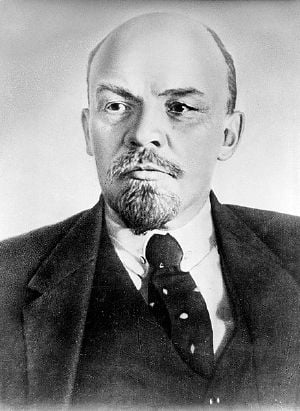

Marxism-Leninism is an adaptation of Marxism developed by Vladimir Lenin, which led to the first successful communist revolution in Lenin's Russia in November 1917. As such, it formed the ideological foundation for the world communist movement centering on the Soviet Union. In the twentieth century, all nations calling themselves communist and communist parties in other nations were founded on Marxist-Leninist principles. The core ideological features of Marxism-Leninism include the belief that a revolutionary proletarian class would not emerge automatically from capitalism. Instead, there was the need for a professional revolutionary vanguard party to lead the working class in the violent overthrow of capitalism, to be followed by a dictatorship of the proletariat as the first stage of moving toward communism. Marxism-Leninism also maintained that workers in the most advanced capitalist countries had not opted for revolution because capitalism had moved to a new stage through the exportation of capital to colonies, which allowed capitalists to exploit such colonies and enrich markets and "bribe" workers in developed countries with higher wages. Marxism-Leninism, therefore, saw the developing world as the frontline in the struggle against imperialism. As those markets were cut off through national liberation, capitalism would implode in the developed world and communist revolution would occur there as well.

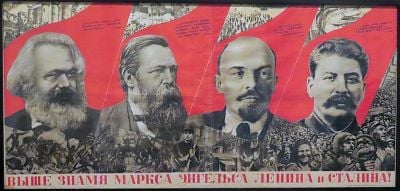

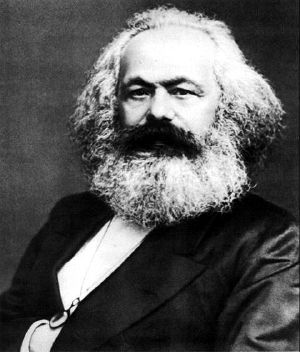

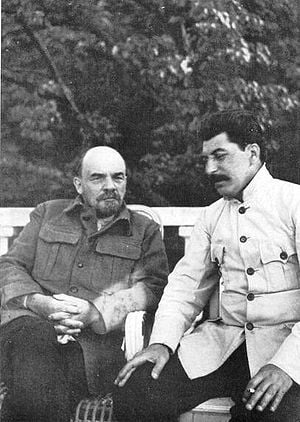

Communist parties subscribed to the teachings and legacy of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels (Marxism), as interpreted by Lenin. The term Marxism-Leninism was most often used by the Soviet Union and its supporters who held that Lenin's legacy was successfully advanced by Joseph Stalin, although Trotskyists and Maoists are also technically Marxist-Leninists. The term was also used by Soviet Communists who repudiated Stalin, such as the supporters of Nikita Khrushchev. Contemporary Marxist-Leninist regimes today include Vietnam, Laos, and Cuba. China and North Korea have each sought to distance themselves somewhat from Marxism-Leninism but have not repudiated the basic principles of the Communist revolutions that created these governments.

History of the term

Although Lenin himself never used the term "Leninism," his interpretation of Marx's teaching became the impetus for the founding of the Soviet Union and the numerous Marxist-Leninist parties inspired by the Russian Revolution. Lenin's ideas diverged from classical Marxist theory on several important points (see Marxism). Bolshevik communists‚ÄĒthe followers of Lenin‚ÄĒsaw these differences as advancements of Marxism rather than a divergence from it. According to Lenin, these changes were made necessary by the advent of Imperialism, which enabled capitalist nations to export goods to colonies and profit both from the sale of such goods and from the financing of the purchase of such goods with high interest loans. A small portion of the profits that resulted from such practices were passed on to industrial workers to prevent them from attaining the revolutionary consciousness which Marx had predicted would emerge. Because of this, Lenin taught, the first Communist revolution would not necessarily occur in industrialized Europe as Marx said it would, but in that nation in which a disciplined "vanguard" would seize power and create the "proletarian dictatorship."

| ‚Äú | We need the real, nation-wide terror which reinvigorates the country and through which the Great French Revolution achieved glory.[1] | ‚ÄĚ |

After Lenin's death, his ideology and contributions to Marxist theory were termed "Marxism-Leninism," or sometimes only "Leninism." Marxism-Leninism soon became the official name for the ideology of the Comintern and of communist parties around the world. To a large extent, the adaptations that Lenin made to Marxism provided a framework for communist activity in revolutionary movements throughout the world. Marxism-Leninism, unlike Marxism per se, took a far more practical approach to the attainment of political power. Its focus was the achievement of power rather than ideology. It, therefore, saw the need to train revolutionary cadres. It recognized that an opportune seizure should not be dismissed simply because the ideal textbooks conditions described by Marx were lacking. It portrayed Imperialism rather than Capitalism as the enemy and it emphasized the need for a disciplined communist party rather than a "big tent" approach as crucial for advancing the Communist cause. It maintained that Communism could be established during the period of development of mainstream communism. Like Lenin, Stalin's approach to communism was a highly practical, although brutal one. Lenin negotiated a rapid retreat of Russian forces from World War I and Stalin opted for "socialism in one nation" as being important than attempting to export the Soviet revolution to other parts of the world and create enemies at a time when the USSR was not politically and economically prepared to face such enemies. Understandably, Trotskyists who favored export of the Soviet revolution believed that that Stalinism contradicted authentic Marxism and Leninism, and they initially used the term "Bolshevik-Leninism" to describe their own ideology of anti-Stalinist and anti-Maoist Communism.

After the Sino-Soviet split in 1960, the Soviet Union and the People's Republic of China each claimed to be the true intellectual heir to Marxism-Leninism and the Chinese were especially critical of post-Stalin leadership in the USSR, beginning with Nikita Khrushchev. In China, the claim that Mao had "adapted Marxism-Leninism to Chinese conditions" evolved into the idea that he had updated it in a fundamental way applying it to the world as a whole. Consequently, the term "Marxism-Leninism-Mao Zedong Thought" (commonly known as Maoism) was increasingly used by the Chinese to describe the official state ideology and this also served as the ideological basis of parties around the world who sympathized with the Communist Party of China. Following the death of Mao, American Maoists associated with the Revolutionary Communist Party (USA) coined the term Marxism-Leninism-Maoism, arguing that Maoism was a more advanced stage of Marxism.

In North Korea, Marxism-Leninism was officially superseded in 1977 by Juche (self-reliance), in which concepts of class and class struggle, in other words Marxism itself, no longer play a significant role due in part to all remnants of Capitalism and private ownership having been eradicated. However, the government is still sometimes referred to as Marxist-Leninist‚ÄĒor, even Stalinist‚ÄĒdue to the nature of its political and economic structure.

The other three communist states existing today‚ÄĒCuba, Vietnam, and Laos‚ÄĒstill hold Marxism-Leninism as their official ideology, although they give it different interpretations in terms of practical policy.

Distinction from classical Marxism

The most crucial difference between "classical" Marxism and Marxism-Leninism has to do with the fact that the early twentieth century working class had not developed in the way that Marx and Engels had predicted, but was adopting "bourgeois" values instead of supporting the communist cause. In accord with Marx's Laws of Economic Movement, the working class was supposed to develop a sense of class solidarity and a revolutionary consciousness due to increasing poverty because of machines replacing workers. As per the per the Marxist axiom that only labor produces profit, these circumstances would also result in a decrease in profits, resulting in a concentration of capital where less and less businesses would survive and so the Capitalist enemy would become increasingly targeted and a focus of antagonism. According to Marx's theories, these conditions would foster an overwhelming revolutionary sentiment. The ruling class, however, would only repress this democratic urge toward socialism, resulting eventually in a reaction that would lead to violent revolution. A "dictatorship of the proletariat" would be imposed by the workers themselves and would lead society in the transition from Socialism to Communism.

Lenin perceived that the workers in the industrialized nations were not developing the revolutionary consciousness that Marx foresaw. In Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism, written in 1916, he theorized that the imperialist powers had temporarily circumvented the process Marx envisioned, by exporting capital and products to their colonies and, in turn, claiming the wealth and raw materials of these colonies.[2] The result was that the Capitalists could afford to provide their workers with just enough benefits to keep them satisfied and postpone any revolutionary ambition. As a result, Lenin insisted that only a "vanguard party" of the proletariat, comprised primarily of intellectuals rather than the workers, needed to foster the necessary revolutionary consciousness to overthrow the Capitalists. Lenin also advocating extending the target population for such revolutionary fervor to include peasants and the Russian soldiers involved in a seemingly hopeless war in Europe. In order to do this, they would need to use any means necessary to seize power and establish the proletarian dictatorship. After the Russian Revolution, Lenin saw that "reactionary forces" were so ingrained in Russian society that he maintained that a "Red Terror" would need to be organized by the Bolshevik state in order to root out such counter-revolutionary institutions as the "bourgeois press" and religious "superstition."

| ‚Äú | To tolerate the bourgeois newspapers would mean to cease being a Socialist. When one makes a Revolution, one cannot mark time; one must always go forward-or go back. He who now talks about the 'freedom of the Press' goes backward, and halts our headlong course toward Socialism.‚ÄĒV.I Lenin [3] | ‚ÄĚ |

This version of Marx's the "dictatorship of the proletariat"‚ÄĒin which a small Communist party, backed by ruthless police power, determined what was good for the workers whether they liked it or not resulted when Lenin failed to gain a majority of parliamentary support following the Bolshevik Revolution. As the forces of "bourgeois democracy," religion, and other counter-revolutionary movements remained obstacles, Stalin would prolong the dictatorship of the proletariat, justifying the totalitarian regime of the Soviet Union because of the danger of reactionary efforts to suppress the revolution. Although later leaders, notably Khrushchev, attempted to speculate on when such dictatorship might end their target dates came and gone and the stage from socialism to Communism was extended through an intermittent period referred to in the final years of the Soviet Union as "developed socialism."

Marxism-Leninism in the Soviet Union

Marxism-Leninism in the Soviet Union was a selected mix of the prolific writings of Marx and Lenin, in addition to inclusions made by Soviet political authorities. Marxism-Leninism was both the official ideology of the Soviet Union, and the most influential strain of Marxism.

Marxist-Leninist practices changed slightly with each successive era of Soviet Communist Party leaders. Khrushchev strongly opposed the establishment of personality cults like that of the Stalin era, which it described as alien to Leninism. Leonid Brezhnev oversaw a period in Soviet history where the dissent fostered by Khrushchev was again discouraged. It is largely accepted that Marxism-Leninism ended in the Soviet Union with the openness of criticism and rejection of basic tenets of the ideology during Gorbachev's policies of Perestroika and Glasnost.[4]

Current usage

Most Communist parties today continue to regard Marxism-Leninism as their basic ideology, although many have modified it to adapt to new political conditions. However, several parties, especially those previously associated with Eurocommunism, have distanced themselves from Leninism and in many cases omitted it from their official documents. Some have started identifying themselves as "Marxist and Leninist" rather than "Marxist-Leninist."

In party names, the appellation "Marxist-Leninist" is normally used by a Communist party who wishes to distinguish itself from some other (and presumably 'revisionist') communist party in the same country. Most often, parties who place the term "Marxist-Leninist" in their official name are those originating from the anti-revisionist tradition, such as Maoist groups.

See also

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ Lenin quotes thinkexist.com.

- ‚ÜĎ Vladimir Il Ļich Lenin, Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism: A Popular Outline (International Publishers, 1982, ISBN 978-0717800988).

- ‚ÜĎ Ten Days That Shook the World/Chapter XI Wikisource. Retrieved October 19, 2022.

- ‚ÜĎ Archie Brown, (ed.), The Demise of Marxism-Leninism in Russia (Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004, ISBN 9780333651247).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Brown, Archie (ed.). The Demise of Marxism-Leninism in Russia. Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004. ISBN 9780333651247

- Brzezinski, Zbigniew. Ideology and Power in Soviet Politics. New York: Praeger, 1976. ISBN 978-0837188805

- Crossman, Richard H. (ed.). The God That Failed. Columbia University Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0231123952

- Evans, Alfred B. Soviet Marxism-Leninism The Decline of an Ideology. Westport, CT: Praeger, 1993. ISBN 9780275947637

- Lenin, Vladimir Il Ļich. Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism: A Popular Outline. International Publishers, 1982. ISBN 978-0717800988

- Luxemburg, Rosa. The Russian Revolution, and Leninism or Marxism? Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1961. ISBN 0472060570

- Michael, Franz, Carl A. Linden, Jan S. Prybyla, and Jurgen Domes. China and the Crisis of Marxism-Leninism. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1990. ISBN 9780813379111

- Serge, Victor. From Lenin to Stalin. New York: Monad Press; distributed by Pathfinder Press, 1973. ISBN 978-0873488846

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.