Jaguar

| Jaguar[1] | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

A jaguar at the Milwaukee County Zoological Gardens

| ||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| Panthera onca Linnaeus, 1758 | ||||||||||||||

Jaguar range

|

The jaguar (Panthera onca) is a New World mammal of the Felidae family and one of four "big cats" in the Panthera genus, along with the tiger, lion, and leopard of the Old World. The jaguar is the third-largest feline after the tiger and the lion, and on average the largest and most powerful feline in the Western Hemisphere. The jaguar is the only New World member of the Panthera genus.

The jaguar's present range extends from Mexico (with occasional sightings in the southwestern United States) across much of Central America and south to Paraguay and northern Argentina.

The jaguar is a largely solitary, stalk-and-ambush predator, and is opportunistic in prey selection. It is also an apex predator, at the top of the food chain, and is a keystone predator, having a disproportionate effect on its environment relative to its abundance. The jaguar has developed an exceptionally powerful bite, even relative to the other big cats (Wroe et al. 2006). This allows it to pierce the shells of armored reptiles and to employ an unusual killing method: it bites directly through the skull of prey between the ears to deliver a fatal blow to the brain (Hamdig 2006).

The jaguar also is a threat to livestock, and for such a reason their value has often been misunderstood. Hunted and killed by ranchers concerned about their cattle, loss of habitat due to human settlement, and competition for food with human beings are some of the anthropogenic causes that have resulted in their numbers declining to the point that they are considered "near threatened." In some countries, their populations have become extinct. But like other animals, jaguars provide a value to the ecosystem and to humans. The jaguar plays an important role in stabilizing ecosystems and regulating the populations of prey species. For humans, jaguars add to the wonder of nature, and are popular attractions both in the wild, where their sighting can offer a memorable experience, and in captivity, such as in zoos. For the early cultures in Central and South America, they were a symbol of power, strength, and mystery, and played an important role in culture and mythology.

This spotted cat most closely resembles the leopard physically, although it is of sturdier build and its behavioral and habitat characteristics are closer to those of the tiger. While dense jungle is its preferred habitat, the jaguar will range across a variety of forested and open terrain. It is strongly associated with the presence of water and is notable, along with the tiger, as a feline that enjoys swimming.

Biology and behavior

Physical characteristics

The jaguar is a compact and well-muscled animal. There are significant variations in size: weights are normally in the range of 56â96 kilograms (124â211 lbs). Larger jaguars have been recorded as weighing 131â151 kilograms (288â333 lbs) (matching the average for lion and tiger females), and smaller ones have extremely low weights of 36 kilograms (80 lbs). Females are typically 10â20 percent smaller than males. The length of the cat varies from 1.62â1.83 meters (5.3â6 feet), and its tail may add a further 75 centimeters (30 in). It stands about 67â76 centimeters (27â30 in) tall at the shoulders.

Further variations in size have been observed across regions and habitats, with size tending to increase from the north to south. A study of the jaguar in the Chamela-Cuixmala Biosphere Reserve on the Mexican Pacific coast, showed ranges of just 30â50 kilograms (66â110 lbs), about the size of the cougar (Nuanaez et al. 2000). By contrast, a study of the jaguar in the Brazilian Pantanal region found average weights of 100 kilograms (220 lbs). Forest jaguars are frequently darker and considerably smaller than those found in open areas (the Pantanal is an open wetland basin), possibly due to the fewer large herbivorous prey in forest areas (Nowell and Jackson 1996).

A short and stocky limb structure makes the jaguar adept at climbing, crawling, and swimming. The head is robust and the jaw extremely powerful. It has been suggested that the jaguar has the strongest bite of all felids, and the second strongest of all mammals; this strength is an adaptation that allows the jaguar to pierce turtle shells (Hamdig 2006). It has been reported that "an individual jaguar can drag a 360 kg (800-pound) bull 25 feet (8 m) in its jaws and pulverize the heaviest bones" (McGrath 2004). The jaguar hunts wild animals weighing up to 300 kilograms (660 lb) in dense jungle, and its short and sturdy physique is thus an adaptation to its prey and environment.

The base coat of the jaguar is generally a tawny yellow, but can range to reddish-brown and black. The cat is covered in rosettes (rose-like markings or formation, which is found in clusters and patches on the fur) for camouflage in its jungle habitat. The spots vary over individual coats and between individual jaguars: rosettes may include one or several dots, and the shape of the dots varies. The spots on the head and neck are generally solid, as are those on the tail, where they may merge to form a band. The underbelly, throat, and outer surface of the legs and lower flanks are white.

A condition known as melanism (increased amount of black or nearly black pigmentation) occurs in the species. The melanistic form is less common than the spotted formâsix percent of jaguars in their South American range have been reported to possess it (Dinets 2006)âand is the result of a dominant allele (Meyer 1994). Jaguars with melanism appear entirely black, although their spots are still visible on close examination. Melanistic jaguars are informally known as black panthers, but do not form a separate species. Rare albino individuals, sometimes called white panthers, occur among jaguars, as with the other big cats (Nowell and Jackson 1996).

The jaguar closely resembles the leopard, but is sturdier and heavier, and the two animals can be distinguished by their rosettes: the rosettes on a jaguar's coat are larger, fewer in number, usually darker, and have thicker lines and small spots in the middle that the leopard lacks. Jaguars also have rounder heads and shorter, stockier limbs compared to leopards.

Reproduction and life cycle

Jaguar females reach sexual maturity at about two years of age, and males at three or four. The cat is believed to mate throughout the year in the wild, although births may increase when prey is plentiful (Spindler and Johnson n.d.). Research on captive male jaguars supports the year-round mating hypothesis, with no seasonal variation in semen traits and ejaculatory quality; low reproductive success has also been observed in captivity (Morato et al. 1999). Female estrous is 6â17 days out of a full 37-day cycle, and females will advertise fertility with urinary scent marks and increased vocalization (Spindler and Johnson 2005).

Mating pairs separate after the act, and females provide all parenting. The gestation period lasts 93â105 days; females give birth to up to four cubs, and most commonly to two. The mother will not tolerate the presence of males after the birth of cubs, given a risk of infant cannibalism; this behavior is also found in the tiger (Baker et al. 2005).

The young are born blind, gaining sight after two weeks. Cubs are weaned at three months but remain in the birth den for six months before leaving to accompany their mother on hunts. They will continue in their mother's company for one to two years before leaving to establish a territory for themselves. Young males are at first nomadic, jostling with their older counterparts until they succeed in claiming a territory. Typical lifespan in the wild is estimated at around 12â15 years; in captivity, the jaguar lives up to 23 years, placing it among the longest-lived cats.

Social structure

Like most cats, the jaguar is solitary outside mother-cub groups. Adults generally meet only to court and mate (though limited non-courting socialization has been observed anecdotally) (Baker et al. 2005) and carve out large territories for themselves. Female territories, from 25 to 40 square kilometers in size, may overlap, but the animals generally avoid one another. Male ranges cover roughly twice as much area, varying in size with the availability of game and space, and do not overlap (Baker et al. 2005; Schaller and Grandsen 1980). Scrape marks, urine, and feces are used to mark territory (Rabinowitz and Nottingham 1986).

Like the other big cats, the jaguar is capable of roaring (the male more powerfully) and does so to warn territorial and mating competitors away; intensive bouts of counter-calling between individuals have been observed in the wild (Emmons 1987). Their roar often resembles a repetitive cough, and they may also vocalize mews and grunts. Mating fights between males occur, but are rare, and aggression avoidance behavior has been observed in the wild (Rabinowitz and Nottingham, 1986). When it occurs, conflict is typically over territory: a male's range may encompass that of two or three females, and he will not tolerate intrusions by other adult males (Baker et al. 2005).

The jaguar is often described as nocturnal, but is more specifically crepuscular (peak activity around dawn and dusk). Both sexes hunt, but males travel further each day than females, befitting their larger territories. The jaguar may hunt during the day if game is available and is a relatively energetic feline, spending as much as 50â60 percent of its time active (Nowell and Jackson 1996). The jaguar's elusive nature and the inaccessibility of much of its preferred habitat make it a difficult animal to sight, let alone study.

Hunting and diet

Like all cats, the jaguar is an obligate carnivore, feeding only on meat. It is an opportunistic hunter and its diet encompasses at least 85 species (Nowell and Jackson 1996). The jaguar prefers large prey and will take deer, tapirs, peccaries, dogs, and even anacondas and caiman. However, the cat will eat any small species that can be caught, including frogs, mice, birds, fish, sloths, monkeys, turtles, capybara, and domestic livestock.

While the jaguar employs the deep-throat bite-and-suffocation technique typical among Panthera, it prefers a killing method unique amongst cats: it pierces directly through the temporal bones of the skull between the ears of prey (especially the capybara) with its canine teeth, piercing the brain. This may be an adaptation to "cracking open" turtle shells; following the late Pleistocene extinctions, armored reptiles such as turtles would have formed an abundant prey base for the jaguar (Emmons 1987; Nowell and Jackson 1996). The skull bite is employed with mammals in particular; with reptiles such as the caiman, the jaguar may leap on to the back of the prey and sever the cervical vertebrae, immobilizing the target. While capable of cracking turtle shells, the jaguar may simply reach into the shell and scoop out the flesh (Baker 2005). With prey such as dogs, a paw swipe to crush the skull may be sufficient.

The jaguar is a stalk-and-ambush rather than a chase predator. The cat will walk slowly down forest paths, listening for and stalking prey before rushing or ambushing. The jaguar attacks from cover and usually from a target's blind spot with a quick pounce; the species' ambushing abilities are considered nearly peerless in the animal kingdom by both indigenous people and field researchers, and are probably a product of its role as an apex predator in several different environments. The ambush may include leaping into water after prey, as a jaguar is quite capable of carrying a large kill while swimming; its strength is such that carcasses as large as a heifer can be hauled up a tree to avoid flood levels (Baker et al. 2005).

On killing prey, the jaguar will drag the carcass to a thicket or other secluded spot. It begins eating at the neck and chest, rather than the midsection. The heart and lungs are consumed, followed by the shoulders (Baker et al. 2005). The daily food requirement of a 34-kilogram animal, at the extreme low end of the species' weight range, has been estimated at 1.4 kilograms. For captive animals in the 50â60 kilogram range, more than 2 kilograms of meat daily is recommended (Ward and Hunt 2005). In the wild, consumption is naturally more erratic; wild cats expend considerable energy in the capture and kill of prey, and may consume up to 25 kilograms of meat at one feeding, followed by periods of famine (Ward and Hunt 2005).

Etymology

The first component of its scientific designation, Panthera onca, is often presumed to derive from Greek pan- ("all") and ther ("beast"), but this may be a folk etymology. Although it came into English through the classical languages, panthera is probably of East Asian origin, meaning "the yellowish animal," or "whitish-yellow."

Onca is said to denote "barb" or "hook," a reference to the animal's powerful claws, but the most correct etymology is simply that it is an adaptation of the current Portuguese name for the animal, onça (on-sa), with the cedilla dropped for typographical reasons.

The etymology of the word jaguar is unclear. Some sources suggest a borrowing from the South American Tupi language to English via Portuguese, while others attribute the term to the related Guaranà languages. In the Tupi language, the original and complete indigenous name for the species is jaguara, which has been reported as a denotation for any carnivorous animalâin the compound form jaguareté, -eté means "true." In the related Guaranà languages, yaguareté has been variously translated as "the real fierce beast," "dog-bodied," or "fierce dog" (Diaz 1890).

Early etymological reports were that jaguara means "a beast that kills its prey with one bound," and this claim persists in a number of sources. However, this has been challenged as incorrect. In many Central and South American countries, the cat is referred to as el tigre ("the tiger").

Taxonomy

DNA evidence shows that the lion, the tiger, the leopard, the jaguar, the snow leopard, and the clouded leopard share a common ancestor and that this group is between six and ten million years old (Johnson et al. 2006). However, the fossil record points to the emergence of Panthera just two to 3.8 million years ago (Johnson et al. 2006; Turner 1987).

The clouded leopard (Neofelis nebulosa) is generally placed at the basis of this group (Johnson et al. 2006; Yu and Zhang 2005; Johnson and O'Brien 1997; Janczewski et al. 1996). The position of the remaining species varies between studies and is effectively unresolved. Many studies place the snow leopard within the genus Panthera (Johnson et al. 2006; Yu and Zhang 2005; Janczewski et al. 1996) but there is no consensus whether the scientific name of the snow leopard should remain Uncia uncia (Shoemaker 1996) or be moved to Panthera uncia (Johnson et al. 2006; Yu and Zhang 2005; Johnson and O'Brien 1997; Janczewski et al. 1996).

The jaguar has been attested in the fossil record for two million years and it has been an American cat since crossing the Bering Land Bridge during the Pleistocene; the immediate ancestor of modern animals is Panthera onca augusta, which was larger than the contemporary cat (Ruiz-Garcia et al. 2006).

Based on morphological evidence, British zoologist Reginald Pocock concluded that the jaguar is most closely related to the leopard (Janczewski et al. 1996). However, DNA evidence is inconclusive and the position of the jaguar relative to the other species varies between studies (Johnson et al. 2006; Yu and Zhang, 2005; Johnson and O'Brien, 1997; Janczewski et al. 1996). Fossils of extinct Panthera species, such as the European jaguar (Panthera gombaszoegensis) and the American lion (Panthera atrox), show characteristics of both the lion and the jaguar (Janczewski et al. 1996). Analysis of jaguar mitochondrial DNA has dated the species lineage to between 280,000 and 510,000 years ago, later than suggested by fossil records (Eizirik et al. 2001).

Geographical variation

The last taxonomic delineation of the jaguar subspecies was performed by Pocock in 1939. Based on geographic origins and skull morphology, he recognized 8 subspecies. However, he did not have access to sufficient specimens to critically evaluate all subspecies, and he expressed doubt about the status of several. Later consideration of his work suggested only 3 subspecies should be recognized (Seymore 1989).

Recent studies have also failed to find evidence for well-defined subspecies and are no longer recognized (Nowak 1999). Larson (1997) studied the morphological variation in the jaguar and showed that there is clinal northâsouth variation, but also that the differentiation within the supposed subspecies is larger than that between them and thus does not warrant subspecies subdivision (Larson 1997). A genetic study by Eizirik and coworkers in 2001 confirmed the absence of a clear geographical subspecies structure, although they found that major geographical barriers such as the Amazon River limited the exchange of genes between the different populations (Eirzirik 2001; Ruiz-Garcia et al. 2006).

Pocock's subspecies divisions are still regularly listed in general descriptions of the cat (Johnson 2005). Seymore grouped these in three subspecies (Seymore 1989).

- Panthera onca onca: Venezuela, south and east to Rio Grande do Sul in Brazil, including

- P. onca peruviana: Coastal PeruâPeruvian jaguar

- P. onca hernandesii: Western MexicoâMexican jaguar

- P. onca palustris or P. onca paraguensis: Paraguay and northeastern Argentina (Seymore 1989).

The canonical Mammal Species of the World continues to recognize nine sub-species: P. o. onca, P. o. arizonensis, P. o. centralis, P. o. goldmani, P. o. hernandesii, P. o. palustris, P. o. paraguensis, P. o. peruviana, and P. o. veraecruscis (Wozencraft 2005).

Ecology

Distribution and habitat

The jaguar's present range extends from Mexico, through Central America and into South America, including much of Amazonian Brazil (Sanderson et al. 2005). The countries included in its range are Argentina, Belize, Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, French Guiana, Guatemala, Guyana, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Suriname, United States, and Venezuela. The jaguar is now extinct in El Salvador and Uruguay (Nowell et al. 2002). The largest protected jaguar habitat is the 400 square kilometer Cockscomb Basin Wildlife Sanctuary in Belize.

The inclusion of the United States in the list is based on occasional sightings in the southwest, particularly in Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas. In the early 1900s, the jaguar's range extended as far north as Southern California and western Texas. The jaguar is a protected species in the United States under the Endangered Species Act, which has stopped the shooting of the animal for its pelt. In 2004, wildlife officials in Arizona photographed and documented jaguars in the south of the state. For any permanent population to thrive in Arizona, protection from killing, an adequate prey base, and connectivity with Mexican populations are essential.

The historic range of the species included much of the southern half of the United States, and in the south extended much farther to cover most of the South American continent. In total, its northern range has receded 1,000 kilometers southward and its southern range 2,000 kilometers northward. Ice Age fossils of the jaguar, dated between 40,000 and 11,500 kya, have been discovered in the United States, including some at an important site as far north as Missouri. Fossil evidence shows jaguars of up to 190 kilograms (420 lbs), much larger than the contemporary average for the animal.

The habitat of the cat includes the rainforests of South and Central America, open, seasonally flooded wetlands, and dry grassland terrain. Of these habitats, the jaguar much prefers dense forest (Nowell and Jackson 1996); the cat has lost range most rapidly in regions of drier habitat, such as the Argentinean Pampas, the arid grasslands of Mexico, and the southwestern United States (Nowell et al. 2002). The cat will range across tropical, subtropical, and dry deciduous forests (including, historically, oak forests in the United States). The jaguar is strongly associated with water and it often prefers to live by rivers, swamps, and in dense rainforest with thick cover for stalking prey. Jaguars have been found at elevations as high as 3,800 m, but they typically avoid mountain forest and are not found in the high plateau of central Mexico or in the Andes (Nowell and Jackson 1996).

Ecological role

The jaguar is an apex predator, meaning that it exists at the top of its food chain and is not regularly preyed on in the wild. The jaguar has also been termed a keystone species, as it is assumed, through controlling the population levels of prey such as herbivorous and granivorous mammals, apex felids maintain the structural integrity of forest systems (Nuanaez et al. 2000). However, accurately determining what effect species like the jaguar have on ecosystems is difficult, because data must be compared from regions where the species is absent as well as its current habitats, while controlling for the effects of human activity. It is accepted that mid-sized prey species see population increases in the absence of the keystone predators and it has been hypothesized that this has cascading negative effects (Butler 2006); however, field work has shown this may be natural variability and that the population increases may not be sustained. Thus, the keystone predator hypothesis is not favored by all scientists (Wright et al. 1994).

The jaguar also has an effect on other predators. The jaguar and the cougar, the next largest feline of the Americas, are often sympatric (related species sharing overlapping territory) and have often been studied in conjunction. Where sympatric with the jaguar, the cougar is smaller than normal. The jaguar tends to take larger prey and the cougar smaller, reducing the latter's size (Iriarte et al. 1990). This situation may be advantageous to the cougar. Its broader prey niche, including its ability to take smaller prey, may give it an advantage over the jaguar in human-altered landscapes (Nuanaez et al. 2000); while both are classified as near-threatened species, the cougar has a significantly larger current distribution.

In mythology and culture

In Central and South America, the jaguar has long been a symbol of power and strength. By 900 B.C.E., the ChavÃn cult of the jaguar became accepted over most of what is today Peru. Concurrent with ChavÃn, the Olmec, the progenitor culture of Pre-Columbian Mesoamerica, developed a distinct "were-jaguar" motif of sculptures and figurines showing stylized jaguars or humans with jaguar characteristics.

In the later Maya civilization, the jaguar was believed to facilitate communication between the living and the dead and to protect the royal household. The Maya saw these powerful felines as their companions in the spiritual world, and kings were typically given a royal name incorporating the word jaguar.

The Aztec civilization shared this image of the jaguar as the representative of the ruler and as a warrior. The Aztecs formed an elite warrior class known as the Jaguar Knights. In Aztec mythology, the jaguar was considered to be the totem animal of the powerful deity Tezcatlipoca.

Conservation status

Given the inaccessibility of much of the species' rangeâparticularly the central Amazonâestimating jaguar numbers is difficult. Researchers typically focus on particular bioregions, and thus species-wide analysis is scant. In 1991, 600â1,000 (the highest total) were estimated to be living in Belize. A year earlier, 125â180 jaguars were estimated to be living in Mexico's 4,000 square kilometer (2400 mi²) Calakmul Biosphere Reserve, with another 350 in the state of Chiapas. The adjoining Maya Biosphere Reserve in Guatemala, with an area measuring 15,000 square kilometers (9,000 mi²), may have 465â550 animals (Johnson 2005). Work employing GPS-telemetry in 2003 and 2004 found densities of only six to seven jaguars per 100 square kilometers in the critical Pantanal region, compared with 10 to 11 using traditional methods; this suggests that widely used sampling methods may inflate the actual numbers of cats (Soisalo and Cavalcanti 2006).

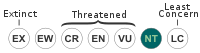

The jaguar is considered near-threatened by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (Nowell et al. 2002), meaning it may be threatened with extinction in the near future. The loss of parts of its range, including its virtual elimination from its historic northern areas and the increasing fragmentation of the remaining range, has contributed to this status.

Jaguar populations are currently declining. Detailed work performed under the auspices of the Wildlife Conservation Society reveal that the animal has lost 37 percent of its historic range, with its status unknown in an additional 18 percent. More encouragingly, the probability of long-term survival was considered high in 70 percent of its remaining range, particularly in the Amazon basin and the adjoining Gran Chaco and Pantanal (Sanderson et al. 2002).

The major risks to the jaguar include deforestation across its habitat, increasing competition for food with human beings (Nowell et al. 2002), and the behavior of ranchers who will often kill the cat where it preys on livestock. When adapted to the prey, the jaguar has been shown to take cattle as a large portion of its diet. While land clearance for grazing is a problem for the species, the jaguar population may have increased when cattle were first introduced to South America as the animals took advantage of the new prey base. This willingness to take livestock has induced ranch owners to hire full-time jaguar hunters, and the cat is often shot on sight.

The jaguar is regulated as an Appendix I species under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES): all international trade in jaguars or their parts is prohibited. All hunting of jaguars is prohibited in Argentina, Belize, Colombia, French Guiana, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Suriname, the United States, Uruguay, and Venezuela. Hunting of jaguars is restricted to "problem animals" in Brazil, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Mexico, and Peru, while trophy hunting is still permitted in Bolivia. The species has no legal protection in Ecuador or Guyana.

Current conservation efforts often focus on educating ranch owners and promoting ecotourism. The jaguar is generally defined as an "umbrella species"âa species whose home range and habitat requirements are sufficiently broad that, if protected, numerous other species of smaller range will also be protected. Umbrella species serve as "mobile links" at the landscape scale, in the jaguar's case through predation. Conservation organizations may thus focus on providing viable, connected habitat for the jaguar, with the knowledge that other species will also benefit.

Notes

- â W. C. Wozencraft, âOrder Carnivora,â in Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference, ed. D. E. Wilson and D. M. Reeder (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1992 ISBN 0801882214), 546â547.

- â K. Nowell, U. Breitenmoser, C. Breitenmoser, and P. Jackson, Panthera onca, 2006 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (IUCN, 2006). Retrieved December 13, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

All links retrieved December 13, 2007.

- Akron Zoo. 2006. Jaguar (Panthera onca).

- Arizona Game and Fish. 2006. Jaguar Management.

- Baker, W., S. Deem, A. Hunt, L. Munson, S. Johnson, R. Spindler, and A. Ward. 2005. Guidelines for Captive Management of Jaguars. Jaguar SSP Management Group.

- Butler, R. 2006. Structure and Character: Keystone Species. Mongabay.com.

- Defenders of Wildlife. 2007. Jaguar.

- Diaz, E. A. 1890. Nativa. Wikisource.

- Dinets, V., and P. Polechla. 2006. First documentation of melanism in the jaguar (Panthera onca) from northern Mexico. Vladimir Dinets Homepage.

- Eggerton, J. 2006. Jaguars: Magnificence in the Southwest. Wild Tracks, Spring 2006.

- Emmons, L. 1987. Comparative feeding ecology of felids in a neotropical rainforest. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 20(4): 271.

- Faculty of Law, University of Buenos Aires. 2006. Breve vocabulario (in Spanish).

- Hamdig, P. 2006. National animal: jaguar. RBC Radio.

- Illinois State Museum. 2006. Jaguars. Exhibit on The Midwestern United States 16,000 years ago.

- Institute for Etymological Research and Education. 2006. Word to the wise. Take our Word for It 198: 2.

- Iriarte, J. A., W. L. Franklin, W. E. Johnson, and K. H. Redford. 1990. Biogeographic variation of food habits and body size of the American Puma. Oecologia 85(2): 185.

- Janczewski, D. N., W. S. Modi, J. C. Stephens, and S. J. O'Brien. 1996. Molecular evolution of mitochondrial 12S RNA and cytochrome b sequences in the pantherine lineage of felidae. Molecular Biology and Evolution 12(4):690.

- Johnson, S. 2005. Description, distribution, status and taxonomy. In Guidelines for Captive Management of Jaguars, ed. W. K. Baker, et al., 3â7. Jaguar SSP Management Group.

- Johnson, W. E., E. Eizirik, J. Pecon-Slattery, W. K. Murphy, A. Antunes, E. Teeling, and S. J. O'Brien. 2006. The Late Miocene radiation of modern Felidae: A genetic assessment. Science 311: 73â77.

- Johnson, W. E., and S. J. O'Brien. 1997. Phylogenetic reconstruction of the Felidae using 16S rRNA and NADH-5 mitochondrial genes. Journal of Molecular Evolution 44: S98-S116.

- Larson, S. E. 1997. Taxonomic re-evaluation of the jaguar. Zoo Biology 16(2): 107.

- McGrath, S. 2004. Top cat. National Audubon Society.

- Meyer, J. R. 1994. Black Jaguars in Belize?: A survey of melanism in the jaguar, Panthera onca. Belize Explorer Group.

- Morato, R. G., M. A. Barros de Vaz Guimaraes, F. Ferriera, I. Terezhina do Nascimento Verreschi, and R. Capmanarut Barnabe. 1999. Reproductive characteristics of captive male jaguars. Brazilian Journal of Veterinary Research and Animal Science 36(5).

- Nowak, R. M. 1999. Walker's Mammals of the World, 6th ed. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0801857899.

- Nowell, K., U. Breitenmoser, C. Breitenmoser, and P. Jackson. 2002. Panthera onca. 2006 UCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN.

- Nowell, K., and P. Jackson, (comps. and eds.). 1996. Wild Cats, Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group.

- Nuanaez, R., B. Miller, and F. Lindzey. 2000. Food habits of the jaguars and pumas in Jalisco, Mexico. Journal of Zoology 252(3): 373.

- Online Etymology Dictionary. 2007. Panther. Etymonline.com.

- Phoenix Zoo. 2006. Jaguar (Panthera onca).

- Pima County Government. 2006. Glossary. Pima County Zoo.

- RED Yaguaretè. 2006. Yaguaretè - La Verdadera Fiera (in Spanish).

- Rabinowitz, A. R., and B. G. Notingham. 1986. Ecology and behavior of the jaguar (Panthera onca) in Belize, Central America. Journal of Zoology 210(1): 149.

- Ruiz-Garcia, M., E. Payan, A. Murillo, and D. Alvarez. 2006. DNA microsatellite characterization of the jaguar (Panthera onca) in Colombia. Genes & Genetic Systems 81(2): 115â127.

- Sanderson, E. W., K. H. Redford, C. B. Chetkiewicz, R. A. Medellin, A. R. Rabinowitz, J. G. Robinson, and A. B. Taber. 2002. Planning to save a species: the jaguar as a model. Conservation Biology 16(1): 58.

- Schaller, G. B., and P. G. Crawshaw. 1980. Movement patterns of jaguar. Biotropica 12(3): 161.

- Seymore, K. L. 1989. Panthera onca. Mammalian Species 340: 1â9.

- Shoemaker, A. H. 1996. Taxanomic and legal status of the felida. Felid Taxon Advisory Group.

- Soisalo, M. K., and S. M. C. Cavalcanti. 2006. Estimating the density of the jaguar population in the Brazilian Pantanal using camera-traps and capture-recapture sampling in combination with GPS radio-telemetry. Biological Conservation 129: 487.

- Spindler, R., and S. Johnson. 2005. Management of reproduction. In Guidelines for Captive Management of Jaguars, ed. W. K. Baker, et al., 28â37. Jaguar SSP Management Group.

- Turner, A. 1987. New fossil carnivore remains from the Sterkfontien hominid site. Ann Transvall Mus 34: 319â347.

- Ward, A. M, and A. Hunt. 2005. Hand-rearing. In Guidelines for Captive Management of Jaguars, ed. W. K. Baker, et al., 62â74. Jaguar SSP Management Group.

- Wildlife Conservation Society, n.d. All about jaguars: Ecology. Save the Jaguar.

- World Wildlife Fund (WWF). 2006. Jaguar refuge in the Llanos ecoregion.

- Wozencraft, W. C. 2005. Carnivora. In Mammal Species of the World, 3rd ed., ed. D. E. Wilson and D. M. Reeder. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0801882214.

- Wright, S. J., M. E. Gomper, and B. DeLeon. 1994. Are large predators keystone species in Neotropical forests? The evidence from Barro Colorado Island. Oikos 71(2): 279.

- Wroe, S., C. McHenry, and J. Thomason. 2006. Bite club: Comparative bite force in big biting mammals and prediction of predatory behavior in fossil taxa. Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

- Yu, L., and Y. P. Zhang. 2005. Phylogenetic studies of pantherine cats (Felidae) based on multiple genes, with novel application of nuclear beta-fibrinogen intron 7 to carnvivores. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 35(2): 483â495.

External links

All links retrieved December 17, 2024.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.