Decolonization

Decolonization refers to the undoing of colonialism, the establishment of governance or authority through the creation of settlements by another country or jurisdiction. The term generally refers to the achievement of independence by the various Western colonies and protectorates in Asia and Africa following World War II. This conforms with an intellectual movement known as Post-Colonialism. A particularly active period of decolonization occurred between 1945 to 1960, beginning with the independence of Pakistan and the Republic of India from Great Britain in 1947 and the First Indochina War. A number of national liberation movements were established prior to the war, but most did not achieve their aims until after it. Decolonization can be achieved by attaining independence, integrating with the administering power or another state, or establishing a "free association" status. The United Nations has stated that in the process of decolonization there is no alternative to the principle of self-determination. Decolonization may involve peaceful negotiation and/or violent revolt and armed struggle by the native population.

Methods and stages

Decolonization is a political process, frequently involving violence. In extreme circumstances, there is a war of independence, sometimes following a revolution. More often, there is a dynamic cycle where negotiations fail, minor disturbances ensue resulting in suppression by the police and military forces, escalating into more violent revolts that lead to further negotiations until independence is granted. In rare cases, the actions of the native population are characterized by non-violence, India being an example of this, and the violence comes as active suppression from the occupying forces or as political opposition from forces representing minority local communities who feel threatened by the prospect of independence. For example, there was a war of independence in French Indochina, while in some countries in French West Africa (excluding the Maghreb countries) decolonization resulted from a combination of insurrection and negotiation. The process is only complete when the de facto government of the newly independent country is recognized as the de jure sovereign state by the community of nations.

Independence is often difficult to achieve without the encouragement and practical support from one or more external parties. The motives for giving such aid are varied: nations of the same ethnic and/or religious stock may sympathize with oppressed groups, or a strong nation may attempt to destabilize a colony as a tactical move to weaken a rival or enemy colonizing power or to create space for its own sphere of influence; examples of this include British support of the Haitian Revolution against France, and the Monroe Doctrine of 1823, in which the United States warned the European powers not to interfere in the affairs of the newly independent states of the Western Hemisphere.

As world opinion became more pro-emancipation following World War I, there was an institutionalized collective effort to advance the cause of emancipation through the League of Nations. Under Article 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations, a number of mandates were created. The expressed intention was to prepare these countries for self-government, but the reality was merely a redistribution of control over the former colonies of the defeated powers, mainly Germany and the Ottoman Empire. This reassignment work continued through the United Nations, with a similar system of trust territories created to adjust control over both former colonies and mandated territories administered by the nations defeated in World War II, including Japan.

In referendums, some colonized populations have chosen to retain their colonial status, such as Gibraltar and French Guiana. On the other hand, colonial powers have sometimes promoted decolonization in order to shed the financial, military and other burdens that tend to grow in those colonies where the colonial regimes have become more benign.

Empires have expanded and contracted throughout history but, in several respects, the modern phenomenon of decolonization has produced different outcomes. Now, when states surrender both the de facto rule of their colonies and their de jure claims to such rule, the ex-colonies are generally not absorbed by other powers. Further, the former colonial powers have, in most cases, not only continued existing, but have also maintained their status as Powers, retaining strong economic and cultural ties with their former colonies. Through these ties, former colonial powers have ironically maintained a significant proportion of the previous benefits of their empires, but with smaller costs — thus, despite frequent resistance to demands for decolonisation, the outcomes have satisfied the colonizers' self-interests. [citation needed]

Decolonization is rarely achieved through a single historical act, but rather progresses through one or more stages of emancipation, each of which can be offered or fought for: these can include the introduction of elected representatives (advisory or voting; minority or majority or even exclusive), degrees of autonomy or self-rule. Thus, the final phase of decolonisation may in fact concern little more than handing over responsibility for foreign relations and security, and soliciting de jure recognition for the new sovereignty. But, even following the recognition of statehood, a degree of continuity can be maintained through bilateral treaties between now equal governments involving practicalities such as military training, mutual protection pacts, or even a garrison and/or military bases.

There is some debate over whether or not the United States, Canada and Latin America can be considered decolonized, as it was the colonist and their descendants who revolted and declared their independence instead of the indigenous peoples, as is usually the case. Scholars such as Elizabeth Cook-Lynn (Dakota) and Devon Mihesuah (Choctaw) have argued that portions of the United States still are in need of decolonisation[citation needed].

Decolonization in a broad sense

Stretching the notion further, internal decolonization can occur within a sovereign state. Thus, the expansive United States created territories, destined to colonize conquered lands bordering the existing states, and once their development proved successful (often involving new geographical splits) allowed them to petition statehood within the federation, granting not external independence but internal equality as 'sovereign' constituent members of the federal Union. France internalized several overseas possessions as Départements d'outre-mer.

Even in a state which legally does not colonize any of its 'integral' parts, real inequality often causes the politically dominant component - often the largest and/or most populous part (such as Russia within the formally federal USSR as earlier in the czar's empire),[citation needed] or the historical conqueror (such as Austria, the homelands of the ruling Habsburg dynasty, within an empire of mainly Slavonic 'minorities' from Silesia to the shifting Ottoman border)[citation needed] - to be perceived, at least subjectively, as a colonizer in all but name; hence, the dismemberment of such a 'prison of peoples' is perceived as decolonisation de facto.[citation needed]

To complicate matters even further, this may coincide with another element. Thus, the three Baltic republics - Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania - argue that they, in contrast with other constituent SSRs, could not have been granted independence at the dismemberment of the Soviet Union because they never joined, but were militarily annexed by Stalin, and thus had been illegally colonized, including massive deportations of their nationals and uninvited immigration of ethnic Russians and other soviet nationalities.[citation needed] Even in other post-Soviet states which had formally acceded, most ethnic Russians were so much identified with the Soviet 'colonization,' they felt unwelcome and migrated back to Russia.[citation needed]

Amongst the countries which are likely to decolonise territories over the next two decades are the U.K. (Bermuda, Gibraltar, Sovereign Bases in Cyprus, British Virgin Islands, Falklands, etc), U.S.A. (U.S. Virgin Islands, American Samoa, Guam, etc), and France (French Guiana, French Polynesia, New Caledonia, Reunion, Guadalope, etc).

Decolonization before 1918

....

Decolonization after 1918

Western European colonial powers

The New Imperialism period, with the scramble for Africa and the Opium Wars, marked the zenith of European colonization. It also marked the acceleration of the trends that would end it. The extraordinary material demands of the conflict had spread economic change across the world (notably inflation), and the associated social pressures of "war imperialism" created both peasant unrest and a burgeoning middle class.

Economic growth created stakeholders with their own demands, while racial issues meant these people clearly stood apart from the colonial middle-class and had to form their own group. The start of mass nationalism, as a concept and practice, would fatally undermine the ideologies of imperialism.

There were, naturally, other factors, from agrarian change (and disaster – French Indochina), changes or developments in religion (Buddhism in Burma, Islam in the Dutch East Indies, marginally people like John Chilembwe in Nyasaland), and the impact of the depression of the 1930s.

The Great Depression, despite the concentration of its impact on the industrialized world, was also exceptionally damaging in the rural colonies. Agricultural prices fell much harder and faster than those of industrial goods. From around 1925 until World War II, the colonies suffered. The colonial powers concentrated on domestic issues, protectionism and tariffs, disregarding the damage done to international trade flows. The colonies, almost all primary "cash crop" producers, lost the majority of their export income and were forced away from the "open" complementary colonial economies to "closed" systems. While some areas returned to subsistence farming (British Malaya) others diversified (India, West Africa), and some began to industrialise. These economies would not fit the colonial strait-jacket when efforts were made to renew the links. Further, the European-owned and -run plantations proved more vulnerable to extended deflation than native capitalists, reducing the dominance of "white" farmers in colonial economies and making the European governments and investors of the 1930s co-opt indigenous elites — despite the implications for the future.

The efforts at colonial reform also hastened their end — notably the move from non-interventionist collaborative systems towards directed, disruptive, direct management to drive economic change. The creation of genuine bureaucratic government boosted the formation of indigenous bourgeoisie. This was especially true in the British Empire, which seemed less capable (or less ruthless) in controlling political nationalism. Driven by pragmatic demands of budgets and manpower the British made deals with the nationalist elites. They dealt with the white Dominions, retained strategic resources at the cost of reducing direct control in Egypt, and made numerous reforms in the Raj, culminating in the Government of India Act (1935).

Africa was a very different case from Asia between the wars. Tropical Africa was not fully drawn into the colonial system before the end of the 19th century, excluding only the complexities of the Union of South Africa (busily introducing racial segregation from 1924 and thus catalyzing the anti-colonial political growth of half the continent) and the Empire of Ethiopia. Colonial controls ranged between extremes. Economic growth was often curtailed. There were no indigenous nationalist groups with widespread popular support before 1939.

The United States

At end of the Spanish-American War, at the end of the 19th century, the United States of America held several colonial territories seized from Spain, among them the Philippines and Puerto Rico. Although the United States had initially embarked upon a policy of colonization of these territories (and had fought to suppress local "insurgencies" there, such as in the Philippine-American War), by the 1930s, the U.S. policy for the Philippines had changed toward the direction of eventual self-government. Following the invasion and occupation of the Philippines by Japan during World War II, the Philippines gained independence peacefully from the United States in 1946.

However, other U.S. possessions, such as Puerto Rico, did not gain full independence. Puerto Ricans have held U.S. citizenship since 1917, but do not vote in federal elections or pay federal taxes. Puerto Rico achieved self-government in 1952 and became a commonwealth in association with the United States. Puerto Rico was taken off the UN list of non-sovereign territories in 1953 through resolution 748. In 1967, 1993 and 1998, Puerto Rican voters rejected proposals to grant the territory statehood or independence. Nevertheless, the island's political status remains a hot topic of debate.

Japan

As the only Asian nation to become a colonial power during the modern era, Japan had gained several substantial colonial concessions in east Asia such as Taiwan and Korea. Pursuing a colonial policy comparable to those of European powers, Japan settled significant populations of ethnic Japanese in its colonies while simultaneously suppressing indigenous ethnic populations by enforcing the learning and use of the Japanese language in schools. Other methods such as public interaction, and attempts to eradicate the use of Korean and Taiwanese (Min Nan) among the indigenous peoples, were seen to be used. Japan also set up the Imperial university in Korea (Keijo Imperial University) and Taiwan (Taihoku University) to compel education.

World War II gave Japan occasion to conquer vast swaths of Asia, sweeping into China and seizing the Western colonies of Vietnam, Hong Kong, the Philippines, Burma, Malaya, Timor and Indonesia among others, albeit only for the duration of the war. Following its surrender to the Allies in 1945, Japan was deprived of all its colonies. Japan further claims that the southern Kuril Islands are a small portion of its own national territory, colonized by the Soviet Union.

French Decolonization

After World War I, the colonized people were frustrated at France's failure to recognize the effort provided by the French colonies (resources, but more importantly colonial troops - the famous tirailleurs). Although in Paris the Great Mosque of Paris was constructed as recognition of these efforts, the French state had no intention to allow self-rule, let alone independence to the colonized people. Thus, nationalism in the colonies became stronger in between the two wars, leading to Abd el-Krim's Rif War (1921-1925) in Morocco and to the creation of Messali Hadj's Star of North Africa in Algeria in 1925. However, these movements would gain full potential only after World War II. The October 27, 1946 Constitution creating the Fourth Republic substituted the French Union to the colonial empire. On the night of March 29, 1947, a nationalist uprising in Madagascar led the French government led by Paul Ramadier (Socialist) to violent repression: one year of bitter fighting, in which 90,000 to 100,000 Malagasy died. On May 8, 1945, the Sétif massacre took place in Algeria.

In 1946, the states of French Indochina withdrew from the Union, leading to the Indochina War (1946-54) against Ho Chi Minh, who had been a co-founder of the French Communist Party in 1920 and had founded the Vietminh in 1941. In 1956, Morocco and Tunisia gained their independence, while the Algerian War was raging (1954-1962). With Charles de Gaulle's return to power in 1958 amidst turmoil and threats of a right-wing coup d'Etat to protect "French Algeria", the decolonization was completed with the independence of Sub-Saharan Africa's colonies in 1960 and the March 19, 1962 Evian Accords, which put an end to the Algerian war. The OAS movement unsuccessfully tried to block the accords with a series of bombings, including an attempted assassination against Charles de Gaulle.

To this day, the Algerian war — officially called until the 1990s a "public order operation" — remains a trauma for both France and Algeria. Philosopher Paul Ricœur has spoken of the necessity of a "decolonization of memory", starting with the recognition of the 1961 Paris massacre during the Algerian war and the recognition of the decisive role of African and especially North African immigrant manpower in the Trente Glorieuses post-World War II economic growth period. In the 1960s, due to economic needs for post-war reconstruction and rapid economic growth, French employers actively sought to recruit manpower from the colonies, explaining today's multiethnic population.

The Soviet Union and anti-colonialism

The Soviet Union sought to effect the abolishment of colonial governance by Western countries, either by direct subversion of Western-leaning or -controlled governments or indirectly by influence of political leadership and support. Many of the revolutions of this time period were inspired or influenced in this way. The conflicts in Vietnam, Nicaragua, Congo, and Sudan, among others, have been characterized as such.

Most Soviet leaders expressed the Marxist-Leninist view that imperialism was the height of capitalism, and generated a class-stratified society. It followed, then, that Soviet leadership would encourage independence movements in colonized territories, especially as the Cold War progressed. Because so many of these wars of independence expanded into general Cold War conflicts, the United States also supported several such independence movements in opposition to Soviet interests.

During the Vietnam War, Communist countries supported anti-colonialist movements in various countries still under colonial administration through propaganda, developmental and economic assistance, and in some cases military aid. Notably among these were the support of armed rebel movements by Cuba in Angola, and the Soviet Union (as well as the People's Republic of China) in Vietnam.

It is noteworthy that while England, Spain, Portugal, France, and the Netherlands took colonies overseas, the Russian Empire expanded via land across Asia. The Soviet Union did not make any moves to return this land.

The emergence of the Third World (1945-)

The term "Third World" was coined by French demographer Alfred Sauvy in 1952, on the model of the Third Estate, which, according to the Abbé Sieyès, represented everything, but was nothing: "...because at the end this ignored, exploited, scorned Third World like the Third Estate, wants to become something too" (Sauvy). The emergence of this new political entity, in the frame of the Cold War, was complex and painful. Several tentatives were made to organize newly independent states in order to oppose a common front towards both the US's and the USSR's influence on them, with the consequences of the Sino-Soviet split already at works. Thus, the Non-Aligned Movement constituted itself, around the main figures of Nehru, the leader of India, The Indonesian prime minister, Tito the Communist leader of Yugoslavia, and Nasser, head of Egypt who successfully opposed the French and British imperial powers during the 1956 Suez crisis. After the 1954 Geneva Conference which put an end to the French war against Ho Chi Minh in Vietnam, the 1955 Bandung Conference gathered Nasser, Nehru, Tito, Sukarno, the leader of Indonesia, and Zhou Enlai, Premier of the People's Republic of China. In 1960, the UN General Assembly voted the Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples. The next year, the Non-Aligned Movement was officially created in Belgrade (1961), and was followed in 1964 by the creation of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) which tried to promote a New International Economic Order (NIEO). The NIEO was opposed to the 1944 Bretton Woods system, which had benefitted the leading states which had created it, and remained in force until after the 1973 oil crisis. The main tenets of the NIEO were:

- Developing countries must be entitled to regulate and control the activities of multinational corporations operating within their territory.

- They must be free to nationalise or expropriate foreign property on conditions favourable to them.

- They must be free to set up associations of primary commodities producers similar to the OPEC (Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, created on September 17, 1960 to protest pressure by major oil companies (mostly owned by U.S., British, and Dutch nationals) to reduce oil prices and payments to producers.); all other States must recognize this right and refrain from taking economic, military, or political measures calculated to restrict it.

- International trade should be based on the need to ensure stable, equitable, and remunerative prices for raw materials, generalized non-reciprocal and non-discriminatory tariff preferences, as well as transfer of technology to developing countries; and should provide economic and technical assistance without any strings attached.

The UNCTAD however wasn't very effective in implementing this New International Economic Order (NIEO), and social and economic inequalities between industrialized countries and the Third World kept on growing through-out the 1960s until the 21st century. The 1973 oil crisis which followed the Yom Kippur War (October 1973) was triggered by the OPEC which decided an embargo against the US and Western countries, causing a fourfold increase in the price of oil, which lasted five months, starting on October 17 1973, and ending on March 18 1974. OPEC nations then agreed, on January 7 1975, to raise crude oil prices by 10%. At that time, OPEC nations — including many who had recently nationalised their oil industries — joined the call for a New International Economic Order to be initiated by coalitions of primary producers. Concluding the First OPEC Summit in Algiers they called for stable and just commodity prices, an international food and agriculture program, technology transfer from North to South, and the democratization of the economic system. But industrialized countries quickly began to look for substitutes to OPEC petroleum, with the oil companies investing the majority of their research capital in the US and European countries or others, politically sure countries. The OPEC lost more and more influence on the world prices of oil.

The second oil crisis occurred in the wake of the 1979 Iranian Revolution. Then, the 1982 Latin American debt crisis exploded in Mexico first, then Argentina and Brazil, whom proved unable to pay back their debts, jeopardizing the existence of the international economic system.

The 1990s were characterized by the prevalence of the Washington consensus on neoliberal policies, "structural adjustment" and "shock therapies" for the former Communist states.

Assassinated anticolonialist leaders

A non-exhaustive list of assassinated leaders would include:

- Ruben Um Nyobé, leader of the Union of the Peoples of Cameroon (UPC), killed by the French army on September 13, 1958

- Barthélemy Boganda, leader of a nationalist Central African Republic movement, who died in a plane-crash on March 29, 1959, eight days before the last elections of the colonial era.

- Félix-Roland Moumié, successor to Ruben Um Nyobe at the head of the UPC, assassinated in Geneva in 1960 by the SDECE (French secret services).[1]

- Patrice Lumumba, the first Prime minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, was assassinated on January 17, 1961.

- Burundi nationalist Louis Rwagasore was assassinated on October 13, 1961, while Pierre Ngendandumwe, Burundi's first Hutu prime minister, was also murdered on January 15, 1965.

- Sylvanus Olympio, the first president of Togo, was assassinated on January 13, 1963. He would be replaced by Gnassingbé Eyadéma, who ruled Togo for nearly forty years; he died in 2005 and was succeeded by his son Faure Gnassingbé.

- Mehdi Ben Barka, the leader of the Moroccan National Union of Popular Forces (UNPF) and of the Tricontinental Conference, which was supposed to prepare in 1966 in Havana its first meeting gathering national liberation movements from all continents — related to the Non-Aligned Movement, but the Tricontinal Conference gathered liberation movements while the Non-Aligned were for the most part states — was "disappeared" in Paris in 1965.

- Nigerian leader Ahmadu Bello was assassinated in January 1966.

- Eduardo Mondlane, the leader of FRELIMO and the father of Mozambican independence, was assassinated in 1969, allegedly by Aginter Press, the Portuguese branch of Gladio, NATO's paramilitary organization during the Cold War.[2]

- Pan-Africanist Tom Mboya was killed on July 5, 1969.

- Abeid Karume, first president of Zanzibar, was assassinated in April 1972.

- Amílcar Cabral was murdered on January 20, 1973.

- Outel Bono, Chadian opponent of François Tombalbaye, was assassinated on August 26, 1973, making yet another example of the existence of the Françafrique, designing by this term post-independent neocolonial ties between France and its former colonies.

- Herbert Chitepo, leader of the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU), was assassinated on March 18, 1975.

- Óscar Romero, prelate archbishop of San Salvador and proponent of liberation theology, was assassinated on March 24, 1980

- Dulcie September, leader of the African National Congress (ANC), who was investigating an arms trade between France and South Africa, was murdered in Paris on March 29, 1988, a few years before the end of the apartheid regime.

Many of these assassinations are still unsolved cases as of 2007, but foreign power interference is undeniable in many of these cases — although others were for internal matters. To take only one case, the investigation concerning Mehdi Ben Barka is continuing to this day, and both France and the United States have refused to declassify files they acknowledge having in their possession[3] The Phoenix Program, a CIA program of assassination during the Vietnam War, should also be named.

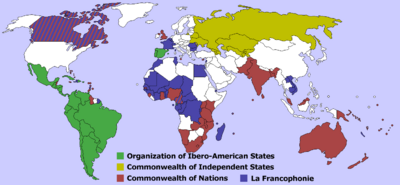

Post-colonial organizations

Due to a common history and culture, former colonial powers created institutions which more loosely associated their former colonies. Membership is voluntary, and in some cases can be revoked if a member state loses some objective criteria (usually a requirement for democratic governance). The organizations serve cultural, economic, and political purposes between the associated countries, although no such organization has become politically prominent as an entity in its own right.

| Former Colonial Power | Organization | Founded |

|---|---|---|

| Britain | Commonwealth of Nations | 1931 |

| Commonwealth Realms | 1931 | |

| Associated states | 1967 | |

| France | French Union | 1946 |

| French Community | 1958 | |

| Francophonie | 1970 | |

| Spain & Portugal | Latin Union | 1954 |

| Organization of Ibero-American States | 1991 | |

| Community of Portuguese Language Countries | 1996 | |

| United States | Commonwealths | 1934 |

| Freely Associated States | 1982 | |

| European Union | ACP countries | 1975 |

Differing perspectives

There is quite a bit of controversy over decolonisation. The end goal tends to be universally regarded as good, but there has been much debate over the best way to grant full independence.

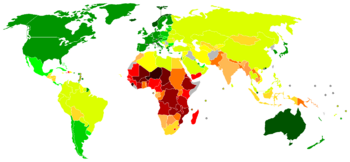

Decolonization and political instability

Some say the post–World War II decolonisation movement was too rushed, especially in Africa, and resulted in the creation of unstable regimes in the newly independent countries. Thus causing war between and within the new independent nation-states.

Others argue that this instability is largely the result of problems from the colonial period, including arbitrary nation-state borders, lack of training of local populations and disproportional economy. However by the 20th century most colonial powers were slowly being forced by the moral beliefs of population to increase the welfare of their colonial subjects.

Some would argue a form of colonialisation still exists in the form of american economic colonialism in the form of U.S owned multinational corporations.

Economic effects

Effects on the colonizers

John Kenneth Galbraith argues that the post-World War II decolonization was brought about for economic reasons. In A Journey Through Economic Time, he writes, "The engine of economic well-being was now within and between the advanced industrial countries. Domestic economic growth — as now measured and much discussed — came to be seen as far more important than the erstwhile colonial trade... The economic effect in the United States from the granting of independence to the Philippines was unnoticeable, partly due to the Bell Trade Act, which allowed American monopoly in the economy of the Philippines. The departure of India and Pakistan made small economic difference in Britain. Dutch economists calculated that the economic effect from the loss of the great Dutch empire in Indonesia was compensated for by a couple of years or so of domestic post-war economic growth. The end of the colonial era is celebrated in the history books as a triumph of national aspiration in the former colonies and of benign good sense on the part of the colonial powers. Lurking beneath, as so often happens, was a strong current of economic interest — or in this case, disinterest."

Part of the reason for the lack of economic impact felt by the colonizer upon the release of the colonized was that costs and benefits were not eliminated, but shifted. The colonizer no longer had the burden of obligation, financial or otherwise, to their colony. The colonizer continued to be able to obtain cheap goods and labor as well as economic benefits (see Suez Canal Crisis) from the former colonies. Financial, political and military pressure could still be used to achieve goals desired by the colonizer. The most obvious difference is the ability of the colonizer to disclaim responsibility for the colonized.

Effects on the former colonies

- Further information: Third World debt