| Western Philosophy Nineteenth century philosophy | |

|---|---|

| |

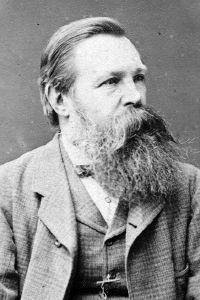

| Name: Friedrich Engels | |

| Birth: November 28, 1820 (Wuppertal, Germany) | |

| Death: August 5, 1895 (London, England) | |

| School/tradition: Marxism | |

| Main interests | |

| Political philosophy, Politics, Economics, class struggle | |

| Notable ideas | |

| Co-founder of Marxism (with Karl Marx), Marx's theory of alienation and exploitation of the worker, historical materialism | |

| Influences | Influenced |

| Kant, Hegel, Feuerbach, Stirner, Smith, Ricardo, Rousseau, Goethe, Fourier | Luxemburg, Lenin, Trotsky, Mao, Guevara, Sartre, Debord, Frankfurt School, Negri, more... |

Friedrich Engels (November 28, 1820 â August 5, 1895), a nineteenth century German political philosopher, collaborated closely with Karl Marx in the foundation of modern Communism. The son of a textile manufacturer, he became a socialist, and after observing the appalling situation of British factory laborers while managing a factory in Manchester, England, he wrote his first major work, The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844 (1845). In 1844, he met Marx in Paris, beginning a lifelong collaboration. He and Marx wrote The Communist Manifesto (1848) and other works. After the failure of the revolutions of 1848, Engels settled in England. With Marx, he helped found (1864) the International Workingmen's Association. Engels supported Marx financially while he wrote the first volume of Das Kapital (1867).

After Marxâs death, Engels edited volume's 2 and 3 from Marx's drafts and notes (the final volume was completed by Karl Kautsky). Engels contributed in questions of nationality, military affairs, the sciences, and industrial operations, and is generally credited with shaping two of the major philosophical components of Marxism: Historical materialism and dialectical materialism. His major works include Anti-Duhring (1878) and The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State (1884).

Life

Early years

Friedrich Engels was born November 28, 1820, in Barmen, Rhine Province of the kingdom of Prussia (now a part of Wuppertal in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany), as the eldest son of a German textile manufacturer, with whom he had a strained relationship.[1] Due to family circumstances, Engels dropped out of high school and was sent to work as a non-salaried office clerk at a commercial house in Bremen in 1838.[2] During this time, Engels began reading the philosophy of Hegel, whose teachings dominated German philosophy at the time. In September 1838, he published his first work, a poem titled The Bedouin, in the Bremisches Conversationsblatt No. 40. He also engaged in other literary and journalistic work.[3] In 1841, Engels joined the Prussian Army as a member of the Household Artillery. This position moved him to Berlin where he attended university lectures, began to associate with groups of Young Hegelians and published several articles in the Rheinische Zeitung.[4] Throughout his lifetime, Engels would point out that he was indebted to German philosophy because of its effect on his intellectual development.[5]

England

In 1842, the twenty-two year old Engels was sent to Manchester, England, to work for the textile firm of Ermen and Engels, in which his father was a shareholder.[6] Engels' father thought working at the Manchester firm might make Engels reconsider the radical leanings that he had developed in high school.[7] On his way to Manchester, Engels visited the office of the Rheinische Zeitung and met Karl Marx for the first time, though the pair did not impress each other.[8] In Manchester, Engels met Mary Burns, a young woman with whom he began a relationship that lasted until her death in 1862.[9] Mary acted as his guide in Manchester and helped introduce Engels to the British working class. Despite their lifelong relationship, the two were never married because Engels was against the institution of marriage, which he saw as unnatural and unjust.[10]

During his time in Manchester, Engels took notes and personally observed the terrible working conditions of British workers. These notes and observations, along with his experience working in his father's commercial firm, formed the basis for his first book, The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844. While writing Conditions of the Working Class, Engels continued to be involved with radical journalism and politics. He frequented some members of the English labor and Chartist movements and wrote for several different journals, including The Northern Star, Robert Owenâs New Moral World, and the Democratic Review newspaper.[11]

Paris

After a productive stay in England, Engels decided to return to Germany, in 1844. While traveling back to Germany, he stopped in Paris to meet Karl Marx, with whom he had corresponded earlier. Marx and Engels met at the CafĂ© de la RĂ©gence on the Place du Palais, August 28, 1844. The two became close friends and remained so for their entire lives. Engels ended up staying in Paris in order to help Marx write, The Holy Family, an attack on the Young Hegelians and the Bauer brothers. Engels' earliest contribution to Marx's work was writing for the Deutsch-französische JahrbĂŒcher journal, which was edited by both Marx and Arnold Ruge in Paris in the same year.[12]

Barmen

Returning to Barmen, Engels published Die Lage der arbeitenden Klasse in England (1845; The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844, 1887), a classic in a field that later became Marx's specialty. Their first major joint work was Die deutsche Ideologie (1845; The German Ideology), which, however, was not published until more than eighty years later. It was a highly polemical critique that denounced and ridiculed certain of their earlier Young Hegelian associates and then proceeded to attack various German socialists who rejected the need for revolution. Marx's and Engels' own constructive ideas were inserted here and there, always in a fragmentary manner and only as corrective responses to the views they were condemning.

Brussels, London, and Paris

In 1845, Engels rejoined Marx in Brussels and endorsed his newly formulated materialistic interpretation of history, which assumed the eventual realization of a communist society. Between 1845 and 1848, Engels and Marx lived in Brussels, spending much of their time organizing the city's German workers. Shortly after their arrival, they contacted and joined the underground German Communist League and were commissioned, by the League, to write a pamphlet explaining the principles of Communism.

In the summer of 1845, Engels took Marx on a tour of England. Afterward, he spent time in Paris, trying to convert various groups of German Ă©migrĂ© workers, including a secret socialist society, the League of the Just, and French socialists, to his and Marxâs views. In June 1847, when the League of the Just held its first congress in London, Engels was instrumental in bringing about its transformation into the Communist League.

Together, he and Marx persuaded a second Communist Congress in London to adopt their ideas, and were authorized to draft a statement of communist principles. The Manifest der kommunistischen Partei (The Manifesto of the Communist Party, commonly called the Communist Manifesto) was first published on February 21, 1848.[13] Though primarily written by Marx, it included many of Engelâs preliminary definitions from GrundsĂ€tze des Kommunismus (1847; Principles of Communism).

Return to Prussia

During the month of February 1848, there was a revolution in France that eventually spread to other Western European countries. Engels and Marx returned to the city of Cologne in their home country of Prussia. There, they created and served as editors of a new daily newspaper called the Neue Rheinische Zeitung.[14] However, the newspaper was suppressed during a Prussian coup d'Ă©tat in June 1849. The coup d'Ă©tat separated Engels and Marx, who lost his Prussian citizenship, was deported, and fled to Paris and then London. Engels remained in Prussia and took part in an armed uprising in South Germany as an aide-de-camp in the volunteer corps of the city of Willich.[15] When the uprising was crushed, Engels escaped by traveling through Switzerland as a refugee and returned to England.[16]

Back in Manchester

Engels and Marx were reunited in London, where they reorganized the Communist League and drafted tactical directives for the Communists, believing that another revolution was imminent. To support Marx and himself, Engels accepted a subordinate position in the commercial firm in which his father held shares, Ermen and Engels, and eventually worked his way up to become a joint proprietor in 1864.[17] He never allowed his communist principles and his criticism of capitalism to interfere with the profitable operations of the firm, and was able to supply Marx with a constant stream of funds. When he sold his partnership in 1869, in order to concentrate more on his studies,[18] he received enough money to live comfortably until his death in 1895, and to provide Marx with an annual grant of ÂŁ350, with additional amounts to cover all contingencies.

Forced to live in Manchester, Engels kept up a constant correspondence with Marx and frequently wrote newspaper articles for him. He was the author of the articles which appeared in the New York Tribune under Marx's name in (1851â52). They were later published under Engels' name as Revolution and Counter-Revolution in Germany in 1848 (1896). In 1870, Engels moved to London and lived with Marx until the latter's death in 1883.[19] His London home at this time and until his death was 122 Regent's Park Road, Primrose Hill, NW1.[20]

Later years

Engelâs reviews of Marxâs Das Kapital (Capital), helped to establish it as the centerpiece of Marxist thought and to popularize Marxist views. Almost single-handedly, he wrote Herrn Eugen DĂŒhrings UmwĂ€lzung der Wissenschaft (1878; Herr Eugen DĂŒhring's Revolution in Science), the book that did most to promote Marxâs ideas, and undermined the influence of the Berlin professor, Karl Eugen DĂŒhring, who was threatening to supplant Marx's influence among German Social Democrats.

After Marx's death in 1883, Engels acted as the foremost authority on Marx and Marxism. He used Marx's uncompleted manuscripts and rough notes to complete volume's 2 and 3 of Das Kapital (1885 and 1894) and wrote introductions to new editions of Marx's works, as well as articles on a variety of subjects.

Engels' last two publications were Der Ursprung der Familie, des Privateigenthums und des Staats (1884; The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State) and Ludwig Feuerbach und der Ausgang der klassischen deutschen Philosophie (1888; Ludwig Feuerbach and the Outcome of Classical German Philosophy). He corresponded extensively with German Social Democrats and followers everywhere, in order to perpetuate the image of Marx and to foster some degree of conformity among the âfaithful.â

Engels died of throat cancer in London in 1895.[21] Following cremation at Woking, his ashes were scattered off Beachy Head, near Eastbourne, as he had requested.

Thought and works

Engels created a philosophical framework in which Marxâs ideas could be understood, by proposing that philosophy had been developing progressively through history until it culminated in Hegelâs systematic idealism. He claimed that Marx had applied Hegelâs insights to the physical world, and believed that modern natural and political science were reaching a point where they could realize an ideal physical existence and an ideal society. He said that Marx had developed a dialectical method which was equally applicable in explaining nature, the progress of history, and the progress of human thought, and that his âmaterialist conceptionâ had enabled him to analyze capitalism and unlock the âsecretâ of surplus value. These concepts were the basis of a âscientific socialismâ which would provide the direction and insight to transform society and solve the problems of poverty and exploitation.

Besides relying on Engels for material support for his work and his publications Marx also benefited from his knowledge of business practices and industrial operations. Engels believed that the concept of monogamous marriage had been created from the domination of men over women, and tied this argument to communist thought by arguing that men had dominated women just as the [capitalism|capitalist]] class had dominated workers. Since the 1970s, some critics have challenged Engelâs view that scientific socialism is an accurate representation of Marxâs intentions, and he has even been blamed for some of the errors in Marxâs theory.

Major Works

The Holy Family (1844)

The Holy Family, written by Marx and Engels in November 1844, is a critique of the Young Hegelians and their thought, which was very popular in academic circles at the time. The title was suggested by the publisher and was intended as a sarcastic reference to the Bauer Brothers and their supporters.[22] The book created a controversy in the press. Bruno Bauer attempted a refutation in an article which was published in Wigand's Vierteljahrsschrift in 1845, claiming that Marx and Engels misunderstood what he was trying to say. Marx later replied with his own article in the journal, Gesellschaftsspiegel, in January 1846. Marx also discussed the argument in Chapter 2 of The German Ideology.[23]

The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844 (1844)

The Condition of the Working Class is a detailed description and analysis of the appalling conditions of the working class in Britain and Ireland which Engels observed during his stay in England. It was originally intended for a German audience. The work contained many seminal thoughts on the state of socialism and its development.

Almost fifty years later, in his preface to the 1892 edition, Engels said of himself:

The author, at that time, was young, twenty-four years of age, and his production bears the stamp of his youth with its good and its faulty features, of neither of which he feels ashamed⊠The state of things described in this book belongs to-day, in many respects, to the past, as far as England is concerned. Though not expressly stated in our recognized treatises, it is still a law of modern Political Economy that the larger the scale on which capitalistic production is carried on, the less can it support the petty devices of swindling and pilfering which characterize its early stagesâŠ

But while England has thus outgrown the juvenile state of capitalist exploitation described by me, other countries have only just attained it. France, Germany, and especially America, are the formidable competitors who, at this momentâas foreseen by me in 1844âare more and more breaking up Englandâs industrial monopoly. Their manufactures are young as compared with those of England, but increasing at a far more rapid rate than the latter; and, curious enough, they have at this moment arrived at about the same phase of development as English manufacture in 1844. With regard to America, the parallel is indeed most striking. True, the external surroundings in which the working-class is placed in America are very different, but the same economical laws are at work, and the results, if not identical in every respect, must still be of the same order. Hence we find in America the same struggles for a shorter working-day, for a legal limitation of the working-time, especially of women and children in factories; we find the truck-system in full blossom, and the cottage-system, in rural districts, made use of by the 'bosses' as a means of domination over the workersâŠ

It will be hardly necessary to point out that the general theoretical standpoint of this bookâphilosophical, economical, politicalâdoes not exactly coincide with my standpoint of to-day. Modern international Socialism, since fully developed as a science, chiefly and almost exclusively through the efforts of Marx, did not as yet exist in 1844. My, book represents one of the phases of its embryonic development; and as the human embryo, in its early stages, still reproduces the gill-arches of our fish-ancestors, so this book exhibits everywhere the traces of the descent of Modern Socialism from one of its ancestors, German philosophy.[24]

The Communist Manifesto (1848)

Engels and Marx were commissioned by the German Communist League to publish a political pamphlet on communism in 1848. This slender volume is one of the most famous political documents in history. Much of its power comes from the concise way in which it is written. The Manifesto outlines a course of action to bring about the overthrow of the bourgeoisie (middle class) by the proletariat (working class) and establish a classless society, and presents an agenda of ten objectives to be accomplished.

The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State (1884)

The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State is a detailed seminal work connecting the development of capitalism with what Engels argues is an unnatural institution, family, designed to "privatize" wealth and human relationships against the way in which animals and early humans naturally evolved. It contains a comprehensive historical view of the family in relation to the issues of social class, female subjugation and ownership of private property.

Notes

- â Marxists.org, Letters of Karl Marx. Retrieved March 17, 2007.

- â Marxists.org, Friedrich Engels Biography. Retrieved March 17, 2007.

- â Marxists.org, Preface. Retrieved March 17, 2007.

- â Robert C. Tucker, The Marx-Engels Reader.

- â Marxists.org, Friedrich Engels Biography. Retrieved March 17, 2007.

- â Ibid.

- â Ibid.

- â Francis Wheen, Karl Marx: A Life.

- â BBC, Legacy of Friedrich Engels. Retrieved March 17, 2007.

- â Marxists.org, Origin and family. Retrieved March 17, 2007.

- â Marxists.org, Works. Retrieved March 17, 2007.

- â Marxists.org, Engels Publications. Retrieved March 17, 2007.

- â Marxists.org, Friedrich Engels Biography. Retrieved March 17, 2007.

- â Marxists.org, Friedrich Engels, 1893. Retrieved March 17, 2007.

- â Ibid.

- â Ibid.

- â BBC, Communism in Manchester. Retrieved March 17, 2007.

- â Marxists.org, Friedrich Engels Biography. Retrieved March 17, 2007.

- â Ibid.

- â English Heritage, London Blue Plaques. Retrieved May 6, 2008.

- â Marxists.org, Engels' Death. Retrieved March 17, 2007.

- â Marxists.org, Holy Family. Retrieved March 17, 2007.

- â Ibid.

- â Marixsts.org, Preface to the English Edition (1892). Retrieved March 17, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Carver, T. 1981. Engels. New York: Hill and Wang. ISBN 080901422X

- Engels, Freidrich and Leonard E. Mins. Frederick Engels on Capital; Synopsis, Reviews, Letters and Supplementary Material. New York: International Publishers, 1974.

- Nimtz, August H. Marx and Engels: Their Contribution to the Democratic Breakthrough. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 2000. ISBN 0585358362

- Ransom, Roger L. Twentieth Century Civilizations. Mason, Ohio: Thomson/Custom Pub., 2003.

- Tucker, R.C., K. Marx, and F. Engels. The Marx-Engels Reader. New York: Norton, 1978. ISBN 0393056848

External links

All links retrieved April 11, 2024.

- The Marx & Engels Internet Archive at Marxists.org.

- Marx/Engels Biographical Archive.

- Works by Friedrich Engels. Project Gutenberg.

General philosophy sources

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Paideia Project Online

- Project Gutenberg

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.