Neocolonialism

Neocolonialism is a term used by post-colonial critics of developed countries' involvement in the developing world. Critics of neocolonialism argue that existing or past international economics arrangements created by former colonial powers were, or are, used to maintain control of their former colonies and dependencies after the colonial independence movements of the post-World War II period. The term Neocolonialism can combine a critique of current actual colonialism (where some states continue administrating foreign territories and their populations in violation of United Nations resolutions[1]) and a critique of modern capitalist businesses involvement in nations which were former colonies. Critics of neocolonialism contend that private, foreign business companies continue to exploit the resources of post-colonial peoples, and that this economic control inherent to neocolonialism is akin to the classical, European colonialism practiced from the sixteenth to the twentieth centuries.

In broader usage, especially in Latin America, Neocolonialism may simply refer to involvement of powerful countries in the affairs of less powerful countries. In this sense, Neocolonialism implies a form of contemporary, economic Imperialism: That powerful nations behave like colonial powers, and that this behavior is likened to colonialism in a post-colonial world. Neoimperialism might better describe what the term neocolonialism is intended to mean. However, the international system, beginning with the veto of the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council can be understood as perpetuating the domination of powerful, rich nations over less powerful states. Loans by international banking institutions and even development, aid and relief efforts have been criticized as perpetuating dependency by failing to address the causes of poverty. Neocolonialism critiques how some states treat other states but also raises questions about whether the nation state is, as many argue, the ultimate form of political organization. Only when humanity, it can be argued, tackles issues that confront all people globally will global solutions become possible. For some people of religious faith, the end goal of human history is the creation of a single nation under God in which all the cultures, faiths and races of the world are respected, honored and universal peace and justice is achieved.

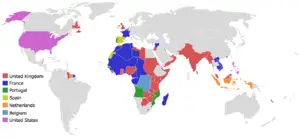

Neocolonialism charges against former colonial powers

| ââ 0.950 + ââ 0.900-0.949 ââ 0.850-0.899 ââ 0.800-0.849ââ 0.750-0.799 | ââ 0.700-0.749 ââ 0.650-0.699 ââ 0.600-0.649 ââ 0.550-0.599 ââ 0.500-0.549 | ââ 0.450-0.499 ââ 0.400-0.449 ââ 0.350-0.399 ââ 0.300-0.349 ââ under 0.300 ââ n/a |

The term neocolonialism first saw widespread use, particularly in reference to Africa, soon after the process of decolonization which followed a struggle by many national independence movements in the colonies following World War II. Upon gaining independence, some national leaders and opposition groups argued that their countries were being subjected to a new form of colonialism, waged by the former colonial powers and other developed nations. Kwame Nkrumah, who in 1957 became leader of newly independent Ghana, expounded this idea in his Neo-Colonialism: The Last Stage of Imperialism, in 1965.[2]

Pan-African and nonaligned movements

The term "neocolonialism" was popularized in the wake of decolonialization, largely through the activities of scholars and leaders from the newly independent states of Africa and the Pan-Africanist movement. Many of these leaders came together with those of other post colonial states at the Bandung Conference of 1955, leading to the formation of the Non-Aligned Movement. The All-African Peoples' Conference (AAPC) meetings of the late 1950s and early 1960s spread this critique of neocolonialism. Their Tunis conference of 1960 and Cairo conference of 1961 specified their opposition to what they labeled neocolonialism, singling out the French Community of independent states organized by the former colonial power. In its four page Resolution on Neocolonialism is cited as a landmark for having presented a collectively arrived at definition of neocolonialism and a description of its main features.[3] Throughout the Cold War, the Non-Aligned Movement, as well as organizations like the Organization of Solidarity with the People of Asia, Africa and Latin America defined neocolonialism as a primary collective enemy of these independent states.

Denunciations of neocolonialism also became popular with some national independence movements while they were still waging anti-colonial armed struggle. During the 1970s, in the Portuguese colonies of Mozambique and Angola for example, the rhetoric espoused by the Marxist movements FRELIMO and MPLA, which were to eventually assume power upon those nations' independence, rejected both traditional colonialism and neocolonialism.

Paternalistic neocolonialism

The term paternalistic neocolonialism involves the belief held by a neo-colonial power that their colonial subjects benefit from their occupation. Critics of neocolonialism, arguing that this is both exploitive and racist, contend this is merely a justification for continued political hegemony and economic exploitation of past colonies, and that such justifications are the modern reformulation of the Civilizing mission concepts of the nineteenth century.

Françafrique

The classic example used to define modern neocolonialism is Françafrique: A term that refers to the continuing close relationship between France and some leaders of its former African colonies. It was first used by president of the Côte d'Ivoire Félix Houphouët-Boigny, who appears to have used it in a positive sense, to refer to good relations between France and Africa, but it was subsequently borrowed by critics of this close (and they would say) unbalanced relationship. Jacques Foccart, who from 1960 was chief of staff for African matters for president Charles de Gaulle (1958â69) and then Georges Pompidou (1969-1974), is claimed to be the leading exponent of Françafrique.[4] The term was coined by François-Xavier Verschave as the title of his criticism of French policies in Africa: La Françafrique, The longest Scandal of the Republic.[5]

In 1972, Mongo Beti, a writer in exile from Cameroon published Main basse sur le Cameroun, autopsie d'une décolonisation ("Cruel hand on Cameroon, autopsy of a decolonization"), a critical history of recent Cameroon, which asserted that Cameroon and other colonies remained under French control in all but name, and that the post-independence political elites had actively fostered this continued dependence.[6]

Verschave, Beti, and others point to a forty year post independence relationship with nations of the former African colonies, whereby French troops maintain forces on the ground (often used by friendly African leaders to quell revolts) and French corporations maintain monopolies on foreign investment (usually in the form of extraction of natural resources). French troops in Africa were (and it is argued, still are) often involved in coup d'états resulting in a regime acting in the interests of France but against its country's own interests.

Those leaders closest to France (particularly during the Cold War, are presented in this critique as agents of continued French control in Africa. Those most often mentioned are Omar Bongo, president of Gabon, Félix Houphouët-Boigny, former president of Côte d'Ivoire, Gnassingbé Eyadéma, former president of Togo, Denis Sassou-Nguesso, of the Republic of the Congo, Idriss Déby, president of Chad, and Hamani Diori former president of Niger.

Francophonie

The French Community and the later Organisation Internationale de la Francophonie are defined by critics as agents of French neocolonial influence, especially in Africa. While the main thrust of this claim is that the Francophonie organization is a front for French dominance of post-colonial nations, the relation with the French language is often more complex. Algerian intellectual Kateb Yacine wrote in 1966 that "Francophony is a neocolonial political machine, which only perpetuates our alienation, but the usage of French language does not mean that one is an agent of a foreign power, and I write in French to tell the French that I am not French."

Belgian Congo

After a hastened decolonization process of the Belgian Congo, Belgium continued to control, through The Société Générale de Belgique, roughly 70 percent of the Congolese economy following the decolonization process. The most contested part was in the province of Katanga where the Union Minière du Haut Katanga, part of the Société, had control over the mineral and resource rich province. After a failed attempt to nationalize the mining industry in the 1960s, it was reopened to foreign investment.

United Kingdom

Critics of British relations with its former African colonies point out that the United Kingdom viewed itself as a "civilizing force" bringing "progress" and modernization to its colonies. This mindset, they argue, has enabled continued military and economic dominance in some of its former colonies, and has been seen again following British intervention in Sierra Leone. The outbreak of wars between rival tribal factions, such as the Nigerian Civil War and the frequency of coups on the one hand reinforces for neocolonialists that colonial rule was more effective in maintaining civil order and that the colonies were not ready for self-rule. On the other hand, former colonists point out that their borders were artificially drawn from Europe, that under colonial rule democratic institutions did not exist thus post-colonial leaders lack experience, while many economic problems result from centuries of exploitation. For example, raw materials were mined and exported, single, cash crops were cultivated and infrastructure built served the needs of the colonial power, not the colonized territory. On the one hand, the smaller political units that preexisted colonial rule did not have always prevent conflict. On the other, people in one polity did not necessarily regard the resources of those in another as rightfully theirs. When these polities became combined within an artificial national state, people in an under-resourced region became jealous of those who lived in a better resources area. For example, the Nigerian North might not have been envious of the oil-reserves found in the South.

Neocolonialism as economic dominance

In broader usage the charge of Neocolonialism has been leveled at powerful countries and transnational economic institutions who involve themselves the affairs of less powerful countries. In this sense, "Neo"colonialism implies a form of contemporary, economic Imperialism: That powerful nations behave like colonial powers, and that this behavior is likened to colonialism in a post-colonial world.

In lieu of direct military-political control, neocolonialist powers are said to employ financial, and trade policies to dominate less powerful countries. Those who subscribe to the concept maintain this amounts to a de facto control over less powerful nations.

Both previous colonizing states and other powerful economic states maintain a continuing presence in the economies of former colonies, especially where it concerns raw materials. Stronger nations are thus charged with interfering in the governance and economics of weaker nations to maintain the flow of such material, at prices and under conditions which unduly benefit developed nations and trans-national corporations.

Dependency theory

The concept of economic neocolonialism was given a theoretical basis, in part, through the work of Dependency theory. This body of social science theories, both from developed and developing nations, is predicated on the notion that there is a center of wealthy states and a periphery of poor, underdeveloped states. Resources are extracted from the periphery and flow towards the states at the center in order to sustain their economic growth and wealth. A central concept is that the poverty of the countries in the periphery is the result of the manner of their integration of the "world system," a view to be contrasted with that of free market economists, who argue that such states are progressing on a path to full integration. This theory is based on the Marxist analysis of inequalities within the world system, dependency argues that underdevelopment of the Global South is a direct result of the development in the Global North.

The basis of much of this Marxist theory is in theories of the "semi-colony," which date back to the late nineteenth century.[7]

Proponents of such theories include Federico Brito Figueroa a Venezuelan historian who has written widely on the socioeconomic underpinnings of both colonialism and neocolonialism. Brito's works and theories strongly influenced the thinking of current Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez.

The Cold War

In the late twentieth century conflict between the Soviet Union and the United States, the charge of Neocolonialism was often aimed at Western (and less often, Soviet) involvement in the affairs of developing nations. Proxy Wars, many in former colonized nations, were funded by both sides throughout this period. Cuba, the Soviet bloc, Egypt under Nasser, as well as some governments of newly independent African states, charged the United States with supporting regimes which they felt did not represent the will of their peoples, and by means both covert and overt, toppling governments which rejected the United States. The Tricontinental Conference, chaired by Moroccan politician Mehdi Ben Barka was one such organization. Roughly designated as part of the Third World movement, it supported revolutionary anti-colonial action in various states, provoking the anger of the United States and France. Ben Barka himself led what was called the Commission on Neocolonialism of the organization, which focused both on the involvement of former colonial powers in post colonial states, but also contended that the United States, as leader of the capitalist world, with the primary Neocolonialist power. Much speculation remains about Ben Barka disappearance in 1965. The Tricontinental Conference was succeeded organization such as Cuba's OSPAAAL (Spanish for "Organization for Solidarity with the People of Africa, Asia and Latin America"). Such organizations, feeding into what became the Non-aligned Movement of the 1960s and 70s used Neocolonialism, in much the same way as Marxist dependency theory intellectuals did, to encompass all capitalist nations, and most especially the United States. This usage remains popular on the political left today, most especially in Latin America.

Multinational corporations

Critics of neocolonialism also attempt to demonstrate that investment by multinational corporations enriches few in underdeveloped countries, and causes humanitarian, environmental and ecological devastation to the populations which inhabit the neocolonies. This, it is argued, results in unsustainable development and perpetual underdevelopment; a dependency which cultivates those countries as reservoirs of cheap labor and raw materials, while restricting their access to advanced production techniques to develop their own economies. Some point out that large multi (or trans-national) companies are more powerful and wealthy than many states. They consider their own interests over those of the states in which they work. For example, cheap labor or cheap resources may attract a company to build a plant in a certain state. It remains in their interest that labor remains cheap, which is certainly not in the interests of those who provide the labor. Others argue that aspects of trans-national business means that the viability of each economy in which a company operates is a significant concern and that in determining policy companies have to consider how this will impact across the globe, not only in a single context. Share-holders, too, are spread across the globe and have a say in policy.

Proponents of ties which critics have labeled neocolonial thus argue that, while the First World does profit from cheap labor and raw materials in underdeveloped nations, ultimately, it does serve as a positive modernizing force for development in the Third World.

International financial institutions

Critics of neocolonialism portray the choice to grant or to refuse granting loans (particularly those financing otherwise unpayable Third World debt), especially by international financial institutions such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and the World Bank (WB), as a decisive form of control. They argue that in order to qualify for these loans, and other forms of economic aid, weaker nations are forced to take certain steps favorable to the financial interests of the IMF and World Bank but detrimental to their own economies. These structural adjustments have the effect of increasing rather than alleviating poverty within the nation.

Some critics emphasize that neocolonialism allows certain cartels of states, such as the World Bank, to control and exploit usually lesser developed countries (LDCs) by fostering debt. In effect, third world governments give concessions and monopolies to foreign corporations in return for consolidation of power and monetary bribes. In most cases, much of the money loaned to these LDCs is returned to the favored foreign corporations. Thus, these foreign loans are in effect subsidies to corporations of the loaning state's. This collusion is sometimes referred to as the corporatocracy. Organizations accused of participating in neo-imperialism include the World Bank, World Trade Organization and Group of Eight, and the World Economic Forum. Various "first world" states, notably the United States, are said to be involved, as described in Confessions of an Economic Hitman by John Perkins. By convention, the United States nominates the head of the World Bank while the Europeans nominate the head of the IMF.

Neocolonialism allegations against the IMF

Those who argue that neocolonialism historically supplemented (and later supplanted) colonialism, point to the fact that Africa today pays more money every year in debt service payments to the IMF and World Bank than it receives in loans from them, thereby often depriving the inhabitants of those countries from actual necessities. This dependency, they maintain, allows the IMF and World Bank to impose Structural Adjustment Plans upon these nations. Adjustments largely consisting of privatization programs which they say result in deteriorating health, education, an inability to develop infrastructure, and in general, lower living standards.

They also point to recent statements made by United Nations Secretary-General's Special Economic Adviser, Dr. Jeffrey Sachs, who heatedly demanded that the entire African debt (approximately $200 billion) be forgiven outright and recommended that African nations simply stop paying if the World Bank and IMF do not reciprocate:

- The time has come to end this charade. The debts are unaffordable. If they won't cancel the debts I would suggest obstruction; you do it yourselves. Africa should say: "Thank you very much but we need this money to meet the needs of children who are dying right now so we will put the debt servicing payments into urgent social investment in health, education, drinking water, control of AIDS and other needs" (Professor Jeffrey Sachs, Director of The Earth Institute at Columbia University and Special Economic Advisor to then UN Secretary General Kofi Annan).[8]

Critics of the IMF have conducted studies as to the effects of its policy which demands currency devaluations. They pose the argument that the IMF requires these devaluations as a condition for refinancing loans, while simultaneously insisting that the loan be repaid in dollars or other First World currencies against which the underdeveloped country's currency had been devalued. This, they say, increases the respective debt by the same percentage of the currency being devalued, therefore amounting to a scheme for keeping Third World nations in perpetual indebtedness, impoverishment and neocolonial dependence.

Sino-African relations

In recent years, the People's Republic of China has built increasingly stronger ties with African nations.[9][10] China is currently Africa's third largest trading partner, after the United States and former colonial power France. As of August 2007, there were an estimated 750,000 Chinese nationals working or living for extended periods in different African countries.[11][12] China is picking up natural resourcesâoil, precious mineralsâto feed its expanding economy and new markets for its burgeoning enterprises.[13][14] In 2006, two-way trade had increased to $50 billion.[15]

Human rights advocates and opponents of the Sudanese government portray China's role in providing weapons and aircraft as a cynical attempt to obtain petroleum and natural gas just as colonial powers once supplied African chieftains with the military means to maintain control as they extracted natural resources.[16][17][18] According to China's critics, China has offered Sudan support threatening to use its veto on the U.N. Security Council to protect Khartoum from sanctions and has been able to water down every resolution on Darfur in order to protect its interests in Sudan.[19] However, China may appear to be rebuked here for doing exactly what the Western powers have always done, that is, promote their own interests by creating spheres of influence.

Other approaches to the concept of neocolonialism

Although the concept of neocolonialism was developed by Marxists and is generally employed by the political left, the term Neocolonialism is also used within other theoretical frameworks.

Cultural theory

One variant of neocolonialism theory suggests the existence of cultural colonialism, the alleged desire of wealthy nations to control other nations' values and perceptions through cultural means, such as media, language, education, and religion, purportedly ultimately for economic reasons.

One element of this is a critique of "Colonial Mentality" which writers have traced well beyond the legacy of 19th century colonial empires. These critics argue that people, once subject to colonial or imperial rule, latch onto physical and cultural differences between the foreigners and themselves, leading some to associate power and success with the foreigners' ways. This eventually leads to the foreigners' ways being regarded as the better way and being held in a higher esteem than previous indigenous ways. In much the same fashion, and with the same reasoning of better-ness, the colonized may over time equate the colonizersâ race or ethnicity itself as being responsible for their superiority. Cultural rejections of colonialism, such as the Negritude movement, or simply the embracing of seemingly authentic local culture are then seen in a post colonial world as a necessary part of the struggle against domination. By the same reasoning, importation or continuation of cultural mores or elements from former colonial powers may be regarded as a form of Neocolonialism.

Decolonization of the mind

Ngugi wa Thiongâo used the expression "decolonization of the mind." He argued that much that is written about the problems of Africa perpetuates the idea that primitive tribalism lies at their root:

The study of the African realities has for too long been seen in terms of tribes. Whatever happens in Kenya, Uganda, Malawi is because of Tribe A versus Tribe B. Whatever erupts in Zaire, Nigeria, Liberia, Zambia is because of the traditional enmity between Tribe D and Tribe C. A variation of the same stock interpretation is Moslem versus Christian or Catholic versus Protestant where a people does not easily fall into "tribes." Even literature is sometimes evaluated in terms of the "tribal" origins of the authors or the "tribal" origins and composition of the characters in a given novel or play. This misleading stock interpretation of the African realities has been popularized by the western media which likes to deflect people from seeing that imperialism is still the root cause of many problems in Africa. Unfortunately some African intellectuals have fallen victimsâa few incurably soâto that scheme and they are unable to see the divide-and-rule colonial origins of explaining any differences of intellectual outlook or any political clashes in terms of the ethnic origins of the actors â¦.[20]

The artificial creation of boundaries, together with the way in which colonial powers played different communities off against each other to justify their rule maintaining peace, rather than ancient animosities between this and that tribe causes tension, conflict and authoritarian responses. The way in which Africa and Africans are depicted in works of fiction, too, perpetuates stereotypes of dependency, primitiveness, tribalism and a copy-cat rather than creative mentality. Those who argue that continued dependency stems in part from a psychology that informs an attitude of racial, intellectual or cultural inferiority are also speaking of the need to decolonize the mind.

In postcolonialism theory

Postcolonialism is a set of theories in philosophy, film, political sciences and literature that deal with the cultural legacy of colonial rule. Postcolonialism deals with cultural identity in colonized societies, referencing neocolonialism as the background for contemporary dilemmas of developing a national identity after colonial rule: the ways in which writers articulate and celebrate that identity (often reclaiming it from and maintaining strong connections with the colonizer); the ways in which the knowledge of the colonized (subordinated) people has been generated and used to serve the colonizer's interests; and the ways in which the colonizer's literature has justified colonialism via images of the colonized as a perpetually inferior people, society and culture.

Theories of postcolonial studies include Subaltern Studies (specifically its postcolonial manifestations), Frantz Fanon's " psychopathology of colonization," and filmmakers of the Latin American Third Cinema (such as Tomás Gutiérrez Alea of Cuba or Kidlat Tahimik of the Philippines).

Critical theory

While critiques of Postcolonialism/neocolonialism theory is widely practiced in Literary theory, International Relations theory also has defined Postcolonialism as a field of study. While the lasting effects of cultural colonialism is of central interest in cultural critiques of neocolonialism, their intellectual antecedents are economic theories of neocolonialism: Marxist Dependency theory) and mainstream criticism of capitalist Neoliberalism. Critical international relations theory frequently references neocolonialism from Marxist positions as well as postpositivist positions, including postmodernist, postcolonial and feminist approaches, which differ from both realism and liberalism in their epistemological and ontological premises.

Conservation and neocolonialism

There have been other critiques that the modern conservation movement, as taken up by international organizations such as the World Wide Fund for Nature, has inadvertently set up a neocolonialist relationship with underdeveloped nations.[21]

Dependency, domination, and the world system: Reform of the UN.

Even the aid, relief and development efforts carried out both by government of the rich North in the poorer South attracts criticism for furthering the agendas of the powerful. For example, Ziauddin Sardar wrote:

"Humanitarian work," "charitable work," "development assistance," and "disaster relief" are all smokescreens for the real motives behind the NGO presence in the South, self-aggrandizement, promotion of Western values and civilization, increasing conversion to Christianity, inducing dependency, demonstrating the helplessness of those they are supposedly helping and promoting what has been aptly described as "disaster pornography."[23]

Egyptian novelists and leading feminist, Nawal El Saadawi, agrees with the argument described above that the IMF and the World Bank, induce dependency. The Policies of the IMF and World Bank increase "the flow of money and riches from North to South" so much so that "development" is "just another word for neocolonialism."[24]

She continues:

How can we speak about real development in Africa, Asia or South America without knowing the real reasons for poverty and mal development and for the growing disparity between the rich and the poor at the international and regional levels but also within each society ⦠We cannot speak about global justice without also speaking about inequality between countries, inequality between classes in each country and inequality between the sexes ⦠The word "aid" is just as deceiving. We know that money and riches flow from the South to the North, not in the opposite direction⦠this creates the false idea that we receive aid from the North. Human dignity is based on being independent and self-reliant, on producing what we eat not living on what comes from the exterior... Aid is a myth that should be demystified. Many countries in the South have started to raise the slogan, "Fair trade not aid." What the South needs in order to fight poverty is a new international economic order based on justice, on fair trade laws between countries, not "aid" and "charity." Charity and injustice are two faces of the same coin.[25]

A New World Order

The call for a new international economic order, arguably, needs to be supplemented by a new international order. As long as nation states, some argue, remain the basic unit of political organization, powerful nations will continue to shape the world according to their agendas and interests. The creation of the United Nations after World War II was intended both to end war and to enable human cooperation to improve life for all people, the "we the people" in whose name the UN Charter was written and endorsed. Some hoped that a form of world government would evolve, which might ensure global justice and the demise of war. However, the great powers of the world, without whose cooperation and support the UN could not have been formed, built privilege into the system. Without including a veto for themselves, the great powers would not have joined the new body, which, without their membership, would have been meaningless. Few have asked, as the number of nation states in the world rose from 50 mid-twentieth century to 192 at the century's end, whether forming a nation state was always in the best interests of the people who would become their citizens. Equality between states, for which Saadawi calls, is probably impossible; rich states are not equal with poor states and this disparity is likely to remain until and unless humans choose to organize their political associations differently. Some very small territories have become "states." Might they not have formed confederacies with other smaller units? Benjamin Barber has argued for a new order in which governance is devolved downwards, to smaller, more local communities.

Such governance would be participatory, possible voluntary. This would enable free and open exchange of solution and ideas between people with bond of friendship within a network of local loyalties. In the West, the nation state, says Berber, is "too identified with bureaucracy, inefficiency, and a professional political class, in whom peoples everywhere have lost confidence."[26] Barber argues that two rival, totalizing tendencies, Western commercial interests on the one side, represented by globalization understood as "McWorld" and by Muslim totalitarianism are competing for supremacy.</ref>Globalization here is understood as a synonym for Westernization, for Western domination of the international order, not as the creation of a just world in which all cultures are respected. What becomes globalized is one civilization at the expense of the rest.</ref> While jihad and McWorld pull in opposite directions, he says, the first towards the local, the second towards the global both "make war on the sovereign nation-state"[27] Devolution, Barber suggests, would allow local communities to find ways of preserving what they value in their faith and cultural traditions, "to sustain solidarity and traditions against the stateâs legalistic and pluralistic abstractions" while the "relative homogeneity of the entities whose anti-statist and anti-modern forces incline them to Jihad can potentially incline them to local participatory democracy" as well.[28] Elsewhere, the nation state is seen as a Western imposition. Barber thinks, however, that at the regional or world level what might emerge would be a con-federal association.[29] Some responsibilities would devolve upwards, such as maintaining peace in a demilitarized world. Full abolition of privilege within the world system may be over idealistic; realpolitik may require some form of permanent membership of a Security Council but without the power of veto. Commenting on the ideas of Barber and others and discussing the possibility of a world free from neo-colonialism, exploitation and injustice, Bennett wrote:[30]

Devolution would, for example, enable local communities of Muslims and others to construct their own micro-systems, to try out their ideas, to exercise self-determination, which is a basic human right. Local, self-governing communities could cooperate with others, perhaps within an historical nation state, perhaps in new forms of federal association. Barber thinks that some form of con-federalism could emerge as a framework for world governance. The European Union could serve as a model although more power would be delegated in both directions. Both foreign aid and foreign affairs would reside at international level, so that instead of a national acting in its interests the interests of all the people of the world will be considered. What we currently call "defense" would also reside at the international level but in a demilitarized world this might be renamed "dispute resolution" ⦠Instead of being a top-down system, this would be a bottom up system resting on the foundation of local civil societies. Civil societies would be participatory. Local people would decide on local issues. Paid local politicians may no longer be needed. Citizens might "log onto a civic bulletin board across national boundaries."[31]

A religious perspective

Some Christians and people of religious faith believe that God's intent for the world is a single-nation, into which the wealth, wisdom but not the weapons of the many nations will flow, based on an interpretation of Revelations 21: 26. Then the Messianic era of peace and justice promised by such passages as Isaiah 11 and 65 will finally dawn. From a neo-conservative political perspective, Francis Fukuyama has argued that what he calls the liberal society is the apex of human achievement. In and between such societies, he argues, war will diminish and eventually fade away. This represents the maturation of human consciousness. Central to Fukuyam's scenario is the concept of thymos which may be described as "an innate human sense of justice," as the "psychological seat of all the noble virtues like selflessness, idealism, morality, self-sacrifice, courage and honorability"[32] In Plato, it was linked with "a good political order."[33] Thymos enables us to firstly assign worth to ourselves, and to feel indignant when our worth is devalued then to assign "worth to other people" and to feel "anger on behalf of others."[34] As an essential feature of what he means by "liberal societies," thymos would result in the end of global injustice, inequality and violent resolution of disputes. Indeed, history as we know it, which mainly comprises the story of wars between and within states, would end; thenceforth, international relations would deal with "the solving of technological problems, environmental concerns and the satisfaction of sophisticated consumer demands."[35] This converging of religious and non-religious thinking about what type of world humans might succeed in constructing suggests that the human conscience will ultimately not tolerate the perpetuation of injustice, the continuation of violence and of inequality between people.

See also

Notes

- â United Nations General Assembly Resolutions, 1514 and 1541, UN. Retrieved August 20, 2008.

- â Kwame Nkrumah, Neo-Colonialism: The Last Stage of Imperialism (Edinburgh, UK: Thomas Nelson, ISBN 9780717801404). Retrieved August 20, 2008.

- â Wallerstein (1974), 52.

- â Kaye Whiteman, The man who ran Francafrique, National Interest. Retrieved August 20, 2008.

- â François-Xavier Verschave, La Françafrique, le plus long scandale de la République (Paris, FR: Stock, ISBN 9782234049482).

- â Mongo Beti, Main basse sur le Cameroun: autopsie d'une décolonisation (Paris, FR: Maspero, 1977, ISBN 9782707105608).

- â Ernest Mandel, Semicolonial Countries and Semi-Industrialized Dependent Countries, New International 5 (1985): 149-175.

- â Andrew England, Africa's poorest "should refuse to pay the debt," The Financial Times. Retrieved August 20, 2008.

- â Susan Puska, Military backs China's Africa adventure, Asia Times. Retrieved August 20, 2008.

- â BBC News, Mbeki warns on China-Africa ties. Retrieved August 20, 2008.

- â Howard W. French and Lydia Polgreen, 2007, Chinese flocking in numbers to a new frontier: Africa, The International Herald Tribune. Retrieved August 20, 2008.

- â World Communist Current, Chinese imperialism in Africa. Retrieved August 20, 2008.

- â Susan Hanson, China, Africa, and Oil, Washington, DC: Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved August 20, 2008.

- â Green Left Online, Is China Africa's new imperialist power?

- â Conal Walsh, Is China the new colonial power in Africa? Retrieved August 20, 2008.

- â China's Involvement in Sudan: Arms and Oil. Human Rights Watch. November 2003. Retrieved August 20, 2003.

- â Peter Goodman, China Invests Heavily In Sudan's Oil Industry, The Washington Post. Retrieved August 20, 2008

- â Reeves, Artists abetting genocide? The Boston Globe. Retrieved August 20, 2008.

- â Adam Wolfe, The Increasing Importance of African Oil, Power & Interest News Report. Retrieved August 20, 2008.

- â Ngugi wa Thiongâo, Decolonizing the Mind, The Swaraj Foundation. Retrieved August 20, 2008.

- â Modern History Sourcebook: Summary of Wallerstein on World System Theory (NY: Fordham University).

- â Rakiya Omaari and Alex de Waal, 2007, Disaster Pornography from Somalia, Malibu, CA: Center for Media Literacy. Retrieved August 20, 2008.

- â Sardar (1998), 78.

- â SaÊ»dÄwÄ« (1997), 12.

- â SaÊ»dÄwÄ« (1997), 12-13.

- â Barber (1996), 276.

- â Barber (1996), 6.

- â Barber (1996), 231.

- â Barber, 1992, Jihad vs. McWorld, Atlantic Monthly. Retrieved August 20, 2008.

- â Bennett (2008), 231.

- â Barber (1996), 287.

- â Fukuyama (1992), 171.

- â Fukuyama (1992), 169.

- â Fukuyama (1992), 171.

- â Fukuyama (1992), 18.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Agyeman, Opoko. 1992 Nkrumah's Ghana and East Africa: Pan-Africanism and African Interstate Relations. Rutherford, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 9780838634561.

- Ankerl, Guy. 2000. Global Communication Without Universal Civilization. INU societal research. Geneva, CH: INU Press. ISBN 9782881550041.

- Ashcroft, Bill, Gareth Griffiths, and Helen Tiffin. 1995. The Post-Colonial Studies Reader. London, UK: Routledge. ISBN 9780415096218.

- Barber, Benjamin R. 1996. Jihad vs. McWorld. New York, NY: Ballantine Books. ISBN 9780345383044.

- Barongo. Yolamu, R. 1980. Neocolonialism and African Politics: A Survey of the Impact of Neocolonialism on African Political Behavior. New York, NY: Vantage Press. ISBN 9780533044382.

- Bennett, Clinton. 2008. In Search of Solutions: The Problem of Religion and Conflict. Religion and violence. London, UK: Equinox Pub. ISBN 9781845532390.

- Beti, Mongo. 1972. 2003. Main basse sur le Cameroun. Autopsie d'une décolonisation. Paris, FR: Maspero. ISBN 9782707105608.

- Bhavnani, Kum-Kum, John Foran and Priya A. Kurian. 2003. Feminist Futures: Re-Imagining Women, Culture and Development. New York, NY: Zed Books. ISBN 9781842770283.

- Birmingham, David. 1995. The Decolonization of Africa. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press. ISBN 9780821411537.

- Constantino, Renato. 1978. Neocolonial Identity and Counter-Consciousness: Essays on Cultural Decolonization. White Plains, NY: M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 9780873321334.

- Conway, George A. W. 1996. A Responsible Complicity: Neocolonial Power-Knowledge and the Work of Foucault, Said, Spivak. Ottawa, CA: University of Western Ontario Press. ISBN 9780612210394.

- Emberley, Julia V. 1993. Thresholds of Difference: Feminist Critique, Native Women's Writings, Postcolonial Theory. Toronto, CA: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 9780802028501.

- Ermolov, Nikolai Aleksandrovich. 1966. Trojan Horse of Neocolonialism: U.S. Policy of Training Specialists for Developing Countries. Moscow, RU: Progress Publishers.

- Frank, Andre Gunder. 1975. On Capitalist Underdevelopment. Bombay, IN: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195604757.

- Fukuyama, Francis. 1992. The End of History and the Last Man. New York, NY: Free Press. ISBN 9780029109755.

- Gladwin, Thomas and Ahmad Saidin. 1980. Slaves of the White Myth: The Psychology of Neocolonialism. Atlantic Highlands, NJ: Humanities Press. ISBN 9780391019362.

- Gordon, Lewis. 1997. Her Majestyâs Other Children: Sketches of Racism from a Neocolonial Age. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9780585201726.

- Hoogvelt, Ankie M. M. 2001. Globalization and the Postcolonial World: The new Political Economy of Development. Baltimore. MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 9780801856440.

- Hooker, M.B. 1975. Legal Pluralism; an Introduction to Colonial and Neo-Colonial Laws. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press. ISBN 9780198253297.

- Kramer, E.M. (ed.). 2003. The Emerging Monoculture: Assimilation and the "Model Minority." Westport, CT: Praeger. ISBN 9780275973124.

- Lundestad, Geir (ed.). 1994. The Fall of Great Powers: Peace, Stability, and Legitimacy. Oslo, NO: Scandinavian University Press. ISBN 9788200219224.

- Parry, Benita, and Laura Chrisman. 2000. Postcolonial Theory and Criticism. Cambridge, UK: D.S. Brewer. ISBN 9780859915540.

- SaÊ»dÄwÄ«, NawÄl El. 1997. The Nawal El Saadawi Reader. London, UK: Zed Books. ISBN 9781856495134.

- Sardar, Ziauddin. 1998. Postmodernism and the Other the New Imperialism of Western Culture. London, UK: Pluto Press. ISBN 9780585337944.

- Sartre, Jean-Paul. 2001. Colonialism and Neocolonialism. London, UK: Routledge. ISBN 9780415191456.

- Seborer, Stuart J. 1974. U.S. Neocolonialism in Africa. New York, NY: International Publishers. ISBN 9780717803927.

- Simon, D. 1992. Cities, Capital and Development: African Cities in the World Economy. New York, NY: Halstead. ISBN 9781852932749.

- Singer (ed.). 1977. Traditional Healing, new Science or new Colonialism. Owerri, NY: Conch Magazine. ISBN 9780914970361.

- Suret-Canale, Jean. 1983. Essays on African History: From the Slave Trade to Neocolonialism. Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press. ISBN 9780865430921.

- Thiongʼo, Ngũgĩ wa. 1983. Barrel of a Pen: Resistance to Repression in Neo-Colonial Kenya. Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, of the Africa Research & Publications Project. ISBN 9780865430013.

- Thiongʼo, Ngũgĩ wa. 1986. Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature. London, UK: J. Currey. ISBN 9780435080167.

- Thiongʼo, Ngũgĩ wa, and Charles Cantalupo. 1995. The World of Ngūgī wa Thiong'o. Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press. ISBN 9780865434585.

- Treto, Carlos Alzugaray. 1995. El ocaso de un régimen neocolonial: Estados Unidos y la dictadura de Batista durante 1958. (The twilight of a neocolonial regime: The United States and Batista during 1958). In Temas: Cultura, IdeologÃa y Sociedad. 16-17:29-41.

- Wallerstein, Immanuel. 1974. The Modern World System: Capitalist Agriculture and the Origins of the European World Economy in the Sixteenth Century. New York, NY: Academic Press. ISBN 9780127859217.

- Werbner, Richard and T.O. Ranger. 1996. Postcolonial Identities in Africa. Atlantic Highland, NJ: Zed Books. ISBN 9781856494151.

External links

All links retrieved November 11, 2022.

- Mbeki warns on China-Africa ties.

- Neo-Colonialism: The Last Stage of Imperialism, by Kwame Nkrumah (former Prime Minister and President of Ghana), originally published 1965.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.