architecture and consumer goods was to be functional, cheap and consistent with mass production. To these ends, Gropius wanted to reunite art and craft to arrive at high-end functional products with artistic pretensions. The Bauhaus issued a magazine called "Bauhaus" and a series of books called Bauhausb√ľcher. Since the country lacked the quantity of raw materials that the United States and Great Britain had, they had to rely on the proficiency of its skilled labor force and ability to export innovative and high quality goods. Therefore, designers were needed and so was a new type of art education. The school‚Äôs philosophy basically stated that the artist should be trained to work with the industry.

Funding for the Bauhaus was initially provided by the Thuringian state parliament. The primary support came from the Social Democratic party. In February 1924, the Social Democrats lost control of the state parliament to the nationalists, who were unsympathetic to the Bauhaus' leftist political leanings. The Ministry of Education placed the staff on six-month contracts and cut the school's funding in half. Gropius had already been looking for alternative sources of funding, so this loss of support proved insurmountable. Together with the Council of Masters he announced the closure of the Bauhaus from the end of March 1925. The school moved to Dessau the next year.

After the Bauhaus moved to Dessau, a school of industrial design with teachers and staff less antagonistic to the conservative political regime remained in Weimar. This school was eventually known as the Technical University of Architecture and Civil Engineering, and in 1996 changed its name to Bauhaus University Weimar.

Dessau

The Dessau years saw a remarkable change in direction for the school. According to Elaine Hoffman, Gropius had approached the Dutch architect Mart Stam to run the newly-founded architecture program, and when Stam declined the position, Gropius turned to Stam's friend and colleague in the ABC group, Hannes Meyer. Gropius would come to regret this decision.

The charismatic Meyer rose to director when Gropius resigned in February 1928, and Meyer brought the Bauhaus its two most significant building commissions for the school, both of which still exist: five apartment buildings in the city of Dessau, and the headquarters of the Federal School of the German Trade Unions (ADGB) in Bernau. Meyer favored measurements and calculations in his presentations to clients, along with the use of off-the-shelf architectural components to reduce costs; this approach proved attractive to potential clients. The school turned its first profit under his leadership in 1929.

But Meyer also generated a great deal of conflict. As a radical functionalist, he had no patience with the aesthetic program, and forced the resignations of Herbert Bayer, Marcel Breuer, and other longtime instructors. As a vocal Communist, he encouraged the formation of a Communist student organization. In the increasingly dangerous political atmosphere in the Weimar era, this became a threat to the existence of the school, and to the personal safety of anyone involved. Meyer was also compromised by a sexual scandal involving one of his students, and Gropius fired him in 1930.

Berlin

Although neither the Nazi Party nor Hitler himself had a cohesive architectural 'policy' in the 1930s, Nazi writers like Wilhelm Frick and Alfred Rosenberg had labeled the Bauhaus "un-German," criticizing its modernist styles, deliberately generating public controversy over issues like flat roofs. Increasingly through the early 1930s, they characterized the Bauhaus as a front for Communists, Russian, and social liberals. This characterization was helped by the actions of its second director, Hannes Meyer, who with a number of loyal students moved to the Soviet Union in 1930.

Under political pressure the Bauhaus was closed on the orders of the Nazi regime on April 11, 1933. The closure, and the response of Mies van der Rohe, is fully documented in Elaine Hoffman's Architects of Fortune.

Architectural output

The paradox of the early Bauhaus was that, although its manifesto proclaimed that the ultimate aim of all creative activity was building, the school wouldn't offer classes in architecture until 1927. The single most profitable tangible product of the Bauhaus was its wallpaper.

During the years under Gropius (1919‚Äď1927), he and his partner Adolf Meyer observed no real distinction between the output of his architectural office and the school. So the built output of Bauhaus architecture in these years is the output of Gropius: the Sommerfeld house in Berlin, the Otte house in Berlin, the Auerbach house in Jena, and the competition design for the Chicago Tribune Tower, which brought the school much attention. The definitive 1926 Bauhaus building in Dessau is also attributed to Gropius. Apart from contributions to the 1923 Haus am Horn, student architectural work amounted to unbuilt projects, interior finishes, and craft work like cabinets, chairs and pottery.

In the next two years under the outspoken Swiss Communist architect Hannes Meyer, the architectural focus shifted away from aesthetics and towards functionality. But there were major commissions: one by the city of Dessau for five tightly designed "Laubenganghäuser" (apartment buildings with balcony access), which are still in use today, and another for the headquarters of the Federal School of the German Trade Unions (ADGB) in Bernau bei Berlin. Meyer's approach was to research users' needs and scientifically develop the design solution.

Mies van der Rohe repudiated Meyer's politics, his supporters, and his architectural approach. As opposed to Gropius' "study of essentials," and Meyer's research into user requirements, Mies advocated a "spatial implementation of intellectual decisions," which effectively meant an adoption of his own aesthetics. Neither Mies nor his Bauhaus students saw any projects built during the 1930s.

The popular conception of the Bauhaus as the source of extensive Weimar-era working housing is largely apochryphal. Two projects, the apartment building project in Dessau and the Törten row housing also in Dessau fall in that category, but developing worker housing was not the top priority for Gropius or Mies. It was the Bauhaus contemporaries Bruno Taut, Hans Poelzig and particularly Ernst May, as the city architects of Berlin, Dresden and Frankfurt respectively, who are rightfully credited with the thousands of housing units built in Weimar Germany. In Taut's case, the housing may still be seen in SW Berlin, is still occupied, and can be reached by going easily from the Metro Stop Onkel Tom's Hutte.

Impact

The Bauhaus had a major impact on art and architectural trends in Western Europe, the United States and Israel (particularly in White City, Tel Aviv) in the decades following its demise, as many of the artists involved either fled or were exiled by the Nazi regime.

Gropius, Breuer, and Moholy-Nagy re-assembled in England during the mid-1930s to live and work in the Isokon project before the war caught up to them. Both Gropius and Breuer went on to teach at the Harvard Graduate School of Design and worked together before their professional split in 1941. The Harvard School was enormously influential in America in the late 1940s and early 1950s, producing such students as Philip Johnson, I.M. Pei, Lawrence Halprin and Paul Rudolph, among many others.

In the late 1930s, Mies van der Rohe re-settled in Chicago, enjoyed the sponsorship of the influential Philip Johnson, and became one of the pre-eminent architects in the world. Moholy-Nagy also went to Chicago and founded the New Bauhaus school under the sponsorship of industrialist and philanthropist Walter Paepcke. Printmaker and painter Werner Drewes was also largely responsible for bringing the Bauhaus aesthetic to America and taught at both Columbia University and Washington University in St. Louis. Herbert Bayer, sponsored by Paepcke, moved to Aspen, Colorado in support of Paepcke's Aspen projects.

One of the main objectives of the Bauhaus was to unify art, craft, and technology. The machine was considered a positive element, with industrial and product design as important components. Vorkurs ("initial" or "preliminary course") was taught; this is the modern day Basic Design course that has become one of the key foundational courses offered in architectural and design schools across the globe. There was no teaching of history in the school because everything was supposed to be designed and created according to first principles rather than by following precedent.

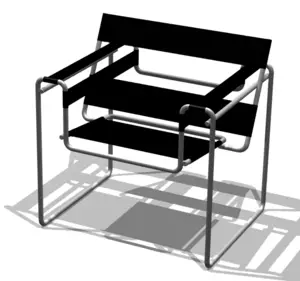

One of the most important contributions of the Bauhaus is in the field of modern furniture design. The world famous and ubiquitous Cantilever chair by Dutch designer Mart Stam, using the tensile properties of steel, and the Wassily Chair designed by Marcel Breuer are but two examples.

The physical plant at Dessau survived World War II and was operated as a design school with some architectural facilities by the Communist German Democratic Republic. This included live stage productions in the Bauhaus theater under the name of Bauhausb√ľhne ("Bauhaus Stage"). After German reunification, a reorganized school continued in the same building, with no essential continuity with the Bauhaus under Gropius in the early 1920s [1].

In 1999 Bauhaus-Dessau College started to organize postgraduate programs with participants from all over the world. This effort has been supported by the Bauhaus-Dessau Foundation which was founded in 1994 as a public institution.

American art schools have also rediscovered the Bauhaus school. The Master Craftsman Program at Florida State University bases its artistic philosophy on Bauhaus theory and practice.

Many outstanding artists of their time were lecturers at Bauhaus:

|

|

Gallery

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ James Stevens Curl. A Dictionary of Architecture and Landscape Architecture, second ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006. ISBN 0198606788)

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bax, Marty. Bauhaus Lecture Notes 1930‚Äď1933. Theory and practice of architectural training at the Bauhaus, based on the lecture notes made by the Dutch ex-Bauhaus student and architect J.J. van der Linden of the Mies van der Rohe curriculum. Amsterdam, Architectura & Natura 1991. ISBN 9071570045

- Droste, Magdalena, Peter Gossel, Editors. Bauhaus. Taschen America LLC, 2005. ISBN 3822836494

- Hoffman, Elaine, Architects of Fortune.

- Schlemmer, Oskar and Tut Schlemmer, (Ed.) The Letters and Diaries of Oskar Schlemmer, Translated by Krishna Winston. Wesleyan University Press, 1972. ISBN 0819540471

External links

All links retrieved September 26, 2023.

- Bauhaus-Archiv in Berlin

- Bauhaus Dessau Foundation

- Bauhaus School

- Bauhaus in America. A documentary describing the impact on Bauhaus on American architecture.

- Memories of one of the few English-speaking Bauhaus students

| Western art movements |

| Renaissance · Mannerism · Baroque · Rococo · Neoclassicism · Romanticism · Realism · Pre-Raphaelite · Academic · Impressionism · Post-Impressionism |

| 20th century |

| Modernism ¬∑ Cubism ¬∑ Expressionism ¬∑ Abstract expressionism ¬∑ Abstract ¬∑ Neue K√ľnstlervereinigung M√ľnchen ¬∑ Der Blaue Reiter ¬∑ Die Br√ľcke ¬∑ Dada ¬∑ Fauvism ¬∑ Art Nouveau ¬∑ Bauhaus ¬∑ De Stijl ¬∑ Art Deco ¬∑ Pop art ¬∑ Futurism ¬∑ Suprematism ¬∑ Surrealism ¬∑ Minimalism ¬∑ Post-Modernism ¬∑ Conceptual art |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.