Bedouin

Bedouin, derived from the Arabic badawī بدوي, a generic name for a desert-dweller, is a term generally applied to Arab nomadic pastoralist groups, who are found throughout most of the desert belt extending from the Atlantic coast of the Sahara via the Western Desert, Sinai, and Negev to the eastern coast of the Arabian desert. It is occasionally used to refer to non-Arab groups as well, notably the Beja of the African coast of the Red Sea. They constitute only a small portion of the total population of the Middle East although the area they inhabit is large due to their nomadic, or former nomadic lifestyle. Reductions in their grazing ranges and increases in their population, as well as the changes brought about by the discovery and development of oil fields in the region, have led many Bedouin to adopt the modern urban, sedentary lifestyle with its accompanying attractions of material prosperity.

History

Bedouins spread out over the pastures of the Arabian Peninsula in the centuries C.E., and are descendants from the first settlers of the Southwestern Arabia (Yemen), and the second settlers of North-Central Arabia, claimed descendants of Ishmael, who are called the Qayis. The rivalry between both groups of the Bedouins has raged many bloody battles over the centuries.

The fertile crescent of Arabia was known for its lucrative import trade with southern Africa, which included items such as exotic herbs and spices, gold, ivory, and livestock. The oases of the Bedouins were often mobile markets of trade, as their lifestyle involved frequent migrating of the herds in search of greener pastures. The Bedouins were often ruthless raiders of established desert communities, in a never-ending conquest for plunder and material wealth. Equally, they practiced generous hospitality, and valued the virtue of chastity in their women, who were their ambassadors of generosity and hospitality. They followed their code of honor religiously, governed by tribal chieftains, or Sheikhs, who were elected by tribal elders.

In the first few centuries C.E., many Bedouin were converted to Christianity and Judaism, and many Bedouin tribes fell to Roman slavery. By the turn of the seventh century, most Bedouins had been converted to Islam.

The incessant warring caused great conflict and discontent among the tribal leaders, and as such they decided to branch out in their travels as far as Syria, Palestine, Egypt, Iraq, and Persia, often amazed at the excessive wealth of the civilizations which they encountered throughout Arabia. However, when the Mongols took the city of Baghdad in 1258 C.E., the Bedouin people were subjected to accepting Ottoman presence and authority.

The nineteenth century proved pivotal in the history of the Bedouins, as the British pushed through on their way to India. Some Bedouin under British rule began to transition to a semi-nomadic lifestyle. By the 1930s, the oil fields had been established and farmed by Americans and British, which brought gratuitous wealth to the Arabian empire, bringing desert people into a modern world of lavish comforts and technology. In the 1950s and 1960s, large numbers of Bedouin throughout the Middle East started to leave the traditional, nomadic life to settle in the cities. The traditional nomadic Bedouin became an endangered species in terms of survival, as contemporary commerce rolled into Arabia.

Traditional Bedouin culture

The Bedouins were traditionally divided into related tribes. These tribes were organized on several levels—a widely-quoted Bedouin saying is:

I against my brothers, I and my brothers against my cousins, I and my brothers and my cousins against the world

The individual family unit (known as a tent or bayt) typically consisted of three or four adults (a married couple plus siblings or parents) and any number of children, and would focus on semi-nomadic pastoralism, migrating throughout the year following water and plant resources. Royal Tribes traditionally herded camels, whilst others herded sheep, and goats.

When resources were plentiful, several tents would travel together as a goum. These groups were sometimes linked by patriarchical lineage but just as likely linked by marriage (new wives were especially likely to have male relatives join them), acquaintance or even no clearly defined relation but a simple shared membership in the tribe.

The next scale of interactions inside tribal groups was the ibn amm or descent group, commonly of three or five generations. These were often linked to goums, but whereas a goum would generally consist of people all with the same herd type, descent groups were frequently split up over several economic activities (allowing a degree of risk-management: should one group of members of a descent group suffer economically, the other members should be able to support them). Whilst the phrase descent group suggest purely a patriarchal arrangement, in reality these groups were fluid and adapted their genealogies to take in new members.

The largest scale of tribal interactions is obviously the tribe as a whole, led by a Sheikh. The tribe often claims descent from one common ancestor—as above, this appears patrilineal but in reality new groups could have genealogies invented to tie them in to this ancestor. The tribal level is the level that mediated between the Bedouin and the outside governments and organizations.

Men and women are equal partners in Bedouin society: "men can get nowhere without a woman and women cannot be anyone without a man."[1] The apparent inequality between the status of men and women is due to their different roles—men are involved in public activities and women stay in the private sphere. While a woman's status is determined by her husband, the woman holds her husband's honor in her hands—she is responsible for their tent, their hospitality to guests, all the work of maintaining the household and the herds, and raising the children. Despite the apparent relegation of Bedu women to a "second class" status where they are not seen or active in public life, in fact this is for their protection as extremely valuable persons in the society. Bedu men are often violent, but such violence is kept separate from the private side of life and thus keeps the women safe.[1]

The Bedouin people could be as just as hospitable as they were warring. If a desert traveler touched their tent pole, they were obligated to welcome and invite this guest, along with his entourage and animals for up to three days without any payment. Status of the guest was indicated by the mare's bridle being hung from the tent's central pole, and in this way, tribes that were often at war would meet and, with great hospitality, break bread and share stories of their most noteworthy horses.

The Bedouin people revere their horses as westerners revere their children. Horses are considered a gift from Allah, and any mixture of foreign blood from the mountains or the cities surrounding the desert was strictly forbidden, and considered an abomination. The proud Bedouin stoically disdain most breeds other than the long line of stout Arabian horses.

The Arabian horse was generally a weapon of war, and as such a well-mounted Bedouin could attack enemy tribes and plunder their livestock, adding to their own material wealth. These bold raids depended on a quick getaway with reliable horses. Mares were more practical than stallions, with their lighter weight and agility. They were trained not to nicker to the enemy tribe's horses, giving away their owner's approach. These stoic animals often displayed worthy exhibits of courage, taking spear thrusts in the side without giving any ground.

Systems of justice

Bedouin systems of justice are as varied as the Bedouin tribes themselves. A number of these systems date from pre-Islamic times, and hence do not follow the Sharia. However, many of these systems are falling into disuse as more and more Bedouins follow the Sharia or national penal codes for dispensing justice. Bedouin honor codes are one of three Bedouin aspects of ethics that contain significant amounts of pre-Islamic customs: namely those of hospitality, courage, and honor.[2]

There are separate honor codes for men (sharif) and women (ird).[2] Bedouin customs relating to preservation of honor, along with those relating to hospitality and bravery, date to pre-Islamic times. [2] In many Bedouin courts, women often do not have a say as defendant or witness, [3] and decisions are taken by village elders.

Ird is the Bedouin honor code for women. A woman is born with her ird intact, but sexual transgression could take her ird away. Ird is different from virginity, as it is emotional/conceptual. Once lost, ird cannot be regained.[2]

Sharaf is the general Bedouin honor code for men. It can be acquired, augmented, lost, and regained. Sharaf involves protection of the ird of the women of the family, protection of property, maintenance of the honor of the tribe, and protection of the village (if the tribe has settled down).[2]

Hospitality (diyafa) is a virtue closely linked to Sharaf. If required, even an enemy must be given shelter and fed for some days. Poverty does not exempt one from one's duties in this regard. Generosity is a related virtue, and in many Bedouin societies gifts must be offered and cannot be declined. The destitute are looked after by the community, and tithing is mandatory in many Bedouin societies.[4]

Bravery (hamasa) is also closely linked to Sharaf. Bravery indicated the willingness to defend one's tribe for the purpose of tribal solidarity and balance (assahiya). It is closely related to manliness (muruwa). Bravery usually entails the ability to withstand pain, including male circumcision.[4]

Members of a single tribe usually follow the same system of justice, and often claim descent from a single common ancestor. Closely related tribes may also follow similar systems of justice, and may even have common arbitrating courts. Jurists in Arab states have often referred to Bedouin customs for precedence.[3] In smaller Bedouin tribes, conflict resolution can be as informal as talks between families of the two parties. However, social protocols of conflict resolution are in place for the larger tribes.

Bedouins do not have the concept of incarceration being a nomadic tribe. Petty crimes, and some major ones, are typically settled by fines and grievous crimes by physical pain and bodily harm, or capital punishment. Bedouin tribes are typically held responsible for the action of their members, hence if an accused fails to pay a fine, the accused's tribe is expected to pay—upon which the accused, or the accused's family, becomes obligated to the tribe.

Trials by ordeal are used by the Bedouin to decide on the gravest of crimes. Authorities to hold such trials and judge them are granted to few, and that too on a hereditary basis. The most well-known of the trials by ordeal is the Bisha'a or Bisha. This is a custom practiced among the Bedouin of the Judea, Negev, and Sinai. It is also practiced and is said to have originated among some Bedouin tribes of Saudi Arabia.

The Bisha'a, or trial by fire, is a protocol for lie detection, and is enacted only in the harshest of civil or criminal violations, like a blood feud—usually in the absence of witnesses. It entails having the accused lick a hot metal spoon and subsequently rinse the mouth with water. If the tongue shows signs of a burn or a scar the accused is taken to be guilty of lying.[5] [6]

The right to perform Bisha'a is granted only to the Mubesha, and this right is passed on from father to son, along paternal lineages. The Mubesha hears the account of the dispute before performing the ceremony, and is also responsible for pressing the metal spoon against the tongue of the person undergoing the Bisha'a. There are only a few practitioners of the Bisha'a in Bedouin society. A single Mubesha might arbitrate over several tribes and large geographical areas, like the Mubesha of Abu Sultan in Egypt.

Music

Bedouin music is highly syncopated and generally unaccompanied. Because songs are mostly a cappella, the vocals and lyrics are the most integral part of Bedouin music. Poetry (al-shi'ir al-nabatî) is a part of many songs. Other types include taghrud (or hidâ' ), the songs of camel-drivers, and dance songs of preparation for war (ayyâla, or 'arda).

Yamania songs are a type of Bedouin music that comes from the fishermen of the Arabian Peninsula. These songs are related to exorcism and are accompanied by a five-stringed lyre called the simsimiyya.

Among the popular singers to use elements of Bedouin music in their style is the Israeli Yair Dalal.

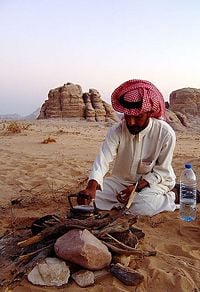

Traditional Clothing

The traditional Bedouin "dress" is a thobe (also spelled thawb which is the standard Arabic word for a "garment"). These garments are loose and require little maintenance; very practical for the nomadic lifestyle.

Men usually wear a long white thobe made of cotton, with a sleeveless coat on top; women wear blue or black thobes with blue or red embroidered decoration. They also wear a jacket.

Married Bedouin women wear a scarf folded into a headband covering the forehead. Unmarried women wear it unfolded. Women in some areas are veiled; others not. They wear a variety of jewelry that may include protective elements.

Contemporary Bedouin

Starting in the 1950s and 1960s, many Bedouin started to leave the traditional, nomadic life to work and live in the cities of the Middle East, especially as grazing ranges have shrunk and population levels have grown. In Syria, for example, the Bedouin way of life effectively ended during a severe drought from 1958 to 1961, which forced many Bedouin to give up herding for standard jobs. Similarly, government policies in Egypt, oil production in Libya and the Gulf, and a desire for improved standards of living have had the effect that most Bedouin are now settled citizens of various nations, rather than nomadic herders and farmers.

Government policies on settlement are generally put in place through a desire to provide services (schools, health care, law enforcement and so on). This is considerable easier for a fixed population than for semi-nomadic pastoralists.[7]

Notable Bedouin tribes

There are a number of Bedouin tribes, but the total population is often difficult to determine, especially as many Bedouin have ceased to lead nomadic or semi-nomadic lifestyles (see above) and joined the general population. Some of the tribes and their historical population:

- Aniza, the largest bedouin tribe, estimated at about 700,000 members (including the Rwala), live in northern Saudi Arabia, western Iraq, and the Syrian steppe.

- Rwala, a large clan from the Aniza tribe, live in Saudi Arabia, but extend through Jordan into Syria and Iraq, in the 1970s, according to Lancaster, there were 250,000-500,000 Rwala

- Howeitat in Wadi Araba, and Wadi Rum, Jordan

- Beni Sakhr in Syria and Jordan

- Al Murrah in Saudi Arabia

- Bani Hajir (AlHajri) in Saudi Arabia and the eastern Gulf States

- Bani Khalid in Jordan, Israel, Palestinian Territories, and Syria, also in the eastern Arabian Peninsula

- Shammar in Saudi Arabia, central, and western Iraq, Shammar is the second largest bedouin tribe.

- Mutair, live in the Nejd plateau, also, many small families from the Mutair tribe have lived in the Gulf States

- Al-Ajman, eastern Saudi Arabia and the Gulf States

- Sudair, southern Nejd, around the Sudair region of Saudi Arabia

- Al-Duwasir, southern Riyadh, and Kuwait

- Subai'a, central Nejd, and Kuwait

- Harb, a large tribe, living around Mecca

- Juhayna, a large tribe, many of its warriors were recruited as mercenaries during WWI by Prince Faisal. It surrounds the area of Mecca, and extends to Southern Medina

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 William Lancaster, The Rwala Bedouin Today (Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press, 1997, ISBN 978-0881339437).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Raphael Patai, The Arab Mind (Hatherleigh Press, 2007, ISBN 978-1578262458).

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 G.W. Murray, Sons of Ishmael: A Study of the Egyptian Bedouin. (London: Routledge, 1935)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Martha Blake, The Ghinnawa: How Bedouin Women's' Poetry Supplements Social Expression Retrieved September 25, 2007.

- ↑ John B. Glubb. Some Bedouin Customs and Traditions Jordan Jubilee Retrieved September 25, 2007.

- ↑ A. Al-Krenawi, and J. R. Graham, "Conflict resolution through a traditional ritual among the Bedouin Arabs of the Negev" Ethnology 38 (1999): 163-174, Retrieved September 25, 2007.

- ↑ Dawn Chatty, From Camel to Truck: The Bedouin in the Modern World (Vantage Press, 1986, ISBN 978-0533064847)

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Abu-Lughod, Lila. Veiled Sentiments: Honor and Poetry in a Bedouin Society. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2000. ISBN 0520224736

- Altorki, Soraya, and Donald P. Cole. Bedouin, Settlers and Holiday-Makers: Egypt's Changing Northwest Coast. American University in Cairo Press, 1998. ISBN 9774244842

- Bailey, Clinton. A Culture of Desert Survival: Bedouin Proverbs from Sinai and the Negev. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300098440

- Chatty, Dawn. From Camel to Truck. The Bedouin in the Modern World. New York, NY: Vantage Press, 1986. ISBN 978-0533064847

- Chatty, Dawn. Mobile Pastoralists. New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 1996. ISBN 978-0231105491

- Cole, Donald P. "Where have the Bedouin gone?." Anthropological Quarterly 76(2) (Spring 2003): 235 Washington.

- Gardner, Ann. "At Home in South Sinai." Nomadic Peoples 4(2) (2000): 48-67.

- Jabbur, Jibrail S. The Bedouins and the Desert: Aspects of Nomadic Life in the Arab East. State University of New York Press, 1995. ISBN 0791428516

- Kennett, Austin. Bedouin Justice: Law and Custom Among the Egyptian Bedouin. Cambridge University Press, 2011 (original 1925). ISBN 978-0521230834

- Lancaster, William. The Rwala Bedouin Today. Waveland Press, 1997. ISBN 0881339431

- Patai, Raphael. The Arab Mind. Hatherleigh Press, 2007. ISBN 978-1578262458

- Peters, Emrys L. The Bedouin of Cyrenaica: Studies in Personal and Corporate Power. Cambridge University Press, 2007. ISBN 0521040469

- Thesiger, Wilfred. Arabian Sands. Penguin paperback, 1959. ISBN 0140095144

External links

All links retrieved September 26, 2023.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Bedouin history

- Bedouin_music history

- Bisha'a history

- Honor_codes_of_the_Bedouin history

- Bedouin_systems_of_justice history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.