Western Sahara

| الصحراء الغربية (Arabic) Sahara Occidental (Spanish) Western Sahara |

||

|---|---|---|

| Capital (and largest city) | El Aaiún (Laâyoune)[1][2][3] | |

| Official languages | see respective claimants | |

| Spoken languages | Berber and Hassaniya Arabic are locally spoken Spanish and French are widely used |

|

| Demonym | Western Saharan | |

| Disputed sovereignty1 | ||

| - | Relinquished by Spain | 14 November 1975 |

| Area | ||

| - | Total | 266,000 km² (76th) 103,000 sq mi |

| - | Water (%) | negligible |

| Population | ||

| - | 2009 estimate | 513,000[4] (168th) |

| - | Density | 1.9/km² (237th) 5/sq mi |

| Currency | Moroccan Dirham (in the Morocco-controlled zone) Algerian Dinar with the Sahrawi Peseta being commemorative and not circulating (in the SADR-controlled zone)[5] (MAD) |

|

| Time zone | (UTC+0) | |

| Internet TLD | None; .eh reserved, not officially assigned | |

| Calling code | [[++212 (Tied with Morocco)]] | |

| 1 Mostly under administration of Morocco as its Southern Provinces. The Polisario Front controls border areas behind the border wall as the Free Zone, on behalf of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic. | ||

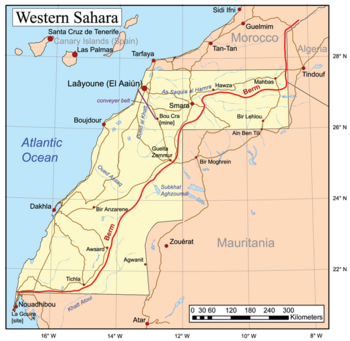

Western Sahara, located in northwestern Africa, is one of the most sparsely populated territories in the world, mainly consisting of desert flatlands.

Morocco and the Popular Front for the Liberation of Saguia al-Hamra and Rio de Oro (Polisario) independence movement dispute control of the territory, with Morocco having de facto control over most of the territory. Morocco bases its claims on historical proclamations by tribal chiefs of allegiance to Moroccan sultans. The Polisario Front was formed with Algerian, Libyan, and Soviet bloc backing as an independence movement when Spain still controlled the area as a colony. Today, geopolitical ambitions, hopes of exploiting natural resources, and concerns about the spread of terrorism in the region play a role in the failure to achieve an acceptable political settlement.

There is some concern that an independent Western Sahara, with its long, isolated borders, would not be able to adequately control its territory and might be subject to manipulation by Islamists or other radicals, including Al Qaeda, which is already active in the region. The result could be, some say, an unstable, violence-prone state reminiscent of Somalia. The degree to which Algeria, long the Polisario's patron, would influence such a state is also of concern, especially to Morocco.

Geography

Western Sahara is bordered by Morocco to the north, Algeria in the northeast, Mauritania to the east and south, and the Atlantic Ocean on the west. The land is some of the most arid and inhospitable on the planet, but is rich in phosphates in Bou Craa. The largest city is El Aaiún (Laayoune), which is home to two-thirds of the population.

Saguia el Hamra is the northern third and includes Laayoune. Río de Oro is the southern two-thirds (south of Cape Bojador), with the city of Dakhla. The peninsula in the extreme southwest, with the city of Lagouira, is called Ras Nouadhibou, Cap Blanc, or Cabo Blanco. The eastern side is part of Mauritania.

The climate is hot, dry desert; rain is rare; cold offshore air currents produce fog and heavy dew. Hot, dry, dust/sand-laden sirocco winds can occur during winter and spring; widespread harmattan haze exists 60 percent of the time, often severely restricting visibility.

The terrain is mostly low, flat desert with large areas of rocky or sandy surfaces rising to small mountains in the south and northeast. Along the coast, steep cliffs line the shore, and shipwrecks are visible. The lowest point is Sebjet Tah (-55 m) and the highest point (unnamed) is 463 m. Natural resources are phosphates and iron ore. Water and arable land are scarce.

Plant and animal life is restricted to those species adapted to desert conditions, such as fennec foxes, jerboas and other rodents, and hyenas. Reptiles include lizards and snakes.

History

The earliest recorded inhabitants of the Western Sahara in historical times were agriculturalists called Bafour. The Bafour were later replaced or absorbed by Berber-language speaking populations that eventually merged in turn with migrating Arab tribes, although the Arabic-speaking majority in the Western Sahara clearly by the historical record descend from Berber tribes that adopted Arabic over time. There may have been some Phoenician contacts in antiquity, but such contacts left few if any long-term traces.

The arrival of Islam in the eighth century played a major role in the development of relationships between the Saharan regions that later became the modern territories of Morocco, Western Sahara, Mauritania, and Algeria, and neighboring regions. Trade developed further and the region became a passage for caravans, especially between Marrakesh and Timbuktu in Mali. In the Middle Ages, the Almohad and Almoravid movements and dynasties both originated from the Saharan regions and were able to control the area.

Toward the late Middle Ages, the Beni Hassan Arab Bedouin tribes invaded the Maghreb, reaching the northern border area of the Sahara in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. Over roughly five centuries, through a complex process of acculturation and mixing seen elsewhere in the Maghreb and North Africa, the indigenous Berber tribes adopted Hassaniya Arabic and a mixed Arab-Berber nomadic culture.

Spanish Province

After an agreement among the European colonial powers at the Berlin Conference in 1884 on the division of spheres of influence in Africa, Spain seized control of the Western Sahara and declared it to be a Spanish protectorate. It conducted a series of wars against the local tribes reminiscent of European colonial adventures of the period elsewhere.

Spanish colonial rule began to unravel with the general wave of decolonizations after World War II, which saw Europeans lose control of North African and sub-Saharan Africa possessions and protectorates. Spanish decolonization began rather late, as internal political and social pressures for it in mainland Spain built up toward the end of Francisco Franco's rule, and in combination with the global trend toward complete decolonization. Spain began rapidly and even chaotically divesting itself of most of its remaining colonial possessions. After initially being violently opposed to decolonization, Spain began to give in and by 1974-1975 issued promises of a referendum on independence. The nascent Polisario Front, a nationalist organization that had begun fighting the Spanish in 1973, had been demanding such a move.

At the same time, Morocco and Mauritania, which had historical claims of sovereignty over the territory, argued that the territory was artificially separated from their territories by the European colonial powers. Algeria viewed these demands with suspicion, influenced by its long-running rivalry with Morocco. After arguing for a process of decolonization guided by the United Nations, the government of Houari Boumédiènne committed itself in 1975 to assisting the Polisario Front, which opposed both Moroccan and Mauritanian claims and demanded full independence.

The International Court of Justice (ICJ) declared in 1975 that the Western Sahara possessed the right of self-determination. On November 6, 1975, the crossing of 350,000 Moroccan civilians into Western Sahara, became known as the Green March.

The Spanish government secretly signed on November 14, 1975, mere days before Franco's death, a tripartite agreement with Morocco and Mauritania as it moved to abandon the territory. Although the accords foresaw a tripartite administration, Morocco and Mauritania each moved to annex the territory, with Morocco taking control of the northern two-thirds of Western Sahara as its Southern Provinces and Mauritania taking control the southern third as Tiris al-Gharbiyya.

Spain terminated its presence in Spanish Sahara within three months. The Moroccan and Mauritanian moves, however, met staunch opposition from the Polisario, which had gained backing from Algeria. In 1979, following Mauritania's withdrawal due to pressures from Polisario, Morocco extended its control to the rest of the territory and gradually contained the guerrillas through setting up an extensive sand berm in the desert to exclude guerrilla fighters. Hostilities ceased in a 1991 cease-fire, overseen by the peacekeeping mission MINURSO, under the terms of the UN's Settlement Plan.

The Referendum stalls

The referendum, originally scheduled for 1992, foresaw giving the local population the option between independence or affirming integration with Morocco, but it quickly stalled. As of 2007, negotiations over terms had not resulted in any substantive action. At the heart of the dispute lies the question of who qualifies to be registered to participate in the referendum, and, since about 2000, Morocco's refusal to accept independence as an option on the ballot while the Polisario insists on its inclusion.

Both sides blame each other for the lack of action. The Polisario has insisted that only the persons found on the 1974 Spanish census lists be allowed to vote, while Morocco asserts the census was flawed and seeks to include members of Sahrawi tribes with recent historical presence in the Spanish Sahara (that is, after the Green March).

By 2001, the process had effectively stalemated and the UN Secretary-General asked the parties for the first time to explore other solutions. Morocco has offered autonomy as an option.

Baker Plan

As personal envoy of the Secretary-General, James Baker visited all sides and produced the document known as the "Baker Plan." This envisioned an autonomous Western Sahara Authority (WSA), to be followed after five years by the referendum. Every person present in the territory would be allowed to vote, regardless of birthplace and with no regard to the Spanish census. It was rejected by both sides, although it was initially derived from a Moroccan proposal. According to Baker's draft, tens of thousands of post-annexation immigrants from Morocco proper (viewed by Polisario as settlers but by Morocco as legitimate inhabitants of the area) would be granted the vote in the Sahrawi independence referendum, and the ballot would be split three ways by the inclusion of an unspecified "autonomy" option, which might have the effect of undermining the independence camp.

In 2003, a new version of the plan was proposed, spelling out the powers of the WSA to make it less reliant on Moroccan devolution. It also provided further details on the referendum process to make it harder to stall or subvert. Commonly known as Baker II, this draft was accepted by Polisario as a "basis of negotiations," to the surprise of many. After that, the draft quickly garnered widespread international support, culminating in the UN Security Council's unanimous endorsement of the plan.

Western Sahara today

Today the Baker II document appears politically redundant, since Baker resigned his post in 2004 following several months of failed attempts to get Morocco to enter into formal negotiations on the plan. The new king, Mohammed VI, opposes any referendum on independence and has said Morocco will never agree to one. Instead, he proposes a self-governing Western Sahara as an autonomous community within Morocco, through an appointed advisory body.

Morocco has repeatedly tried to get Algeria into bilateral negotiations that would define the exact limits of Western Sahara autonomy under Moroccan rule, but only after Morocco's "inalienable right" to the territory was recognized as a precondition to the talks. The Algerian government has consistently refused, claiming it has neither the will nor the right to negotiate on the behalf of Polisario.

Demonstrations and riots by supporters of independence and/or a referendum broke out in May 2005. They were met by police force. Several international human rights organizations expressed concern at what they termed abuse by Moroccan security forces, and a number of Sahrawi activists were jailed.

Morocco declared in February 2006 that it was contemplating a plan for devolving a limited variant of autonomy to the territory but still refused any referendum on independence. The Polisario Front has intermittently threatened to resume fighting, referring to the Moroccan refusal of a referendum as a breach of the cease-fire terms, but most observers seem to consider armed conflict unlikely without a green light from Algeria, which houses the Sahrawis' refugee camps and has been the main military sponsor of the movement.

In April 2007 the government of Morocco suggested that a self-governing entity, through the Royal Advisory Council for Saharan Affairs (CORCAS), govern the territory with some degree of autonomy. The project was presented to the UN Security Council in mid-April 2007. On April 10, U.S. Under Secretary of State Nicholas Burns called the initiative Morocco presented "a serious and credible proposal to provide real autonomy for the Western Sahara."

The stalemate led the UN to ask the parties to enter into direct and unconditional negotiations to reach a mutually accepted political solution. The parties held their first direct negotiations in seven years in New York in June and August 2007. Both sides agreed to more talks but didn't budge on their separate demands. A statement released by the UN mediator, Peter van Walsum, said that the discussions had included confidence-building measures but did not specify them. A UN statement said, "The parties acknowledge that the current status quo is unacceptable and they have committed to continue these negotiations in good faith." But a date and venue for a third session of talks have yet to be determined, the statement said.

Politics

The legal status of the territory and the question of its sovereignty remains unresolved; it is considered a non-self-governed territory by the United Nations.

The Morocco-controlled parts of Western Sahara are divided into several provinces treated as integral parts of the kingdom. The Moroccan government heavily subsidizes the Saharan provinces under its control with cut-rate fuel and related subsidies, to appease nationalist dissent and attract immigrants -or settlers-from loyalist Sahrawi and other communities in Morocco proper.

The exiled government of the self-proclaimed Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) is a form of single-party parliamentary and presidential system, but according to its constitution, this will be changed into a multi-party system at the achievement of independence. It is presently based at the Tindouf refugee camps in Algeria, which it controls. It also claims to control the part of Western Sahara to the east of the Moroccan sand wall. This area is more or less unpopulated and the Moroccan government views it as a no-man's land patrolled by UN troops.

Human rights

Both Morocco and the Polisario accuse each other of violating the human rights of the populations under their control, in the Moroccan-controlled parts of Western Sahara and the Tindouf refugee camps in Algeria, respectively. Morocco and organizations such as France Libertés consider Algeria to be directly responsible for any crimes committed on its territory, and accuse the country of having been directly involved in such violations.

Morocco has been repeatedly criticized by international human rights organizations such as Amnesty International. Polisario has received criticism on its treatment of Moroccan prisoners-of-war, and on its general behavior in the Tindouf refugee camps. A number of former Polisario officials who have defected to Morocco accuse the organization of abuse of human rights and sequestration of the population in Tindouf.

According to the pro-Morocco Moroccan American Center for Policy, Algeria is the primary financial, political, and military supporter of the Polisario Front. Though Libya and countries of the former Soviet bloc historically backed Polisario, their support has decreased since the end of the Cold War.

Sahrawi refugees in the Tindouf camps depend on humanitarian aid donated by several UN organizations as well as international non-governmental organizations. It is widely believed that much of this humanitarian aid never reaches those it is intended to assist because it is sold on the black market in neighboring countries by Polisario. While many in the international community have called for a census and an audit system to ensure the transparent management of the humanitarian aid, to date Polisario has not allowed either a census or independent oversight of its management of humanitarian assistance.

Cuba also supports the Polisario Front and has been accused of kidnapping Sahrawi youth from the refugee camps and sending them to Castro’s Island of Youth, where they are inundated with anti-Western, Marxist-Leninist teachings. The Polisario Front’s objective for the deportation of Sahrawi children is said to be 1) to separate families and 2) to keep pressure on family members who remain in the camps to go along with Polisario leadership so as not to endanger their children’s welfare.

Administrative division

The Western Sahara was partitioned between Morocco and Mauritania in April 1976, with Morocco acquiring the northern two-thirds of the territory. When Mauritania, under pressure from Polisario guerrillas, abandoned all claims to its portion in August 1979, Morocco moved to occupy that sector shortly thereafter and has since asserted administrative control over the whole territory. The official Moroccan government name for Western Sahara is the "Southern Provinces," which indicates Río de Oro and Saguia el-Hamra.

Not under control of the Moroccan government is the area that lies between the sand wall and the actual border with Algeria. The Polisario Front claims to run this as the Free Zone on behalf of the SADR. The area is patrolled by Polisario forces, and access is restricted, even among Sahrawis, due to the harsh climate, the military conflict, and the abundance of land mines.

The Polisario forces (of the Sahrawi People's Liberation Army, or SPLA) in the area are divided into seven "military regions," each controlled by a top commander reporting to the president of the Polisario-proclaimed Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic.

Economy

Aside from its rich phosphate deposits and fishing waters, Western Sahara has few natural resources and lacks sufficient rainfall for most agricultural activities. There is speculation that there may be rich off-shore oil and natural gas fields, but the debate persists as to whether these resources can be profitably exploited, and if this would be legally permitted due to the ambiguous status of Western Sahara.

Western Sahara's economy is centered around nomadic herding, fishing, and phosphate mining. Most food for the urban population is imported. All trade and other economic activities are controlled by the Moroccan government. The government has encouraged citizens to relocate to the territory by giving subsidies and price controls on basic goods. These heavy subsidies have created a state-dominated economy in the Moroccan-controlled parts of Western Sahara, with the Moroccan government as the single biggest employer. Incomes in Western Sahara are substantially below the Moroccan level.

Morocco and the EU signed a four-year agreement in July 2006 allowing European vessels to fish off the coast of Morocco, including the disputed waters off the coast of Western Sahara.

After reasonably exploitable oil fields were located in neighboring Mauritania, speculation intensified on the possibility of major oil resources being located off the coast of Western Sahara. Despite the fact that findings remain inconclusive, both Morocco and Polisario have made deals with oil and gas exploration companies. In 2002, the head of the UN's Office of Legal Affairs issued a legal opinion on the matter stating that while "exploration" of the area was permitted, "exploitation" was not.

Demographics

The indigenous population of Western Sahara is known as Sahrawis. These are Hassaniya-speaking tribes of mixed Arab-Berber heritage, effectively continuations of the tribal groupings of Hassaniya-speaking Moorish tribes extending south into Mauritania and north into Morocco as well as east into Algeria. The Sahrawis are traditionally nomadic bedouins, and can be found in all surrounding countries.

As of July 2004, an estimated 267,405 people (excluding the Moroccan army of some 160,000) live in the Moroccan-controlled parts of Western Sahara. Morocco brought in large numbers of settlers in anticipation of a UN-administered referendum on independence. While many of them are from Sahrawi tribal groups living in southern Morocco, others are non-Sahrawi Moroccans from other regions. The settler population is today thought to outnumber the indigenous Western Sahara Sahrawis. The precise size and composition of the population is subject to political controversy.

The Polisario-controlled parts of Western Sahara are barren and have no resident population, but they are traveled by small numbers of Sahrawis herding camels, going back and forth between the Tindouf area and Mauritania. However, the presence of mines scattered throughout the territory by both the Polisario and the Moroccan army makes it a dangerous way of life.

The Spanish census and MINURSO

A 1974 Spanish census claimed there were some 74,000 Sahrawis in the area at the time (in addition to approximately 20,000 Spanish residents), but this number is likely to be on the low side, due to the difficulty in counting a nomad people, even if Sahrawis were by the mid-1970s mostly urbanized.

In 1999 the United Nations' MINURSO mission announced that it had identified 86,425 eligible voters for the referendum that was supposed to be held under the 1991 settlement plan. By "eligible voter" the UN referred to any Sahrawi over 18 years of age that was part of the Spanish census or could prove his/her descent from someone who was. These 86,425 Sahrawis were dispersed between Moroccan-controlled Western Sahara and the refugee camps in Algeria, with smaller numbers in Mauritania and other places of exile. These numbers cover only Sahrawis "indigenous" to the Western Sahara during the Spanish colonial period, not the total number of "ethnic" Sahrawis (i.e, members of Sahrawi tribal groupings), who also extend into Mauritania, Morocco, and Algeria.

The Polisario declares the number of Sahrawis living in the Tindouf refugee camps in Algeria to be approximately 155,000. Morocco disputes this number, saying it is exaggerated for political reasons and to attract more foreign aid. The UN uses a number of 90,000 "most vulnerable" refugees as the basis for its food aid program.

Status of refugees

Sahrawi refugees began arriving in Algeria in 1976 after Spain withdrew from the Western Sahara and fighting broke out over its control. Most of the Sahrawi refugees have been living for more than 30 years in the desert regions of Tindouf. Some of the Sahrawis stayed in the Western Sahara, however, and families remain separated.

In September 2007, the UN refugee agency said it feared that a lack of funding could bring a halt to confidence-building measures connecting Sahrawi refugees in Algeria and their relatives in the Western Sahara. In January 2007, UNHCR had appealed for nearly US $3.5 million to continue the family visits and telephone services initiated in 2004. "But with only a little over half of the appeal funded so far, the whole operation risks being stopped next month [October 2007]," the UNHCR said.

A total of 154 visits have taken place involving 4,255 people – mainly women. An additional 14,726 people are waiting to take part in the program. Almost 80,000 calls have been placed in four refugee camps in Algeria with telephone centers.

Culture

The major ethnic group of the Western Sahara are the Sahrawis, a nomadic or bedouin tribal or ethnic group speaking a Hassaniya dialect of Arabic, also spoken in much of Mauritania. They are of mixed Arab-Berber descent but claim descent from the Beni Hassan, a Yemeni tribe that is supposed to have migrated across the desert in the eleventh century.

Physically indistinguishable from the Hassaniya-speaking Moors of Mauritania, the Sahrawi people differ from their neighbors partly due to different tribal affiliations (as tribal confederations cut across present modern boundaries) and partly as a consequence of their exposure to Spanish colonial domination. The surrounding territories were generally under French colonial rule.

Like other neighboring Saharan Bedouin and Hassaniya groups, the Sahrawis are Muslims of the Sunni sect and the Maliki law school. Local religious custom is, like other Saharan groups, heavily influenced by pre-Islamic Berber and African practices, and differs substantially from urban practices. For example, Sahrawi Islam has traditionally functioned without mosques in the normal sense of the word, in an adaptation to nomadic life.

The originally clan- and tribe-based society underwent a massive social upheaval in 1975, when a part of the population settled in the refugee camps of Tindouf, Algeria. Families were broken up by the flight.

The Moroccan government has invested in the social and economic development of the region of Western Sahara it controls, with special emphasis on education, modernization, and infrastructure. Laayoune (El-Aaiun) in particular has been the target of heavy government investment and has grown rapidly. Several thousand Sahrawis study in Moroccan universities. Literacy rates are about 50 percent of the population.

Notes

- ↑ "Regions and Territories: Western Sahara", BBC News, 9 December 2011. Retrieved January 17, 2012.

- ↑ "Q&A: Western Sahara Clashes", BBC News, 8 November 2010. Retrieved January 17, 2012.

- ↑ Jensen, Erik (2005). Western Sahara: Anatomy Of A Stalemate, International Peace Academy Occasional Paper Series. Lynne Rienner Publishers. ISBN 1588263053. Retrieved January 17, 2012.

- ↑ Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division (2009). World Population Prospects, Table A.1. Retrieved January 17, 2012.

- ↑ Ahmed R. Benchemsi and Mehdi Sekkouri Alaoui. Au cœur du polisario. Telquel. Retrieved January 17, 2012. "Tout cela se paie en dinars algériens"

Sources and Further Reading

- Hodges, Tony. 1983. Western Sahara: the roots of a desert war. Westport, CT: L. Hill. ISBN 9780882081519

- Jensen, Erik. 2005. Western Sahara: anatomy of a stalemate. International Peace Academy occasional paper series. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers. ISBN 1588263053

- Mayhew, Bradley, and Jan Dodd. 2003. Morocco. Melbourne: Lonely Planet. ISBN 1740593618 and ISBN 9781740593618

- Pazzanita, Anthony G., and Tony Hodges. 1994. Historical dictionary of Western Sahara. African historical dictionaries, no. 55. Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0810826615

- Radu, Michael. September, 2007. Struggle in the Sandbox: Western Sahara and the "International Community". Foreign Policy Research Institute. Retrieved September 26, 2007.

- Shelley, Toby. 2004. End game in the Western Sahara: what future for Africa's last colony? London: Zed. ISBN 1842773410

External links

All links retrieved May 4, 2023.

- British Broadcasting Corporation. Regions and territories: Western Sahara.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.