Difference between revisions of "Evidence of evolution" - New World Encyclopedia

Rick Swarts (talk | contribs) |

Rick Swarts (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 115: | Line 115: | ||

===Evidence from comparative anatomy=== | ===Evidence from comparative anatomy=== | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | ====Overview==== | |

| − | ===Homologous structures | + | The study of comparative anatomy also yields evidence for the theory of descent with modification. For one, there are structures in diverse species that have similar internal organization yet perform different functions. [[Vertebrate]] limbs are a common example of such ''homologous structures.'' [[Bat]] wings, for example, are very similar to human hands. Also similar are the forelimbs of the penguin, the porpoise, the rat, and the [[alligator]]. In addition, these features derive from the same structures in the [[embryo]] stage. As queried earlier, “why would a rat run, a bat fly, a porpoise swim and a man type” all with limbs using the same bone structure if not coming from a common ancestor, since these are surely not the most ideal structures for each use (Gould 1983). |

| + | |||

| + | Likewise, a structure may exist with little or no purpose in one organism, yet the same structure has a clear purpose in other species. These features are called [[vestigial organ]]s or vestigial characters. The human [[wisdom teeth]] and [[Vermiform appendix|appendix]] are common examples. Likewise, some [[snake]]s have pelvic bones and limb bones, and some blind salamanders and blind cave fish have eyes. Such features would be the prediction of the theory of descent with modification, suggesting that they share a common ancestry with organisms that have the same structure, but which is functional. | ||

| + | |||

| + | For the point of view of classification, it can be observed that various species exhibit a sense of "relatedness," such as various catlike mammals can be put in the same family (Felidae), dog-like mammals in the same family (Canidae), and bears in the same family (Ursidae), and so forth, and then these and other similar mammals can be combined into the same order (Carnivora). This sense of relatedness, from external features, fits the expectations of the theory of descent with modification. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Comparative anatomy|Comparative study of the anatomy]] of groups of [[plant]]s reveals that certain structural features are basically similar. For example, the basic structure of all [[flower]]s consists of [[sepal]]s, [[petal]]s, [[carpel|stigma, style and ovary]]; yet the size, color, number of parts, and specific structure are different for each individual species. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In a more general sense, all organisms utilize [[cell (biology)|cells]] as the basic unit of life and pass on their heredity using a nearly universal genetic code, reflecting the likelihood that common origin. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Phylogeny]], the study of the ancestry (pattern and history) of organisms, yields a phylogenetic tree to show such relatedness (or a cladogram in other taxonomic disciplines). | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Homologous structures==== | ||

If widely separated groups of organisms are originated from a common ancestry, they are expected to have certain basic features in common. The degree of [[similarity|resemblance]] between two organisms should indicate how closely related they are in evolution: | If widely separated groups of organisms are originated from a common ancestry, they are expected to have certain basic features in common. The degree of [[similarity|resemblance]] between two organisms should indicate how closely related they are in evolution: | ||

* Groups with little in common are assumed to have diverged from a [[common ancestor]] much earlier in geological history than groups which have a lot in common; | * Groups with little in common are assumed to have diverged from a [[common ancestor]] much earlier in geological history than groups which have a lot in common; | ||

| − | * In deciding how closely related two animals are, a comparative anatomist looks for [[structure]]s that are fundamentally similar, even though they may serve different functions in the [[adult]] | + | * In deciding how closely related two animals are, a comparative anatomist looks for [[structure]]s that are fundamentally similar, even though they may serve different functions in the [[adult]]. |

* In cases where the similar structures serve different functions in adults, it may be necessary to trace their origin and embryonic development. A similar developmental origin suggests they are the same structure, and thus likely to be derived from a common ancestor. | * In cases where the similar structures serve different functions in adults, it may be necessary to trace their origin and embryonic development. A similar developmental origin suggests they are the same structure, and thus likely to be derived from a common ancestor. | ||

| − | + | In biology, [[homology]] is commonly defined as any similarity between structures that is attributed to their shared ancestry. There are examples in different levels of organization. Entire anatomical structures that are similar in different biological taxa ([[species]], [[genus|genera]], etc.) would be termed homologous if they evolved from the same structure in some ancestor, and partial sequences in [[DNA]] or [[protein]] would be similarly labeled if common ancestry was the cause. | |

| + | |||

| + | This is a redefinition from the classical understanding of the term, which predates [[Charles Darwin|Darwin]]'s theory of [[evolution]], being coined by [[Richard Owen]] in the 1840s. Historically, homology was defined as similarity in structure and position, such as the pattern of [[bone]]s in a bat's wing and those in a porpoise's flipper (Wells 2000). Conversely, the term ''analogy'' signified functional similarity, such as the wings of a bird and those of a [[butterfly]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Homology in the classical sense, as similarity in structure and position of anatomical features between different organisms, was an important evidence used by Darwin. Similarity in structures between diverse organisms—such as the similar skeletal structures (utilizing same bones) of the forelimbs of [[human]]s, [[bat]]s, [[whale]]s, [[bird]]s, [[dog]]s, and [[alligator]]s—provides evidence of [[evolution#theory of descent with modification|evolution by common descent]] (theory of descent with modification). There is evidence that new forms develop on the foundation of earlier stages. | ||

| + | However, it would be incorrect to state that homology, as presently defined, provides evidence of evolution because it would be circular reasoning, with homology defined as similarity due to shared ancestry. Mayr (1982) states, "After 1859 there has been only one definition of homologous that makes biological sense... Attributes of two organisms are homologous when they are derived from an equivalent characteristics of the common ancestor." | ||

When a group of organisms share a homologous structure which is specialized to perform a variety of functions in order to adapt different environmental conditions and modes of life are called [[adaptive radiation]]. The gradual spreading of organisms with adaptive radiation is known as [[divergent evolution]]. | When a group of organisms share a homologous structure which is specialized to perform a variety of functions in order to adapt different environmental conditions and modes of life are called [[adaptive radiation]]. The gradual spreading of organisms with adaptive radiation is known as [[divergent evolution]]. | ||

| − | =====Pentadactyl limb===== | + | =====Homology: Pentadactyl limb===== |

[[Image:Evolution pl.png|thumb|right|500px|'''Figure 5a''': The principle of [[homology (biology)|homology]] illustrated by the adaptive radiation of the forelimb of mammals. All conform to the basic pentadactyl pattern but are modified for different usages. The third metacarpal is shaded throughout; the shoulder is crossed-hatched.]] | [[Image:Evolution pl.png|thumb|right|500px|'''Figure 5a''': The principle of [[homology (biology)|homology]] illustrated by the adaptive radiation of the forelimb of mammals. All conform to the basic pentadactyl pattern but are modified for different usages. The third metacarpal is shaded throughout; the shoulder is crossed-hatched.]] | ||

| − | The pattern of limb bones called [[pentadactyl limb]] is an example of homologous structures (Fig. 5a). | + | The pattern of limb bones called [[pentadactyl limb]] is an example of homologous structures (Fig. 5a). This pattern is found in all classes of [[tetrapod]]s (''i.e.'' from [[amphibian]]s to [[mammal]]s). It can even be traced back to the [[fin]]s of certain fossil fishes from which the first amphibians are thought to have evolved. The limb has a single proximal bone ([[humerus]]), two distal bones ([[radius]] and [[ulna]]), a series of [[carpal]]s ([[wrist]] bones), followed by five series of metacarpals ([[hand|palm]] bones) and [[phalange]]s (digits). Throughout the tetrapods, the fundamental structures of pentadactyl limbs are the same, indicating that they originated from a common ancestor. But it is considered that in the course of evolution, these fundamental structures have been modified. They have become superficially different and unrelated structures to serve different functions in adaptation to different environments and modes of life. This phenomenon is clearly shown in the forelimbs of mammals. For example: |

* In the [[monkey]], the forelimbs are much elongated to form a grasping hand for climbing and swinging among trees. | * In the [[monkey]], the forelimbs are much elongated to form a grasping hand for climbing and swinging among trees. | ||

* In the [[pig]], the first digit is lost, and the second and fifth digits are reduced. The remaining two digits are longer and stouter than the rest and bear a hoof for supporting the body. | * In the [[pig]], the first digit is lost, and the second and fifth digits are reduced. The remaining two digits are longer and stouter than the rest and bear a hoof for supporting the body. | ||

| Line 142: | Line 158: | ||

* In the [[bat]], the forelimbs have turned into [[wing]]s for flying by great elongation of four digits, and the [[hook]]-like first digit remains free for hanging from [[tree]]s. | * In the [[bat]], the forelimbs have turned into [[wing]]s for flying by great elongation of four digits, and the [[hook]]-like first digit remains free for hanging from [[tree]]s. | ||

| − | =====Insect mouthparts===== | + | =====Homology: Insect mouthparts===== |

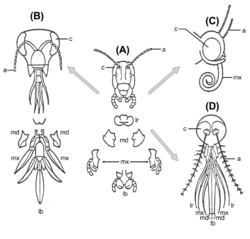

[[Image:Evolution insect mouthparts.png|thumb|left|250px|'''Figure 5b''': [[Adaptive radiation]] of insect mouthparts: a, [[antenna (biology)|antennae]]; c, [[compound eye]]; lb, labrium; lr, labrum; md, mandibles; mx, maxillae.]] | [[Image:Evolution insect mouthparts.png|thumb|left|250px|'''Figure 5b''': [[Adaptive radiation]] of insect mouthparts: a, [[antenna (biology)|antennae]]; c, [[compound eye]]; lb, labrium; lr, labrum; md, mandibles; mx, maxillae.]] | ||

| − | + | In insects,the basic structures of the mouthparts are the same, including a [[labrum]] (upper lip), a pair of [[mandible]]s, a [[hypopharynx]] (floor of mouth), a pair of [[maxillae]], and a [[labium]]. These structures are enlarged and modified; others are reduced and lost. The modifications enable the insects to exploit a variety of food materials (Fig. 5b): | |

| − | (A) Primitive state — biting and chewing: | + | (A) Primitive state — biting and chewing: e.g., [[grasshopper]]. Strong mandibles and maxillae for manipulating food. |

| − | (B) Ticking and biting: | + | (B) Ticking and biting: e.g., [[honeybee]]. Labium long to lap up [[nectar]]; mandibles chew [[pollen]] and mold [[wax]]. |

| − | (C) Sucking: | + | (C) Sucking: e.g., [[butterfly]]. Labrum reduced; mandibles lost; maxillae long forming sucking tube. |

| − | (D) Piercing and sucking, | + | (D) Piercing and sucking, e.g, [[mosquito|female mosquito]]. Labrum and maxillae form tube; mandibles form piercing stylets; labrum grooved to hold other parts. |

| − | =====Other | + | =====Homology: Other arthropod appendages ===== |

| − | Insect mouthparts and antennae are considered homologues of insect legs. Parallel developments are seen in some [[ | + | Insect mouthparts and [[antenna (anatomy)|antennae]] are considered homologues of insect legs. Parallel developments are seen in some [[arachnid]]s: The anterior pair of legs may be modified as analogues of antennae, particularly in [[whip scorpians]], which walk on six legs. These developments provide support for the theory that complex modifications often arise by duplication of components, with the duplicates modified in different directions. |

====Analogous structures and convergent evolution==== | ====Analogous structures and convergent evolution==== | ||

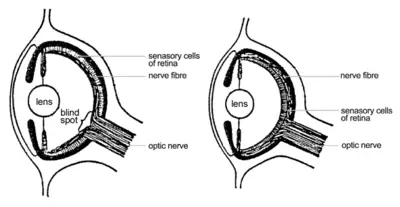

[[Image:Evolution eye.png|thumb|right|400px|'''Figure 6''': Inverted retina of vertebrate (left) and non-inverted retina of octopus (right)]] | [[Image:Evolution eye.png|thumb|right|400px|'''Figure 6''': Inverted retina of vertebrate (left) and non-inverted retina of octopus (right)]] | ||

| − | Under similar environmental conditions, fundamentally different structures in different groups of organisms may undergo modifications to serve similar functions. This phenomenon is called [[convergent evolution]]. Similar structures, physiological processes or mode of life in organisms apparently bearing no close phylogenetic links but showing adaptations to perform the same functions are described as [[analogy|analogous]], for example: | + | Under similar environmental conditions, fundamentally different structures in different groups of organisms may undergo modifications to serve similar functions. This phenomenon is called [[convergent evolution]]. Similar structures, physiological processes. or mode of life in organisms apparently bearing no close phylogenetic links but showing adaptations to perform the same functions are described as [[analogy|analogous]], for example: |

| − | * Wings of [[bat]]s, [[bird]]s and [[insect]]s; | + | * Wings of [[bat]]s, [[bird]]s. and [[insect]]s; |

* the jointed legs of [[insect]]s and [[vertebrate]]s; | * the jointed legs of [[insect]]s and [[vertebrate]]s; | ||

| − | * tail [[fin]] of [[fish]], [[whale]] and [[lobster]]; | + | * tail [[fin]] of [[fish]], [[whale]], and [[lobster]]; |

| − | * [[eye]]s of the [[vertebrate]]s and [[cephalopod]] | + | * [[eye]]s of the [[vertebrate]]s and [[cephalopod]] [[mollusk]]s ([[squid]] and [[octopus]]). Fig. 6 illustrates difference between an inverted and non-inverted [[retina]], the sensory cells lying beneath the nerve fibers. This results in the sensory cells being absent where the [[optic nerve]] is attached to the eye, thus creating a [[blind spot]]. The octopus eye has a non-inverted retina in which the sensory cells lie above the nerve fibers. There is therefore no blind spot in this kind of eye. Apart from this difference the two eyes are remarkably similar, an example of convergent evolution. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

====Vestigial organs==== | ====Vestigial organs==== | ||

| − | ''Main article: [[Vestigial | + | ''Main article: [[Vestigial organ]]'' |

| − | A further aspect of comparative anatomy is the presence of vestigial | + | A further aspect of comparative anatomy is the presence of [[vestigial organ]]s. [[Organ (anatomy)|Organs]] that are smaller and simpler in structure than corresponding parts in the ancestral species, and that are usually degenerated or underdeveloped, are called vestigial organs. From the point of view of descent with modification, the existence of vestigial organs can be explained in terms of changes in a descendant species, perhaps connected to changes in the environment or modes of life of the species. Those organs are thought to be functional in the ancestral species but have now become unnecessary and non-functional. Examples are the vestigial hind limbs of [[whale]]s, the [[haltere]] (vestigial hind [[wing]]s) of [[fly|flies]] and [[mosquito]]s, vestigial wings of flightless birds such as [[ostrich]]es, and the vestigial [[leaf|leaves]] of some [[xerophyte]]s (''e.g.'' [[cactus]]) and parasitic plants (''e.g.'' [[dodder]]). It must be noted however, that vestigial structures have lost the original function but may have another one. For example, the halteres in [[dipterist]]s help balance the insect while in flight and the wings of ostriches are used in [[mating ritual]]s. |

===Evidence from geographical distribution=== | ===Evidence from geographical distribution=== | ||

Revision as of 01:11, 24 July 2007

Evidence of evolution or evidence for evolution is any of an available body of facts or information that supports the evolutionary theory of descent with modification; the phrase sometimes is extended to include those facts that support the theory of modification through natural selection.

The theory of descent with modification and the theory of natural selection are the two cornerstone theories of Charles Darwin's overall theory of evolution. The theory of descent with modification deals with the pattern of evolution and essentially postulates that all organisms have descended from common ancestors by a continuous process of branching. The theory of natural selection deals with the process of evolution and is one possible mechanism offered for how changes systematically occur to arrive at the pattern, with natural selection being the directing or creative force.

In a broad sense, the term evolution itself simply refers to any heritable change in a population of organisms over time. Changes may be slight or large, but must be passed on to the next generation (or many generations) and must involve populations, not individuals. Thus, any observed change in gene frequencies, even simply the development of antibiotic resistance in a strain of bacteria from one generation to the next, constitutes evidence for evolution.

More generally, however, evidences of evolution are used in the sense of support for the theory of descent with modification or the theory of natural selection in terms of macroevolutionary changes. Macroevolution refers to evolution that occurs above the level of species, such as the origin of new designs (feathers, vertebrates from invertebrates, jaws in fish), large scale events (extinction of dinosaurs), broad trends (increase in brain size in mammals), and major transitions (origin of higher-level phyla). This is one of two classes of evolutionary phenomena, the other being microevolution, which refers to events and processes at or below the level of species, such as changes of gene frequencies in a population and speciation phenomena. This article will deal with evidences for these two main theories on the macroevolutionary level.

There is a tendency to consider all evidences as support for the comprehensive theory of evolution that includes both the pattern of change and the mechanism of natural selection. However, direct evidences on the macroevolutionary level—such as fossil evidence, biogreography, homology, genetic—actually are limited only to support for the theory of descent with modification. Evidences specific for the theory of natural selection being applicable on the macroevolutionary level necessarily involves extrapolation from evidences on the microevolutionary level.

Overview

As broadly and commonly defined in the scientific community, the term evolution connotes heritable changes in populations of organisms over time, or changes in the frequencies of alleles over time. In this sense, the term does not specify any overall pattern of change through the ages, nor the process whereby change occurs.

However, the term evolution often is used with more narrow meanings. It is not uncommon to see the term equated to the specific theory that all organisms have descended from common ancestors, which is also known as the theory of descent with modification. Less frequently, evolution sometimes is used to refer to one explanation for the process by which change occurs, the theory of modification through natural selection. In addition, the term evolution occasionally is used with reference to a comprehensive theory that includes both the non-causal pattern of descent with modification and the causal mechanism of natural selection.

In reality, in Darwin's comprehensive theory of evolution, there actually can be elucidated at least five major, largely independent theories, including these two main theories (Mayr 1982). Other theories offered by Darwin deal with (3) evolution as such (the fact of evolution), (4) the gradualness of evolution, and (5) populational speciation.

The "theory of descent with modification" is the major kinematic theory that deals with the pattern of evolution—that is, it treats non-causal relations between ancestral and descendent species, orders, phyla, and so forth. The theory of descent with modification, also called the "theory of common descent," essentially postulates that all organisms have descended from common ancestors by a continuous process of branching. In other words, all life evolved from one kind of organism or from a few simple kinds, and each species arose in a single geographic location from another species that preceded it in time. Each group of organisms shares a common ancestor.

One of the major contributions of Charles Darwin was to catalogue evidence for the theory of descent with modification, particularly in his book Origin of Species. Over time, evolutionists have marshaled substantial evidence for the theory of descent with modification. That is, the "pattern of evolution" is well documented by the fossil record, the distribution patterns of existing species, methods of dating fossils, and comparison of homologous structures.

Evidence is so overwhelming for the theory of descent with modification that only religious fundamentalists have attempted to challenge this theory. Among these are the “scientific creationists.” Scientific creationists are a specific group of creationists who maintain that modern organisms did not descend from common ancestors, and that their only historical connectedness is in the mind of God. Instead, scientific creationists promulgate the view that living organisms are immutable, and were all created by God in a short time period, on a earth whose age is generally measured in 1000s of years. The substantial fossil record is dismissed in various ways, including as a trick of God and as an artifact from the Great Flood (with some organisms sinking faster than others and thus on a lower fossil plane). Although some individual presentations by scientific creationists are quite sophisticated, the overall theory of scientific creationism runs counter to an enormous body of evidence and thus is strongly criticized by most of the scientific community.

The second major evolutionary theory is the "theory of modification through natural selection," also known as the "theory of natural selection." This is a dynamic theory that involves mechanisms and causal relationships; in other words, the "process" by which evolution took place to arrive at the pattern. Natural selection may be defined as the mechanism whereby biological individuals that are endowed with favorable or deleterious traits reproduce more or less than other individuals that do not possess such traits. According to this theory, natural selection is the directing or creative force of evolution.

The theory of natural selection was the most revolutionary and controversial concept advanced by Darwin. It is this theory of natural selection that has the three radical components of (a) purposelessness (no higher purpose, just the struggle of individuals to survive and reproduce); (b) philosophical materialism (matter is seen as the ground of all existence with spirit and mind being produced by or a function of the material brain); and (c) the view that evolution is not progressive from lower to higher, but just an adaptation to local environments; it could form a man with his superior brain or a parasite, but no one could say which is higher or lower ((Luria, Gould, and Singer 1981). (See Charles Darwin for an explanation of these three concepts.)

In reality, most evidences that are presented are actually for the theory of descent with modification. Concrete evidence for the theory of modification by natural selection is limited to microevolution—that is, within populations or species. For example, it is observed in the increased pesticide resistance in a species of bacteria. Artificial selection within populations or species also provides evidence, such as in the production of various breeds of animals by selective breeding, or and varieties of plants by selective cultivation. However, the evidence that natural selection directs the major transitions between taxa and originates new designs (macroevolution) necessarily involves extrapolation from these evidences on the microevolutionary level. That is, it is inferred that if moths can change their color in 50 years, then new designs or entire new genera can originate over millions of years. If geneticists see population changes for fruit flies in laboratory bottles, then given eons of time, birds can be built from reptiles and fish with jaws from jawless ancestors.

The following are evidences of evolution for the theory of descent with modification and the theory of natural selection, with a focus on macroevolutionary changes.

Evidence for the theory of descent with modification

For the broad concept of evolution ("any heritable change in a population of organisms over time"), evidences of evolution are readily apparent on a microevolutionary level. Evidences include observed changes in domestic crops (creating a variety of maize with greater resistance to disease), bacterial strains (development of strains with resistance to antibiotics), laboratory animals (structural changes in fruit flies), and flora and fauna in the wild (color change in particular populations of peppered moths and polyploidy in plants).

However, it was Charles Darwin, in the Origin of Species, who first marshaled considerable evidences for the theory of descent with modification on the macroevolutionary level. He did this within such areas as paleontology, biogeography, morphology, and embryology. Many of these areas continue to provide the most convincing proofs of descent with modification even today (Mayr 1982; Mayr 2001). Supplementing these areas are molecular evidences.

Stephen Jay Gould (1983) notes that the best support for the theory of descent with modification actually comes from the observation of imperfections of nature, rather than perfect adaptations:

All of the classical arguments for evolution are fundamentally arguments for imperfections that reflect history. They fit the pattern of observing that the leg of Reptile B is not the best for walking, because it evolved from Fish A. In other words, why would a rat run, a bat fly, a porpoise swim and a man type all with the same structures utilizing the same bones unless inherited from a common ancestor?

Evidence from paleontology

Overview

Fossil evidence of prehistoric organisms has been found all over the Earth. Fossils are traces of once living organisms. Fossilization on an organism is an uncommon occurrence, usually requiring hard parts (like bone) and death where sediments or volcanic ash may be deposited. Fossil evidence of organisms without hard body parts, such as shell, bone, teeth, and wood stems, is sparse, but exists in the form of ancient microfossils and the fossilization of ancient burrows and a few soft-bodied organisms. Some insects have been preserved in resin. The age of fossils can often be deduced from the geologic context in which they are found (the strata); and their age also can be determined with radiometric dating.

The comparison of fossils of extinct organisms in older geological strata with fossils found in more recent strata or with living organisms is considered strong evidence of descent with modification. Fossils found in more recent strata are often very similar to, or indistinguishable from living species, whereas the older the fossils the more different they are from living organisms or recent fossils. In addition, fossil evidence reveals that species of greater complexity have appeared on the earth over time, beginning in the Precambrian era some 600 millions of years ago with the first eukaryotes. The fossil records support the view that there is orderly progression in which each stage emerges from, or builds upon, preceding stages.

Fossils

When organisms die, they often decompose rapidly or are consumed by scavengers, leaving no permanent evidences of their existence. However, occasionally, some organisms are preserved. The remains or traces of organisms from a past geologic age embedded in rocks by natural processes are called fossils. They are extremely important for understanding the evolutionary history of life on Earth, as they provide direct evidence of evolution and detailed information on the ancestry of organisms. Paleontology is the study of past life based on fossil records and their relations to different geologic time periods.

For fossilization to take place, the traces and remains of organisms must be quickly buried so that weathering and decomposition do not occur. Skeletal structures or other hard parts of the organisms are the most commonly occurring form of fossilized remains (Paul 1998; Behrensmeyer 1980; Martin 1999). There are also some trace "fossils" showing molds, cast, or imprints of some previous organisms.

As an animal dies, the organic materials gradually decay, such that the bones become porous. If the animal is subsequently buried in mud, mineral salts will infiltrate into the bones and gradually fill up the pores. The bones will harden into stones and be preserved as fossils. This process is known as petrification. If dead animals are covered by wind-blown sand, and if the sand is subsequently turned into mud by heavy rain or floods, the same process of mineral infiltration may occur. Apart from petrification, the dead bodies of organisms may be well preserved in ice, in hardened resin of coniferous trees (amber), in tar, or in anaerobic, acidic peat. Examples of trace fossils, an impression of a form, include leaves and footprints, the fossils of which are made in layers that then harden.

Fossils are important for estimating when various lineages developed. As fossilization is an uncommon occurrence, usually requiring hard body parts and death near a site where sediments are being deposited, the fossil record only provides sparse and intermittent information about the evolution of life. Evidence of organisms prior to the development of hard body parts such as shells, bones, and teeth is especially scarce, but exists in the form of ancient microfossils, as well as impressions of various soft-bodied organisms

Fossil records

It is possible to observe sequences of changes over time by arranging fossil records in a chronological sequence. Such a sequence can be determined because fossils are mainly found in sedimentary rock. Sedimentary rock is formed by layers of silt or mud on top of each other; thus, the resulting rock contains a series of horizontal layers, or strata. Each layer contains fossils that are typical for a specific time period during which they were made. The lowest strata contain the oldest rock and the earliest fossils, while the highest strata contain the youngest rock and more recent fossils.

A succession of animals and plants can also be seen from fossil records. Fossil evidence supports the theory that organisms tend to progressively increase in complexity. By studying the number and complexity of different fossils at different stratigraphic levels, it has been shown that older fossil-bearing rocks contain fewer types of fossilized organisms, and they all have a simpler structure, whereas younger rocks contain a greater variety of fossils, often with increasingly complex structures.

In the past, geologists could only roughly estimate the ages of various strata and the fossils found. They did so, for instance, by estimating the time for the formation of sedimentary rock layer by layer. Today, by measuring the proportions of radioactive and stable elements in a given rock, the ages of fossils can be more precisely dated by scientists. This technique is known as radiometric dating.

Throughout the fossil record, many species that appear at an early stratigraphic level disappear at a later level. This is interpreted in evolutionary terms as indicating the times at which species originated and became extinct. Geographical regions and climatic conditions have varied throughout the Earth's history. Since organisms are adapted to particular environments, the constantly changing conditions favored species that adapted to new environments.

According to fossil records, some modern species of plants and animals are found to be almost identical to the species that lived in ancient geological ages. They are existing species of ancient lineages that have remained morphologically (and probably also physiologically) somewhat unchanged for a very long time. Consequently, they are called "living fossils" by laypeople. Examples of "living fossils" include the tuatara, the nautilus, the horseshoe crab, the coelacanth, the ginkgo, the Wollemi pine, and the metasequoia.

Despite the relative rarity of suitable conditions for fossilization, approximately 250,000 fossil species are known (Gore 2006). The number of individual fossils this represents varies greatly from species to species, but many millions of fossils have been recovered: for instance, more than three million fossils from the last Ice Age have been recovered from the La Brea Tar Pits (NHMLA 2007) in Los Angeles. Many more fossils are still in the ground, in various geological formations known to contain a high fossil density, allowing estimates of the total fossil content of the formation to be made. An example of this occurs in South Africa's Beaufort Formation (part of the Karoo Supergroup, which covers most of South Africa), which is rich in vertebrate fossils, including therapsids (reptile/mammal transitional forms) (Kazlev 2002).

Evolution of the horse

Due to a substantial fossil record found in North American sedimentary deposits from the early Eocene to the present, the horse is considered to provide one of the best examples of evolutionary history (phylogeny).

This evolutionary sequence starts with a small animal called the Hyracotherium that lived in North America about 54 million years ago, then spread across to Europe and Asia. Fossil remains of Hyracotherium show it to have differed from the modern horse in three important respects: it was a small animal (the size of a fox), lightly built and adapted for running; the limbs were short and slender, and the feet elongated so that the digits were almost vertical, with four digits in the forelimbs and three digits in the hindlimbs; and the incisors were small, the molars having low crowns with rounded cusps covered in enamel.

The probable course of development of horses from Hyracotherium to Equus (the modern horse) involved at least 12 genera and several hundred species. The major trends seen in the development of the horse to changing environmental conditions may be summarized as follows:

- Increase in size (from 0.4 m to 1.5 m);

- Lengthening of limbs and feet;

- Reduction of lateral digits;

- Increase in length and thickness of the third digit;

- Increase in width of incisors;

- Replacement of premolars by molars; and

- Increases in tooth length, crown height of molars.

A dominant genus from each geological period has been selected to show the progressive development of the horse. However, it is important to note that there is no evidence that the forms illustrated are direct descendants of each other, even though they are related.

Limitations of fossil evidence

The fossil record is an important source for scientists when speculating on the evolutionary history of organisms. However, one of the problems with fossil evidence is the general lack of gradually sequenced intermediary forms. There are some fossil lineages that appear quite well-represented, such as from therapsid reptiles to the mammals, and between what is considered land-living ancestors of the whales and their ocean-living descendants (Mayr 2001). The transition from an ancestral horse (Eohippus) and the modern horse (Equus) is also significant, and Archaeopteryx has been postulated as fitting the gap between reptiles and birds. But generally, paleontologists do not find a steady change from ancestral forms to descendant forms, but rather discontinuities, or gaps in most every phyletic series (Mayr 2002). This has been explained both by the incompleteness of the fossil record and by proposals of speciation that involve short periods of time, rather than millions of years. (Notably, there are also gaps between living organisms, with a lack of intermediaries between whales and terrestrial mammals, between reptiles and birds, and between flowering plants and their closest relatives (Mayr 2002).) Archaeopteryx has recently come under criticism as a transitional fossil between reptiles and birds (Wells 2000).

There is a gap of about 100 million years between the early Cambrian period and the later Ordovician period. The early Cambrian period was the period from which numerous fossils of sponges, cnidarians (e.g., jellyfish), echinoderms (e.g., eocrinoids), molluscs (e.g., snails) and arthropods (e.g., trilobites) are found. In the later Ordovician period, the first animal that really possessed the typical features of vertebrates, the Australian fish, Arandaspis appeared. Thus few, if any, fossils of an intermediate type between invertebrates and vertebrates have been found, although likely candidates include the Burgess Shale animal, Pikaia gracilens, and its Maotianshan Shales relatives, Myllokunmingia, Yunnanozoon, Haikouella lanceolata, and Haikouichthys.

Some of the reasons for the incompleteness of fossil records are:

- In general, the probability that an organism becomes fossilized after death is very low;

- Some species or groups are less likely to become fossils because they are soft-bodied;

- Some species or groups are less likely to become fossils because they live (and die) in conditions that are not favorable for fossilization to occur in;

- Many fossils have been destroyed through erosion and tectonic movements;

- Some fossil remains are complete, but most are fragmentary;

- Some evolutionary change occurs in populations at the limits of a species' ecological range, and as these populations are likely to be small, the probability of fossilization is lower (punctuated equilibrium);

- Similarly, when environmental conditions change, the population of a species is likely to be greatly reduced, such that any evolutionary change induced by these new conditions is less likely to be fossilized;

- Most fossils convey information about external form, but little about how the organism functioned;

- Using present-day biodiversity as a guide, this suggests that the fossils unearthed represent only a small fraction of the large number of species of organisms that lived in the past.

The fact that the fossil evidence supports the view that species tend to remain stable throughout their existence and that new species appear suddenly is not problematic for the theory of descent with modification, but only with Darwin's concept of gradualism. The sudden appearance of forms, however, is consistent with religious views that descent with modification involved creative energy directing the variation or changes rather than non-purposeful natural selection.

Evidence from comparative anatomy

Overview

The study of comparative anatomy also yields evidence for the theory of descent with modification. For one, there are structures in diverse species that have similar internal organization yet perform different functions. Vertebrate limbs are a common example of such homologous structures. Bat wings, for example, are very similar to human hands. Also similar are the forelimbs of the penguin, the porpoise, the rat, and the alligator. In addition, these features derive from the same structures in the embryo stage. As queried earlier, “why would a rat run, a bat fly, a porpoise swim and a man type” all with limbs using the same bone structure if not coming from a common ancestor, since these are surely not the most ideal structures for each use (Gould 1983).

Likewise, a structure may exist with little or no purpose in one organism, yet the same structure has a clear purpose in other species. These features are called vestigial organs or vestigial characters. The human wisdom teeth and appendix are common examples. Likewise, some snakes have pelvic bones and limb bones, and some blind salamanders and blind cave fish have eyes. Such features would be the prediction of the theory of descent with modification, suggesting that they share a common ancestry with organisms that have the same structure, but which is functional.

For the point of view of classification, it can be observed that various species exhibit a sense of "relatedness," such as various catlike mammals can be put in the same family (Felidae), dog-like mammals in the same family (Canidae), and bears in the same family (Ursidae), and so forth, and then these and other similar mammals can be combined into the same order (Carnivora). This sense of relatedness, from external features, fits the expectations of the theory of descent with modification.

Comparative study of the anatomy of groups of plants reveals that certain structural features are basically similar. For example, the basic structure of all flowers consists of sepals, petals, stigma, style and ovary; yet the size, color, number of parts, and specific structure are different for each individual species.

In a more general sense, all organisms utilize cells as the basic unit of life and pass on their heredity using a nearly universal genetic code, reflecting the likelihood that common origin.

Phylogeny, the study of the ancestry (pattern and history) of organisms, yields a phylogenetic tree to show such relatedness (or a cladogram in other taxonomic disciplines).

Homologous structures

If widely separated groups of organisms are originated from a common ancestry, they are expected to have certain basic features in common. The degree of resemblance between two organisms should indicate how closely related they are in evolution:

- Groups with little in common are assumed to have diverged from a common ancestor much earlier in geological history than groups which have a lot in common;

- In deciding how closely related two animals are, a comparative anatomist looks for structures that are fundamentally similar, even though they may serve different functions in the adult.

- In cases where the similar structures serve different functions in adults, it may be necessary to trace their origin and embryonic development. A similar developmental origin suggests they are the same structure, and thus likely to be derived from a common ancestor.

In biology, homology is commonly defined as any similarity between structures that is attributed to their shared ancestry. There are examples in different levels of organization. Entire anatomical structures that are similar in different biological taxa (species, genera, etc.) would be termed homologous if they evolved from the same structure in some ancestor, and partial sequences in DNA or protein would be similarly labeled if common ancestry was the cause.

This is a redefinition from the classical understanding of the term, which predates Darwin's theory of evolution, being coined by Richard Owen in the 1840s. Historically, homology was defined as similarity in structure and position, such as the pattern of bones in a bat's wing and those in a porpoise's flipper (Wells 2000). Conversely, the term analogy signified functional similarity, such as the wings of a bird and those of a butterfly.

Homology in the classical sense, as similarity in structure and position of anatomical features between different organisms, was an important evidence used by Darwin. Similarity in structures between diverse organisms—such as the similar skeletal structures (utilizing same bones) of the forelimbs of humans, bats, whales, birds, dogs, and alligators—provides evidence of evolution by common descent (theory of descent with modification). There is evidence that new forms develop on the foundation of earlier stages.

However, it would be incorrect to state that homology, as presently defined, provides evidence of evolution because it would be circular reasoning, with homology defined as similarity due to shared ancestry. Mayr (1982) states, "After 1859 there has been only one definition of homologous that makes biological sense... Attributes of two organisms are homologous when they are derived from an equivalent characteristics of the common ancestor."

When a group of organisms share a homologous structure which is specialized to perform a variety of functions in order to adapt different environmental conditions and modes of life are called adaptive radiation. The gradual spreading of organisms with adaptive radiation is known as divergent evolution.

Homology: Pentadactyl limb

The pattern of limb bones called pentadactyl limb is an example of homologous structures (Fig. 5a). This pattern is found in all classes of tetrapods (i.e. from amphibians to mammals). It can even be traced back to the fins of certain fossil fishes from which the first amphibians are thought to have evolved. The limb has a single proximal bone (humerus), two distal bones (radius and ulna), a series of carpals (wrist bones), followed by five series of metacarpals (palm bones) and phalanges (digits). Throughout the tetrapods, the fundamental structures of pentadactyl limbs are the same, indicating that they originated from a common ancestor. But it is considered that in the course of evolution, these fundamental structures have been modified. They have become superficially different and unrelated structures to serve different functions in adaptation to different environments and modes of life. This phenomenon is clearly shown in the forelimbs of mammals. For example:

- In the monkey, the forelimbs are much elongated to form a grasping hand for climbing and swinging among trees.

- In the pig, the first digit is lost, and the second and fifth digits are reduced. The remaining two digits are longer and stouter than the rest and bear a hoof for supporting the body.

- In the horse, the forelimbs are adapted for support and running by great elongation of the third digit bearing a hoof.

- The mole has a pair of short, spade-like forelimbs for burrowing.

- The anteater uses its enlarged third digit for tearing down ant hills and termite nests.

- In the whale, the forelimbs become flippers for steering and maintaining equilibrium during swimming.

- In the bat, the forelimbs have turned into wings for flying by great elongation of four digits, and the hook-like first digit remains free for hanging from trees.

Homology: Insect mouthparts

In insects,the basic structures of the mouthparts are the same, including a labrum (upper lip), a pair of mandibles, a hypopharynx (floor of mouth), a pair of maxillae, and a labium. These structures are enlarged and modified; others are reduced and lost. The modifications enable the insects to exploit a variety of food materials (Fig. 5b):

(A) Primitive state — biting and chewing: e.g., grasshopper. Strong mandibles and maxillae for manipulating food.

(B) Ticking and biting: e.g., honeybee. Labium long to lap up nectar; mandibles chew pollen and mold wax.

(C) Sucking: e.g., butterfly. Labrum reduced; mandibles lost; maxillae long forming sucking tube.

(D) Piercing and sucking, e.g, female mosquito. Labrum and maxillae form tube; mandibles form piercing stylets; labrum grooved to hold other parts.

Homology: Other arthropod appendages

Insect mouthparts and antennae are considered homologues of insect legs. Parallel developments are seen in some arachnids: The anterior pair of legs may be modified as analogues of antennae, particularly in whip scorpians, which walk on six legs. These developments provide support for the theory that complex modifications often arise by duplication of components, with the duplicates modified in different directions.

Analogous structures and convergent evolution

Under similar environmental conditions, fundamentally different structures in different groups of organisms may undergo modifications to serve similar functions. This phenomenon is called convergent evolution. Similar structures, physiological processes. or mode of life in organisms apparently bearing no close phylogenetic links but showing adaptations to perform the same functions are described as analogous, for example:

- Wings of bats, birds. and insects;

- the jointed legs of insects and vertebrates;

- tail fin of fish, whale, and lobster;

- eyes of the vertebrates and cephalopod mollusks (squid and octopus). Fig. 6 illustrates difference between an inverted and non-inverted retina, the sensory cells lying beneath the nerve fibers. This results in the sensory cells being absent where the optic nerve is attached to the eye, thus creating a blind spot. The octopus eye has a non-inverted retina in which the sensory cells lie above the nerve fibers. There is therefore no blind spot in this kind of eye. Apart from this difference the two eyes are remarkably similar, an example of convergent evolution.

Vestigial organs

Main article: Vestigial organ

A further aspect of comparative anatomy is the presence of vestigial organs. Organs that are smaller and simpler in structure than corresponding parts in the ancestral species, and that are usually degenerated or underdeveloped, are called vestigial organs. From the point of view of descent with modification, the existence of vestigial organs can be explained in terms of changes in a descendant species, perhaps connected to changes in the environment or modes of life of the species. Those organs are thought to be functional in the ancestral species but have now become unnecessary and non-functional. Examples are the vestigial hind limbs of whales, the haltere (vestigial hind wings) of flies and mosquitos, vestigial wings of flightless birds such as ostriches, and the vestigial leaves of some xerophytes (e.g. cactus) and parasitic plants (e.g. dodder). It must be noted however, that vestigial structures have lost the original function but may have another one. For example, the halteres in dipterists help balance the insect while in flight and the wings of ostriches are used in mating rituals.

Evidence from geographical distribution

Biologists have discovered many puzzling facts about the presence of certain species on various continents and islands (biogeography).

Continental distribution

All organisms are adapted to their environment to a greater or lesser extent. If the abiotic and biotic factors within a habitat are capable of supporting a particular species in one geographic area, then one might assume that the same species would be found in a similar habitat in a similar geographic area, e.g. in Africa and South America. This is not the case. Plant and animal species are discontinuously distributed throughout the world:

- Africa has short-tailed (Old World) monkeys, elephants, lions and giraffes.

- South America has long-tailed monkeys, cougars, jaguars and llamas.

Even greater differences can be found if Australia is taken into consideration though it occupies the same latitude as South America and Africa. Marsupials like the kangaroo can be found in Australia, but are totally absent from Africa and are only represented by the opossum in South America and the Virginia Opossum in North America:

- The echidna and platypus, the only living representatives of primitive egg-laying mammals (monotremes), can be found only in Australia and are totally absent in the rest of the world.

- On the other hand, Australia has very few placental mammals except those that have been introduced by human beings.

Explanation

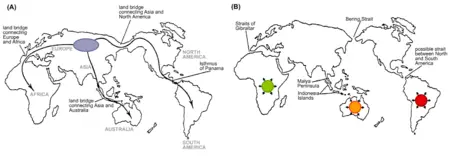

The main groups of modern mammal arose in Northern Hemisphere and subsequently migrated to three major directions:

- to South America via the land bridge in the Bering Strait and Isthmus of Panama; A large number of families of South American marsupials became extinct as a result of competition with these North American counterparts.

- to Africa via the Strait of Gibraltar; and

- to Australia via South East Asia to which it was at one time connected by land

The shallowness of the Bering Strait would have made the passage of animals between two northern continents a relatively easy matter, and it explains the present-day similarity of the two faunas. But once they had got down into the southern continents, they presumably became isolated from each other by various types of barriers.

- The submerging of the Isthmus of Panama: isolates the South American fauna

- the Mediterranean Sea and the North African desert: partially isolate the African fauna; and

- the submerging of the original connection between Australia and South East Asia: isolates the Australian fauna

Once isolated, the animals in each continent have shown adaptive radiation (Fig. 7) to evolve along their own lines.

Evidence for migration and isolation

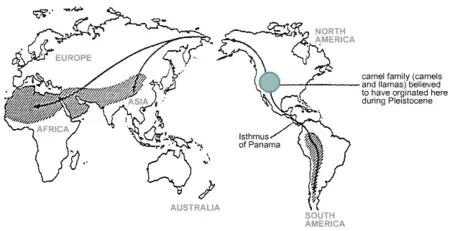

The fossil record for the camel indicated that evolution of camels started in North America, from which they migrated across the Bering Strait into Asia and hence to Africa, and through the Isthmus of Panama into South America. Once isolated, they evolved along their own lines, giving the modern camel in Asia and Africa and llama in South America.

Continental drift

The same kinds of fossils are found from areas known to be adjacent to one another in the past but which, through the process of continental drift, are now in widely divergent geographic locations. For example, fossils of the same types of ancient amphibians, arthropods and ferns are found in South America, Africa, India, Australia and Antarctica, which can be dated to the Paleozoic Era, at which time these regions were united as a single landmass called Gondwana. [4] Sometimes the descendants of these organisms can be identified and show unmistakable similarity to each other, even though they now inhabit very different regions and climates.

Oceanic island distribution

Most small isolated islands only have native species that could have arrived by air or water; like birds, insects and turtles. The few large mammals present today were brought by human settlers in boats. Plant life on remote and recent volcanic islands like Hawaii could have arrived as airborne spores or as seeds in the droppings of birds. After the explosion of Krakatoa a century ago and the emergence of a steaming, lifeless remnant island called Anak Krakatoa (child of Krakatoa), plants arrived within months and within a year there were moths and spiders that had arrived by air. The island is now ecologially hard to distinguish from those around it that have been there for millions of years.

Evidence from comparative physiology and biochemistry

- See also: Archaeogenetics, Common descent, Last universal ancestor, Most recent common ancestor, Nothing in Biology Makes Sense Except in the Light of Evolution, Speciation, Timeline of evolution, Timeline of human evolution, Universal Code (Biology)

Evolution of widely distributed proteins and molecules

All known extant organisms make use of DNA and/or RNA. ATP is used as metabolic currency by all extant life. The Genetic code is the same for almost every organism, meaning that a piece of RNA in a bacterium codes for the same protein as in a human cell.

A classic example of biochemical evidence for evolution is the variance of the protein Cytochrome c in living cells. The variance of cytochrome c of different organisms is measured in the number of differing amino acids, each differing amino acid being a result of a base pair substitution, a mutation. If each differing amino acid is assumed to be the result of one base pair substitution, it can be calculated how long ago the two species diverged by multiplying the number of base pair substitutions by the estimated time it takes for a substituted base pair of the cytochrome c gene to be successfully passed on. For example, if the average time it takes for a base pair of the cytochrome c gene to mutate is N years, the number of amino acids making up the cytochrome c protein in monkeys differ by one from that of humans, this leads to the conclusion that the two species diverged N years ago.

Comparison of the DNA sequences allows organisms to be grouped by sequence similarity, and the resulting phylogenetic trees are typically congruent with traditional taxonomy, and are often used to strengthen or correct taxonomic classifications. Sequence comparison is considered a measure robust enough to be used to correct erroneous assumptions in the phylogenetic tree in instances where other evidence is scarce. For example, neutral human DNA sequences are approximately 1.2% divergent (based on substitutions) from those of their nearest genetic relative, the chimpanzee, 1.6% from gorillas, and 6.6% from baboons.[1] Genetic sequence evidence thus allows inference and quantification of genetic relatedness between humans and other apes.[2][3] The sequence of the 16S rRNA gene, a vital gene encoding a part of the ribosome, was used to find the broad phylogenetic relationships between all extant life. The analysis, originally done by Carl Woese, resulted in the three-domain system, arguing for two major splits in the early evolution of life. The first split led to modern Bacteria and the subsequent split led to modern Archaea and Eukaryote.

The proteomic evidence also supports the universal ancestry of life. Vital proteins, such as the ribosome, DNA polymerase, and RNA polymerase, are found in everything from the most primitive bacteria to the most complex mammals. The core part of the protein is conserved across all lineages of life, serving similar functions. Higher organisms have evolved additional protein subunits, largely affecting the regulation and protein-protein interaction of the core. Other overarching similarities between all lineages of extant organisms, such as DNA, RNA, amino acids, and the lipid bilayer, give support to the theory of common descent. The chirality of DNA, RNA, and amino acids is conserved across all known life. As there is no functional advantage to right- or left-handed molecular chirality, the simplest hypothesis is that the choice was made randomly by early organisms and passed on to all extant life through common descent. Further evidence for reconstructing ancestral lineages comes from junk DNA such as pseudogenes, "dead" genes which steadily accumulate mutations.[4]

There is also a large body of molecular evidence for a number of different mechanisms for large evolutionary changes, among them: genome and gene duplication, which facilitates rapid evolution by providing substantial quantities of genetic material under weak or no selective constraints; horizontal gene transfer, the process of transferring genetic material to another cell that is not an organism's offspring, allowing for species to acquire beneficial genes from each other; and recombination, capable of reassorting large numbers of different alleles and of establishing reproductive isolation. The Endosymbiotic theory explains the origin of mitochondria and plastids (e.g. chloroplasts), which are organelles of eukaryotic cells, as the incorporation of an ancient prokaryotic cell into ancient eukaryotic cell. Rather than evolving eukaryotic organelles slowly, this theory offers a mechanism for a sudden evolutionary leap by incorporating the genetic material and biochemical composition of a separate species. Evidence supporting this mechanism has recently been found in the protist Hatena: as a predator it engufes a green algae cell, which subsequently behaves as an endosymbiont, nourishing Hatena, which in turn loses it's feeding apparatus and behaves as an autotroph.[5][6]

Since metabolic processes do not leave fossils, research into the evolution of the basic cellular processes is done largely by comparison of existing organisms. Many lineages diverged when new metabolic processes appeared, and it is theoretically possible to determine when certain metabolic processes appeared by comparing the traits of the descendants of a common ancestor or by detecting their physical manifestations. As an example, the appearance of oxygen in the earth's atmosphere is linked to the evolution of photosynthesis.

Evidence for theory of natural selection

Microevolutionar level, evidences are common On macroevolutionary level, extrapolations artificial selection

The conventional view of evolution is that macroevolution is simply microevolution continued on a larger scale, over large expanses of time. That is, if one observes a change in the frequencies of spots in guppies within 15 generations, as a result of selective pressures applied by the experimenter in the laboratory, then over millions of years one can get amphibians and reptiles evolving from fish due to natural selection. If a change in beak size of finches is seen in the wild in 30 years due to natural selection, then natural selection can result in new phyla if given eons of time.

Indeed, the only concrete evidence for the theory of modification by natural selection—that natural selection is the causal agent of both microevolutionary and macroevolutionary change— comes from microevolutionary evidences, which are then extrapolated to macroevolution. However, the validity of making this extrapolation has been challenged from the time of Darwin, and remains controversial today, even among top evolutionists. Many see microevolution as decoupled from macroevolution in terms of mechanisms, with natural selection being incapable of being the creative force of macroevolutionary change. (See macroevolution and natural selection.)

On the microevolutionary level (change within species), there are evidences that natural selection can produce evolutionary change. For example, changes in gene frequencies can be observed in populations of fruit flies exposed to selective pressures in the laboratory environment. Likewise, systematic changes in various phenotypes within a species, such as color changes in moths, can be observed in field studies. However, evidence that natural selection is the directive force of change in terms of the origination of new designs (such as the development of feathers) or major transitions between higher taxa (such as the evolution of land-dwelling vertebrates from fish) is not observable. Evidence for such macroevolutionary change is limited to extrapolation from changes on the microevolutionary level. A number of top evolutionists, including Gould, challenge the validity of making such extrapolations.

In addition to the lack of evidence for natural selection being the causal agent of change on macroevolutionary levels, as noted above, there are fundamental challenges to the theory of natural selection itself. These come from both the scientific and religious communities.

Such challenges to the theory of natural selection are not a new development. Unlike the theory of descent with modification, which was accepted by the scientific community during Darwin's time and for which substantial evidences have been marshaled, the theory of natural selection was not widely accepted until the mid-1900s and remains controversial even today.

In some cases, key arguments against natural selection being the main or sole agent of evolutionary change come from evolutionary scientists. One concern for example, is whether the origin of new designs and evolutionary trends (macroevolution) can be explained adequately as an extrapolation of changes in gene frequencies within populations (microevolution) (Luria, Gould, and Singer 1981). (See macroevolution for an overview of such critiques, including complications relating to the rate of observed macroevolutionary changes.)

Historically, the strongest opposition to Darwinism, in the sense of being a synonym for the theory of natural selection, has come from those advocating religious viewpoints. In essence, the chance component involved in the creation of new designs, which is inherent in the theory of natural selection, runs counter to the concept of a Supreme Being who has designed and created humans and all phyla. Chance (stochastic processes) is centrally involved in the theory of natural selection. As noted by eminent evolutionist Ernst Mayr (2001), chance plays an important role in two steps. First, the production of genetic variation "is almost exclusively a chance phenomena." Secondly, chance plays an important role even in "the process of the elimination of less fit individuals," and particularly during periods of mass extinction.

This element of chance counters the view that the development of new evolutionary designs, including humans, was a progressive, purposeful creation by a Creator God. Rather than the end result, according to the theory of natural selection, human beings were an accident, the end of a long, chance-filled process involving adaptations to local environments. There is no higher purpose, no progressive development, just materialistic forces at work. The observed harmony in the world becomes an artifact of such adaptations of organisms to each other and to the local environment. Such views are squarely at odds with many religious interpretations.

A key point of contention between the worldview is, therefore, the issue of variability—its origin and selection. For a Darwinist, random genetic mutation provides a mechanism of introducing novel variability, and natural selection acts on the variability. For those believing in a creator God, the introduced variability is not random, but directed by the Creator, although natural selection may act on the variability, more in the manner of removing unfit organisms than in any creative role. Some role may also be accorded differential selection, such as mass extinctions. Neither of these worldviews—random variation and the purposeless, non-progressive role of natural selection, or purposeful, progressive variation—are conclusively proved or unproved by scientific methodology, and both are theoretically possible.

There are some scientists who feel that the importance accorded to genes in natural selection may be overstated. According to Jonathan Wells, genetic expression in developing embryos is impacted by morphology as well, such as membranes and cytoskeletal structure. DNA is seen as providing the means for coding of the proteins, but not necessarily the development of the embryo, the instructions of which must reside elsewhere. It is possible that the importance of sexual reproduction and genetic recombination in introducing variability also may be understated.

The history of conflict between Darwinism and religion often has been exacerbated by confusion and dogmatism on both sides. Evolutionary arguments often are set up against the straw man of a dogmatic, biblical fundamentalism in which God created each species separately and the earth is only 6,000 years old. Thus, an either-or dichotomy is created, in which one believes either in the theory of natural selection or an earth only thousands of years old. However, young-earth creationism is only a small subset of the diversity of religious belief, and theistic, teleological explanations of the origin of species may be much more sophisticated and aligned with scientific findings. On the other hand, evolutionary adherents have sometimes presented an equally dogmatic front, refusing to acknowledge well thought out challenges to the theory of natural selection, or allowing for the possibility of alternative, theistic presentations.

Evidence from antibiotic and pesticide resistance

The development and spread of antibiotic resistant bacteria, like the spread of pesticide resistant forms of plants and insects is evidence for evolution of species, and of change within species. Thus the appearance of vancomycin resistant Staphlococcus aureus, and the danger it poses to hospital patients is a direct result of evolution through natural selection. Similarly the appearance of DDT resistance in various forms of Anopheles mosqitoes, and the appearance of myxomatosis resistance in breeding rabbit populations in Australia, are all evidence of the existence of evolution in situations of evolutionary selection pressure in species in which generations occur rapidly.

An example: antibiotic resistance

A well-known example of natural selection in action is the development of antibiotic resistance in microorganisms. Antibiotics have been used to fight bacterial diseases since the discovery of penicillin in 1928 by Alexander Fleming. However, the widespread use of antibiotics has led to increased microbial resistance against antibiotics, to the point that the methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) has been described as a "superbug" because of the threat it poses to health and its relative invulnerability to existing drugs.

Natural populations of bacteria contain, among their vast numbers of individual members, considerable variation in their genetic material, primarily as the result of mutations. When exposed to antibiotics, most bacteria die quickly, but some may have mutations that make them a little less susceptible. If the exposure to antibiotics is short, these individuals will survive the treatment. This selective elimination of "maladapted" individuals from a population is natural selection in action.

These surviving bacteria will then reproduce again, producing the next generation. Due to the elimination of the maladapted individuals in the past generation, this population contains more bacteria that have some resistance against the antibiotic. At the same time, new mutations occur, contributing new genetic variation to the existing genetic variation. Spontaneous mutations are very rare, very few have any effect at all, and usually any effect is deleterious. However, populations of bacteria are enormous, and so a few individuals may have beneficial mutations. If a new mutation reduces their susceptibility to an antibiotic, these individuals are more likely to survive when next confronted with that antibiotic. Given enough time, and repeated exposure to the antibiotic, a population of antibiotic-resistant bacteria will emerge.

Recently, several new strains of MRSA have emerged that are resistant to vancomycin and teicoplanin. This exemplifies a situation where medical researchers continue to develop new antibiotics that can kill the bacteria, and this leads to resistance to the new antibiotics. A similar situation occurs with pesticide resistance in plants and insects.

Evidence from studies of complex iteration

"It has taken more than five decades, but the electronic computer is now powerful enough to simulate evolution" [5] assisting bioinformatics in its attempt to solve biological problems.

Computer science allows the iteration of self changing complex systems to be studied, allowing a mathematically exact understanding of the nature of the processes behind evolution; providing evidence for the hidden causes of known evolutionary events. The evolution of specific cellular mechanisms like spliceosomes that can turn the cell's genome into a vast workshop of billions of interchangeable parts that can create tools that create tools that create tools that create us can be studied for the first time in an exact way.

For example, Christoph Adami et al. make this point in Evolution of biological complexity:

- To make a case for or against a trend in the evolution of complexity in biological evolution, complexity needs to be both rigorously defined and measurable. A recent information-theoretic (but intuitively evident) definition identifies genomic complexity with the amount of information a sequence stores about its environment. We investigate the evolution of genomic complexity in populations of digital organisms and monitor in detail the evolutionary transitions that increase complexity. We show that, because natural selection forces genomes to behave as a natural "Maxwell Demon," within a fixed environment, genomic complexity is forced to increase. [6]

For example, David J. Earl and Michael W. Deem make this point in Evolvability is a selectable trait:

- Not only has life evolved, but life has evolved to evolve. That is, correlations within protein structure have evolved, and mechanisms to manipulate these correlations have evolved in tandem. The rates at which the various events within the hierarchy of evolutionary moves occur are not random or arbitrary but are selected by Darwinian evolution. Sensibly, rapid or extreme environmental change leads to selection for greater evolvability. This selection is not forbidden by causality and is strongest on the largest-scale moves within the mutational hierarchy. Many observations within evolutionary biology, heretofore considered evolutionary happenstance or accidents, are explained by selection for evolvability. For example, the vertebrate immune system shows that the variable environment of antigens has provided selective pressure for the use of adaptable codons and low-fidelity polymerases during somatic hypermutation. A similar driving force for biased codon usage as a result of productively high mutation rates is observed in the hemagglutinin protein of influenza A. [7]

"Computer simulations of the evolution of linear sequences have demonstrated the importance of recombination of blocks of sequence rather than point mutagenesis alone. Repeated cycles of point mutagenesis, recombination, and selection should allow in vitro molecular evolution of complex sequences, such as proteins." [8] Evolutionary molecular engineering, also called directed evolution or in vitro molecular evolution involves the iterated cycle of mutation, multiplication with recombination, and selection of the fittest of individual molecules (proteins, DNA, and RNA). Natural evolution can be relived showing us possible paths from catalytic cycles based on proteins to based on RNA to based on DNA. [9] [10] [11] [12]

Evidence from speciation

Hawthorn fly

One example of evolution at work is the case of the hawthorn fly, Rhagoletis pomonella, also known as the apple maggot fly, which appears to be undergoing sympatric speciation.[7] Different populations of hawthorn fly feed on different fruits. A distinct population emerged in North America in the 19th century some time after apples, a non-native species, were introduced. This apple-feeding population normally feeds only on apples and not on the historically preferred fruit of hawthorns. The current hawthorn feeding population does not normally feed on apples. Some evidence, such as the fact that six out of thirteen allozyme loci are different, that hawthorn flies mature later in the season and take longer to mature than apple flies; and that there is little evidence of interbreeding (researchers have documented a 4-6% hybridization rate) suggests that this is occurring. The emergence of the new hawthorn fly is an example of evolution in progress.[8]

See also

- Human history

- Objections to evolution

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ Two sources: 'Genomic divergences between humans and other hominoids and the effective population size of the common ancestor of humans and chimpanzees'. and 'Quantitative Estimates of Sequence Divergence for Comparative Analyses of Mammalian Genomes' "[1] [2]"

- ↑ The picture labeled "Human Chromosome 2 and its analogs in the apes" in the article Comparison of the Human and Great Ape Chromosomes as Evidence for Common Ancestry is literally a picture of a link in humans that links two separate chromosomes in the nonhuman apes creating a single chromosome in humans. It is considered a missing link, and the ape-human connection is of particular interest. Also, while the term originally referred to fossil evidence, this too is a trace from the past corresponding to some living beings which when alive were the physical embodiment of this link.

- ↑ The New York Times report Still Evolving, Human Genes Tell New Story, based on A Map of Recent Positive Selection in the Human Genome, states the International HapMap Project is "providing the strongest evidence yet that humans are still evolving" and details some of that evidence.

- ↑ Pseudogene evolution and natural selection for a compact genome. "[3]"

- ↑ Okamoto N, Inouye I. (2005). A secondary symbiosis in progress. Science 310 (5746): 287.

- ↑ Okamoto N, Inouye I. (2006). Hatena arenicola gen. et sp. nov., a Katablepharid Undergoing Probable Plastid Acquisition.. Protist Article in Print.

- ↑ Feder et al (2003). Evidence for inversion polymorphism related to sympatric host race formation in the apple maggot fly, Rhagoletis pomonella.. Genetics 163 (3): 939-953.

- ↑ Berlocher, S.H. and G.L. Bush. 1982. An electrophoretic analysis of Rhagoletis (Diptera: Tephritidae) phylogeny. Systematic Zoology 31:136-155; Berlocher, S.H. and J.L. Feder. 2002. Sympatric speciation in phytophagous insects: moving beyond controversy? Annual Review of Entomology 47:773-815; Bush, G.L. 1969. Sympatric host race formation and speciation in frugivorous flies of the genus Rhagoletis (Diptera: Tephritidae). Evolution 23:237-251; Prokopy, R.J., S.R. Diehl and S.S. Cooley. 1988. Behavioral evidence for host races in Rhagoletis pomonella flies. Oecologia 76:138-147. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA - Vol. 94, pp. 11417-11421, October 1997 - Evolution article Selective maintenance of allozyme differences among sympatric host races of the apple maggot fly.

- Darwin, Charles November 24 1859. On the Origin of Species by means of Natural Selection or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life. London: John Murray, Albemarle Street. 502 pages. Reprinted: Gramercy (May 22, 1995). ISBN 0-517-12320-7