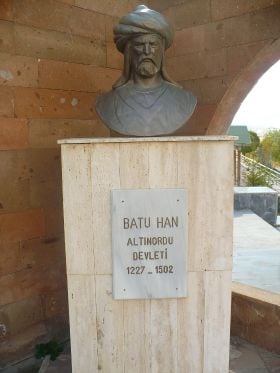

Batu Khan

Batu Khan (c. 1205 ‚Äď 1255) was a Mongol ruler and the founder of the Blue Horde. Batu was a son of Jochi and grandson of Genghis Khan. His Blue Horde became the Golden Horde (or Kipchak Khanate), which ruled Rus and the Caucasus for around 250 years, after also destroying the armies of Poland and Hungary. He was the nominal leader of the Mongol invasion of Europe, although his general, Subutai is credited with masterminding strategy. After gaining control of Rus, Volga Bulgaria and the Crimea he invaded Europe winning the Battle of Mohi against B√©la IV of Hungary on April 11, 1241. In 1246, he returned to Mongolia for the election of the new Great Khan, perhaps hoping to be a candidate. When his rival, Guyuk Khan became Great Khan, he returned to his khanate and built his capital at Sarai on the Volga. Known as Saria Batu, this remained the capital of the Golden Horde until it collapsed.

Batu's Khan's role in the Russian and European campaigns is sometimes downplayed due to the role played by his general. However, it is to Batu Khan's credit that he listened to his general's counsel, putting his long experience in the field to good use. Perhaps the most significant aspect of Batu Khan's legacy and of the Mongol invasion of Europe was that it helped to draw Europe's attention to the world beyond the European space. As long as the Mongol Empire itself lasted, the Silk Road was protected and secure, open for travel by diplomats such as the Papal Nuncio who attended the 1246 Assembly as well as for trade. To some extent, the Mongol Empire and the Mongol invasion of Europe, of which Batu Khan was at least nominally in charge, served as a bridge between different cultural worlds.

Bloodline of the Kipchak Khans

Although Genghis Khan recognized Jochi as his son, his parentage was always in question, as his mother B√∂rte, Genghis Khan's wife, had been captured and he was born shortly after her return. During the lifetime of Genghis, this issue was public knowledge, but it was taboo to publicly discuss it. Still, it drove a wedge between Jochi and his father; just before Jochi's death, he and Genghis almost fought a civil war because of Jochi's sullen refusal to join in military campaigns. Jochi also was given only 4,000 Mongol soldiers to carve out his own Khanate. Jochi's son Batu, described as "Jochi's second and most able son,"[1] gained most of his soldiers by recruiting amongst the Turkic people he defeated, mostly Kipchak Turks. Batu was later instrumental in setting the house of his uncle √Ėgedei aside in favor of the house of Tolui, his other uncle.

After Jochi and Genghis died, Jochi's lands were divided between Batu and his older brother Orda. Orda's White Horde ruled the lands roughly between the Volga river and Lake Balkhash, while Batu's Golden Horde ruled the lands west of the Volga.

Following the death of Batu's heir, Sartak, Batu's brother Berke inherited the Golden Horde. Berke was not inclined to unite with his cousins in the Mongol family, making war on Hulagu Khan, though he officially recognized the Khanate of China as his overlord‚ÄĒin theory only. In fact, Berke was an independent ruler by then. Fortunately for Europe, Berke did not share Batu's interest in conquering it, however, he demanded Hungarian King Bela IV's submission and sent his general Borolday to Lithuania and Poland.

Batu had at least four children:

- Sartaq, khan of the Golden Horde from 1255‚Äď1256

- Toqoqan[2]

- Andewan

- Ulagchi (probably the son of Sartaq)

Batu's mother Ukhaa ujin belonged to the Mongol Onggirat clan while his chief khatun Borakchin was Alchi-Tatar.

Early years

After his Jochi's death, his territory was divided between his sons; Orda received "the right bank of the Syr Darya and the districts around the Sari Bu" and Batu the "north coast of the Caspian Sea as far as the Ural River."[1]

In 1229, Ogedei dispatched three tumens under Kukhdei and Sundei against the tribes on lower Ural. Batu then joined Ogedei's military campaign in Jin Dynasty in North China while they were fighting Bashkirs, Cumans, Bulghars, and Alans. Despite heavy resistance by their foes, the Mongols conquered many cities of the Jurchens and made the Bashkirs their allies.

Invasion of Rus

In 1235 Batu, who had earlier directed the conquest of the Crimea, was assigned an army of possibly 130,000 to oversee an invasion of Europe. His relatives and cousins Guyuk, Buri, Mongke, Khulgen, Kadan, Baidar, and notable Mongol generals Subotai (–°“Į–Ī—ć—ć–ī—ć–Ļ), Borolday (–Ď–ĺ—Ä–ĺ–Ľ–ī–į–Ļ) and Mengguser (–ú”©–Ĺ—Ö—Ā–į—Ä) joined him by order of his uncle Ogedei. The army, actually commanded by Subutai, crossed the Volga and invaded Volga Bulgaria in 1236. It took them a year to crush the resistance of the Volga Bulgarians, Kypchaks, and Alani.

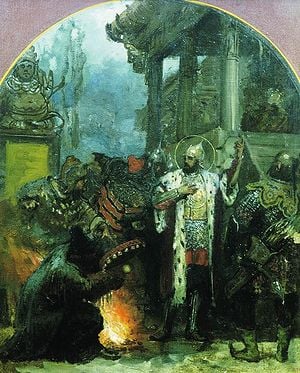

In November 1237, Batu Khan sent his envoys to the court of Yuri II of Vladimir and demanded his allegiance. A month later, the hordes besieged Ryazan. After six days of bloody battle, the city was totally annihilated. Alarmed by the news, Yuri II sent his sons to detain the horde but were soundly defeated. Having burnt Kolomna and Moscow, the horde laid siege to Vladimir on February 4, 1238. Three days later the capital of Vladimir-Suzdal was taken and burnt to the ground. The royal family perished in the fire, while the grand prince hastily retreated northward. Crossing the Volga, he mustered a new army, which was totally exterminated by the Mongols on the Sit' River on March 4.

Thereupon Batu Khan divided his army into smaller units, which ransacked fourteen Rus' cities: Rostov, Uglich, Yaroslavl, Kostroma, Kashin, Ksnyatin, Gorodets, Galich, Pereslavl-Zalessky, Yuriev-Polsky, Dmitrov, Volokolamsk, Tver, and Torzhok. The most difficult to take was the small town of Kozelsk, whose boy-prince Titus and inhabitants resisted the Mongols for seven weeks. The only major cities to escape destruction wereSmolensk, who submitted to the Mongols and agreed to pay tribute, and Novgorod with Pskov, which could not be reached by the Mongols on account of considerable distance and winter weather.

In the summer of 1238, Batu Khan devastated the Crimea and subdued Mordovia. In the winter of 1239, he sacked Chernigov and Pereyaslav. After several months of siege, the horde stormed Kyiv in December 1239. Despite fierce resistance by Danylo of Halych, Batu Khan managed to take two principal capitals of his land, Halych and Volodymyr-Volyns'kyi. The Rus' states were left as vassals rather than integrated into the central Asian empire.

Invasion of Central Europe

Batu Khan decided to push into central Europe. Some modern historians speculate that Batu Khan intended primarily to assure his flanks were safe for the future from possible interference from the Europeans, and partially as a precursor to further conquest. Most believe he intended the conquest of all Europe, as soon as his flanks were safe, and his forces ready. He may have had Hungary in sight because Russian princes and other people had taken refuge there and might present a future threat.

The Mongols invaded central Europe in three groups. One group conquered Poland, defeating a combined force under Henry the Pious, Duke of Silesia and the Grand Master of the Teutonic Order at Legnica. A second crossed the Carpathians and a third followed the Danube. The armies re-grouped and crushed Hungary in 1241, defeating the army led by Béla IV of Hungary at the Battle of Mohi on April 11. The armies swept the plains of Hungary over the summer and in the spring of 1242, they extended their control into Austria and Dalmatia as well as invading Bohemia.

This attack on Europe was planned and carried out by Subutai, under the nominal command of Batu. During his campaign in Central Europe, Batu wrote to Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor demanding his surrender. The latter replied that he knew bird-hunting well and would wish to be Batu's eagle keeper should he ever lose his throne.[3] The Emperor and Pope Gregory IX called a crusade against the Mongol Empire. Subutai achieved perhaps his most lasting fame with his victories in Europe and in Eastern Persia. Having devastated the various Rus principalities, he sent spies into Poland, Hungary, and as far as Austria, in preparation for an attack into the heartland of Europe. Having formed a clear picture of the European kingdoms, he prepared an attack with two other princes of the blood, Kaidu and Kadan, although the actual commander in the field was once again General Subutai. While Kaidu's northern force won the Battle of Legnica and Kadan's army triumphed in Transylvania, Subutai was waiting for them on the Hungarian plain. The newly reunited army then withdrew to the Sajo river where they inflicted defeat on King Béla IV at the Battle of Mohi.

Aftermath

By late 1241, Batu and Subutai were finishing plans to invade Austria, Italy and Germany, when the news came of the death of √Ėgedei Khan (died in December, 1241), and the Mongols withdrew in the late spring of 1242, as the Princes of the blood, and Subutai, were recalled to Karakorum where the kurultai (meeting or assembly) was held. Batu did not actually attend the assembly; he learned that Guyuk had secured enough support to win election and stayed away. Instead, he turned to consolidate his conquests in Asia and the Urals. He did not have Subutai with him when he returned to his domain‚ÄĒSubutai had remained in Mongolia, where he died in 1248‚ÄĒand Batu's animosity to Guyuk Khan made any further European invasion impossible. This animosity dated from 1240, when at a feat to celebrate the Russian victory, Batu had claimed the victor's right to drink first from the ceremonial beaker. His cousin apparently thought the right belonged to Batu's general.[4] The deterioration of relations between the grandsons of Genghis Khan ultimately brought about the end of the Mongol Empire. After his return, Batu Khan established the capital of his khanate at Sarai on the lower Volga. He was planning new campaigns after Guyuk's death, intent on carrying out Subutai's original plans to invade Europe when he died in 1255. The khanate passed to his son, Sartaq, who decided against the invasion of Europe. Hartog speculates that had the Mongols continued with their campaign, they would have reached the Atlantic since "no European army could have resisted the victorious Mongols."[5]

Legacy

The Kipchak Khanate ruled Russia through local princes for the next 230 years.

The Kipchak Khanate was known in Rus and Europe as the Golden Horde (Zolotaya Orda) some think because of the Golden color of the Khan's tent. "Horde" comes from the Mongol word "orda/ordu" or camp. "Golden" is thought to have had a similar meaning to "royal" (Royal Camp). Of all the Khanates, the Golden Horde ruled longest. Long after the fall of the Yuan Dynasty in China, and the fall of Ilkhanate in Middle East, the descendants of Batu Khan continued to rule the Russian steppes. Although Subutai is credited as the real mastermind behind the campaigns waged by Batu; "It is possible that Batu was only the supreme commander in name and that the real command lay in the hands" of Subutai but Batu was not unskilled in making "good use of the rivalries existing between the various kingdoms of Europe" to prosecute the Mongol campaign.[6] It is also to Batu Khan's credit that he listened to his general's counsel and put his long experience in the field to good use.

Perhaps the most significant aspect of Batu Khan's legacy and of the Mongol invasion of Europe was that it helped to draw Europe's attention to the world beyond the European space, especially China, which actually became more accessible for trade as long as the Mongol Empire itself lasted since the Silk Road was protected and secure. To some extent, the Mongol Empire and the Mongol invasion of Europe served as a bridge between different cultural worlds.

| Preceded by: Jochi |

Khan of Blue Horde 1240‚Äď1255 |

Succeeded by: Sartaq |

Notes

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Chambers, James. The Devil's Horsemen: The Mongol Invasion of Europe. New York, NY: Atheneum, 1979. ISBN 978-0689109423

- de Hartog, Leo. Genghis Khan: conqueror of the World. New York, NY: Barnes & Noble, 1999. ISBN 978-0760711927

- Morgan, David. The Mongols. The Peoples of Europe. Oxford, UK: B. Blackwell, 1986. ISBN 978-0631135562

- Nicolle, David, and Richard Hook. The Mongol Warlords: Genghis Khan, Kublai Khan, Hulegu, Tamerlane. London, UK: Brookhampton Press, 1998. ISBN 978-1860194078

- Saunders, J.J. The History of the Mongol Conquests. New York, NY: Barnes & Noble, 1971. ISBN 978-0389044512

- Sicker, Martin. The Islamic World in Ascendancy from the Arab Conquests to the Siege of Vienna. Westport, CT: Praeger, 2000. ISBN 978-0313001116

- Soucek, Svatopluk. A History of Inner Asia. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0521651691

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.